SOLAR ELECTRICITY

POWERING YOUR HOME WITH SOLAR ENERGY

Solar electric systems are becoming extremely popular in the United States and other developed countries (Germany and Japan, in particular). The recent surge in their popularity is due to several factors, among them financial incentives and forward-thinking political policies designed to create a sustainable energy future.

Solar electricity is surprisingly popular in less developed countries. Although solar electricity is one of the most expensive sources of electricity known to humankind, in rural areas in less developed countries, it’s often much cheaper to install solar electric systems in small villages than to string miles of electric lines from central power plants to remote areas.

Solar electricity is also much cheaper than conventional electricity in certain applications in more developed countries. One example is the remote emergency solar-powered call box, a technology that is popping up along highways all across the United States (Figure 1-7). We’re even seeing them in cross-walk, where they power lights that help you safely cross the street (Figure 8-1). Why? It is far cheaper to provide solar electricity to these remote installations than to run an electric line to them.

Solar’s rural benefit is also evidenced by remote highway warning lights. Flashing lights on a remote Missouri highway, for example, warn drivers of a dangerous intersection (Figure 1-6). Solar electric lights are also found on buoys in major rivers, like the St. Lawrence River.

Solar electricity is often much cheaper than conventional power when building a home more than a couple of tenths of a mile away from an electric line — especially if the home is energy efficient. Although some local utilities have generous line-extension policies, many charge $20,000 or so to run a line a few tenths of a mile — and upwards of $50,000 to run a line a half mile. That $50,000 investment in electric poles and electric wire to hook up your home to the grid could be used to purchase a large solar electric system, possibly one even double the size of what an energy-efficient family would need (especially after subtracting financial incentives). One of my students once spent $60,000 to run electric lines to power two tiny cabins on land she owned in southern Colorado. She was surprised to learn that a $10,000 solar electric system would have sufficed.

Fig. 8-1: Solar cross-walk lights at Kansas State University in Manhattan, Kansas. The tiny PV module that powers the lights is located on the upper right. You’re looking at the back of the module in this photo.

Bear in mind that the fee a utility charges to connect a home or business to their network doesn’t pay for a single penny’s worth of electricity. It just buys you utility poles, an electric line, a meter, and a connection to the grid. What is more, you may need to pay the connection fee upfront, although some utilities will amortize the cost of connection, adding $200 to your electric bill for the next 20 years. In contrast, a $25,000 to $50,000 investment in an off-grid solar electric system will provide you and your family a lifetime of electricity (although you will need to replace batteries every 7 to 15 years, depending on how well you care for them).

Solar Electric System Incentives

Solar electric systems can make sense in places where electrical costs are extremely high. In California, Hawaii, and Germany, for instance, conventionally produced electricity goes for premium prices.

Solar electric systems also often make economic sense when financial incentives are available to utility customers. Financial incentives come in several forms. The most common are federal tax credits and local utility rebates. Together, they can decrease the initial cost of a solar electricity system by about one half. US businesses can receive their federal tax credit almost immediately by filing for a grant from the US Treasury Department once the system is installed. There’s no need to wait for tax season. And businesses don’t even need to have a tax liability to qualify for a tax credit.

US businesses can benefit from an additional economic incentive: accelerated depreciation on federal income tax. This allows businesses to depreciate the cost of a solar electricity system in five year’s time, which effectively reduces the initial cost of the system by approximately 30 percent, depending on the business’s tax bracket.

In the United States, the US Department of Agriculture offers grants for renewable energy systems that cover 25 percent of cost of the system. These grants are available to businesses in rural areas (areas with a population under 50,000).

Generous incentives such as these dramatically reduce the initial cost of solar electric systems and the cost per kilowatt-hour of electricity they generate over their lifetime, often making the electricity cost competitive with conventional electricity.

States and utilities also provide incentives. The state of Illinois, for instance, currently offers generous incentives totaling about 50 percent of the cost of a solar electric system. New York State offers its residents a 25 percent tax credit. The state of Florida currently exempts solar electric systems from certain taxes, and some areas like Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley, home to the prosperous town of Aspen, offer zero-interest loans for homeowners who install solar electric systems. A number of states, including Colorado and Missouri, require investor-owned utilities (IOUs) to provide rebates to customers who install solar electric systems. The rebates are frequently about $2 per watt of installed capacity (discussed shortly). To put this in perspective, it typically costs about $6 to $8 per watt to install a grid-connected system.

And there is more good news. In 2009, the price of solar electric modules tumbled and has remained low. (They’ve never been cheaper.) Thus, if you live in a state like Arizona, Illinois, New York, Colorado, or New Jersey, or are served by a utility that offers generous financial incentives, you may want to retrofit your home or business right now. If you own a business, especially one in a rural area, you can acquire additional benefits like a USDA grant for 25 percent of the system cost.

To determine whether you are qualified to receive a rebate, call your local utility. Better yet, check out incentives on the Database for State Incentives for Renewable Energy (dsireusa.org).

If there aren’t any incentives available in your area, you can still consider installing a solar electric system as a hedge against rising prices. Or you may, like me, want to install a system to achieve energy independence and reduce your environmental impact. Because solar electric systems can be expanded, you can invest in a few modules at a time and build your system over a period of five to ten years. For more on financing a renewable energy system, see Allan Sindelar and Phil Campbell-Graves’s article on the subject in Home Power magazine, Issue 103.

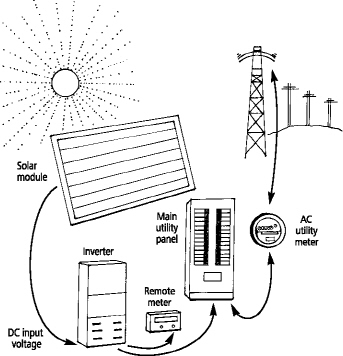

Fig. 8-2: Simplified anatomy of a grid-connected solar electric system.

WHAT IS A SOLAR ELECTRIC SYSTEM?

Solar electric systems fit into three main categories: grid-connected, grid-connected with battery backup, and off-grid. The differences will become clear shortly. Figures 8.6 to 8.8 show the three options and their main components.

Grid-Connected PV Systems

Grid-connected solar electric systems are the simplest of the three options. As shown in Figure 8-2, they consist of three main parts: solar modules, an inverter, and the main service panel or breaker box. Let’s begin with the solar array.

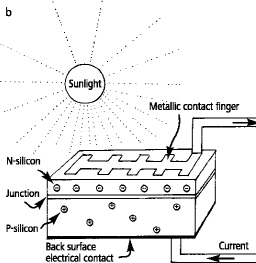

Like all other solar systems, the grid-connected solar electric system consists of one or more solar electric modules also known as photovoltaic or PV modules. (“Photo” refers to light, and “voltaic” means electricity.) Each solar module consists of numerous smaller solar cells, usually round, square, or rectangular cells that are about 1/100th of an inch thick and made from silicon (Figure 8-3a). Silicon comes from two highly ubiquitous materials, high-grade sand and quartz rock — both of which are made of silicon dioxide. Silicon is extracted from these materials to produce polysilicon.

Fig. 8-3: (a) Two solar cells. (b) Note that solar cells consist of two layers. Light striking the layers liberates electrons from the silicon atoms. These atoms flow from the deeper layer to the more superficial layer and then are drawn off by the metal contacts on the surface, creating direct current electricity.

The solar cells most widely used today consist of two thin layers of silicon. As illustrated in Figure 8-3b, each cell in a module has numerous thin metal electrical connections (metal contacts) on the surface that gather up electricity generated by the cell.

A solar or photovoltaic cell is a solid-state device that absorbs visible light and converts its energy to electricity. How a PV cell works is fascinating, but beyond the scope of this book. Suffice it to say that when sunlight strikes a PV cell, it liberates electrons from silicon atoms. Thanks to some ingenious chemistry (boron and phosphorus are added to different layers of the PV cell), these electrons are forced to migrate to the surface of the cell, where they are drawn away by the metal contacts on the cell’s surface, as shown in Figure 8-3b. Flowing electrons form an electrical current.

Because silicon reflects about 35 percent of the light striking it, the cells are coated with a thin, anti-reflective layer of silicon monoxide or titanium dioxide. The back of the cell consists of a thin layer of metal that completes the electrical circuit, as shown in Figure 8-3b.

Silicon cells are mounted in an aluminum frame, the module casing, and wired in series to boost the voltage. (Wiring in series increases the voltage.) The unit is sealed by a clear layer of glass, which prevents moisture from reaching the cells and also resists the pounding force of hail stones. (The glass in PV modules can withstand the force generated by a ball bearing striking it at 120 miles per hour.) Typical modules produce between 40 and 250 watts of electrical power under peak sunlight conditions. In most new systems, installers install 175 to 250-watt modules. Some manufacturers are producing even larger modules that produce around 300 watts.

Numerous modules are wired together to form a solar array. The array includes the modules plus a rack on which the modules are mounted.

PV modules can be mounted on buildings or on the ground. In urban and suburban areas, they are typically mounted on a durable metal rack on the roofs of homes. In rural areas, PV modules are mounted on roofs or on the ground. Whatever location you choose, be sure it has full access to the sun year round for optimal performance.

In some installations, the modules are mounted on a rack attached to a pole. Some pole-mounted systems include a tracking device that enables the array to follow the sun from sunrise to sunset each day. These are known as single-axis trackers. Other, more elaborate trackers follow the sun from sunrise to sunset, and also adjust the tilt angle of the array to accommodate the change in the sun’s angle. (The sun is higher in the sky in the middle of the day and in the summer.) These are known as dual-axis trackers. (Be sure to install your solar electric modules so they are out of the reach of vandals or livestock.)

Tracking arrays boost the output of a PV system by 10 to 40 percent. For best performance, a tracking array should be located in an open field or large, open (treeless) lawn that permits access to the sun from sunrise to sunset. Trackers perform better in northern regions because they experience longer days in the summer. Dual-axis trackers perform only slightly better than single-axis trackers.

Trackers add to the cost of a PV system, but the higher cost can be offset by the value of the electricity produced. Because trackers have controls, motors and other moving parts, they may require periodic repair or replacement of damaged parts, such as the controller that runs the motors. Because of this, you may be better off adding a few more solar modules to a fixed array (one that doesn’t track the sun) rather than installing a tracker. Be sure to consider the cost of a tracker and how it affects the cost per kilowatt-hour of electricity the array will produce.

Solar modules produce direct current (DC) electricity when the cells are struck by sunlight. Direct current electricity consists of electrons flowing in wires in a single, fixed direction. The energy they contain can be used to power motors, lights, home appliances, and a host of other electronic devices.

The DC electricity produced by a solar array is carried away by wires that lead into the home. As you may know, however, virtually all of our homes use another type of electricity, known as alternating current (AC). AC electricity consists of electrons that cycle very rapidly back and forth through a wire. In North America, standard household current is 60 hertz, or 60 cycles per second. That means that in standard household electrical current, the electrons cycle back and forth 60 times per second. The energy these electrons carry is used to power a wide range of 120- and 240-volt appliances and electronic devices in our homes and businesses.

In order for the DC current produced by PV cells to power our homes, then, it must be converted into AC current. This task is relegated to an inverter, shown in Figure 8-4. The inverter converts DC electricity into AC electricity. Inverters also change the voltage of the incoming DC electricity to 120 volts or 240 volts (needed for some appliances, like electric clothes dryers). Inverters are generally located near the main panel or breaker box.

Fig. 8-4: This quiet, efficient inverter by Sunny Boy converts direct current produced by PVs (or a wind generator) into alternating current and boosts the voltage to 120. Inverters that are used in systems with batteries typically contain battery chargers.

Fig. 8-5: The Enphase microinverter. This inverter is mounted on the rack behind each module. Modules plug into the inverter, which produces 240-volt alternating current electricity.

In recent years, Enphase has introduced a promising new product known as the microinverter (Figure 8-5). Interestingly, microinverters are attached to each module in a PV array. They are only used in grid-connected systems. While traditional inverters produce either 120-volt or 240-volt AC current that travels to the main electrical service box of your home, microinverters produce 240-volt AC electricity.

AC Devices Run on DC

Even though we plug all electronic devices and appliances into wall sockets that deliver alternating current, many of them actually run on DC current. The small black transformer of a laptop computer, for instance, converts the AC to DC and decreases the voltage. Even TVs and stereo equipment convert incoming AC to DC.

They are wired directly into the main panel via a circuit breaker.

The breaker box contains electrical circuits, known as branch circuits, that supply various parts of a home or business. It also contains circuit breakers to protect the wires in a home or business from overcurrent — carrying more electricity than they are rated to carry. Overcurrent can cause wires to heat up and start a fire.

In grid-connected systems, electricity from the solar array powers electronic devices in our homes and businesses. Surplus electricity is automatically sent into the electrical grid (Figure 8-6a). Surplus power simply flows out through the main service panel through the utility meter. It then flows through the electrical wires that connect to the local utility network. These are the wires that connect homes and businesses to regional power plants; they are often referred to as the “electrical grid.” (Technically, the electrical grid consists of the high-voltage electric lines that crisscross countries. The local electric lines are the utility network.) The surplus sent to the electrical grid is consumed by your neighbors.

In many grid-connected solar electric systems, electricity flowing to the grid runs through the same meter that keeps track of electricity delivered to your home from the grid. Electricity you are sending to the grid, however, runs the meter backwards, so you are credited for the electricity you are supplying to the grid. (More on this shortly.) In other systems, electricity flows through a separate meter that keeps track of how much electricity you supply to the grid. Utility meters are fairly large, tamper-proof glass-encased meters installed by the utility company. They keep track of monthly energy production and consumption so the utility can bill you at the end of each month.

Additional Components: Meters and Disconnects

All code-compliant solar systems include two additional components: meters and various disconnect switches. Meters are typically located on the inverter and are used to measure electrical production by a PV system. They’ll tell you how much electricity the PV system is producing and other important information.

Meters typically give readings on the watts, amps, and volts of incoming DC electricity and the same for outgoing AC — AC produced by the inverter. They keep track of daily production and long-term production in kilowatt-hours. (Which is how we know that in its first year, The Evergreen Institute’s 5-kW PV system produced over 6,200 kilowatt-hours of electricity!). If an inverter doesn’t come with a built-in meter, you can buy a separate unit and connect it to your system, and it will provide the data.

Grid-connected solar electric systems also contain a couple of safety switches, called disconnects. Disconnects enable homeowners or service personnel to shut power down to prevent electrical shock when working on the system.

As shown in Figure 8-6b, a DC disconnect is located between the solar array and the inverter. It is used to terminate the flow of electricity to the inverter. Today, modern inverters have a DC disconnect built into them, so it is not always necessary to install a separate DC disconnect.

The other disconnect, the utility-accessible AC disconnect, is located between the inverter and the main service panel. It is used to shut off the flow of electricity from the inverter to the household circuits and the grid. Utility workers use the AC disconnect to shut off the system if the lines go down and they need to work on the electric lines to your home or in the neighborhood. However, because inverters shut off automatically when they sense that the grid is down, an AC disconnect is not really needed; your utility may recognize this and not require you to have one.

How Utilities Meter Electricity in Grid-Connected Systems

Unlike off-grid systems, grid-connected PV systems have no physical on-site electrical storage capacity. That is, they have no means of storing electricity for later use, for example, at night when the PV modules are inactive. Solar homeowners, however, use the electrical grid as their “storage battery.” That is to say, the electrical grid accepts excess electricity when a solar electric system is producing more electricity than a home is using. Excess electricity that’s transferred onto the grid is used by one’s neighbors. However, at night, when a system is no longer producing electricity — or during the day when a home requires more electricity than the PV system is producing — electricity is drawn from the grid.

To keep track of this, many utilities simplify matters by installing one electrical meter. Older meters contain a flat disk that runs forward when electricity is being drawn from the grid. Each rotation of the disk represents a certain amount of electricity consumed by a household. Rotations of the disk are converted to kilowatt-hours by the meter.

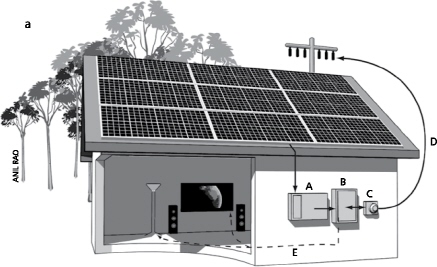

A Inverter

B Breaker box (main service panel)

C Utility meter

D Wire to utility line

E Circuits to household loads

Fig. 8-6: (a) This schematic shows the major components of a grid-connected solar electric system and illustrates how surplus electricity is backfed onto the electric grid. (b) This diagram shows more detail, including charge controllers and disconnects.

When electricity is flowing on to the grid, the meter runs backwards, subtracting from the amount of electricity your home has consumed previously. The kilowatt-hour reading on the meter decreases.

All utilities in the United States are required by federal law to accept electricity from small generators. Most are required by state law to engage in net metering. In very basic terms, what net metering means is that every bit of electricity you feed onto the electric grid can be withdrawn at no charge during the billing cycle.

Two types of net metering are in place in the United States: monthly and annual. If you are on a monthly net metering plan, surpluses generated during the day can be withdrawn from the grid whenever they are needed, at no charge. If you are on an annual net metering plan, these surpluses can be carried from one month to the next. So, if a PV system generates a surplus in September, it can be used in October or even November or December. Annual net metering systems are a lot like cell phone plans that allow customers to roll minutes over from one month to the next for up to one year.

To see how these work, let’s start with a monthly net metering plan. Suppose your system delivered 400 kilowatt-hours of electricity to the grid but your household consumed 400 kilowatt-hours at night and at other times. If this were the case, your cost for electricity would be zero — although utilities usually charge you a fee (around $10–$20 per month) to read the meter.

If your PV system produced 200 kilowatt-hours less than you consumed, you would be charged for the consumption. But what would happen if your system produced a surplus during the monthly billing cycle — say 400 kilowatt-hours more electricity than you withdrew from the grid? This is called net excess generation.

Most states in the United States now have net metering laws that dictate how utilities must deal with surpluses. Basically, there are three options. First, utilities can be granted the surplus. That is, they take your 400 kWh, sell it, and made a nice profit. Second, they can be required to pay you their avoided cost, that is, what it costs the utility to buy or generate electricity. Avoided cost, or wholesale rate, is typically about one fourth of the retail rate. If the utility is selling electricity to its customers for 10 cents per kWh, the avoided cost is typically about 2.5 to 3 cents per kWh. So, if your system produced 400 kWh of surplus, you’d receive a check or, more likely, be credited on your bill for the 400 kWh at 2.5 to 3 cents per kWh. In other words, you’d be paid or receive a deduction from your bill (e.g., monthly service charge) of $10 for the $40 worth of electricity you delivered to the grid (which they sold for 10 cents per kWh).

More on Net Metering

To view some frequently asked questions on net metering, you can visit the website sponsored by Home Power magazine, a leader in home renewable energy: homepower.com.

The third option is that the utility is required to reimburse customers for net excess generation at the retail rate—the amount they charge their customers. This is, of course, the best deal.

In states with annual net metering, surpluses generated in sunnier months accumulate and can be used in less sunny periods. At the end of the one-year period, the utility may keep the surplus, pay for it at avoided cost, pay for it at retail rates, or continue to roll over excesses into ensuing years — it all depends on state law. Kentucky allows surpluses to be carried indefinitely. In Colorado, customers of investor-owned utilities can opt for indefinite rollover.

As you study this issue, you will find that there are three types of utilities: (1) large, investor-owned utilities that typically serve urban areas; (2) municipal utilities, that is, power companies owned by cities and towns; and (3) rural cooperatives, nonprofit organizations that typically buy electricity from various producers and then sell it to their rural customers. Different rules apply to each of them. For instance, in Colorado, investor-owned utilities are required to pay customers wholesale rates at the end of the year, but rural co-ops and municipal utilities — called “munis” — can pay whatever they deem reasonable. Unfortunately, many rural cooperatives have been antagonistic toward solar and wind systems, and may not be easy to work with. However, I’ve worked with two rural cooperatives in Missouri and found them both to be very cooperative.

Does Your State Net Meter?

To see if your state offers net metering and to learn the specifics of your state’s program, visit the US DOE’s website at eere.energy.gov/ and search for “net metering.”

As of September 2010, 43 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia had mandatory net metering laws in place. Texas and Idaho initiated voluntary programs. South Dakota, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama have none. See the sidebar, “Does Your State Net Meter?” for a website that will help you determine the policy in your state.

Grid-Connected Systems with Battery Backup

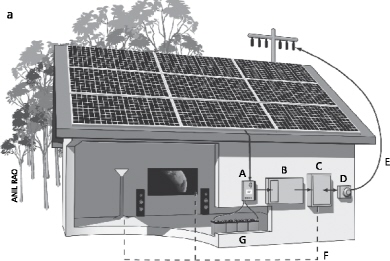

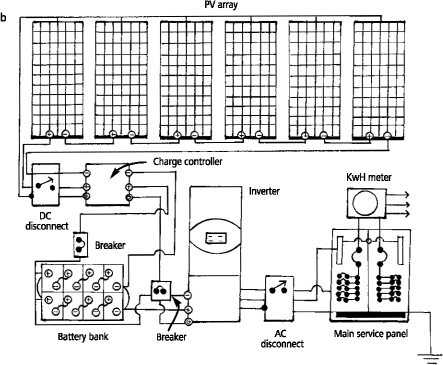

Some homeowners elect to install batteries in their grid-connected systems to provide backup power in case grid power goes down (for example, if a tree branch falls on a utility line and shuts down the electrical power system supplying you and 65 million other people). A typical grid-connected system with batteries is shown in Figures 8-7a and b.

A Charge controller

B Inverter

C Breaker box (main service panel)

D Utility meter

E Wire to utility service

F Circuits to household loads

G Back up battery bank

Fig. 8-7: (a) This schematic shows the major components of a grid-connected solar electric system with a battery bank to store backup electricity. (b) This diagram shows more details, including controllers and disconnects whose functions are explained in the text.

In grid-connected systems equipped with batteries, the solar array produces electricity that keeps the batteries fully charged at all times. Solar electricity also feeds live circuits in the house during the day. When the batteries are full and all demand is met inside a home or business, excess electricity is backfed onto the electrical grid. At night, power required for household use is delivered by the grid. The grid also supplies electricity when demand in a home or business exceeds the output of the PV array. The batteries are called into action only when grid power fails, although a homeowner can switch to battery operation if desired via a manual transfer switch.

A grid-connected system with battery backup includes all of the components of a grid-connected system, including disconnects for safety. Grid-connected solar electric systems with battery backup, however, also require a couple of additional components, including the batteries, and a component we haven’t discussed yet — the charge controller — as shown in the schematic in Figure 8-7b.

Charge controllers are devices that regulate the charging of the batteries during normal operation and during times when the PV system goes off grid — for example, when the electric utility experiences a blackout and the system switches to battery power. Charge controllers not only regulate battery charging, they protect batteries from overcharging (how they do this is beyond the scope of this book). Overcharging can damage the lead plates inside batteries, reducing battery life. (If you want to learn more, check out my book, Power from the Sun.) The charge controller is housed in a metal box that is mounted on the wall near the inverter and the batteries.

Grid-connected systems with battery backup also contain meters to monitor electrical production, battery voltage, and battery storage — how much electricity is stored in the batteries. Some meters are on the charge controller and others are on the inverter.

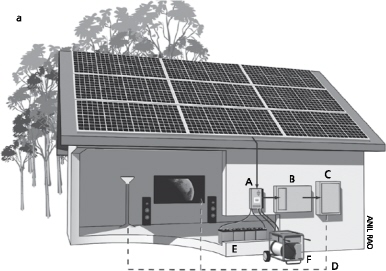

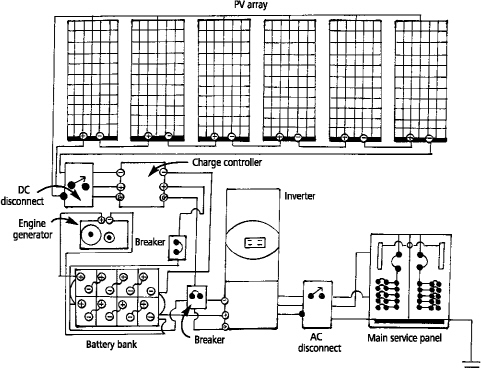

Off-Grid (Stand-Alone) Systems

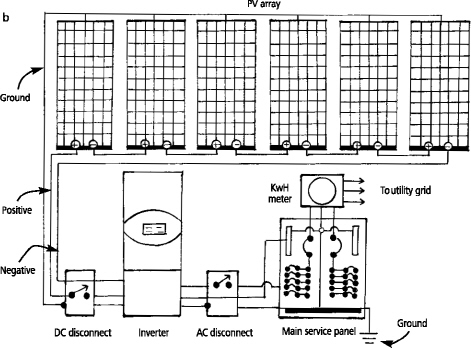

Next on the list is the off-grid system, also known as a stand-alone system. Figures 8-8a and b show the anatomy of an off-grid solar electric system. As you can see, it is very similar to the grid-connected system with battery backup. You will notice two distinct differences, however. First, there is no connection to the grid. Thus, no surplus electricity can be backfed onto the grid. This system produces electricity that meets immediate demand but also stores electricity in batteries for use at night or during long, cloudy periods. The batteries also supply electricity when the immediate demand exceeds the output of the PV array. Second, this system usually includes a backup generator that can be run to charge the batteries when they run low. Some people install wind turbines to serve as a second charging source.

A Charge controller

B Inverter

C Breaker box

D Circuits to household loads

E Battery bank

F Back up generator

Fig. 8-8: These schematics shows all the components of an off-grid solar electric system, including charge controllers and disconnects.

As illustrated in Figure 8-8, the main power source of an off-grid system is the PV array. Electricity flowing from the array into the house first travels to the charge controller. It can then travel to the batteries and to the inverter, where it is converted to AC electricity. At night, all electricity required in an off-grid home comes from the batteries via the inverter, which converts the low-voltage DC solar electricity to high-voltage AC current. (Batteries are typically wired at 12, 24, or 48 volts, depending on the electrical demand of a home.) The electricity is then delivered to open (active) circuits in the house via the main panel, a.k.a. the breaker box.

What happens if the batteries are full?

In off-grid systems, the charge controller terminates the flow of electricity from the PV array to the batteries when they are full. This prevents the batteries from overcharging. This task is managed by the high-voltage disconnect in the charge controller.

Like other solar electric systems, off-grid systems require an AC and DC disconnect to enable a repairman to service a system without being electrocuted.

Off-grid solar electric systems like the one shown in Figure 8-8 also include a low-voltage disconnect housed in the inverter. When it senses low battery voltage, it terminates the flow of electricity from the batteries to the inverter. This prevents over-discharging — that is, draining the batteries too low. Over-discharging can permanently damage a battery bank.

Power Centers

Off-grid solar electric systems can seem pretty complex; they have enough connections to frustrate the far more complex neuronal pathways in the human brain. There is, however, a way to avoid some of the confusion: install a power center (Figure 8-9).

A power center is the grand central station of off-grid and grid-connected systems with battery backup. Power centers contain the connection points to which the electrical wires from the charge controller, the inverter, the batteries, and the solar array all connect. The power center houses the circuit breakers that protect the wires and the disconnects that allow servicing.

I loved the Ananda power center in my off-grid home in Colorado. In the classroom building at The Evergreen Institute, my students and I installed an Outback (Flexware 500) power center for the grid-connected system with battery backup. Unfortunately, the Flexware 500 was not pre-wired and came with rather generic wiring diagrams. The frustration mounted as we started to wire the system, but faded quickly once an experienced installer in our area handed us a good wiring diagram. So, be sure to get a power center that is pre-wired — or ask for a wiring diagram that matches your application. I strongly recommend that you consider a power center if you are going to install a PV system with batteries. It will cost a bit more than buying the components separately, but it is well worth it when you factor in the massive reduction in cerebral hemorrhaging that will result from attempts to buy all of the components separately and wire them in some meaningful and functional manner (that meets all of the safety requirements of the National Electrical Code).

Fig. 8-9: For stand-alone systems, the power center is a helpful organizer of components. It contains meters, charge controllers, and disconnects.

Another good reason to consider buying a power center is that they are very popular among electrical inspectors — who typically know very little about solar electric systems and are often totally confused by battery-based PV systems. When an inspector sees a power center, he or she knows that all of the essential safety circuitry and all of the vital components required in a solar electric system are present and accounted for, housed in a single assembly. Rather than have to go through the system with a fine-toothed comb, they’ll take one look at your system, find the UL (Underwriter’s Laboratory) sticker, and then check it off on their inspection sheet and move on to their next inspection.

DC Circuits

So far, the discussion of solar electric systems has focused on converting the DC power they produce into the AC power used in our homes. Solar electric systems can also be designed to use DC power directly — for all circuits, or just a few. In my home in Colorado, for instance, I ran a small, 24-volt DC electric pump to pump water from my cistern to the house. I did this for one simple reason: to bypass the inverter. By doing this, I save energy and simplify the system.

How does bypassing the inverter save energy?

Inverters consume energy when they’re operating. For example, when my inverter converts 24-volt DC electricity from my batteries to 120-volt AC current, it loses about 10 percent of the energy that goes through it. By bypassing the inverter with a DC circuit directly to the water pump, I raise the efficiency of my system.

Other appliances and consumer electronics can also be run on DC power. For example, SunFrost refrigerators, which are one of the most efficient refrigerators on the market today, can be ordered with DC components at no extra cost. Because refrigerators account for about 8 percent of a family’s daily electrical consumption, you can save substantially by purchasing a DC refrigerator and bypassing the inverter.

Ceiling fans can also be ordered in DC models. Here, though, you need to think carefully. I was planning on doing this until I found out (in 1995) that DC ceiling fans cost $200 each, compared to $40 each for standard AC ceiling fans. I couldn’t justify spending $480 more for three ceiling fans to bypass the inverter. Many other DC appliances are available, but they tend to cost more and are typically designed for use in RVs or cabins. They’re not ideal for household use, unless you’ve pared down your demands. They also tend not to stand up to daily use very well. Low-voltage DC electricity doesn’t travel very efficiently through small wires, so large and more expensive wires are required, which adds to the cost. DC wiring requires special, more costly receptacles. All in all, the electricity you save by bypassing the inverter may be lost by transmitting low-voltage DC through your home. As a rule, then, DC circuits aren’t of much value in most homes. But don’t close the book on them. You may want to install at least one DC circuit to power a lightbulb in the utility room (where the inverter is located) in case of emergency.

System and Battery Maintenance

Before you make up your mind what kind of solar system you want, you should consider system maintenance. A grid-connected system is virtually maintenance-free. If you live in a dry dusty area or a polluted city, you may need to periodically wipe, rinse, or dust off your PV modules from time to time. In most locations, however, rain does the job free of charge. (I’ve never cleaned mine in Colorado, and we only get about 20 inches of precipitation per year. I’ve also never cleaned my PV modules in Missouri, where it rains a lot.)

In snowy climates, you may need to sweep snow off your array, being careful not to damage the modules. Even a tiny amount of snow blocking the lower edges of PV modules in an array can reduce production by more than 90 percent. (When snow melts on an array, it tends to slide down and may accumulate along the bottom of the modules.) If you live in a snowy climate, be sure to install PVs within reach so you can remove snow easily.

Off-grid PV systems are more complicated than grid-connected systems and require a lot more maintenance. Why do I typically recommend against them? Because lead acid batteries used in off-grid systems require babying. Batteries function optimally at 70°F (21°C). At higher or lower temperatures, their performance plummets. To ensure optimal performance and long life, you need to house batteries at their preferred temperature — which means in a space where temperatures remain between 50 and 80°F year round. Many people house their batteries in sheds or in garages, often inside a sealed battery box. But take note: the battery room or battery box must be vented to the outside so that hydrogen gas produced when batteries are charging can be safely vented outdoors. (Hydrogen is explosive at certain concentrations.) Remember to include these costs in your calculations; building a safe battery box and outfitting a place to keep it costs money.

Battery Room Safety Equipment

A battery room should be equipped with a smoke detector, an appropriate fire extinguisher, and a case of baking soda to neutralize acid in case of a fire or spill. Rubber gloves and safety glasses are also essential for dealing with batteries.

Watering Your Batteries

Batteries naturally lose water when being charged, either by electricity from the PV modules or the generator. To keep the lead plates from drying out, which can ruin them, you need to periodically refill your batteries, one cell at a time, with distilled or de-ionized water. Batteries should be checked every month and topped off if necessary (be sure not to overfill), according to Richard Perez, who publishes Home Power magazine. Refilling takes a half hour or so, depending on the size of your battery bank and how accessible the batteries are.

Fig. 8-10: These Hydrocaps replace the standard caps that come with lead acid batteries. A catalyst in the reservoir captures hydrogen and oxygen given off by the breakdown of water and recombines them, reducing water loss by 90 percent, thus cutting down on routine maintenance.

Fig. 8-11: This battery filling system is designed for those who don’t want to have to top off their batteries every three or four months. Float valves in the caps tell when a cell needs replenishment. Distilled water flows into the cells from a central reservoir (not shown here).

To reduce water loss and battery maintenance, two companies have produced special battery caps: Hydrocaps and Water Miser caps. Both caps are designed to replace standard cell caps that come with lead acid batteries.

Hydrocaps contain a small catalyst-filled reservoir (Figure 8-10). The platinum catalyst converts the hydrogen and oxygen released by charging batteries into water (see sidebar, “Reducing Battery Maintenance,” for explanation). Hydrocaps reduce water losses by around 90 percent. (As noted in the sidebar, you can also install automatic and manual battery filling systems to reduce battery maintenance.)

Water Miser caps also reduce water loss, but only by 30 to 75 percent. They also function differently. Rather than trapping hydrogen and oxygen and converting it back to water, the Water Miser caps trap water vapor and the fine acid mist that evaporates from the battery fluid. The liquid water and acid then drip back into the batteries. Of the two, I prefer Hydrocaps. They cost more than Water Miser caps but do a better job at reducing water losses.

Another way to reduce maintenance is to install a battery filling system, shown in Figure 8-11. Battery filling systems automatically fill batteries from a central reservoir filled with distilled water, totally eliminating this time-consuming chore. Battery filling systems consist of a series of plastic tubes connected to a central reservoir in the battery room. Each battery cell is fitted with a special cap equipped with a float valve. When the water level drops in a cell (there are usually three cells per battery), the valve opens and allows water to fill the battery to the proper level. Unfortunately, the unit costs about $16 per cell or $48 per battery. A system for a battery bank with 12 batteries would cost about $575. Despite the cost, I installed one on my battery bank in Colorado and found that it reduced battery maintenance (filling) from 30 minutes to 5 minutes, making the investment well worth the money.

Equalizing Your Batteries

Batteries also need to be equalized from time to time — usually, every three or four months. Equalization is a controlled overcharge of the batteries.

Batteries are typically equalized by running an external gas-powered generator (commonly called a “gen-set”). The process is pretty simple: to equalize batteries, you start up the generator, which is connected to a battery charger located in the inverter. Then you flip on the circuit breaker in the line connecting the generator to the inverter/battery charger. At this point, the inverter/battery charger takes over. When equalizing batteries, electricity is fed into the battery bank very rapidly at first. As the batteries are charged, however, the flow of electricity gradually slows. At the end of the process, electrical current trickles into the batteries. When the batteries are fully charged and equalized, the inverter shuts off, and you’re done.

Reducing Battery Maintenance

When batteries are being charged, electricity passing through water breaks it down into hydrogen and oxygen gases. Hydrogen and oxygen enter the catalyst-filled reservoir in the Hydrocap where they recombine to form water, that then drips back down into the battery. This not only reduces the need for you to add water, it also reduces the danger of hydrogen gas being emitted from battery banks.

Equalization achieves three important goals. It raises the voltage of each cell to the same level for optimal function, hence the name “equalization.” (A battery bank performs only as well as the lowest-voltage cell in the array.) Equalization also cleans the plates in your batteries by driving the lead sulfate off your plates. Lead sulfate forms on the lead plates of batteries when they discharge — that is, give off electricity. Lead sulfate accumulating on the plates inside a battery reduces the amount of electricity a battery can store, greatly hindering battery function. (For those who know a bit about batteries and lead acid battery chemistry: lead sulfate forms on the lead plates that feed into the anode [the negatively charged pole] as well as those that feed into the cathode [the positively charged pole]).

Periodic equalization also helps mix the sulfuric acid in which the lead plates are immersed. All in all, then, equalization helps restore batteries and increases their lifespan.

Are Batteries for You?

Battery-based systems have their advantages, but you should be aware of their disadvantages. They are costly. A single battery bank may contain one to two dozen batteries costing $200 to $300 each. The battery bank needs a home, as noted earlier, that is, some safe place where batteries can be kept warm but not hot. This costs money. And don’t forget that your battery bank needs to be wired into your solar electric system, which also requires a bit of money. In addition, batteries require all the periodic maintenance just described.

Optimistically, lead acid batteries only last five to ten years, according to Johnny Weiss, director of Solar Energy International, depending on how you take care of them, and how heavily you draw on them. Replacing batteries costs money.

Which System is Best for You?

You’ve got three choices in solar electric systems. You can install a grid-connected system, which is by far your cheapest and easiest option. When installing a grid-connected system in a brand new home, you’ll have to run electric lines to your home and install a utility meter or two to track electricity. In new and existing homes, you will also probably be required to install an AC disconnect, so fire fighters can shut your solar system off in case of a fire or utility company employees can shut off your system if they’re working on the lines in the neighborhood. They don’t want electricity flowing onto the grid from your system while they’re working on nearby lines for fear of electrocution.

In truth, AC disconnects are really unnecessary, so some building departments no longer require them. Departments that still insist on AC disconnects do not properly understand that all modern inverters (UL-1741 listed inverters) automatically terminate the flow of electricity from a solar electric system to the grid when they sense a drop in line voltage in the grid — either a blackout or brownout.

One serious disadvantage of a grid-connected system, however, is that when the grid goes down, so does your system. It can be the sunniest day of the year. It doesn’t matter. Your PV system will stop producing electricity so long as the inverter detects a blackout or brownout. Once these events are over, the inverter will turn back on automatically, and restart energy production.

Your second option is a grid-connected system with a battery bank. Or you can go off-grid entirely, by installing an off-grid system. When consulting with clients on system type, I typically suggest that clients start with a grid-connected PV system. Use the grid as your battery bank and suffer through sporadic power outages with the rest of us. If outages are frequent, long, a major inconvenience, or a health or safety issue, then a grid-connected system with battery backup might be a better way to go.

If you are installing a system on an existing home, be sure to contact the local utility company well in advance and ask for a copy of their interconnection agreement, which you must sign and submit along with system information, most notably a description of the system and the automatic disconnect feature. (As just noted, any inverter with a UL-1741 listing will comply with utility regulations for automatic disconnection. It’s called anti-islanding.) The form may require an installer’s signature, attesting that your system will be designed and installed according to the National Electric Code.

Be sure to apply for a building permit. You may need a permit that covers the structural aspects of the project — rack design and the ability of your roof to support an array — and you will probably need an electrical permit. In some parts of the country, like many counties in rural areas, no permits are needed. You are on your own. Nonetheless, you should be sure your system is properly installed for the safety of everyone involved.

If you are considering installing a solar electric system, you obviously have to think all of this through very carefully. To hold costs down, you might want to begin with a small, grid-connected system. Five 200-watt panels would give you a 1,000-watt system, which would cost around $6,000–$8,000 (including installation), depending on the type of module you buy and the difficulty of installation. Federal tax credits would trim 30 percent off the price tag. Other incentives could further reduce the cost.

A small grid-connected PV contains all the main components of a full-fledged solar electric system. That is, you’ve got all of the expensive hardware in place. You can add modules later as your finances permit, so long as you have sized your inverter properly. (I recommend oversizing the inverter initially to match possible future demand.) Be sure to install identical modules, too. You can even add a battery bank at a later date, if you want. Though you would need to install a new inverter. And you could eventually disconnect from the electrical grid entirely if you feel comfortable that an off-grid system will work for you.

Efficiency First!

If you decide you are going to join the growing legion of solar electric homeowners, the first thing you need to do is to make your home as efficient in its use of electricity as humanly possible. You’ll save a fortune on your solar electric system if you do. As a general rule of thumb, every dollar you invest in efficiency will save you $3 to $5 in system costs, before rebates. Thus, $1,000 invested in measures that cut electrical demand by 25–50 percent can save you $3,000 to $5,000 in system costs. Chapter 2 outlines efficiency measures that will help you reduce electrical demand. While you are at it, be sure to eliminate or reduce phantom (ghost) loads. Although individual phantom loads are small, remember that they’re on 24 hours a day. Many tiny loads in a house add up, and servicing them can add substantially to the cost of your system.

Making Sense of Generators

Off-grid systems typically require a generator for backup power, but generators are also needed for routine battery maintenance, notably periodic equalization. How often homeowners need to run a generator depends on many factors, among them the size of the PV system, household energy use, and the amount of available sunshine. Gas generators are fairly inexpensive, but they burn costly fossil fuels (gasoline). They’re also prone to break down, and many models are quite noisy. In addition, some units may not last more than 500 hours. Because of these factors, I recommend that homeowners oversize their solar electric systems — that is, that they install a larger PV array and a larger battery bank than they might ordinarily consider. This way, they won’t need to supply backup power so often. A larger battery bank means that batteries aren’t deeply discharged as often, which reduces the need for periodic equalization. Or, you may want to consider installing a wind system to make up for shortfalls that occur during cloudy periods.

Sizing a System

Sizing a solar electric system can be tricky, especially if you are installing a system on a house you’re just moving into or a house you are building. In such cases, how do you know how much electricity you’ll need?

What most people do is make a list of all the appliances and electronic devices that will be used in the house. Once this is complete, they estimate how long each appliance or device is used each day. They then multiply the power consumption (in watts) of each device. (Power consumption is listed on all electronic devices on a small plate or sticker on the back of the unit. Go check your microwave or TV right now.)

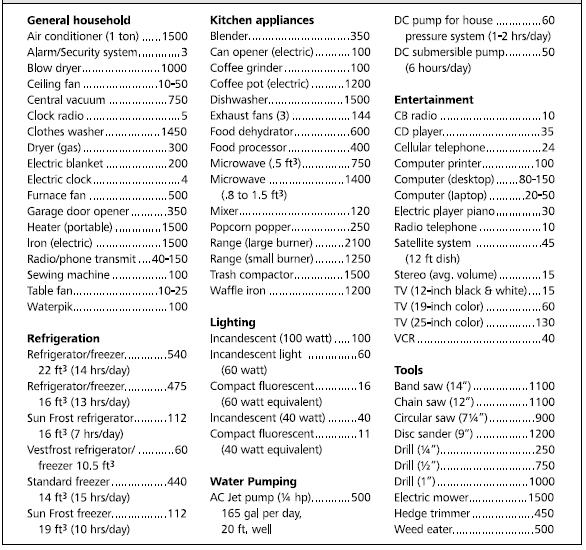

Another way to calculate usage is to consult a table that lists typical wattages of household appliances and electronic devices. Figure 8-12a shows a typical appliance wattage chart. It gives the electrical consumption for each device.

Multiplying wattage of each appliance by the estimated time it is used each day gives you the daily electrical consumption in watt-hours.

From this analysis, you should be able to calculate your total daily energy requirement in watt-hours. Note, however, that some appliances or electric devices may be used more during some parts of the year than others. Lights, for example, are on more often during the winter than the summer because the days are shorter in the winter. The television may run less frequently during the summer because the kids are outside playing. Try to take such differences into account when computing energy consumption (Figure 8-12b).

Once you know how much electricity you consume, you need to perform some additional calculations. These are typically in a worksheet form. You can also complete this process using computer software.

The worksheets available through Solar Energy International’s book Photovoltaics: Design and Installation Manual help you determine electric load (demand for electricity) as just described. You are then led through a few computations to determine the size of the inverter you’ll need. Once you know this, you can determine the size of the battery bank you’ll need if you are designing an off-grid home. The worksheets then lead you through calculations to size the array — that is, to determine the number of PV modules you’ll need. This calculation takes into account your demand, the efficiency of the entire system, and solar availability.

If your eyes are starting to glaze over, don’t despair. A local installer can run the numbers for you. Even if you are planning on installing the system yourself, consider hiring a local installer to consult with you at this stage. (Be careful, if you install a system yourself. You’ll be dealing with high-voltage DC and AC electricity that can be dangerous!)

Off-grid PV systems should be sized for the month with the highest energy demand. You can learn how to do this by taking a solar electricity course or by reading more advanced books on solar electricity. An installer will do the math for you, at no charge.

Grid-connected systems are sized for annual energy production. That is, you determine how much electricity you need annually. Once this is determined, you can size a system based on average daily use and the amount of sunshine in your region. Again, if your system is going to be installed by a professional, they’ll run the math.

In an existing home, it is easy to determine the amount of electricity you consume each year. But in a new home, you’ll need to make an educated guess.

Table 8-12a

Typical Wattage Requirements for Common Appliances

Fig. 8-12: Sizing a Solar Electric System. (a) This table provides typical wattage (power consumption) readings for major appliances and household electronics. (b) This worksheet can be used to list all of your appliances and to determine how much power they use each day.

But remember: reduce your demand first! Apply energy conservation measures vigorously before you estimate how much electricity you will be using.

Table 8-12b

Stand-Alone Electric Load Worksheet

BUYING A SOLAR ELECTRIC SYSTEM

When it comes to buying a solar system, many people wisely turn to a local PV dealer/installer who can select the components and ensure that all of them work well together. Although this option may cost a bit more than those I’ll explain shortly, it’s a good approach. A competent local installer can answer all of your questions and take care of problems that may arise. (Be sure they really know what they’re doing.) Unless you’re mechanically inclined and pretty knowledgeable, embarking on this process yourself can put you on a steep and treacherous uphill climb. “Even licensed electricians often need help from experienced PV installers,” notes Weiss. You can find a list of local installers at homepower.com or at findsolar.com. Also, be sure to check out the local business directory your phone company provides.

Another approach is to buy a system from an Internet supplier. This approach can save you a substantial amount of money, as deep discounts are available through the Internet. Once the system arrives, though, you will have to install it yourself, or try to hire a local installer to do it for you. However, local installers may not be happy that you cut them out of the first part of the deal. (They make a little profit on the sale of equipment.) If you do buy through an Internet supplier, you’ll need to know quite a bit more about PV modules, racks, inverters, charge controllers, disconnects, and batteries than when purchasing a system from a local supplier/installer. If you decide to take this route, you should read one of the books on solar electricity in the Resource Guide to deepen your knowledge. I’ve provided a lot of information in this chapter, but there’s much more to know. As Weiss points out, “PV systems are not plug and play.”

For years, my favorite book on solar electric systems has been The New Solar Electric Home by Joel Davidson. It presents a lot of technical information in a way that is amazingly comprehensible, and it was recently updated. Unfortunately, most of the books on solar electricity are penned by engineers or tech-heads for whom writing is not their strength. There is at least one exception, though, that might be useful to you: Johnny Weiss and his colleagues at Solar Energy International in Carbondale, Colorado have written Photovoltaics: Design and Installation Manual. This book is a manual for individuals who want to size, design, and install solar electric systems. It is generally well-written and full of good information. It should bring you up to speed on the subject so that you can size and design your own system and purchase components with confidence. I’d also strongly suggest taking a workshop or two to hone your skills. Hands-on experience is vital. You can take classes at The Evergreen Institute’s Center for Renewable Energy and Green Building, and a number of other places, including Solar Energy International in Colorado, the Solar Living Institute in California, or the Midwest Renewable Energy Association in Wisconsin. Many other educational programs have come on line in the past few years. Be sure instructors have experience and can explain this difficult subject clearly.

Be very careful when shopping for and purchasing the components of a solar electric system. This requires a lot of knowledge and attention to detail; be certain that you are working with a very knowledgeable dealer who really knows what he or she is talking about and offers solid technical support. Look for a supplier who’s been around for a long time and who will sell you what you need, not what they have in surplus. In recent years, there’s been an onslaught of Internet renewable energy suppliers. Some of them operate from remote sites; they have no inventory, so everything must be drop-shipped from the manufacturers. They typically offer little, if any, technical support. They lack expertise and may have lousy return policies. They may even charge you to replace items that they shouldn’t have sold you in the first place. As a starter, I recommend that you visit Solatron Technologies’ website (solaronsale.com) and read “Six Important Questions to Ask before Choosing an Alternative Energy Dealer.” (As a side note, I’ve purchased PV modules, Water Miser battery caps, batteries, and an inverter through this company — and even sold a used inverter through their website — and have found their service and products to be exceptional. Moreover, their website is one of the most secure sites from which you can order. I also order a lot of components from Northern Arizona Wind and Solar. There. End of free advertisements.) Another highly reputable supplier is Real Goods. They’ve got excellent, highly knowledgeable people who can help you size and select components. Other online suppliers provide top-notch service and products, too, but you need to be careful when shopping for an online supplier. Look through Home Power and Solar Today magazines. Check out each company’s website, its return policies, its expertise and level of technical support, and other aspects of their business. Does the company actually have a location, or are they operating from someone’s home? Ask friends who may have dealt with online dealers for recommendations.

Buying Solar Modules

When buying PV modules, you’ll find that you have quite a lot of options; numerous manufacturers produce several different sizes of modules. Fortunately, they’re all pretty good, so it is hard to go wrong. Given this, what criteria do you use to select a PV module?

If you are working with a local installer, he or she may have a favorite company they like to work with. In fact, most local installers are distributors for one or two of the major PV manufacturers. Call several local suppliers to see what each one offers. If you want more options and want to save some money, you can contact a reputable online source. Experienced and knowledgeable salespeople may be able to give you sound advice on which panels will work best for you. Be sure to ask for sale items, too. You can often obtain some amazing deals this way. Also, be sure to ask if their companies offer any solar kits. Solar kits are complete packages that include the modules, racks, inverters, controllers, and everything else you’ll need. Kits usually include whatever type of module the supplier can order in bulk at a deep discount, which they pass on to you.

A Short History of PV Cells

Although PVs are generally thought of as a modern invention, they were discovered a long time ago. In fact, they’ve been around for more than 100 years, according to John Perlin, author of several excellent books on the history of solar energy, including From Space to Earth: The Story of Solar Electricity. The very first cell was made by an American inventor, E. E. Fritts, from selenium with a transparent gold foil layer on top and a metal backing. When struck by light, this primitive cell produced a tiny electrical current. Fritts called his device a “solar battery.” This mysterious invention stirred considerable controversy, though. Many prominent engineers and scientists at the time proclaimed that it violated the laws of physics. How could it make energy without burning a fuel? Although Fritts is credited with developing the first solar cell, it turns out that a Frenchman, the experimental physicist Edmond Becquerel, had made one in 1839 out of two brass plates immersed in a liquid. When exposed to sunlight, this unusual contraption produced an electrical current.

Today, most commercial PV modules are made from silicon, though new and more efficient designs made from materials with space-age sounding names are in the works.

One criterion many solar buyers use when comparing modules from different manufacturers is the cost per watt. To determine this, simply divide the cost of a module by its rating in watts. The output in watts is determined under standard test conditions (1,000 watts per square meter of irradiance at 25°C/77°F cell temperature). By dividing the wattage by the cost, you can determine the cost per watt. While you’re shopping around, be sure to check out the manufacturers’ warranties. Most PV modules come with 20 to 25 year warranties.

Types of PV Modules

Solar electric cells come in three basic varieties, all made from silicon.

The first commercial solar cell produced was the single crystal cell. These were made from a pure ingot of silicon — a long, solid cylinder that was then sliced into thin wafers.

Unfortunately, producing pure silicon ingots requires lots of energy, and cutting the ingot into thin wafers produces lots of waste material that must be remelted and formed into new ingots. The process is expensive because it requires so much energy; however, single crystal solar cells (also referred to as “monocrystalline”) boast the highest efficiency of the three solar cell technologies on the market today. Single crystal cells are about 15 percent efficient — that is, they convert about 15 percent of the sunlight energy striking them into electricity. Single crystal cells are still manufactured today, and are commonly used in PV modules by a number of companies, including Sharp. All the PV modules at The Evergreen Institute are monocrystalline.

Fig. 8-13: Polycrystalline Solar Electric cells: (a) in production, (b) finished cell, and (c) modules in solar array.

Another, newer PV cell is the polycrystalline cell (Figure 8-13a). Polycrystalline cells are so named because they consist of numerous silicon crystals of varying size. They’re beautiful to behold, but slightly less efficient than single crystal models — about 12 percent, compared to 15 percent. However, because they require less energy to manufacture, they may be a bit cheaper. They are used in many solar modules today.

Fig. 8-14: Solar Roofing. Amorphous silicon ribbons can be used to make (a) long rolls of material that can be applied to standing seam metal roofing and (b) solar shingles. Both are forms of building-integrated photovoltaics.

Silicon solar cells can also be produced by depositing thin layers of silicon on a thin metal or glass backing. This technology is known as amorphous silicon. It uses less energy, and less silicon, but is less efficient than either the single crystal or polycrystalline cells — and they’re only about 8 percent efficient.

Amorphous silicon technology was first used to create tiny solar cells for calculators and watches. However, amorphous silicon is damaged by direct sunlight and offered very low conversion efficiencies — only about 5 percent. In the years that followed the introduction of amorphous silicon solar cells, however, manufacturers have found ways to layer thin film materials to boost efficiency to about 8 percent and to make this material resistant to photodegradation. Today, thanks to this research, amorphous silicon is being used to produce solar modules. UniSolar produces amorphous silicon in long rolls with sticky backing that can be applied to metal roofing (Figure 8-14a). This is called PV laminate or PVL. It can only be applied to standing seam metal roofing. UniSolar also once manufactured solar cells that were incorporated in roof shingles, as in 8-14b, although this product has been yanked off the market — possibly for good — for a number of reasons beyond the scope of this book.

Thin coats of amorphous silicon can also be sprayed on glass, creating solar modules and solar electric window glass that produces electricity from sunlight. This application is ideal for skylights and glass canopies, like those over gas pumps at gas stations. It is being used in large commercial buildings, too.

Thin film glass and solar roofing materials are called building-integrated photovoltaics and are very popular these days. Be careful, though, because they do have some downsides. Solarized glass located on the south side of a building receives much less solar energy in the summer than the winter due to the sun’s high angle in the sky. This can dramatically reduce a system’s annual output. (Remember Dan’s rule of technology: Just because something seems like a good idea, doesn’t mean it is!) Although you may want to consider solar roof materials like PVL, if you are thinking about installing solar electricity and re-roofing your home, a coated glass skylight is probably not going to be an affordable option just yet.

Some manufacturers also sell solar roof shingles. These are small solar modules that take the place of roof tiles. They often blend very nicely with the roof, and are therefore popular among individuals who are interested in maintaining the appearance of their homes. They do have limited application, however, as most homes have conventional shingle roofs.

Buying an Inverter

Inverters are a key component of virtually all residential solar electric systems. They come in many shapes, sizes, and prices. When purchasing an inverter from a local supplier who’s also going to install the system, your choices may be relatively limited. Installers typically have inverters they like — and trust — and will probably choose among those that fit your needs. Even though a local supplier/installer will do the thinking for you, you should still understand something about inverters so you don’t get stuck with a model that doesn’t work for you.

First and foremost, you need to determine whether you need an inverter for a grid-connected or off-grid system. Second, when selecting an inverter for a battery-based system, be sure that its voltage corresponds to the voltage of the battery bank. As noted earlier, battery banks in off-grid solar electric systems are wired at either 12-, 24-, or 48-volts (the most common are 24- and 48-volt systems; 12-volt systems are common in small applications such as cabins or summer cottages). In olden days, the array produced 12-, 24, or 48-volt electricity, and the inverter would boosts the voltage to 120 volt AC electricity. In off-grid systems, the array, charge controller, battery bank, and inverter had to be wired to the same voltage. Today, thanks to advances in charge controllers, it is no longer necessary for all the components to match. You can, in fact, wire the array to a higher voltage to increase efficiency. The charge controller then converts that to DC electricity that is compatible — voltage-wise — with the inverter and battery bank. In these systems, the charge controller, inverter, and battery bank must all have the same voltage rating.

The next selection criterion is the wave output form. There are two types: modified sine wave and sine wave. Basically, the form of the output wave tells you how pure the electricity is. Sine wave is purer than modified sine wave (technically it should be called “modified square wave”). Sine wave is equivalent to the electricity you buy from the electrical grid. Sine wave inverters are also more expensive.

All grid-connected inverters must produce sine wave electricity. Off-grid inverters can be sine wave or modified sine wave. Unless money is a problem, I strongly recommend that you purchase a sine wave inverter, not a modified sine wave inverter. Sine wave inverters produce “cleaner” AC electricity, so they tend to work much better with modern electronic equipment. In fact, some of the newest electronic equipment — like most of the energy- and water-efficient frontloading washing machines — won’t operate on modified sine wave electricity. The sensitive computers that run these washing machine just plain won’t work! Some laser printers also have a problem with modified sine wave electricity, as do some cheaper battery tool chargers. Furthermore — and here’s an important thing — electronic equipment like TVs and stereos give off a rather annoying high-pitched buzz when they’re operating on modified sine wave electricity.

When selecting an inverter for a grid-connected system, you will need to match the inverter to the array. More specifically, you need to be sure that the output of the array matches the input of the inverter (in volts). For off-grid inverters, you will need to check continuous output, surge rating, and efficiency.

Continuous output power is a measure that tells you how many watts an inverter unit can produce on a continuous basis (provided there’s electricity stored in the battery bank). The Xantrex RS3000 inverter, for instance, produces 3,000 watts of continuous power, which means it can power a microwave using 1,200 watts, an electric hair dryer using 1,200 watts, and many other smaller loads simultaneously.

Surge rating is the wattage a battery-based inverter can put out over a short period, usually around five seconds. The Xantrex RS3000 inverter has a 7,500-watt surge power rating (60 amps). That means it can produce a surge of power up to 7,500 watts. This is important because many appliances and power tools (washing machines, refrigerators, and table saws, for example) require a surge of power when first turned on. It’s required to get the ball rolling, so to speak — to start parts moving, overcoming inertia. Typically, these devices only need this power surge for a tiny fraction of a second, but without it, the tool won’t start. (Kind of like people who need their morning coffee to get going.)

Next is efficiency.

Inverters consume energy to change DC to AC and to boost voltage. Efficiency should be high on your list whether you are buying a grid-connected inverter or an off-grid inverter. So, look for models with the highest efficiency possible. The Xantrex RS3000 has a peak efficiency of 90 percent. The Sunny Boy 2500U is 93 to 94.4 percent efficient.

If you are going to have a battery bank, you’ll need an inverter that contains a battery charger. Today, all battery-based sine wave and modified sine wave inverters have the additional circuitry needed to charge batteries from an external AC source (a generator or utility power, for example). That’s why they are called inverter/chargers. Even if you are not planning on installing a battery bank, you may want to consider purchasing an inverter with a battery charger — in case you later decide to add a battery bank for backup or go off-grid.

You should also check into noise, especially if the inverter is going to be installed inside your home. Be sure to ask about this feature upfront, and, if possible, ask to see a model you are considering in operation to be sure it’s quiet. My Trace inverter, now manufactured by Schneider Electric, is located inside my home. The manufacturer describes it as quiet, but the unit emits a loud and annoying buzz. (If that’s their notion of quiet, they must be deaf.) The first six months after I moved in, it drove me nuts, though now I’m used to it. The Sunny Boy inverters define the word quiet. Outback inverters and Fronius inverters I’ve installed are also extremely quiet.

When considering an inverter, there are a number of other things to look for: ease of programming, the type of cooling system in the inverter, and (for battery-based inverters) search mode power consumption. My first Trace inverter (DR2424, modified sine wave) was a dream when it came to programming: all of the controls were manual. I simply adjusted a dial to change the settings and I was done. My new Trace inverter (PS2524, sine wave) works wonderfully in all respects except for programming, which is a nightmare. I have found the digital programming to be very difficult, and the instructions don’t help. You pretty much have to be a genius to figure them out. So find out in advance how easy it is to change settings, and don’t rely on the biased view of a salesperson or a knowledgeable tech person. Ask friends or dealers/installers for their opinions or, better yet, have them show you.

Last, but certainly not least, is the power consumption under search mode. Search mode is an operation that lets an inverter operating off batteries to turn off completely when there are no active loads in a home — no devices or appliances drawing power. To stay on the alert, though, inverters send out tiny pulses of electricity that search for a load (a closed circuit). If you switch on an appliance, the PV system immediately kicks into gear and starts supplying electricity via the inverter to meet the demand. The search mode saves energy because it allows the inverter to shut down and go to sleep (with one eye open). This is especially beneficial at night — when you go to bed, or shut down your business.

A search mode consumption of under 0.5 amps is good. Be sure when buying an inverter that the supplier, be it an Internet supplier or a local vendor, takes the time to determine which inverter is the correct choice for you. Ask lots of questions. Consult with experts. Or better yet, hire an experienced professional to install your system.

Supplying 240-Volt Electricity

Many homes require 240-volt electricity to operate appliances such as electric clothes dryers and electric stoves. As a general rule, you should try to avoid such appliances, not because a solar system cannot be designed to take care of them, but because they use lots of electricity, so you’ll need many PV modules to supply them.

If you must have 240-volt AC electricity, don’t despair. All grid-connected inverters produce 120- and 240-volt AC. Some battery-based inverters, like the Xantrex XW series inverters, produce 120- and 240-volt AC. For other inverters, you will need to wire two 120-volt AC inverters in series to produce 240-volt AC. You can also install a step-up transformer such as the Xantrex/Trace T-240. This unit takes 120-volt AC electricity from an inverter and steps it up to 240-volt AC.

Buying Batteries

If you are going to install a grid-connected solar electric system with a battery bank or an off-grid system, you’ll need batteries. The more energy your home consumes and the longer the cloudy spells, the more batteries you’ll need. (I’ll say it again: be sure to cut your electrical demand through efficiency and other measures first. Efficiency will save you a fortune on PV modules and batteries.)

Most batteries used in solar electric systems are 6-volt, deep-cycle flooded lead acid batteries. Trojan L-16s have been the mainstay of the solar electric industry for years, but their dominance in the battery market has been challenged in recent years by several batteries from other companies, among them US Batteries and Rolls Batteries (Figure 8-15).

Batteries are wired in a combination of series and parallel circuits to produce 12-, 24-, and 48- volt systems. The 48-volt systems are the most efficient. As you will soon see, batteries are rated by their capacity to store electricity. The common measure for battery storage is amp-hours: an amp-hour is one amp of current flowing for one hour. A battery in a solar electric system should probably store 350 to 420 amp-hours of electricity to be useful.

When shopping for batteries, it’s hard to go wrong. Most deep-cycle flooded lead acid batteries manufactured for solar systems are pretty good. But be sure to check out the storage capacity and manufacturer warranties first. The Surrette S460 comes with a seven-year warranty. The manufacturer will replace the battery free of charge for the first two years if it fails. After that, the manufacturer will replace it at a prorated value. Although lead acid batteries are less efficient than some of the newer battery technologies on the market today, old batteries are recycled. In fact, nearly 100 percent of the lead from used batteries makes its way back into the production cycle.

8-15: Lead Acid Batteries. The Surrette battery shown here is an excellent choice for a solar electric system.

Solar electric systems can run on ordinary car batteries, but not for long. Car batteries are not designed for deep discharging — drawing off lots of power. They’re the rabbits of the battery world; they’re designed to crank out tons of amps to start a car. What you need is a tortoise — a battery that can give you all it has for long periods of time. No sprinters need apply. So be sure not to make the mistake of running a solar electric system on car batteries. It is a waste of your time and money.