Sumptuous Stuarts

‘Be it resolved that all women, of whatever age, rank, profession, or degree; whether virgin maids or widows; that shall after the passing of this Act, impose upon and betray into matrimony any of His Majesty’s male subjects, by scents, paints, cosmetics, washes, artificial teeth, false hair, Spanish wool, iron stays, hoops, high-heeled shoes, or bolstered hips, shall incur the penalty of the laws now in force against witchcraft, sorcery, and such like misdemeanours, and that the marriage, upon conviction, shall stand null and void.’

Bill from the British Parliament, 1690

With the death of Elizabeth I the age of Gloriana began to fade. The wondrous era of power and prestige was giving way to the more circumspect reign of a dour king with fashions changing little during the opening decade of the seventeenth century. Elizabeth’s fashions, at least for women, persisted for a time beyond her death as ladies, who took their cues from royalty, were to see the old queen’s nephew James I give over the whole of her late majesty’s huge and costly wardrobe to his wife, Anne, upon his succession to the throne. This was for Anne, as with any woman, to prove a mixed blessing, for as reluctant as she was to receive cast-offs (albeit those of a queen), Anne knew her husband for a parsimonious individual and was often kept short of her clothes allowance. Elizabeth’s wardrobe inventory, however, proved the garments were no mean gift as it was said she had 102 French gowns (gowns with a slight train in the back), 100 loose gowns (gowns worn in private chambers without a corset), 67 round gowns (gowns without trains), 99 robes, 127 cloaks, 85 doublets, 125 petticoats, 56 safeguards (outer skirts), 126 kirtles and 136 stomachers.

Female dress still enthusiastically embraced the farthingale, which although a mode of dress accepted by all in the Western world apparently still produced surprise in far-flung corners of the globe. An entry in a book by John Bulwer, an English physician and philosopher, called A Pedigree of a Gallant recounts how James I upon sending his envoy, Sir Peter Wyatt, as ambassador to Constantinople also allowed his wife to accompany him, her gentlewomen, in turn accompanying her. On their arrival the wife of the Sultan wished to meet the ladies from across the sea and arranged an audience. Lady Wyatt clearly surprised the Sultaness with her huge and decorated appearance and was asked to explain her costume, as it was clear the Sultaness had never seen women dressed like that before. It was a strange phenomenon and the author went on to explain that whereas Eastern women have always followed ‘a simple ideal of dress’ and had never ‘wandered into the follies and distortions of the European ladies’, it was, however, the ladies of the European world who despised their Eastern neighbours.

The period was also a turning point for the wearing of ruffs and bands. These quickly fell out of favour as the reign continued, especially those, and there were many, that were stiffened with yellow starch. This can be attributed to a particular incident, the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury. It was not he that wore the ruff in question but a Mrs Anne Turner, a milliner’s wife of Paternoster Row, who as an accomplice to the Countess of Somerset (herself pardoned due to high-ranking connections) was complicit in the crime. When Anne was hanged at Tyburn she was wearing a yellow cobweb-lawn ruff.

Anne of Denmark (1574–1619), wife of James I, who inherited a large part of Queen Elizabeth I’s wardrobe. The painting, attributed to John de Critz, c. 1605, shows her wearing a wheel or drum farthingale. (Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

Fashion at this time was no less ‘complicated’ than it had been before except now there were no longer any sumptuary laws. In 1604, a year into King James’s reign, Parliament had decided against all further statutes of apparel, thinking all men perfectly able to dress themselves accordingly, preferring to issues royal decrees if there was a need to curb extravagance or for political reasons, but these were few and far between. It was thought in this new and forward-thinking seventeenth century that sumptuary legislation was rooted in the Middle Ages and that there was no longer a great need for such medieval fondness for regulation. Perhaps the legislators had learned that such laws were very difficult to enforce, that it interfered too much with daily life, was oppressive and therefore liable to stir up discontent. Certainly, the demise of the sumptuary law could not be attributed to any decrease in extravagance, or by the disappearance of fantastic fashions. On the contrary, as far as britches were concerned they continued to be stuffed and displayed as they had in Elizabeth’s time, giving rise to a satirical ballad entitled ‘a Lamentable Complaint of the poore Cuntrye men, agaynste great hose, for the loss of their cattelles tales’; horsehair, and anything else that was handy, seems to have been used to stuff these capacious garments.

Perhaps as a result of the new dress freedom, overdressing became quite common.

In a sermon preached at Whitehall on the occasion of the marriage of Lord Hay (6 January 1607) the preacher, Robert Wilkinson, used the occasion to voice his own thoughts on women’s fashion to a captive audience:

Of all qualities, a woman must not have one qualitie of a ship, and that is too much rigging. Oh, what a wonder it is to see a ship under saile, with her tacklings and her masts, and her tops and top-gallants; Yea, but what a world of wonders it is to see a woman … so … deformed with her French, her Spanish, and her foolish fashions, that he that made her, when he looks upon her, shall hardly know her, with her plumes, her fannes, and a silken vizard, with a ruffe like a saile, yea a ruffe like a rainebow, with a feather in her cap like a flag in her top, to tell, I thinke, which way the wind will blow.

As if to add weight to Wilkinson’s tirade, one playwright, who employed twelve maids to dress the young boy who was to play a female lead in his production, similarly observed and could not believe the rigmarole and time it took to make the lad ready:

Such a stir, with combs, cascanets, dressing purls, fall squares, busks, bodies, scarfs, necklaces, carconets, sabatoes, borders, tires, fans, palisades, puffs, ruffs, cuffs, muffs, pushes, partlets, ringlets, bandlets, corslets, pendulets, armlets, bracelets … and also fardingales, kirtles, busks, points, shoe ties, and the like, that seven pedlars, shops, nay all Satrbridge Fair, will scarcely furnish her. A ship is sooner rigged by far than a gentlewoman made ready!

Barnabe Rich, another contemporary writer, commented in his Honestie of this Age in 1614 that seeing women going to church ‘so paynted: periwigd: poudered: perfumed: starched: laced, and imbrodered’ it was difficult ‘to distinguish between a good woman and a bad’.

Fashion, during the Stuart era would evolve quite distinctly no less than four times with early styles still stiff, tight and heavily embellished. By 1620 clothing was becoming softer, less structured and comparatively more comfortable. Padding on both doublets and bodices disappeared and upstanding ruffs were replaced with falling bands sometimes known as Bertha collars. Waistlines both on men’s and women’s garments rose as did women’s sleeves, allowing more flesh to be seen first at the wrist then the entire forearm.

With the death of James I English fashions mirrored those of France, most likely due to the fact that the new King, James’ son, Charles I, had married the French Princess Henrietta Maria. Before long the stiff formality of the Spanish, which had influenced our clothing since the arrival of Catherine of Aragon and her vardingale, gave way to the subtlety and freer styles of Paris and Versailles. Unfortunately, not all saw this as liberating or welcome with an anonymous contemporary writer declaring that to his mind his fellow countrymen had turned ‘French apes’, and wore nothing but French styles: ‘Wee are so disfigured by phantasticall end strange fashions that wee can scarce know him to daie, with whom wee were acquainted yesterdaie.’ He also pointed out that ‘some in the midst of winter wore doublets so cut and slashed that they could not keep in the body heat or keep out the rain!’. It was also commented upon that women frequently cut their dresses so low that their breasts and shoulders were practically entirely uncovered. This was considered ‘an exorbitant and shameful enormity’ which was prejudicial to the health, ‘as by exposing too much to the cold, so that some of them lost the use of their hands and arms’. Not all females, it transpired, succumbed to this fashion, it apparently being only the plump and buxom who liberally displayed their bosoms. For those who were lean and far less well endowed it was equally noted that they went ‘muffled up to the throat’.

With French cities now the leading producers of luxury goods, the fact they rigorously exported their silks and brocades did much to expand their influence. One such luxury item that was to epitomise the seventeenth century, whether made at home or across the Channel, was lace.

Lace – ‘She herself has told me that lace is worn in hell’, Don Quixote

The English word lace is derived from the Latin word lacis, meaning noose. Whereas Tudor lace was predominately ‘net’ lace, fashionable laces of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries used bobbins or needles to create the intricate and fine web-like patterns. Aristocrats mortgaged estates for the want of it, just as the poor laboured, often by candlelight, to produce it. Smugglers risked their lives to obtain it, while women and children were transported to worlds beyond the seas for stealing a handkerchief’s worth.

Adequate lighting was an important consideration in lace-making. In summer the cottagers could work outside, but at night and during the winter work was done by candlelight, which could be magnified by putting water into a glass vessel and shining a candle through it. Also in winter, to keep warm, ‘fire-pots’ were used. Women could not sit near fires because the smoke would dirty the expensive lace thread, so earthenware vessels pierced with holes and filled with hot ashes or glowing charcoal, were placed near their feet or tucked beneath their voluminous skirts.

Sometimes lace-makers would work in the lofts above cattle byres in winter. Heat generated by the bodies and breath of the animals stabled below would rise and help keep the workers warm. Even in such primitive conditions good workers would keep their hands scrupulously clean in order not to soil the lace and so lower its value.

Like a finely spun cobweb, lace became an integral part of the second fashion change to take place in the seventeenth century, namely the Cavalier period which began with the reign of King Charles I of England in 1625. In 1651 Jacob Van Eyck wrote:

Of many Arts, one surpasses all. For the maiden seated at her work flashes the smooth balls and thousand threads into the circle, and from this, her amusement, makes as much profit as a man earns by the sweat of his brow, and no maiden ever complains, at even, of the length of the day. The issue is a fine web, which feeds the pride of the whole globe; which surrounds with its fine border cloaks and tuckers, and shows grandly round the throats and hands of Kings.

Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I, by Anthony Van Dyke, c. 1632–5. (Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

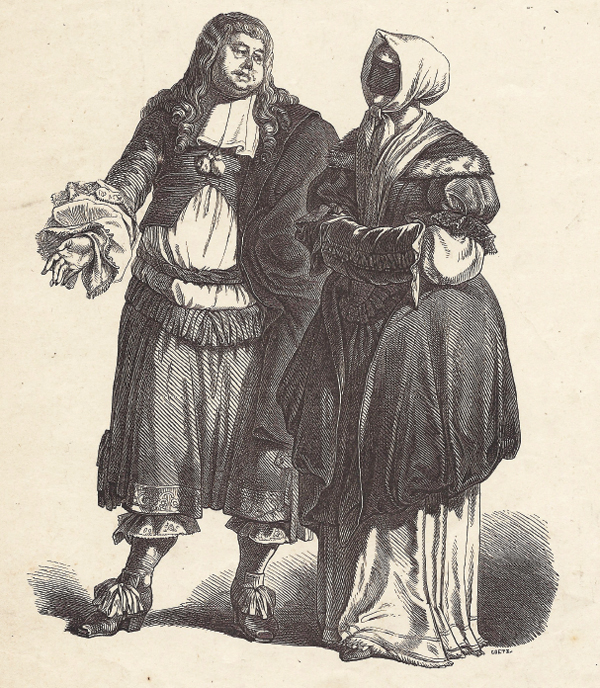

Lace and flamboyant costume were the trademarks of the Cavaliers. Antique print. (Author’s collection)

Lace adorned everything – collars, cuffs and stocking tops – and soon became a most valuable commodity. It created a lucrative trade for the smuggler, who had been known to ‘import’ it into the country in objects as diverse as corsets and coffins. While the new lavish clothing styles were adopted by some, others rejected the excessive ornamentation in favour of more restrained styles. But clothing styles during the seventeenth century were not merely about looks; a person’s choice of clothing also told the world about his or her religious or political positions with the Cavalier style soon associated with the Catholic religion and a strong king. Those that wished to throw off the monarchy and become a republic favoured the Roundhead cause, and in keeping with their Protestant religion dressed themselves with less flamboyance. Yet, the more circumspect in society recognised the effort it took to make lace and so allowed themselves a modicum of adornment. Not wishing to indulge in personal display did not mean those Protestants and Puritans that could afford it did not have tailors make their sober garments from rich if not ornate cloth and insist upon a fine cut and finish.

‘False Face Must Hide What the False Heart Doth Know’ – William Shakespeare

For more than a century women had been painting their faces in earnest and exposing themselves to the ravaging effects of lead make-up. Was it any wonder that ladies eventually turned to completely covering their faces? In 1615 a man called Edward Sharpham addressed this issue in his book The Fleire, with the principal character saying: ‘Faith, ladies, if you used but, on mornings when you rise, the divine smoak of this celestial herb Tobacco, it will more purifie, dense, and mundifie your complexion, by ten parts, than your dissolved mercurie, your juice of lemmons, your distilled snailes, your gourd waters, your oile of tartar, or a thousand such toyes.’

Perhaps not totally convinced of the healing power of smoke, full face-masks had already arrived in England from France via Italy, where in 1570 William Harrison stated masks were first devised and used by ‘curtizans’ (courtesans). That may have been so but eventually masks permeated into all levels of society, with ladies of all ranks adopting them, primarily as protection. Apart from covering pox marks and other blemishes, women were concerned about their complexions when riding or out in a carriage and did not relish garnering a glow from the sun. It does seem strange to us today but in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries it was desirable to appear pale and plump, a sign that your husband could afford for you to stay indoors and not engage in manual labour. Whereas during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries a tan has been suggestive of leisure time outdoors, previously it meant you were too poor not to work and so toiled in the fields.

Masks became an acceptable barrier to dust and grime, and gave women a way of moving about the city incognito when they were usually confined to the home, their every move judged on a moral level. Philip Stubbes in his The Anatomie of Abuses, written in 1583, tells us that:

When they use to ride a brod they have invisories, or visors made of velvet, wherwith they cover all their faces, having holse made in them against their eyes, whereout they look. So that if a man, that knew not their guise before, should chaunce to meet one of them, hee woould think hee met a monster or a devil, for face hee can see none, but two brode holes against her eyes with glasses in them.

There were several styles of mask, ranging from fluid fabrics such as velvet to stiff offerings consisting of an outside cover, a foundation and a lining. A reference in the Histoire des Jouets et Jeux D’enfants by Fournier mentions that from around 1540 a mixture of clay, paper and plaster called carton-pierre may have been worked together and pressed into moulds backed by coarse paper and steam dried. Literally translated carton-pierre means, ‘stone pasteboard ‘and had a papier mâché appearance, though was perhaps much heavier. Another possibility was buckram, a stiff fabric used in millinery, or pressed paper which resembled cardboard, both then being faced with fine fabric or silk and backed with ‘sweet skynnes’ or perfumed leather which would have been soft against the skin.

Stuart-era face masks, antique print.

Some masks were held to the face by means of a wand or stick but this meant both hands were not free. The other way was for the women to keep the mask in place by means of a small bead threaded on a length of twisted hemp attached to the lower part of the mask which she clenched in her teeth. An ingenious way of attachment one might say, though just how a lady was supposed to talk, let alone be charmingly witty, is possibly an art lost to time. It may have rendered an otherwise chatter-filled carriage ride in the company of a bevy of ladies amusingly silent for a thankful father or husband. But it was not only gentlewomen who adhered to this quirk of fashion, it was equally indulged by royalty. When walking in her garden Elizabeth I was recorded as having ‘put down her mask’ to speak to a visiting merchant from Holland.

Masks may have been introduced to England in the days of Gloriana and continued to protect the complexion in the decades preceding the Restoration, but it was only when Charles II retook the English throne and reinstated the theatre that a lady’s mask or ‘vizard’ (from the word visor) became an altogether different affair. Samuel Pepys is possibly our best source of evidence for this shift in the status of the lady’s mask, its ability to evoke an air of mystery, conceal and effectively render every woman, common and highborn, equal in their anonymity. Pepys himself found masks mildly frustrating, as recorded in his diary of 1661 when he allowed his clerk and his wife a ride into town with him in his carriage. He first thought the man’s wife to ‘be an old woman’ only to find out later, after she had removed her mask, that she was in fact ‘indeed pretty’. In 1663 he recounted that ‘ladies wear masks to the theatre which hides their whole face’, convenient for a lady if she wished to attend incognito. Such is illustrated by an entry in which Pepys tells us how his friend Lord Falconbridge was at the ‘Royall Theatre’ with Lady Mary Cromwell (third daughter of Oliver Cromwell), who ‘when the House began to fill she put on her vizard, and so kept it on all the play’. Unfortunately, by now the vizard was becoming a standard accessory of the prostitute who would look for custom both within the theatre and without, thus ladies in a full vizard ran the risk of appearing other than they were. Despite care being given to promote respect for the mask, Antoine de Courtin’s The Rules of Civility (1671) advises readers to ‘pay more civility’ to those wearing vizards ‘because many times under those disguises are persons of the highest dignity and honour’, it was too little too late. Pepys recounts an incident where he and some friends were in need of a carriage after an evening out and his wife being a little ahead of him was almost ‘taken up’ by a gentleman who did not recognise her as she was ‘wearing her vizard’.

Eventually, the word itself sank into depravity, vizard simply denoting a woman of easy virtue with theatres the places to meet them. Respectable women no longer frequented playhouses, which prompted individual premises to take action. When in 1703 the Daily Courant published a playbill for a performance of The Country House and ‘a consort of musick in Drury Lane’ it included a line which declared ‘and no persons to be admitted in masks’. This was wholly ineffective, compelling the government to intervene with an edict issued by Queen Anne that, among other things, ‘no woman be allowed or presume to wear a vizard mask in theatres’.

Beauty patches were first used to cover pox marks then were gradually adopted purely for adornment. (Author’s collection)

Masks did not however disappear altogether as the half-mask naturally took its place. Easier for a woman to hold a conversation as she no longer needed to hold it to her face by clenching her teeth around a bead, it was also easier for her to be recognised, though it was an unwritten rule that such revelations would not be disclosed. A half-measure of facial protection and anonymity was preferable to the full mask given the effect the latter had had upon women’s reputations. Did Sarah Fell of Swarthmoore Hall realise when she entered in her account book ‘1674 – October 17th – paid for a vizard maske for myself at 1s and 4d’ that twenty years later such a devilish object would be considered to have done more to ‘ruine more women’s virtues than all the bawds in towne’?

Face Patches – ‘Black Spots and Patches on the Face to Sober Women Bring Disgrace …’

If a woman was less inclined to embrace a half face mask it was perhaps no surprise that she naturally adopted the face patch to conceal her blemishes, smallpox scars or the ravages of potentially fatal make-up. Deadly cosmetics made it impossible for the skin to breathe and the damage inflicted was irrevocable, as one gentleman discovered to his cost on seeing his new wife the morning after the wedding. Writing as late as 1711, he recounts:

as for my dear, never man was so enamoured as I was of her fair forehead, neck, and arms, as well as the bright jet of her hair; but to my great astonishment, I find they were all the effect of art. Her skin is so tarnished with this practice, that when she first wakes in a morning, she scarce seems young enough to be the mother of her whom I carried to bed the night before. I shall take the liberty to part with her by the first opportunity, unless her father will make her portion suitable to her real, not her assumed countenance.

Opinions on the adoption of patching by the ladies of England also feature in John Bulwer’s book Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transform’d, or The Artificial Changeling, 1650. He complains:

Our ladies, have lately entertained a vain custom of spotting their faces, out of an affectation of a mole, to set off their beauty, such as Venus had; and it is well if one black patch serves to make their faces remarkable, for some fill their visages full of them, varied unto all manner of shapes and figures.

A ‘Warning to the Fair’, written in 1680, states:

But fair one know your glass is run,

Your time is short, your thread is spun,

Your spotted face, and rich attire

Is fuell for eternal fire.

In truth the threat of fire and brimstone did little to deter either Cavalier or Roundhead from patching during the first half of the seventeenth century, and so Parliament, always wishing to control what it saw as the excesses of the people, introduced a bill on 7 June 1650 to deal with the ‘vice of painting, wearing black patches and immodest dresses of women’. As usual, the legislation was aimed at what the government supposed was a predominantly female activity when in truth the wearing of patches was not just the prerogative of ladies.

The diarist Samuel Pepys, whose recording of everyday life in the mid-seventeenth century gives us an intimate insight into all things Stuart, mentions that his wife adopted the fashion of wearing patches of her own accord, apparently without seeking his permission. This seems strange to the modern woman who rarely, if ever, asks to be allowed to wear what she thinks suitable. Pepys, however, notes three months later that: ‘my wife seemed very pretty to-day, it being the first time I had given her leave to wear a black patch’. He adds a week or so later that his wife, with two or three patches, looked far handsomer than the Princess Henrietta. Ironically, he notes in his diary that on Monday, 26 September 1664 he too succumbed to the dubious fashion, after having been unwell. He wrote: ‘Up pretty well again, but my mouth very scabby, my cold being going away, so that I was forced to wear a great black patch.’

The Artificiall Changling, written in 1653 by John Bulwer. Bulwer’s aim, according to the full title, was to expose the ‘mad and cruel gallantry, foolish bravery, ridiculous beauty, filthy fineness, and loathsome loveliness of most nations, fashioning & altering their bodies from the mould intended by nature’. Bulwer describes in detail how people around the world artificially modify their appearance, noting that every nation has a ‘particular whimzey as touching corporall fashions of their own invention’.

Etiquette decreed, in the words of Charles II’s mistress Lady Castlemaine – whose word was law, that it was in bad taste to wear patches when in mourning but they were acceptable on the occasions of afternoons at the theatre, in the parks in the evening and in the drawing room at night. Yet, they were still ridiculed, with puritanical satirists unable to leave ‘patchers’ unmolested. In 1668 a poem called ‘The Burse of Reformation & Wit Restored’ informs us:

A seventeenth-century lady wearing a vizard or face mask. Antique print. (Author’s collection)

For pimples and for scarrs;

Heer’s all the wandring planett signes,

And some o’ th’ fixed starrs,

Already gumm’d, to make them stick,

They need no other sky,

Nor starrs, for Lilly for to vew,

To tell your fortunes by.

An interesting point here is that we are privileged to discover that in some cases patches are ‘ready gummed’, an unusual phenomenon if it was true as generally this is only associated with the modern world. As a rule, patches were made out of velvet, silk or taffeta and attached to the face by means of a crude glue which included glycerine. If you were a woman of limited means then patches made from mouse skin had to suffice. Patches were both home-made and shop bought, purchased alongside other lady’s accoutrements such as fans and hair ornaments. Their manufacture provided a sustainable piecework industry for children and older women confined to the home. So numerous were the number of patches made that they became known as ‘mouchete’, or ‘small flies’, and in Venice there is still a street called Calle de le Moschete where these fake beauty spots were produced. Joseph Addison, who co-founded the Spectator with his partner Richard Steele, wrote an account on the trend of ‘patching’ after visiting an opera in Haymarket. With the seventeenth century only just having given way to the first years of the ever political eighteenth, his observations make delightful reading. He did, however, warn in the Spectator on Saturday, 2 June 1711 that:

This account of Party Patches will, I’m afraid appear improbable to those who live at a distance from the fashionable world.

Patches had secret meanings depending where they were placed on the face. (Author’s collection)

About the Middle of last Winter I went to see an Opera at the Theatre in the Hay-Market, where I could not but take notice of two Parties of very fine Women, that had placed themselves in the opposite Side-Boxes, and seemed drawn up in a kind of Battle-Array one against another. After a short Survey of them, I found they were Patch’d differently; the Faces on one Hand, being spotted on the right Side of the Forehead, and those upon the other on the Left. I quickly perceived that they cast hostile Glances upon one another and that their Patches were placed in those different Situations, as Party-Signals to distinguish Friends from Foes. In the Middle-Boxes, between these two opposite bodies, were several Ladies who Patched indifferently on both Sides of their Faces, and seem’d to sit there with no other Intention but to see the Opera. Upon Inquiry I found, that the Body of Amazons on my Right Hand, were Whigs, and those on my Left, Tories: And that those who had placed themselves in the Middle Boxes were a Neutral Party, whose Faces had not yet declared themselves. These last, however, as I afterwards found, diminished daily, and took their Party with one Side or the other; insomuch that I observed in several of them, the Patches, which were before dispersed equally, are now all gone over to the Whig or Tory Side of the Face. The Censorious say, That the Men, whose hearts are aimed at, are very often the Occasions that one Part of the Face is thus dishonoured, and lies under a kind of Disgrace, while the other is so much Set off and Adorned by the Owner; and that the Patches turn to the Right or to the Left, according to the Principles of the Man who is most in Favour. But whatever may be the Motives of a few fantastical Coquets, who do not Patch for the Publick Good so much as for their own private Advantage, it is certain, that there are several Women of Honour who patch out of Principle, and with an Eye to the Interest of their Country. Nay, I am informed that some of them adhere so stedfastly to their Party, and are so far from sacrificing their Zeal for the Publick to their Passion for any particular Person, that in a late Draught of Marriage-Articles a Lady has stipulated with her Husband, That, whatever his Opinions are, she shall be at liberty to Patch on which Side she pleases.

I must here take notice, that Rosalinda, a famous Whig Partizan, has most unfortunately a very beautiful Mole on the Tory Part of her Forehead; which being very conspicuous, has occasioned many Mistakes, and given an Handle to her Enemies to misrepresent her Face, as tho’ it had Revolted from the Whig Interest. But, whatever this natural Patch may seem to intimate, it is well known that her Notions of Government are still the same. This unlucky Mole, however, has mis-led several Coxcombs; and like the hanging out of false Colours, made some of them converse with Rosalinda in what they thought the Spirit of her Party, when on a sudden she has given them an unexpected Fire, that has sunk them all at once. If Rosalinda is unfortunate in her Mole, Nigranilla is as unhappy in a Pimple, which forces her, against her Inclinations, to Patch on the Whig Side.

I am told that many virtuous Matrons, who formerly have been taught to believe that this artificial Spotting of the Face was unlawful, are now reconciled by a Zeal for their Cause, to what they could not be prompted by a Concern for their Beauty. This way of declaring War upon one another, puts me in mind of what is reported of the Tigress, that several Spots rise in her Skin when she is angry, or as Mr. Cowley has imitated the Verses that stand as the Motto on this Paper, ‘… She swells with angry Pride, And calls forth all her spots on ev’ry side.

As well as declaring political loyalty, a more discreet code also developed as a means of communication between lovers. Books were written on the art of patching, full of instructions as to where to position a patch to convey a precise message. While a patch near the eye indicated passion, one by the mouth showed boldness. A married woman could wear a spot on her right cheek whereas if she were only engaged it would have to be placed on the left.

A beauty spot on the corner of the eye indicated passion, while one near the eyes suggested irresistibility. Other beauty spot meanings included: on the throat – gallantry; on the nose – boldness or shamelessness; in the middle of the forehead – dignified; and the middle of the cheek – bold; touching the edge of lower lip – discreet; near the corner of the eye – available; and one beside the mouth – a tantalising ‘I will kiss but go no further’.

The need for patches led to an equally lucrative trade in patch boxes, which were cheap and convenient presents for young girls and women to give to each other. Equally, a small box inscribed with a secret message could be given as a clandestine gift between lovers

Patches continued well into the Georgian era, only really going out of fashion in the Regency period, but there was always concern about a woman’s obsession with the ‘patch’. A wonderful piece in the Ipswich Journal, dated 1774, illustrates this concern, which had been present from the inception of the fad. A certain gentleman named Sir Kenelm Digby was in no way enamoured of women’s beauty patches, thinking them quite unnecessary; vulgar in fact, stating that should they have occurred naturally on a woman’s face they would be deemed a deformity. He could not understand why a woman with an unblemished countenance should wish to deform herself so? To illustrate his dislike he recounted a tale of a relation of his, a niece who being a stunning natural beauty paid him a visit one day her face sporting several patches on her otherwise flawless countenance. Sir Kenelm argued with her hoping to dissuade her from the use of such ornaments citing the fact that as she was pregnant at the time no good could come of it. ‘Have you no apprehension that your child may be born with half-moons upon his face; or rather, that all the black which you spot in several places, up and down, may assemble in one, and appear in the middle of his forehead?’ This did in fact prompt her to stop using patches, his words having such a influence on her imagination that when she was delivered of a daughter who was born with a spot ‘as large as a crown of gold in the middle of her forehead’ she blamed herself for the unfortunate deformity unreservedly.

The Fan – Provider of Privacy, Mystery and Allure

Just as there was a potential secret language inherent in where a face patch was placed, so too the fan was an instrument both of practicality and intrigue. Itself an object of mystery constructed from ‘leaves’, ‘rivets,’ ‘ribs’, ‘sticks’, ‘slips’ and ‘guardsticks’, this moveable work of art was undoubtedly a most important accessory for a wealthy woman in the seventeenth century. Huge quantities of fans were imported into Europe from China by the East India Company from the seventeenth century onwards. For years fixed or paddle fans had been the norm, mostly consisting of feathers set into ornate handles. Indeed, Queen Elizabeth I of England declared that ‘the only worthy gift of a queen are fans’, though this could well have originated from the queen having been told that she had very beautiful hands, and holding a fan would emphasise such beauty. But later it was the folding fan which became a status symbol, the rich able to afford exquisite examples of silk stretched between handles of ivory, carved wood or even gold studded with jewels. The French especially loved the fan and one belonging to Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV, included paper that was cut in imitation of lace, contained ten painted miniatures, took nine years to make and cost almost £20,000. Artists that decorated fans were not averse to signing them as they would a painting, as some were indeed works of art.

As the fan eventually filtered down to women at all levels of society it was clear its popularity lay not so much in its stunning craftsmanship as in its ability, when correctly handled, to speak volumes in a world which generally allowed women few words.

Just as newspaper proprietor Joseph Addison had lampooned patches in his Spectator, he also wrote a satirical piece on women’s adoration of the fan. He decries that ‘Women are armed with fans as men with swords, and sometimes do more execution with them.’ He alludes to the many ways a fan can be unfurled, slowly and deliberately with many different flicks of the wrist, each denoting a myriad of different emotions. Similarly, the means by which a fan was closed, sometimes with ‘a crack like a pocket-pistol’, could show just what humour a woman was in. He finishes with describing the infinite ways a fan can be fluttered:

There is an infinite variety of motions to be made use of in the flutter of a fan. There is the angry flutter, the modest flutter, the timorous flutter, the confused flutter, the merry flutter, and the amorous flutter. Not to be tedious, there is scarce any emotion in the mind which does not produce a suitable agitation in the fan; insomuch, that if I only see the fan of a disciplined lady, I know very well if she laughs, frowns, or blushes. I have seen a fan so very angry, that it would have been dangerous for the absent lover who provoked it to have come within wind of it; and at other times so very languishing, that I have been glad for the lady’s sake the lover was at a sufficient distance from it. I need not add, that a fan is either a prude or a coquette, according to the nature of the person that bears it.

‘Women are armed with fans as men with swords, and sometimes do more execution with them’, Spectator, 1711.

Lady with the Veil, Alexander Roslin, 1768.

The observation that ‘ladies have but little talk and the main conversation is the flutter of the fans’ was both true and naïve. In fact, ladies well versed in the art of the fan were speaking a most clandestine language which could see a lady communicate across a room without saying a word. Unfortunately, men wishing to enter into a relationship with any female of the time would also have to observe the rules closely. There were more than a dozen basic fan-related gestures that a man would need to know, for example:

Touching left cheek – no

Twirling in right hand – I love another

Fanning slowly – I am married

Fanning quickly – I am engaged

Open and shut – you are cruel

Open wide – wait for me

Presented shut – do you love me?

With handle to lip – Kiss me

In right hand in front of face – Follow me

Drawing across the cheek – I love you

Placing on left ear – I wish to get rid of you

For an interested beau it must have been a minefield as variations on the themes also applied. If a lady appeared upon her balcony, slowly fanning herself, before returning inside and closing the windows after her it meant ‘I cannot go out’. If she did the same but fanned herself excitedly and left the windows open, it meant that she’d be out soon. Slow fanning on its own meant ‘Don’t waste your time I do not care for you’, while fanning at speed denoted ‘I love you so much’. Carrying the fan closed and hanging from her left hand meant the lady was engaged, but if hanging from her right meant the opposite and she was wishing she was so. If she dropped her fan the gentleman may deduce that she ‘belongs to him’, while a half-open fan over a woman’s face warned of being watched.