I

At the Center of It All

Then God spoke all these words:

I am the LORD your God who brought you out of Egypt, out of the house of slavery. You must have no other gods before me.

—Exodus 20:1–3

When I told my wife that I felt compelled to write a book on the Ten Commandments, she gave me a quizzical look and said, “Really, why?”

I was puzzled by the question, so she continued. “I know the Ten Commandments are important. I believe them and try to live them. But I wonder how relevant they are to most people. Most of us don’t plan to murder or steal. And who is tempted to worship other gods these days?”

Now it was my turn to raise an eyebrow.

“Okay,” she said, “I know—we all struggle with our own false gods. But you know what I mean.”

Her response was understandable. At first glance, the commandments do seem written for a different age (“Thou shalt have no other gods before me. Do not make for yourselves idols”) or so basic that we hardly need reminding (“Thou shalt not murder”). But if you dig in a little, understand their historical context, and listen to how Jesus and the apostles interpreted them, you’ll find these ancient words speak in profound ways to our lives today. Jesus, in particular, looked behind the rules to the condition of the heart each commandment sought to address. Murder wasn’t just the act of killing, he taught. It was resentment and bitterness and hate and the words that spring from them. It wasn’t just the act of adultery but desire and the myriad ways sexuality can be misused. We’re no longer tempted to worship the gods of the Egyptians and Canaanites, but we still struggle with misplaced devotion and making our pride or career or wealth the god we worship and serve.

But Jesus did more than look at the deeper issues. He had a way of turning the commandments on their head. As I noted in the introduction, for each thou-shalt-not there is an implied and important life-giving thou-shalt. In other words, rightly understood, the commandments don’t merely tell us what not to do. They point us, positively, toward how we’re meant to live our lives—toward God’s will for us in the midst of our deepest struggles. Nowhere is this truer than with the first command, I am the LORD your God.

Essential Religion and Ethics for a New Nation

Before we explore the first and most important of the commandments, I’d like to remind you of the context of the Ten Commandments in the biblical story.

It was a famine that led Israel and his children and grandchildren to travel to Egypt in search of food. Beginning around 1800 B.C., they and tens of thousands of other Semitic people migrated to Egypt’s lush Nile delta, a region of some five million acres of fertile land. These populations eventually formed a nation within a nation, of which Israel’s descendants were one small part.

Later, another wave of immigrants entered the area, a people the Egyptians called the Hyksos (the word meant, in essence, “foreign rulers,” though it was used at times with the sense of “shepherd kings”). Also of Semitic origin, they went on to wrest control of the Nile delta, and then much of the rest of Egypt, from Egypt’s ruling dynasty. These foreign invaders ruled over much of Egypt until about 1550 B.C., when they were expelled by several succeeding pharaohs marching with their armies from Thebes. Many of the foreigners who remained in Egypt, including the Israelites, were made slaves of the Egyptians.1

The Israelites spent generations enslaved and oppressed in Egypt. Among other things, their labor was used to form the mud and straw bricks that went into the massive building projects of the New Kingdom pharaohs. The Israelites did not build the pyramids—these predate the Israelites by many hundreds of years. But from approximately 1550 B.C. to perhaps as late as 1279 B.C., the Israelites were forced to make tens of millions of bricks, which were used to build Egypt’s temples, cities, and walls. You’ll find them at most ancient archaeological sites from the period, including the magnificent Luxor Temple.

Exodus records that even under oppression, the Israelite population multiplied. It got to the point where the Egyptian pharaoh feared that these foreigners, like the Hyksos before them, might one day pose a threat. So he escalated their oppression. Slaves were made to work harder, keeping the Israelite people under the foot of the powerful Egyptians. Boys born to Israelite women were ordered to be drowned. All of which leads to the story of Moses, found in the opening chapters of the book of Exodus.

When Moses is born, his mother, Jochebed, devises a plan to save him from Pharaoh’s decree. It appears she knows of one of Pharaoh’s daughters and believes her to be compassionate. Jochebed carefully prepares a basket that can float, then lays her son inside, and places it along the banks of the Nile at the very spot where Pharaoh’s daughter comes to bathe. When Pharaoh’s daughter finds the baby floating toward her, she takes the child home and adopts him as her own. Raised in Pharaoh’s household, Moses would have been educated like a prince, learning Egyptian religion, law, and philosophy.

At the age of forty, Moses goes to observe the Israelite slaves, apparently aware that he was born an Israelite. When he sees their mistreatment at the hands of a particular slave driver, his anger wells up, and he ends up killing the taskmaster. When the act is discovered, Moses is forced to flee to the Sinai. He spends forty years there, no longer a prince in Egypt but now a humble shepherd in the vast desert.

Then, at the age of eighty, Moses hears God speak to him from a bush that’s on fire. God says to him, “The Israelites’ cries of injustice have reached me. I’ve seen just how much the Egyptians have oppressed them. So get going. I’m sending you to Pharaoh to bring my people, the Israelites, out of Egypt” (Exodus 3:9–10). With no small amount of resistance, and after exhausting all excuses, Moses does as God commanded. A series of plagues descends upon the Egyptians, and Moses leads the children of Israel to their freedom. He brings them to Mount Sinai, where he first met God in the burning bush, to seek God’s direction. Here God will speak to the Israelites from the top of the mountain, giving them the Ten Commandments.

Thousands of people—or millions, if the Exodus text is taken literally—are camped at the base of Mount Sinai when God begins to speak. They have left behind a familiar life with familiar gods. Although they were slaves in Egypt, they at least had food. Now they’ve risked everything to follow an octogenarian into the barren wilderness, to a place where he claims to have met the God of their ancestors, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Until this day, however, none of them have heard the voice of this God Moses claims to have met.

Standing halfway up the mountain and looking down, it is not hard to imagine their tents and campfires and the hordes of people frozen in terror as they see the smoke and fire bellow on the mountain. Now the God who has delivered them from slavery and who, through Moses, promised them a land flowing with milk and honey, begins to speak:

I am the LORD your God who brought you out of Egypt, out of the house of slavery. You must have no other gods before me (Exodus 20:2).

The Israelites would have known the names of hundreds, perhaps thousands of Egyptian gods. But few of them would have remembered the name of the God of their ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who lived hundreds of years before them. Moses has told the people of this God whom he met in the burning bush. But now God speaks, introducing himself. “I am the LORD,” the text reads in most modern translations, though this is not exactly what the original would have said. The word “LORD,” in all capital letters, is used as a stand-in for the Hebrew word “YHWH”—a word most believe is pronounced “Yahweh,” though some pronounce it “Jehovah.”

While there are many names by which God is called in the Hebrew Bible, this is the most sacred, personal, and at first glance perplexing.2 We first see it in Exodus 3, when Moses meets God at the burning bush. When God calls Moses to go to liberate the Israelite slaves, Moses asks a pointed question:

“If I now come to the Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your ancestors has sent me to you,’ they are going to ask me, ‘What’s this God’s name?’ What am I supposed to say to them?”

God said to Moses, “I Am Who I Am. So say to the Israelites, ‘I Am has sent me to you.’ ” God continued, “Say to the Israelites, ‘The LORD, [Yahweh] the God of your ancestors, Abraham’s God, Isaac’s God, and Jacob’s God, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever; this is how all generations will remember me.” (Exodus 3:13–15)

In Hebrew, “I Am Who I Am” and “Yahweh” are slightly different forms of the same word: the verb “to be.” The name is so important it is found more than 6,400 times in the Old Testament.3 It is so sacred Jews today will no longer pronounce it. (Hence the replacement word “LORD,” which appears in place of “YHWH” throughout the Hebrew Bible.) For reasons I’ll share in chapter 3, I take the name to mean “I am the Source and Sustainer of all that is” or “I am existence itself” or “Everything that exists exists because of me.”

Hear again God’s introduction to the Israelites: “I am the Source and Sustainer of everything. And I am your God. It was I who brought you out of Egypt. It was I who delivered you from your oppression under the Egyptians. I am the one who set you free.”

Embedded in God’s name is the sweeping claim of scripture: Yahweh is the creator of all things. In the beginning, it was he who spoke the worlds into existence and brought forth life on our planet. He formed human beings, writing the genetic code that makes us who we are. Look at the sunshine, the blue sky, the trees, and the animals. These were all his idea. Think of yourself: your capacity to reason and think; your ability to love and to be loved; the expansion of your lungs as you breathe and the air that fills them. All of these things are gifts from God.

That’s what God was revealing to the Israelites when he told them his name. But there was something more he said to them: “I am your God.”

I Am Your God, You Are My People

Anyone who commits to study and memorize the Ten Commandments is immediately confronted with a question: What constitutes the first commandment? Jews order the commandments one way. Catholics and Lutherans another. And Eastern Orthodox Christians and most Protestants yet a third way.

For Jews, the first commandment is “I am the LORD your God who brought you out of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” Christians typically see this not as the lone first commandment but as the prologue or introduction to all the other commandments. For Eastern Orthodox Christians, as well as most Protestants, the first commandment is what God says next: “You must have no other gods before me.”

Roman Catholics and Lutherans go further. They consider the first commandment to be “You must have no other gods before me. Do not make an idol for yourself—no form whatsoever—of anything in the sky above or on the earth below or in the waters under the earth. Do not bow down to them or worship them.”

Since I am a pastor in the Methodist (Wesleyan/Anglican) tradition, in this book we’ll follow the ordering used in my tradition and that of most Protestants and Orthodox Christians. But when it comes to the substance of the text, I think the Jewish people are right in naming the prologue as the first commandment—“I am the LORD your God who brought you out of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” This statement is the premise of all the others. Yahweh is the Source and Sustainer of all that exists, and Yahweh has chosen this ragtag band of former slaves to be his people. Interesting to me, the word “your” used in this verse is singular. God is not just the God of the Israelites, but the God of each of the Israelites.

This would have been a complete reversal in how they related to the gods of the Egyptians. The Israelites may have believed in those gods, prayed to them, and made sacrifices to them. But at the end of the day, these were Egyptian gods. In their providence and will, these gods had made the Israelites the slaves of the Egyptians. The message was clear. To the Egyptian gods, Israelites were second-class, lesser children.

But here was One who claimed to be the source of everything, saying that he wanted Israel and was calling these people his own. In claiming to be their God, he was offering his covenant protection and care to them. These were not empty words, for Yahweh had brought them “out of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.” Of all the people on earth God might have chosen as his covenant people, he chose a people who were slaves, poor and powerless. God chose the Israelites not because of anything that they had done to merit his kindness but because of the promise he had made to Abraham generations earlier. He chose them because of his covenant love and his compassion and mercy.

This theme winds throughout scripture. God often chooses the powerless, the poor, and the pitiable. God does this because his nature is defined by compassion, mercy, justice, and love.

We see it in God’s choice of the elderly Abraham and Sarah, who were too old to have children, to become the parents of a nation. Later, God would bless Ruth, the poor Moabite widow, allowing her to become the great-grandmother of King David. Speaking of David, he was the least impressive of Jesse’s eight sons, yet God chose him to become Israel’s greatest king. The theme is repeated again and again in scripture, reaching its climax in the New Testament when Jesus, whom Christians believe was God incarnate, spent most of his ministry associating with the uncouth, uneducated, unremarkable. He ate with sinners and tax collectors. He ministered to the physically ill, the mentally broken, and the nobodies. Ultimately, he gave his life on their behalf.

The word Christians most associate with this quality of God’s character, this choosing of the unlikely and unworthy, is “grace”—the undeserved love and favor of God extended to us not because of our actions or anything we’ve done to merit it but solely because God is merciful and kind. Saint Paul famously said of God’s saving work in our lives:

You are saved by God’s grace because of your faith. This salvation is God’s gift. It’s not something you possessed. It’s not something you did that you can be proud of. Instead, we are God’s accomplishment. (Ephesians 2:8–10a)

Hundreds of times I’ve had conversations with people who felt they were worthless, insignificant, and unloved, teaching them this truth about God. God knows everything about you. God knows every embarrassing, shameful, or unholy thing you’ve ever done. God knows the things about you that you beat yourself up for: Are you overweight? Unattractive, at least in your eyes? Do you think you are too stupid or broken or unaccomplished or sinful to be loved and valued? God knows all of this, and God still chooses you, sees you as beautiful and gifted, and loves you. God sees not only what you’ve done and who you’ve been but what you can do and who you could be.

I recently spoke with a woman who had been picked on, ridiculed, even sexually abused as a teenager. Her whole life has been spent feeling unworthy of anyone’s love. As we sat in my office, we reflected on this story of how, throughout the Bible, God decides to honor those whom others have rejected, those who believe they are worthless. He has the power to deliver us from our own land of Egypt—the land where we’ve grown up being told that we were worthy only of making mud bricks, stepchildren of the gods. As tears streamed down the woman’s face, she began to understand for the first time that she was beautiful in God’s eyes. She wept as she allowed herself to believe that she was loved, deeply, by God.

This, I think, is what the Israelites understood when they heard these opening words of the Ten Commandments.

What Is a God?

But I also think they were meant to understand that Yahweh was saying, “I am your God.” Which leads to a question that will be important as we consider the first commandment: What is a God?

On the one hand, ancient Egyptians believed that their gods were benevolent forces who created and sustained the world as they knew it. These forces responded to, looked after, and were somehow involved in the affairs of people. As the Israelites were learning, and as Jews and Christians believe today, all of these forces resided in one God who was the Source and Sustainer of everything that exists. This God is just, compassionate, merciful, loving, righteous, holy, strong and mighty, and much more. God sees humans as his children, his workmanship, the sheep of his pasture, his beloved.

In the Hebrew Bible, there are so many powerful images and metaphors describing God, including a sense of God as protector and provider. Psalm 46:1 comes to mind: “God is our refuge and strength, a help always near in times of great trouble.” As the Israelites listened to Yahweh speak, claiming that he was their God, I imagine the sense of peace and gratitude and hope that must have come over them.

As the coronavirus pandemic swept over the world, we all watched as businesses closed, churches stopped holding worship services in person, schools closed for the rest of the school year, and billions of lives came to a standstill as people were ordered to “stay in place.” Amid all of this, millions of workers were laid off. LaVon and I told both of our daughters, “Listen, you are our daughters. You are going to be okay. If you need help in any way, we are here for you.”

We knew our oldest would continue to be paid and work from home. But our youngest, Rebecca, had just opened a small plant shop and worked on the side at a restaurant and bar. Both would be closed indefinitely, and she would have no income. “I know this is scary,” I told her, “but you have nothing to worry about, because we are here. We’re family. Whatever you need, we’ve got you covered.” The feeling of belonging, of being loved, of being protected and safe that I was trying to convey to our daughter is similar to what I believe Yahweh was saying to the Israelites.

Whatever challenges you may be facing today, I wonder if you can hear God speaking these words to you: “I am your God. I am your companion, your shepherd, your deliverer, your safety, your security, your refuge, and your strength.”

No Other Gods

After conveying to the Israelites his name, promising that he will be their God, and reminding them of the deliverance he has already wrought on their behalf, God outlines the terms of his covenant relationship with them. As many have noted, these are not suggestions but religious and ethical requirements governing the covenant relationship between God and his people.

This first commandment calls Yahweh’s people to an exclusive relationship with him. You must have no other gods before me. Interestingly, God does not say there are no other gods. Only that you must have no other gods before or besides me. The Israelites had known and followed a host of other gods. Learning that there was only one God would come later. But here they needed to know only that God had redeemed Israel (a word used to describe purchasing the freedom of another). They no longer belonged to Egypt or Egypt’s gods.

Throughout scripture, the biblical authors use human relationships and emotions to describe God. They compare the love God feels for his people to the relationship between a parent and his children, a lover and his beloved, or a husband and his wife. God is said to be a “jealous God” who is offended if Israel gives her love or devotion to another god. This kind of language seems beneath God to some. But it is helpful to remember that the biblical authors, and God, are using language meant to communicate divine truths in words that mortals can comprehend. Take the language of jealousy, of fidelity and infidelity, for example. As a pastor, I’ve observed on many occasions the pain and heartbreak infidelity causes in marriages. I’ve also seen the pain of parents who were rejected by their children. These are powerful analogies for teaching both the relationship God seeks from his people in the first commandment and the idea that infidelity to God might actually grieve God.

It’s not hard to understand why God would demand an exclusive relationship with his people. When I married LaVon, our pastor asked us if we would be faithful to each other alone “as long as you both shall live.” We’ve spent thirty-eight years fulfilling the covenant we made at our wedding ceremony. In the New Testament, Saint Paul uses the imagery of marriage to describe the relationship Christ has with the church. In the same way, this commandment tells us that God offered fidelity to the Israelites and longed for it from them.

Before considering further this command to exclusivity, it might be helpful to explore the religious context out of which the Israelites had come and the other gods, or suitors, who were vying for their hearts. To that end, I’d like to describe what you would see if you were visiting the great archaeological site of Luxor today.

The Gods of Egypt

Luxor is located 320 miles south of Cairo as the crow flies. Like most major cities in Egypt, it is located on the banks of the Nile. For the first four decades of his life, Moses likely spent most of his time in Luxor, though at the time it would have been known as Waset, the “City of the Scepter.” During most of the New Kingdom period—the time when Moses lived—Luxor served as the capital of Egypt. As he grew up, Moses would have worshipped in the Karnak temple complex and accompanied funeral processions to the Valley of the Kings. If a later date for Moses is presumed,4 he would have walked the halls of the Luxor Temple and Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple.

If you visit these archaeological masterpieces today, you’ll see that the walls and columns are covered with images of Egypt’s most important deities. Often they are accompanied by scenes of the pharaohs bringing offerings to, or being blessed by, the gods. In those days, Pharaoh was considered an intermediary between the gods and mortals, whose offerings and prayers secured the blessings of these same gods. A semidivine being, he ruled over his people on behalf of the gods. If his heart was found righteous at his death, he would enter everlasting life and become a god himself.

Egypt’s god Khnum, center with ram’s head, the god who makes humans out of clay, is joined by Hathor, Horus, and others on a funerary barge carrying Pharaoh on his journey into the afterlife. Photo taken by the author in the Valley of the Kings

The Egyptians believed their deities controlled the natural world. They brought the rains, which in turn brought the life-giving floodwaters of the Nile. They opened a woman’s womb and ensured the fertility of one’s herds and the quality of one’s crops. They brought order to the universe and rhythm to daily life. Most were portrayed with the body of a human and, often, the head of an animal that conveyed some part of the deity’s character or activity.

Walking through the pharaohs’ tombs in the Valley of the Kings or the columned halls of the Luxor or Karnak temples, you’ll see bas-reliefs, paintings, and statues of Egypt’s chief deities. You’ll meet Horus, the falcon, god of the sky. You’ll see Hathor, often portrayed as a cow, who was the gentle goddess blessing humanity with love, sexuality, joy, and dancing. You’ll meet Hapi, who brought the annual flooding of the Nile River—a blessing to Egypt’s agriculture as it covered the earth with its vivifying silt. There is Osiris, god of the underworld, the just judge of the dead. And Isis, Osiris’s wife and sister, who gave protection and wisdom to kings and commoners alike.

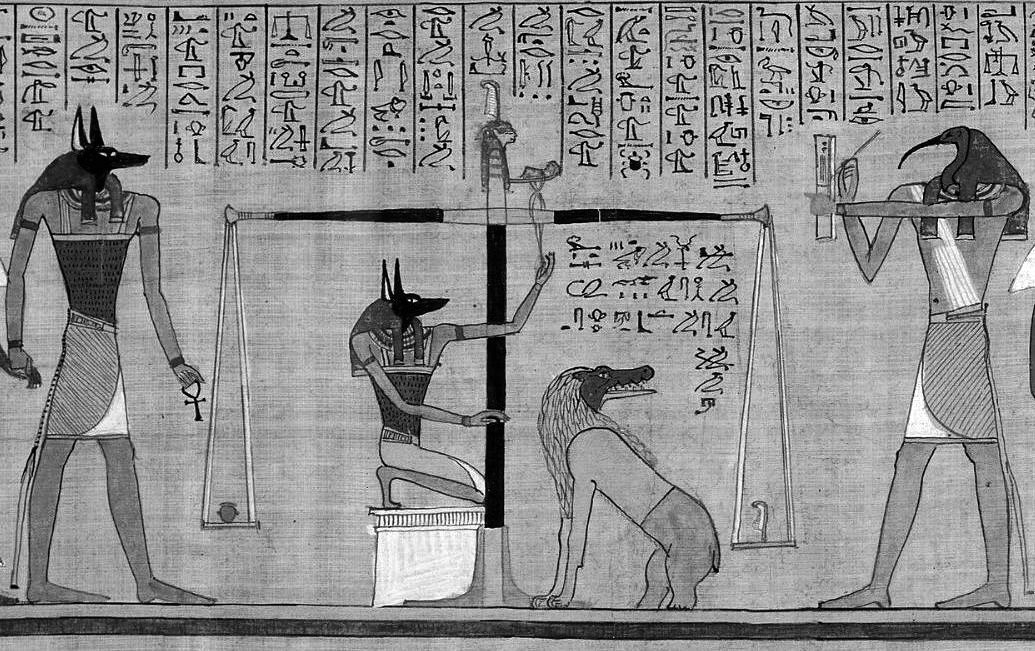

Many of the tombs depict a scene you may be familiar with: the “weighing of the heart” from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. The scene describes the way Egyptians conceived of the final judgment at death. If one was judged righteous or just, a beautiful afterlife awaited. If not, destruction. In these images, Anubis, the jackal-headed god, weighs the heart of the deceased pharaoh against a feather. Maat sits atop the scale. She is the goddess of truth and justice, and she provides the feather. Thoth, Maat’s husband, the god of wisdom and writing, stands ready to record the results. And Ammit is crouched nearby. With the hindquarters of a hippo, the body of a lion, and the head of a crocodile, she stands ready to devour Pharaoh’s heart if it is found to be heavier than Maat’s feather, ending his quest for everlasting life.

The “weighing of the heart” in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

The ruler of all of these gods and goddesses in the time of Moses was the mighty Amun-Ra (also spelled Amun-Re).5 In the New Kingdom period, Amun-Ra was the hidden god, associated with the sun and its life-giving power. Originally worshipped as two separate gods, Amun and Ra, these two deities had been merged into one by the time of Moses. Amun-Ra was the uncreated creator, both powerful and merciful. The Egyptians associated him with fertility and hence often portrayed him with an erection, signifying his role in providing progeny—crops, flocks, and children.

A hymn written to Amun-Ra during the New Kingdom gives a sense of how the Egyptians conceived of him. In it, he is addressed as “Prince of heaven, heir of earth…Lord of truth, father of the gods, Maker of men, creator of animals, Lord of the things which are, maker of fruit-trees, Lord of all things that exist!”6 In a sense, Amun-Ra was to the Egyptians what Zeus was to the Greeks.

Hymns like this give us a sense of the religious devotion the Egyptians had to their deities. It also underscores how Yahweh’s call for the Israelites’ undivided loyalty might have challenged their deeply held devotion to deities like Amun-Ra. Yahweh’s name, I Am Who I Am (I Am the Source and Sustainer), made clear that he, not Amun-Ra, was the Lord of all things that exist.

In that moment beneath Mount Sinai, when the Israelites heard God’s voice and saw God’s power, they were not at all thinking about going back to Amun-Ra. But later, when life grew difficult in the wilderness, when they had forgotten the oppression they’d known in Egypt—or generations later, when life was good and they no longer needed God—they would return to their old habits, the gods they had known in Egypt, or the gods who were worshipped by the nations surrounding them in the land of promise.

Throughout much of the Hebrew Bible, we find the Israelites returning to their worship of the old gods or gravitating toward the gods of their neighbors. The grass is always greener, even when it comes to faith. In the Promised Land, the old gods had new names—Baal, Astarte, Molech, Asherah, and Dagon among them. And the lure of these deities was strong. For hundreds of years after Sinai, the Israelites would succumb to worshipping these Canaanite deities, erecting altars and poles on the mountaintops dedicated to them.

The prophets regularly paint a picture of how painful this was to God. God is brokenhearted at Israel’s infidelity. But I wonder if God’s deeper concern was that he knew the worship of these false gods would ultimately bring his people pain. They were powerless, empty, vapid deities whose paths led away from the Source and Sustainer. Often they led people to act in ways that were abhorrent to God. The apex of such abhorrent behavior was seen on multiple occasions when Israelites, lured by the Canaanite gods, actually sacrificed their own children—burning them alive—in an attempt to secure the god Molech’s help.7 We’ll explore these ancient practices further in the next chapter, as we consider the prohibition against making and worshipping idols.

False Gods We Wrestle with Today

At first glance, all this talk of the ancient gods and people offering their children as sacrifices might seem to substantiate my wife’s argument that the commandments are far removed from our daily lives. Most of us are not tempted to worship Amun-Ra, nor offer our children as sacrifices.

But there is another sense in which the word “god” might be used. It can also mean that which takes the place of God in our lives. The thing that shapes our identity, values, and actions or serves as our source of security and hope. By this definition, we all have our gods, even atheists and agnostics. And by this definition, we all struggle with the first commandment. We are prone to placing the Source and Sustainer of our lives as a distant second to these other gods.

I know people who believe in God but for whom physical fitness has become their true center. Workouts and nutrition plans are what they eat, sleep, drink, and breathe. They devote more money to fitness than to God and spend more time reading about fitness than reading the scriptures. Their devotion to being healthy is admirable, but it can easily become a god that takes the place of God in a person’s life.

Most of these false gods are good and important things that we’ve given our ultimate devotion to. We’ve put too much trust in them, expecting them to do what they cannot do. We’ve placed them on the altar of our hearts, where they were never intended to be.

The first commandment doesn’t forbid passions, hobbies, and interests. It forbids putting them above God, worshipping them and serving them in place of him.

In Philippians 3:19 (New Revised Standard Version) Paul wrote of people whose “end is destruction; their god is the belly; and their glory is in their shame; their minds are set on earthly things.” What an interesting thought, that for some, their god could be the act of eating. Food is a gift from God, and eating too. A lot of Jesus’s best ministry happened over meals, and heaven is described in scripture as a banquet. But I wonder: When do we cross the line from enjoying food to our belly being our god?

Most people don’t notice when they’ve made something a false god. I think of people who spend hours a day on social media. That may be okay, a way of connecting with loved ones who don’t live nearby or of following the news. But at some point, it is possible to become obsessed to such a degree that we have given our hearts to keeping up with social media.

I once knew a man whose love of his job—the corner office, the accolades, and the money—fueled his ego to the point where it edged God out of his life. In the process, it edged out his family too. Caring for his wife and children didn’t boost his ego or make him feel excited and energized like his job did. He found it easier and easier to work the long hours, take the business trips, and skip vacations.

One day, after years of living this way, he came home to find a letter from his wife on the kitchen table. She’d taken the kids and wanted a divorce. I’m not sure the man understood what he’d lost until several years later, when the company decided it no longer needed his services, and he was left alone in his mini mansion in suburbia.

As I reflected on this man’s life, and those children whose father was absent for much of their formative years, I thought about the god Molech, to whom the Israelites sacrificed their children. There are times when our children, grandchildren, spouses, or parents pay the price for our pursuit of our false gods. The man’s story reminded me of the words of Jesus in Matthew 16:26: “Why would people gain the whole world but lose their lives? What will people give in exchange for their lives?”

The Egyptians were said to worship as many as two thousand deities. I suspect we have even more. There are so many false gods to which we might be tempted to give our highest allegiance, our deepest trust. Relationships, clothing, jewelry, success, popularity, health, body size and proportions, image, hobbies, social media, travel, careers, homes, cars, retirement accounts—all of these can become false gods, holding our highest allegiance and having the greatest influence on our thoughts, ideals, and actions. Even our spouse, children, or grandchildren can take the place of God. Good things become distorted and dangerous when we make them the primary focus of our lives.

So many of Jesus’s parables address this same tendency. In the parable of the sower (or the soils), Jesus reminds us that there are some who start off well in the Christian life, but then their faith is choked out like wheat that grows among the thorns. He specifically identifies such people as those who hear and respond to the good news of the Kingdom of God, but “the worries of this life and the false appeal of wealth choke the word, and it bears no fruit” (Matthew 13:22b).

The Bible’s opening story tells of Adam and Eve eating the forbidden fruit. Do you remember how the serpent tempted them to eat the fruit? It wasn’t really about the fruit itself. The temptation came when the serpent told them that if they ate the fruit, they would be like God. The Bible’s first recorded temptation was for humans to make gods of ourselves—pride and narcissism, putting ourselves at the center of the universe. There’s an acronym you may have heard for what happens when we put the self on the throne of our lives. I’ve used the phrase several times earlier: “edging God out.” Notice the acronym: EGO. In the end, the god we are most likely to put before God is the self.

When I began my study of the Ten Commandments, I could think of five or six of the commandments I wrestled with in one way or another, but the first commandment didn’t come to mind. The more I reflected on what constitutes a false god, however, the more I realized that this might be the commandment I am most tempted to break.

We could fill a book just with examples of false gods, and we’ll consider a few more examples as we turn to the second commandment, prohibiting idolatry, in the next chapter. For now, I’d like to end with a reminder of the positive way in which Jesus expressed the essence of this command.

When Jesus was asked what the most important commandment was, he replied not with a prohibition but with a positive mandate: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your mind and with all your strength” (Mark 12:30, NRSV). This is the key to keeping the first commandment. When we love God with all that is within us, we leave no room for false gods.

Loving God and giving our highest allegiance to him enlarges our hearts. It deepens our capacity to love. It transforms our values. It strengthens our commitment. And, by the Holy Spirit’s work in us, it results in what Saint Paul called the fruit of the Spirit being produced in us: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, gentleness, and self-control. Qualities like these will help us love our spouses more, for example, than if we placed our spouses above God.

This is true of every part of our lives. As we place our trust in God and seek to love him with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength, we become more likely to love our neighbor, to do what is right and just, and to experience the good and joyful life. This commandment is the key to fulfilling all the rest.

I wonder, if God is not in your life, then what is at the center of your life? What are the false gods you are tempted by? The otherwise good things to which you are tempted to give your highest allegiance, your deepest trust? The things in which you might be tempted to seek your greatest security, to which you might be tempted to devote your time and talent above all else? What, if not God, is the greatest influence shaping your values, ideals, and behavior?

I recently spoke with the CEO of one of the largest hospitals in Kansas City. I told him I had been reflecting on this commandment and what it says about our deepest commitments, what we trust in, what drives us, and our identity. He said, “In my work, the people who walk through our doors at the hospital are usually sick, except those giving birth. And when they are sick, they begin thinking about what really matters. The sicker they are, the less things they thought were important matter. And for those we cannot heal, for whom death draws near, there is only One who remains, in whom they can find hope. I think that’s why he calls us to have no other gods before him.”8

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said to people whose lives were consumed with worry about things like what they would eat and what they would wear, “Desire first and foremost God’s kingdom and God’s righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well” (Matthew 6:33). “Desire first and foremost” is a great way of expressing what this commandment calls us to.

When we desire him, his kingdom, and his will first and foremost—when we love him with all that we are and prioritize our faith in and service to him above all else—our capacity to love others grows, our peace and joy increase, and we find life.

What Jesus Might Say to You

My Father says to you, I am your God. I have delivered you in the past and will deliver you in the future. I have loved you as a parent loves a child, as a selfless spouse loves their beloved. I want you to have no other gods before me, because when you make something else your god, you are diminished, not enriched. If you love me with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength—if you seek first my kingdom—you’ll find so much more than if you’d made something else your god. I plead with you, have no other gods before me.