One

IN THE NAME OF THE CROWN

1776–1821

Fr. Junipero Serra founded San Juan Capistrano on November 1, 1776, amid tumult and uncertainty. The proceedings were witnessed by a delegation of soldiers and curious onlookers from the Acagcheme tribe that would be given the name Juaneno.

The mission was part of a Spanish plan to establish missions, military outposts, and settlements in California in order to spread Catholicism, discourage settlement by other foreigners, and act as a buffer between native populations and the European culture that would be imposed on them.

Gathering converts from the area, the mission thrived in its earliest years. There were 944 Indian neophytes by 1796, with 1,649 baptisms. Fields were planted with wheat, barley, corn, and beans, and there were herds of cattle and horses roaming a vast territory. Buildings were constructed, including 40 adobes in 1794 and 34 more in 1807. These were outside the mission walls and were primarily used for housing.

The most ambitious project was the Great Stone Church, begun in 1797 and completed in 1806. Despite having thick walls and domes of masonry, the building was destroyed in an earthquake in 1812 that killed 40 people and demoralized the mission community. Falling into a decline thereafter, the mission was plundered by the pirate Hippolyte Bouchard in 1818, and faltered both in its conversions and its production, never regaining the glory of its beginning.

King Carlos III was on the throne of Spain when Mission San Juan Capistrano was founded in 1776. He granted control of thousands of acres of land to the missionaries, who were to hold it in trust for the Indians. The Spanish Crown used three institutions to colonize California: the pueblo, the presidio, and the mission. All three relied on a royal land grant for their existence. The missions were responsible for converting Native Americans to Christianity, preparing them to live in a Western European culture, and to make them loyal subjects of the crown. This “training” was to take 10 years, but in fact it took 50 before land was returned to the Indians. Carlos III died in 1789.

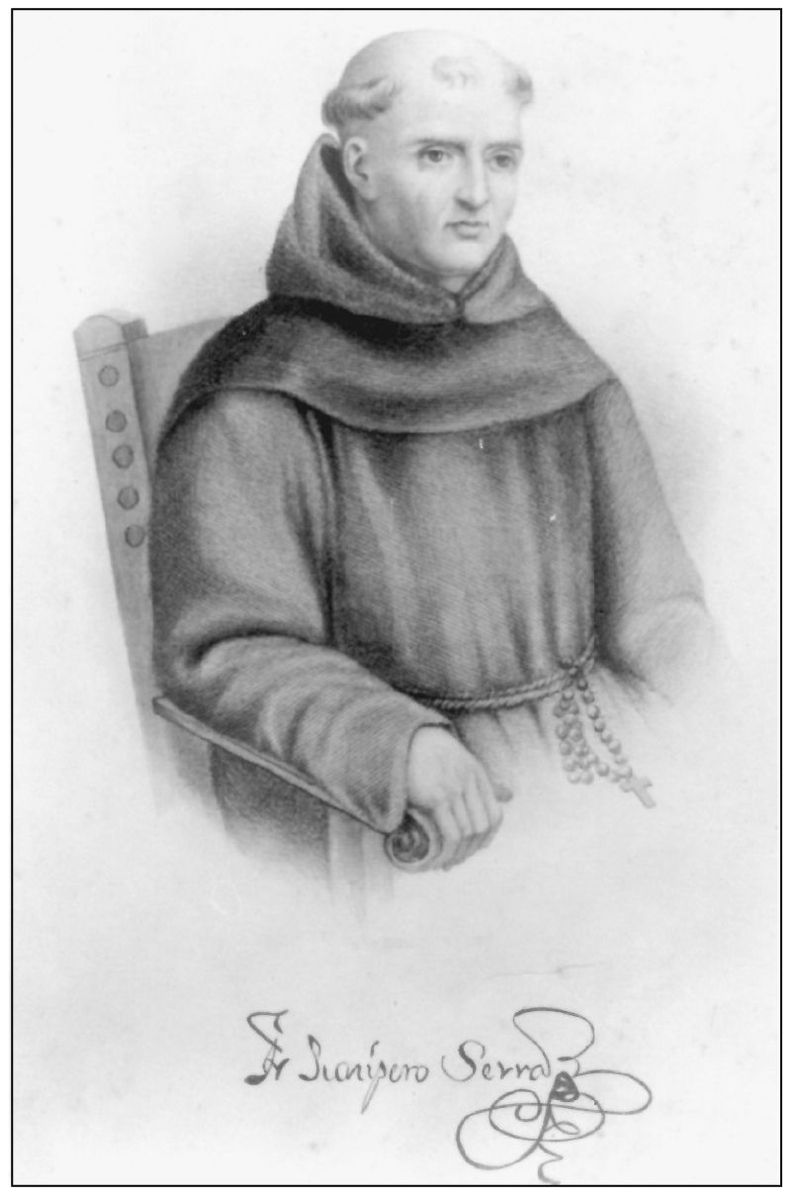

Fr. Junipero Serra, a Franciscan scholar from Mallorca, was appointed to undertake the establishment of missions in California. He founded Mission San Juan Capistrano as the seventh in the Alta California chain, naming it for St. John of Capestrano, an Italian saint whom he admired. He first attempted to establish it in 1775, but an uprising in San Diego delayed the mission’s founding until November 1, 1776.

The founding document for the mission demonstrates how interdependent mission settlements were in California. Father Serra itemizes the contributions of grains, livestock, and tools that came from Mission San Gabriel. These were used for food and to establish crops and herds. Articles for the church—the first building to be constructed—were also sent.

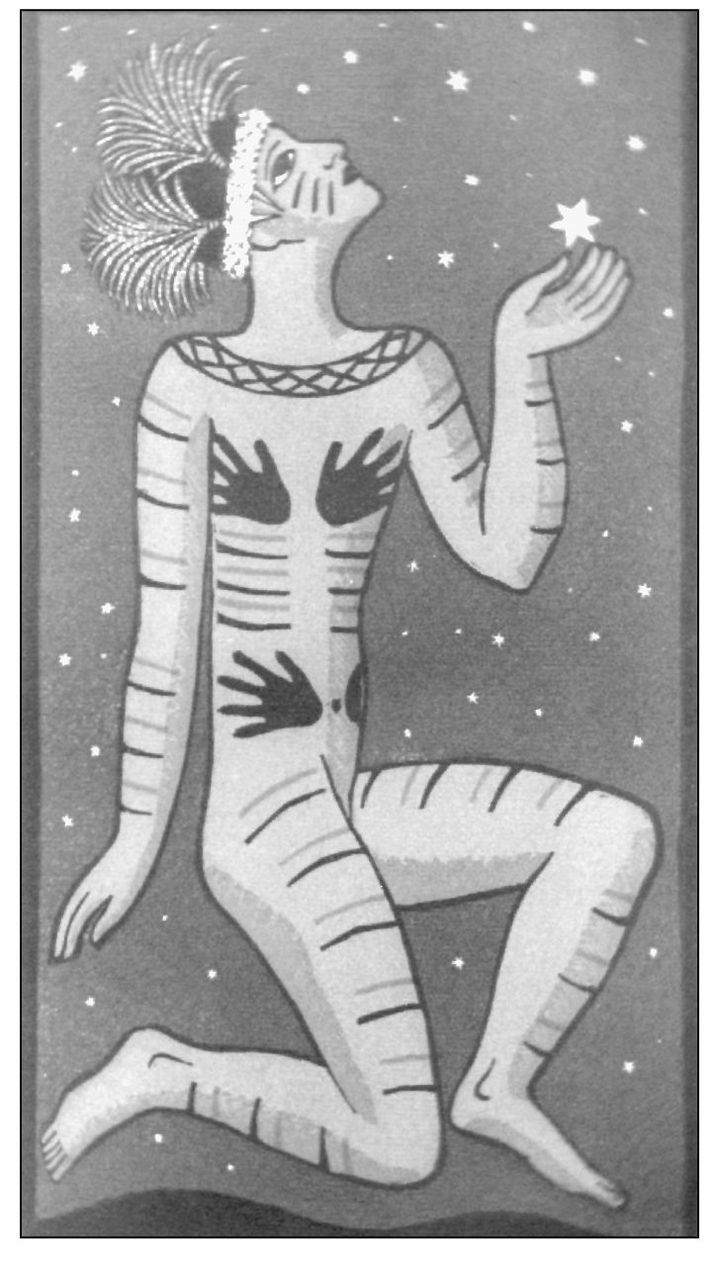

Fr. Geronimo Boscana was assigned to the mission from 1814 to 1826. The life of a missionary was occupied with teaching manual skills and spiritual concepts, with little time for intellectual pursuits. In his spare time, Boscana wrote about the culture of the Juaneno Indians in his care, calling the manuscript Chinigchinich, the name of the deity they worshipped.

In Chinigchinich, there is a story of creation that was important to the Juaneno culture. An artistic rendering of a figure representing Chinigchinich coming out of the sky appears in a 1933 edition by Fine Arts Press. It was a linoleum-cut color print and is one of a series of prints in the book. Geronimo Boscana’s manuscript first appeared as an appendix to a 19th-century travel guide and remains the earliest description of Juaneno life.

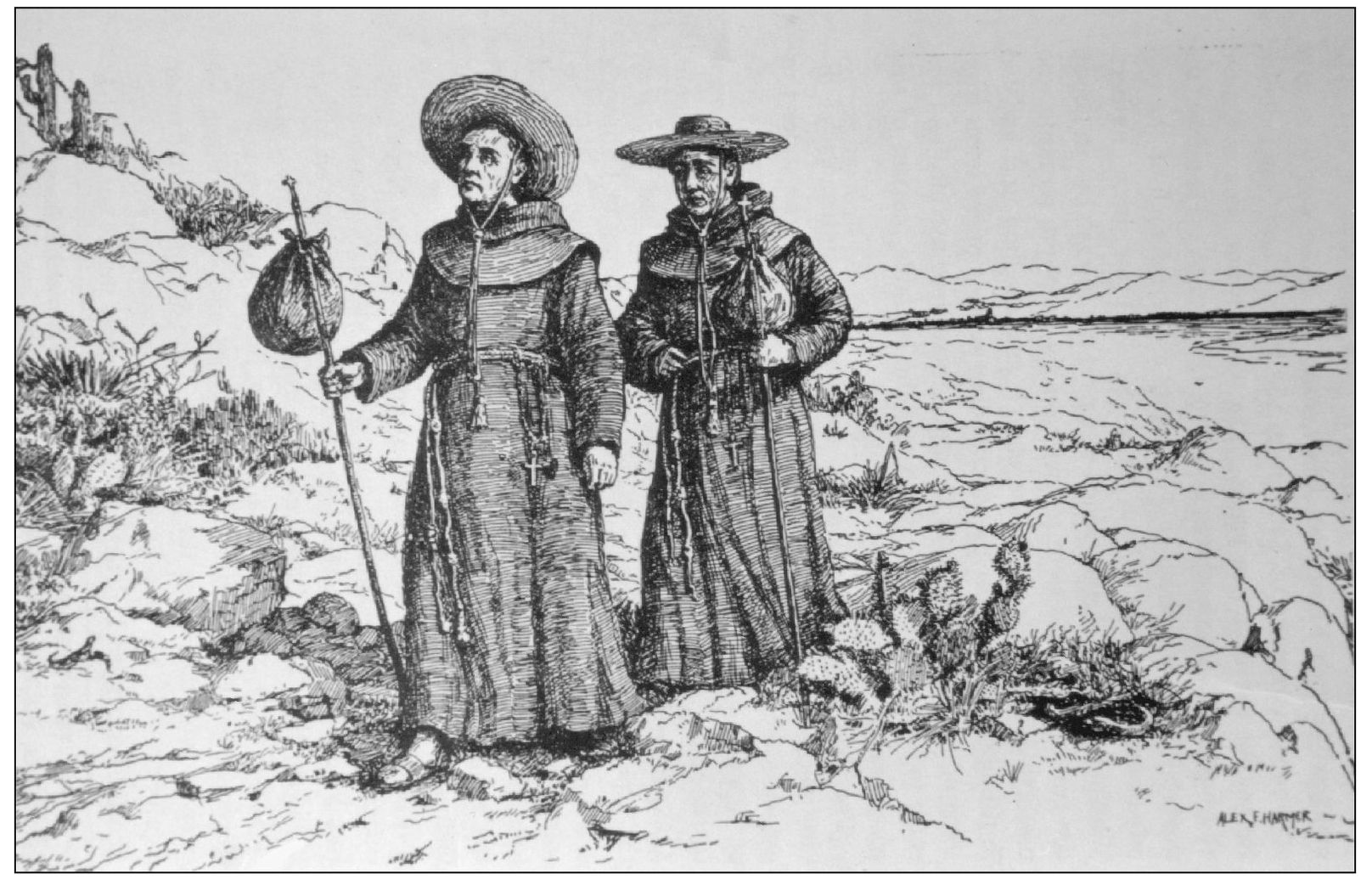

Early Franciscans, making their way on foot, appear in this artist’s drawing. Two missionaries accompanied the expedition of Gaspar de Portola in 1769. Their task was to scout sites for future missions and to tend to the spiritual needs of the 64 “leatherjacket” soldiers in the group. Franciscans were trained as scholars and were often ill equipped for the rigorous life on the frontier, but soon they adapted.

The cattle brand for Mission San Juan Capistrano was represented by the intertwined letters “CAP.” At the height of its prosperity, around 1811, the mission owned 14,000 cattle, 16,000 sheep, and 740 horses. It also produced 500,000 pounds of wheat, 190,000 pounds of barley, 202,000 pounds of corn, and 20,600 pounds of beans. It also created enough hides and tallow for trade with Spanish ships who brought specialty items.

Bells were very important to mission life, regulating prayer times and daily activities, and even tolling in different patterns when there was a death of a man, woman, or child. The original two bells of the mission, rung at its founding, are not among those pictured and it is not known when they went out of service. However, those remaining are very old; the larger two were cast in 1796 and the smaller in 1804.

The buildings of the mission are shown in this drawing. The time period depicted is between 1806 and 1812 (the Great Stone Church, at right, is still standing). The barracks appear in the foreground. The most ambitious construction project was the church, begun in 1797 under the tutelage of Isidro Aguilar, a master mason from Mexico. Unfortunately, Aguilar died before the project was completed.

The first baptism in what would later be known as Orange County occurred during the Portola expedition of 1769 near what is today’s San Clemente. Fr. Juan Crespi and Fr. Francisco Gomez, the two missionaries accompanying the expedition, heard about two Indian baby girls near death. They took a contingent of soldiers and were able to find them. They baptized them, naming them Maria Magdalena and Margarita. The incident was entered into Crespi’s diary on July 22. The site of the baptisms was given the name Canon de Los Bautismos, but today is known as Cristianitos Canyon. This drawing, depicting the event, first appeared in Zephyrin Engelhardt’s, Mission San Juan Capistrano.

This painting depicts the front area of the mission during the height of its activity, even showing a construction project underway at left. Neophytes of the mission were taught to cultivate crops, tend livestock, make leather products and clothing, and prepare food. They also learned songs, prayers, and biblical lessons. Once attached to the mission, they were not allowed to leave and were disciplined if they tried to run away.

Various relics from the past are still on view today in the Mission Museum and other locations. Pictured here are a hand-carved chest, a round baptismal font, a rustic circle of bells that were rung by turning a crank (used during Lent), and a piece of a hand-carved wooden wall decoration. The mission also owns early vestments and prayer books that are not shown.

This is a diagram of the mission quadrangle as it may have looked originally. Although drawn for a later restoration project by Judge Richard Egan and Arthur Benton, it points to how missions were built with defensible quadrangles. The soldiers’ quarters are outside the walls. The numbers correspond to a list of how each room was used. The Serra Chapel is the longest rectangle on the right side of the quadrangle and the area just to its right was the cemetery. The Great Stone Church is shown in the lower right corner. The variety of uses listed for the buildings show that the mission was truly a self-contained community.

On December 8, 1812, during a morning mass, an earthquake demolished the Great Stone Church. According to Frs. Francisco Suner and Jose Barona, who were then in charge, the tower tottered twice and at the second shock it fell on a portal, causing the roof to cave in all the way to the transept. Forty bodies were found, most near a door whose latch had stuck due to the shaking.

For years after the 1812 earthquake, only rubble and the rear walls of the structure were all that remained of the Great Stone Church. Later a group of parishioners would try to restore it using adobe walls (center left), but the walls would wash away before a roof could be built, so they gave up. After the tragedy, the old Serra Chapel was put back into full use.

The mission death register lists each person by name, age, and condition. After the earthquake of 1812, it was Father Barona’s job to list each victim. There were 4 married men, 3 single men, 25 married women, 4 widows, 2 single women, and 1 male child—a total of 39 deaths altogether. Another victim, a married woman, was discovered two months later, bringing the toll to 40.

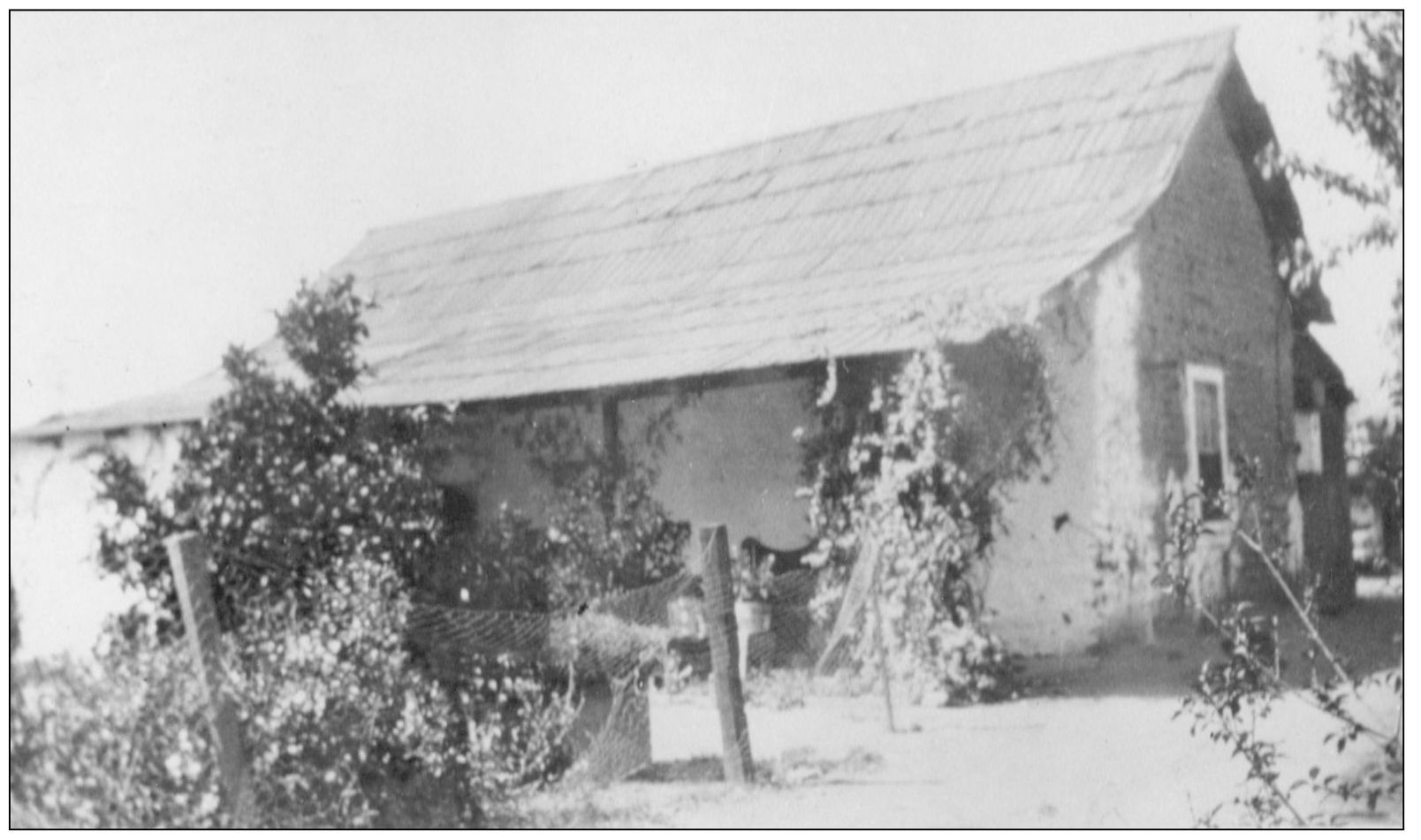

In 1794, 40 adobes were constructed outside the mission grounds for neophytes and others associated with the mission. One was the Rios Adobe, shown here in a later picture, which was occupied by a soldier named Feliciano Rios. In 1807, 34 more adobes were built, some of which are still standing today.

Hippolyte Bouchard, a privateer working for insurgents in the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata (Argentina), raided missions along the coast, demanding that Californians rid their allegiance to Spain. He and a sister ship approached Mission San Juan Capistrano on December 14 and 15, 1818, anchored in the bay, and after being refused supplies he burned and looted parts of the mission community. His men also consumed considerable amounts of wine and brandy before heading back to their ships, causing a few to desert.

These are kiitchas, dwellings that the Juaneno Indians lived in prior to the introduction of adobe homes by the Spanish.