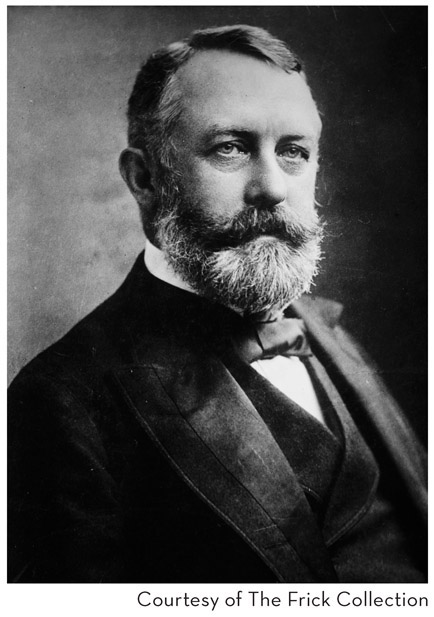

The Frick Collection on 5th and East 70th Street is one of the most impressive private art museums in New York, if not the world. Named after industrialist Henry Clay Frick whose personal art collection was the nucleus of this collection, the museum was built first as his family’s personal residence then after his death became a museum.

Not only did he amass one of the greatest art collections in the world, his former home is the epitome of the Gilded Age. Built in 1914, it is a monumental work of art with hand cut marble, among the flourishes. With its open center garden court and seemingly endless cavernous rooms, some with grandiose themes, it is easy to forget this was once a home.

Though all this opulence and beauty continues to impress visitors today, some would be equally impressed, perhaps even shocked, to know the place also features a bowling alley.

Yes, with all its priceless works of art, austere decor and manicured grounds, the basement has a bowling alley. As one would expect this is not one’s neighborhood bowling alley where a couple of guys come in to sling some balls and drink beers. Along with the rest of the home, the alley and subsequent recreation room is exquisitely executed and designed as one would hope when a gilded-ager gets their hands on a popular sport.

Tightly fitted into a small space, the two lane alley made by the Brunswicke-Balke-Collender Company features ornate vaulted plaster ceilings, and carved mahogany-paneled walls. There’s also a billiard room nearby done in equally careful execution and luxury.

Like many bowling alleys, the lanes are constructed of maple and pine, and for its era do not feature set up machines for the pins. Instead servants stood by and put the pins up by hand.

The original bowling balls are still here, made of a Bakelite composite common for the time, and with only two holes, not three for the bowlers’ fingers.

The ball return is especially unique with its carved flourishes and ornate posts. Again no automation here, just good old fashioned gravity and physics to return the balls. A chalkboard off to the side was used for keeping score.

Frick himself was a stickler when it came to recording household costs. Luckily for the museum curators, for they have all the receipts for building and maintaining the bowling alley. The alley cost a princely $850 dollars to build with the balls costing an extra $100.

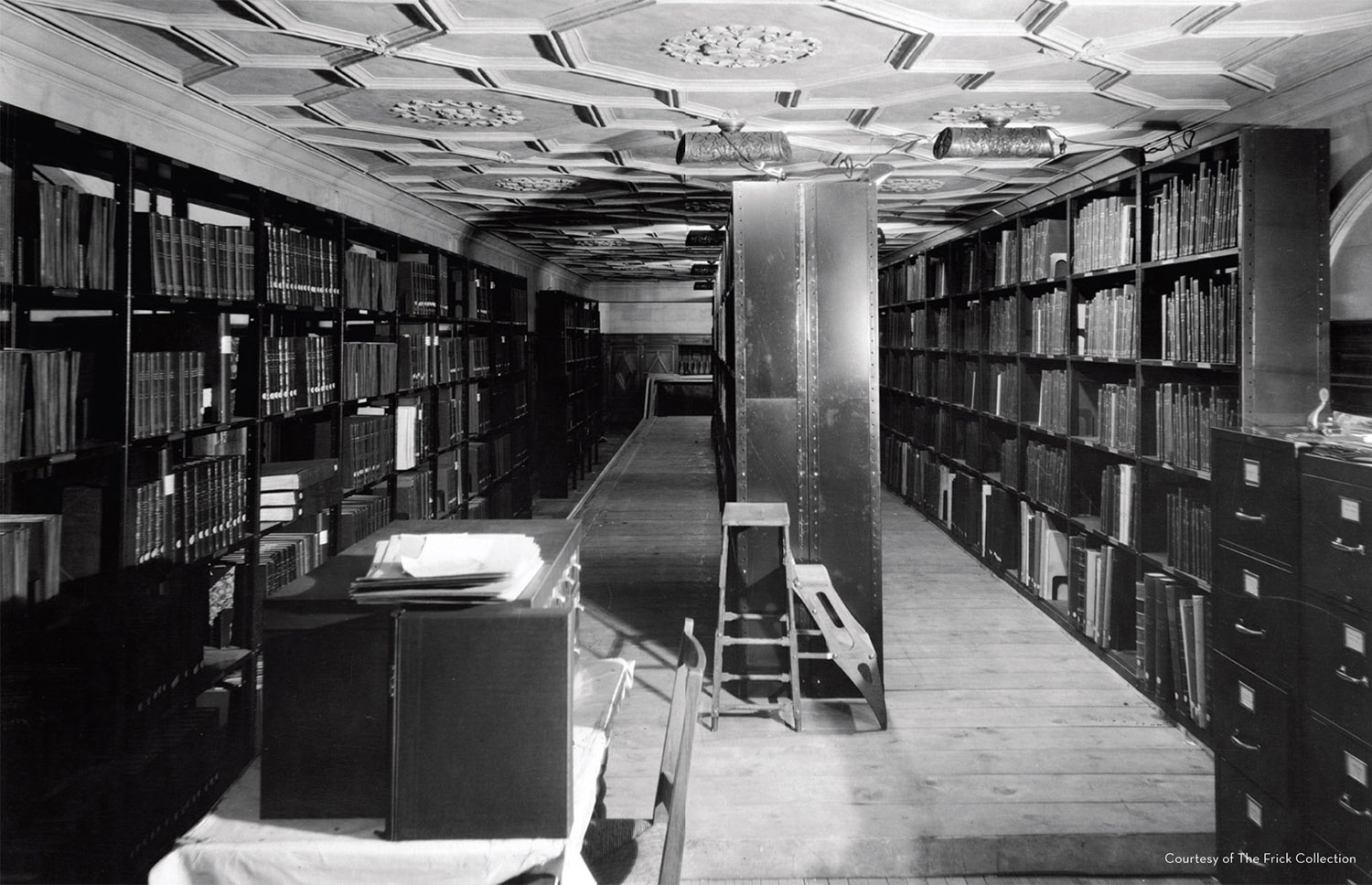

Henry Frick died in 1919—only giving him a few years to reside here. After his death, his daughter Helen Clay Frick took over the home and created what was first called the Frick Art Reference Library. Her life’s work was amassing numerous books and documents for the museum from the United States and Europe. As the collection grew she began running out of space to store the items and the bowling alley became storage for the collection.

That very well may have saved the alley’s originality before it was restored in 1997, the space had remained virtually untouched, inadvertantly sealed from the changes of time. It is pretty much the status of the bowling alley today. Frick administrators say due to the fragility of the interior and lack of fire exits, they cannot open it to the general public. There is however a workaround. According to their website, donate $5,000 as a “Supporting Fellow Level” and you’ll get the privilege of seeing the alley up close and personal. Mister Frick would probably crack a smile about that.

HENRY CLAY FRICK

Though his taste in art was exquisite, Henry Clay Frick was not the necessarily the most well-liked person. In fact, Frick had the dubious honor of being once labeled “America’s most hated man” partly due to his anti-union actions.

Frick made his fortune in steel and coal. When he partnered with fellow financier Andrew Carnegie, together they built the Carnegie Steel Company into one of the largest steel companies in the world. Frick would go onto help build the United States Steel Company.

But Frick’s reputation will always have a blot due to the infamous Homestead, Pennsylvania Strike in 1892. The Carnegie Steel Company was in a bitter labor dispute with its workers. The strike came to a violent head, when Frick hired 300 strikebreakers—armed agents from the Pinkerton Detective agency—to essentially invade the mill. An all out battle ensued leaving ten killed and sixty wounded. The country was outraged calling it a massacre and vilifying Frick. An anarchist even tried to assassinate him, shooting Frick twice and stabbing him multiple times. Incredibly, Frick managed to be back at work in a week.

The Homestead Strike followed Frick for the rest of his life and contributed to the downfall of his friendship with Carnegie. Years later, when Carnegie was near death, he requested to meet with Frick to which Frick responded in note, “Tell him I’ll see him in Hell.”

Actually known as quiet and reserved, Frick was perhaps not as purely ruthless as he is often depicted. When he died in 1919, he left a staggering fifty-million dollar fortune. Five-sixths of it was donated to charity.