Gorgeous Georgians

‘False rumps – false teeth – false hair – false faces –

Alas! Poor man how hard thy case is;

Instead of ‘woman, heav’nly woman’s charms,

To clasp cork – gum – wool – varnish – in thy arms.’

Epigram entitled ‘Man’s Misfortune’, Hampshire Chronicle, 1777

T here was no ignoring aristocratic ladies’ ‘high-hair’ during the Georgian era. Women fainted from the weight of additional wigs and decorations, ducked under doors to avoid collisions and sat on the floors of coaches due to the scale of it. Many employed 2lb of whitening powder per ‘dressing’ simply to maintain their extravagant styles.

The epitome of an ‘age of elegance’, an elaborate hairstyle was of course just another dazzling and impractical creation, along with wide skirts and beauty patches, which became de rigueur for members of aristocratic society.

There were no end of contraptions and contrivances on the market aimed at contorting the symmetry of the human form into a parody of itself. The eighteenth century was an age where nothing was as it seemed and gentleman protested that they preferred their women to be, if nothing else, at least real. Upper class men were concerned that beneath a woman’s powder and wigs they didn’t really know what their wives and sweethearts looked like or whether they would recognise them without it? A poem in the Lady’s Magazine of 1777 seems to hit the nail right on the head:

A 1776 print entitled OH-HEIGH-OH showing an elaborate hairstyle full of twists and curls. If not a wig then false hair would have been used to create such a gravity defying style with sugar water employed to add volume. (Library of Congress)

Give Chloe a bushel of horsehair and wool

Of paste and pomatum a pound

Ten yards of gay ribbon to deck her sweet scull

And gauze to encompass it round.

Let her gown be tucked up to the hip on each side

Shoes too high for to walk or to jump

And to deck the sweet charmer complete for a bride

Let the cork cutter make her a rump

Thus finished in taste while on Chloe you gaze

you may take the dear charmer for life

but never undress her, for out of her stays

You’ll find you have lost half your wife.

Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire (1757–1806). (Author’s collection)

A Pig in a Poke by James Phillips, 1786. This before and after cartoon illustrates how by donning a false rump, wig and petticoats the Georgian woman’s figure was exaggerated. (Library of Congress)

The Georgian woman in all her incarnations was a creature of pretence. That is not to say that gentlemen did not also indulge in padding and disguise, but it was in female dress that we see the greatest deceptions. By deconstructing the frivolous sentiments of the poem quoted on p. 55 it is possible to unravel the layers that made up the Georgian beauty.

Hair: Pigtails, Pomatum and Periwigs

It was never the aim of the upper class Georgians to look natural. To be ‘styled,’ was paramount and this extended not only to dress but to taste and manners. Dressed hair was ‘polite hair’ in civilised Georgian society. Hair was elaborate and necessitated extensions – ‘top pieces’ for crowns, ‘borders’ for the front, ‘curls, neck braids and chignons’ of various lengths for the back. If that wasn’t enough, feathers, jewels and fabrics were often added. A satirical entry in the Gentleman’s Magazine of 1773 commented: ‘such bushes of hair as the ladies bore upon their heads in the last and present year so enormous that they seem to require a gardener’s sheers instead of scissors, to reduce them to tolerable dimensions!’ Satire aside, there was a thriving market for human hair and hair merchants sourced the best quality both from England and abroad. As hairdresser James Stewart observed in 1782, hair ‘was a considerable article in commerce’ and sold that year for between 5 shillings and £5 per ounce (dependent on quality). The most sought after hair was that from a healthy virgin. Hair supplies from abroad were quarantined for fear of it bringing plague or other terrible diseases into the country, and if there was a shortage then at the other end of the financial scale cheap wigs were available, made of horsehair and wool which made them extremely uncomfortable.

Eventually gendered and popular with both sexes, wigs were originally used to cover thinning or general hair loss, with high-profile women such as Queen Elizabeth I and Mary Queen of Scots owning a collection of different styles. However, the majority of wigs were first worn by men.

The word ‘wig’ came into the English vocabulary by a strange evolution. Starting in Rome, the word pilus travelled to Spain where it became pelo and peluca. In France the word changed to perruque and in Holland to peruic. Coming to England from the Low Countries, it became ‘perwick’, ‘perwig’, ‘periwig’ and finally was shortened to ‘wig’.

During the English Civil War (1642–51) there was no time for wigs. Hair tended to be a man’s own but on the Restoration of the monarchy there was a wig upon every fashionable Englishman’s head, King Charles II himself having adopted the full-bottomed wig, a style that exaggerated his ‘majesty’ and commanded respect. By its very construction of row upon row of curls reaching to the chest, it proved to be extremely expensive, costing between 30 and 40 guineas, and fading from fashion by the 1720s. The tradition was continued by the legal profession, ecclesiastical dignitaries and of course doctors, of whom the public, according to Fielding’s farce, The Mock Doctor, ‘would put the least confidence in a physician who wore his own hair’.

Other types of wigs, however, were more affordable, but seen as no less important. In his treatise on hairdressing entitled Plocarosmos, or The Whole Art of Hairdressing (1782), James Stewart concluded, ‘all conditions of men were distinguished by the cut of his wig’. Thus, there was a wig to suit any office in life.

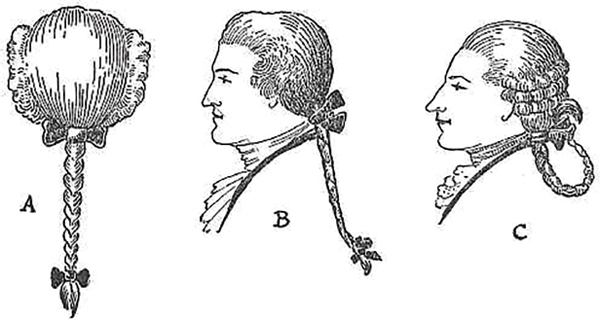

Tie wigs caught the hair at the back of the neck and held it with a bow, and were the most popular type and formed the basis of many other styles. Pigtail wigs, for example, consisted of either one, two or three lengths of hair tightly wrapped in a spiral manner with black silk ribbons. They were tied at the nape of the neck with a ribbon bow. It was a fashion particularly popular during the reign of George II and very expensive. The Mildmay Papers held at the Essex Record Office suggest that in 1734 the price of ‘a tied wig’ was over £7.

A barber and wigmaker’s shop from Diderot’s Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, c. 1751. (Author’s collection)

Good quality wigs were targets for thieves with wigs even being whipped off men’s heads in broad daylight. Entries in the Newgate Calendar bear witness to just how serious an offence this was perceived to be. On 8 March 1698 Edward Short of St Martin-in the-Fields was indicted for robbing Peter Newell of a hat and ‘periwig’. Charged with violent highway robbery, the accused received the death penalty. John Corbet of the parish of St Faith’s, London was likewise condemned for ‘violently taking from James Shippard, upon the Queens Highway, a peruke’. George Hayns of St Giles-in-the-Fields was convicted of stealing a ‘periwig from Jacob Coler in Drury Lane’ in 1717. All were executed.

The ‘bag’ wig was not only fashionable but convenient. A square or rectangular bag was drawn tight about the end of the hair with a bow and a drawstring and protected the coat from grease and powder. However, by the 1740s the bag was often so large that it practically covered the shoulders of the wearer. A useful sideline from this particular fashion was that impoverished men and women could earn a meagre living from making such bags.

The Ramillies was essentially a military wig, thought to take its name from the battle of that name that was fought between the French and the English in 1706, during which in order to free themselves from their cumbersome full-bottomed wigs soldiers plaited the hair into long queues called ‘Ramillie-tails’. These were tied and fastened with a large bow at the nape of the neck, and a smaller one at the end. It was a style favoured by younger men and it was thought to imbue them with a military air as the wig became standard dress for the British Army. Read’s Weekly Journal of 1 May 1736, in a report on the marriage of the Prince of Wales, stated that ‘the officers of the Horse and Foot Guards wore Ramillie periwigs by His Majesty’s order’.

Sir Richard Haddock (1629–1714), Admiral of the Royal Navy, wearing a ‘full-bottomed’ style of wig. (Author’s collection)

The rise and fall of the male periwig was phenomenal with styles including the ‘Campaign’ or ‘Travelling’ wig, the ‘Bob’, both ‘long’, ‘short’ and ‘snug’, the Caxton, Toupee and Foretop, the Spencer, the Adonis, the ‘Natty Scratch’, a sports, riding and business wig, as well as those that were ‘frizzed’ and ‘grizzled’ and the plain ‘Cut Wig’, mainly worn by artisans. Wigs found favour with parsons and in the course of time they became indispensable, even warranting recommendation. In 1756 a volume was issued under the title of Free Advice to a Young Clergyman, written by the Revd John Chubbe, in which he advised the young preacher always to wear a full wig until age had made his own hair respectable. Wigs even made it on to the second-hand market, re-shaped and re-dressed to the best of a hairdresser’s ability.

But nothing was to prove as popular as the ‘high hair’ adopted by ladies when, in 1770, wigs became fashionable among women too. Taller, more sophisticated and not to mention preposterous, they were to overtake the trend that had seen men both shave their heads and disguise their natural hair.

As the demand for male wigs had been waning, in the 1760s suppliers found their livelihoods in jeopardy. Out of necessity, in 1765 wigmakers petitioned King George III to grant them relief ‘in consideration of their distressed condition occasioned by so many people wearing their own hair’. The answer was for wigmakers, who had gradually evolved from simple barbers, to now re-emerge as hairdressers, catering for the puffs, rolls, pigtails and bags which continued to be used in much the same manner as before. If you were, however, practised in the art of applying powder and pomatum, you would always be indispensable to both sexes.

A bag wig.

Ramillies wig.

No more than animal fat, pomatum needed to be perfumed to achieve a sweet smell, and in order to have a clear cream appearance and light texture the grease ideally had to be taken from a young and healthy animal. Powder, on the other hand, a product that had been in use from the early 1700s, was obtained from many sources and was easily corrupted. Standards did apply but as a gentleman’s wig or hair required only black, white, brown or grey colouring they were easier to adhere to. At the other end of the scale, ladies had a penchant for pastel colours, namely pink, light violet or blue and so pigments added could mask a bad product.

Des Victoire Coiffure a la Grenade, 1779. (Library of Congress)

Whereas the best hair powders consisted of starch from corn, wheat, rice and occasionally potato, cheaper powders were made up of flour, alabaster, plaster of Paris, whiting and lime. Despite the law decreeing hair powder had to contain starch, many ignored it. According to the Newcastle Courant, dated 1739, ‘On Tuesday about 20 peruke-makers were convicted at the Excise-Office for using and having in their custody Hair-Powder not made of starch.’ On 20 October 1745, it was recorded that fifty-one barbers in England were convicted before the commissioners of excise, and fined a penalty of £20, contrary to an Act of Parliament, as were forty-nine others in the same month.

As ladies’ hair creations grew so did the demand for the powder that coated the sculpting pomatum and fixed the style. Powder was applied in a small room designed for the purpose (and the upwardly mobile) with the client cloaked in a powdering garment, sitting in a chair. As he/she then protected the face and eyes with a paper mask or funnel-shaped ‘nosebag’, the barber, using a bellows or large powder-puff, enveloped his client’s head in powder. It was said that you could judge a lady’s intellect, if not her common sense, by the powder in her wig. No less extraordinary was a young man seen leaving a barber’s shop, ‘his wig containing a pound of hair but with two pounds of powder in it’, as recorded in a contemporary newspaper. The importance of a well-powdered head was reiterated by a young man who wrote in a periodical paper in 1751, ‘my mother would rather follow me to my grave than see me sneak about with dirty shoes and blotted fingers, hair unpowdered, and a hat uncocked …’.

Wigs were convenient to maintain as one could send them back to the barbers for re-dressing at regular intervals. The alternative was having to sit while your hair was combed, pulled, frizzed, teased, rearranged about pads of greasy wool and pinned, pomaded, pummelled and powdered into shape. Yet the dressing of the hair was only half of the process. The other half was just ‘wearing’ your new hairstyle, day and night, for an average of three or four weeks, and in some cases even sleeping sitting up to preserve it. Only after time would the creation be pulled down and rebuilt. Even if a lady could have afforded the expense of a daily change in order to prevent the animal grease in the pomatum becoming rancid and attracting bugs or at worst nests of mice, it is unlikely she would have wanted to spend hours in the hairdresser’s chair.

A wonderful extract from the London Magazine of 1768 gives us a first-hand account of such activities:

I went the other morning to make a visit to an elderly aunt of mine,

when I found her pulling off her cap and tendering her head to the

ingenious Mr. Gilchrist, who had lately obliged the public with a

most excellent essay on hair. He asked her how long it was since

her head had been opened or repaired. She answered, ‘Not above

nine weeks.’ To which he replied it was as long as a head could

well go in the summer, and that therefore it was proper to deliver

it now: for he confessed that it began to be un peu hazardie.

The discomfort ladies must have felt from their elaborate hairstyles was addressed by the introduction of head-scratchers, which, used in open company, were made from either bone, ivory, silver or gold depending on means.

Aside from physical discomfort, sporting high hair was fraught with other problems. Poet Samuel Rogers (1763–1855) recollected in his youth that ladies’ dressed hair ‘was of a truly preposterous size’. On one occasion he was obliged to share a coach with a lady who had to sit on a stool placed at the bottom of the coach as the height of her headdress did not allow her to sit on the seat! How battered and bruised she must have felt once she had spilled out of the coach is anyone’s guess. Dancing was no easier as ladies with high hair could not pass under the raised arms of their gentleman partners. It is also rumoured that a side door in St Paul’s cathedral had to be raised at least 4ft just to enable women to enter the building.

It wasn’t always the hair that confounded matters, as hair ornaments also posed a danger to the wearer. When the Duchess of Devonshire introduced feathers a yard high into her coiffeur there was public outcry. She was branded ‘immoral’ and ladies who did likewise were denounced from the pulpit, insulted, mobbed and persecuted. Candle-lit chandeliers were also a hazard as hair could catch fire when a lady passed under it unaware of the danger until it was too late.

In the last decade of the eighteenth century the whole phenomenon of enormous wigs and powdered hair was becoming a contentious subject. On 16 January 1790 one gentleman writing in the Norfolk Chronicle considered, as wheat was in short supply and the country engaged in corn and bread riots, whether it was wise to use the precious commodity for the hair instead of putting it into the mouths of the hungry? To the best of his ability he attempted to calculate just how much flour was used for the ‘unnecessary’ upkeep of the nation’s heads. He assumed that out of 40,000 inhabitants there were on average 5 to a family, resulting in 8,000 families, a number he then halved because due to their ‘situation in life’ they could not be ‘supposed to use powder’. He then absolved a further 2,000 families for being only occasional users and so consequently having a ‘trifling effect’ on the equation, settling on the remaining 2,000. Of these he reckoned 3 individuals in every 2 families were in ‘constant use of it’, having their hair or wigs dressed daily with powder.

A gentleman ‘with a queue’ in four dressings consumes 1lb. of powder – the ladies much more; it will therefore be making a full allowance for those who dress more lightly to calculate the consumption of each individual at half a pound weekly or 1,500 lb. altogether. As much wheat is consumed in the manufacture of 1lb of flour, there being as much waste attending the process of making starch, which is powder unground, as of grinding of wheat into flour. One lb. of flour will make 1lb 5oz of bread and as 6 lb. of bread will supply an individual for a week, 5lb of flour will be more than sufficient; 1,500lb which is used in hair powder will then be found adequate to the support of 300 persons – a fact so striking it needs no comment.

The Flower Garden, hand-coloured etched engraving published by M. Darly in 1777. (Library of Congress)

The writer states that he has not in any way exaggerated his findings and calls on his fellow citizens to ‘refuse to still the cries of only one poor infant, to indulge in the paltry gratification of a powdered head’.

Powder was still used up until 1793 when ladies finally abandoned it taking their lead from Queen Charlotte, wife of George III. The French Revolution also effected a change as in France a powdered head or wig was a sign of aristocracy and a sure route to the guillotine. In England on 5 May 1795 a tax on hair powder was introduced in an attempt to end the practice. The Duty on Hair Powder Act was passed by Parliament and not repealed until 1869.

To the modern eye the tax appears amusing. Everyone wishing to use hair powder had to visit a stamp office to enter their name and pay for an annual certificate costing 1 guinea. As with any dictate, there were certain exemptions, the most obvious being the royal family and their servants, as well as clergymen with an income of under £100 a year, but the tax did eventually have the desired effect.

‘Lucy Locket Lost her Pocket …’

From the seventeenth to the late nineteenth centuries most women had at least one pair of pockets, which served a similar purpose to the handbag today. Unlike a handbag, however, pockets were rarely if ever seen as they were usually worn underneath the skirt, usually tied around the waist under a lady’s petticoats. To access her pockets a woman simply had to slip her hands into slits in the side seams of her gown and into the opening of the pocket. Men didn’t wear separate pockets, as theirs were sewn into the linings of their coats, waistcoats and breeches.

Many pockets were handmade and they were often given as gifts. Some were made to match a petticoat or waistcoat, while some were made over from old clothes or textiles. Pockets could also be bought ready-made from a haberdasher.

Women kept a wide variety of objects in their pockets. In the days when people often shared bedrooms and household furniture, a pocket was sometimes the only private, safe place for small personal possessions.

‘Lucy Locket Lost Her Pocket’ is a well-known nursery rhyme, though totally unsuitable for the nursery. Its adult message is one of taking care with what you wish for – rival mistresses Kitty Fisher and Lucy Locket and references to Cassanova and Charles II – while also illustrating that from the lowliest of women to ladies and queens pockets were an indispensable part of a woman’s life. However, being detachable, like Tudor sleeves two centuries before, they could be lost or even worse stolen. The Old Bailey records tell us that thieves known as ‘pickpockets’ used a variety of methods to snatch pockets such as cutting the pocket strings and grabbing the pocket or slashing the pocket itself so the contents fell out.

‘On 5 November 1716 Robert Draw of London, labourer, was indicted for privately stealing from Martha Peacock a linen Pocket (value 2 shillings) complete with contents’, as recorded in Proceedings of the Old Bailey. Martha told the authorities that she had been going along the street when the prisoner had come up behind her, thrust his hand up her riding-hood and pulled her pocket off. She said she had cried out causing a chase to take place. Eventually knocked down, the accused was found to have the pocket upon him. Though found guilty to the value of 10 pence, he vehemently denied the charge. William Carlisle was also brought before the Old Bailey Courthouse, where on 4 December 1717 he was duly charged with privately stealing a ‘Pocket, value 1 pence; 2 Gold Rings, value 19 shillings, … a Laced Handkerchief, value 10 shillings and 2 shillings 6 pence in Money, from the Person of Susan Wright’. The assault had been an embarrassing one as Carlisle ‘with great violence’ had pulled off the pocket inadvertently, tearing down her petticoat in the process of doing so. The woman in a state of undress was not able to give chase, though she believed the boy who had eventually been apprehended was the culprit. Lack of evidence resulted in the lad being acquitted.

Pickpockets answered to a variety of names, as one poor woman standing in St Bartholomew’s fair with a child in her arms discovered in 1729. A ‘sharper’ cut a hole in her pocket so dextrously that he got away with 20 shillings and a gold ring of the same value. Covent Garden Playhouses were another lucrative venue for the pickpocket where booty was pawned almost as fast as it was stolen with Grays Inn Lane becoming the place one lady was knocked down by two fellows who proceeded to cut off her pockets and rob her of her satin cloak, ‘a muff and bonnet’. If transportation was not a thief’s fate then the gallows certainly were, as Sarah Kingman found out after she had picked the pocket of Moses Wheeler in 1739.

Pockets were completely separate from any garment and reached via discreet openings in the side of a woman’s skirts and petticoats. (Photograph Tessa Hallmann)

In order to secure one’s pockets during the night it was common practice to put them under your pillow, but it was no cast-iron solution. Even empty pockets were valuable and stolen along with other garments as all items of clothing were liable to theft as they could easily be pawned. Advertisements for stolen goods often appeared in newspapers. After having two pairs of pockets stolen in January 1772 along with tablecloths, shifts, stockings, aprons, gloves, a dresser cloth and a silver spoon, a gentleman in Fulham, London posted in the Public Advertiser that if anyone witnessed the items being offered up to be pawned or sold, they should stop them and ‘give notice to Sir John Fielding whereby you shall receive five guineas reward on conviction of the offenders’.

Before James Dalton, the notorious ‘captain’ of a street robbery gang operating in the Smithfield area of London, was finally hanged at Tyburn in 1730, he reputedly revealed the safest way for a lady to wear her pockets, given that from childhood he had become an expert in removing them. Explaining that pickpockets could easily ‘whip hold of’ a pocket when worn under hoop petticoats, he went on to advise that they should instead tie them between their hoops and upper petticoats so that they might defy all the thieves in London.

In the closing decade of the eighteenth century fashions changed dramatically and the wide hoops and full petticoats that could hide a pocket went out of style. New high waistlines and a slender silhouette prompted a change in the way a woman secured her personal belongings. It was now that the forerunner of the handbag took shape. Called a reticule, it was designed to be worn on the arm and would soon become an indispensable female accessory. For many it could not replace the roomy secret of the pocket and in some cases, among the less fashionable, pockets continued to be worn. In 1819 Theresa Tidy wrote a small guide for young women entitled Eighteen Maxims of Neatness and Order in which she points out the manners best acquired by a gentlewoman. It is evident that even two decades after their apparent demise she still advocates the use of the pocket as she advises most strongly, ‘Never sally forth from your own room in the morning without that old-fashioned article of dress – a pocket. Discard forever that modern invention called a ridicule (properly reticule).’

A pickpocket/cutpurse at work, from the Lottery Contrast, 1760, by an unknown artist. (Library of Congress)

It is a well-known adage that what goes up must eventually come down, and an ‘Essay on Fashion’ featured in Town and Country magazine of 1787 reiterated such in no uncertain terms. Looking back over recent years, the article informed its readers that the towering and pompous ladies headdresses of the last few seasons alone could have filled an entire volume. It then pointed out that recently ‘what women had taken from their heads, they have added to their hips’, closing finally with relief that now the enormous hoops and large high hair had at last ‘sunk under their own weight’ the way was left clear for ‘false rumps to be in vogue’.

It is doubtful that the modern woman – to whom comfortable clothes and ease of movement are paramount, could appreciate just how radical a change these new ‘false’ or ‘cork’ rumps were for her ancestor. Our distant grandmothers were about to be released from the tyranny of the infernal ‘hoop’, which like the farthingale before and the crinoline after would ensure a woman would not go unnoticed, ‘so much are they persuaded that their merit be in proportion to the space they occupy in the world’ as a contemporary newspaper reported.

It is hard to imagine what it must have been like to be dominated by a hoop whether full, half or basket-like, not to mention the names that had to be remembered. Such was the tyranny of the ‘cage’ that old French hoops had identities, for example, the ‘Gourgandine’, or the flirting hoop, the ‘Tatez-y’, or ‘groping hoop’, or the ‘Ceillrite’, otherwise known as the ‘flying top-over- tail hoop’. Perhaps the latter was partly to blame for the incident reported in the Derby Mercury on Friday, 7 December 1748:

Last night the ball at St James was very brilliant, their royal hignesses the prince and princess of Wales opened it, and afterwards Prince George and Princess Augusta danced. An accident happened at the ball which put two ladies into a great confusion; one of them going to take her seat by the other, in taking up the side of her hoop happened, by accident to fling it over her head, which caught hold of a sprig of diamonds and could not be disentangled for some time which however ended with no other bad consequences than much disordering the ladies head and occasioning some mirth to the noble audience.

Perhaps the most recognisable eighteenth-century underskirt construction was the pannier, which took its name from the French for ‘basket’. This could either be a huge full-petticoat contraption which set its wearer out into the world like a galleon in full sail, or shorter ‘side-panniers’ which sat over each hip and were marginally more comfortable but had a woman resemble a pack horse. Often these small baskets were able to collapse up on themselves and so render a woman more manoeuvrable. Whichever was preferred, both dominated the middle part of the eighteenth century and are instantly recognisable as the undergarment that gave a woman her unique ‘oblong’ silhouette. Flat to the front and back, this wide shape was a favourite at court, in fact ordered to be worn by Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, as it was the best way to exhibit exquisite gowns. The width of panniers was varied. Some were modest while others could extend out from the waist up to 4ft on either side.

The absurdity of this fashion attracted biting social comment and many caricaturists poked fun at the women who wore them. In 1741 a contributor to the London Magazine noted, ‘I have been in a moderate large Room, where there have been but two Ladies, who had not enough space to move without lifting up their Petticoats higher than their Grandmother’s would have thought decent.’ Not only were these skirts absurd but also nowhere near lightweight. Materials used included cane, wood, whalebone or reeds and were at best inconvenient as if a lady did not choose to rest her arms upon her skirts, she would experience back ache. In addition, one had to learn how to wear them. No lady could simply don a hoop and know how to manoeuvre herself either indoors or out.

A complete Georgian gown. (Photograph Tessa Hallmann)

Georgian side-panniers. (Photograph Tessa Hallmann)

Doorways were a particular hazard. As some panniers were designed to collapse up upon themselves it was possible for a lady to pull her skirt up and in at the sides thus reducing her width. If this was not possible she simply had to negotiate a doorway by going through it sideways. Chairs could only be sat on if they were without armrests, while carriages had to be entered carefully, often with a footman pushing from behind. Such was mentioned in the London Magazine of 1741, where it applauded how a lady might get ‘in and out of the narrow limits of a chair or chariot ever so skilfully or modestly, yet she makes a very odd grotesque figure with her petticoats standing up halfway up the glasses [windows] and her head peeping out above them’. Women often became entangled in other women’s skirts and if taking a gentleman’s arm the man in question would have to walk slightly in front of his female companion to accommodate the amount of space she occupied. Dancing was by no means an intimate affair as all movement was obliged to be undertaken at arm’s length.

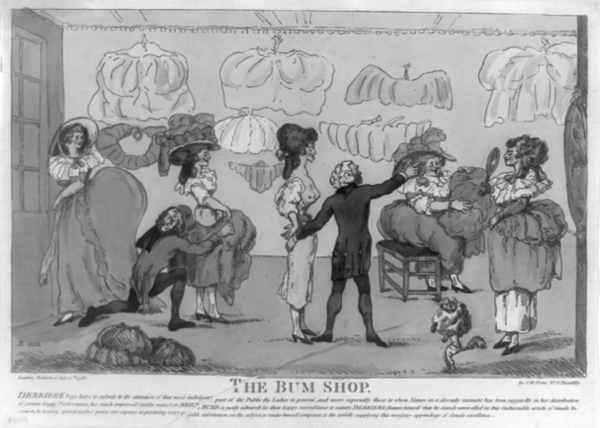

Fortunately, salvation was on the way in the guise of the false or cork rump, releasing women from twenty years of being ‘oblong’ to once more becoming rounder. It was in effect a ‘bustle’ before the Victorians had invented the concept and were pads filled with fabric or cork, tied at the waist and draped over the derrière, ‘poofing’ out the skirt at the back. As with all things the fashion lead to a flood of satire and derision. ‘Bum-shops’ sprang up all over London, encouraging ladies of all incomes to ‘get your false bums here’. It only added to gentlemen’s confusion as to what real women looked like.

An antique print of 1875 depicting dress in the eighteenth century named Modes des Femmes. (Author’s collection)

Cork rumps were popular enough to see bewildered husbands and fiancés write to newspapers and broadsheets for help, such as the 1776 December issue of the Weekly Miscellany:

A most ingenious author has made it a question, whether a man marrying a woman may not lawfully sue for divorce on the grounds that she is not the same person? What with the enormous false head-dress – painting – and this new-fangled cork substitute – it would be almost impossible for a man to know his bride the morning of his nuptials. If the ladies look on this invention as an ornament to their symmetry, I will engage they shall be excelled by almost any Dutch market-woman or fat landlady in this kingdom.

A cartoon by Matthew Darly from 1777 entitled ‘Chloe’s Cushion or The Cork Rump’ epitomises the fervour for the appendage though wearing it could be hazardous. During a riot which broke out during an election at Westminster in 1784 the Guards were called and the crowd fired upon. Two ladies lost portions of their wigs, several were ‘deprived of their eye-brows’ and one woman had her cork rump shot off.

Like all outrageous fashion, such excesses were ridiculed and portrayed in cartoons to humiliating effect. One caricature with the titillating title ‘The Bum-Bailiff outwitted, or the convenience of Fashion’ (1786) is a case in point, as well as epitomising the ‘false’ culture of Georgian society. According to Francis Grose’s Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1811), a bum bailiff was a sheriff’s officer who arrested debtors, no doubt alluding to the fact such debt collectors were always at a debtor’s back. At first glance it is easy to sympathise with the young lady portrayed in the clutches of the collector even if it is she who has run up an alarming debt by literally ‘buying into’ the trend that saw women wish to appear something they were not. But then the financial ruin brought about by investing in a frizzed wig, over-sized hat and false rump actually provides her with an escape. As the bailiff seizes her, warrant in hand, she slips free in her shift, leaving him holding her empty finery instead of her person. The caption reads:

The Bum Shop. (Library of Congress)

Suky like Syrinx changes shape,

Her vain pursuer to escape:

Ye Snapps, of Pan’s hard fate beware,

Who thought his arms embraced the fair

But found an empty Bum-case there.

Eventually, the cork rump faded in popularity, replaced by the Grecian silhouette and the Empire gowns of the Regency. It was probably the only time from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries that a woman’s hips were not encased in whalebone, padded with cork or engulfed in horsehair!

The Bum-Bailiff outwitted, or, the convenience of Fashion, published 6 May 1786 by S.W. Fores, at the Caracature Warehouse, Piccadilly. (Library of Congress)

The Honourable TOM DASHALL and his cousin BOB in the lobby at Drury lane theatre, an etching by G. Cruikshank, Illustrated London News, c. 1821. (Author’s collection)