SOLAR HOT WATER SYSTEMS

SATISFYING DOMESTIC HOT WATER NEDS WITH SOLAR ENERGY

Solar energy is a gift from the sun, but one that’s vastly underutilized by human society. As natural gas supplies dwindle and prices skyrocket, however, more and more people will turn to the sun to meet their needs for energy. We’ll use the sun’s energy to heat our homes (Chapter 5) and to produce electricity to power homes, cars, schools, hospitals, businesses, and factories (Chapter 8). Many people will also start using the sun’s massive outpouring of energy to heat water for showers, baths, washing clothes, and dish washing. This chapter explores this application, known as domestic solar hot water (DSHW). Besides ensuring our comfort and promoting personal hygiene, hot water constitutes a huge portion of our annual fuel bill — about 13 percent of the average annual household fuel bill in the United States, according to the US Department of Energy. As natural gas production declines and prices climb, the cost of supplying domestic hot water could rise meteorically. Those who retrofit their homes for solar hot water could save a sizeable amount of money.

However, before deciding to install a solar hot water system, you should first understand how conventional hot water systems work, because solar hot water systems are typically integrated with them.

CONVENTIONAL HOT WATER SYSTEMS

In most homes in North America, hot water is provided by a conventional gas, electric, or oil storage water heater — widely (and incorrectly) referred to as “hot water heaters.” (They don’t heat hot water!) The storage water heater consists of a freestanding water tank that holds 40 to 80 gallons of hot water (Figure 3-1). The tank itself consists of a steel tank lined internally by a thin layer of glass (to prevent the steel tank from rusting). The internal steel tank is encased in a steel envelope with a layer of insulation in between them to hold heat in.

In electric storage water heaters, water is heated by two electric resistors, known as heating elements. The heating elements — one near the top and one near the bottom of the tank — generate heat when electricity flows through them, much like the electric heating elements of an electric stove. The heat produced by the resistors is transferred to the water in the tank. Each element in an electric water heater has its own thermostat. The lower element, or standby element, located at the bottom of the tank, maintains the minimum thermostat setting; the upper element, the demand element, provides hot water recovery when demand heightens — that is, it heats water very quickly when the demand for hot water increases.

Fig. 3-1: Water heaters like this one on right are popular in North America. They store 40 to 80 gallons of hot water, ready for use any time of the day or night. Although they work well, they’re not as efficient as other systems. Standby losses account for about 20 percent of the energy consumed by these units.

Gas-powered storage water heaters have a single source of heat, a burner at the bottom of the water tank. The burner is connected to a thermostat and ignites when the temperature of the water inside the tank drops below a predetermined set point. When this occurs, the temperature sensor sends a signal to a valve that regulates the flow of natural gas or propane into the burner. When the valve opens, gas flows into the burner and is ignited, most often by a small pilot light that runs 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Oil-fired water heaters operate similarly; however, they contain a power burner that mixes oil and air to create a mist that is then ignited by an electric spark.

Because the combustion of natural gas, propane, and oil produce carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide, which are potentially poisonous to people and pets, gas-powered water heaters must be vented. Venting is accomplished by a flue pipe that directs hot combustion gases and pollutants through the ceiling. In most gas-fired water heaters, combustion air that feeds the burner comes from room air. For a discussion of newer, safer, and more efficient power-vented water heaters, see the accompanying sidebar, “Power Venting: Induced Draft Water Heaters.”

Conventional storage water heaters maintain a large quantity of hot water day in and day out. This water can be used at any time. It’s there at our command. Just open a hot water faucet or turn on an appliance like a clothes washer, and you’ve got hot water in 10 to 30 seconds, depending on the distance between the faucet or appliance and the water heater.

Hot water drained from the tank is replaced by cold water from a cold water line. As it enters the tank, the cold water cools the water in the storage tank. When the temperature of the water in the tank drops below the desired setting, the gas burner ignites. Once the water reaches the desired setting, the flame turns off.

Power Venting: Induced Draft Water Heaters

Standard water heaters are popular in North America, but they are not as efficient or as safe as they could be. To address this, some companies sell power-vented water heaters, typically referred to as induced draft models. An induced draft water heater consists of a large storage tank and a burner, just like a conventional gas-powered storage water heater. However, that’s where similarities end. This new and safer water heater also includes a fan. It draws outside air into the combustion chamber and forces combustion gases out through a vent. This is important for two reasons: Bringing outside air in helps prevent leakage through cracks in the building envelope that reduces the overall energy efficiency of a home. (Air must enter a home to replace the air that exits with the combustion gases through the flue.) Power venting also actively expels combustion gases and the pollutants they contain. This ensures that pollutants produced by the combustion of natural gas or propane are vented to the outside and can’t enter the room air, causing health problems. Spillage is also prevented by a closed combustion chamber. It contains the fire and the combustion gases, unlike a standard water heater, making it impossible for them to escape into our homes. Power-vented water heaters are not only safer, they’re more efficient — usually at least 10 percent more efficient than standard gas-fired storage water heaters. In fact, they’re so much more efficient than standard storage water heaters that they can be vented with plastic flue pipes rather than the metal flue pipes of conventional water heaters. (The induced draft water heater removes much more heat from the combustion of natural gas, meaning the combustion gases are cooler.)

While safer and more efficient, these models do cost more, and they use electricity to run the fan. Your gas bills will go down, but your electric bill will go up a tiny bit. It’s not a big deal, however. The increase will hardly be noticeable.

Pros and Cons of Storage Water Heaters

Conventional storage water heaters are widely available in North America, fairly inexpensive, and are about 80 percent efficient. However, they do have some drawbacks. For one, they generally don’t last very long. You can count on replacing your water heater every 10 to 15 years, unless you take steps like those outlined in the accompanying sidebar “Water Heater Revival.”

Water Heater Revival

Storage water heaters can be made to last much longer and operate more efficiently by draining sediment from the bottom of the tanks every year. Simply open the faucet at the bottom of the tank and drain off a couple of gallons of water containing sediment. You can also extend their working life by replacing the anode in the tank. The anode is a long, slender metal rod that’s usually attached to the cold water inlet pipe of the water tank at the top of the tank. It may be attached separately, and is usually well labeled.

The anode rod extends down into the tank and prevents corrosion of the steel casing (for reasons beyond the scope of this book). Periodic replacement can double the working life of a water tank, saving you lots of money. For details on how to replace the anode, I refer you to Chuck Marken’s article in issue 106 of Home Power magazine, “New Life for Your Old Water Heater” or my book, Green Home Improvement, Project 33.

Another problem with storage water heaters is that they use natural gas and propane, two fuels slipping toward extinction. Even electric water heaters have some problems. For one, they rely on an expensive source of energy: electricity. (Electricity is the most expensive means of heating water, bar none!) Perhaps the most significant problem with storage water heaters is that they maintain a large quantity of hot water 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. In between periods of demand, heat leaks out of tanks and the pipes that attach to the top. This is called standby loss. Standby heat loss must be replaced. One fifth of the fuel consumed by a conventional storage water heater is used to offset the standby losses.

Many, myself included, believe this system wastes too much energy. It’s a little like keeping your car running in the garage 24 hours a day just in case you wake up in the middle of the night and want to take it for a spin! A far better alternative is the tankless water heater.

TANKLESS WATER HEATERS

Travel through Europe and other parts of the world, like Japan, where energy is expensive and efficiency is a cultural norm, and you won’t find storage water heaters like the ones in North American homes. In such regions, the tankless water heater is the technology of choice (Figure 3-2a). Why? Because tankless water heaters outperform their conventional counterparts easily by 20 percent or more. Like storage water heaters, tankless water heaters provide hot water on demand, but they do so without storing huge quantities of hot water. In fact, as their name suggests, they have no storage capacity at all.

Anatomy of a Tankless Water Heater

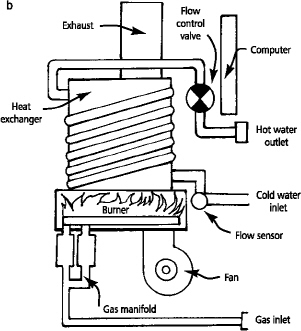

Tankless water heaters for household use are attractive, compact units that mount on the wall in a central location or near the main hot water demand centers (Figure 3-2a). The heart and soul of all tankless water heaters is a device called a heat exchanger — a combustion chamber in which cold water is quickly brought up to temperature (Figure 3-2b). The heat exchanger transfers heat from the burner to the water, heating it instantaneously. A flue pipe vents unburned gases and pollutants like carbon monoxide out of the house.

Here’s how a tankless water heater works: when hot water is required — for example, when someone turns on a hot water faucet — a water flow sensor in the water heater sends a signal to a central control module. This tiny computer, in turn, sends signals to an electronically controlled gas valve in the gas manifold. The valve opens and allows natural gas or propane to flow into the combustion chamber of the heat exchanger. The gas is ignited by a pilot light or by a spark from an electronic ignition device. Cold water flowing through the pipe in the heat exchanger is immediately brought up to the desired temperature. As soon as the hot water faucet is turned off, the water flow through the water heater ceases and the flame goes out. The result is that you heat only the water you need.

Fig. 3-2: (a) Tankless water heaters like this one heat water instantly (there’s no need to store hot water for intermittent uses) and thus reduce the amount of energy required to supply a family with hot water by about 20 percent. These units are typically mounted on walls in a central location in the house. (b) Cutaway of a tankless water heater (Courtesy: Home Power Magazine).

Under-the-Sink Water Heaters

Many tankless water heaters in use in Europe fit under the sinks of homes and apartments. They heat water for one sink only and are typically powered by electricity. The household-sized units described in this chapter are centrally located so they can service all hot water needs in a home. They are often powered by natural gas or propane, both of which are much more efficient fuel options than electricity.

Pros and Cons of Tankless Water Heaters

Tankless water heaters cost more than their conventional counterparts and are a bit more challenging to install. (This isn’t a job for most do-it-yourselfers.) However, they do provide significant advantages over storage water heaters. As just noted, they heat only the water needed at any one moment. As a result, they are usually at least 20 percent more efficient than standard water heaters. That means they provide the same amount of hot water as a storage water tank, but use 20 percent less fuel. Utility bills will be 20 percent lower, too.

Because there’s no standby loss, they also produce less waste heat. In the summer, that means less heat is generated in your home, which lowers cooling bills, the topic of Chapter 7. Another huge advantage of tankless water heaters is that they outlast conventional water heaters. They’re typically designed to last as long as a conventional furnace or boiler — twenty years or more. Moreover, tankless water heaters are easy to repair. If a part goes bad, it can be replaced. When something goes wrong, you don’t have to throw the unit out and replace it with a brand new water heater, as you do with conventional storage water heaters.

With this background in mind, let’s turn our attention to solar hot water systems and how they are integrated with conventional or tankless water heaters. (If you want to learn more about tankless water heaters, I suggest you read Jennifer Weaver’s piece on them in Home Power, Issue 105 or my book, Green Home Improvement, Project 34.)

WHAT IS A SOLAR HOT WATER SYSTEM?

Domestic solar hot water systems require solar collectors, which are typically mounted on the roofs of homes or businesses. The solar collectors capture solar energy to heat water. Most domestic solar hot water systems are designed to provide 40 to 80 percent of a household’s annual hot water needs, although 100 percent is possible. (This requires using the most efficient solar panels and is typically achieved in the sunniest locations, like southern California, Arizona, and Florida.)

Domestic solar hot water systems are usually integrated with conventional storage or tankless water heaters. (Be sure to purchase a tankless water heater that’s designed to operate in conjunction with a solar hot water system.) As you shall soon see, when operating in conjunction with a solar hot water system, conventional storage or tankless water heaters typically become secondary heat sources. That is, they back up the solar hot water system.

Although this chapter deals with systems for domestic hot water, these systems can also be designed to provide space heat for homes. Solar hot water systems can also be designed to heat greenhouses and swimming pools. They can even provide hot water for hot tubs, saving homeowners tons of money and dramatically reducing the environmental impact of using conventional heat sources. I’ll describe solar hot water systems for space heating in Chapter 5. (See Bob Owens’s piece on solar hot water systems for hot tubs listed in the Resource Guide.)

But that’s not all. Solar hot water systems are also installed for what may seem like a frivolous need — melting snow on driveways. In the upscale ski town of Aspen, Colorado, for example, many wealthy homeowners install solar hot water systems to de-ice their driveways. They’re required by law to install some kind of renewable energy system to partly make up for the large homes they build, and these systems sastisfy that requirement.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF SOLAR HOT WATER

Solar hot water is not a new technology by any stretch of the imagination. In fact, solar systems were quite popular in the early 1900s in the United States, particularly in California and Florida. An estimated eight million systems were installed on the rooftops of homes in these areas in the early 1900s.

But along came cheap natural gas, and the solar hot water industry took a nose dive. It wasn’t until the oil embargoes of the 1970s that the solar industry got back on its feet again. To decrease our nation’s dependence on foreign energy sources, in part by encouraging renewable energy, the federal government and many states offered generous financial incentives — tax credits and tax deductions — for homeowners who installed solar hot water systems. In my home state of Colorado, the combined federal and state incentives covered 60 percent of the cost of a new system.

The domestic solar hot water (DSHW) industry boomed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but during the Reagan Administration the incentives came to a screeching halt. Neither Congress nor the president was willing to extend them. President Reagan even took down the solar hot water collectors that his predecessor, Jimmy Carter, had installed. And so ended the second era of solar hot water.

Solar Driveway

In Aspen, Colorado, and other areas, solar hot water systems are often installed to keep driveways free of snow and ice. In these systems, pipes are installed beneath the driveway before the pavement is laid down. These pipes circulate a solar-heated fluid (a type of antifreeze) beneath the driveway. Even on cloudy days, the panels often produce enough heat to melt snow and ice, as the fluid circulating beneath the driveway doesn’t have to be as hot as water in our homes. It has to be just hot enough to melt snow. This application may seem like a luxury to most of us, and it is, but it beats the alternative: using a gas-fired boiler or electrical wire to achieve the same result. And it does eliminate the need to plow driveways, an activity that uses a lot of energy!

As Greg Pahl writes in his book, Natural Home Heating, “The fall of the industry was as sudden — and spectacular — as its rise.” The second coming of solar hot water was not a complete bust, however. Its meteoric rise introduced many to a sensible and economical alternative to electricity, propane, oil, and sometimes even the cheapest fuel, natural gas. Even more importantly, it resulted in the installation of numerous systems, many of which are still operating today.

The rise and fall of the solar hot water industry in the late 1970s and early 1980s did create some lasting problems. Generous tax incentives created an almost overnight industry. In their rush to deliver their products to market and tap into the incentives, some companies rushed products to market before they were fully tested. Moreover, some vendors and installers engaged in unscrupulous activities. Some overstated the economic benefits and many engaged in price gouging. I fell victim to price gouging myself. I bought a system from a company (no longer in business), paying a premium price for the equipment and installation — a whopping $6,000. Like other customers, I was willing to pay what seemed like an outlandish price. Who cared what the sticker prices was? Federal and state incentives knocked the price back down to about $2,400, including installation.

Unfortunately, when the tax incentives withered away, so did most of the companies. Many homeowners, myself included, were abandoned. When systems needed repair, we had no one to turn to. The service personnel were gone, and so were the parts we needed. Many systems fell into disrepair and were removed from roofs. You may even be able to buy some solar hot water collectors removed from roofs during this time. I have two of them myself that I’m going to install at The Evergreen Institute.

Since then, the solar hot water industry has struggled to gain a foothold. But after years of struggle, solar hot water systems are gaining in popularity thanks in part to high fuel prices, and enlightened public policy at the state and federal level. Homeowners and business owners can receive a 30 percent federal tax credit for solar hot water systems. Some states and utilities offer rebates or incentives as well. To learn about rebates in your state, visit dsireusa.org and click on your state on the US map. Even without financial incentives, DSHW systems often make good sense, as you shall soon see.

Despite the resurgence in solar hot water, the solar industry still hasn’t completely overcome the bad image lingering in the minds of many people. Unfortunately, this technology is still viewed by some as unreliable. “Happily, the industry has matured [and] the technology has improved,” notes Pahl. Today’s companies produce an excellent product. Making things better for homeowners, there are now performance standards for most of the components of active solar heating systems, which makes comparing different products much easier.

I believe that this time solar hot water is here to stay. Incentives offered at the federal and state levels could boost the industry dramatically, but they may not be needed. Market forces may drive the switch to solar hot water, creating a lasting energy source throughout the 21st century and beyond.

My recommendation to those thinking of installing a system is to go with established companies — installers and manufacturers who have been around for five to ten years. “Before you decide to buy an active solar heating system,” notes Pahl, “be sure to check local zoning ordinances, land covenants, and any other possible local restrictions” that might apply to you. “Homeowner association rules, in particular, can be a real headache when it comes to solar collectors.” Although such restrictions are not widespread, they can be insurmountable. If you do run into local restrictions, you may want to invest some time, energy, and money to reverse them. As Pahl notes, “Most of these restrictions are absurd and deserve to be changed, so it’s probably worth the effort if you are committed to solar heating.” We need solar pioneers who will help pave the way for others.

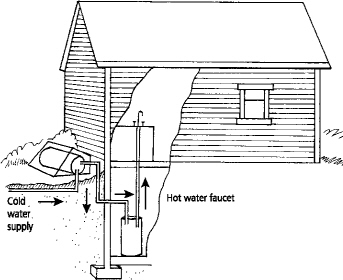

SOLAR HOT WATER SYSTEMS

Domestic solar hot water systems consist of several basic components. The two most prominent are the solar panels (more appropriately referred to as “solar collectors”) and the water storage tank. The solar collectors are usually located on the roof or on the ground next to a house or business. In both locations, they need to be positioned so they receive full sunlight year round (Figure 3-3). The water storage tank is typically located next to the conventional water heater, often in the basement of a home. Copper pipes connect the collectors with the storage tank, and various pumps, sensors, valves, and controls ensure that the system works automatically. Because many DSHW systems utilize pumps, they are classified as active systems. (As you shall soon see, though, there are a few DSHW systems that require no pumps at all.)

Fig. 3-3: The most prominent part of a solar hot water system is the solar collector. Collectors are typically mounted on the roofs of houses or alongside homes to ensure year-round exposure to the sun from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. each day. Heat energy gathered from sunlight is stored in a water tank, usually located in the basement, for use when needed. This model by Sol-Reliant uses a PV module to provide electricity to pump. No additional wiring is necessary.

Solar hot water systems work in all climates, from the sunniest areas (the sunbelt) to the dreariest of all climate zones (the so-called Gloom Belts). The type of system you install depends on the climate, as you shall soon see. With this overview in mind, let’s take a look at your options, starting with the simplest of all systems.

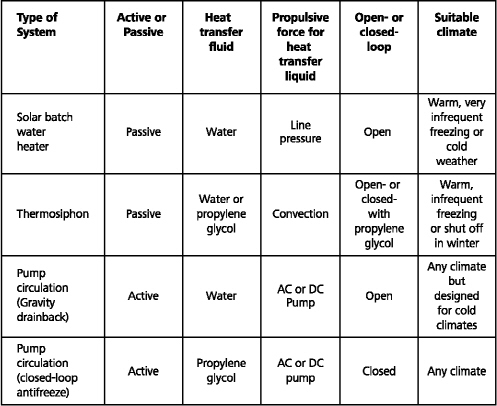

Table 3-1 provides a summary of the types of systems. You’ll note that the table lists whether a system is active or passive, the type of heat transfer fluid that circulates through the solar collectors, what moves this fluid, whether the system is open or closed (explained shortly), and finally, the suitable climate.

Domestic solar hot water systems fit into one of two broad categories: direct or indirect. Open systems (a.k.a. direct systems) heat water that you use. In other words, water circulates through the collectors, is heated and then used inside a home or business. Closed-loop systems (a.k.a. indirect systems) heat a fluid that then heats the water.

Table 3-1

Solar Hot Water Systems

Solar Batch Hot Water Systems

The simplest of all the solar hot water systems on the market is the solar batch hot water system. Solar batch water heaters are popular in many tropical countries, such as Mexico. In such locations, solar batch water heaters consist of a single water tank mounted on the roofs of homes and businesses. The tanks are typically painted black to increase the absorption of solar energy.

Solar batch water tanks absorb sunlight all day long, which heats the water inside the tank. When hot water is required, it flows directly out of the top of the tank into the hot water supply line that feeds various hot water faucets inside the building. Cold water enters the bottom of the tank to replenish hot water drawn out of the tank with each use. Because the water used in the house is heated in the tank, the solar batch hot water system is considered a direct or open-loop solar hot water system.

Solar batch water heaters like these are simple, economical, and reliable. However, they do have some shortcomings. One of those shortcomings is that the tanks are not insulated. As a result, they tend to lose a lot of heat at night. The hottest water is, therefore, typically available only in the afternoons and the early evenings.

But don’t close the book on solar batch water heaters just yet. More efficient — and more attractive — models are available. One type, shown in Figure 3-4, consists of a large black storage tank inside a glass-covered, insulated collector. Sometimes referred to as integrated collector and storage (ICS) water heaters because the collector and storage tank are one unit, these models are mounted on roofs, so long as the roof can support the additional weight; they can also be installed on the ground, alongside buildings.

Fig. 3-4: The solar batch water heater is one of the simplest and most cost-effective solar hot water systems available on the market today. Unfortunately, it can only be used in warmer climates, where freezing rarely, if ever, occurs.

For best results, batch heaters must face true south, not magnetic south. (True south corresponds to the lines of longitude and is not often the same as magnetic south, which is determined by magnetic fields. Magnetic fields don’t always run true north and south.) Like all other solar collection devices you’ll encounter in this and other chapters, solar batch water heaters need to be in a sunny location free from shade, day in and day out, 12 months a year, for optimal performance.

As noted above, solar batch water heaters heat water during the day. In the United States and other more developed countries, however, solar batch water heaters are typically plumbed into a home’s water heater. Therefore, they provide preheated water to a conventional water heater.

To understand how a solar batch water heater operates in such an installation, let’s trace the flow of water, beginning in the bathroom shower, say on a hot summer day (Figure 3-5). When a hot water faucet is turned on in the shower, hot water is drawn from the conventional water heater.

Replacement water flows directly into the storage water heater from the solar batch water heater. However, because solar batch water heaters often produce extremely hot water, over 160°F (71°C), installers must be sure to provide a means of reducing water temperature to prevent parboiling residents. This is achieved by placing a mixing or tempering valve between the hot water line leaving the water heater and the cold water line. This “smart valve” senses the temperature of the water leaving the tank. If it is too hot, the valve opens, permitting cold water to mix with the scalding hot water, achieving the desired temperature for showers and other domestic uses.

What happens on cooler, cloudy days when the temperature of the water in the batch heater only reaches 90°F (32°C), well below a comfortable setting for a shower? Will you end up taking a cold shower on those days? No. In such instances, water temperature is maintained by the conventional water heater. When you turn on the shower, hot water flows out of the storage water heater, whose temperature is controlled thermostatically. Replacement water comes from the solar batch collector. It is warmer than line water by 40 degrees, give or take a little. This preheated water flows into the conventional water heater where its temperature is boosted to the desired setting (usually around 120°F [49°C]). On such days, then, the batch heater preheats the water that flows into the storage water heater tank or the tankless water heater.

Fig. 3-5: In a solar batch hot water system, hot water for use inside the house is typically drawn from the storage water heater tank. The tank is replenished by water from the solar batch collector. Its tank is replenished by line water.

Turn Off Your Water Heater Entirely!

During really hot sunny weather, homeowners with solar batch water heaters — and other types of solar hot water systems — often turn off their conventional water heaters. During such periods, the batch heater provides 100 percent of their needs. This is accomplished by installing a bypass valve that allows water from the batch heater to be diverted past the water heater. When a hot water faucet is turned on, water flows directly from the batch heater into the hot water line. A special mixing or tempering valve needs to be in the line, however, to prevent scalding.

The value of this arrangement is simple: On sunny days, the batch heater provides really hot water so that your storage water heater or tankless water heater doesn’t have to do a thing. It just doles out hot water as needed. On cloudy days, though, the batch heater makes the water heater’s job easier by providing preheated water.

Fig. 3-6: This modern progressive tube solar batch water heater (a) is much less obtrusive than older solar batch water heaters. It mounts on the roof (b).

The water heater will operate, but it won’t need to run very long to bring water up to a suitable temperature. As a result, a solar batch water heater can save energy and reduce utility bills even when not operating full tilt.

If the solar batch heater just described is too bulky for you, don’t despair, there’s a sleeker model that might fit the bill. It is known as a progressive tube solar water heater, and is shown in Figure 3-6b. This sleek four-foot by eight-foot collector mounts on the roof of a home and consists of long four-inch copper water pipes aligned horizontally (Figure 3-6a). The copper pipes are coated on the outside with a selective surface (sometimes called black chrome). Selective surface materials absorb sunlight (visible light) more efficiently than conventional black surfaces and convert it into heat. The heat is then transferred to the water inside the pipes. (Selective surfaces also reduce heat radiation back through the glass, and thus boost the efficiency of the water heater.)

The progressive tube solar water heater is glass-covered, like a batch heater, and highly insulated. The insulated metal box attaches to the roof via metal roof mounts and can withstand winds up to 180 miles per hour, according to the manufacturer.

As shown in Figure 3-6a, hot water is drawn off the top of the solar batch water heater here and is replaced by cold water that enters at the bottom of the collector. As water flows through the collector, it is heated by the sun.

Like other batch water heaters, the progressive tube solar water heater serves as a preheat tank on cooler, cloudy days, but can meet 100 percent of a family’s hot water needs on warm, sunny days. Like other batch water heaters, this one requires no pumps, sensors, controls, or other moving or electronic parts. The progressive tube solar water heater comes in 30-, 40-, and 50- gallon sizes. When full, these units weigh upwards of 600 pounds — so be sure your roof can handle the load!

Pros and Cons of Batch Heaters

Batch heaters have no moving parts and are therefore the most reliable solar water heaters on the market today. They are available through solar suppliers such as Gaiam Real Goods, but can also be manufactured at home using common building materials — an old water heater tank, wood, glass, and black paint.

Batch heaters are inexpensive and relatively easy to install, although basic plumbing skills are required. Batch heaters don’t require a pump, either, as noted above. Nor do they require temperature sensors. Because they’re free of electronic controls, sensors, and pumps, they also require no electricity to run. They operate on line pressure — the water pressure in the pipes of your home.

Solar batch water heaters tied to domestic hot water systems provide year-round water heating in areas where freezing temperatures rarely occur. However, they’ll even work in areas that experience an occasional freeze, such as northern Florida. That’s because the large mass of heated water stored in the tanks resists freezing, making batch heaters immune to an occasional freeze — so long as it doesn’t last too long. (In such locations, though, the supply and return lines may be susceptible to freezing, so it is wise to insulate them well and to keep pipe runs short.)

Solar batch water heaters are not without problems, however. Most notably, they’re of no value in colder climates — places where freezing temperatures are a more common occurrence. You can pretty much forget about installing a solar batch water heater for year-round hot water if you live in Minnesota, North Dakota, Maine, or even Kansas — or any other area with long, cold winters. If you live in a climate that freezes with any regularity, though, you may want to install a batch heater anyway but only use it during the spring, summer, and fall. You’ll need to drain the system when freezing temperatures arrive. If you want year-round solar hot water, though, you should consider one of the other systems you’ll learn about shortly.

Another issue to be aware of is that while batch heaters are cheap, shipping costs can be significant. These units are pretty heavy! Don’t forget to add this expense when calculating the system cost. When filled with water, batch heaters are even heavier, so roofs need to be capable of supporting the additional weight, as noted earlier. In older homes, installation of a solar batch heater may require additional supportive roof framing. When contemplating this option, check your roof framing to be sure that it is up to the task. It is best to consult a structural engineer or contact your local building department to get their advice before you order a solar batch water heater.

Another potential disadvantage for many families is that solar batch water heaters may require a slight change in lifestyle. To get the most from a batch heater, you will need to synchronize your family’s hot water use patterns with the batch heater’s hot water production. Many homeowners who’ve installed these systems, for example, make an initial draw of hot water early in the afternoon, for example, to run a dishwasher or clothes washer because the water inside the tank is quite hot at this time.

After drawing off hot water, water temperature in the batch heater falls. If the sun is still shining, however, the batch heater will reheat, so there’s plenty of hot water by the end of the day. Showers can be taken in the early evening to utilize the hot water remaining in the tank. You can still take a shower in the morning, but remember that batch heaters cool down at night. Replacement water flowing into the storage water heater from the batch heater will be a tad cooler than it was at the end of the day. But don’t worry. You won’t be showering in cold water at night; shower water comes from your water heater, which maintains a comfortable temperature for your shower. The water heater will just have to work a little harder, as it is being fed slightly cooler water. To combat nighttime cooling, you can cover the glass covering of the batch heater with a thick layer of insulation each night. This will help maintain high temperature, but will involve a bit of work on your part.

Clearly, to make the most of a batch heater, homeowners need to carefully manage water use. Such systems can work well for retirees or those of us who work at home. We can reschedule clothes washing and showers more easily than those who dart off to work each day. Another downside of solar batch water heaters is that they’re designed for smaller households of two to four people. But like so many things, there are ways around this limitation. If you need more hot water, you can always install two (or more) batch heaters side-by-side (in series) to boost hot water production.

Separate Collection and Storage Systems

As you have just seen, batch solar hot water systems combine storage and collection in one unit. Because of this, the water storage tank is exposed to the cooler outdoor air at night or on cold days, with obvious disadvantages. For a system that performs year-round, solar designers have separated the collection and storage functions. They have placed the collection unit, the solar panels, on the outside of the house, usually on the roof, and sequestered the storage tank inside the building, where it is much warmer. That way, hot water generated during the day isn’t lost to the cold evening air. As a result, these systems can operate efficiently even in the coldest weather.

Separate collection and storage systems make up the bulk of the solar hot water systems in use today. The two most common types of collectors in use today in these systems are the flat plate collector and the evacuated tube collector. Let’s take a look at each type of collector, before we explore the different types of DSHW systems.

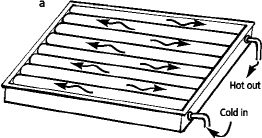

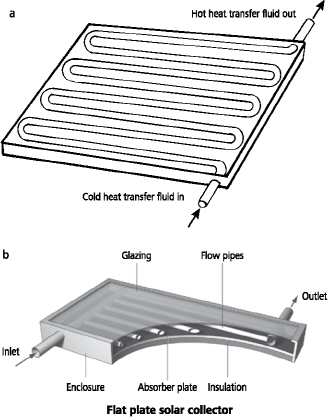

Flat Plate Collectors

The flat plate collector consists of a glass-covered insulated box. Inside are copper pipes attached to a flat absorber plate, all painted black to optimize solar gain. (The black paint is usually a selective surface material described in the accompanying sidebar.) The pipes in a flat plate collector can be arranged in series, which means that the water flows in one end and out the other end, as shown in Figure 3-7a or parallel as shown in Figure 3-7b.

Fig. 3-7a and b: Flat plate collectors are the most popular models. (a) Copper pipes in this collector form a continuous run. (b) In this more common design, water flows into the collector at the bottom, then runs upward through parallel copper tubes where it is heated.

Sunlight entering a flat plate collector is absorbed by the dark-colored absorber plate where it is converted to heat. A heat transfer fluid flowing through the pipes absorbs much of the heat and transports it out of the collector. This liquid delivers the heat to the well-insulated solar water tank. It stores hot water that is fed into a storage water heater or tankless water heater.

Flat plate collectors are the most commonly used collector on the market today; they are useful for lower temperature applications, that is, applications that require water temperatures under 140°F (60°C), for example, domestic hot water. They’re also useful in two space-heating applications: radiant floor and forced-air heating systems (discussed in Chapter 5). But they often don’t produce high enough temperatures to work with baseboard hot water systems but can work in such systems with careful planning.

Selective Surfaces

Researchers have discovered unique ways to capture solar energy and convert it to heat. One of them is a special coating applied to solar hot water panels, called selective surfaces. Selective surfaces have been around since the 1950s. They are coatings that are much more efficient at absorbing sunlight (visible light) than a coating of black paint. (They have a “higher absorbance.”) Not only do they absorb more light and convert it to heat, they also lose less heat than a black painted material. That is, they don’t re-radiate as much heat back into the surrounding environment. (They have a “lower emittance.”) Combined, these two features increase the efficiency of solar collectors. Although selective surfaces cost a bit more, they’re well worth it, especially in colder climates where higher collector efficiencies dramatically boost solar hot water system performance.

— HELIODYNE

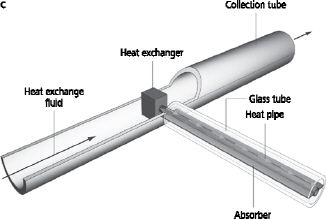

Evacuated Tube Collectors

Evacuated tube collectors, like those shown in Figure 3-8 a and b, are a relative newcomer on the solar hot water scene and are a serious departure from conventional flat plate collectors. These solar collectors consist of numerous (20 to 30) long, parallel glass or plastic tubes. Inside each tube is a copper pipe (absorber tube) coated with selective surface material. It runs down the center of an absorber plate, which increases the surface area for absorption. Air is pumped out of the glass or plastic tube, creating a vacuum, hence the name evacuated tube collectors. (Vacuums are poor conductors of heat and therefore great insulators.)

Inside each black copper pipe is a heat transfer fluid (typically methanol). It absorbs heat created when sunlight strikes the black selective surface of the absorber plate. Methanol flows upward naturally — by convection — to a heat exchanger at the top of the unit. Here, heat is transferred to another heat transfer fluid, typically a high-temperature non toxic antifreeze (propylene glycol). It carries the heat to a solar water tank where it is transferred to water and stored for later use. Cooled methanol returns to continue the cycle.

As Bob Ramlow, solar hot water expert and senior author of Solar Water Heating, pointed out to me in a personal communication, there’s a lot of hype about evacuated tube solar collectors so it is important to consider their pros and cons carefully. For example, the vacuum in a collector may help reduce heat loss, but it also reduces snow melt. In regions with frequent snows, these collectors shed snow poorly, especially when mounted parallel to a roof. Some collectors lose their vacuum, too, although some manufacturers have made changes in their design to prevent this.

Interestingly, numerous side-by-side comparisons have shown that evacuated tube collectors do not outperform flat plate collectors, either, despite manufacturer claims. Nor do they perform any better than flat plate collectors in “less-than-optimal regions.”

Fig. 3-8 a and b: Evacuated tube solar hot water collectors can be mounted on the roof of a building (a) or on the ground (b). Each evacuated glass tube in this collector houses a black absorber tube filled with methanol (c). Sunlight striking the absorber tube heats the methanol, which rises inside the tube, releasing heat in the heat exchanger, and then returns to repeat the cycle.

Evacuated tube solar collectors do produce higher temperature heat, which may work well in many baseboard hot water heating systems. As Ramlow noted, evacuated tube collectors will produce water as high as 220°F, compared to 180°F for flat plate collectors. Although this may seem advantageous, water can boil in the storage tank, a situation that typically happens when families go on vacation during the summer. Rarely will water boil in a flat plate collector system. To protect against this, you should strongly consider installing a larger storage tank with evacuated tube collectors.

“When investing in evacuated tube collectors, a buyer must pay particular attention to quality because while some of the highest rated collectors are evacuated tube type, most of the lowest rated collectors are also evacuated tubes,” Ramlow noted. “Each has its place and best and worst applications. While one is not better than the other, flat plate collectors dominate all markets except China where inexpensive, government subsidized, not freeze proof glass tube ICS systems dominate.”

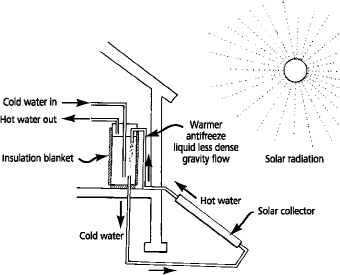

Thermosiphon Systems

Now that you know the types of solar collectors in use today, it is time to explore solar hot water systems with separate collection and storage. We’ll begin with the simplest of systems. The most basic solar hot water system is known as a thermosiphon system, shown in Figure 3-9. As you can see, this system consists of a collector, a storage tank, and pipes connecting the two. Notice, however, that there are no pumps, sensors, or controls in the system. There’s no need for them. Water flows through the system naturally by convection. How does this work?

Convection is the movement of a hot fluid such as air or water. As you may recall from high school physics, air and water both expand when heated. When they expand, they become less dense. This causes them to rise. In the process, they carry heat with them. But that’s not the end of the story. A liquid rising by convection creates a vacuum that draws fluid in; the result is a natural pump called a thermosiphon. Consider an example: sunlight striking the Earth heats its surface. Heat is transferred to the air above it, causing it to expand and rise. Hot air rising, however, creates a vacuum that draws cooler air in from neighboring areas to fill the void.

In a thermosiphon solar hot water system, like that shown in Figure 3-9, water rises in the pipes inside the collectors when heated, drawing cooler fluid in from elsewhere. The result is a natural pumping action, a convective loop. The convective loop propels the hot water into a solar storage tank in the house, where the heat is deposited. Cooler water from the bottom of the tank is drawn into the collector where it is heated.

The convective flow of liquid in this system is a simple, non-mechanical pump that operates throughout the daylight hours, stripping heat from the solar collectors and depositing it in the storage tank in the house. Thermosiphon systems are simple and elegant — and less expensive than the more complicated pump-driven systems, discussed shortly. Like solar batch water heaters, thermosiphon systems are not, technically speaking, active systems. They have no mechanical pumps.

Before you race out to buy such a thermosiphon system, however, there are several things to consider. First, note that the hot water tank must be located above the solar collectors by about two feet. This is the only configuration that will allow natural thermosiphoning to occur. As a result, solar hot water panels are typically mounted on the ground, slightly below the hot water tank, as shown in Figure 3-9.

Thermosiphon systems can also be mounted on roofs, so long as the water tanks are located slightly above the panels, for example, in an insulated space in the attic or in an upstairs room. Some tanks are even mounted on the roof themselves, although in most applications the tanks need to be very well insulated for this to work.

Thermosiphon systems use two types of heat transfer liquid: water, or a special nontoxic antifreeze, the food-grade propylene glycol, mentioned earlier. Water can be used as a heat transfer liquid in systems installed on homes in warm climates where freezing is not expected. Food-grade antifreeze is used in systems installed in colder climates where freezing is expected. As a rule, water systems are simpler, cheaper, and a bit more efficient, for reasons explained shortly.

Fig. 3-9: Convection drives the heat transfer fluid in this thermosiphon system, eliminating the need for a pump and electricity. Direct systems use water as the heat transfer fluid. Indirect systems use antifreeze as the heat transfer medium. Note the absence of a heat exchanger in this system.

In this type of system, water heated by the panels flows directly into the solar hot water tank. It is then drawn into the storage water heater or tankless water heater and used directly any time a faucet is turned on. This configuration is referred to as a direct or open-loop system. Antifreeze systems are more complicated, a bit more costly, and slightly less efficient than open-loop water systems. Efficiency suffers a bit and costs go up a bit because the antifreeze must travel through a heat exchanger in the first tank. The heat exchanger is typically a coil of copper pipe in the wall or in the base of, alongside, or inside the tank.

As the solar-heated liquid flows through the heat exchanger, heat is transferred from the propylene glycol to the water in the tank. Cooled antifreeze flows back to the panel to be reheated continuously during the day. This type of system is referred to as an indirect or closed-loop solar hot water system. (Because the heat transfer fluid does not mix with domestic hot water, it’s in a closed loop.)

PV-Powered Solar Hot Water Systems

If you are concerned about the electricity required to run the pump in a solar hot water system (to be honest, it’s really not that much) or if you want to go totally solar and simplify your system, you can run a solar hot water system off a small solar electric or PV module — a 30- or 50-watt PV. In such systems, a PV module is mounted next to the solar hot water panels and is wired to a DC pump. (PVs produce direct current electricity.) When the sun rises, the PV panels begin to produce DC electricity. Electricity flows to the pump, waking it up from its evening snooze. The pump begins to propel the heat transfer fluid through the collectors and pipes when they reach a critical temperature — preset by the installer so as not to circulate cold water through the system. Heat generated by the solar collectors therefore begins to flow from the panels to the storage tank. When the sun sets, the system shuts off.

PV direct systems are simple and cost-effective, and eliminate the need for sensors and controls that can break down. One manufacturer, Sol-Reliant, produces a sleek system with a built-in 35-watt PV panel. It is one of the easiest systems to install. You can learn more about it at solreliant.com.

Pros and Cons of Thermosiphon Systems

Open-loop thermosiphon systems are relatively simple, inexpensive, and relatively trouble-free. Closed-loop systems are a bit more complicated, in large part because of the addition of the heat exchanger and the use of propylene glycol as the heat exchange fluid. One of the problems with propylene glycol is that it begins to deteriorate at high temperatures, turning into an acidic sludge that can gum up the pipes. When this occurs, it needs to be drained and replaced, a job best reserved for a professional.

Pump Circulation Systems:Open- and Closed-Loop

Your next choice is a pump circulation system. This system is pretty similar to the thermosiphon system except that the force that moves the heat transfer liquid is a small electric pump. Most systems use AC pumps that run off household current, but, as noted in the sidebar, another very smart option is a DC pump powered by a small solar electric (PV) panel — so long as the pump doesn’t have to move water too high.

Solar collectors in pump systems are usually mounted on roofs, but can also be mounted on racks on the ground, so long as they are in full sunlight all year round. Solar hot water tanks are located inside homes, usually in basements or utility rooms next to the conventional water heater that is soon to be relegated to the status of backup water heater.

The small electric pump, which is located inside, forces the heat transfer liquid up through the panels and then back down to the thermal storage tank.

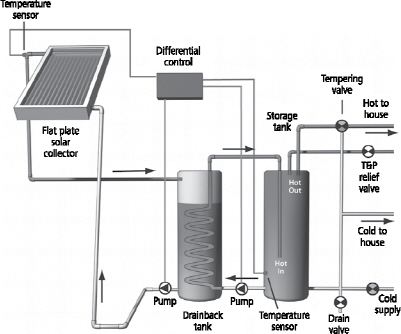

Closed-Loop Water Systems: Drainback System

Pump-driven systems may use water or propylene glycol as the heat transfer fluid. As in thermosiphon systems, discussed earlier, using water as the heat transfer fluid allows one to create an open-loop or direct system. Although open-loop systems have their advantages and may, therefore, seem desirable, there is a major challenge that must be overcome in colder climates: freezing.

Freezing is a problem because when water freezes, it expands, and not just a little bit. It expands quite a lot. Water freezing inside a copper pipe can create enough force to crack it wide open. Solar designers have solved this problem in two ways. The first is a draindown system. However, this type of system is not recommended by most of the folks I’ve talked to, so I won’t discuss it here. There is a viable alternative to the draindown system, a simpler trustworthy cousin, the drainback system (Figure 3-10). “Although similar in name to the draindown system,” writes Ken Olson, an expert on solar hot water systems, “the drainback system is far different and much more reliable.” Drainback systems rely on gravity to drain water from the pipes and panels when the circulating pump stops. When the sun stops warming the panels, a sensor signals the circulating pump to cease operation. Water flows out of the system into a storage tank. This is the type of system we installed in 2010 at The Evergreen Institute to heat water for the instructor residence and student kitchen and showers.

Gravity drainback systems are simpler than draindown systems because they have no motorized valves. This, in turn, reduces the possibility of system failure and deep freeze. Remember: in active solar systems, simplicity reigns supreme. The fewer the parts, the less likely the system is to malfunction — and the less maintenance will be required.

Fig. 3-10: This is a drainback system, generally recommended by solar installers over the draindown system. The drainback tank is generally much smaller than shown here.

Gravity drainback systems can be used in all climates and are less expensive and easier to maintain than other active systems. According to Greg Pahl, author of Natural Home Heating, direct-circulation, gravity drainback systems are “considered by many people to be one of the simplest and best systems to install.” They not only eliminate mechanical parts that can fail, they do not use propylene glycol heat exchange fluid which, as noted earlier, deteriorates over time and must be replaced every five years or so. Although a better option, these systems need to be designed and installed correctly to ensure complete drainage when the pump stops.

In some installations, like ours, only a single tank is used. Water circulates through the collector, then into and through an 80-gallon storage tank. When we turn on a hot water faucet, line water flows through 60-feet of copper pipe coiled inside the storage tank. This heat exchanger creates enough surface area so that line water is heated from 50 to 120 degrees as it flows through the pipe. (This is an on-demand solar hot water system.)

Pros and Cons of Drainback Systems

Drainback systems are simple, reliable, and less expensive than glycol-based systems, discussed next. They can be installed in cold climates and operate without propylene glycol (which comes with its own set of problems). They’re fairly easy to install, too, if you know what you are doing.

On the downside, these systems require the largest pumps of all solar hot water systems in use today. Also, care must be taken when installing the system to ensure that when the system shuts down, water flows freely back into the water tank. Be sure to use distilled water in the collector loop. Never use tap water, which contains minerals that can deposit on the inside walls of the pipes and collectors, obstructing flow.

Closed-Loop Antifreeze Systems

Many active systems in use today are pump-driven systems that employ propylene glycol, a food-grade antifreeze, as the heat transfer fluid. These systems are indirect or closed-loop systems (Figure 3-11). In order to prevent the mixing of the heat transfer fluid with domestic hot water, these systems require a heat exchanger to transfer heat from the antifreeze to the water in the solar hot water tank.

Closed-loop antifreeze systems require other components as well, some of which are not required in other DSHW systems. For example, as shown in Figure 3-11, closed-looped antifreeze systems require an expansion tank. Located in the antifreeze loop, it accommodates the expansion of the antifreeze as it heats up during normal operation, preventing pressure from building to dangerous levels inside the glycol loop portion of the system. When the antifreeze heats up, it expands, creating internal pressure. Rather than splitting the pipes open, excess is shunted into the expansion tank, reducing pressure. When pressure drops, the antifreeze empties from the expansion tank.

Fig. 3-11: This system uses a small electric pump to propel antifreeze (food-grade propylene glycol) through a closed loop. Heat from the antifreeze solution is released at the heat exchanger, warming water in the solar hot water tank. The heat exchanger may be next to the tank, as shown here, under the tank, or in the tank.

Closed-loop antifreeze systems also require a drain and fill valve, a valve that allows service personnel to drain the antifreeze and then refill it, respectively.

Pros and Cons of Pump Systems with Antifreeze

Closed-loop antifreeze systems are popular, well understood by those who have been in the industry for a while, and reliable. They work well in all climates, hot or cold, and in cold climates provide excellent protection against freezing. On the downside, closed-loop systems are the most complex of all hot water systems on the market today. They have more parts and, almost without exception, the more parts there are, the more chances there are for things to go wrong.

Another small downside of this system is that its use of a heat exchanger means that it functions slightly less efficiently than an open-loop pump-driven system in which water serves as the heat exchange fluid. In addition, propylene glycol needs to be replaced by a professional from time to time. This isn’t a job for most homeowners. Glycol becomes thick and sluggish if overheated, a problem that may occur as a result of pump or expansion tank failure or long power outages.

WHICH SYSTEM IS BEST FOR YOU?

Although there are a lot of options, it’s really not that difficult to select a system that will work for you. Get your felt tip marker out, as Ken Olson summarizes the options: “If you live in a freeze-free climate, you should choose a batch heater or a small thermosiphon unit.” Although these systems will only serve one to three people, you can always install a couple of batch heaters or thermosiphon solar collectors side-by-side to boost your hot water production. Or, says Olson, you should consider “an open-loop direct pump system circulating water from the storage tank to the flat plate collector.” That’s a drainback system.

In colder climates or in regions with hard water, Olson recommends “one of the closed loop systems with antifreeze and a heat exchanger.” A closed-loop antifreeze system is recommended in regions with hard water because hard water contains minerals that can deposit on the inside of pipes of open-loop systems. Over time, these minerals accumulate, reducing flow rates and the efficiency of an DSHW system. The open-loop water systems just aren’t worth it in such applications. Using water as a heat transfer medium in such instances, is going to cause you trouble.

SIZING YOUR SYSTEM

Sizing a DSHW system is pretty straightforward process. Before you get started, however, it is important to be sure you have a good solar site. That is, you need to be sure you can position solar collectors so that they’re exposed to bright sunlight from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. every day of the year. Fortunately, most homes, and even many apartments in cities, have good solar access somewhere on the site. Roofs are often free from obstructions that can shade solar panels.

If you have a good site, your next task is to scour your home for ways to make it more efficient with respect to hot water use. Remember: efficiency is the first rule of renewable energy system design! Make your home as efficient as possible, then size the system.

In his excellent article, “Solar Hot Water: A Primer,” published in Home Power magazine Issue 84, Ken Olson recommends the following steps to make your home more efficient (these were also mentioned in Chapter 2):

1. Turn down the thermostat on your water heater to 120° to 125°F (48° to 51°C). “Many water heaters,” says Olson, “are set between 140° and 180° F (60° and 82°C),” but much lower temperatures are just fine.

2. Wrap the water heater with an insulated water heater blanket.

3. Fix drips in faucets in the kitchen and bathrooms to prevent the waste of hot water.

4. Install water-efficient showerheads and faucet aerators to reduce hot water use.

5. Insulate hot water pipes in unconditioned space.

You can also enact various conservation measures, like taking shorter showers, washing dishes by hand and not leaving the hot water running, and washing clothes in cold water.

Once water and energy efficiency and conservation measures are in place, it is time to size your solar hot water system. The size of a system depends on many factors, the most important of which are (1) your climate — how hot, cold or sunny it is; and (2) your family’s water consumption. It also depends, in part, on your solar exposure. Will your system have unobstructed access to the sun from at least 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. each day? If not, you’ll need a larger system.

In the United States, most families consume 15 to 30 gallons of hot water per person per day for showers, baths, washing clothes, and dishwashing. By conserving water, you can easily slash daily water consumption to the low end of the range, about 15 to 20 gallons per day. Knowing a family’s daily water consumption, designers next turn their attention to daily storage capacity. If, for example, a family of three consumes 20 gallons per day per person, they’ll need 60 gallons of hot water storage to meet their needs. For most households of four, Olson recommends an 80-gallon hot water tank, based on daily water use of 20 gallons per person. Once you’ve determined storage capacity, you turn your attention to solar collectors. You will need to determine the number of square feet of solar collectors for your application.

Solar Pool Heating

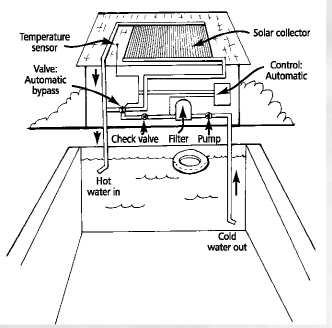

Got a swimming pool you’d like to heat with the sun? No problem. Solar hot water systems make great pool heaters. Solar pool heaters circulate water from the swimming pool to the panels and back again during daylight hours (Figure 3-12). These systems are about as simple as you can get. There’s no need for a heat exchanger, antifreeze, expansion tanks, or a hot water storage tank as in many DSHW systems. Sure, you will need sensors to switch the system on and off automatically each day, and you’ll need an electric pump. But you can avoid the sensors altogether by installing a PV panel that runs a DC pump, as mentioned earlier in this chapter. You’ll also need a few more panels than you would if you were heating domestic water.

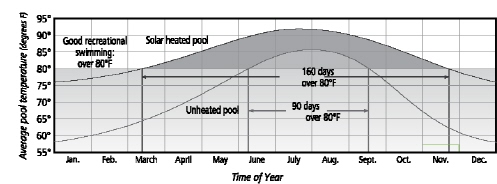

Solar hot water systems can warm our pools and lengthen the swim season substantially, as shown in Figure 3-13. And, if you like, you can even link the domestic solar hot water system with the pool heating system. Some homeowners have installed systems that heat their pools, their domestic hot water, and their homes. To learn more, I strongly urge you to read “Solar Pool Heating,” Parts 1 and 2, by Tom Lane in Home Power magazine, issues 94 and 95.

Fig. 3-12: (a) Swimming pools can be heated by the sun. Such systems not only provide warmer water, they can extend the length of the swimming season. (b) Diagram of solar pool heating system.

Conditions: 20-year average weather data for North Florida. 1,000 BTU per square foot per day of collector output for a pool in full sunlight; a screened-in pool would typically be 5°F lower year-round. Pool blanket used when night-time temperatures are below 60° F.

Fig. 3-13: This graph plots the water temperature in a swimming pool in northern Florida. As illustrated, solar pool heaters result in warmer water and also extend the length of the swimming season.

Once again, this process is pretty straightforward and highly dependent on solar availability and local climate. Generally, the sunnier and warmer the climate, the fewer square feet of collector you’ll need. The cloudier and cooler your region, the more square feet of collector you’ll need.

As a general rule, say the folks at AAA Solar in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the sunniest locations, like the desert Southwest and Florida, you’ll need about one square foot of collector for two gallons of tank capacity. Thus, for an 80-gallon tank, you’ll need 40 square feet of collector. (A single 4- x 8-foot collector provides 32 square feet of collector surface.)

In the Southeast and the mountain states, which are a little less sunny and, in the case of the mountain states, also a bit cooler, you will need one square foot of collector for 1.5 gallons of tank capacity. For an 80-gallon tank, then, you will need 53 square feet of collector. In the Midwest and Atlantic states, you will need one square foot of collector per gallon of tank capacity. An 80-gallon tank will therefore require 80 square feet of collector. In New England and the Northeast, which are the least sunny areas and pretty cold in the winter, you need one square foot per 0.75 gallons of tank capacity. An 80-gallon tank will then require 107 square feet of collector.

Solar systems designed to these general guidelines will provide about 100 percent of your domestic hot water needs in the summer, and about 40 percent in the winter, says Olson. If you want to obtain more hot water in the winter, you will need a larger system. But bear in mind that you will have a huge surplus in the summer.

Designers use these general guidelines to determine how many flat plate collectors are needed for a solar hot water system. Because all solar collectors differ with respect to their efficiency, be sure to consult with a local vendor or your supplier before you order collectors — if you are going to install the system yourself (this is not a project for individuals with little or no experience in plumbing and building). Remember, if you undersize your system, you can always add another collector later, if you have room for one.

FINDING A COMPETENT INSTALLER

Homeowners with considerable plumbing and electrical skills can install their own solar hot water systems. You can even make your own collectors, although I don’t recommend this approach for any system other than the batch heater, the simplest of all solar systems. I don’t mean to thwart creativity and independence, but as a general rule it is far better to purchase a reliable, well-built system and install it yourself or hire a professional to do the work for you than to build and install your own system.

Why not build your own solar hot water system?

Solar collectors are exposed to wind, hail, and extreme temperatures. They live a very difficult life up there on our rooftops. Over the years, manufacturers have made great strides in solar collector design and materials and are producing solar collectors that can withstand the harsh treatment Mother Nature doles out. It is unlikely that you could come close to matching the solar collectors on the market today. One of the trickiest aspects of solar design is selecting black paint or coatings to paint the interior of the collector. Although store-bought black paint might work well for a few years, it may vaporize. When paint turns to vapor, the vapor leaves deposits on the inside of the collector glass, impeding solar gain and making the panel look pretty ugly.

Unless you’re pretty good at plumbing and electrical work, you should probably let a professional install your system. They’re fast and experienced and will be done in the blink of an eye. For the homeowner, installation might take a full weekend interspersed with numerous trips to the hardware store to pick up plumbing supplies. A professional will have everything he or she needs in the truck.

If you do decide to install your own system, I recommend you check out the excellent series of articles published in one of my favorite resources, Home Power magazine. Issue 94 covers installation basics — information that applies to all pump-driven systems. Issues 85 and 95 cover closed-loop antifreeze systems, and issues 86 and 97 describe the installation of drainback systems. Home Power continues to publish many articles each year on solar hot water systems, so be sure to check more recent issues for the latest information.

THE ECONOMICS OF DOMESTIC SOLAR HOT WATER SYSTEMS

In “Solar Hot Water Primer,” published in Home Power, Issue 84, Ken Olson writes, “An initial investment in a solar water heating system will beat the stock market any day, any decade, risk free. Initial return on investment is on the order of 15 percent, tax free, and goes up as gas and electricity prices climb.” Although I share Ken’s enthusiasm for solar hot water, his endorsement is based on a comparison of a solar hot water system with a conventional electric storage water heater. Unfortunately, the economics don’t always work out that well, and homeowners need to be aware that the economics of the decision depend on many factors.

Let’s start by comparing a solar hot water system with an electric storage water heater. Clearly, as Olson indicates, a solar hot water system compares quite favorably with an electric storage water heater, especially if you are paying more than 8 to 10 cents per kilowatt-hour for electricity. Here’s how the math works out according to Olson: a typical 80-gallon electric hot water tank serving a family of four consumes approximately 150 million BTUs over its 7-year lifetime. If your electricity costs 8 cents per kilowatt-hour, hot water will cost approximately $3,600 in US dollars over that period. At the end of its short, useful lifetime, the water heater may need replacement, further adding to the cost. (To be fair, the water heater will very likely last a bit longer than Ken estimates, and there are ways to ensure a much longer life span, as noted earlier in this chapter.)

In such instances, solar hot water systems make eminent sense. If you live in a warm climate, you can purchase and install a solar batch heater for much less than $3,600. If you live in a colder climate, you can purchase and install a pump-driven antifreeze system for $5,000 to $6,000 minus a 30% Federal tax credit in the US, bringing the cost to $3,500 to $4,200 — depending on the type of system you select (flat plate vs. an evacuated tube collector). From that point on, you will be getting hot water essentially free of charge.

The economics of a solar hot water system may be even better if you live in a state or city or are served by a utility company that offers financial incentives that offset the initial cost of the system. In many locations, homeowners can receive substantial financial incentives that dramatically reduce the initial cost of a solar hot water system. The US Government currently offers a 30 percent federal tax credit for homeowners and business owners. Business owners can apply an accelerated depreciation schedule to a solar hot water system and can receive their tax credit immediately (within 80 days) by filing an application (grant) through the US Treasury Department. They can receive the tax credit as a grant even if they have no tax liability or their tax liability is lower than the tax credit. It’s not a bad deal — if you own a business.

Solar hot water systems also make economic sense compared to propane-fired water heaters. Propane is often used in rural areas to heat homes, provide cooking fuel, and to heat water. Although propane is not as expensive as electricity, it is still generally cheaper to generate hot water from a solar system than from a propane water heater, according to Alex Wilson, Jennifer Thorne, and John Morrill, authors of one of my favorite energy books, Consumer Guide to Home Energy Savings.

Because natural gas currently costs much less per BTU than electricity and a bit less than propane, solar hot water systems don’t always make financial sense compared to natural gas-fired hot water systems. (Although rising natural gas prices will clearly render this judgment obsolete soon.) When contemplating a DSHW system in a home served by natural gas, contact a local installer who can run the numbers for you. And, as one of Colorado’s premier solar architects, Jim Logan points out, in addition to installing a system to offset high natural gas prices, “you may want to do so to offset carbon dioxide emissions” that are causing devastating climatic changes. A solar hot water system is another way to put your values in action.

In closing, installing a solar hot water system is generally a smart move, and will very likely make more sense in more places as natural gas, propane, and electricity prices continue their upward spiral. With the information you’ve learned in this chapter, you can now proceed with confidence. I recommend that you select a solar system design that will work in your climate, and then shop around. Contact local suppliers/installers. See what they have to offer. Read up on each of their systems before you lay your money down. Talk to people for whom they’ve installed systems. Be sure to check the Better Business Bureau for any possible complaints about the company.

Good luck!