Two

MEXICAN HIATUS

1821–1848

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, signaling the end of an era for the California missions. Largely ignored by the new government, Franciscans struggled to maintain control, but the new government had different priorities: opening ports to foreign trade, granting land to settlers who would enhance the tax base, and emancipating Native Americans to broaden the labor pool.

For the next 10 years, the mission deteriorated, the Indians left, and mustard reclaimed tilled fields. By 1833, the mission was secularized and most of its land was confiscated by the government for redistribution. A series of mission “administrators” were appointed, but most gave up and left, and the Indian pueblo that was formed in 1834 was declared a failure. Bowing to pressure, Gov. Juan Bautista Alvarado reorganized the pueblo in 1841, formally recognizing San Juan Capistrano as a town in its own right. Land was divided into house and garden lots with farm equipment held by the government and distributed as needed. Land had to be occupied within one year or it could be redistributed.

Despite grand plans, the town struggled and many would-be settlers stayed away. From 1842 to 1846, the mission itself was abandoned, falling prey to vandals and the elements. A debt-ridden burden, the mission buildings, grounds, and orchards were sold in 1845 at public auction by Gov. Pio Pico. John Forster and James McKinley purchased them for $710 in gold and hides. Forster, Pico’s English brother-in-law, eventually acquired sole ownership and he and his family moved in, making the mission their primary residence for nearly 20 years.

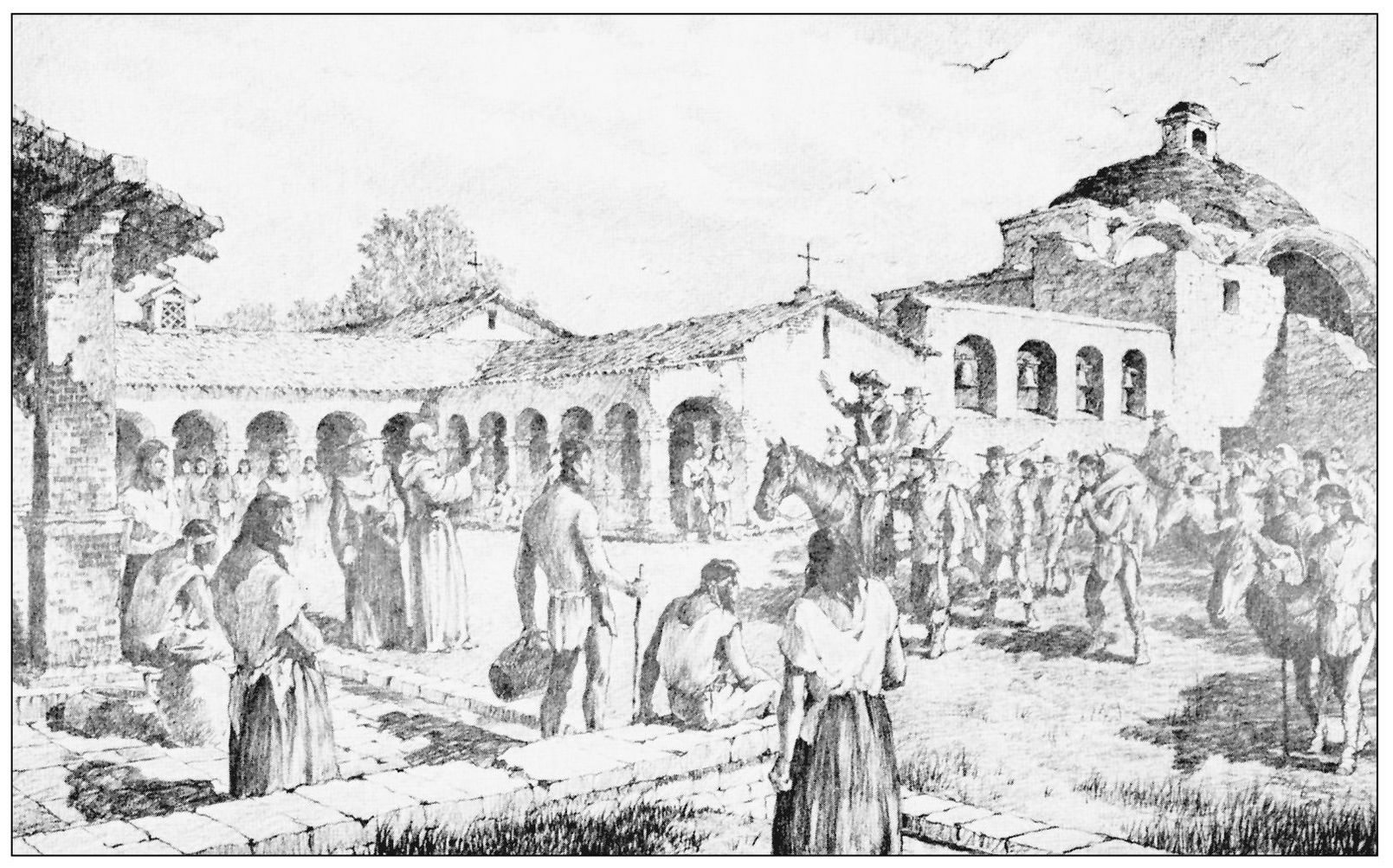

In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain and claimed California. Life would change drastically for the mission system, since they were seen as institutions of the crown. This painting by Lloyd Harting could easily be depicting the arrival of news concerning independence to Mission San Juan Capistrano—news that would result in the secularization of the missions and confiscation of their land.

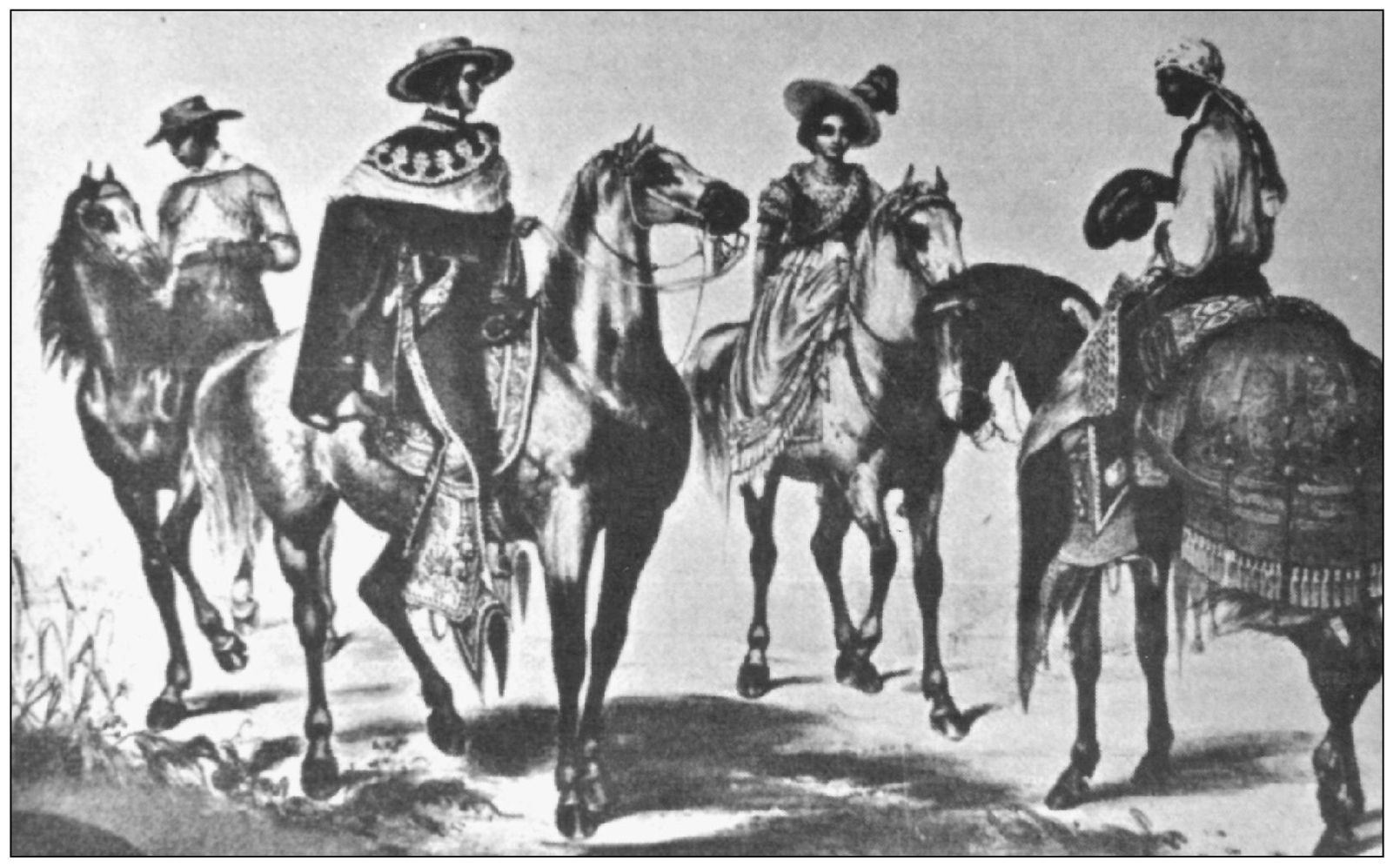

After 1831, the program of mission secularization was accelerated, and in 1833 the emancipation of all Native Americans was completed. By 1834, mission lands were confiscated, paving the way for land grants to be issued. A new society dominated by the ranchos and their owners, shown in the drawing above in typical garb, soon grew into a dominant force in California.

Juan Avila, nicknamed “El Rico,” was the original grantee of Rancho Niguel and its 13,316 acres north of San Juan Capistrano. The ranch was granted by Mexican governor Juan B. Alvarado on June 21, 1842. Juan Avila became a judge of the plains and later a justice at San Juan Capistrano. He married Soledad Yorba and lived in an adobe in front of the mission that was once a half-block long. The main house was destroyed by fire, but a portion was rebuilt and still stands today. A story of buried treasure lingers from the time of the fire where gold supposedly had to be buried quickly while the blaze was being fought. Nothing has ever been found.

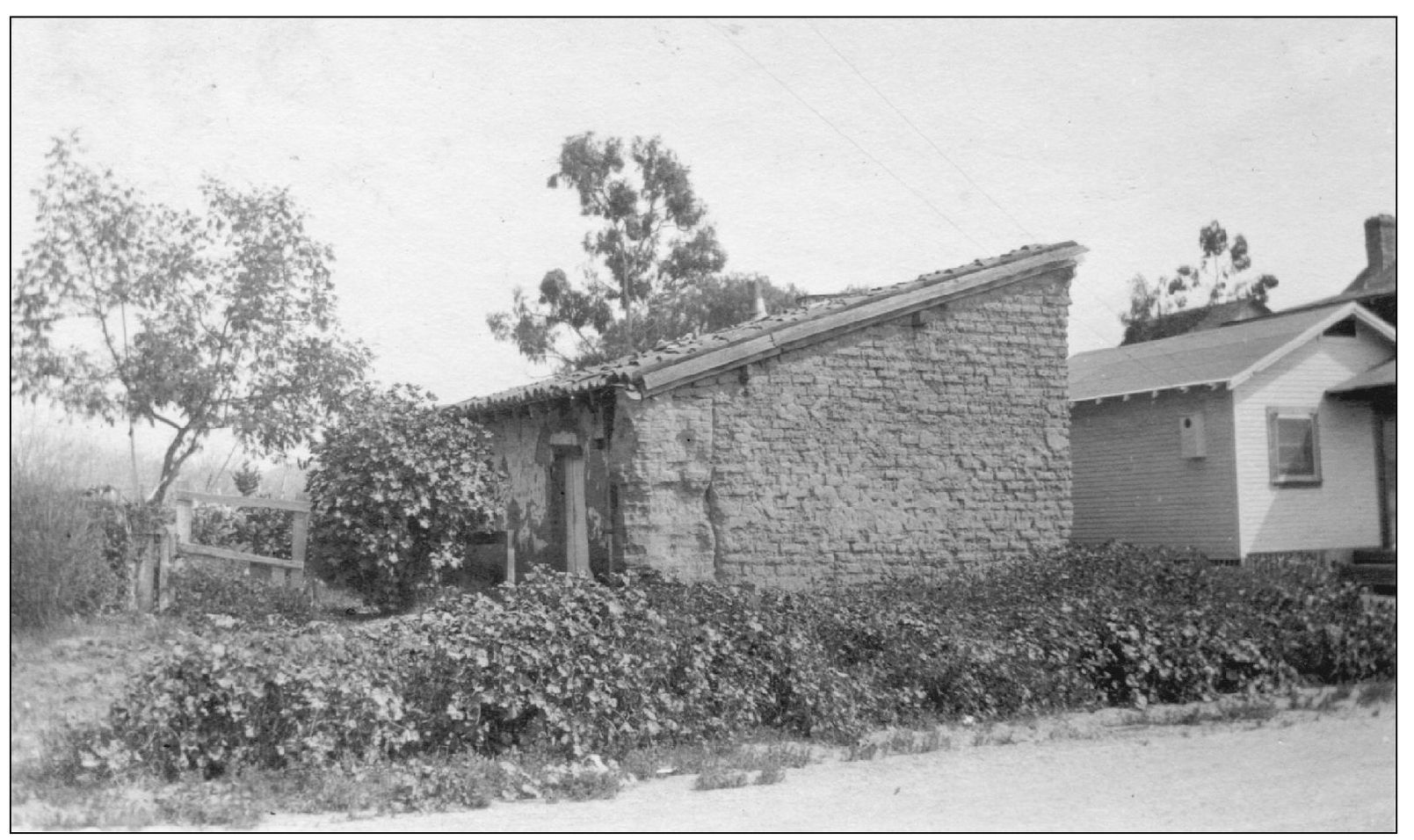

Casa Esperanza was believed to be one of the original adobes of the mission. According to mission records, 40 “little cabins” were built in 1794 and 34 more were added in 1807 to house the growing mission community. Most were built around the perimeter of the plaza and along Trabuco Creek. Blas Aguilar, a mayordomo of the mission, is said to have occupied it in 1841.

Casa Tejada, south of Casa Esperanza on El Camino Real, is also believed to be one of the original mission adobes. When Blas Aguilar bought it from Zeferino Taroge, an early Mission chanter, he combined the two and created an inner courtyard. His grandson Juan Aguilar restored both buildings before his death in 1936, but a subsequent owner eventually demolished the Casa Tejada.

Mexican independence had the side benefit of opening ports to foreign ships. Spain only allowed Spanish ships to trade in California. Brigantines, like the one above, brought supplies and specialty items from places like the East Coast of the United States, which they traded for hides and tallow. Rocks from West Coast beaches, used for ballast, can sometimes be found in cobblestone streets in the East.

Richard Henry Dana, who wrote Two Years Before the Mast and other classics, was a seaman on the ship Pilgrim, owned by merchants Bryant, Sturgis, and Company. He visited the cliff that now bears his name, Dana Point, while retrieving hides that had been thrown from the cliffs to the beach, where they were gathered and rowed out to the ships. In May 1835, he wrote that this was “the only romantic place on the coast.”

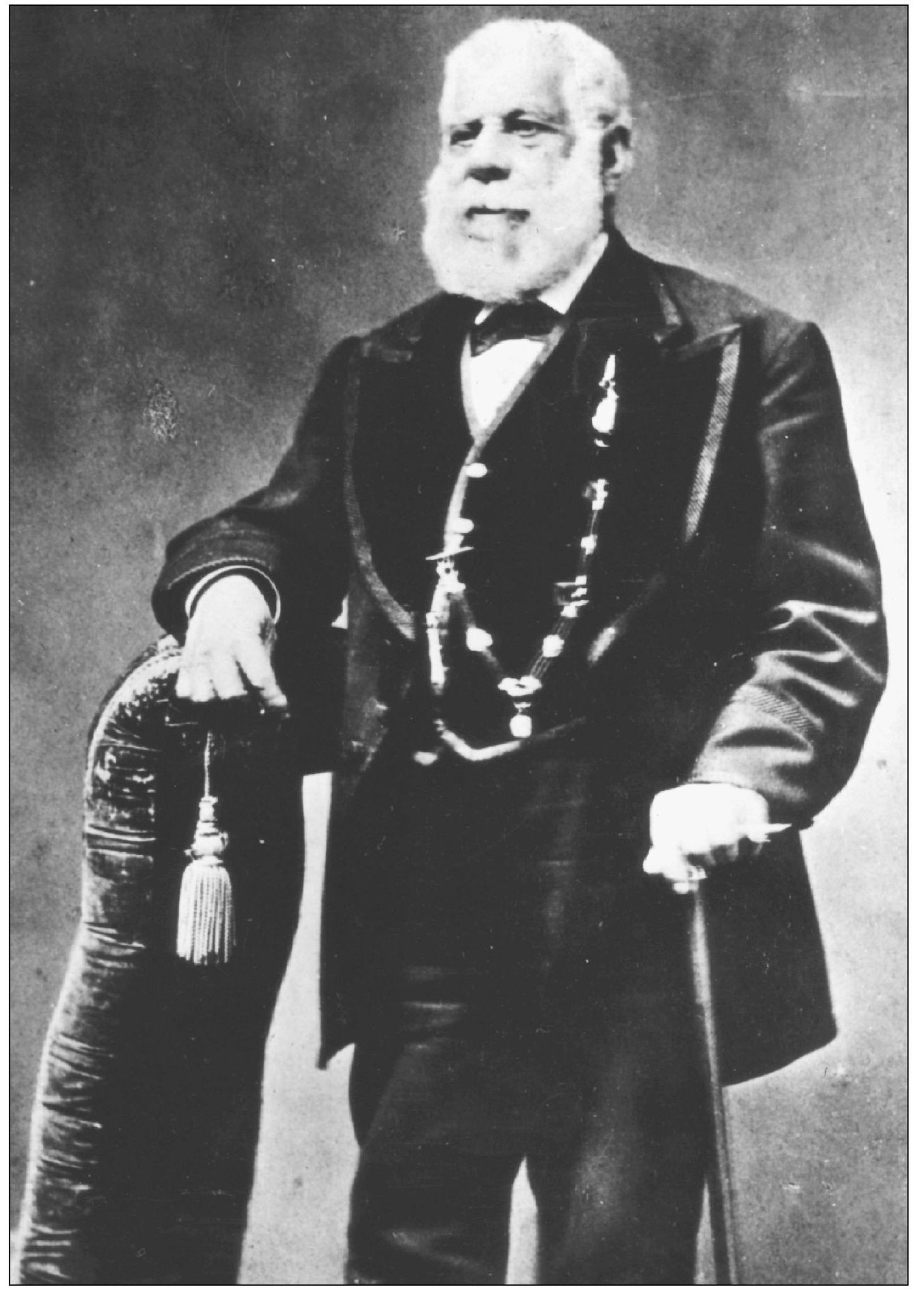

Pio Pico, the last Mexican governor of California, loved women, gambling, and politics. He was the leader of an insurgent group that overthrew the regime of Gov. Manuel Micheltorena in 1845—an act that made him the new governor, but only for a year. He is pictured here with, from left to right, Maraneta Alvarado, Ignacia Alvarado de Pico (his wife), and Trinidad de la Guerra, all women from prominent families. Pico held a number of minor political offices in the Los Angeles area on his way up. He is best known as the man who sold Mission San Juan Capistrano at public auction for $710 in gold and hides to James McKinley and John Forster; the latter was his brother-in-law.

Pio Pico fled to Mexico when the United States declared war on Mexico in 1846, stopping to hide out briefly either at the mission or Rancho Trabuco, two properties owned by Forster. Two years later, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, signaling the end of hostilities, Pico came back and took up life as a ranchero. Unfortunately his love of gambling began to play havoc with his finances and he accumulated a number of debts, particularly from horse racing, which was his passion. In 1851, he owned about 22,000 acres of land and had considerable wealth. But when he died in 1894, much of his landholdings had been foreclosed on, and he was forced to sell other properties to pay creditors.

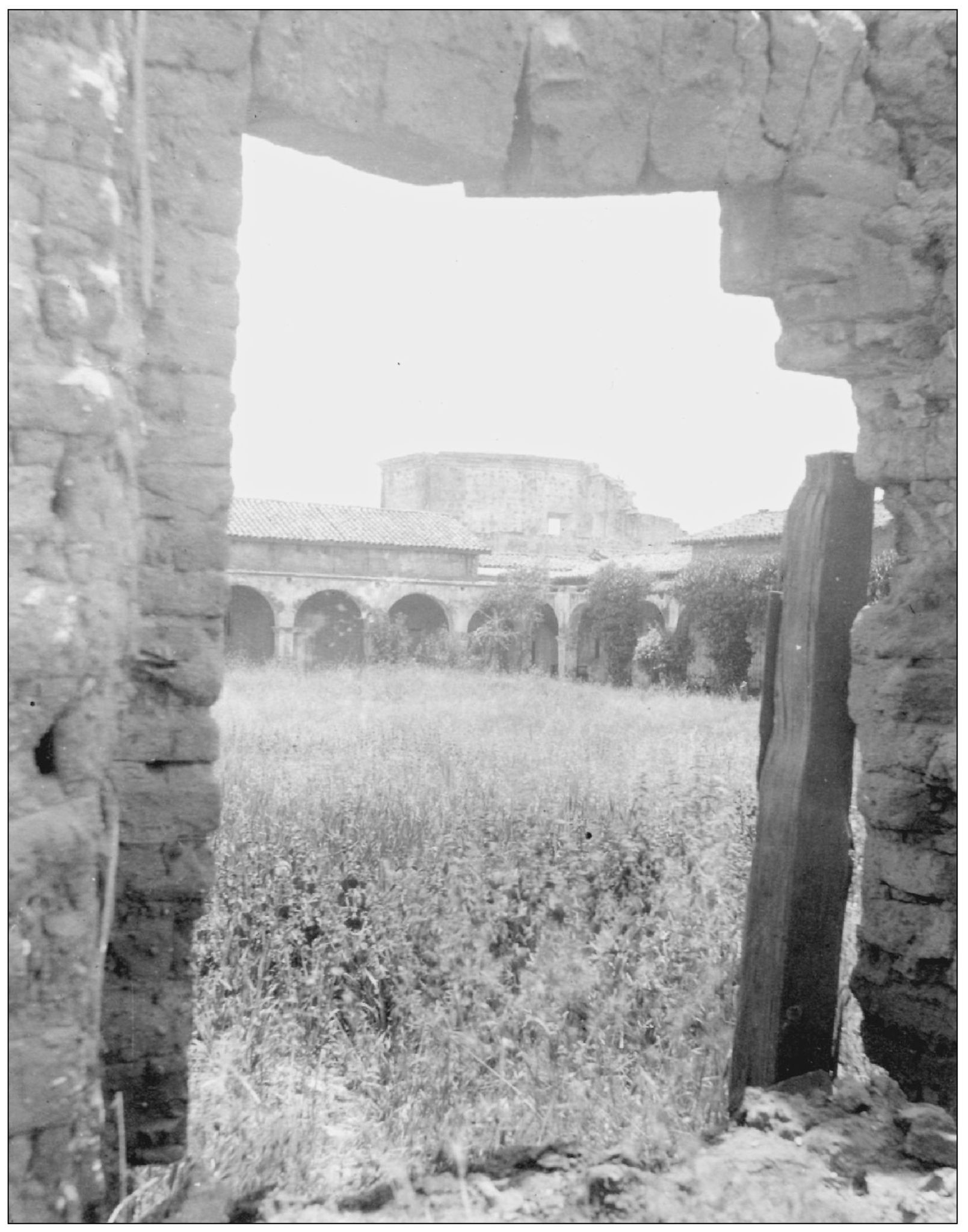

Secularization of the missions forced a once-productive society into a decline. Weeds grew in the quadrangle that once hummed with activity; walls deteriorated and roofs caved in. Gardens were untended and animals wandered freely among the ruined arches. When the Forsters moved into the mission, only a few rooms were considered habitable. During the 1830s, a series of mission administrators tried to organize an Indian pueblo and care for the sick and infirm, but nothing worked. By 1841, the mission was declared “in a ruinous state” and the Indian pueblo was dissolved. This opened land for general settlement and a charter from Gov. Juan B. Alvarado gave San Juan Capistrano official town status.

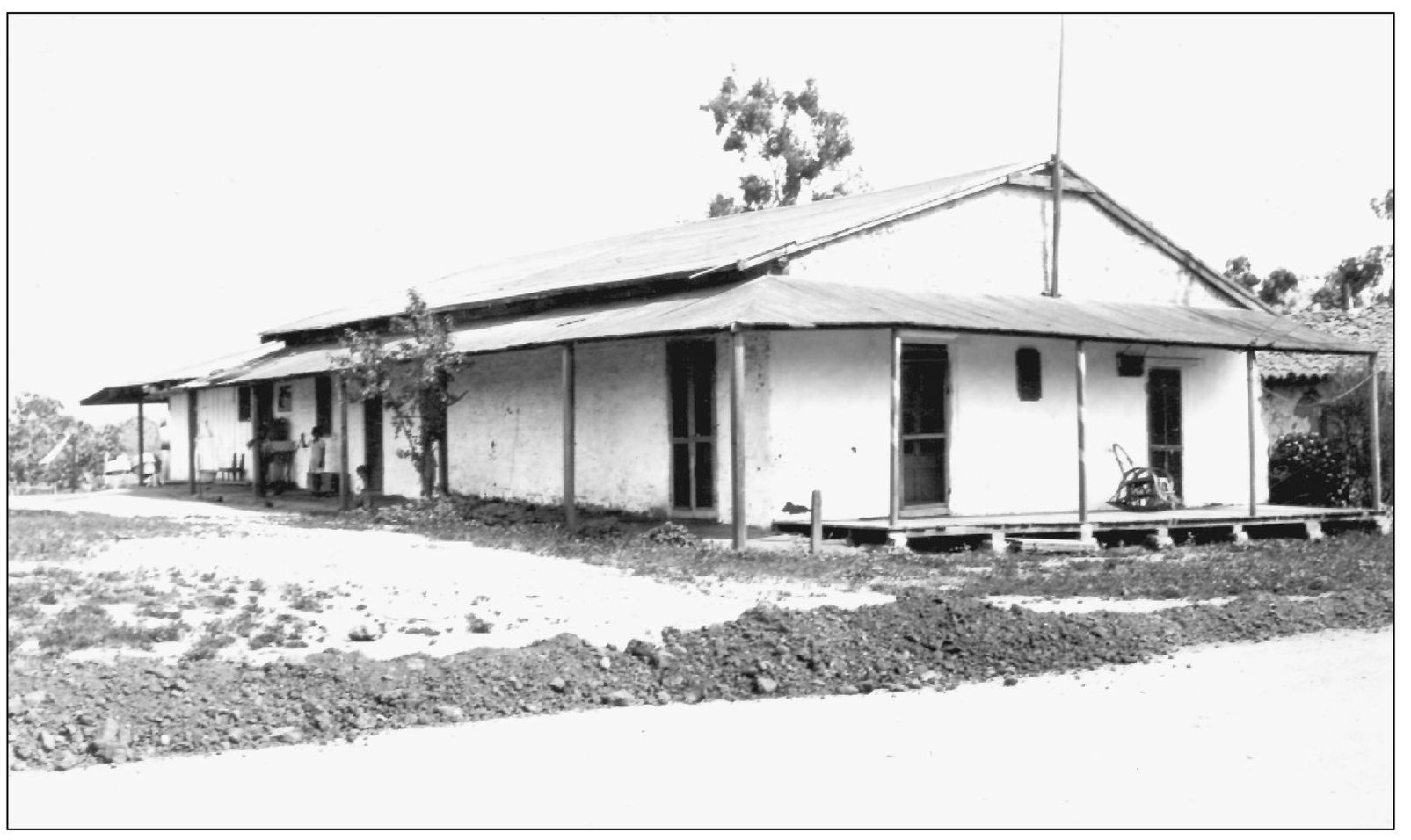

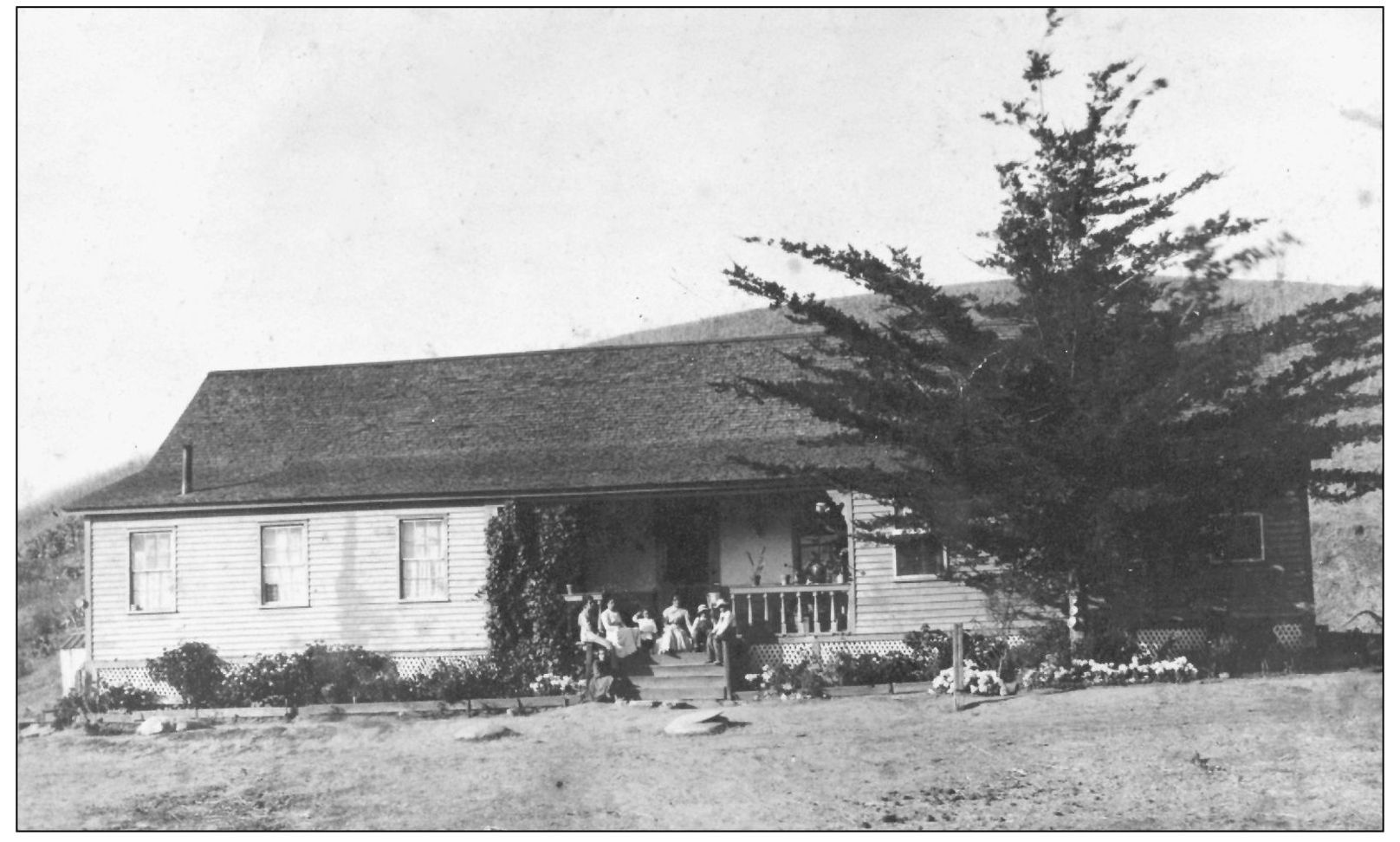

Rancho Boca de la Playa, south of the mission, was a 6,600-acre rancho granted in 1846 to Emigdio Vejar, who sold it in 1860 to Juan Avila. Avila conveyed it to his son-in-law, Pablo Pryor, and while the ranch lands changed hands, the house remained with Pryor’s descendents. An original adobe, it was remodeled over time. Pictured on the porch, from left to right, are Teresa Pryor Yorba and her children Daisy, Paul, and Bennie. Two lady guests are at far left.

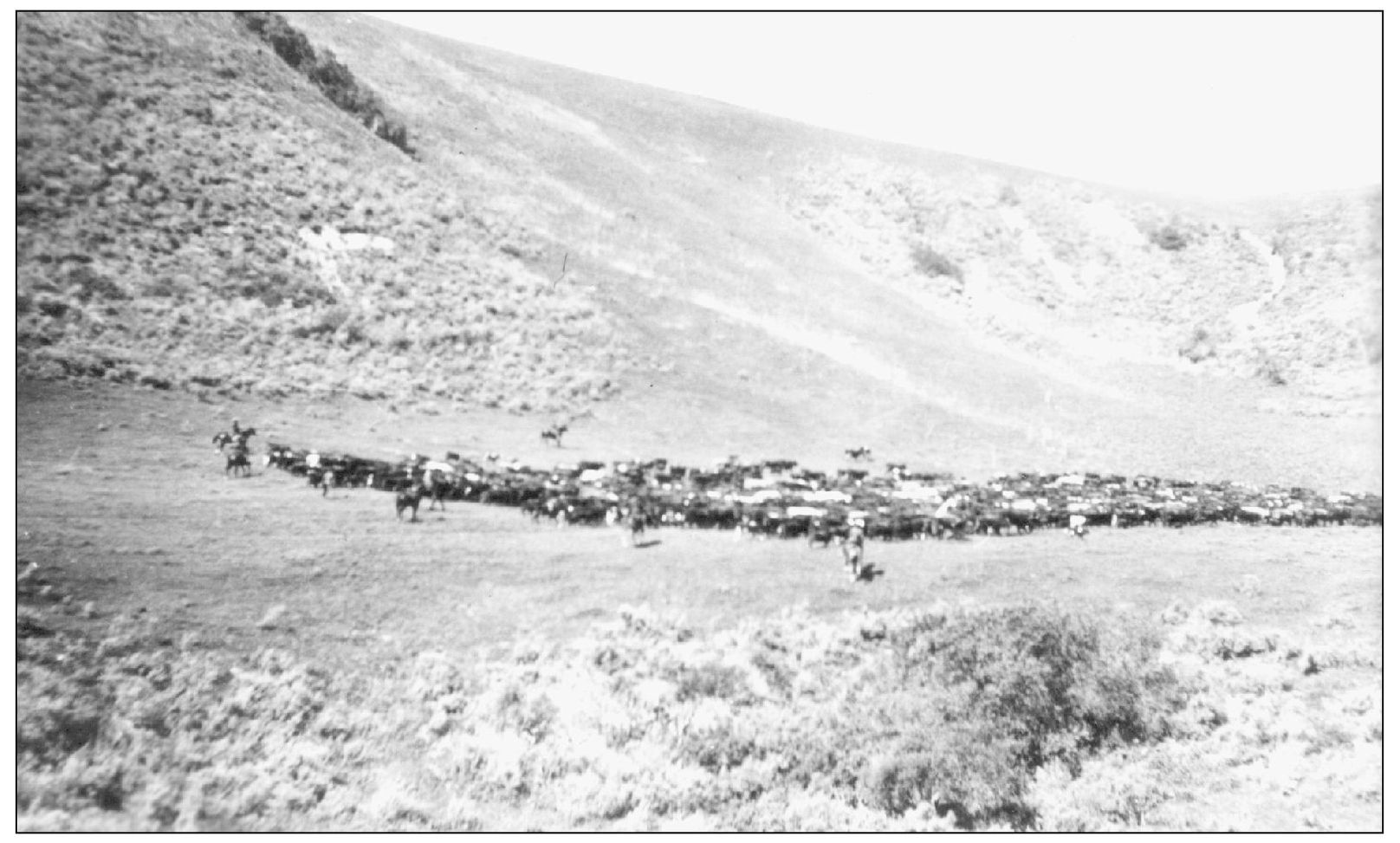

Cattle grazed on unfenced open ranges, their ownership protected only by their brands. Most of the Mexican land grant ranchos had vast herds that were slaughtered for hides and tallow. Herds were tended by vaqueros, many of them Native Americans who left the missions after secularization. Ranchos were self-contained communities, employing many people in the household, in the fields, or as artisans.

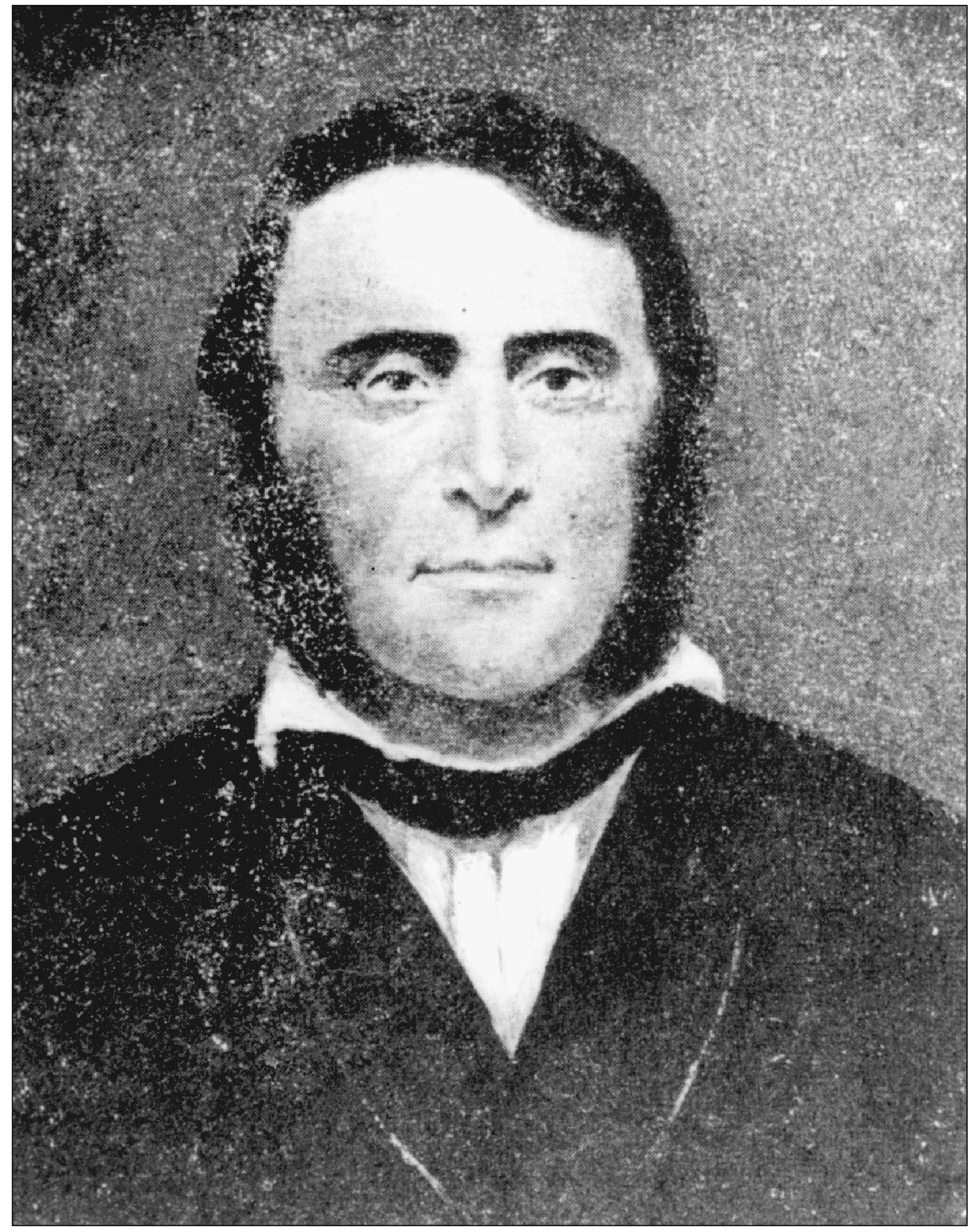

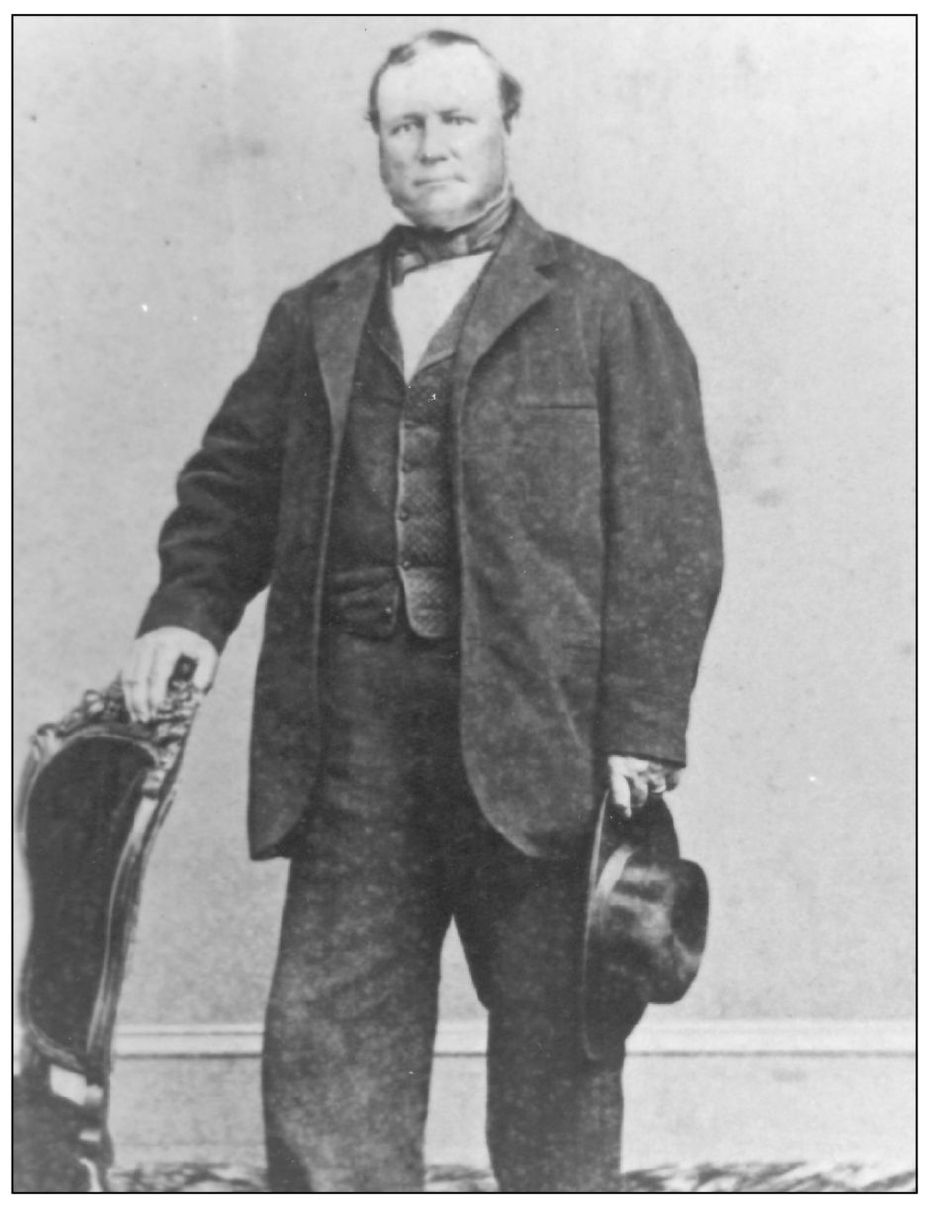

John Forster, known as Don Juan Forster, was an Englishman who became one of the largest landowners in Southern California. In addition to purchasing the Mission San Juan Capistrano, he owned over 200,000 acres of land including Rancho Mission Viejo, Rancho Santa Margarita y Los Flores, Rancho Trabuco, several pastures for grazing, and other land holdings. He married Ysidora Pico in 1837, became a Catholic, and was thus eligible for Mexican citizenship.

Ysidora Pico Forster was 23 when she married, an age considered long “on the shelf.” Her children included Marco Antonio, Francisco Pio, and John Fernando, all of whom lived to adulthood. Two girls and another son did not survive infancy. When the family moved into the mission, they lived in the former priests’ quarters, but moved out in 1864 when the mission was returned to the Catholic Church by Abraham Lincoln, who signed the document in 1865.