Seven

POSTWAR CHALLENGES

1950–1974

In 1957, work began on Interstate 5 despite forebodings of gloom for tiny San Juan Capistrano. People were concerned that this bypass would ruin the town’s economy and propel the mission into obscurity. Instead, it made it easier for tourists to get to town, contributed to a building boom, and inflated land prices to such a degree that agriculture was no longer the highest and best use.

The first housing development, the Stoffel tract, was completed in 1951 at the south end of town, followed by San Juan Park off the Ortega a few years later. In the 1960s, orange groves were torn out for more houses; Del Obispo Street was built from Camino Capistrano to Ortega Highway, opening land for expansion of the downtown.

Rapid growth in population and fears of a takeover by an adjoining city caused community leaders to move toward incorporation. Voters approved the move and San Juan Capistrano officially became a city on April 19, 1961. Population growth soared from 1,000 people in 1960 to 12,850 in 1970. Several mobile home parks were built along with housing developments on both sides of the freeway. Low water supplies, which had held back growth for decades, were supplemented by joining the Metropolitan Water District in the 1960s. In the early 1970s, residents voted for candidates that would preserve the town’s character and slow growth. Too many landmarks had been lost. Hillsides, horses, and history became important issues in the decades to follow.

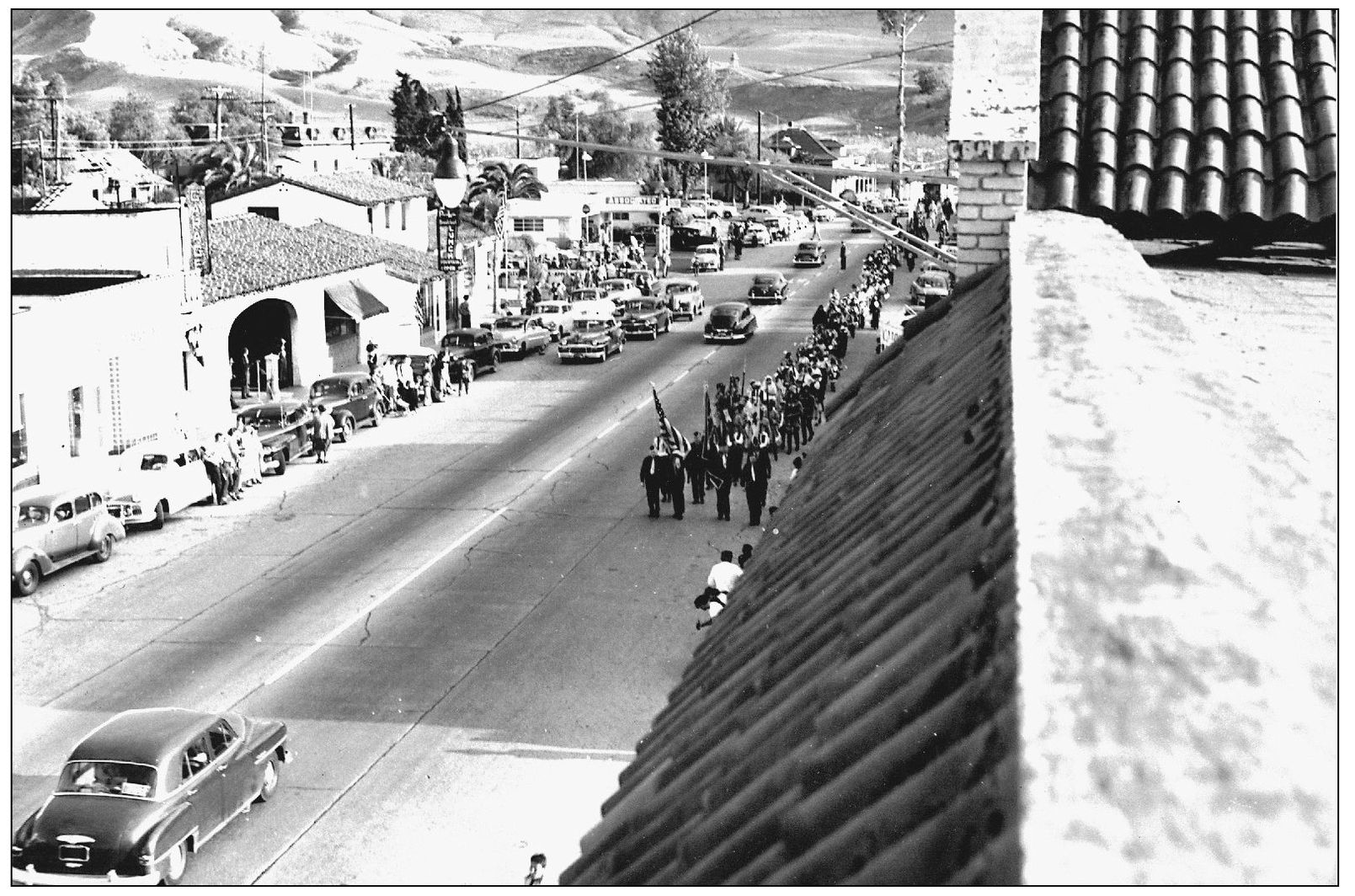

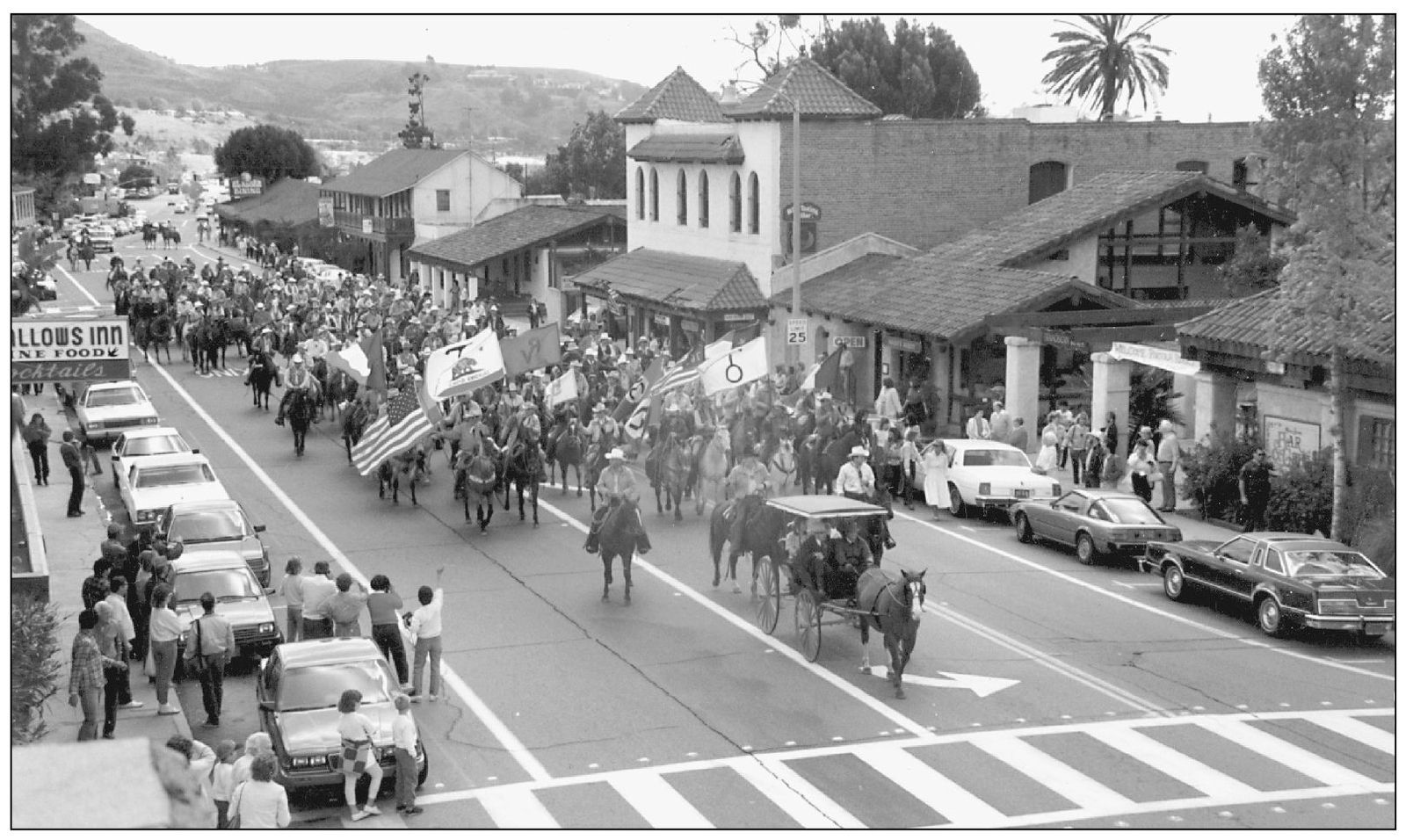

Since 1958, parades have been an integral part of the Fiesta de las Golondrinas, the event that celebrates the return of the swallows to San Juan Capistrano on March 19. The non-motorized parade that features equestrian and walking units is generally held on a Saturday.

Earlier parades, dating back to the 1930s, were held on Swallows’ Day, but were not as organized or formal as they are today. This shows a group from 1951, marching up Camino Capistrano toward the mission. The road is shared, not closed, and there are fewer spectators. The town population was less than 1,000 in the 1950s and was about 1,200 when the city incorporated 10 years later.

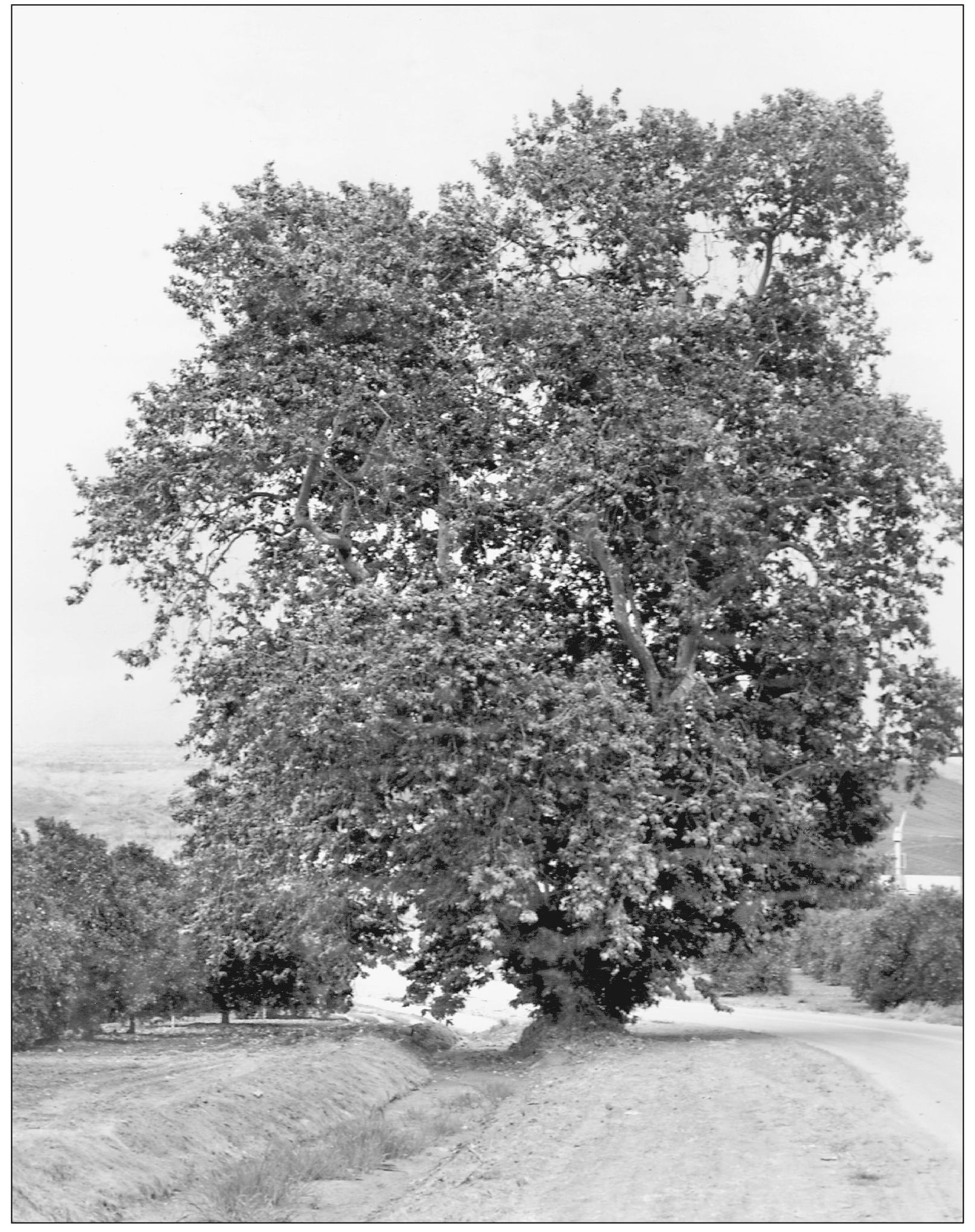

The sycamore on Junipero Serra Road, just west of the freeway, has its own unique story. Long believed a gathering point for bandit gangs in the rancho period, it was unfortunately in the way of the feeder road for the new freeway when it was first designed about 1957. A group of local citizens, outraged that the tree would be removed, embellished the story and sent a delegation to the state to plead for the tree. They said it was Joaquin Murietta’s gang that used the tree and it could not be lost. At great expense, the freeway off ramp and feeder road were redesigned and the tree was saved. There is no evidence that Joaquin Murrieta used the tree for any purpose, since his activity took place in other parts of the state. The tree still stands.

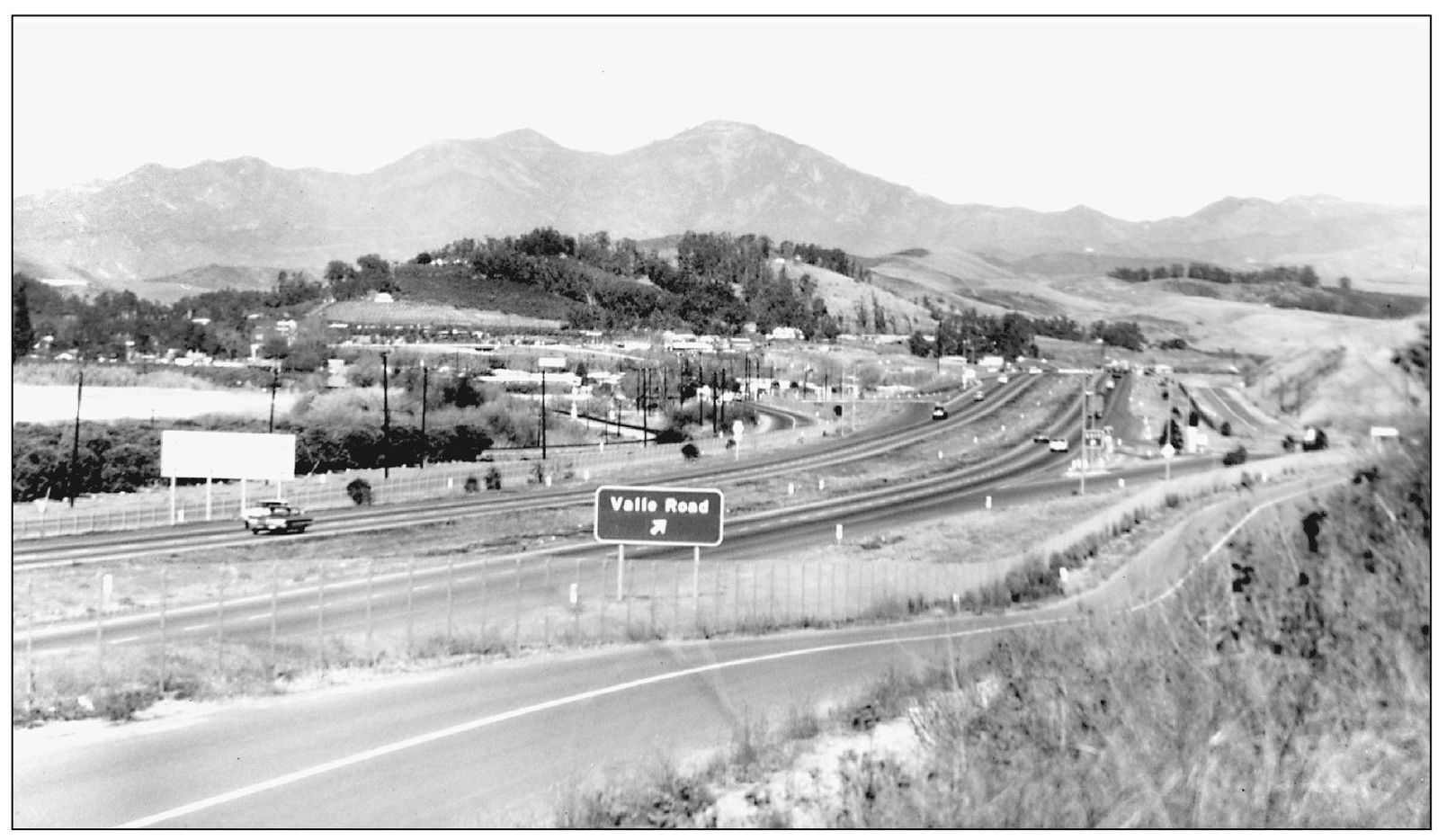

This bevy of beauties is on hand for the ribbon-cutting to open the freeway through San Juan Capistrano in 1959. Called the Santa Ana Freeway, it is a link of Interstate 5, now called the San Diego Freeway. Originally opposed to the freeway, locals thought downtown would die. Instead, it made it easier to get to the community and opened land for development.

Interstate 5 opened in 1959 and is still the major north/south corridor through the city, replacing Highway 101 (Camino Capistrano), which was opened in 1915. The east/west connector is Highway 74, called Ortega Highway, and the interchange between the 5 and 74 is due for a major upgrade in the next 10 years because of development pressure from the east. This view looks north.

Looking directly east through the arches of the Capistrano Depot is the old Ferris Kelly building, which in 1961 became Capistrano City Hall. The city incorporated on April 19, 1961, and leased space in the then-vacant building that had been Connor’s Department Store. This view was not possible until the Capistrano Hotel was demolished and now another building blocks it.

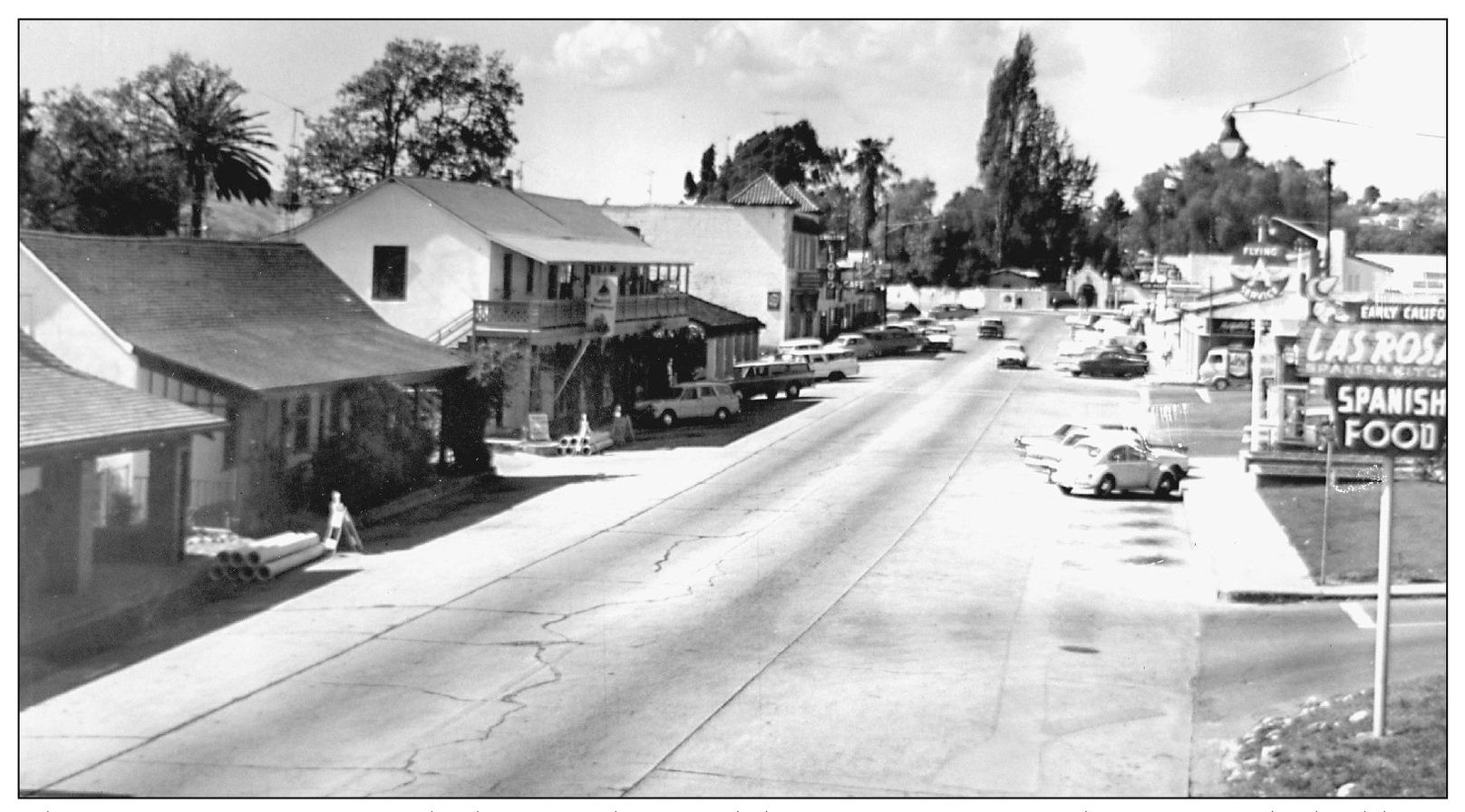

This is Camino Capistrano looking north toward the mission entrance about 1960. The buildings on the left look the same; the buildings on the right are still changing. Marcos Forster’s Casa Grande still stands, as evidenced by the Las Rosas sign. It was leased by his heirs as a hotel briefly, but spent most of its life thereafter as a restaurant. A Flying A service station is where a small park is today.

The Twin-Winton building was a prominent ceramics business downtown for many years., just south of the Judge Richard Egan house. It was preceded by a firm called Brad Keeler Artware. Twin-Winton was known as the home of the famous “Kit-Kat” clocks. The building was torn down in the 1980s to make room for a shopping center.

A mural on the walls of Twin-Winton, designed by Jean Goodwin Ames, was saved when the building was torn down. It was made of tile and depicts all the elements used in making pottery: fire, earth, the potter, and water. When Mercado Village was built, it was incorporated into one of the courtyard walls and can still be seen by visitors to the shops.

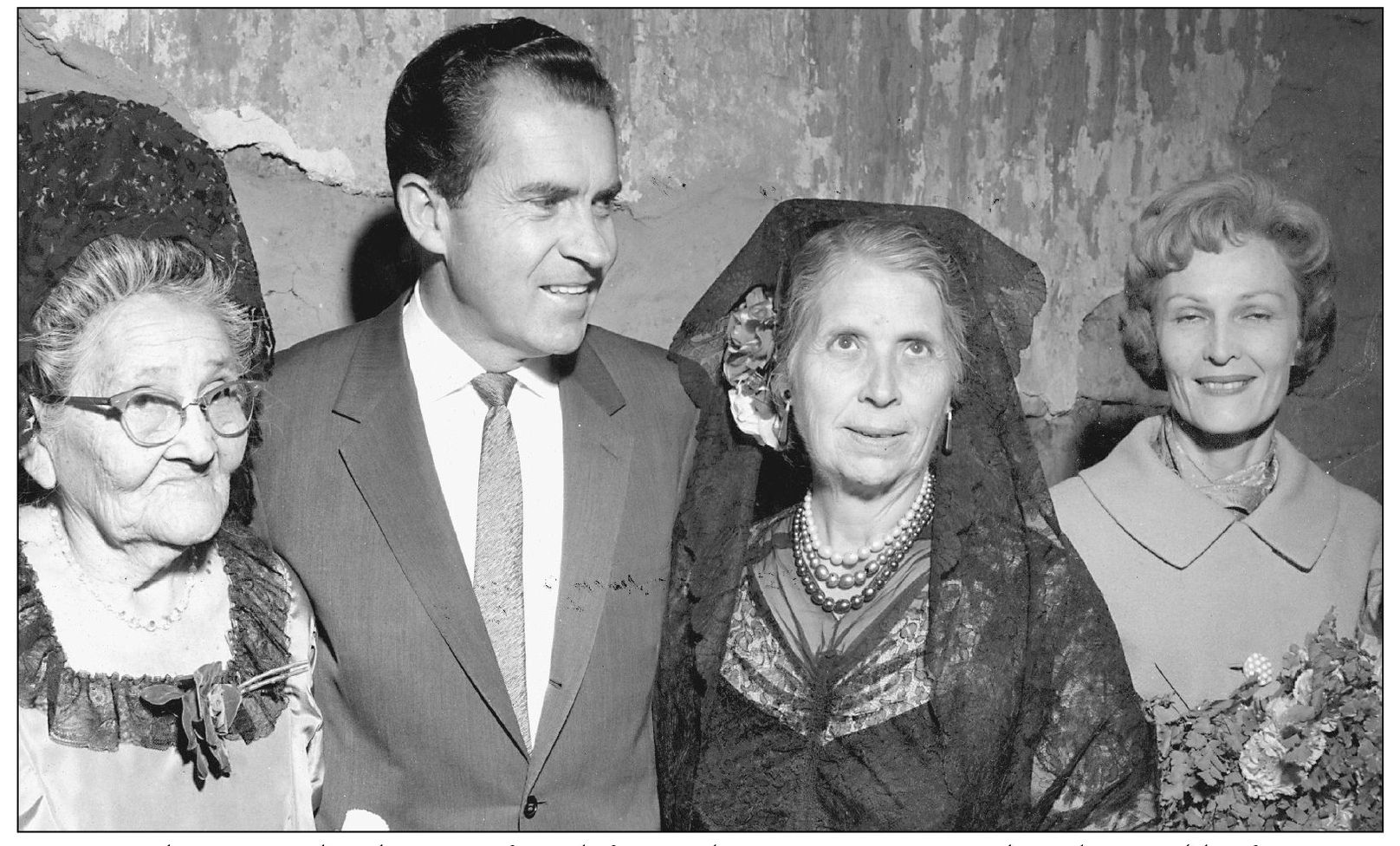

Posing with Pres. Richard Nixon, from left to right, are Vivian Ricardes Olivares (the first town matriarch), Lucana Forster Isch, and his wife Pat during one of the president’s many visits to San Juan Capistrano. The Nixons owned an estate in nearby San Clemente, known as the “western White House,” and were fond of Mexican food served at the El Adobe Restaurant in downtown Capistrano.

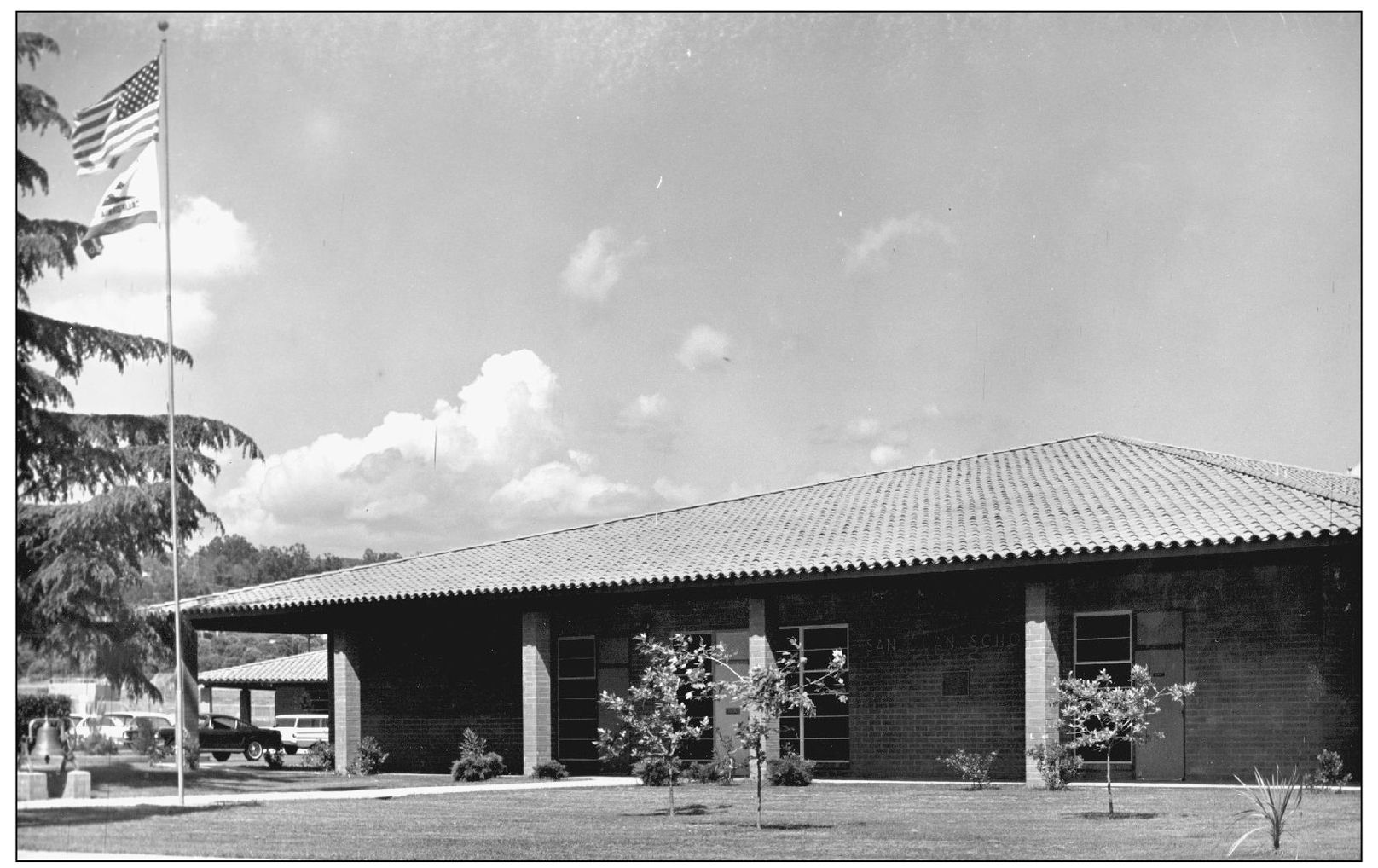

San Juan Elementary School was built in 1964 on El Camino Real across from the east gate of the mission. It replaced the Mission Revival–style building from 1911 to 1912, which had, in turn, replaced the wooden schoolhouse from the 1870s. The original building was believed to have been an adobe when the school district was formed in the early 1850s. Records date back to 1853.

El Viaje de Portola, a group of equestrians, have been a mainstay of the Fiesta de las Golondrinas parades for decades. Originally formed in 1963, the group gets together once a year to commemorate the Portola expedition of 1769 by having a trail ride along those portions of the same route that are still undeveloped. This 1987 group is on its way to the mission for the annual blessing.

In 1939, Leon Rene wrote the song “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano,” which was recorded by many famous people, including Bing Crosby and, years later, Pat Boone. Radio and television broadcasts from the mission on the day of their return have drawn large crowds of people to the mission every March 19 to see the swallows. Festivities have taken place inside the walls for decades. This photograph is from 1960.

A birds-eye view shows San Juan Capistrano as it looked in the mid-1960s when San Juan entered a period of rapid development; the mission is at the top of the photograph and Camino Capistrano is at the center. It was also a time when several significant buildings were lost: the Canedo Adobe, the Capistrano Hotel, and the Casa Grande—all in the name of progress. Housing developments sprang up north and east of the mission, and orange groves were pulled out of the valley floor. In 1974, the city took action to revise its General Plan and slow the growth. A number of preservation efforts were organized to keep the landmarks that remained in the community and to define the area’s character.

Carl and Adele Hankey stand outside their farmhouse on the Ortega Highway that they purchased in 1921. Built in 1884 by Joseph and Amy Rowse, the Victorian farmhouse was once owned by Fr. Alfred Quetu. Hankey, who owned 21 acres of oranges, served on the Orange County Road Commission in the 1930s. The house still stands, but is surrounded by housing developments.

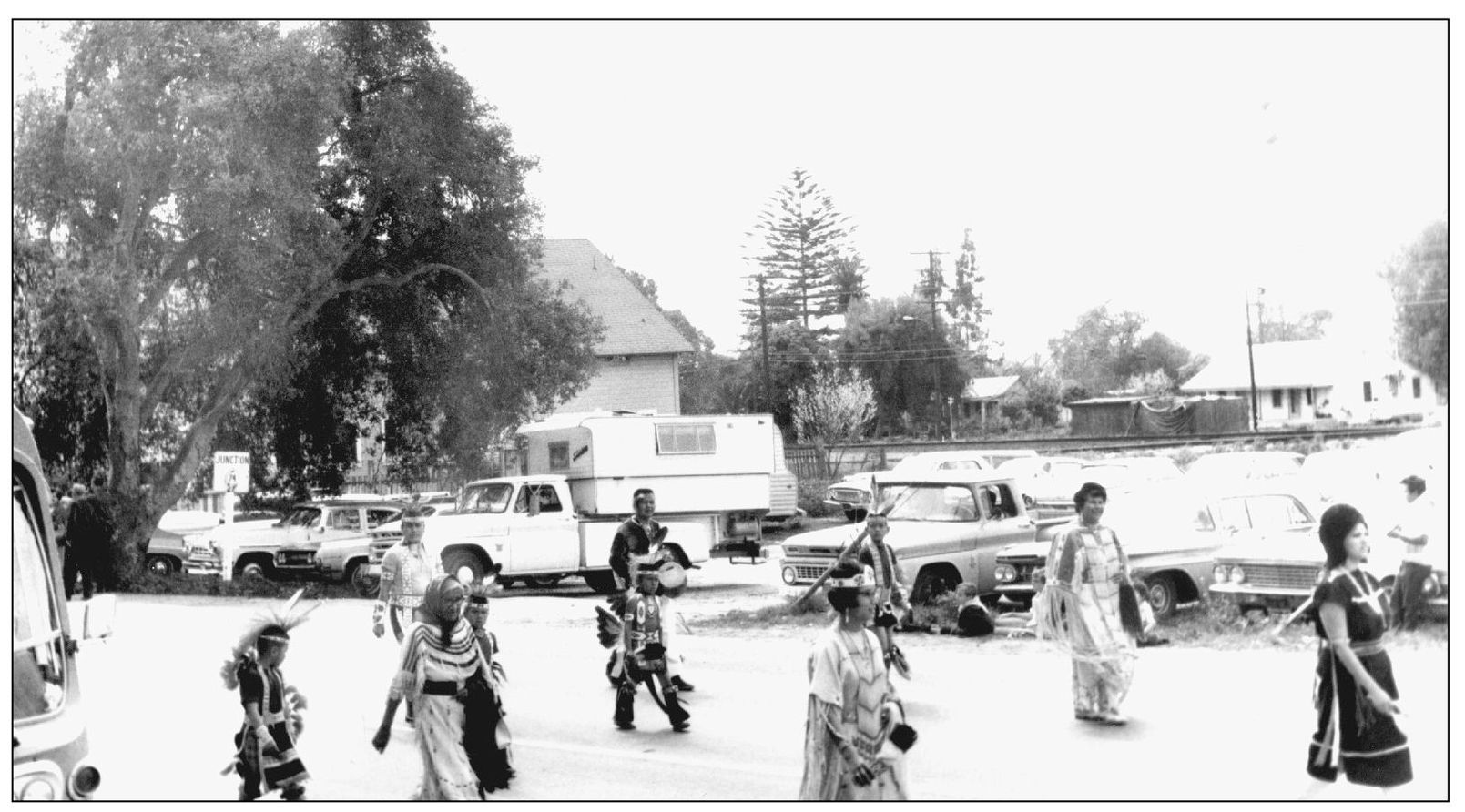

Native Americans from the local community have always marched in the Fiesta de las Golondrinas parades. This group, around the early 1960s, marches north on Camino Capistrano past the site of the Mission Hacienda Plaza today. The Juaneno Band of mission Indians has applied for tribal recognition, which is pending. Many people in the community are proud to trace their heritage to this group.

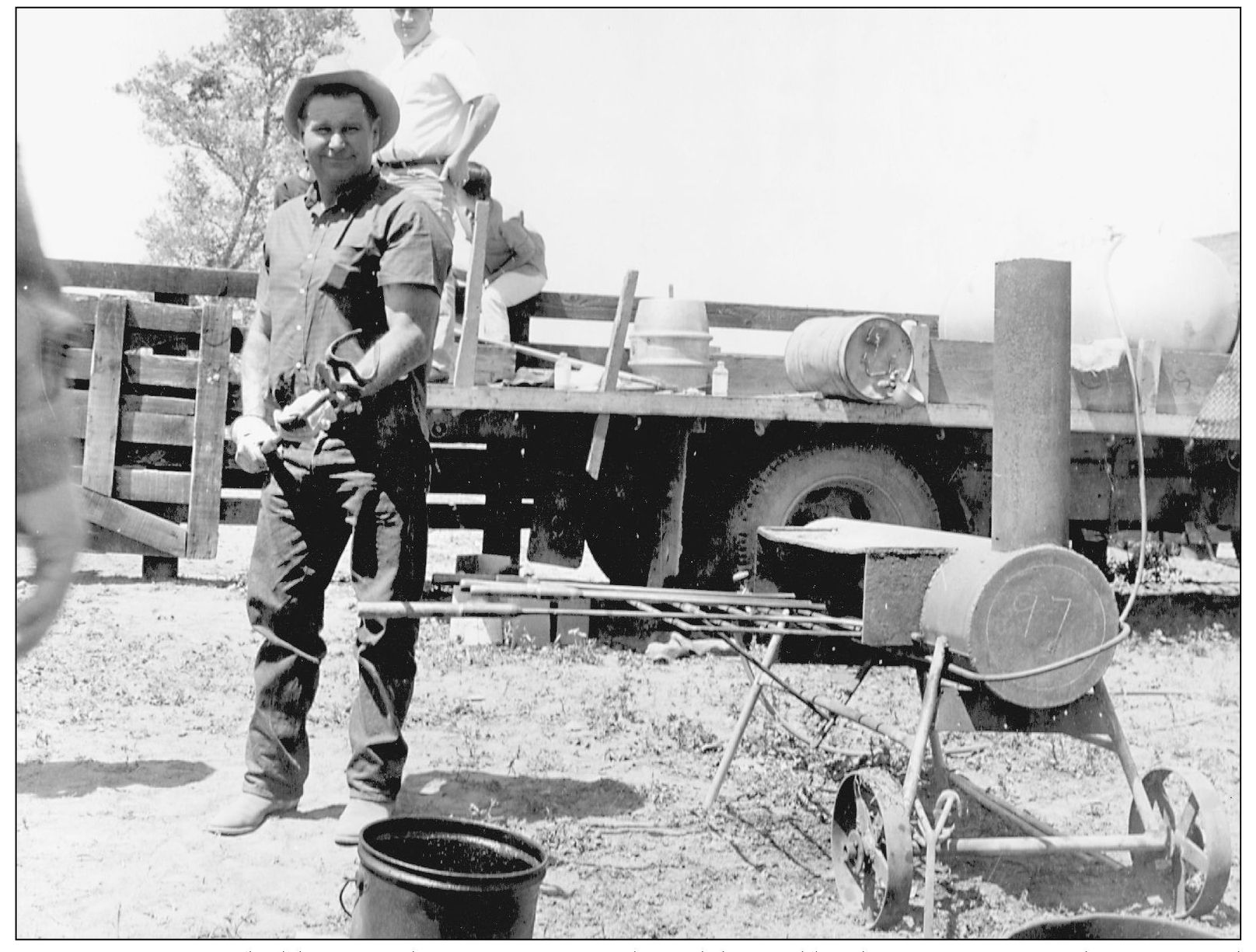

Joaquin Errecarte holds a Rancho Mission Viejo brand, heated by this unique stove that was used in the field for roundups. Branding was necessary during the rancho period because there were no fences. Cattle from different owners sometimes strayed together, and without brands could not be returned to their owner. Brands are still used to mark cattle, but more as a tradition.

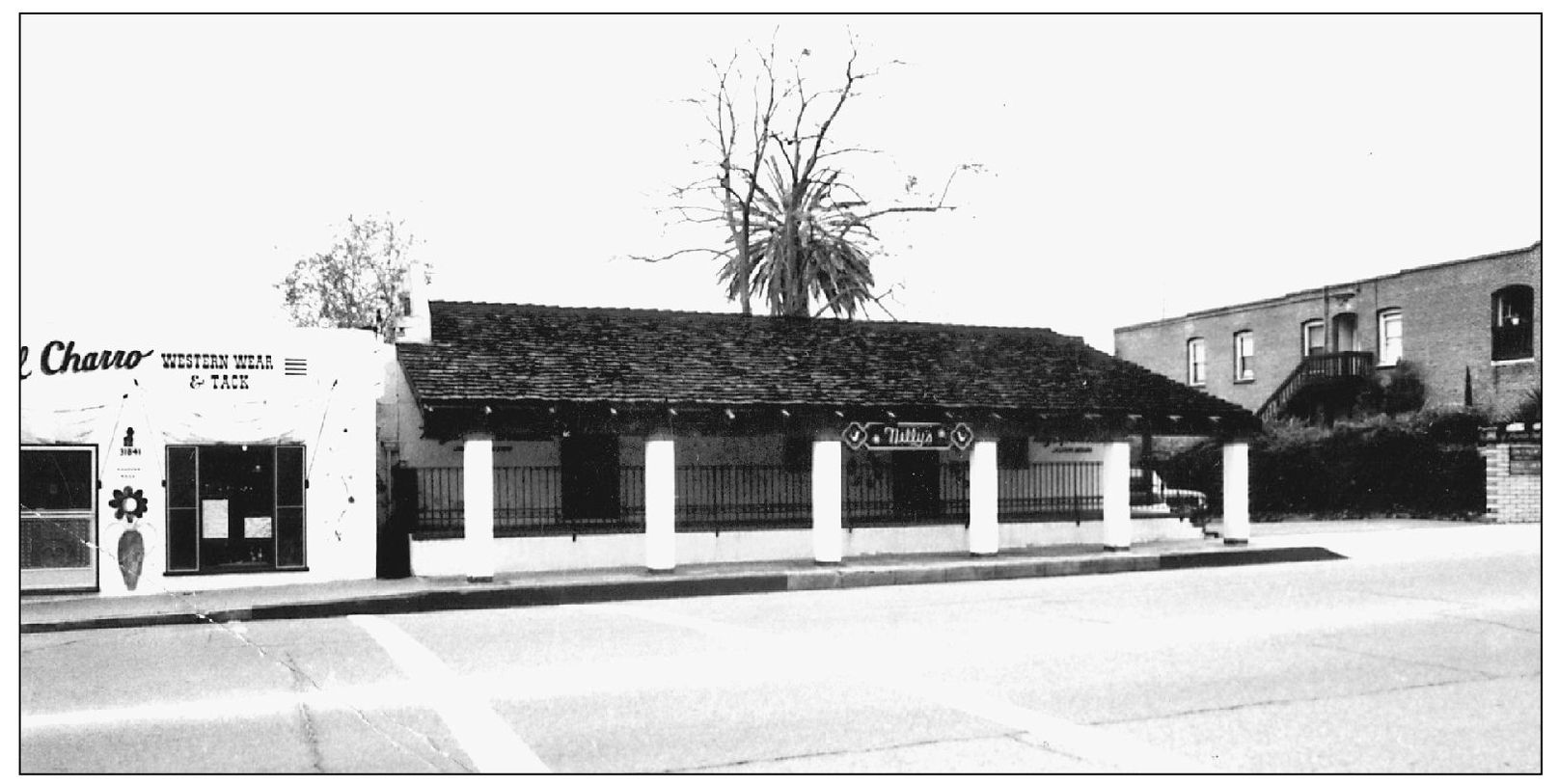

The Juan Avila Adobe, rebuilt in this two-room section after the fire of 1879, survives today on Camino Capistrano. In this 1975 photograph it was a dress shop called Nelly’s of Puerta Vallarta. Believed to have been built in the 1840s, it was once a justice court and a public library. The residence once had 10 rooms, stretching north along Camino Capistrano.

The Garcia/Pryor House, now the O’Neill Museum, was built in the 1870s by Dolores Garcia for his wife, Refugia Yorba, on property behind today’s El Adobe Restaurant. Garcia was murdered in 1896 and the property sold in 1903 to Albert Pryor, whose family lived there until 1955. In 1976, the Cornwells, owners of the El Adobe property, donated the building to the San Juan Capistrano Historical Society. It was moved to its permanent home at the corner of Los Rios and River Streets, where it was restored and serves today as a house museum and office for the society.