Many people heat their homes with wood. With the impending decline of two vital home heating fuels, natural gas and oil, wood is very likely to become even more popular, especially in rural areas. Many urban and suburban homeowners may find wood to be an economical source of primary or secondary heat — backing up conventional fuels or renewable home heat sources such as those discussed in the last two chapters. Although this may seem like an outlandish claim, you’d be amazed at how much wood is available in and around cities from tree removal, packing crates, and discarded pallets. You may even be able to grow some of your own wood for heat if your lot is big enough and you plant fast-growing trees such as cottonwoods.

This chapter offers some guidance on wood heat, a source I’ve used as both a backup and a primary heat source for decades. In this chapter, I will outline several options and provide information that will help you make sound economic and environmental choices.

RETROFITTING FIREPLACES FOR EFICIENCY

Many homes in North America have fireplaces, and many homeowners may be inclined to use them to provide heat. Before you stoke up the fire, though, consider these facts. First, fireplaces are one of the least efficient heating technologies humans ever invented. Most fireplaces achieve efficiencies of only 10 to 20 percent. In other words, only 10 to 20 percent of the heat generated by burning wood in a fireplace actually makes its way into adjoining rooms. Most of the heat is lost up the chimney. In fact, some fireplaces lose more heat than they generate! Second, fireplaces are sources of enormous heat loss in the winter, even when they are not operating. Moreover, cool indoor air leaks out of fireplaces in the summer, raising cooling costs.

Unless your home is equipped with an extremely efficient fireplace, close up your fireplace or install a fireplace insert in the opening (Figure 6-1). Fireplace inserts are steel boxes that fit into fireplace openings. Most models are about 70 percent efficient.

Fireplace inserts cost as much as wood stoves. Models vary considerably in their heat output, ranging from 30,000 BTUs per hour to nearly 85,000 BTUs per hour. The difference is related to their size and construction.

Fig. 6-1: Fireplace inserts are wood stoves that fit into fireplaces, dramatically increasing their efficiency.

When purchasing a fireplace insert, be sure to select a model that comes with a blower fan. Fans circulate room air around the combustion chamber of the insert, then force it out into the adjoining room, boosting the efficiency of the stove. For more information, you may want to consult John Gulland’s piece, “Woodstove Buyer’s Guide,” published in one of my favorite magazines, Mother Earth News.

FUEL-EFICIENT WOOD-BURNING STOVES

Free-standing wood stoves are another option for home heating. Wood stoves are widely available and come in a wide variety of shapes, sizes, colors, and materials. Let’s begin by looking at the three basic types: radiant, circulating, and combustion.

Radiant Wood Stoves

Radiant wood stoves are constructed of a single layer of metal — either sheet metal, cast iron, or welded steel (Figure 6-2). To protect the metal from heat damage and prolong the life of the stove, manufacturers typically line the combustion chamber with fire brick — a high-temperature brick that protects the metal.

Radiant stoves are so named because they warm rooms primarily via radiation: heat energy produced by the fire radiates off the hot metal surface of the stove. Heat is also stripped from the hot stove and circulated throughout the room by convection. Convection currents are created by the heat released from a wood stove. It warms room air near the stove. The hot air then rises. Cooler room air flows in to fill the gap. As the cooler room air flows near the stove, it is heated. The heated air rises, creating a convection loop that circulates heat through the room. Because heat may accumulate near the ceiling, some homeowners install ceiling fans to blow heat down, assisting natural convection.

Radiant stoves constitute the bulk of the wood stove market because they are simpler than the next major type, the circulating stove, and use less material. Their sparing use of material makes them less expensive to manufacture and hence less expensive to buy. Some cast iron radiant stoves are an exception; they can be quite costly due to more extravagant design (Figure 6-3).

Besides being fairly economical, radiant wood stoves are fairly efficient — with combustion efficiencies in the range of 70 to 80 percent.

When shopping for a radiant wood stove, look for models that allow you to control the flow of air into the combustion chamber. Controlling the amount of air entering the combustion chamber allows the operator to regulate the rate of combustion. The more air that’s allowed into the combustion chamber, the hotter the fire. Because hotter fires also burn out more quickly and often generate more heat than is necessary at any one moment, air flow controls allow the homeowner to regulate heat output. Many stove users restrict the air flow to the combustion chamber once the fire has been started and is burning strong. This ensures a good, long, steady burn and helps prevent a room from overheating. Be careful, though, not to turn the air flow down too far. This can cause inefficient burning and other problems described in the accompanying sidebar.

Fig. 6-2: Radiant wood stoves like this model from Travis Industries are made from cast iron or welded steel.

Fig. 6-3: This cast iron radiant wood stove from CFM Majestic is attractive and efficient.

Fig. 6-4: Circulating wood stoves feature double-wall construction. They’re a bit more expensive than radiant wood stoves.

Creosote and Other Considerations

Many stove operators like to turn their wood stoves down once they’ve gotten sufficiently hot. Unfortunately, reducing the flow of air into the combustion chamber reduces the combustion efficiency of the stove. Restricting the air supply may cause a fire to smolder and produce more air pollution, especially particulates and carbon monoxide. In addition, volatile gases from the wood escape up the chimney unburned. These organic chemicals are often deposited on the walls of the flue pipe, forming dreaded creosote. If not periodically removed from the flue pipe, creosote may catch on fire, burning at a searing 2100°F (1150°C). These extremely hot fires can spread to the house.

As you shop, you will find that some wood stoves come with automatic controls. They allow the operator to set the desired room temperature; the stove then regulates air flow into the fire to maintain it. Vermont Castings’ Encore wood stove is an example. This stove is also designed for smokeless top loading and has a removable ash pan for ease of cleaning — convenience features many homeowners find appealing.

Circulating Wood Stoves

The second type of wood stove is the circulating wood stove (Figure 6-4). Circulating wood stoves look like ordinary wood stoves. However, upon closer examination you will notice one striking difference that affects both price and performance. Circulating stoves are double-walled. The combustion chamber is constructed of cast iron or welded steel and is typically lined with fire brick. The outer shell is typically made from a lightweight sheet metal. Separating the two is a small air space. When the fire burns inside the stove, heat is transferred to the inner shell. This heat is removed by room air that circulates through the air space either passively (by convection) or actively (by a fan). The hot air is then vented into the room. Heat also radiates off the outer shell, but the double-walled construction prevents the outer metal layer from getting as hot as the surface of a radiant stove. This is important for safety. Thus, although circulating stoves cost more, they provide a slightly greater measure of safety, which is especially important for families with young children who might be inclined to touch a hot stove out of curiosity or who might stumble and fall against the stove. (All wood stoves should be “fenced off ” from young children.)

Like radiant wood stoves, circulating stoves achieve efficiencies in the range of 70 to 80 percent, depending on the design.

Combustion Wood Stoves

Last, and certainly least, is the combustion wood stove. The old-fashioned Ben Franklin stove is a good example. Combustion stoves are radiant wood stoves with one significant difference: the doors can be opened when the fire is burning. Opening the doors converts the combustion wood stove into a fireplace slightly more efficient than a standard fireplace.

Where’s the Heat?

You may be surprised to know that half to two thirds of the fuel value of wood is locked up in gases and volatile liquids. When a piece of wood is burned, for example, only 30 to 50 percent of the heat comes from combustion of the solid woody fibers. The rest comes from the combustion of hydrocarbons, if your stove burns hot enough to ignite them.

From The Solar House: Passive Solar Heating and Cooling, by the author.

Open doors provide a view of the fire, which many find desirable, but they allow a huge amount of air to enter the combustion chamber. As a consequence, the fires tend to burn much hotter. Also, and perhaps more importantly, much of the heat generated in the combustion chamber is lost up the flue pipe. Therefore, combustion stoves achieve efficiencies in the range of 50 to 60 percent, depending on the amount of time the stove is burned with the door open.

In an energy-short world, combustion stoves should be avoided. If you want to see the fire, purchase a radiant or circulating wood stove with a glass door, a feature offered by most wood stove manufacturers.

SHOPPING FOR AN EFICIENT, CLEAN-BURNING WOOD STOVE

If you live in the country and have a ready supply of wood, or if you live in an urban or suburban setting and have access to lots of wood, a wood stove may be a very wise investment. As is the case with all renewable technologies discussed in this book, you will need to shop carefully. There are a lot of models on the market. So what do you look for?

I strongly recommend that you shop for efficiency. The higher the efficiency, the better. As you might suspect, efficiency and cleanliness go hand in hand when it comes to a wood stove. A stove that wrestles as many BTUs out of the wood as possible also typically produces the least amount of pollution.

Be patient and research your options carefully. Visit as many dealers as you can and ask lots of questions. Be wary of claims that seem too good to be true.

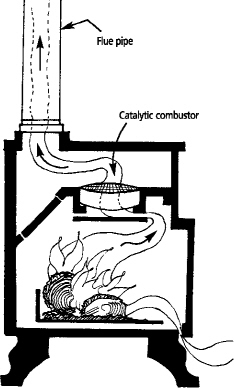

Fig. 6-5: Catalytic burners in wood stoves increase their efficiency and reduce air pollution.

Wood Stoves with Catalytic Converters

One of the first questions you will face when shopping for a wood stove is whether or not you should purchase a stove with a catalytic converter. To meet the clean air requirements of many cities, wood stove and fireplace insert manufacturers have equipped their products with catalytic burners (Figure 6-5). Catalytic burners contain a ceramic honeycomb structure coated in palladium or platinum (the catalyst). Like the catalytic converter in a car, the catalytic burner completes the combustion of unburned hydrocarbons — the gases escaping from the wood. (Remember, these gases ignite at a higher temperature than most wood stove fires provide, so unless there’s a catalytic burner or combuster, the energy in these gases will be lost.)

Wrestling more heat from the wood by burning these gases boosts a stove’s efficiency. Catalytic converters improve wood stove efficiency by 10 to 25 percent. Increasing efficiency not only means you get more heat from the wood you buy or collect, it means you will burn less wood and spend less time and money heating your home. It also reduces creosote buildup and the problems it creates. According to several sources, catalytic burners pay for themselves in two years, give or take a little.

Catalytic burners are located in chambers above, behind, or below the main combustion chamber. Because catalytic burners burn the gases and liquids that escape from firewood, these devices reduce creosote deposits on flue pipes by 80 percent or more, reducing the risk of house fires. Less creosote buildup also reduces cleaning costs.

Although catalysts are a great idea, they do have some drawbacks. One of them is that they don’t last long. The life expectancy of new catalytic burners is only about three to six years. Yet another disadvantage is that they don’t work well at higher elevations (according to the wood stove dealer near my former home in the foothills of the Rockies in Colorado).

How Wood Stove Catalytic Converters Work

Combustion is a chemical reaction between oxygen and organic materials triggered by heat.

Combustion temperatures inside a wood stove are normally only around 400° to 900°F (204° to 482°C), well below the normal combustion temperature of hydrocarbons. Wood stove catalytic converters dramatically lower the ignition temperature of hydrocarbons released from the fire from 1100°–1300°F (593°–704°C) to around 600°F (315°C). (Catalysts speed up the rate of chemical reactions by lowering the temperature at which they occur.)

Although catalytic burners start out burning at low temperatures, internal temperatures within a catalytic converter climb to 1700°F (926°C) or more pretty quickly. This is much higher than the temperature required to burn the gases and liquids released by firewood. Once the catalyst reaches these temperatures, it generates its own heat and will maintain temperatures sufficient to burn off hydrocarbons, even when the air supply to the stove air is restricted to prolong the burn time. Thus, even though a reduction in air flow creates a less efficient, cooler fire that releases more unburned hydrocarbons than a high-temperature fire, you don’t need to worry about losing energy from your wood or polluting the atmosphere. Once the catalyst reaches temperature, it remains very hot.

Catalyst-Free Stoves

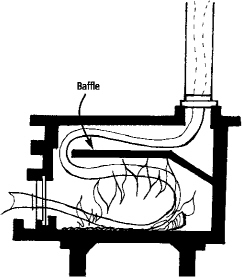

Fortunately, many wood stove manufacturers have found an alternative to the catalytic converter, one that’s cheaper in the short term and the long term. These designs utilize a baffle that forces combustion gases released from the fire — including unburned hydrocarbons — back over the flames, causing them to ignite and burn (Figure 6-6). This process is typically referred to as secondary burning. Baffles increase combustion efficiency, in part, by increasing air turbulence. Greater air turbulence puts unburned hydrocarbon gases in contact with air and heat. The greater the mixing of these “elements,” the greater the efficiency. Baffled wood stoves burn cleanly and achieve high efficiencies — on par with wood stoves equipped with catalytic combusters — and they’re usually a bit cheaper.

Fig. 6-6: Baffles in wood stoves increase their efficiency and reduce air pollution.

Should You Buy a Used Wood Stove?

Those inclined to save a little money may think about buying a used wood stove. Is this a good idea?

Not usually.

Although a used wood stove may be inexpensive, older models are often pretty inefficient. Being inefficient, they also produce a lot more pollution than newer models. Older models, for instance, produce 30 to 80 grams of particulate matter per hour. Newer models produce 90 percent less, or about 3 to 6 grams per hour. Even though you may save upfront, you’ll burn more wood, spend more time tending the fire, and pollute more. You’ll also need to clean your flue pipe more often.

What Else to Look for when Shopping for a Wood Stove

When shopping for a high-quality, clean-burning, energy-efficient wood stove, there are a number of features to look for besides those just mentioned — features that help you obtain the most efficient, safest wood stove on the market.

First on the list is durability. Durability is a function of the material from which a stove is made. Cast iron and welded steel are best. Stay away from stoves made from sheet metal. Although they are inexpensive, stoves built entirely out of sheet metal are typically designed only for occasional use and won’t last very long if burned frequently. Thus, a sheet metal stove is a very bad investment for those who want to heat their homes with wood. Stoves made from one quarter inch thick, or thicker, steel plates that are welded together last a lifetime. Although the steel may warp a bit over time, steel stoves are durable and function year in and year out, without a problem.

Cast iron stoves, as just noted, are also a great choice. Some people consider them the best wood stoves on the market. Cast iron stoves do not warp like steel stoves and may last longer. However, despite its greater fire tolerance, cast iron is more brittle than steel. What this means to you is that a cast iron stove may crack if it is not shipped and installed with care. (Inspect a cast iron stove carefully for damage before firing it up the first time.)

Cast iron stoves can be coated with a durable, lustrous porcelain finish, adding beauty. However, cast iron stoves are typically the most expensive of all your options.

When shopping for a wood stove for your home, be sure to look for models that come with firebrick or ceramic tile linings. These materials shield the metal of wood stoves from high temperatures, increasing the stove’s life span. They may also increase the temperature of the fire, which can increase combustion efficiency. You should also consider buying a wood stove that preheats the air delivered to the combustion chamber. Preheating usually occurs in pipes or channels inside the stove. They transport incoming air in such a way that it can be warmed before it reaches the fire. This helps to maintain a hotter fire, and results in higher combustion efficiency.

Another highly desirable feature is a tight door seal. Good door seals help to prevent pollutants such as carbon monoxide from escaping from the combustion chamber and poisoning you and your family. A leaky door lets too much air into the combustion chamber, making it harder to regulate the combustion temperature and burn time.

How Big Should Your Stove Be?

When shopping for a stove, you will also need to consider its size. This depends on the size of your home and its energy efficiency, notably the level of insulation and air leakage. (Be sure to make your home as energy efficient as possible upfront.)

Fortunately, wood stove manufacturers offer a fair amount of information on their products that can help you make an intelligent choice. Unfortunately, there’s no set standard, so manufacturers use different methods to rate their stoves. This makes it more difficult to compare products. Some wood stove manufacturers, for example, provide data on the heat output of their stoves, measured in BTUs per hour, while others list the number of rooms or the number of square feet their stoves are designed to heat. Still others list the cubic feet of room space their stoves will heat. Unless you know the precise conditions under which the stoves were tested (for example, the type of wood and the insulation levels in the test facility), data such as these may not be relevant to your home.

Personally, I think that your best bet is to ask a reputable local supplier who is familiar with the heating requirements in your area. Be sure he or she visits your home. If you have upgraded the insulation in your walls and ceilings, sealed your house, and taken other measures to reduce heat demand, be certain the supplier knows this. If not, you may end up buying a model that is larger than you need.

Installing a Stove for Optimal Performance and Safety

Wood stoves need to be strategically placed for optimal performance and safe operation. Here are some general guidelines for installing a stove.

Choose a Central Location

When selecting a location for a wood stove, it’s best to avoid placement against an exterior wall. That’s because heat from the stove will warm up the interior surface of the wall, causing heat to flow out of the house. (Remember: heat flows from hot to cold.) Warming the inside wall increases the temperature difference across the exterior wall; the greater the difference, the greater the heat loss.

The best spot for a wood stove is in the center of the space you’re trying to heat. A central location ensures that heat from the stove spreads naturally throughout the house by convection and radiation. If you are concerned that heat won’t flow well, you can always install a ceiling fan or two to move heat around, provided that your ceilings aren’t too high (over 16 feet). Be sure to locate a wood stove so that it can be easily and economically vented to the outside.

Protecting Against House Fires

Safe installation also requires placement of the stove and flue pipe the proper distance from combustible materials in floors, walls, and ceilings to prevent fires. Safe installation also requires the use of heat-resistant materials that shield the floor and the walls from the intense heat of the stove. Most stoves are installed on a tile base either purchased with the stove or made yourself. Tile, metal, or other noncombustible materials are often placed on the wall behind the stove. Details of safe installation are beyond the scope of this book, so be sure to check your local building code and recommendations from your insurance company. Professional installers know the codes and can save you the trouble of having to learn them.

PROS AND CONS OF WOOD STOVES

Wood stoves are widely available and are easy to use. They are also relatively easy to install, although professional installation by a competent crew is highly recommended (see the accompanying sidebar, “Installing a Wood Stove”). Many people choose wood stoves because they are one of the least expensive heating systems. You won’t need the extensive and costly heat distribution systems required for conventional heating systems like forced hot air or radiant floor systems. Because there are so many suppliers and retail outlets in most locations, careful shoppers can usually get a pretty good deal on a wood stove, especially if they buy during the much slower summer season. Wood stoves are available in many different models, with many shapes, styles, and sizes to choose from. They can be used to heat a room or an entire home. The larger the home, of course, the larger the wood stove you’ll need.

Further adding to their appeal, wood stoves require very little cleaning or maintenance. For an older model, a good, hot, cardboard fire once every few months or an annual cleaning of the stove pipe usually suffices to remove all creosote, greatly reducing the chance of a chimney fire that could spread to the home. New models require less cleaning because they burn so much cleaner, but don’t get lazy. Flue pipes still need to be cleaned from time to time.

Many modern wood stoves are nice looking. Some models with glass doors allow you to view the fire, further adding to their appeal.

If you are concerned about air quality, remember that new wood stoves burn pretty clean. In fact, all new wood-burning stoves, except cook stoves, currently sold in the United States and Canada must comply with government regulations aimed at reducing urban air pollution. In the United States, the EPA sets standards for wood stoves. In Canada, the Canadian Standards Association has developed emission standards for wood stoves, fireplace inserts, and small fireplaces. Stoves certified by these agencies reduce smoke pollution by as much as 90 percent when compared to older models.

And, if you live in an area that imposes wood-burning bans on high-pollution days, you may be surprised to learn that EPA-approved stoves burn so cleanly that they are exempt from these bans. EPA Phase II stoves produce almost no smoke at all.

But what about carbon dioxide emissions from wood stoves and global warming?

Burning wood in a wood stove produces carbon dioxide to be sure. It’s unavoidable. All organic matter that burns produces this greenhouse gas. However, unlike coal or natural gas or oil, wood is a renewable resource. As long as we plant trees to replace those that we cut down and burn, wood burning should not increase global carbon dioxide levels. (However, cutting wood with a chain saw and transporting wood in a vehicle powered by gasoline or diesel will release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.) If you are cutting your own wood, replant trees. If you are buying from a local supplier, be sure to purchase from those who are good stewards of their forests and are actively involved in replanting, too.

Outside Combustion Air

Some states, like the state of Washington, require that all new wood stoves draw their combustion air from outside the home. This is designed to prevent backdraft — air being drawn down the chimney into the wood stove and then into the house when vent fans are being used inside a house. Why does this occur?

Vent fans create negative pressure inside the house that draws air in from any source it can. The flue pipe of a wood stove is a good source of replacement air. Backdraft of this nature may cause smoke and other pollutants from a smoldering fire to enter the home, creating a potentially dangerous situation.

To prevent this problem, combustion air for a wood stove can be brought in from the outside by creating an opening in the building envelope. It delivers cool outside air to the wood stove via a pipe. To be effective and safe, a system for supplying outside air must be carefully designed. Powered make-up air systems are probably your best bet. They are air systems that rely on a small fan to blow outdoor air into the stove. They only operate when the stove is in operation, and thus help prevent cold air from entering your home. Be sure to get professional help on this aspect of installation.

Another benefit of wood stoves is that they’re fueled by a renewable resource. If sustainably managed, wood lots can provide a lifetime of fuel to a family without damaging the environment. (To learn ways to harvest safely and sustainably, you may want to read The Good Woodcutter’s Guide by Dave Johnson.)

Harvesting woodlots can even benefit forests. For example, thinning woodlots reduces crowding and competition among trees for limited water supplies. Trees that are less crowded are healthier and better able to resist insects and other pests.

Wood burning is also economical. A cord of wood yields the same amount of useable heat as 200 gallons of heating oil, a ton of hard coal, or about 4,000 kilowatts of electricity. A cord of wood costs about $150, depending on your location and the type of wood. With home heating oil running around $2.80–$3.00 a gallon at this writing, 200 gallons of heating oil would cost about $560–$600. At 8 to 10 cents per kilowatt-hour, 4,000 kilowatts of electricity would cost $320–$400.

Wood burning does have some downsides. First and foremost, heating with wood may require a lot of work, especially if you are cutting from your own woodlot. You’ll have to fell dead trees, trim off limbs, cut up the wood, haul it to the house, split it, and stack it. Even if you purchase unsplit logs that are delivered to your home, you’ll be spending a lot of time cutting and splitting firewood. And don’t forget, you’ll be hauling wood into the house on cold winter nights, lighting fires, and tending to them. You’ll be cleaning up bark and debris that inevitably drop on your floor and cleaning the ashes out of the wood stove every week or so, and then disposing of them. (Cooled ashes can be spread on your property to return inorganic nutrients to the soil.)

Although hard work is good for the body, and many people enjoy it, especially if it helps increase self-reliance, wood heat is more than many people want to deal with. You may want to consider purchasing firewood. Many companies deliver it to your home and some will even stack it for you — for a price, of course. Or you may want to consider a pellet stove, discussed shortly.

But those are not the only downsides of wood burning you should be aware of before you set off on this venture. As environmentally benign as wood is, it can cause indoor air pollution. As noted earlier, smoke may escape from a wood stove as a result of backdraft. Smoke may also escape when a stove is improperly opened, or from leaks, and can result in unhealthy indoor air. In recent field tests of Canadian homes, varying degrees of combustion spillage from assorted furnaces, fireplaces, and wood stoves were detected in an alarming percentage of the homes tested. Soot deposits on walls, ceilings, and drapes are not only a nuisance, they are a sign that the air is polluted with potentially harmful particulates. Wood stoves, even clean-burning models, contribute to ambient air pollution.

Yet another potential problem is that wood stoves tend to produce really hot, dry heat that may lead to uncomfortable interiors. This can be rough on sinuses and nasal passages.

Wood stoves also tend to create a heat gradient in a home. The hottest room is the one in which the stove is located. Outlying rooms are typically much cooler. Because most wood stoves don’t come with fans to force air out and away from the stove, you may need to provide some way to better distribute heat. Many homeowners use ceiling fans or strategically placed small portable fans or box fans.

Wood heat may also be problematic in homes with cathedral or vaulted ceilings, a feature in many newer homes. Tall ceilings are a problem because heat from a wood stove rises and accumulates near ceilings — far away from the occupants. Although ceiling fans help to force the warm air back down, you will very likely end up burning more wood to achieve a comfortable room temperature. The more wood you burn, the more it costs, and the more pollution you produce. Second-story rooms or lofts may overheat, too, as a result of this phenomenon.

Remember, too, that because wood stoves require tending, they can’t supply backup heat when you are away from home for any length of time. Only the automated pellet stoves will keep a home warm when you’re away — so long as the pellet supply in the hopper lasts. (More on this shortly.)

In new construction, building departments rarely approve a wood stove as a primary heat source. You will most likely need to install an automatic wall heater, a furnace, or some other conventional heat source controlled by a thermostat. In existing homes, that’s not a big deal. You probably already have a conventional heat source that you’re trying to marginalize by using wood heat. Your furnace or boiler can be relegated to serve as a backup heat source.

Wood stoves can also be a fire hazard if improperly installed and maintained. Unfortunately, many houses go up in flames each year as a result of either poor installation or inadequate stove maintenance.

Another important consideration is that wood stoves are not as efficient as other forms of backup heat. For example, a wood stove isn’t as efficient as a high-efficiency furnace or boiler. That said, wood is a renewable resource, while oil and natural gas, two conventional home heating fuels, are not. Even though wood stoves may not be as efficient as conventional heat sources, they are still cheaper. To learn more, you may want to read John Gulland’s piece, “Responsible Wood Heating” in Home Power magazine, Issue 99.

WOOD FURNACES

Another renewable option for home heating is a wood furnace. Wood furnaces are typically installed in basements, garages, or even, as you will soon see, outdoors. Wood furnaces can be used in conjunction with a conventional home heating system, for example, radiant floor heat, baseboard, or forced-air heating systems. The Lynndale and Yukon Eagle wood furnaces, for instance, contain blower fans that move air generated by burning wood in them through the ductwork of forced-air heating systems in homes (Figure 6-7). Some companies also design their furnaces to preheat domestic hot water. During the winter, these units not only heat the home, they provide hot water for washing dishes and other household tasks, greatly reducing natural gas or electricity consumption.

When shopping for a wood-burning furnace, be on the lookout for various features that improve combustion efficiency. Combustion air blowers, for instance, are fans that force a stream of air into the fire, increasing combustion efficiency. Secondary combustion chambers, like those found in wood stoves, also increase efficiency. A secondary combustion chamber increases efficiency by burning gases released from wood during combustion. In some furnaces, secondary combustion chambers are designed so that they have their own air supply, that is, a supply of air in addition to that provided to the main combustion chamber. This feature also promotes greater combustion efficiency.

Increased efficiency, of course, means you’ll need less wood to heat your home. It also means your furnace will produce less pollution. Cutting down on pollution (soot and unburned hydrocarbons) helps keep the air in our cities and towns cleaner, and also has a very direct benefit to homeowners: it reduces creosote buildup in the chimney, reducing fire potential. This, in turn, reduces the need to clean the chimney as often, saving you money in the long run.

Some wood furnaces are designed to be used in conjunction with conventional fuels, ensuring that your home will be heated when you are gone for extended periods of time. Summeraire, a company in Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, for instance, manufactures a wood furnace that can be used in conjunction with home heating oil, natural gas, or propane. This dual-fuel furnace helps to prevent pipes from freezing when a homeowner is gone for extended periods.

Fig. 6-7: The Lynndale wood furnace.

Wood furnaces offer many advantages. They are pretty efficient and clean-burning. Some, like the wood furnace in the residence at The Evergreen Institute, take logs up to five feet long, which reduces labor. Wood furnaces also use a renewable resource and are fairly easy to operate.

On the downside, wood furnaces are much more costly than wood stoves and more difficult to install. They also require large fans to distribute hot air through the duct work of a home. Fans consume electricity, and they are often pretty noisy. And don’t forget, you will need to periodically load wood and remove ashes from the furnace. Wood furnaces, like many home heating technologies, also present some fire hazard if not properly installed and maintained.

Those who like the idea of a wood furnace but don’t have room to install one in their home — or don’t like the idea of hauling wood to the basement during the winter — may want to consider an outdoor wood furnace.

A handful of companies produce outdoor wood-burning furnaces. Central Boiler in Greenbush, Minnesota, for instance, manufactures a line of high-efficiency outdoor furnaces. They’re made from heavy-gauge carbon steel and titanium-enhanced steel (Figure 6-8). These furnaces look like a shed and can be placed as far as 500 feet away from a home or business. They burn wood to heat water, which is then pumped to the building through buried insulated pipe.

Fig. 6-8: Central Boiler’s outdoor wood furnace supplies hot water to the house that can be used in conjunction with radiant floor, baseboard hot water, and even forced-air heating systems.

Outdoor furnaces are typically used in conjunction with radiant floor, baseboard hot water, or forced-air systems. However, they can also be used to supply domestic hot water in the winter, when they’re running day in and day out.

Another well-made outdoor wood furnace is manufactured by HEATMOR in Warroad, Minnesota. These furnaces come in a variety of colors to match your house or to blend with the environment. Their furnaces are easy to load and maintain, and efficient to operate. They use a heavy-gauge steel that the manufacturer claims long outlasts its competitors’.

PELLET STOVES

If cutting firewood and hauling wood into your house all winter long isn’t your cup of tea, you may want to consider a pellet stove (Figure 6-9). Pellet stoves are much like wood stoves, but easier and cleaner to operate. (I think of pellet stoves as the lazy man’s — or lazy woman’s — wood stove.) Pellet stoves are free-standing stoves that provide space heat. They burn wood, but not bulky pieces of firewood. Instead, they are fueled by dry, compressed wood pellets. The wood pellets are made from sawdust that is a waste product of the timber industry.

Sawdust, from milling trees to produce finished lumber, was once burned at local wood mills throughout North America in huge incinerators. They smoldered for days, producing tons of smoke that dirtied the skies of many otherwise pristine rural areas. Today, many of these facilities convert their waste into small pellets, resembling rabbit feed, and sell it to eager customers throughout Canada and the United States. This trade has not only helped bolster local economies, it has provided a clean-burning fuel source for millions of people across the continent.

Pellets are packaged in 40-pound bags and are sold in hardware stores and many large discount stores. You can purchase a single bag or buy pellets by the ton to save money. At home, pellets are typically stored in a dry place, either in the garage or basement or under a waterproof tarp in the backyard. Pellets are loaded into a hopper that automatically feeds them into the combustion chamber by a screw auger powered by electricity.

Because pellets are dry, and because they are fed into the combustion chamber at a controlled rate with plenty of air, these stoves burn very efficiently and cleanly. In fact, they’re cleaner than most wood stoves.

Pellet stoves offer many of the advantages of a wood stove with fewer downsides. As just noted, they burn a renewable fuel, which is a waste product. By burning wood pellets, you’re helping reduce pollution in rural areas where mills are located. You’re also helping to support the wood products industry.

Fig. 6-9: Pellet stoves are the lazy person’s wood stove. They’re clean burning and operate automatically.

Another advantage of pellet stoves is that the operator can set the rate at which pellets are fed into the combustion chamber. This regulates the heat output of the stove. Yet another advantage of pellet stoves is that they come with fans that blow hot air from their surface into the room. This helps distribute heat throughout the house.

Pellet stoves are easier to load and not as messy as wood stoves. Another huge advantage is that they operate automatically, providing heat while you are gone, although usually no longer than a day or two. Many pellet stoves can be thermostatically controlled. And pellet stoves also allow for more precise control over heat production than wood stoves.

On the downside, pellet stoves require electrical energy to operate the auger and the blower fans that come standard on many models. In addition, pellet stoves usually cost more than similarly sized wood stoves, and they require more service. Wood pellets cost more than firewood, too. You’ll generate a lot of plastic waste from the empty bags, but you can use these for trash bags, if you like.

Fig. 6-10: Masonry heaters burn wood efficiently and provide a steady supply of heat. The masonry heater is an ideal heating system for homes, though they are difficult to install in existing homes.

MASONRY HEATERS

Between about 1550 and 1850, Europe was gripped by an intense cold spell. Historians, in fact, often refer to this period as the Little Ice Age. At the beginning of the Little Ice Age, homes and buildings in Europe were primarily heated by wood. However, wood was burned in inefficient fireplaces, simple stoves, and braziers. Inefficient wood-burning, in turn, led to widespread shortages of wood. But like many problems, this one led to a happy ending. Shortages led to the development of masonry heaters, highly efficient wood-burning stoves that greatly cut back on wood use. Not only did masonry heaters use less wood, they also produced greater comfort. Masonry heaters were so successful that, by the end of the Little Ice Age, nearly every building in Europe was heated by one (Figure 6-10).

Masonry stoves are still in use in northern Europe. Not just in old buildings, either; they’re often installed in new ones. In Finland, for example, 90 percent of all new homes are heated with masonry stoves — thanks, in part, to generous tax incentives offered by the forward-thinking and conservation-minded government. Masonry heaters are also very popular in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Germany, where they are highly regarded for their excellent efficiency, reduced pollution output, and safety. Because they offer so many benefits, masonry heaters are even starting to make their way into new homes in North America as primary and secondary heat sources. I think they could be an essential element in our transition to a renewable energy future, especially in new housing stock in rural areas, for reasons you’ll soon understand.

What is a Masonry Heater?

Masonry heaters are massive wood stoves typically made from bricks and mortar (Figure 6-11). Many masonry stoves are free-standing structures that are located in the center of the heated space so they can radiate heat outward in all directions. In some homes, masonry heaters serve as room dividers, providing heat to rooms on either side of them. Although many masonry stoves are free-standing (the most efficient installation), some stoves are built against outside walls.

Masonry heaters are designed to burn much hotter than wood stoves, which enables them to wring more heat from wood than even the most efficient wood stoves. They therefore require much less wood than a standard wood stove. Masonry heaters are also designed to emit a lower temperature heat, and release it steadily over many hours. To understand how all of this is possible, let’s peer inside a masonry heater to see how it works.

The main reason masonry heaters operate so efficiently is that their fireboxes are designed to burn wood at extremely high temperatures by ensuring ample air flow. Most designs also maximize turbulence in the firebox, which also increases combustion efficiency. As in wood stoves, the combustion chambers are lined by firebrick. Firebrick protects the rest of the masonry heater from the intense interior temperatures and also provides a greater level of insulation. This, in turn, holds heat in the firebox. By preventing heat from dissipating from the combustion chamber, internal temperatures can get quite high — in the range of 1200° to 2000°F (650° to 1095°C).

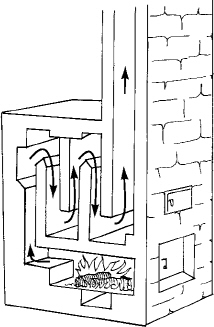

Fig. 6-11: The super-efficient masonry heater relies on three features: a well-insulated combustion chamber, a labyrinth flue, and high mass.

High-temperature combustion in a masonry heater results in the complete, or nearly complete, combustion of wood, including all of the gases and liquids driven out of a piece of wood after it catches fire. Masonry heaters, in fact, achieve efficiencies ranging from 88 percent to nearly 95 percent. (Wood stoves achieve efficiencies in the range of 70 to 80 percent.)

A hot-burning fire results in greater efficiency and also eliminates creosote buildup in the flue system. And it reduces air pollution. Like Phase II wood stoves, masonry stoves burn so cleanly, they’re approved for use when wood-burning bans are in effect, even in several areas in the United States known for tough wood-stove standards, like Colorado, Washington, and San Luis Obispo County, California.

Another important feature of masonry heaters is the often huge amounts of thermal mass provided by the masonry materials from which they’re built. These stoves are the leviathans of the heating world, weighing from one to eight tons.

How Clean Are They?

Masonry stoves are in the super-low emissions category of wood-burning devices because they release only 1 to 2 grams of particulates per hour. Many wood-burning stoves release 3 to 6 grams per hour, although some of the best models achieve emissions of 1.5 to 3 grams per hour.

What good is all of this mass?

Mass absorbs heat produced in the combustion chamber and slowly radiates it into the neighboring rooms. In fact, a masonry stove will release heat from a single load of wood for 6 to 24 hours, depending on the mass of the stove. Let me repeat: a single load of wood (40 pounds, or two armfuls) will heat a room or a small, open house for 6 to 24 hours!

Mass is not all that’s required to make this happen. Masonry heaters are also designed so that hot combustion gases escape through a labyrinth flue system within the mass, as shown in Figure 6-11. In this design, hot gases from the firebox are directed downward through the mass into channels usually on both sides of the combustion chamber. As the gases flow through these channels, heat is absorbed by the masonry material. The heat slowly migrates through this mass, eventually reaching the surface of the stove. In a wood stove, hot gases escape straight up the flue pipe.

Unlike a wood stove, the surface temperatures of which reach 500°–700°F (260°–370°C), the surface temperature of a masonry heater is 155°–175°F (68°–80°C). The brick radiates heat slowly into the room, creating long-lasting comfort with very little fuel. As the folks at Temp-Cast, a leading manufacturer of masonry heaters note, the masonry heater is “cherished for its gentle heating nature.”

Masonry heaters wring lots of heat from wood by virtue of their super-efficient combustion chambers. They trap that heat in their mass, then slowly release it into the room, providing long-lasting heat. Another secret of the exceptional performance of a masonry heater lies in the way it heats rooms through its release of radiant energy. That is to say, the heat given off by the stove radiates from its surface outward, like heat from the glowing embers of a fire, warming the walls, floors, furniture, pets, and people. All solid objects and living beings in the vicinity are heated.

Should You Consider a Masonry Heater?

Masonry heaters are ideal for new home construction, but not so good for retrofitting. As noted earlier, masonry heaters weigh considerably more than wood stoves — an awful lot more! Bill Eckert, who once sold masonry heaters in Colorado, noted that his Temp-Cast stove kits weighed 2,800 pounds. When facing was added, the finished stoves ranged from 4,000 to 8,000 pounds — 2 to 4 tons. So, in order to retrofit a home, you would very likely need to fortify the floor to support the mass of the stove. For models placed on wood floors, for instance, you would need to install additional floor joists — maybe even steel beams — and very likely even additional support posts in underlying rooms. Of course, beefing up the framing will require the expertise of a structural engineer and the efforts of a skilled framer. Both add to the cost of a retrofit.

If you are installing a masonry heater on a concrete floor, you will very likely have to dig it up and pour a deeper slab to support the weight of the heater. Most concrete floors aren’t strong enough to support a masonry heater.

For these reasons, very few masonry heaters are installed in existing homes. Most are installed in new homes designed specifically to accommodate the mass.

What’s in a Name?

Masonry stoves or masonry heaters go by several different names, reflecting either the origin of their design or the type of stove. Those of Russian origin are often called Russian fireplaces or Russian stoves. Swedish masonry stoves are … you guessed it … called Swedish stoves. Those originally made in Finland are Finnish stoves. Some lighter-weight units are known as tile stoves because of the use of decorative tile as a facing material. Austrian, German, and Swiss tile stoves can be quite ornate.

— Dan Chiras, The Solar House

How Big a Stove Do You Need?

As a general rule, the colder the climate, the greater the stove’s mass needs to be. The reason for this is that the more thermal mass a stove has, the longer it will heat. In extremely cold climates, five-ton stoves are common. In warmer climates, lower-mass models work well.

Those interested in masonry heaters can learn more about them and view some of their options by visiting the Masonry Heater Association’s web page, mha-net. org. Be sure to check out their photo gallery; it showcases a variety of beautiful masonry heaters from different installers. While you are visiting this site, check out the various dealers’ websites for photos of custom-made masonry stoves and kits.

Operating a Masonry Heater

Most masonry stoves are fired once or twice a day, using 35 to 50 pounds of wood, depending on the stove design, for each firing. Because there’s a lag time between the time you start a fire in the stove and the time the heat reaches the surface of the stove, masonry stoves are not considered a fast source of heat. Hence, operators must anticipate their heat demand and plan accordingly. Firing mid-to-late afternoon, for example, will begin to provide heat for a family within a few hours, depending on the mass of the stove, and will keep a house warm throughout the night and into the next day.

Can You Install a Masonry Heater Yourself?

Homeowners can purchase and install masonry heaters themselves, but it’s not a route I recommend. Masonry stoves require considerable knowledge of masonry materials and considerable expertise. Most stoves are built by skilled masons with years of experience in masonry stove construction. (To learn more about masonry heaters, I highly recommend David Lyle’s book, The Book of Masonry Stoves. Kate Mink has also published an excellent article on masonry heaters titled “Living with a Masonry Stove,” in Home Power, Issue 103.)

Pros and Cons of Masonry Stoves

As you can probably tell, I’m a big fan of masonry heaters. That said, I do recognize that they have some negatives. Let’s take a look at both the pros and cons so you enter this adventure with eyes wide open.

To begin, as noted above, masonry heaters are efficient and clean-burning. The heat is then radiated into the house over a long period, providing hours of comfort from a relatively small amount of wood. In addition, because masonry stoves burn cleanly, creosote buildup in their chimneys is not a problem, nor are creosote fires.

Masonry stoves are also pretty attractive. Facings of brick, stone, adobe, tile, or stucco give them a distinctive look. In fact, masonry heaters can be blended very nicely with almost any architectural style and decor. There aren’t many heating systems that you’d want to prominently display in your living room. This is one of them.

Many masonry stoves can be constructed with built-in bread or pizza ovens, so you can bake in them at the same time you are heating your home. Glass doors can also be installed so you can watch the fire. Note also that some designers build stoves that also heat water for radiant floor heat and hot water for showers and other domestic uses.

Masonry stoves require very little maintenance. An annual chimney cleaning is advised, although this is very likely a waste of time, or so say the experts. Creosote should never be a problem — unless the stove was improperly designed or built, or the user isn’t operating it correctly. The most common mistake occurs when users build small, smoldering fires instead of hot, intense ones. Smoldering fires produce a lot of smoke, as do fires that burn green wood. Inefficient combustion, in turn, leads to creosote buildup. If you want less heat, build a small, hot fire that burns fewer minutes.

Building Your Own Masonry Heater

You may be tempted to build your own masonry heater. Although this is possible, as noted in this chapter, it takes a lot of skill. Stoves need to be airtight, and the materials must be capable of withstanding extremely high combustion temperatures. Perhaps even more importantly, masonry heaters need to be built to accommodate the expansion and contraction of the mass as it heats and cools. An owner-builder is unlikely to have the kind of skill and expertise to pull this off. Only the most experienced stone masons should be hired, and even then only those with experience building masonry heaters. When facing material such as tile or brick is installed, it must be spaced properly so it doesn’t crack as the stove expands and contracts. Temp-Cast masonry heaters incorporate a “floating firebox” in their products. It isolates the heater core from the external masonry facing, which prevents the expansion and contraction of the firebox from damaging the facing. If not built correctly, or not built from the right materials, severe cracking can occur, leading to the collapse of the heater.

As also noted earlier, masonry stoves require additional framing of wood floors and additional reinforcement of concrete slabs, which add to the cost of new construction and make it difficult to add a masonry heater to an existing home. In airtight homes, make-up air needs to be supplied to masonry stoves. This also makes it difficult to retrofit a home for a masonry stove. And it adds some expense when building a new home.

Small amounts of fly ash may need to be removed periodically from the masonry flues. Accordingly, a masonry stove should have a clean-out that permits access to the smoke channels.

On the downside, masonry heaters are not widely available. To find a dealer near you, contact the Masonry Heater Association of North America’s web page listed above, or ask around for a dealer. A local wood stove retailer may be able to help you out. They may even sell masonry heater kits that they can install for you.

Like wood stoves, masonry heaters aren’t generally controlled automatically. Thus, they don’t provide heat when you are away from your home for any length of time, although some models can be equipped with a thermostatically controlled natural gas burner for such times.

Masonry stoves are not cheap, either. Building a masonry heater yourself could cost $5,000 or more. If you have a professional install one, expect to pay $6,000 to $15,000, give or take a little, depending on the size of the stove and the options you select, for example, a built-in pizza oven.

In closing, although it may seem out of step with the times to heat a house with a 16th-century wood-burning technology, don’t forget that we descend from many generations of people who heated their homes with wood.

Wood is a renewable resource — one we can count on from year to year if we manage our forests sustainably. And, as I like to remind audiences, many old ways of doing things are still the best ways.