Short Skirts, Long Beards

‘We live not according to reason, but according to fashion’

Seneca, Roman philosopher, mid-first century AD

In matters of supremacy and conflict it is, as the saying goes, the one who ‘wears the trousers’ who usually has the upper hand. For centuries wearing ‘braise’ or britches has been a masculine prerogative affording the wearer vital ease of movement both in battle and physical work, something denied to women until emancipation in the early twentieth century. However, once in our history the opposite was true. When the Romans invaded our shores in the first century AD it was not only their weapons that won them this island. As every victory in history has relied as much on psychology as strategy there is no better illustration of mind over matter than the Roman belief in himself. Thus, his armour atop his customary short tunic gave him, in his mind, that vital ‘edge’.

Relief panel of the Great Ludovisi sarcophagus showing the battle scene between skirted Roman soldiers and a heathen enemy in trousers. From a tomb near the Porta Tiburtina, it dates from AD 250–60. (Author’s collection)

The Roman way of life was totally alien to those living in the far-flung outposts of the Empire and the culture of the ‘trouser-wearing’ Britains spoke to the invader in volumes. ‘Trousers’ were the dress of heathens. As ‘skirted’ and ‘clean cut’, the Roman thought himself superior, a natural overlord whose rightful duty was to take our island from those they saw as subordinate. In reality, that idea that ‘men in skirts’ could actually have the decisive advantage is as unlikely today as it was then, but the Roman ethos of cleanliness in both body and dress elevated them in their own minds above the unclean, long-haired, bearded and trouser-wearing islanders. Once convinced, the Romans were nothing if not confident and as such pulled off one of the only two invasions of Britain.

This scenario is a perfect example of how ‘clothes maketh man’; how they define him and how what you wear is as important as what you wield. Self- belief certainly elevated the Roman soldier, in his own mind at least, above his equally formidable foe. Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian writing about the Celts of Gaul and Britain in the first century, described the Roman opponent as tall and ‘terrifying’ with ‘rippling muscles under clear white skin. Their hair is blond, but not naturally so: they bleach it, to this day, artificially, washing it in lime and combing it back from their foreheads. They look like wood-demons, their hair thick and shaggy like a horse’s mane.’ Their costume he described as ‘astonishing’, adding that they wore ‘brightly coloured and embroidered shirts, with trousers called braccae and cloaks fastened at the shoulder with a brooch’, this latter garment heavy in winter, but light in summer. Striped or chequered in design, such cloaks had ‘separate checks close together and in various colours’, proving perhaps the Dark Ages were perhaps not so dark after all. Such were the British enemies of Rome dressed, with trousers available even to women. This was another reason the Romans shunned what they saw as female garb. In doing so it prevented them from wearing what they considered made them look ‘more the heathen, than the elect’. Not about to surrender his native Mediterranean clothing even in the face of the freezing mists of Albion or snows of a Hibernian winter, the common soldier did have tried and trusted cold-weather clothing in the form of cloaks, socks, leg wrappings or bindings called puttees which wrapped from the ankle up to the calf, extra tunics and scarves which went some way to making life in this furthest outpost of the Roman Empire at least bearable. If not, supplies could be requested from Rome, as details from Tablet 255 of the Vindolanda Tablets, discovered in the 1970s and 1980s, disclose:

Clodius Super to his Cerialis, greetings. I was pleased that our friend Valentinus on his return from Gaul has duly approved the clothing. Through him I greet you and ask that you send me the things which I need for the use of my boys, that is, six sagaciae, n saga, seven palliola, six [?] tunics, which you well know that I cannot properly get hold of here. May you fare well, my dearest lord and brother … To Flavius Cerialis, prefect, from Clodius Super, centurion

As the Romans assimilated into their new homeland eventually the braccae were worn by artillery soldiers in the coldest outposts but renamed ‘femoralia’, and were usually dark red and of varying lengths tied at the waist. Roman dignitaries, however, never stooped to wearing trousers and continued to wear the traditional toga over a tunic. Near the end of the Roman Empire the Emperor Honorius (d. 423 BC) prohibited men wearing ‘barbarian’ trousers in Rome, but insisted all Roman prisoners wear the heathen garment as a sign of their subjugation.

Keen to further establish themselves both in Rome and in Britain, the average Roman underlined his superiority by remaining clean-shaven, though beards were allowed to be worn by those of very high rank as a venerated mark of manhood. Across the Mediterranean the first shaving of a young man was done with the greatest ceremony and these ‘first fruits of the chin’ were carefully collected in a gold or silver box, in order to be afterwards presented to some God, as a tribute of youth. This recognition of manliness was something that carried through to later centuries, with the founder of the Holy Roman Empire, Otto the Great, allowed to ‘swear by his beard’ on important matters, as well as the early Kings of France, for greater gravitas, including three hairs from their beard in the seals on their letters. Even England’s Tudor chancellor, Thomas Moore, about to be executed on the scaffold, elevated his beard’s importance in the eyes of those watching him. When laying his head on the block he moved it out of the path of the executioners axe apparently saying, ‘My beard has not been guilty of treason; it would be an injustice to punish it.’ It was this almost religious reverence for the beard that prompted the Romans to forbid the wearing of them by enemies, slaves or those deemed unworthy. This was to be the greatest cause of shame to a conquered people as the celts of Britain were nothing if not extremely hirsute.

With more than enough hair to spare, both the male and female Celt wore theirs long in multiple elaborate braids, sometimes with gold ornaments fastened to the end of them. A legendary tale tells of one woman having three braids of hair wound round her head, and the fourth hanging down her back to her ankles, though it is more likely to be folklore than fact. However, for a people that embraced an abundance of hair as outward signs of both masculinity and femininity to have their chins shaved and their hair shorn was the greatest affront and disgrace a heathen could receive. For the Romans it was the perfect way by which to subjugate their enemies. Not until women willingly cut theirs as a symbol of emancipation did hair became less status symbol and more fashion statement. But that was going to take upward of a thousand years and before that the Romans would have long left our shores and the British provinces reduced to Saxon rule.

Stepping into the void left by the Romans it was inevitable that the new Germanic overlords had their own rules and regulations for hair. Just as it had been for the preceding Celts, hair was a symbol of virility and strength. It was expressive. Framing the face it was easily visible and easily subject to change; it could be dyed, shaped or worn loose. Longer hair meant high birth and again like the Celts, denoted a free man. It was a visual and social badge of a warrior aristocracy. For the Saxons their hair was protected by law with penalties if the law was broken. It was forbidden to seize a man by the beard and tear any hairs from it or from his head. By the laws of King Alfred it was against the law to cut off a man’s beard and if such happened he was entitled to 20 shillings compensation. If a long-haired boy had his hair cut without his parent’s consent, the wrongdoer would be in receipt of a very heavy fine. The same applied for cutting the hair of a freewoman. Even to snatch a head-covering from her head was an offence.

With British Christianity still in its infancy in the eighth century, the Venerable Bede spoke of a man’s beard ‘as a mark of the male sex and of age, and is customarily put as an indication of virtue’. However, on Ash Wednesday 1094, when the religion had taken a deeper hold, Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury refused to give his blessing to men who ‘grew their hair like girls’. At Rouen two years later, a church council decreed that no man should grow his hair long but have it cut as a Christian. Just prior to William of Normandy’s invasion of Britain thirty years earlier, the Saxon King Harold sent spies into France as – should an invasion take place – he wished to know what a Frenchman looked like in order to distinguish them from his own men on the battlefield. On their return the spies reported back that all the Norman soldiers were ‘surely priests as each had their entire faces, plus both lips shaved’, this at a time when it was customary for the English to leave their own upper lips ‘uncut’. Such observations are indeed borne out by the Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered record of the subsequent invasion, as it shows the English with moustaches and long hair; the Normans are short-haired and clean-shaven.

Facial hair was also an issue with men of holy persuasion. The Benedictine monk Orderic Vitalis (1075–1142), who was reputed to be an honest and trustworthy chronicler of his times, when referring to the court of William Rufus (1087–1100), the third son of William I, wrote that a man’s long hair suggested dubious morals and made him crazy and prone to ‘revel in filthy lusts’. Bishop Ernulf of Rochester (1114–24) detested how some men with long beards ignored the fact that they inadvertently dipped them into their drinking cups, while an earlier bishop, observing how some hermits and holy men did not shave or cut their hair, made the derogatory remark that ‘If a beard makes a saint, nothing is more saintly than a goat’. William of Malmesbury, being particularly scathing about aristocrats with long hair, cited it as a sign of homosexuality and decadence. He even blamed the English defeat at the Battle of Hastings on it as he said it led men who should have defended their kingdom with much more vigour to behave no better than women.

The beard was a sign of veneration in many cultures and to remove it forcibly was a punishable offence. Detail of a miniature of Dagobert cutting his tutor’s beard, from the Grandes Chroniques de France, France (Paris), 1332–50. (British Library digitised manuscripts)

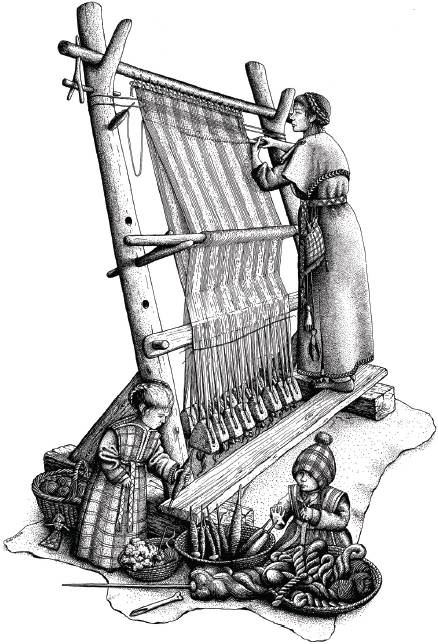

But whatever went on about a man’s chin the clothes on his back were not as easy to come by. Whereas today we easily buy clothing and our recent ancestors were at least able to obtain the ready-made fabrics by which to make them, earlier in history it was case of having to cultivate sheep, the source of your clothing in the first place. Anglo-Saxon and early medieval clothing was woven out of linen or wool, with the earliest sheep being mostly brown and grey. After sheep were domesticated, more native white sheep were bred in order to produce more white wool which was thought easier to dye. British wool was far superior to that of other countries, due to the cool, wet climate and longer grazing season. This in turn produced long fibres which resulted in a finer, stronger thread. Wool was then shorn from the sheep, sorted, scoured, combed or carded and then spun, usually using a drop spindle. Once spun into thread it was woven more often than not on a warp-weighted loom. Such looms were the mainstay of all fabric production and produced anything from simple cloths to intricate tapestry work. Looms also varied in width with some able to make fabrics almost 2m wide with the weaver walking back and forth while weaving, alternatively two or three women would sit side by side and pass the shuttles forwards and backwards between themselves. Card weaving (or tablet weaving) was used to make belts, trim and fringes. Anglo-Saxon and Viking crafts also included a netting technique called sprang, which like an early form of knitting was used to produce caps, bags and stockings.

An Iron Age loom. (© Sue Walker White)

Once woven the fabrics were sewn into clothing using woollen thread and with needles originally made of bronze but later of steel. Needles themselves were extremely valuable, varying in worth from a yearling calf for a common needle to an ounce of silver for an embroidery needle. Just like today, all seams were on the inside of the garment except for those made of leather which were sewn on the outside for better weatherproofing. Double-layered winter cloaks were constructed of heavy wool, the outside also weatherproofed by oiling. Inside, as lining, there was usually a layer of smooth linen of a bright, single colour laying to rest the misconception that all Dark Age and Early English clothing was dull and drab.

A mastery over the art of dying meant that up until and beyond the High Middle Ages English men and women were clothed in colours of almost every hue. Well-practised but not always fully understood, it was both revered and treated with suspicion, especially on the domestic front. For many it was considered a strange and magical process, with rules about which days of the week or month were proper dyeing days, with dyers also having a reputation for being herbal healers, since many dyestuffs were also used in folk medicine. Ultimately, dyeing was considered a woman’s craft, there being an air of taboo about carrying out the ‘alchemistic’ practice in the presence of men. In an ancient Irish text called the Book of Lismore a passage recounts the moment when St Ciaran’s mother tells him to go out of the house, since it was unlucky to have men in the house while dyeing cloth. In a fit of pique he left but not without cursing the cloth so that it dyed unevenly.

One ancient word for dyestuffs is ‘ruaman’; the word ‘ruam’ meaning red, a colour obtained from the madder plant, indicating that most dyes were sourced from plants, roots and vegetables. Yet no fibres, thread or fabric would keep its depth of colour if not ‘fixed’. This was done with a ‘mordent’, a French word meaning ‘to bite’, which helped the dyes penetrate the fibres instead of simply lying on the top and being easily washed off.

Varied and interesting, mordents were naturally occurring and when mixed with the dye not only stopped colours fading over time but also added to their depth. Popular mordents were iron, which could be obtained from ore and was known to ‘sadden’ colours or make then greyer, as did oak-galls, otherwise growths on plants. Copper, or the bluish-green patina formed on copper by oxidation and known as verdigris, was common, as well as alum, a sulphate obtained from wood ash, chips of oak or alder wood. In order to fix and ‘brighten’ colours the favourites were burnt seaweed or kelp and lastly urine, which was readily available and collected by women in the mornings and left to grow stale to increase its strength and potency.

Colours themselves were taken from the roots, leaves, flowers or bark of plants with different parts of the same plant often yielding different hues. Lichens were a favourite as they produced ‘fast’ permanent dyes and if gathered in July and August and dried in the sun, could then be fermented with stale urine, sometimes for as long as three weeks over low heat, to dye wool in an iron dye-pot. Yellow, with a mordent of alum, could be obtained from the barks of birch, ash and crab-apple trees. Wood and leaves of the poplar, the young roots of bracken, bramble and broom, onion skins, nettles, moss and marigold were just as effective in creating yellow, as were heather, dogwood and common dock leaves. Teasel, water pepper and the flower heads of St John’s wort, if soaked in ammonia (urine) for several days, did the same. A plant called weld yielded a light, clear yellow, as did meadowsweet sorrel, gorse blossoms and mare’s tail.

Until 1498, when Vasco da Gama opened a trade route from India to Europe to import indigo, blue was commonly produced by fermenting woad leaves. Blackthorn, privet and elderberries could also be used, while bilberries and the roots of the yellow iris if fixed with iron also produced blue. Mud boiled in an iron pot would produce a very colourfast dull, black dye, the mixture able to produce a glossy black if oak chips or twigs were added. Brown could be obtained by using birch, bog-bean, briar and bramble roots. Dulse, otherwise known as seaweed, also produced various shades of brown, as did hops, larch needles, speedwell and lichens mixed with iron in a dye-pot. If green was required then foxgloves, flowering rush, the crumpled buds and leaf fronds of bracken, horsetail, nettles and privet berries would work. If a really dark green was desired then mixing weld with sheep dung gave a good depth of colour not to mention smell. Pinks and reds were derived from madder roots and a dyer could produce a whole spectrum of shades from coral to rust by skilfully raising the temperature of the dye vat by a few degrees. Blackthorn in a mordent of alum produced orange. Lady’s bedstraw and cudbear lichen mixed with ammonia was the means of getting crimson.

The most highly valued, and noblest, colour of ancient times was purple. Like other colours, various shades could be produced from plant dyes such as dandelion, deadly nightshade, spindle, the flower heads of St John’s wort and the berries and bark of the blackthorn. However, the strongest shade of purple was derived by using molluscs such as murex.

Purple was first produced in or near the city of Tyre in Lebanon during the Roman period. According to Pliny the Elder’s book Historia Naturalis, the process was a long and laborious business involving whelk mucus, honey, salt and water, and long-term heating in a lead vessel. Those who invested their time and effort in its manufacture came to be known as ‘purple-makers’. Probably the worst aspect of the job was the smell. The tiny shellfish first had to be crushed down (on average 1,000 shellfish would yield enough dye for colouring one cloak) then put into water. After ten days fermenting the liquid was full of pigment and wood ash was added for alkali, then the whole stinking concoction was left again to rot down, well covered to keep out light. This was essential as light would strip out the red in the liquid and resulted in the dyer being left with a pot of ‘blue’ not ‘purple’. At the end of a prescribed time there was no other way of ascertaining if the light blue dye you had was ready than first to feel it to test its alkalinity (smooth if done, rough if not) then, if still unsure, to taste it. Once satisfied a strip of cloth or linen was soaked in the dye for half an hour after which it was taken out and exposed to the air. It is at this point, finally, at the end of the long and smelly process that a chemical reaction took place and the material, at first still white, after a few minutes changed to a watery green before transforming to the deep and vibrant colour purple so sought after.