Three

YANKS AND RANCHOS

1848–1887

The war between Mexico and the United States, which ended in 1848, gave California to the Yanks, and by 1850 it was a state. With the discovery of gold in the north, prospectors poured into the state, creating new markets for the cattle produced by the ranchos surrounding San Juan Capistrano.

The town was rough, but had the trappings of permanence. Large ranchos dominated the landscape: Rancho Niguel to the north, Rancho Mission Vieja y La Paz to the northeast, Rancho Santa Margarita y los Flores to the southeast, and Rancho Boca de la Playa to the southwest. The smallest grant—to the Rios family—was to the west. Feudal in nature, these ranchos were often self-contained communities requiring a large workforce for both home and fields. The town provided amenities such as the church, school, stores, and saloons and a plaza for bringing products to market.

But American systems of taxation, proof of ownership, and compound interest, along with a searing drought from 1862 to 1864 followed by a smallpox epidemic, destroyed the ranchos and opened land to diversified farming, land needed by settlers moving across the continent at the end of the Civil War. Pres. Abraham Lincoln restored the mission to the church and the Forsters moved to Rancho Santa Margarita. The first township map was filed in 1875, and by 1887 the Santa Fe Railroad laid tracks through the town, initiating a new era of progress.

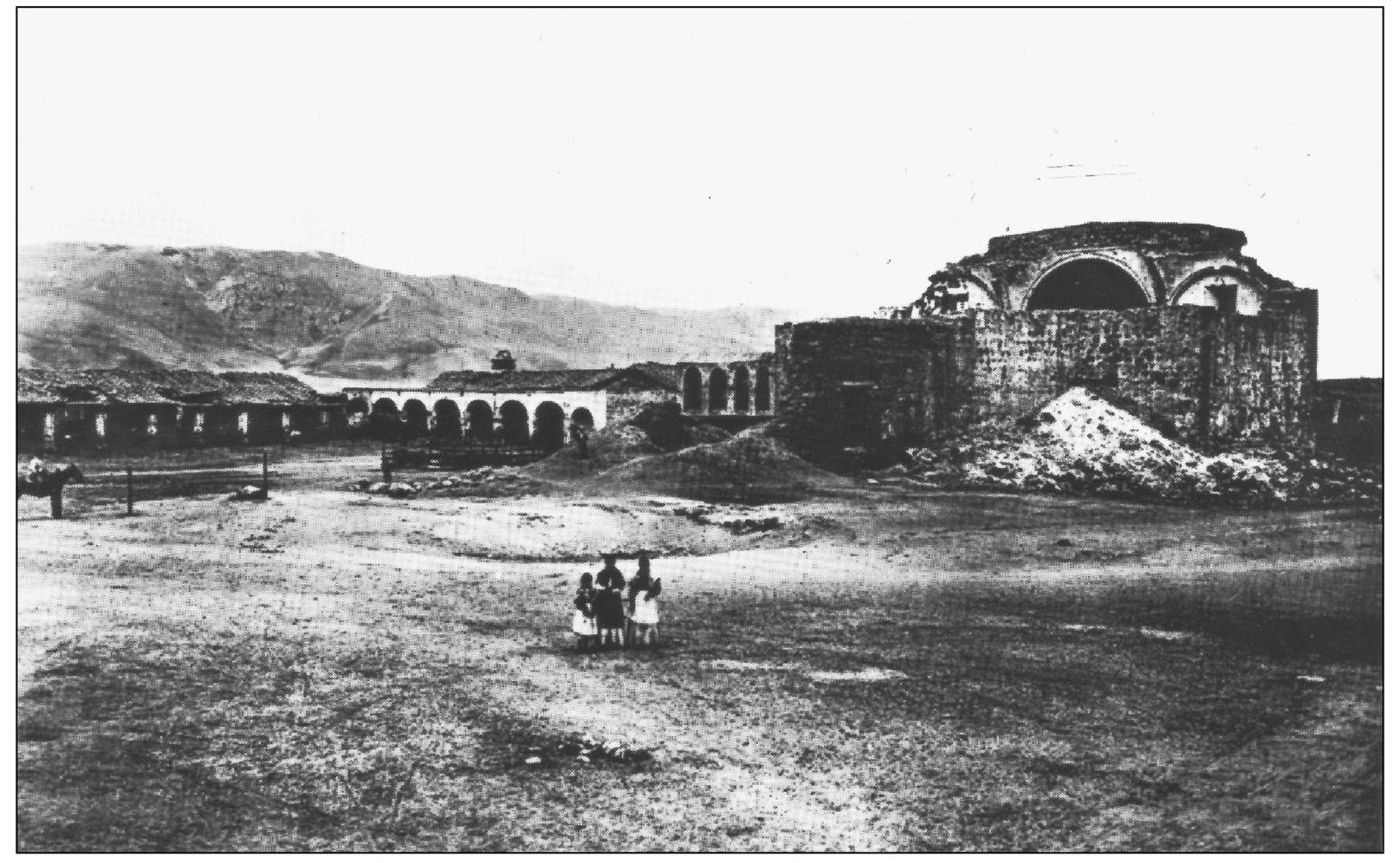

Henry Chapman Ford created this etching of the mission in 1883. The view looks east, showing a portion of an adobe wall that was built in a failed restoration attempt in the 1860s. Rubble from the earthquake of 1812 still appears in great mounds, and there is no landscaping except for a lone tree. The mission remained in this condition throughout the rancho period and its transition to diversified farming. (Courtesy Irvine Museum.)

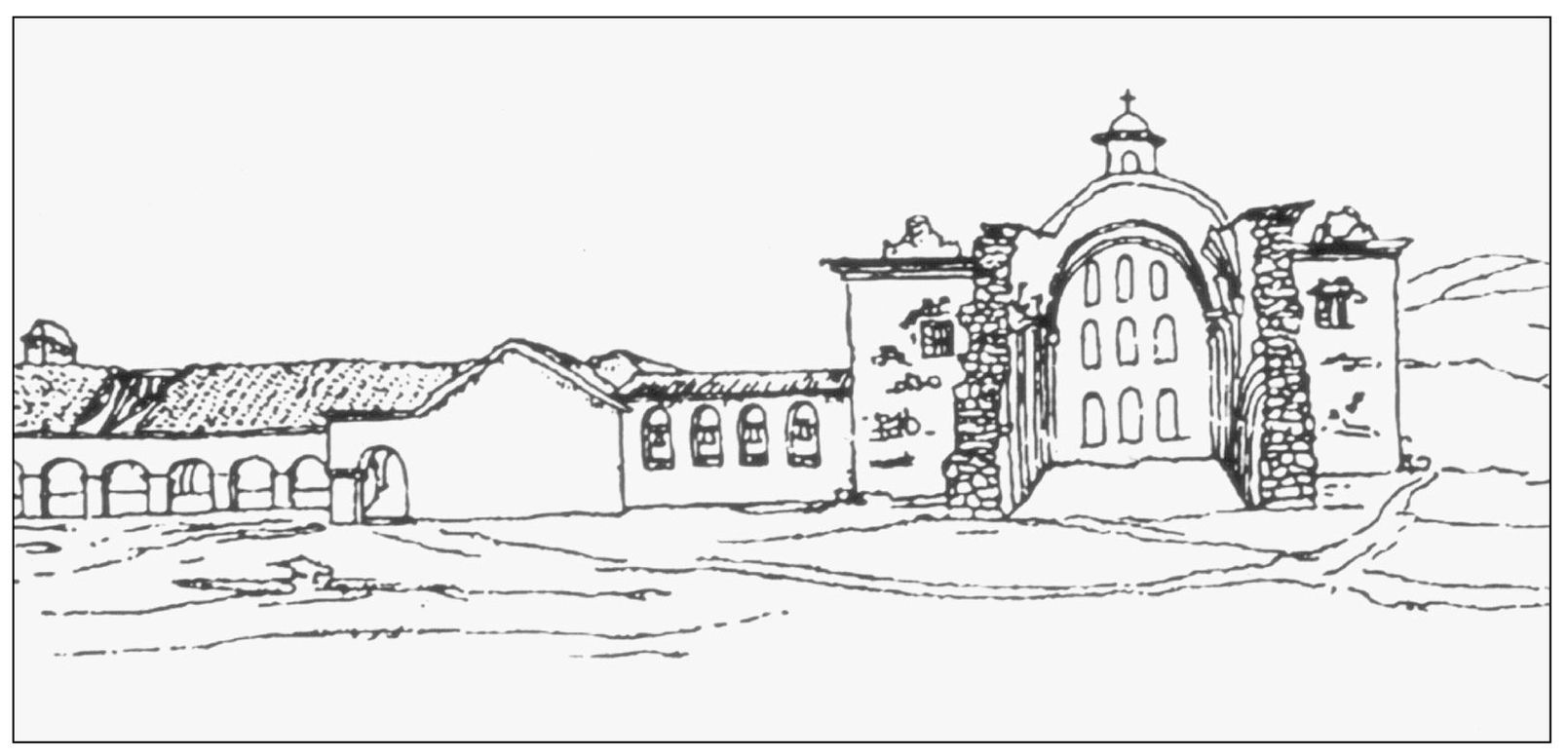

H. M. T. Powell drew one of the earliest sketches of the mission in March 1850. The head-on view does not include the mounds of rubble, thereby giving the mission a clean appearance. The remains of the church are clearly defined, including the cupola on top. The Forsters would have been in residence during this time period. (Courtesy Irvine Museum.)

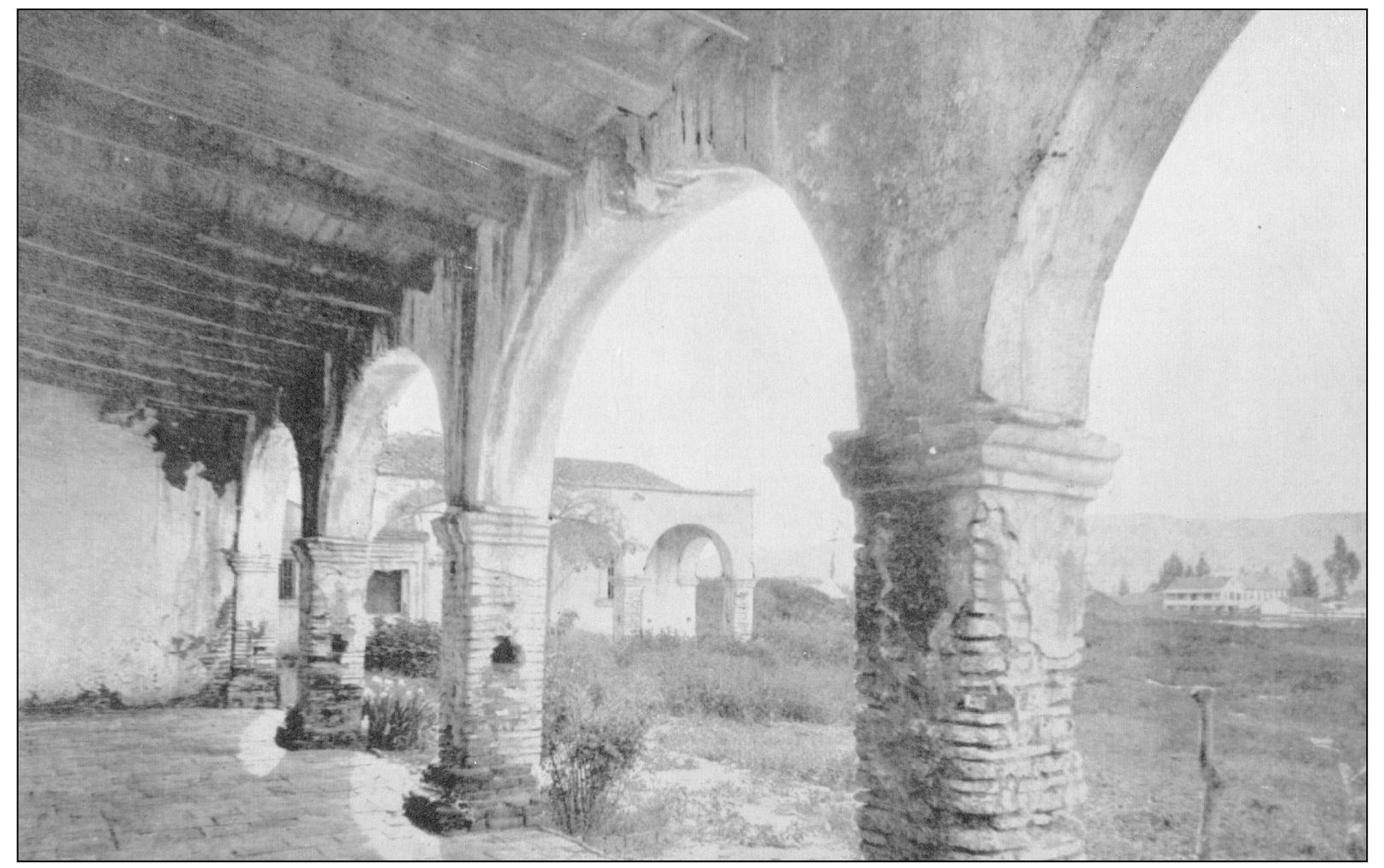

Carlton Watkins shot this early photograph of the mission in 1876. It is a view looking northwest and shows people from the village. Although officially abandoned during this time period, the property was owned by the Catholic Church, mass was said regularly in the Serra Chapel, and Fr. Jose Mut was in residence from 1866 to 1886. He also taught classes in one of the small rooms of the mission.

Amateur artist Edward Vischer visited San Juan Capistrano in 1865, and many of his images of the mission and its surroundings survive today. This drawing, dated May 9, 1865, shows the church ruins and the “ex-mission of San Juan Capistrano.” (Courtesy Irvine Museum.)

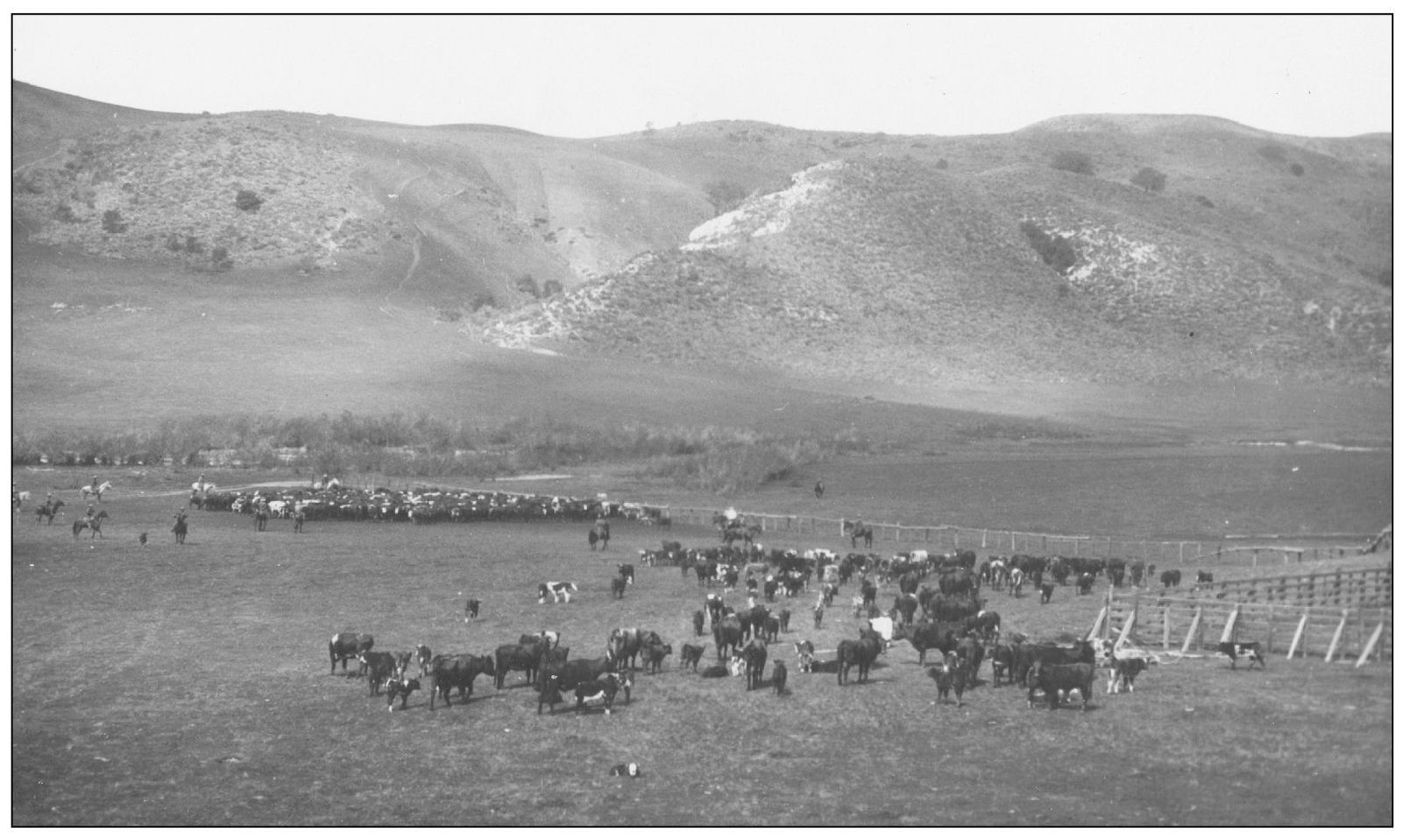

Cattle dotted the landscape of the great ranchos. The gold rush changed the nature of the cattle business, transitioning it away from hides and tallow to beef; herds were often driven all the way to San Francisco to feed miners and settlers. But 1862 brought with it a natural disaster that would bring further change—a drought that would decimate the herds. A smallpox epidemic also took the lives of a majority of the Indian workforce.

Bones of dead cattle littered the landscape at the height of the drought in 1864. Mired in debt and unable to pay taxes, many of the ranchos were sold, opening the way for a new social order based on diversified farming. As the rancho replaced the mission, now the farm replaced the rancho. Settlers looking for land at the end of the Civil War came to California. Only a few rancheros, like Juan Forster, were able to hang on and start over.

The influx of settlers from the United States changed life forever for the native Californios. Subjected to discrimination and hampered by a change of language to English, some turned to crime to survive. Tiburcio Vasquez, who engaged in hold-ups and rustling, was said to rendezvous with gang members in San Juan Capistrano under a large sycamore tree, reportedly used by many gangs, which still stands on Junipero Serra Road. While most of his activity was in Northern and Central California, he was known to commit crimes in the Los Angeles area as well. Popular with ladies and written up in the tabloids of the day, Vasquez was hanged for a murder he swore he did not commit (and others confessed to) on March 19, 1875.

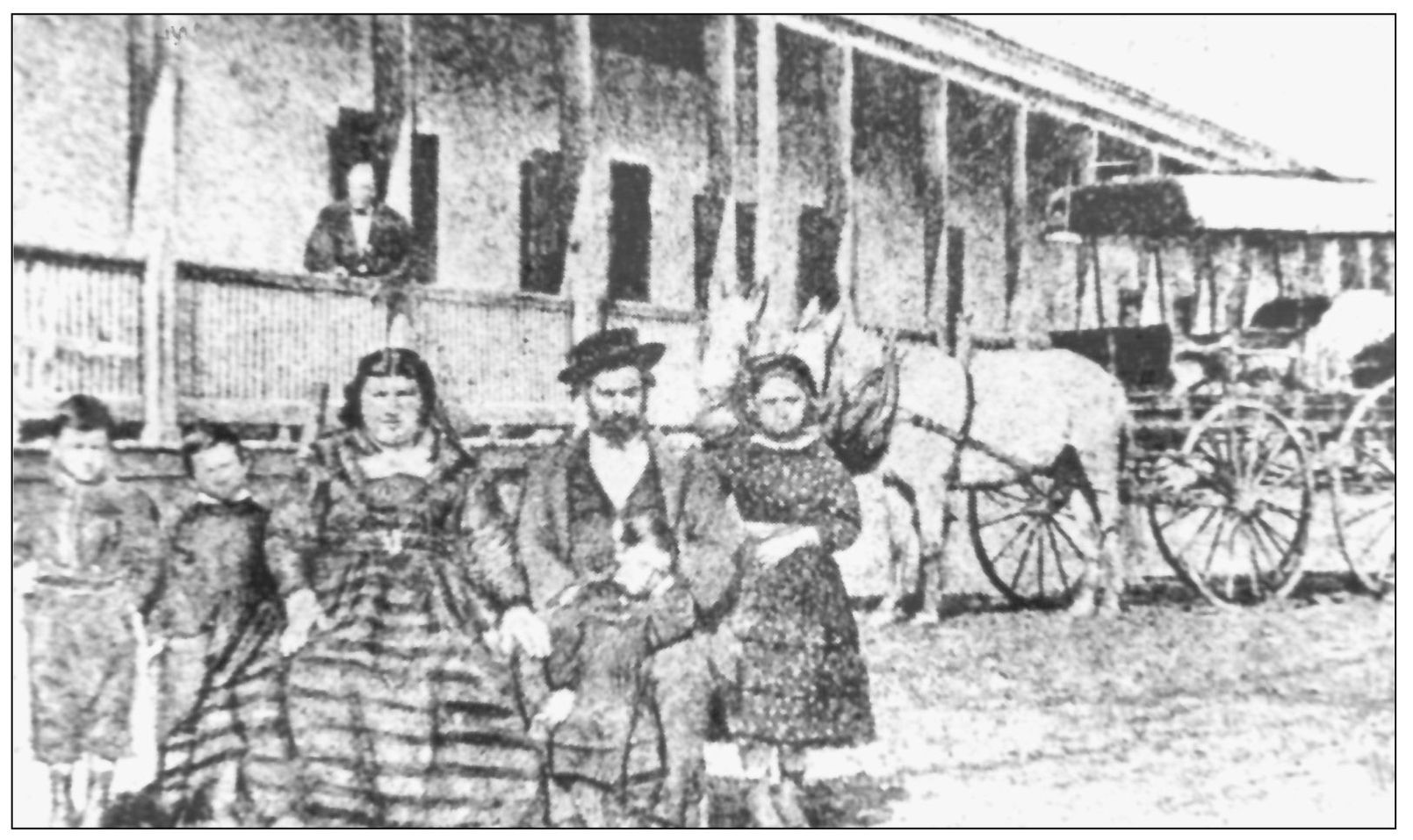

The Avila family poses outside their 10-room adobe home on the west side of the old plaza in San Juan Capistrano, on what is today Camino Capistrano. Juan Avila is said to be the one on the porch. The adobe was partially destroyed in a fire in 1879, and only the southerly portion was rebuilt. The family continued to reside in small quarters until Avila’s death in 1889.

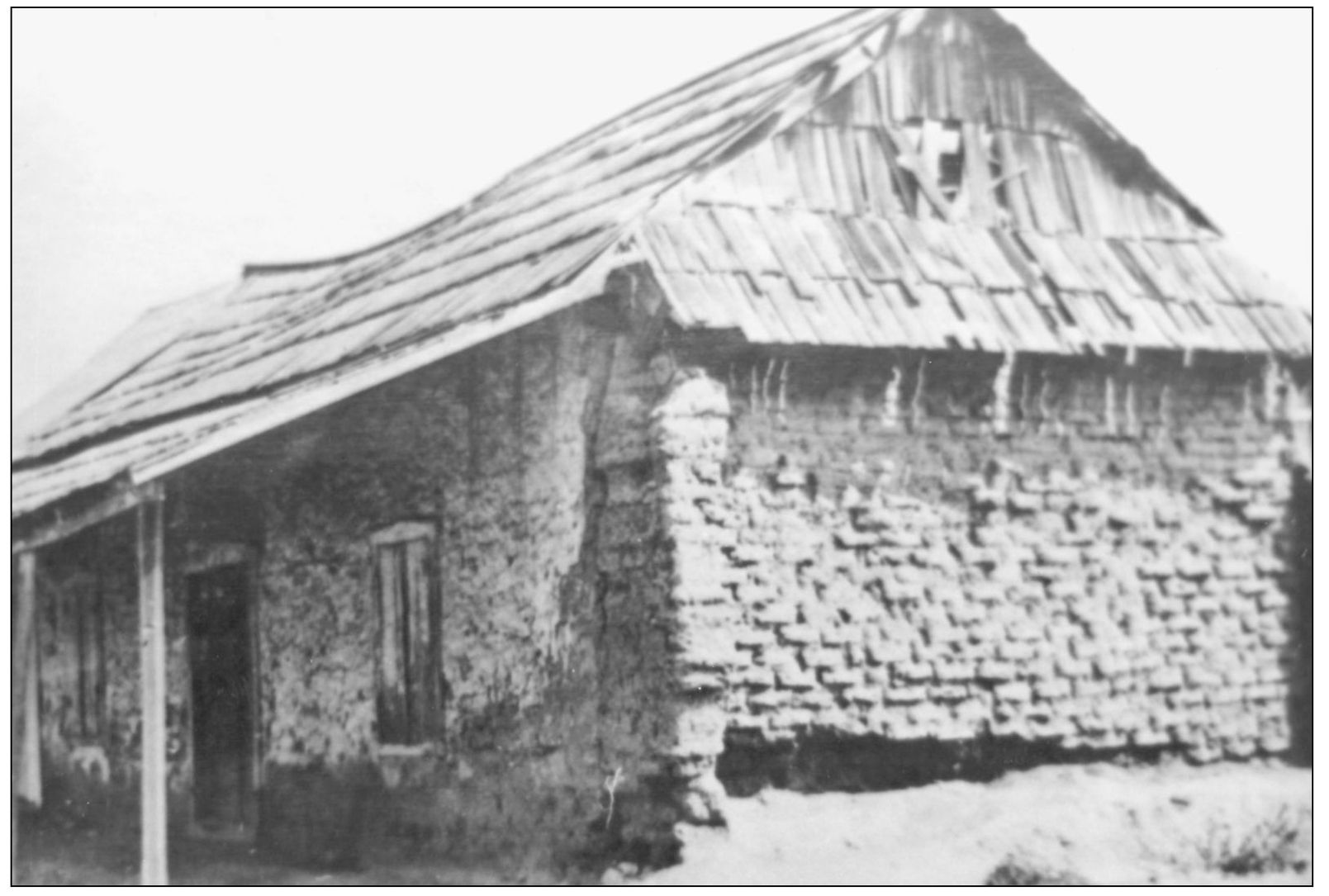

The Canedo Adobe, which once stood on the corner of Ortega Highway and El Camino Real where a parking lot is today, was believed to be one of the original adobes of the mission. It is best known for Salvador Canedo, who occupied it in the 1850s and whose death was the last to be recorded in the Death Register as a victim of smallpox.

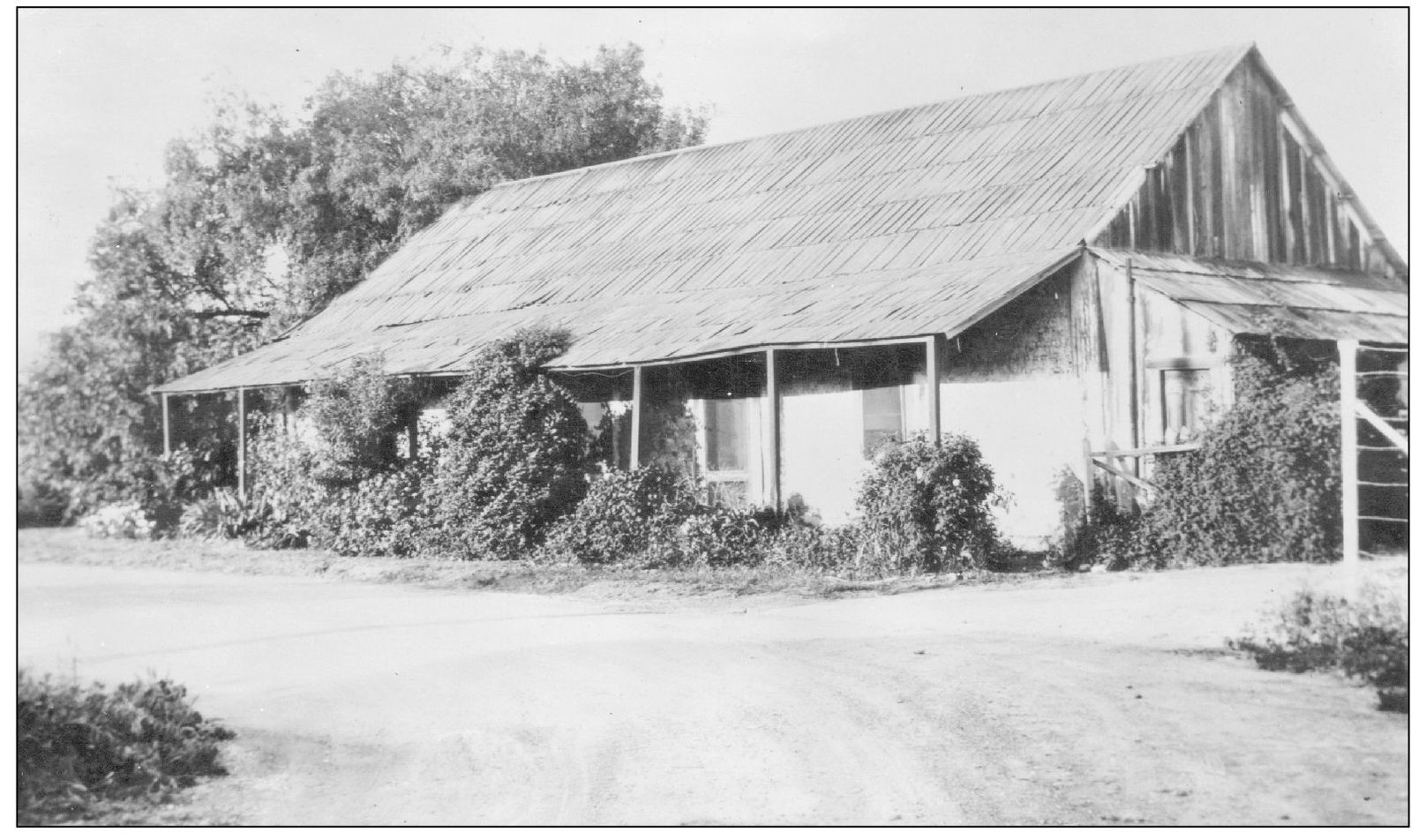

The Burruel Adobe once stood on the east side of the plaza at the south end of El Camino Real. In the 1850s, it was the home of Tomas Burruel and his wife (then housekeeper), Martina, who had an infamous past. The adobe eventually passed to the Hunn family, but fell into disrepair and was demolished by wind and rain. Nothing is left of it today.

The Garcia Adobe, the only two-story Monterey-style adobe remaining in San Juan Capistrano, was the location of a famous robbery and murder of merchant George Pflugardt in 1857. Changing hands, the building became the French Hotel, then the Oyharzabal General Store. It also served briefly as the post office. It is still standing today with residential spaces above and retail stores below in downtown San Juan Capistrano.

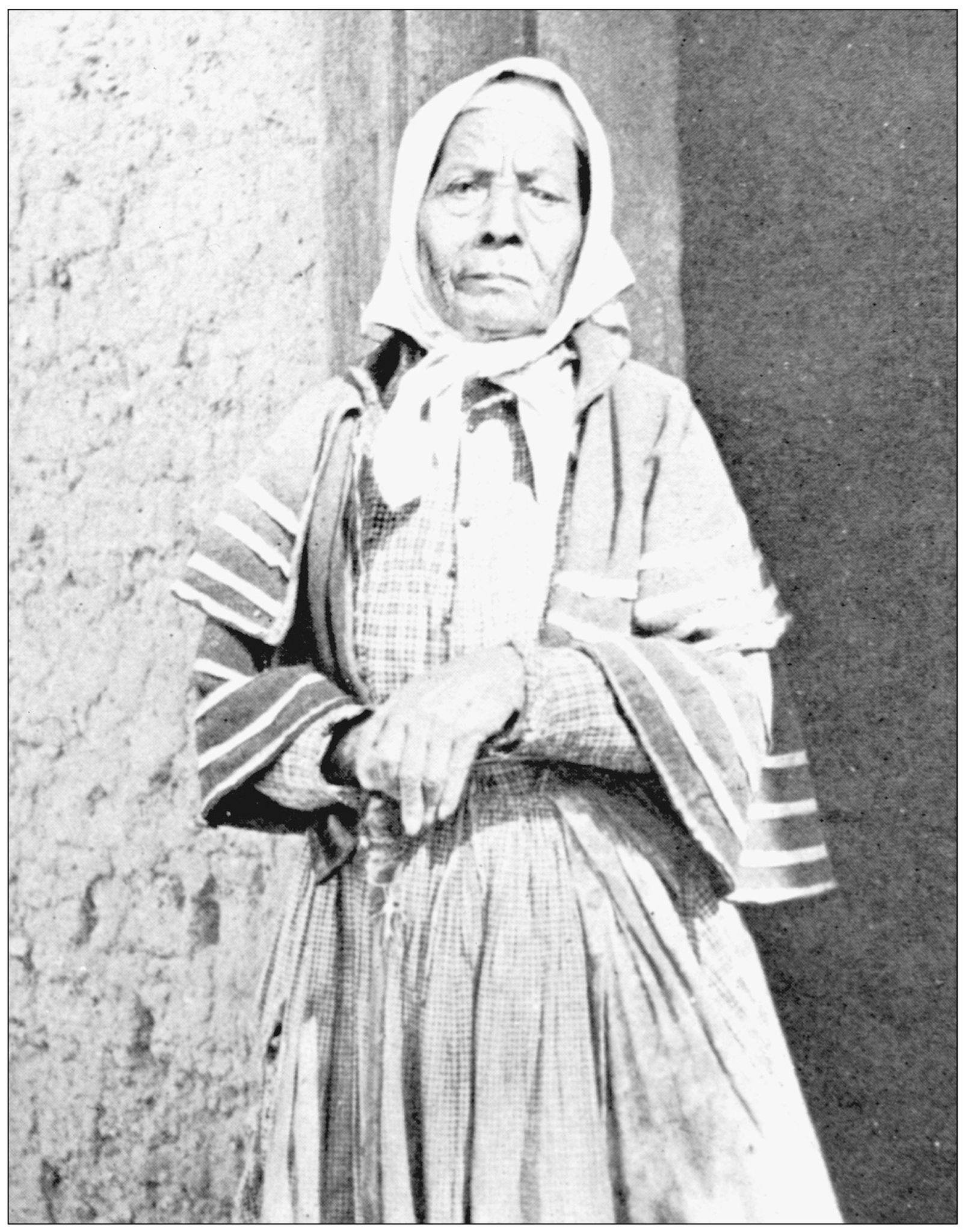

Martina Burruel, nicknamed “Chola Martina,” was the sweetheart of the bandit Juan Flores in her youth. She is said to have visited merchant George Pflugardt after dark, and while he was finding a garment she had pawned, she slipped into the doorway of the Garcia Adobe and lit a cheroot, signaling the bandits, who robbed the store and murdered the merchant. A manhunt ensued that resulted in an ambush of Sheriff James Barton and his posse, coming from Los Angeles to track down the criminals. Flores was eventually caught and hanged at public execution. Martina, a housekeeper who married shoemaker Tomas Burruel and was never prosecuted, lived a long life and posed for many pictures.

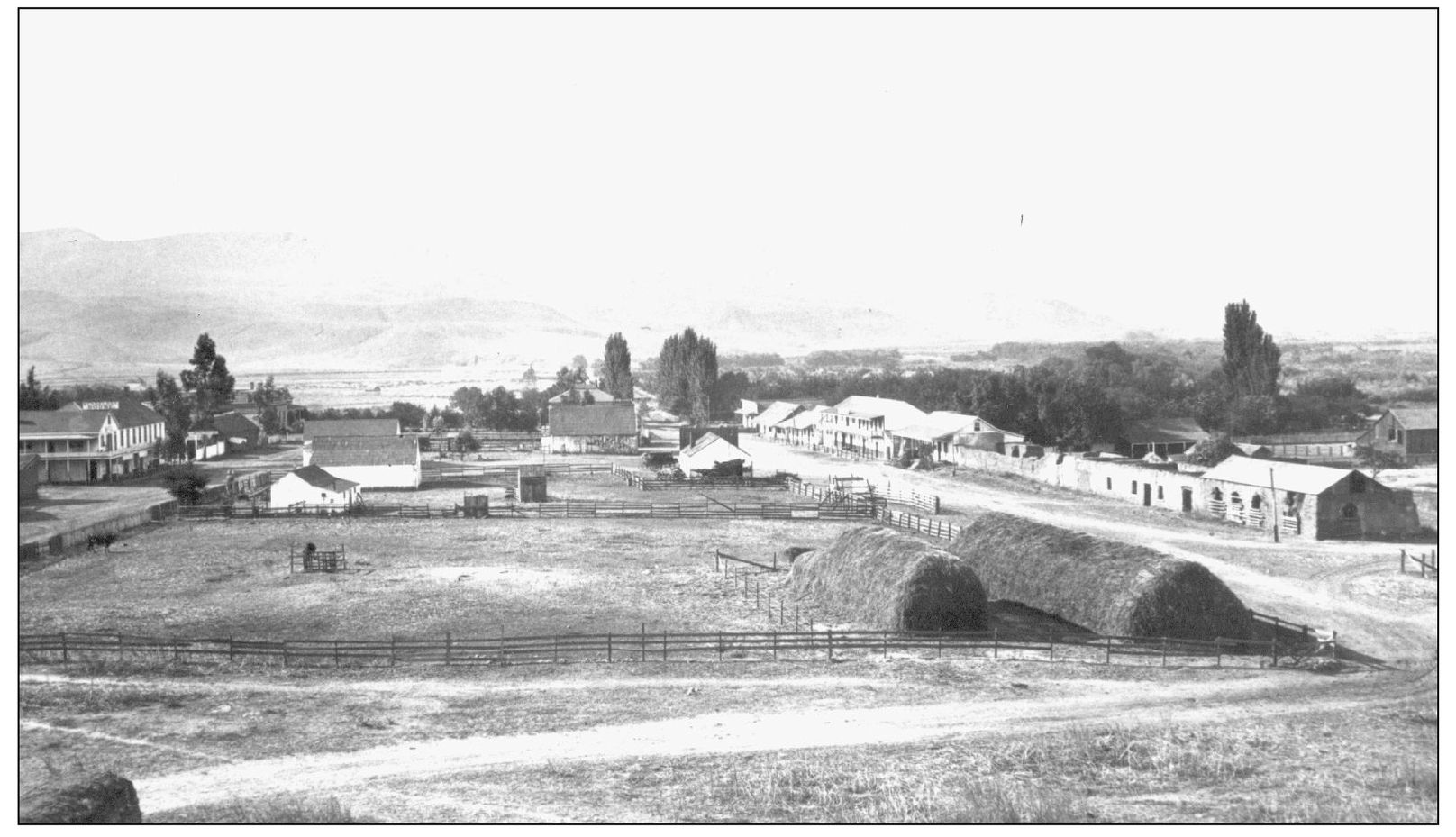

This is a view of the town to the south from the mission roof, as it looked in the 1880s. El Camino Real is the street on the left, and Camino Capistrano the street on the right. The buildings on both sides face into the plaza, the fenced area. A few buildings appear on the southern portions of the plaza, something that did not take place until after the first town map was filed in 1875, showing the plaza divided into lots.

The mission in the 1880s was starting to be noticed. Considered by many a source of building materials for new construction and tiles for roofs, it began to lose some of the buildings that had withstood time and adversity. Because of structural weaknesses, church services were moved in 1891 to the sala, a front building which the Forsters had once occupied. After Fr. Jose Mut’s departure in 1886, there would be no priests in residence for 24 years.

Droughts, American land policies, the decline in beef prices, and other calamities forced the break up of many ranchos. The Land Acts of 1851 required each grantee of land to defend his title in a court of law, usually in San Francisco. Sometimes the cases dragged on for years, creating debts for the landowner. Some cut their losses and sold to farmers. The Capistrano Valley was a fertile area for wheat, barley, beans, corn, and English walnuts in the 1870s and 1880s. Felipe Garcia, second from right, takes a break with other hay balers on one of the local farms in 1875. Farming would continue to be viable for almost another century.

Henry George Rosenbaum homesteaded government land three miles north of the mission in 1869. The property was located on both sides of the El Camino Real and Oso Creek between Rancho Niguel and Rancho Mission Viejo. He became a rancher, as did his sons and grandsons after him. Previously, he lived in San Francisco where he was the builder of the first Cliff House above Seal Rocks.

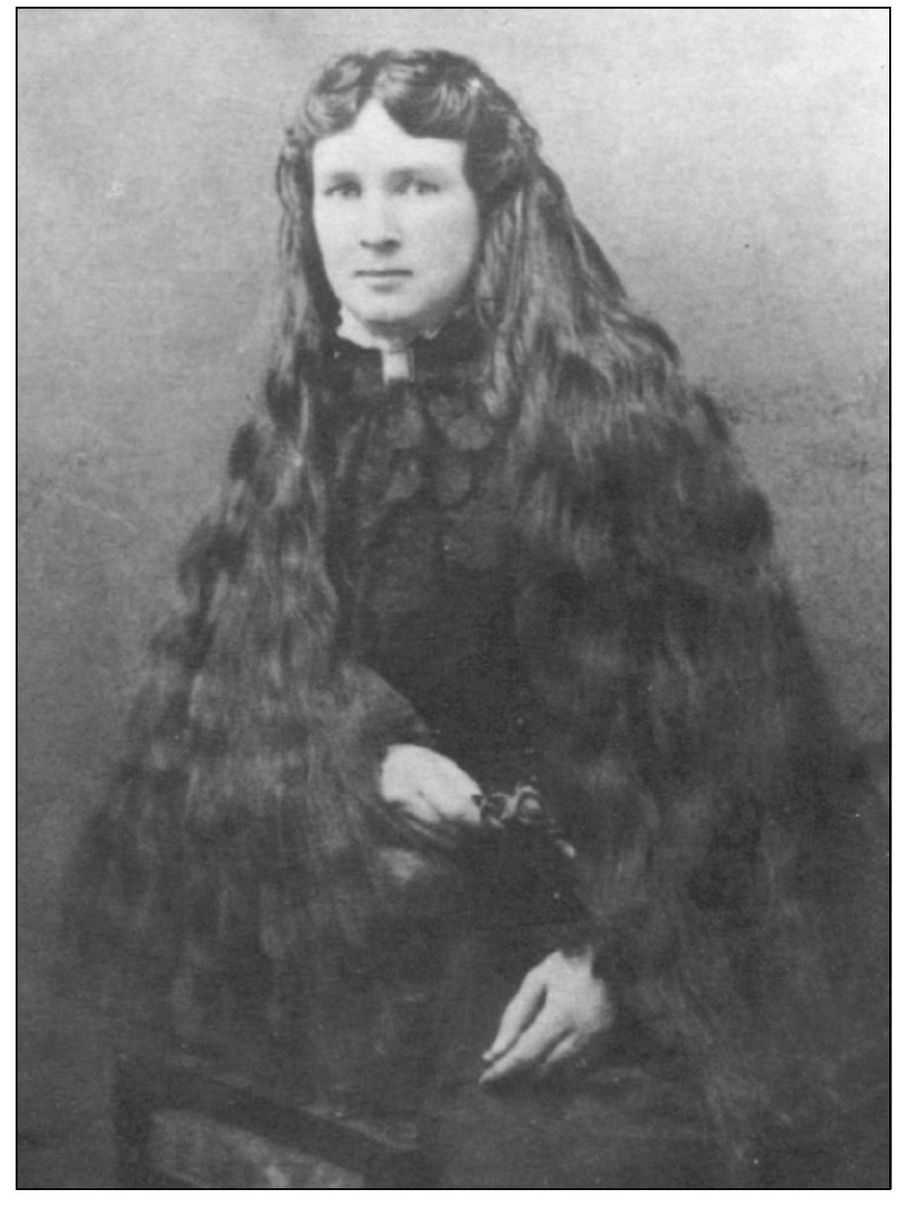

Molly Sheehan Ronan was a very young woman in 1869. Her father was James Sheehan, who settled on land east of the mission near where the Mission Cemetery is today. There is a story that a young Richard Egan, later a judge, was enamored of Molly, but never told her of his interest. She eventually left the area and married someone else, telegraphing the news to her friends in San Juan. Egan, also the local telegrapher, was the first to receive the message.

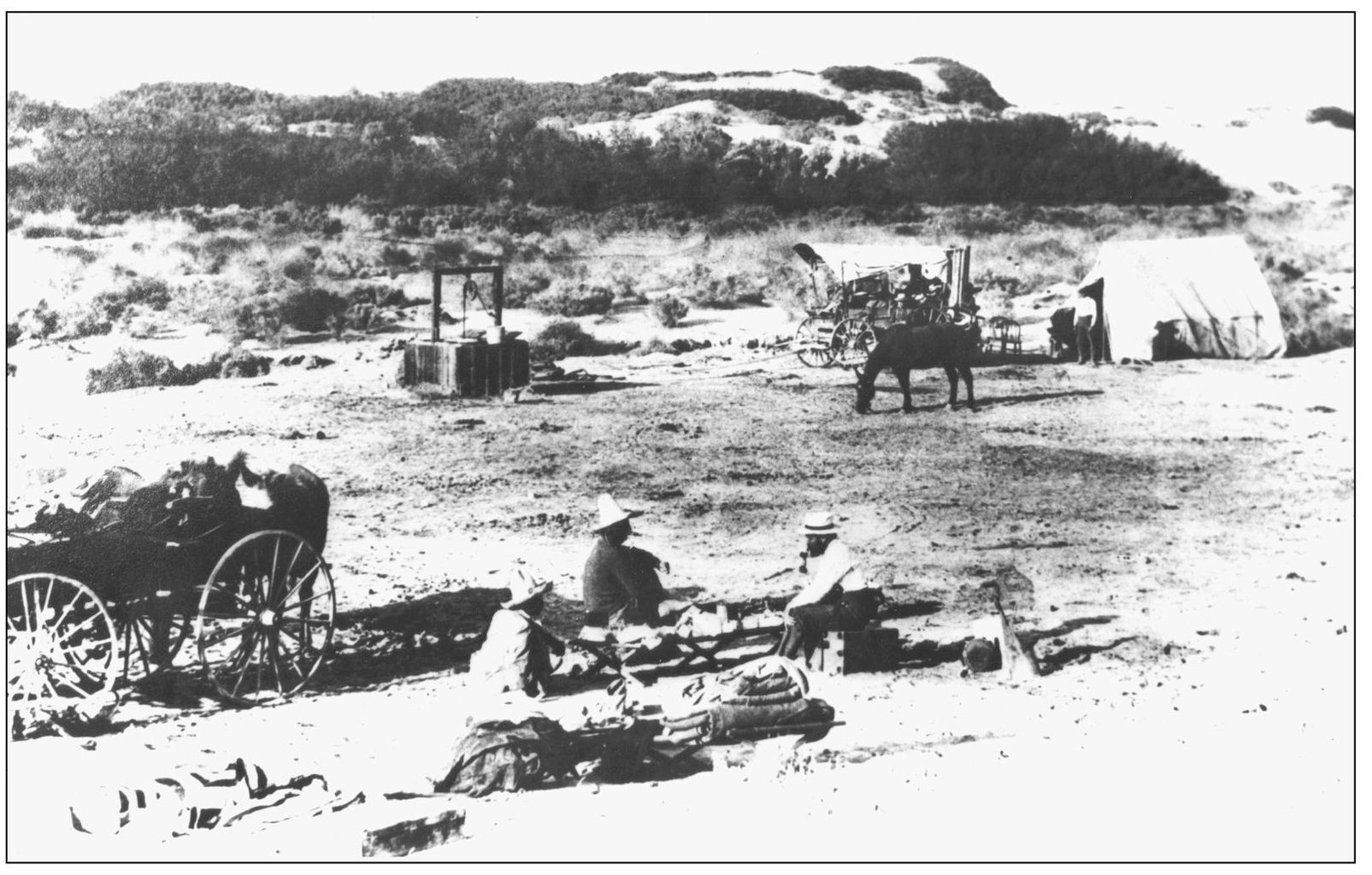

Not all the ranchos disappeared. Juan Forster’s landholdings were sold by his heirs in 1882 to Richard O’Neill and James Flood, both of San Francisco. These ranches were again split and some of O’Neill’s heirs acquired the lands in Orange County and the others, along with Flood’s heirs, took the San Diego properties. The O’Neill Ranch continued to own cattle. Pictured is one of the camps used during roundups.

The building with the fence served as the mission chapel from 1891 until the mid-1920s. It also housed the Forsters when they were in residence in the years prior to restoration of the property to the Catholic Church. Although this photograph is believed to have been taken by Carlton Watkins in 1876, nothing changed on the mission grounds until the Landmarks Club of Los Angeles began their structural work in 1895.

This view of Camino Capistrano in the 1880s shows the two-story Garcia Adobe as the French Hotel. It was built by Manuel Garcia in 1841, and was infamous in 1857 as the place where Juan Flores murdered shopkeeper George Pflugardt. The building was sold in the 1880s to the Oyharzabal family, who opened the French Hotel and operated it until 1903 before opening a general store. It is the only two-story, Monterey-style adobe in town.

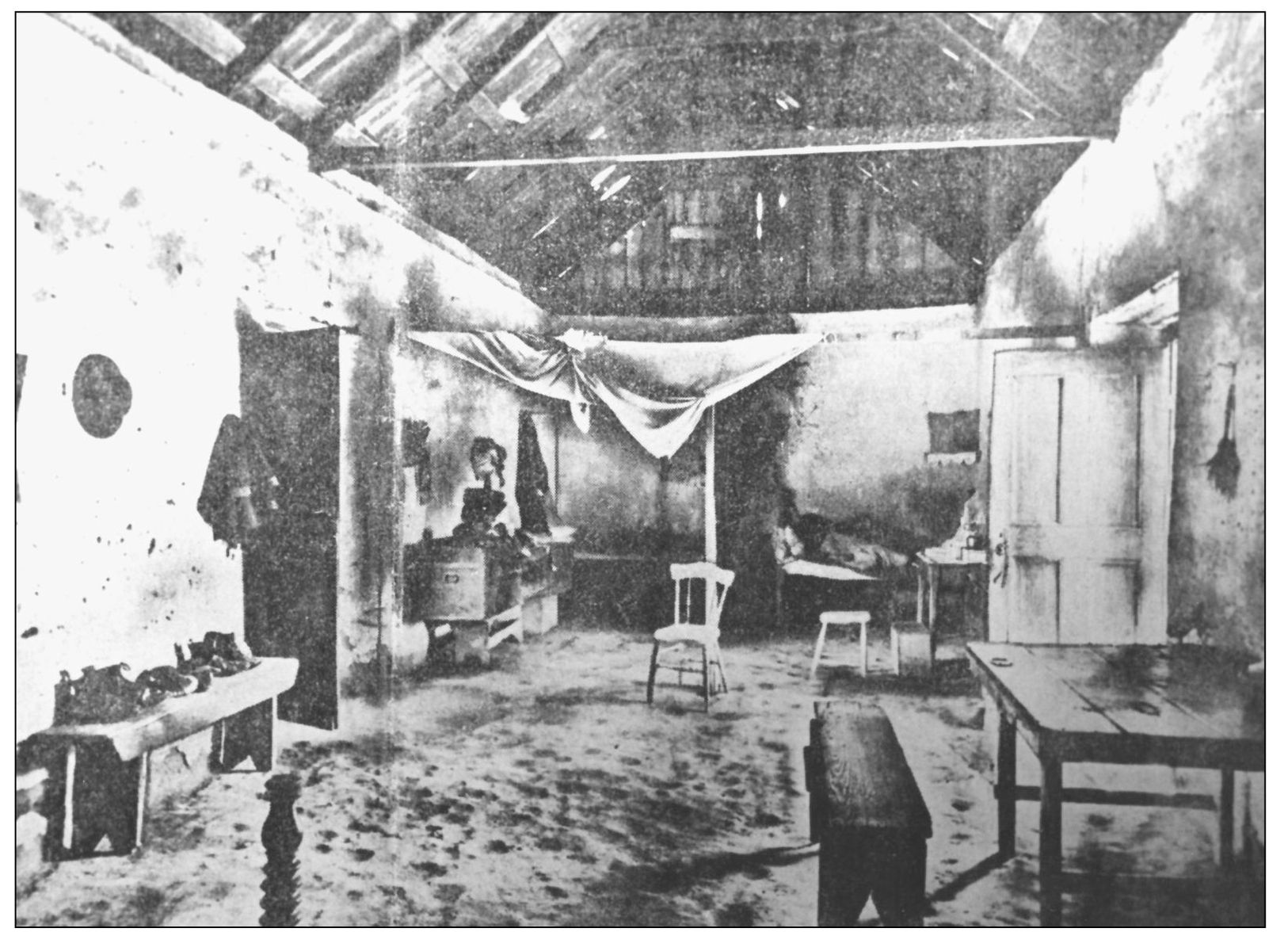

This is the interior of the Burruel Adobe, occupied by “Chola” Martina Burruel, who was once the sweetheart of the bandit Juan Flores. It is a typical adobe with a dirt floor, simple wood furnishings, and thick walls. Believed to be one of the “little cabins” of the early mission period, the building no longer exists. She died in 1910.

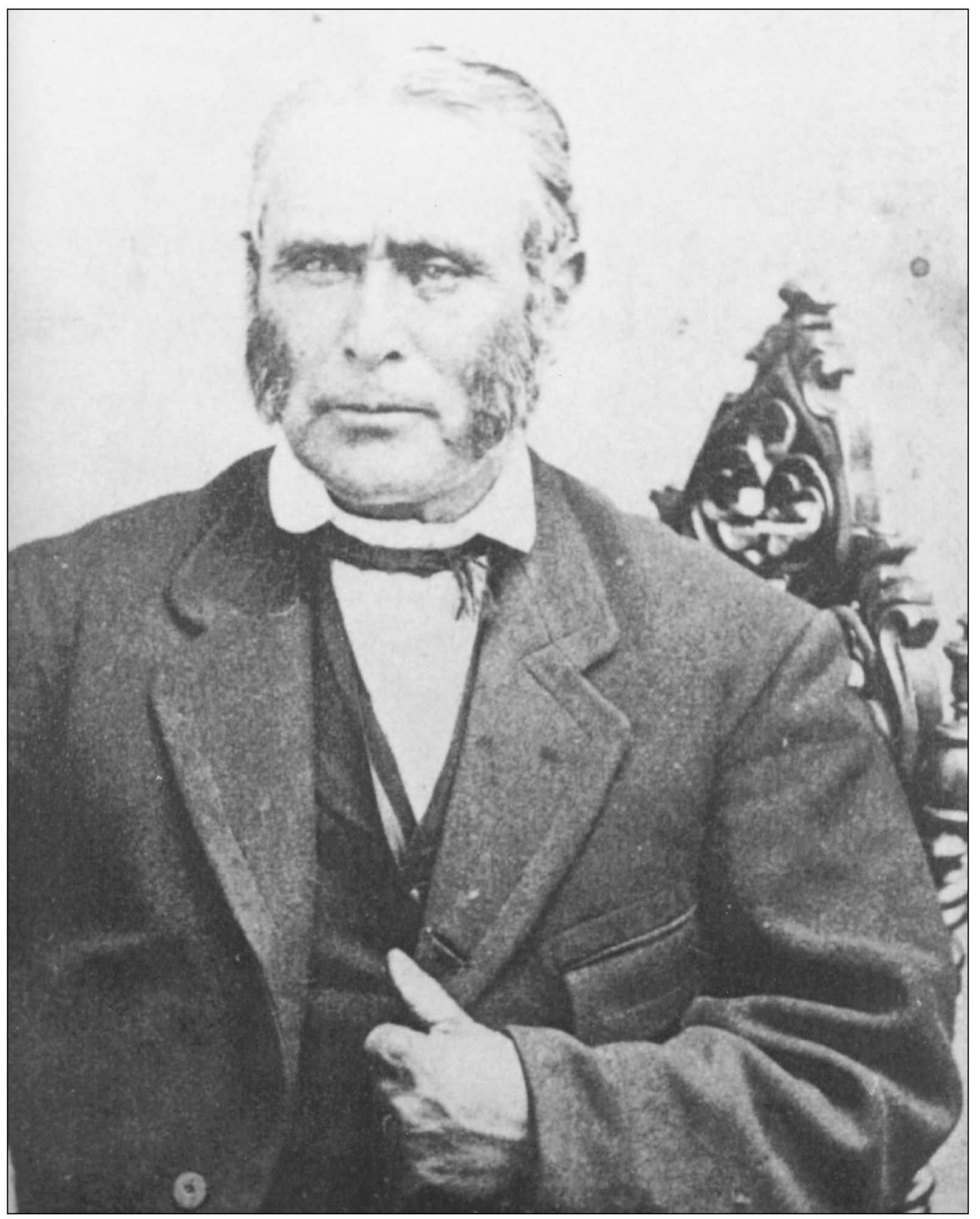

Juan Avila, in his old age, was a pillar of the community. He served on the first board of San Juan School, one of three schools started in 1850 in what was then Los Angeles County. He was widely known as a gracious host, housing such visitors as Judge Benjamin Hayes, historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, Gen. Stephen A. Kearny, and Col. John C. Fremont. He and his wife, Soledad Yorba de Avila (married in 1833), had three children who survived to adulthood: Rosa Modesta, who married Pablo Pryor; Guadalupe, who married Marcos Forster; and Manuel Donanciano “Chano,” who married Delfina Rodriquez. Soledad died of smallpox in 1867. Juan survived his wife by 21 years and was cared for by his daughter, Rosa, who lived with Juan in the adobe on Camino Capistrano after the tragic death of her husband.