Five

CHASING RAINBOWS

1910–1930

San Juan Capistrano was a thriving agricultural community in 1910 and was about to get electricity, telephones, a modern school, and its first paved street. Adobes interspersed with wooden structures dotted the downtown area, and in 1919 its first Protestant church opened.

The mission flourished under the guidance of Father O’Sullivan, who had a knack for involving people in his many projects. O’Sullivan fenced the mission and started charging an entrance fee. He also wrote a book as a fund-raiser and arranged for a pageant to be produced on mission grounds. His most prominent project was the restoration of the Serra Chapel and the inclusion of a gilded cherry-wood altar, originally destined for a cathedral. Capital improvements in the 1920s included an adobe wall that replaced the mission’s picket fence and provided additional security, and the construction of a new Mission School.

During World War I, people flew flags on their homes and sent their sons to the war effort, but largely remained unaffected. Prosperity was manifested by the new brick hotel, a number of restaurants, and several new stores. Most popular with the younger set was a movie house. Several movies had been filmed in the mission, sustaining interest in this California industry.

In 1919, the Capistrano Union High School District was formed, opening its first school in 1920 on the highway north of the mission. It would serve several elementary schools in the valley. Oranges were catching walnuts as the area’s most prominent crop, and avocados were also abundant. Reporting these changes was the Coastline Dispatch, a weekly newspaper that started as the Missionite, the high school paper.

Tom Forster, at left, is seen with his crew in White’s Garage, which was located in downtown San Juan Capistrano. Marco F. “Tom” Forster was the son of Frank, grandson of Marcos, and great-grandson of Juan Forster. He opened the White Garage in the 1920s, but soon went back to his first love, ranching and dry-farming. He served as justice of the peace from 1938 to 1953 and was nicknamed, “Mr. San Juan Capistrano” because of his generosity and hospitality. The advent of the automobile lured many into exploring automobile-related businesses. Two or three garages opened in downtown and were largely successful.

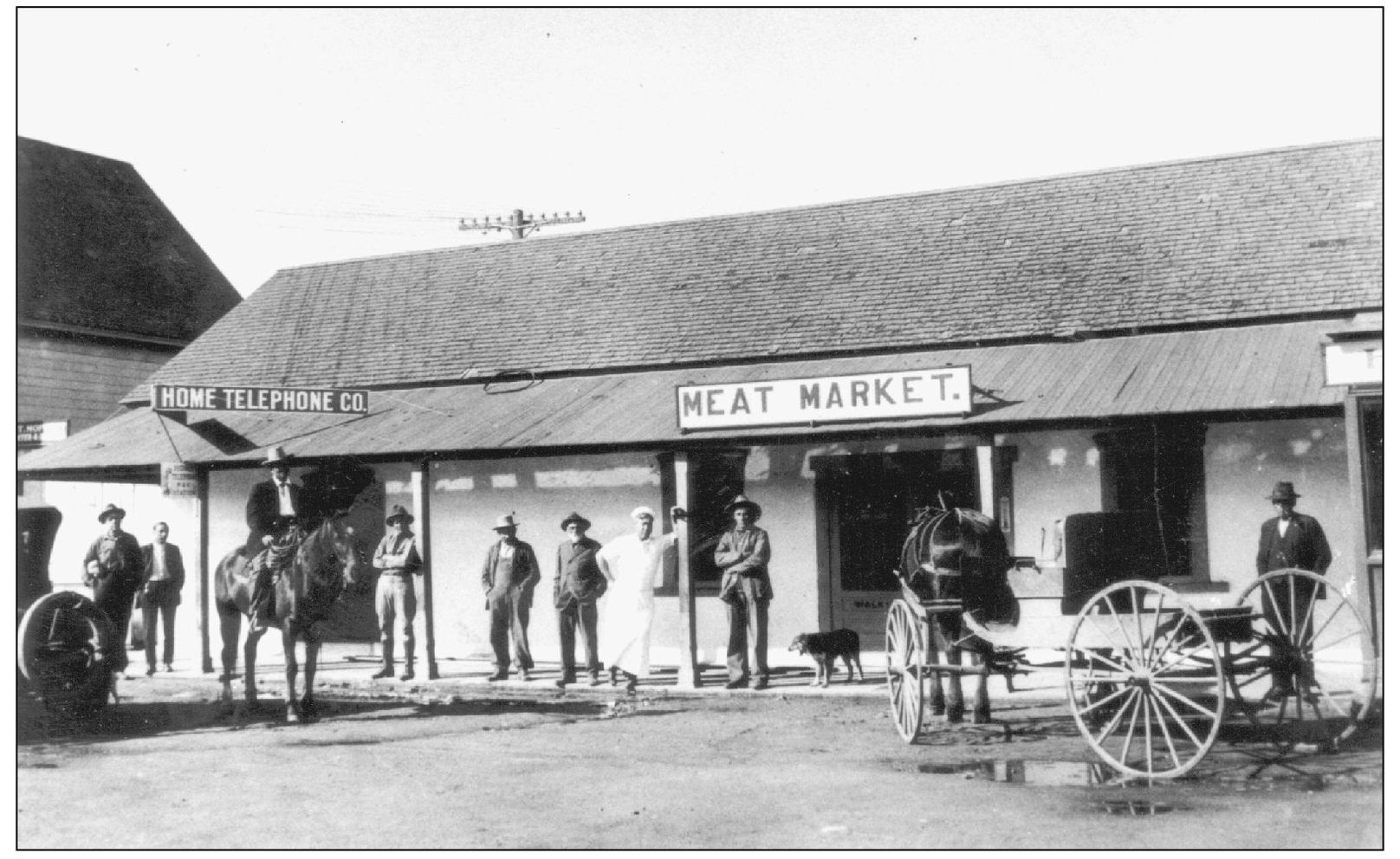

Labat’s Meat Market and the Home Telephone Company occupied part of what is thought to have been the Avila Adobe, which was rebuilt after the fire of 1879 a block south of the mission. Telephone service came into being around 1917, and the first operator was Fidel Sepulveda. The market was there a few years earlier.

The Shell station was one of the earliest gas stations in town. It was located on the west side of the mission, along the newly extended Camino Capistrano, about where Mission Hacienda Plaza is today. The state highway was pushed through around 1915, and several gas stations were erected along the road during the next five years.

The Standard Oil Company also built a gas station along the new state highway through town, opening for business on July 1, 1918. Located on the east side of the mission and south of the Shell Station, the oil company purchased excess land from the diocese in December 1917—land that had been cut off from the body of the mission when Highway 101 went through in 1915.

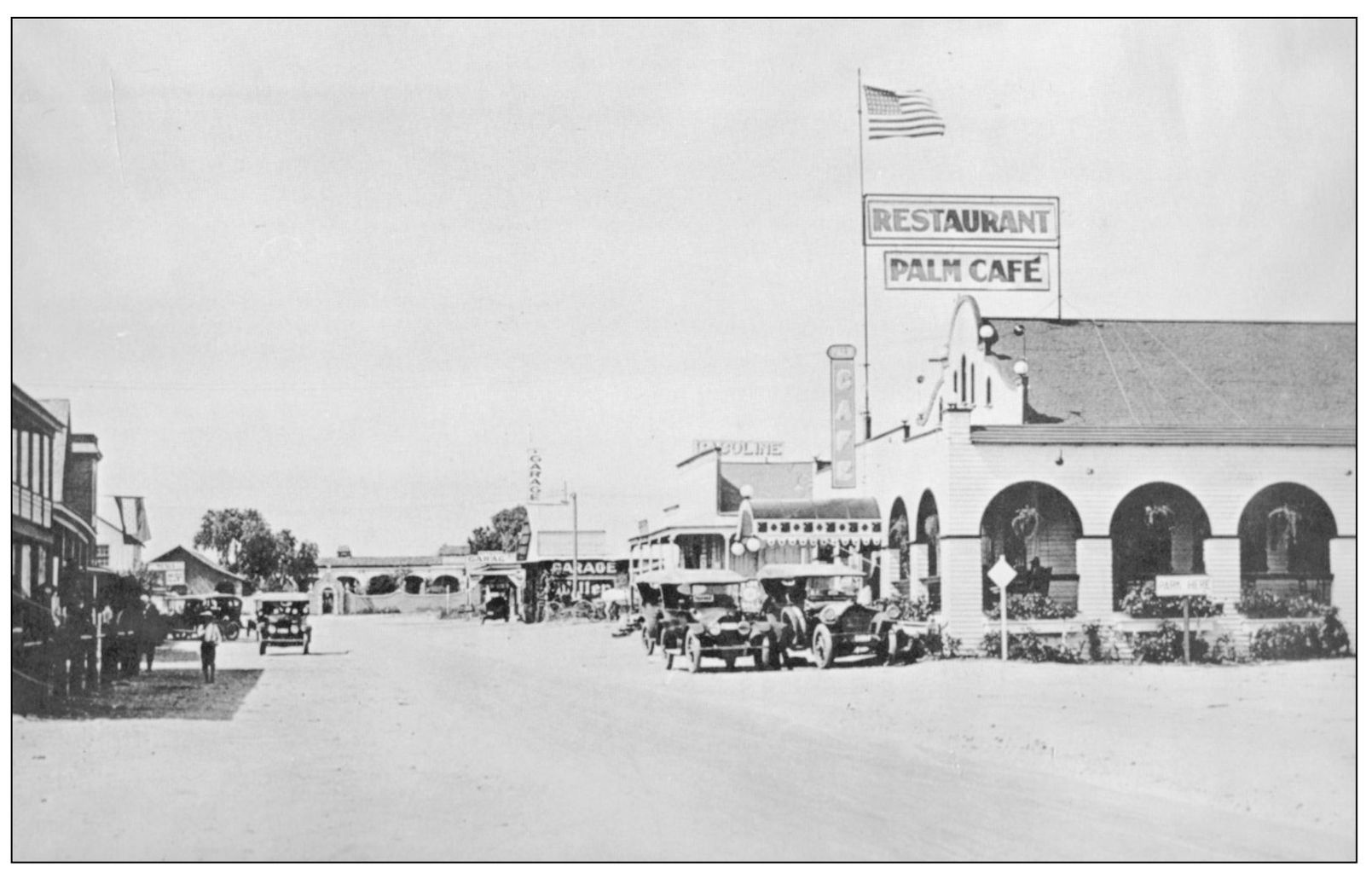

A touring car parks in front of the Palm Café. The 1870s building once housed San Juan Grammar School, which was relocated downtown and converted into a restaurant around 1912. It originally had a tower with a school bell, which was removed prior to the restaurant opening.

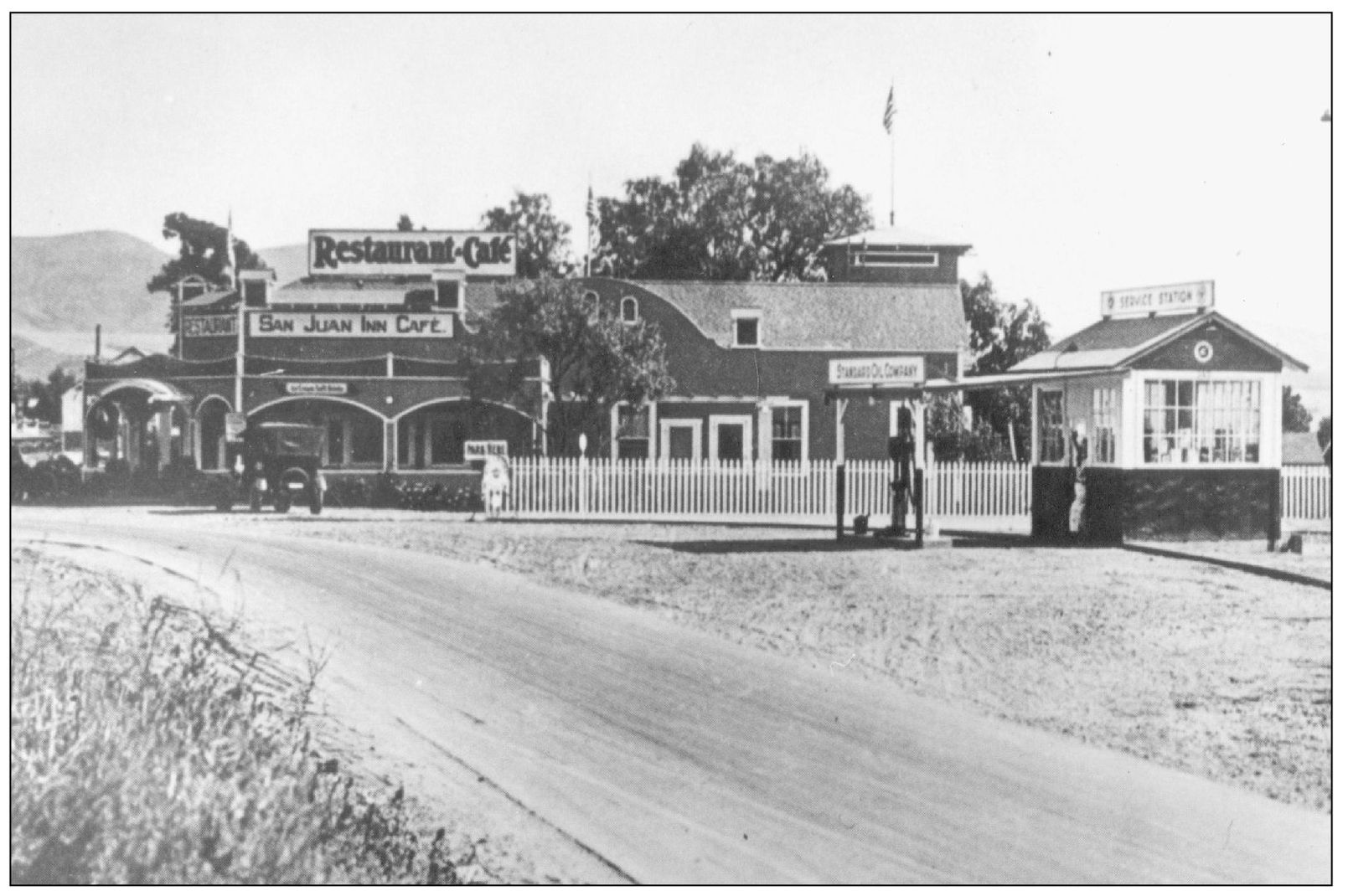

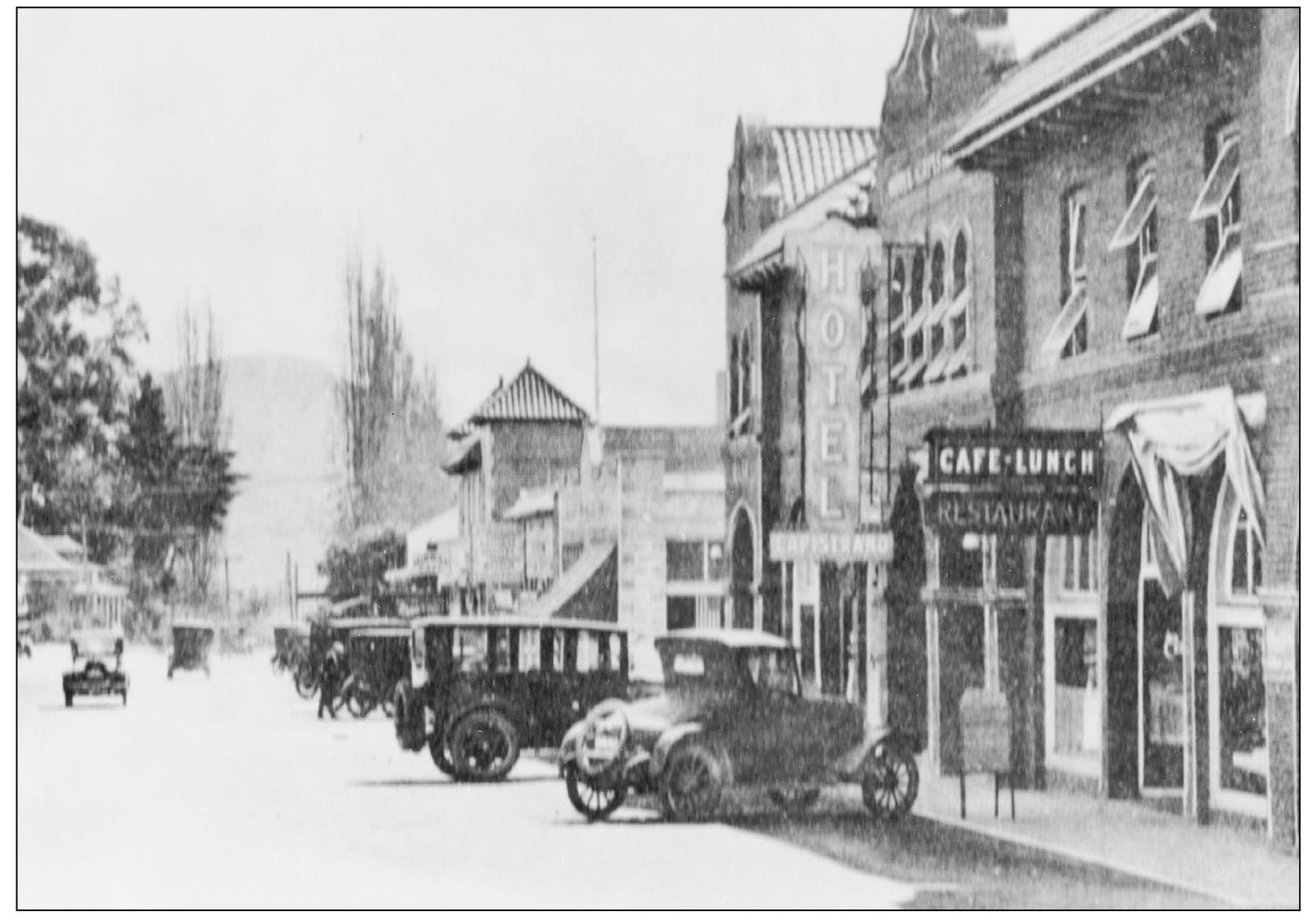

Fred Stoffel, standing, greets guests at the San Juan Inn, located across from the mission entrance about where the Trading Post is today. Capistrano was a popular destination for travelers, as it was halfway between San Diego and Los Angeles and offered many fine accommodations.

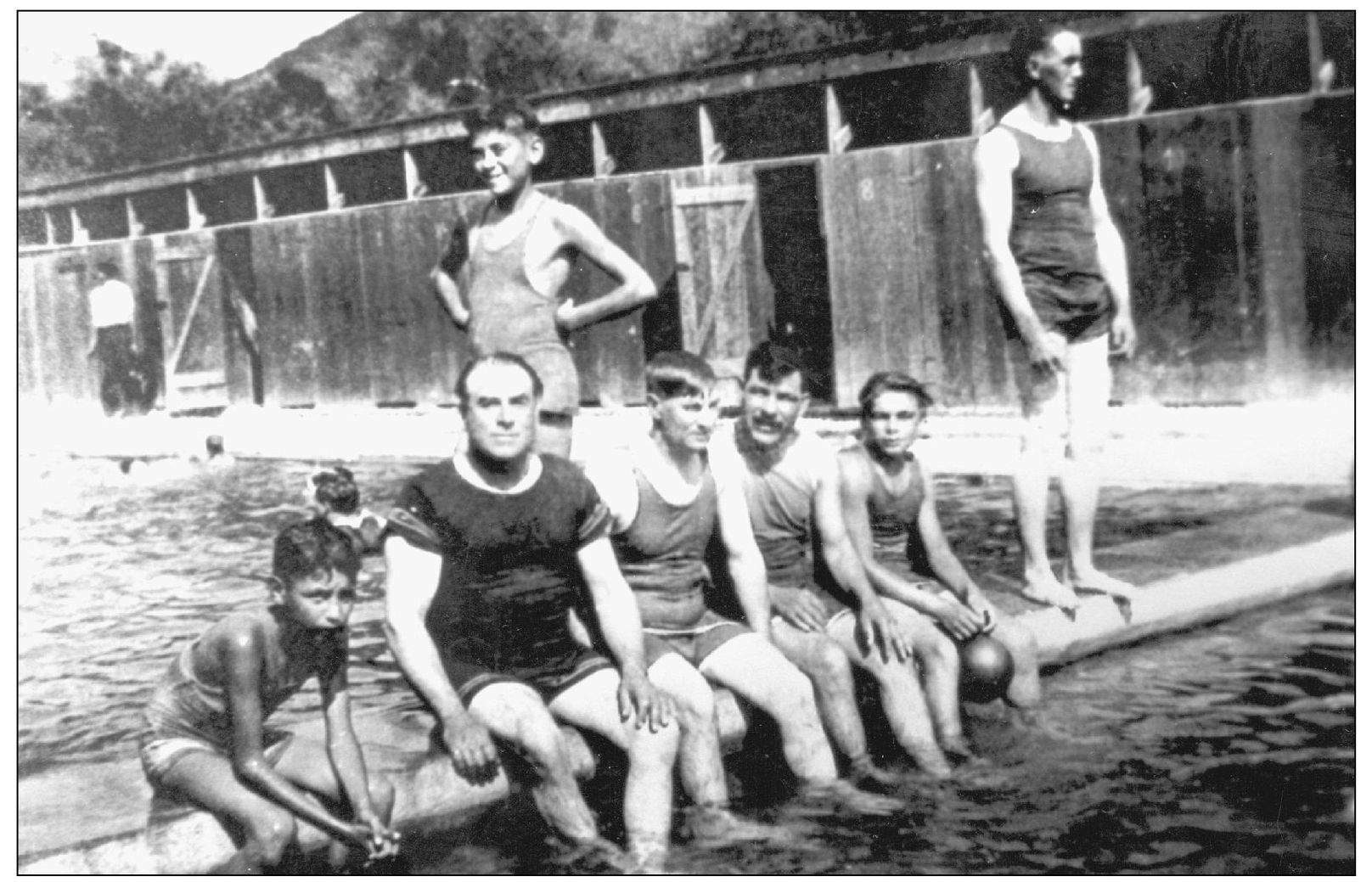

One of the most popular tourist destinations in the 1920s was still the San Juan Hot Springs. During the 1920s the operator was Leon Eyraud, who made improvements and advertised it as a recreational area as well as a health resort. Swimmers gather in the swimming pool located next to Ortega Highway. Ruins of it can be seen today.

The Capistrano Hill Climb was a famous and grueling motorcycle race that was held from 1916 until about 1924. It was located on a hill on the east side of what is today Interstate 5 where it makes a curve inland at the Capistrano Beach off-ramp. At the time, the community was called Serra and the hill was a 500-foot, 72-degree dirt slope. It was one of the largest cycling events on the West Coast, sometimes playing to crowds as large as 30,000. When the event ended, it was to protect the cattle and dairy industry from the spread of hoof and mouth disease, which was at an epidemic stage. The race was never revived, and today the hill is much altered.

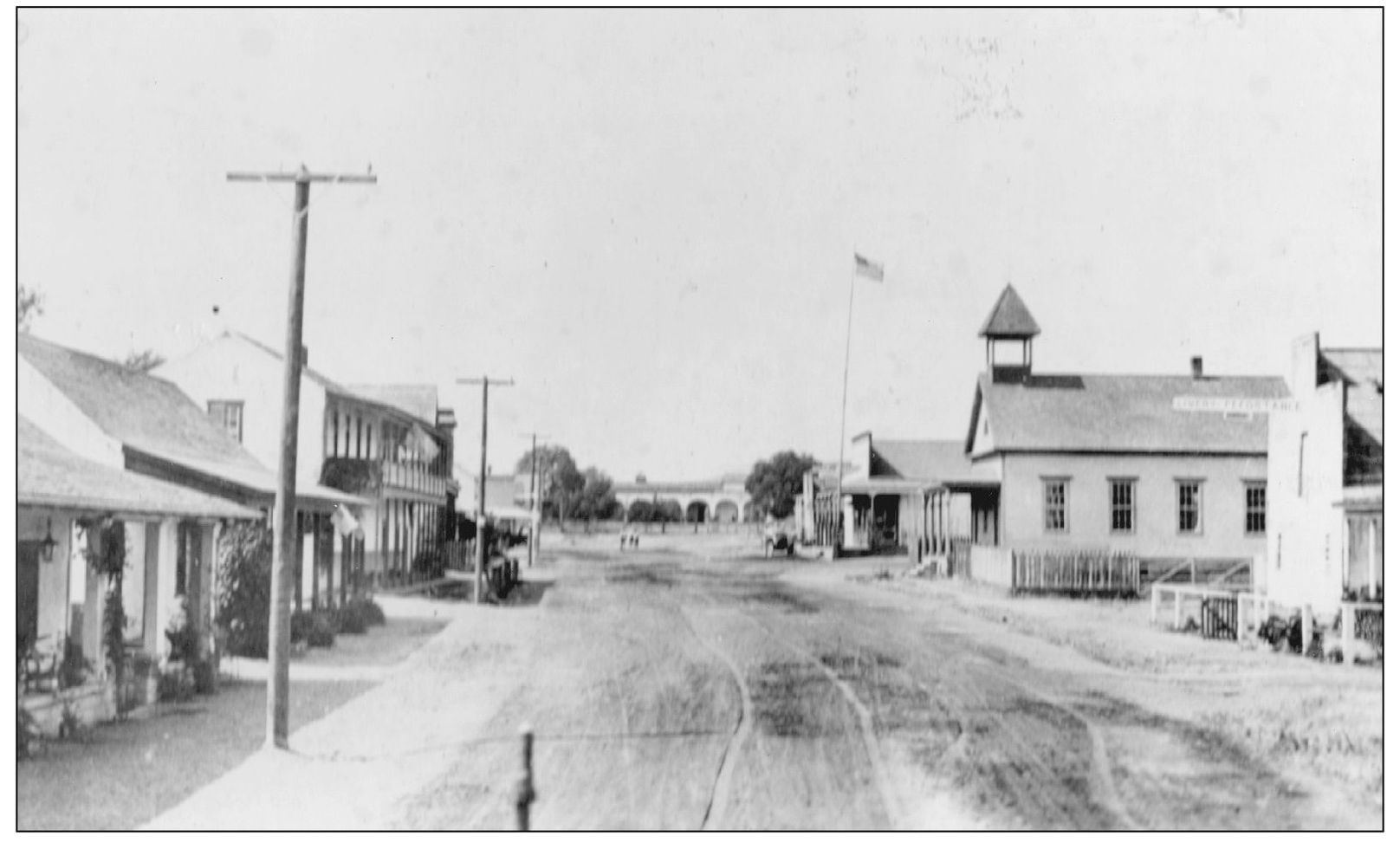

This is another view of Camino Capistrano, looking toward the mission sometime between 1912 and 1915. The schoolhouse has just been moved and is not yet transformed into the Palm Restaurant (right). There does not appear to be any pavement in the rutted road. The mission at the end of the street still has a picket fence—an amenity that was removed prior to the construction of an adobe wall.

The Echenique House, now Four Oaks Park, was the home of Mr. and Mrs. Cornelio Echenique, who are pictured here with Bonifacia Lacouague. In 1914, the Echeniques were out of the sheep business and had 10,500 acres dedicated to cattle. Nearly 7,000 acres were sublet to grain and lima bean farmers. The park is in San Juan Terrace, built in the mid 1960s.

This is a popular view of Camino Capistrano, looking north toward the mission. The Palm Café (at right) has been enlarged and is sporting a new façade, and the mission’s new adobe wall appears to be nearing completion, placing this photograph in early 1919. Woodmen’s Hall, north of the Garcia Adobe (far left), is still downtown.

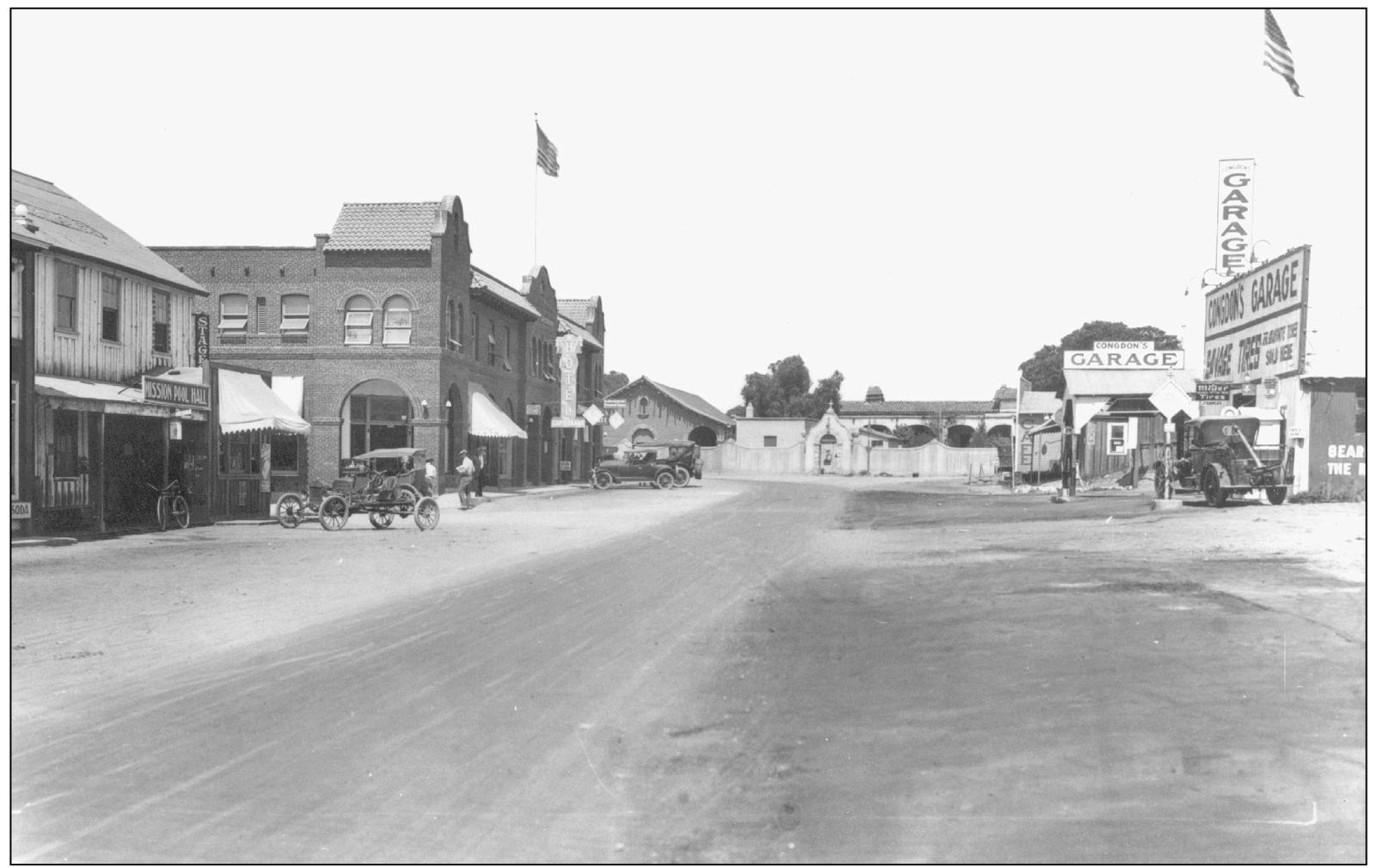

The Capistrano Hotel, the first to be advertised as “absolutely fireproof,” appears at the left of the photograph. Built by Fred Stoffel in 1920, the building was made of brick instead of wood. Stoffel and his wife, Louise, purchased the San Juan Inn in 1916, north of the new edifice, only to have it burn down within two years. They rebuilt it in 1918.

This view is of Camino Capistrano, looking southwest in front of the Capistrano Hotel, which was completed in 1920. The towers of the new Romer and Kelly building (center) are evident for the first time. It was constructed at the old location of the Woodmen’s Hall in 1919, the year the hall was moved to Verdugo Street next to the packinghouse.

On May 9, 1916, the mission began charging a 10¢ admission fee to raise money for preservation efforts. The grounds were only loosely enclosed with a picket fence, but in 1917 the fence was removed and construction began on an adobe wall. The brickwork was completed September 1, 1917.

This bird’s-eye view of Mission San Juan Capistrano shows progress made by the late 1920s. The wall around the front of the mission is complete, the rest of the grounds appear to be fenced, the front courtyard is landscaped, and the buildings are reroofed. The northern section of the quadrangle was rebuilt in 1926 and 1927 to house the new Mission School that opened in 1928. The second floor of the rear section served as the residence for Fr. St. John O’Sullivan, the resident priest. Though no landscaping yet appears in the inner plaza, work has been done to stabilize the Serra Chapel in the eastern section of the quadrangle. The town, as well, shows signs of growth.

The mission in the late 1920s was a showplace. Dubbed the “Jewel of the Missions,” it earned its nickname through the careful restoration of the Landmarks Club and Fr. St. John O’Sullivan. The motorcar was now a prominent mode of transportation, and the mission was a “must see” in most guidebooks.

The fledgling film industry discovered the mission and the town as a wonderful location for such films as 1927’s Rose of the Golden West, starring Mary Astor and Gilbert Roland. The first movie shot in San Juan was D. W. Griffith’s The Two Brothers in 1910.

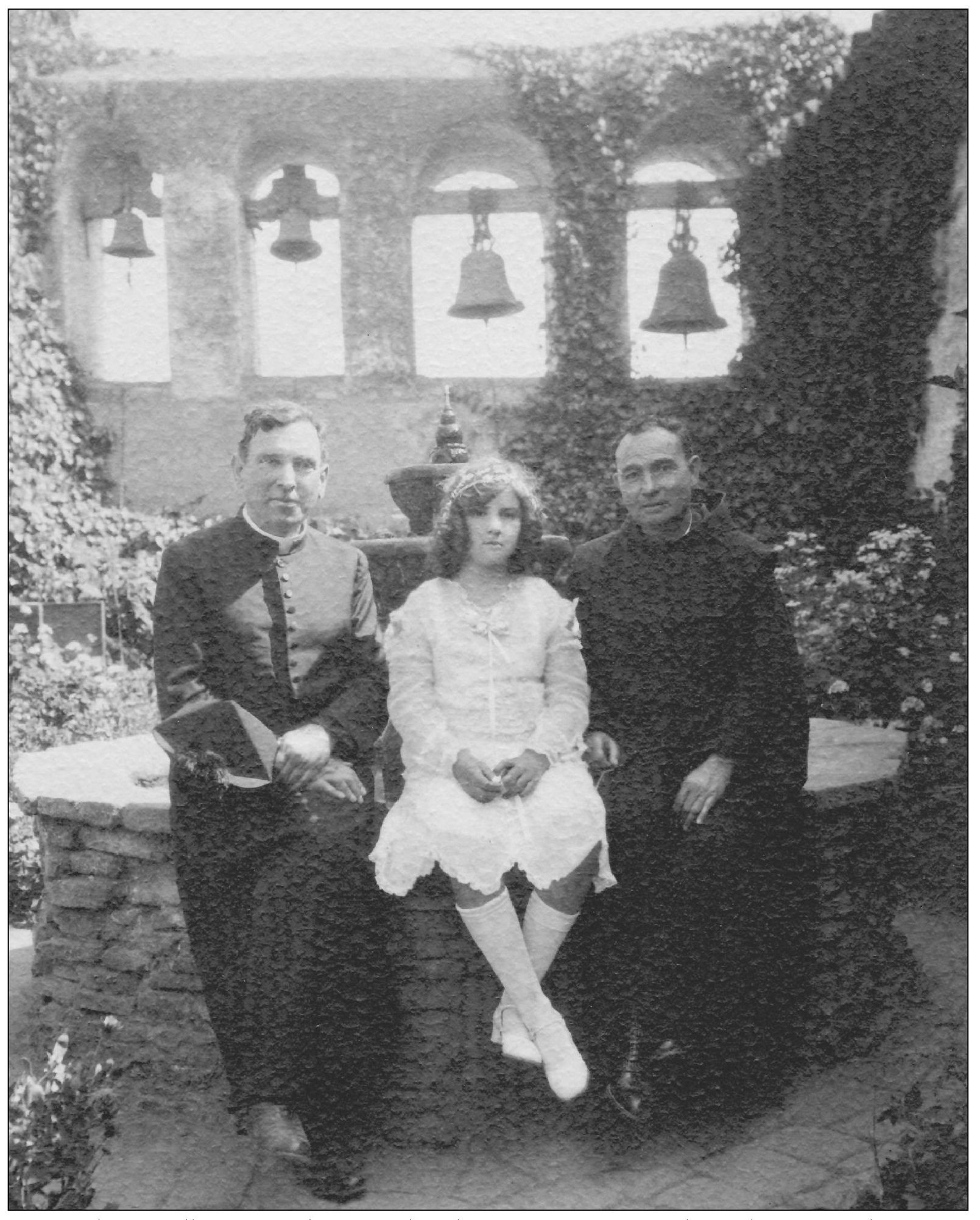

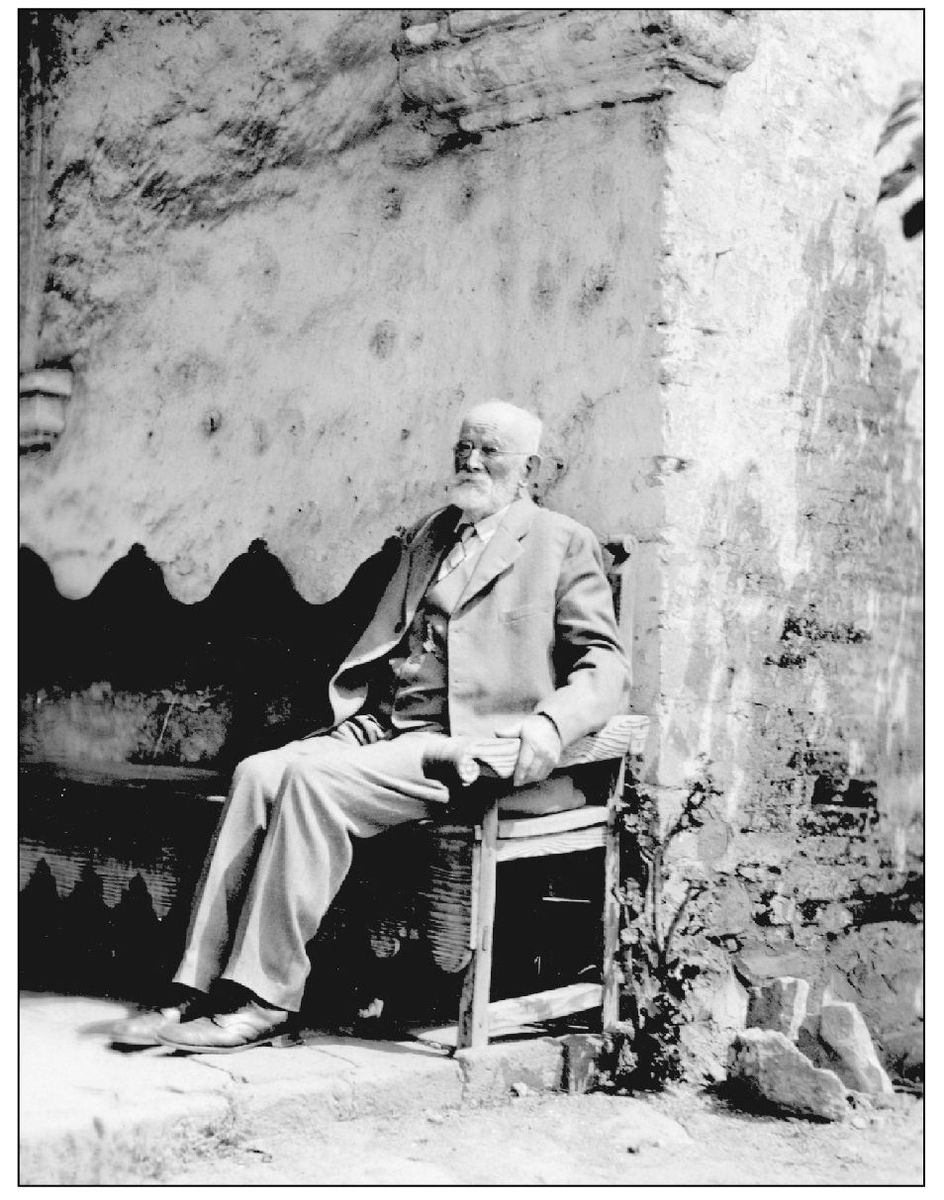

Fr. St. John O’Sullivan, at right, arrived at the mission in 1910 and was the first resident priest since 1886. The place was characterized as “ruined, despoiled, and apparently useless,” but it was where O’Sullivan wanted to be. Plagued by illness his entire life, the 36-year-old priest wanted to restore the mission and create a community of parishioners. From 1912 to 1929, the works of restoration proceeded and not only were the buildings restored, a new rectory, convent, and school was built. The group, including Jane Magee and an unidentified man, sits in the “sacred garden” behind the campanile of bells, between the west wall of the Great Stone Church and the east wall of the sala. This garden and fountain were O’Sullivan’s personal creation and inspiration—a place of peace and solace. He died July 22, 1933, and is buried on the mission grounds nearby.

The interior of the Serra Chapel includes a reredo and an altar of carved, gilded cherry wood made in Barcelona Spain. It was brought to San Juan in 396 pieces in 1924 to be reassembled in the chapel, where it is today.

This stylized photograph of the mission appears to be one taken for the novel For the Soul of Rafael, which was first published in 1906. Marah Ellis Ryan’s book was extremely popular and was reprinted several times. Capt. Stanislado Morales and Lucrecia Yorba appear in some of the illustrations, although this one was not used in later publications.

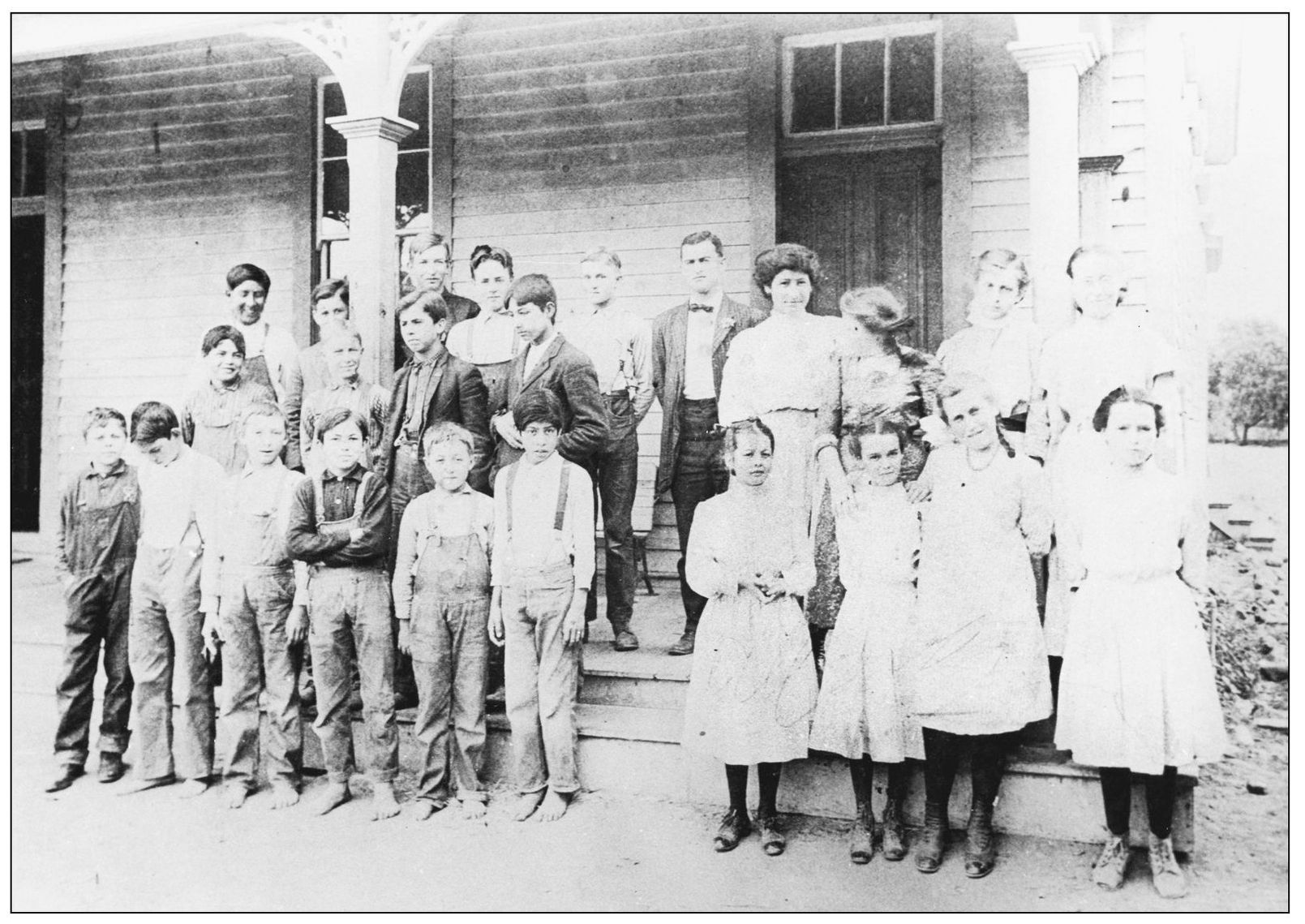

A group of children pose outside San Juan School in 1907. Ruth Enuerl, pictured among the boys in the top row, was the primary teacher. William McPherson (top row, center) was the principal. By 1910, enrollment in the school was 23 and by 1964 it had grown to 475. The building was replaced in 1912.

A handsome new elementary school replaced the old wooden building around 1912. The old building was moved downtown and became a restaurant. Built in the Mission Revival style, the school boasted two bell towers and housed eight grades. It was in use until 1964 when it was torn down and replaced by a new San Juan Elementary School.

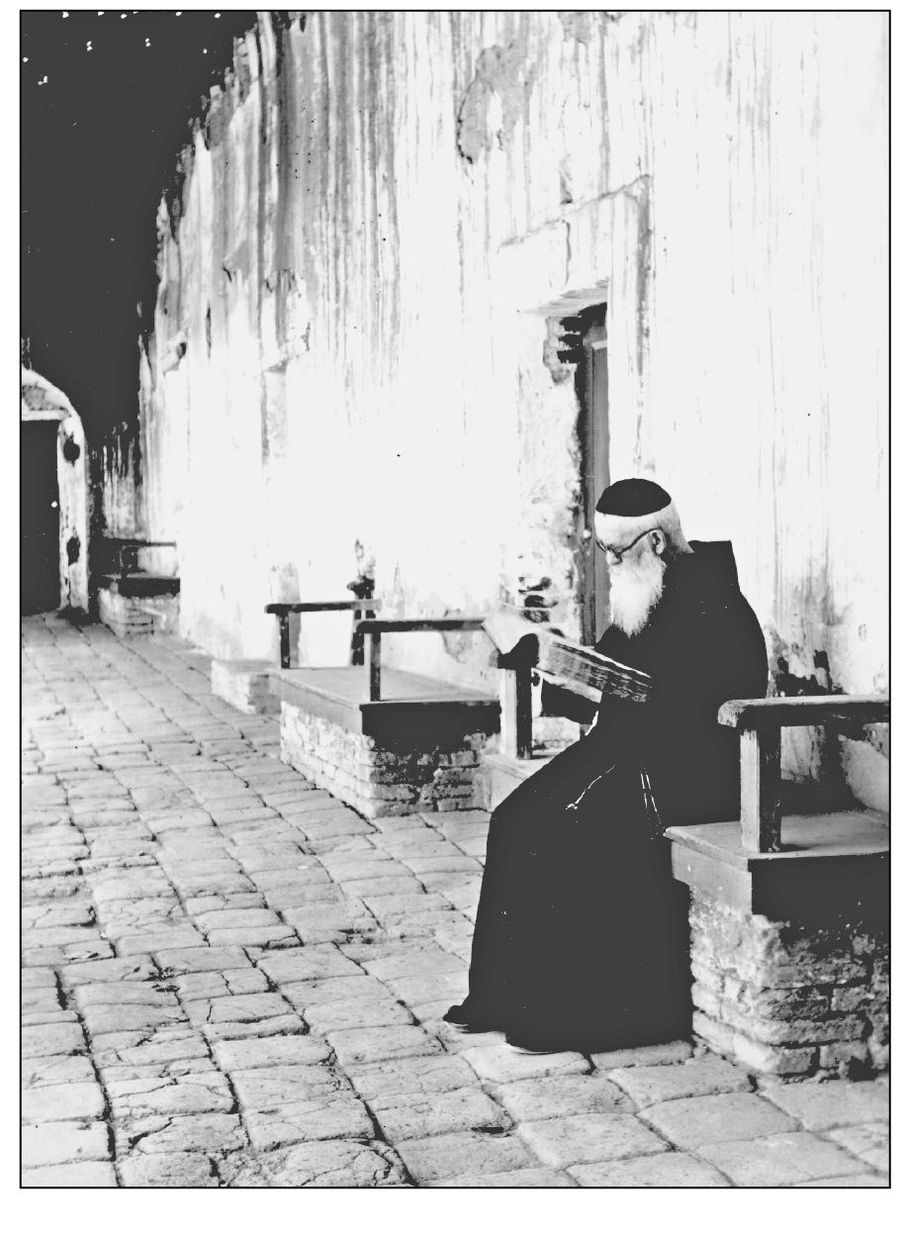

Jose de Gracia Cruz, or “Acu,” rests in a corridor of the mission. Acu is credited with telling Father O’Sullivan the story of the swallow’s return to the mission in a book called Capistrano Nights, published in 1930. He died in 1924 after serving many years as the official mission bell-ringer, and his tale lived on.

Another colorful figure lurking about the mission in the 1920s was Fr. Zephyrin Engelhardt, who was the biographer of Fr. Junipero Serra and author of a series of books about the California missions. Engelhardt quoted several documents that he was privileged to see before they were destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake and fire.

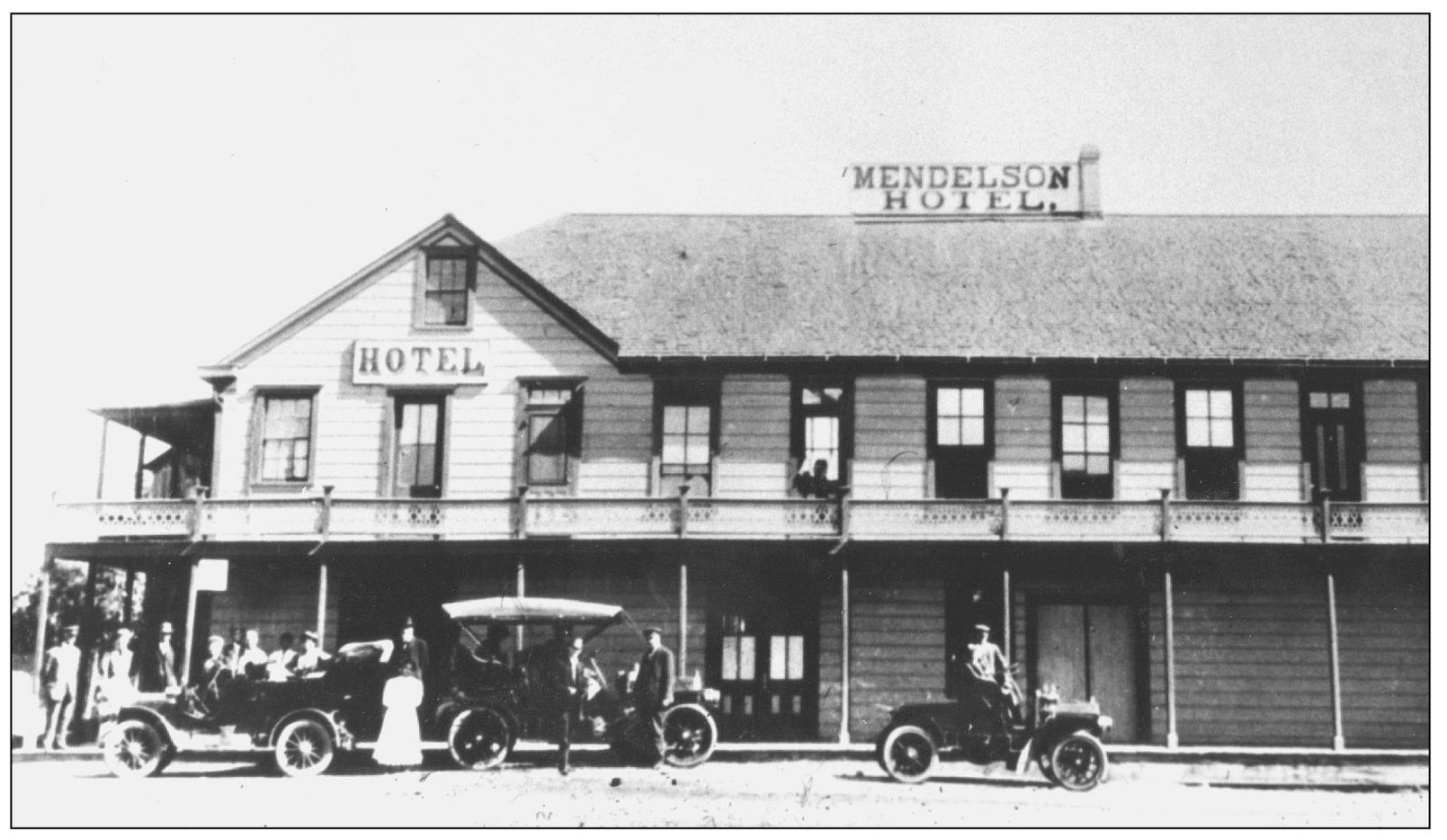

The Mendelson Hotel, dating back to stagecoach days in 1875, was one of the most popular places in town to stay. Located on El Camino Real near Yorba Street, the property was upgraded over the years and catered to many movie companies as well as travelers. An early advertisement boasted that hot meals were available “on three hours notice.” A park occupies the space today.

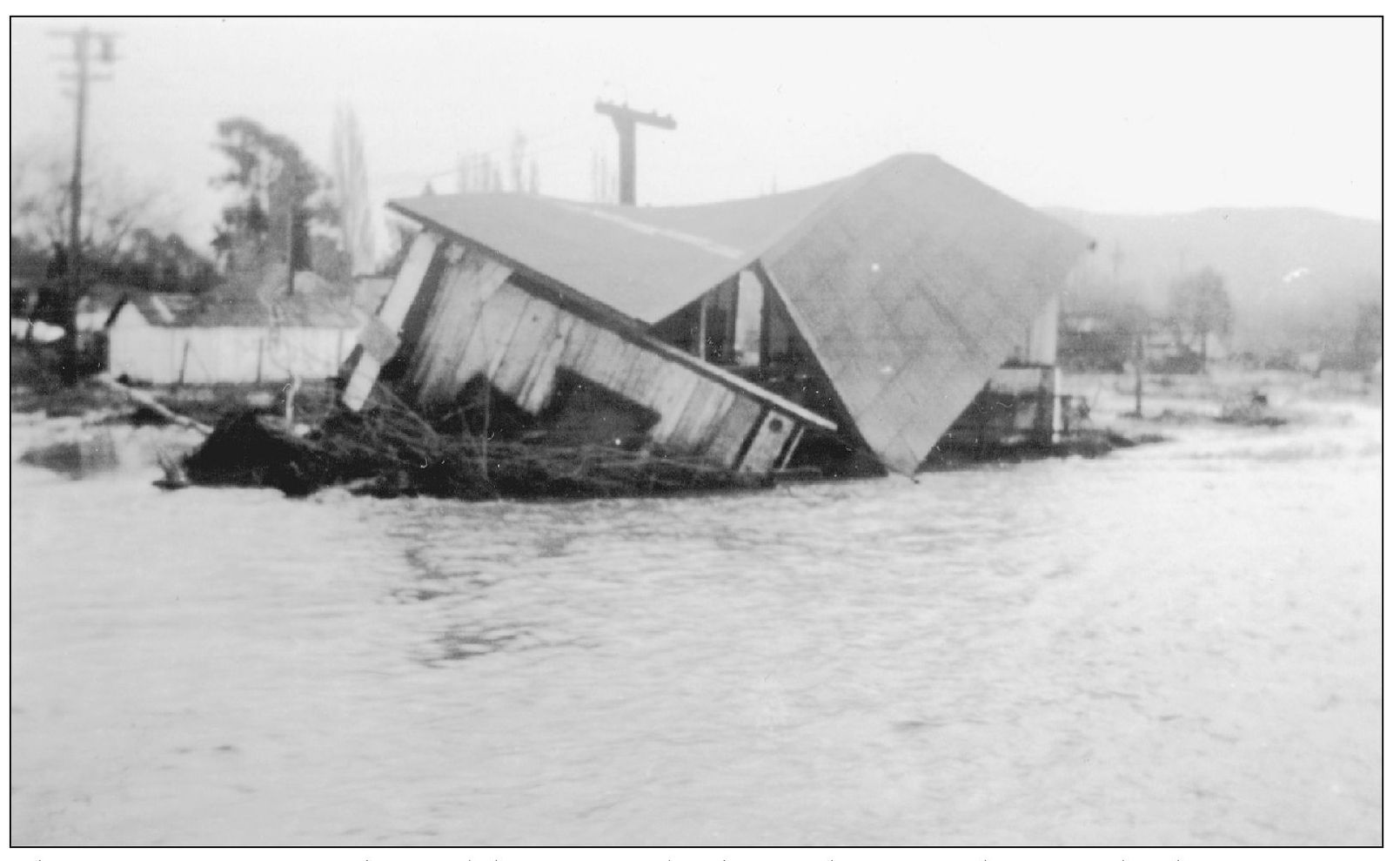

The community survived several devastating floods over the years. The worst floods were in 1916, 1938, and 1969. Both the Oso and Trabuco Creeks converge just north of town, and the San Juan and Trabuco Creeks join about a mile south of the mission. In this photograph, a house is being swept downstream in one of the earlier floods.

This is a view from the hill east of the valley looking northwest, probably the former Honeyman Ranch. The rear of the old San Juan Elementary School, which stood between 1912 and 1964, is pictured at center; the mission is at left center. Orange groves dominated the landscape as the major crop in the valley from the 1930s through the 1950s. John Daneri is listed as having oranges in the 1890s, but orange groves weren’t planted extensively until 1914 and did not replace the English walnut industry as the major valley crop until the 1930s. The hills in the background are completely undeveloped. Although difficult to see, Spring Street, a portion of which still exists, is at the left of the school buildings.

The Canedo Adobe, sporting a flag during World War I that indicated how many family members were involved in the war, had a number of uses and owners after Salvador Canedo’s demise from smallpox in the 1860s. At the turn of the century it was used as a place where bodies were prepared for burial and wakes were held. Later it was a home and office.

Mission ruins, probably the north wing before restoration, are viewed by one of many visitors who came each year to study its architecture, paint its romantic ruins, or write fanciful stories set in the rancho days. Father O’Sullivan enjoyed the company of artists, and he also encouraged the work of writers such as Charles Saunders and playwright Garnet Holme.