Death by Crinoline

‘Even the prime minister has spoken out against the Crinoline in Parliament – they may as well have spoken out against gravity or the tides!’

Dundee, Perth & Cupar Advertiser, 1862

There was no more a contentious Victorian fashion, both for the ‘fair sex’ who wore it and the male population who were forced to accommodate it, than the crinoline. Even the corset with its propensity to give the wearer ‘tight-laced Liver’, as quoted in Dr Sir Frederick Treves’s The Influence of Clothing on Health (Cassell, 1886), or permanent disfigurement if worn at too young an age only affected the woman who wore it invisibly beneath her clothes. The crinoline on the other hand was ‘a monster’. Fathers and husbands hated them, politicians tried to legislate against them, Florence Nightingale decried them and employers banned them. Letters from angry readers about the ‘ridiculous skirt’ in the pages of top London newspapers and Punch magazine lampooned the fashion but to no avail.

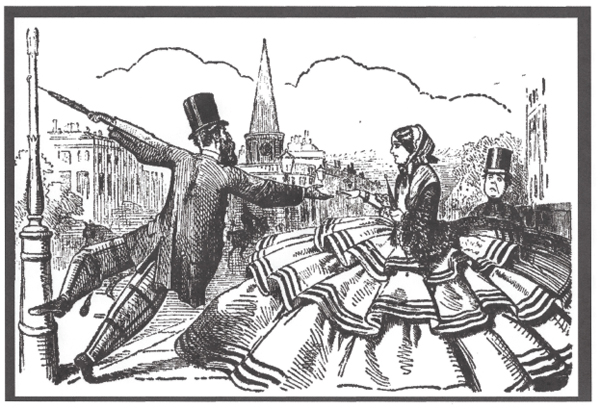

Crinolines effectively isolated women in a sea of fabric, Punch cartoon, 1856. (Author’s collection)

One Dundee newspaper reported, on 15 August 1862:

Crinoline has gone on expanding year by year till it has reached today’s preposterous dimensions. Expostulation is useless. You may reason with a lady about the expense of the fashion; you can appeal to her whether she finds the dress heavy and inconvenient and see how monstrous and indelicate it looks on others; you may point out how uncomfortable it is to walk by her side, that it precludes her from almost every rapid and graceful motion, stops her from moving in confined spaces; makes her a nuisance in an omnibus or carriage and even on public streets. You may as well talk to a stone.

In its condemnation of the latest female fashion the paper had certainly echoed what every man in the country was thinking. It went on to conclude: ‘Crinoline at present must be considered a necessary evil but hope it proves to be a temporary one’.

But what was so undesirable about a multitude of frothy petticoats designed simply to shape a skirt? The crinoline was in fact a cage encasing the lower body and distorting it into, at its peak, as reported in a contemporary newspaper, ‘a full domed contour akin to a tea-pot cover’. Popular for just over a decade from 1860, it grew in size until it was, among other things, totally at odds with the size of doorways. Town housing was becoming smaller, though no less cluttered, and it was to prove totally unsuitable for huge skirts or, in the case of families with many daughters and female servants, no less than veritable fleets of women in full sail.

Crinoline first appeared as a linen material interwoven with horsehair used for cloth petticoats; the French crin and lin, meaning horsehair and linen respectively. Gone were the soft high-waisted shapes of the first decades of the nineteenth century, diaphanous evening gowns and cotton and muslin day dresses which fell in a body-skimming column from just beneath the bosom. These were nudged aside by the reintroduction of the waist, albeit higher and wider. At last in 1856 the metal cage crinoline was introduced by the American W. S. Thompson. This lightweight support enabled ladies to wear just one petticoat to soften the cage ridges, and also saw the introduction of another new item of clothing, namely women’s drawers. Up until now there had been no need for such an undergarment as the weight of petticoats prevented skirts blowing about in the wind. These layers had steadily grown in number until by 1840 no less than six petticoats were normally worn and with no indication that such padding was likely to reduce, organ, flat and cartridge pleats had added even more volume, effectively bringing a woman to a standstill within her own clothes. Yet, now sporting no more than a lightly covered cage, a woman suddenly found herself having to grapple with that enemy of the crinoline, blustery weather and so to save her innocent blushes an appropriate undergarment was quickly found.

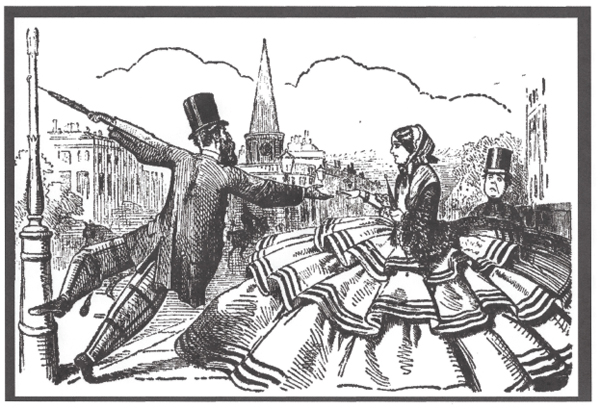

Dressing for the ball in 1857, from Follies of the Year: a series … from Punch’s Pocket Books 1844–1866 (London, Bradbury, Evans & Co., 1868). (Author’s collection)

An antique print showing ladies’ daywear, c. 1850s. (Author’s collection)

What made the fashion for the crinoline so popular was the fact it was universal, adopted by every woman in the Western world. In 1861 the Dundee Courier reported that even servants wore the skirt, and commented on its abject impracticality: ‘Unlike former times of hoops and vardingales the fashion has even descended to servants, so that where the dining room is small table maids have been known to give warning because they could not clear the space between the table and the fire and the newspapers are continually announcing “Accident from crinoline or woman burned to death”.’ The only difference seemed to be the quality of the crinoline across the social orders, with ugly ridges of steel bands visible through thin fabrics for wearers among the working class. Yet, young, old, fat and thin wore the hoop, and with such universal female appeal Sheffield, at the height of the crinoline’s popularity, was producing enough steel to equip women with ½ million hoops in one week.

In an effort to curtail its use it was once suggested the hoop should only be available for ‘mature’ women, matrons whose movements were less frivolous and so less of a problem for anyone within 6ft of them. Surprisingly, men had limited influence over their womenfolk’s adoration for the garment with warnings as to its dangers largely ignored by their wives and daughters. If they had taken more notice perhaps there would have been less of an outcry for the overblown and incredulous fashion, and fewer sorry tales of the disproportionate deaths and accidents to both male and female alike in the national and international press.

There is no doubt that accidents as a direct result of wearing a crinoline were more frequent than with any other garment in history. In addition, it was the only fashion where not only the wearer but also anyone within a short distance of them was at risk of disaster. Fire was the most common hazard with grisly accounts frequently appearing in the press. The death of Mary Anne Winterbotham, aged 22, was described in the Shoreditch Observer in 1861. She had picked up a shovel-full of burning coals to light the drawing room fire and placed it on the ground while she stooped to get wood from a cupboard. Her dress must have swept over the coals and as she was wearing a cane crinoline the garment rapidly caught fire. The jury returned a verdict of accidental death but expressed horror and disgust that someone whose household duties brought them in contact with hearth fires still chose to wear the inflated fashion.

Yet accidents could happen even when the lady in question was not performing a hazardous domestic task. In 1862 17-year-old Mary Anne Lane of Bedford found herself aflame when she stooped, ‘leant’, forward to dress her hair in a looking glass placed on the dining table. In doing so her crinoline billowed out behind her towards the lit fire in the grate, where the back of her dress was instantly engulfed. Despite her family at considerable risk to themselves tearing away nearly all of her clothes and wrapping her in a large quilt, she died from her injuries ‘and subsequent shock of having been badly burned about the legs’, as reported in the Worcestershire Chronicle on 14 May 1862. A year later it was reported that 16-year-old servant Maria Agnes Devonshire had died while wearing a crinoline. As part of her duties she washed the children’s faces in the mornings and as she stooped down her crinoline was forced between the bars of the fire grate. She instantly caught fire and ran in terror into the garden. Her master, hearing her screams, rushed into the garden but before he could extinguish the flames Maria had received fatal injuries.

Men complained bitterly in heartfelt letters to editors beseeching women to realise the dangers of their dress. One man raised his concerns in the Morning Post in 1861, signing himself simply ‘a father’:

The risks incurred every hour of every day by the wearer of a crinoline dress cannot be denied. Ingenuity is at a loss to devise a costume more dangerous from fire than this balloon-like apparatus attached to the female form. Our low open fire-places, candles, Lucifer matches, the simple act of sealing a letter, is pregnant with danger. Can any condemnatory of this detestable costume be too strong?

In 1864 a Dr Lancaster reported there had been 2,500 deaths in London alone from fire on account of the monstrous skirt. Reactions from the public were becoming noticeably weary, at times bordering on the impatient, ‘At all events if crinoline must be the fashion then every lady should wear a fire screen or at least be attended by a maid with an extinguisher’ was one terse suggestion. As early as 1859 Punch magazine reported that ‘Unless dresses are made fire-proof, no one, while the present stuck-out fashion lasts, can wear them safely. As a deterrent from wide petticoats we should pass an Act of Parliament to regulate their sale, and should permit none to be worn without being marked “DANGEROUS!”’

A look back at ladies’ fashion, Punch magazine, 1937. The original was by John Leech, 1859. (Author’s collection)

Punch also joked that were there ever a crinoline insurance company established it could not possibly withstand the constant claims, fire escapes should be provided in all drawing rooms and air tubes within the petticoat might all be filled with water (and a means to eject it) thus making every lady her own fire engine. Needless to say, none of these schemes came to fruition.

In June 1863 even something as mundane as climbing stairs posed a serious threat. Despite the introduction of strings, hinges and pulley systems attached to the underside of the skirt to help with raising the front of the hoop, the wife of a merchant still caught her foot in her crinoline and fell with such violence she fractured her skull. Even the genteel and sedate pursuit of archery became a hazard when in Hertfordshire the wife of a clergyman suddenly sat down on the grass snapping one of the steel hoops which supported her dress. The sharp end penetrated a tender part of her body and inflicted a severe internal wound. Another lady from Bath, while standing talking with friends, was unaware her dress was extending across a footpath and was accidentally dragged along the ground when a delivery cart drove past and its step hooked into her crinoline. Both of the woman’s legs were broken.

With women’s common sense refusing to prevail, men at least united against the hoop in satire and wit. ‘Men having tolerated crinolines long enough and patiently, are now claiming they have a right to comment on the situation …’, rallied one newspaper. Comment they did, gentlemen taking every opportunity to complain and commiserate with each other about how hard it had become for a man to live harmoniously with the women in his life while they were blindly in thrall to the ridiculous fashion, as revealed in this quote from the Era, Sunday, 24 May 1864:

Ladies cannot accuse us of intruding in any way upon the mysteries of the Female toilette in fact most men devoutly wish that the crinoline was indeed a mystery on the contrary it invades us on all levels in all places; at home and abroad, in the domestic circle, at the ball, opera, lecture room and at church in the streets on the omnibus is not every man made perfectly aware (chiefly through contact with his shins) that women as well as ships are ‘iron-clad’.

But it was not just a man’s dignity that was lost on contact with crinoline. Men were in danger of being killed by their wives’ and daughters’ skirts. In one instance when a man tried to pass a woman in a busy street, his foot caught in her crinoline and he fell into the gutter where a passing brewer’s dray ran over him, crushing his legs, Although taken to hospital, he died four days later, but during his time there, instead of blaming the driver of the vehicle in his report to the police, he wholeheartedly blamed the woman wearing the crinoline. In total agreement the lord mayor, hearing of this terrible accident, urged the police to exonerate the driver of the dray and prosecute the woman and her crinoline. The police never managed to trace the woman in question.

Accidents outside the home also proved fatal, proving there was no room for such a skirt in the workplace. In 1860, the textile firm Courtauld’s instructed their workers ‘to leave Hoop and Crinoline at Home’, but for one young woman, a 17-year-old factory worker employed, ironically, in a crinoline factory in Sheffield, there was no such advice. The Essex Standard of 1860 reported:

Sarah Ann Murfin age 17 – ascended a ladder to the upper floor to ask for a companion. The ladder was three feet from wall and between it and the wall is revolving shaft used drive machinery. Her skirt (much extended by crinoline) entangled in this machinery and she screamed for assistance but before shaft could be stopped. It whirled her round a great number of times her head and other parts of her body being dashed against the wall and the joists of the floor above & the ladder.

The poor girl was dead when they released her from the machinery, her skull dreadfully fractured, leg nearly torn off and body shockingly injured.

Even the invention of the collapsible crinoline did not prevent minor accidents or lessen fears in doctors. ‘The effects of wearing this weight of hoops and petticoats round the waist are dreadful …’, wrote one doctor in a letter to the London Standard in 1863, ‘Hernia has increased to a frightful extent and varicose veins and permanent and most serious injuries to portions of the abdominal area such as the public have no idea!’ He also added that were he a young man he would now hesitate to marry any girl, unless he could be convinced she was in a proper state of health, ‘… least I should find myself tied to a thing of hoops and petticoats whom I ought to have taken to the nearest hospital instead of to church!’.

Yet even in the house of God crinoline was unwelcome, denounced for taking up more space than churches could afford. One vicar strongly reminded his congregation that churches were not designed for the present exaggerated proportions of ladies and poured shame on those who by wearing the hoop prohibited the devout in his flock from finding a seat in order to hear the Gospel. In some cases reasons were more personal as one clergyman actually petitioned his council by letter asking for a by-law to be introduced which would directly help his position; either that or increase his stipend to accommodate the influence of the crinoline. He explained that he only earned £60 per year and as ‘crinolines make a dress very expensive and puffs up the female mind with unnecessary vanity …’ his daughter was putting him to enormous expense by the current inflated style of dress. Worse than that, his friend too ‘had eight daughters wearing hoops!’.

‘A Splendid Spread’ by George Cruikshank, The Comic Almanack, 1850. Such was the impracticality of the crinoline that at parties ladies had to be fed by their companions as it was impossible for them to access the buffet tables themselves. (Author’s collection)

For some it apparently proved too much and a Mr William Huntingdon, corn and flour merchant of Liverpool, was charged with ‘cutting away a ladies crinoline’ at the town assizes. It appears he had already assaulted two young ladies in Prince’s Park, Liverpool previously and cut off the crinoline of the elder one, exclaiming ‘These hoops, these hoops, I cannot tolerate them’, or words to that effect. He was actually acquitted to loud cheers, the support mostly coming from like-minded men who looked upon him as their champion.

But as much as people took against the fashion, with an Anti-Crinoline League existing for a while, there were those that wholeheartedly embraced the trend. In a letter to the editor of the Morning Post in 1861, one woman eloquently pointed out that as the crinoline was so popular and universal not to wear one would be ‘quaint to absurdity’. She also pointed out that the risk to crinoline from fire could be easily remedied without detracting from the grace or comfort of the fashion simply by changing the fabric used to make them from flimsy gauzes to wool and silk.

The fabrics produced in the present day are so many, so elegant and varied that there is no kind of difficulty in selecting dresses from 10 shillings to 20 guineas, perfectly un-inflammable and which if held close contact with fire would but slowly smoulder. My own and daughter’s dresses have during this winter repeatedly touched the fireplace so as to receive the impression of the grate and if they had been of lighter material I shudder to realise where we should now certainly be …

Rather than relinquish a dangerous and unnecessary fashion, she, while not wishing her daughters to burn, was obviously more than happy for them to ‘smoulder’!

Other positive effects accredited to the wearing of crinolines were revealed in 1858 when a girl named Martha Shepherd, attempting to commit suicide, leaped from the top of the balustrade of the bridge over the Serpentine in Hyde Park. She clearly had not thought things through as while falling her crinoline expanded to its full dimensions and ‘she came upon the water like a balloon floating there for several minutes’, as reported in the Ipswich Journal. A nearby constable was able to throw her a lifeline and as she began to sink he was able to pull her safely to the shore. Similarly, in 1864 a nursemaid on losing her way on the cliffs in Newquay, Cornwall inadvertently walked too close to the edge, slipped and tumbled toward the beach below, a fall of approximately 100ft. Following the laws of aerodynamics, her crinoline expanded with air and so broke her fall to such a degree that she landed without a scratch or bruise. Such occurrences may be in the extreme but on a more mundane note one young lady using her crinoline as a form of defensive armour was at least able successfully to save herself from a savage attack by an angry dog.

However much those in favour of the crinoline lobbied, there is no denying that in one area the crinoline caused a significant rise in crime. As the skirt increased in size so did the practice of shoplifting until both reached epidemic proportions. Ingeniously fitted out with pockets and hooks, it seemed there was no end to the size and weight of objects that could be successfully hidden under a crinoline. Female shoplifters found crinoline a ready and convenient hiding place for silk, fancy lace articles and even parasols!

Margaret Toole, a well-dressed woman of about 25, was charged, according to a newspaper report in 1862, with robbery at a draper’s shop. After walking about the shop looking at several articles, ‘her peculiar manner’ aroused the assistant’s suspicions and moments later she noticed some fringing hanging down from under the woman’s skirt. On calling for help, a policeman apprehended the woman not far from the shop and escorted her to the police station where it was found the woman had nine black silk mantles and two coloured silk dresses beneath her crinoline, all amounting to over £7. Needless to say, she was remanded.

Comical cartoon by John Leech, 1883. (Author’s collection)

Women crinoline thieves, however, were undeterred. Eliza Dreser, arrested at Hull police station, had become even bolder. Often remanded for stealing copious amounts of bed linen beneath her skirts, she lately was discovered to be hiding a set of steel fire-irons suspended from her waist. She protested they were her own but the police could find no reason why she should wish to transport such items in such a way and so she was charged.

From shoplifting it is only a short step to smuggling and a lady travelling on board a ship from Holland was suspected of such due to her strange gait while walking. Elizabeth Barbara Lorinz (a native of Holland) denied all charges, declaring she walked strangely due to pregnancy. On being searched, she was found to have no less than 5 pounds of cigars, 9 pounds of tobacco, a quantity of tea and a bottle of gin, all concealed beneath her crinoline. It was a similar case with Ellen Carey, whose arrest was featured in the Chester Chronicle of 1858. Described as ‘a neatly dressed female’, she was accused of smuggling 22 pounds of cigars within three large petticoats. As a passenger aboard the General Steam Navigation’s ship Moselle, it was only once the ship had entered St Katherine’s Dock and she was preparing to alight that she inadvertently alerted the Tide Surveyor, Mr Gardiner, with her ‘imense rotundity of dress’. When challenged, she explained that her ‘blown’ appearance was due to the crinoline, which every woman in the land wore and which she considered very becoming, whatever the gentleman thought on the subject. On being stripped of her skirts by a female searcher, the cigars were removed from her person and she was once more brought before her accusers, her size ‘greatly diminished’. Her smuggling had cost her a £100 fine and six months’ imprisonment.

Such instances simply fuelled men’s and some women’s abject dislike of the garment and put them under even more pressure to cope with consequences totally out of their control. ‘My wife and daughters cannot go on a shopping trip or enter a shop without the finger of suspicion pointed at them’ was the concern of one family man, followed by ‘my wife is looked upon as a potential thief every time she leaves the house!’ from another.

If women were aware of their menfolk’s dislike of their dress, they were doggedly determined to ignore it, be it at home or abroad. In 1857 the Liverpool Daily Post reported on a ball held at the Tuilleries in Paris and alluded to how one gentleman’s flattery was a cover for caustic sarcasm.

At one point a certain lady was watching with anxiety a gentleman’s approach across the ball room, her emotion becoming visible as he drew near, causing her in nervousness to spread out her already exorbitant skirt (which with the aid of boufants, flowers, flounces, and crinoline) filled the whole of the bench, burying beneath its ample folds two or three of her lesser dressed neighbours on either side.

As small talk gave way to the lady’s inquiry as to what her suitor thought of her dress that evening she received this reply, ‘Madam … I cannot but admire it for it recalls to mind the dearest souvenir of my soul’. ‘Indeed,’ exclaimed the lady her face brightening, ‘… and how so?’ ‘Why it reminded me the moment I entered the room, both in its extent and shape, of my tent in the Crimea!’

It was not only men who thought the battlefield no place for a crinoline. Florence Nightingale in 1863 warned her nurses against the use of crinoline on the grounds that if a modest woman knew the spectacle which she presented to her patients when bending over a fire, with expanded dress, she would forever renounce the obnoxious vestment. ‘We don’t want to go back to the high waists and scanty dresses of our grandmothers, but surely there is a happy medium?’

English steel produced the best wire for the crinoline cages. After being softened in a furnace it was scoured in acid to remove its oxidised surface, then coated with rye and flour then specially dryed. The steel, initially in thick, short rods, was then lengthened to no less than 2,000yd in order to reduce its width to ¾in, then hardened and tempered before being braided in yarn and sent to the warehouse for use in skirts. No less than 60,000yd of flattened steel wire were produced daily via this process. Ultimately made into coiled hoops, these were suspended by tapes in the form of a skirt, descending in increasing diameters from a band worn around a woman’s waist.

‘A Woman in a Corset is a Lie, a Falsehood, a Fiction, but for Us, this Fiction is Better than the Reality’ – Eugene Chapus

It is accurate to say that the crinoline was a revolution in women’s fashion, and the far-reaching consequences of which rivalled that of even the Crimean War. However, the tortuous corset, pristine, unseen and in many cases deadly, in contrast compressed the female into a fashionable 17 to 22in waist at the cost of health, beauty and ultimately of life itself.

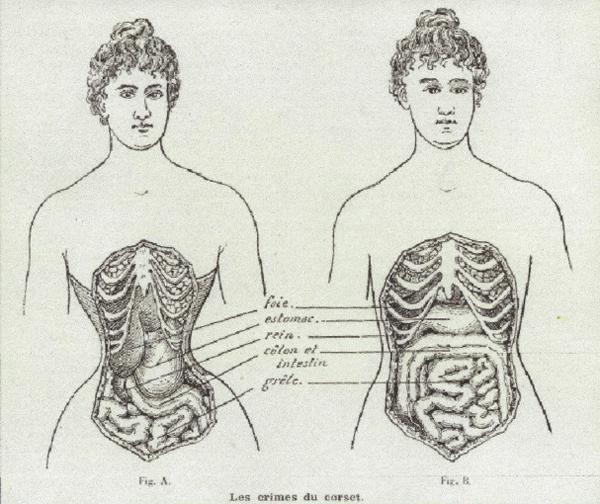

It was no wonder that Victorian ladies ‘swooned’ so frequently. Prolonged corset wearing meant the internal organs were unable to grow in their natural position and there were fears that a woman’s lungs could not function properly and that her liver could be almost cut in half. The historical horror stories are appalling. One 23-year-old Parisian woman at a ball in 1859 proved to be the envy of all with her 13in waist; two days later she was found dead. An autopsy showed that her liver had been punctured by three ribs. A chambermaid who said she had extreme stomach pains was also found dead soon after; her stomach was nearly severed in half ‘leaving a canal only as narrow as a raven’s feather’. Medical men constantly argued against the corset and if a woman died in mysterious circumstances and was slender figured, a doctor would look for ‘tight-lace liver’, a malformation of the organ that signified to him the lady in question had been guilty of tight-lacing. It was also usual that doctors if suspecting ‘tight-lacing’ kept the fact to themselves to avoid publicity and scandal.

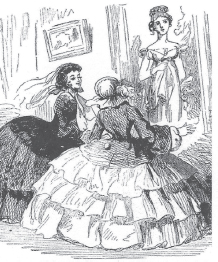

‘Arabella Maria: “Only to think, Julia dear, that our Mothers wore such ridiculous fashions as these!” Both: “Ha! ha! ha! ha!”’, Harper’s Weekly, 11 July 1857.

A crime of fashion. (Wellcome Images)

To be fashionable women have always made their waists smaller than they should be. It was only really in the nineteenth century that we can see the damage this did by reports appearing in newspapers warning the universal female about exactly what she was doing to herself in the name of vanity. Women had always fainted from being ‘over laced’ and it was a wise woman who did not conform to a hand-span waist. With improved literacy and newspaper circulation reports of extreme cases could be held up as warnings to those who would listen.

As early as 1829 reports appeared in newspapers concerned with the effects of the compression of the waist in females by the use of corsets. Pictures were also provided. It was hoped that a glance at the graphic details would bring about the change that words alone could not. A Devon newspaper published the following:

A Victorian corset, 1899. (Library of Congress)

Those who have long so closely laced become at last unable to hold themselves erect or move with comfort without them. The muscles of the back are weakened and crippled and cannot maintain themselves in a natural position for any length of time – the spine too no longer accustomed to bear the destined weight of the body bends and sinks down. Where tight lacing is practiced young women from 15 to 20 years of age are found so dependent upon their corsets that they faint whenever they lay them aside and therefore are obliged to have themselves re-laced before going to sleep. Or as soon as the Thorax and abdomen are relaxed by being deprived of the support the blood rushing downwards in consequence of the diminished resistance to its motion empties the vessels of the head and thus occasions fainting …

It was quite astonishing just how many diseases were attributed to tight lacing: head-aches, giddiness, fainting, pain in the eyes, pain and ringing in the ears and bleeding at the nose. In the thorax, despite the displacement of the bones and the injury done to the breast, tight lacing also produced shortness of breath, spitting of blood, consumption, derangement of the circulation, palpitation of the heart and water in the chest. In the abdomen it caused loss of appetite, squeamishness, vomiting of blood, depraved digestion, flatulence, diarrhacolic pains, dropsy and rupture. This could be followed by melancholy, hysteria and many diseases peculiar to the female constitution. It also produced what no self-respecting Victorian woman wanted – a red nose!

In 1871 the Metropolitan magazine ran a scathing headline which read, ‘The size of the waist is more important than the size of the brain’, but it appeared to have little effect. In 1881 a post-mortem on a woman named Amelia Jury, aged 43, presented a stomach constricted to an eighth of its natural size with a liver flattened and driven down deep into the pelvis. An autopsy carried out on a woman in 1895, who had mysteriously died in a dentist’s chair while having a tooth extracted, showed her liver to be divided into two nearly equal parts united only by a thin channel due to tight lacing.

On a slightly lighter note, one gentleman, expressing his concerns in newsprint (complete with a diagram), wished to to make clear to ladies that their efforts to be small-waisted were not in their control at all and that female attractiveness depended entirely upon a system he himself had concocted using nothing other than algebra.

A beautiful young lady died the other evening of an inflammation of the internal region caused it is believed by the tight lacing of her corset. Let this be a warning to all fair creatures who are now tightening their corsets till their cheeks get flushed and their eyes lose all their softness and affection.

Tight lacing injures the facial beauty of a female more than they imagine. It is a mistake to imagine that a narrow female waist is so attractive in the eyes of a man. We assure our female readers that it is no such thing. We speak from feeling sentiment and natural impulse.

The slender waist is no essential element of beauty – it is part of a much wider attraction. It is necessary only to be in proportion to the rest of the female form, the whole beautiful region, the soft white neck, the pouting lips the rosy cheeks, the melting eyes and glorious angelic forehead. Milliners and corset makers who presume to set the fashions do not understand the mathematical elements of beauty that enter into the composition of graceful female forms. Among philosophers the whole theory of perfect beauty is explained in the following interesting algebraic problem … if we assume …

| X | Represent the female bust |

| Y | Its diameter |

| = | Its proportions |

| Lm | A narrow waist |

| Ab | The rest of the angle |

The x, y, = added to ab will be equal to the most beautiful woman that graces any salon or square – while a narrow waist only leads to death and melancholy. We trust therefore that every young and beautiful lady will study this problem and come to the inevitable conclusion that a narrow waist is not an element of beauty and grace but a principle that leads to unhappiness, pain and consumption, and finally death.

An endearing sentiment to all intents and purposes, if not a little self-serving and somewhat sexist to the modern ear?