Bustles

‘The customs officers at Queenstown on Monday arrested a passenger from New York because she had a revolver and 20 ball cartridges concealed in her bustle.’

Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette, 1888

If Florence Nightingale called for moderation in a woman’s dress it was only to fall on deaf ears. Encased in their corsets and unwilling to forego the yards of beautiful fabrics that once covered their hoops and which they had fought so hard to retain, women, with stubborn gentility, simply flattened the front of their skirts, and gathered everything up at the back into one enormous lump resulting in the equally ridiculous fashion, namely the bustle. As if that were not enough, as the century drew to a close corsetting managed to winch the female form into ever more sinuous shapes until by Edwardian times the infamous ‘S’ bend corset bordered not so much on the ‘feminine’ as the fatal.

From 1870 to the beginning of the First World War the female form underwent no less than four distinct – and equally uncomfortable – shape changes. As the crinoline quickly fell out of favour, after 1869 the female silhouette morphed from a wide shape to an upstanding one. At first tapes and ribbons were used within the skirts to achieve the new flat-fronted look by tieing and looping swathes of fabric up behind them. However, once the fashion was established women began to add more and more fabric over what was known as a ‘shape improver’, better known as a ‘bustle’ or a Grecian bend.

The latest French fashion, The Ladies’ Treasury.

The first or early bustle era lasted for just under a decade from 1869 to 1876 and was a much ‘softer’ affair (literally) than when the fashion re-appeared with a vengeance some years later between 1883 and 1889. In this, the bustle’s first incarnation, a gently rounded derrière was created by the strategic placement of small ‘cages’, cushions or pads, stuffed with horsehair, down or even straw. Just as with the crinoline, bustles were often ridiculed in the press but unlike the former which was hazardous for life and limb to all who came in contact with it, the bustle was only uncomfortable for the woman who wore it.

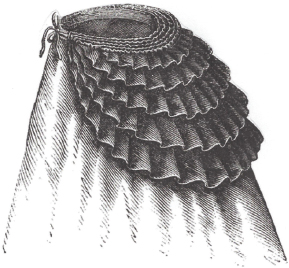

A horsehair bustle, 1868.

A Jupon or Tournure, 1887.

In the Stamford Mercury, dated Friday, 1 May 1874, an advertisement for Thomson’s novelties offered, at reasonable prices, the Corymbus, a new bustle patented and made from Chinese plaited straw. It made no bones about the fact it definitely contained ‘no steel’, a feature also of the Rouleau and the ‘Grasshopper’ Tournure (a device used by women to expand the skirt of a dress below the waist) and which would produce the very latest outline. It seems a strange phenomenon today that we were ever not in control of our own outlines and had to look elsewhere to see what we would be looking like in the near future.

Between 1877 and 1882 a far more slender silhouette became the norm, with the early bustles diminishing to leave slim hips and only a shaped petticoat to support a new trained skirt. Ruching and pleated frills emphasised the fullness of the back of the skirt but often the dress itself was so narrow a woman had to limit her stride to almost nothing. What was also evident was that to carry off such a slender style a woman had to be very slim indeed, a feat often achieved by wearing a very tight corset.

As a backlash to all this drapery a push towards simpler styles of dress was making itself known. The 1870s saw the rise of the Aesthetic Movement, which under the influences of poets, painters and actors called for beauty and grace in all things, not just dress. Its members abhorred ugliness in what they saw as products of the Industrial Revolution, rallying against harsh aniline dyes responsible for gaudy colours and called for, among other things, a stop to the use of the sewing machine which they held responsible for all the frills and flounces that masked a woman’s true attractiveness. Influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne Jones, the movement held up medieval women, free of corsetry and in ethereal surroundings, as a perfect example of natural freedom. It was an ethos based primarily on aesthetics. The Rational Dress Society was formed in 1881 and was a second call to arms for those who thought it prudent, no essential that the beleaguered female was rescued from the imprisonment of her clothing and the damage it was inflicting on her health.

Advocates of practical fashions, it was Viscountess Harberton and a Mrs King who drew the nation’s attention to how corsetry restricted free movement and was, if taken to extremes, fatal. On 26 March 1886 the Viscountess presided over a very well-attended lecture at Westminster Town Hall and spoke on the absurdities of feminine attire, how it was modelled upon a distorted ideal and dwelt upon the physical consequences of tight dresses. Expressing her concerns, she suggested that it was ‘habit not usefulness or grace’ that controlled the fashion and it was for that reason the society wished to arouse in the female mind more ‘sensible aspirations’. She also explained that in her opinion tight dresses gave women high temperatures and as they also prevented exercise they were the reason so many English ladies of middle age were ‘so deplorably stout’. She argued against ‘the monstrosities’ forced upon women by dressmakers and those in the ‘trade’ and was adamant that there should be reform, from ‘boots to bonnets’, and convinced that once the Society had enough members then opposition to women being free and safe in their clothes would melt away.

An original hand-coloured lady’s fashion plate from Der Bazar magazine, 1885. (Author’s collection)

The second bustle era gave ladies a curious silhouette which made the wearer’s ‘derrière’ resemble the rear end of a horse. Ladies Journal. (Author’s collection)

One suggestion of the Rational Dress Society was to embrace a divided skirt, but it was not universally accepted as women reasoned, quite rightly, that a divided skirt, made with enough material to make it resemble a full skirt was counter-productive, just as heavy and therefore pointless. Possibly the greatest recommendation of the Rational Dress Society was that a woman’s dress should weigh no more than 1½ to 3 pounds and that her underwear should weigh no more than 7. To the modern woman who wears silk or synthetic lingerie as opposed to bulky cotton, wool or flannel this is still a great deal of clothing, but that figure was actually half of what was worn by most women in 1850 when ladies were restricted by up to 14 pounds of layered undergarments.

Among those who subscribed to the principles of the Aesthetic Movement and the Rational Dress Society was none other than the famous writer Oscar Wilde, who was more than happy to have his feelings known in an essay which appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette on 14 October 1884:

all the most ungainly and uncomfortable articles of dress that fashion has ever in her folly prescribed, not the tight corset merely, but the farthingale, the vertugadin, the hoop, the crinoline, and that modern monstrosity the so-called dress improver also, all of them have owed their origin to the same error – the error of not seeing that it is from the shoulders, and from the shoulders only, that all garments should be hung.

These attempts to change women’s dress had their devotees but in 1883 bustles came back with a vengeance, perhaps because some ladies thought ‘women were disgusting creatures without one’. However, it was more likely to have been because Charles Frederick Worth, the designer who dominated Parisian fashion in the latter half of the nineteenth century, re-introduced the phenomena, and though skirts remained slim in front and at the sides, the back ballooned out like never before. Suddenly women were jutting out behind larger than ever and with a silhouette that made them look like they had inherited the hind legs of a horse! To remedy the difficulty in sitting, a spring-loaded bustle called a ‘phantom’ appeared in 1884, promising ultimate comfort as its steel wires were attached to a pivot that folded in on themselves when sat on and which sprang back when the wearer rose. Less useful was a similar novelty bustle made to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee celebrations, which was fitted with a musical box that played ‘God Save the Queen’ each time the wearer sat down.

Not about to let an opportunity pass, by 1886 companies were adding to these phenomena with the concept of a ‘handbag bustle’, first advertised in the Manchester Evening News. To all intents and purposes, said the manufacturers, its outward appearance was one of an ordinary bustle but inside there was ‘a large compartment in which a lady can carry articles such as brushes, cosmetics, tooth preparations and night raiments she may require when on a short visit, or temporary absence from home’. The idea of a lady going about with her luggage in her bustle was possibly as startling to her as it is to us, but it was a great selling point and would save a woman from the problem of a lack of pockets which men did not suffer from.

The idea that bustles could double as capacious receptacles for storing items was exploited for both good and the clandestine. In 1886 a woman sorting rags at St Mary Cray Paper Mill found French coins and notes to the value of £40 in a lady’s bustle, while there were reports that love letters, a gun and smuggled ammunition had been found in others. The police, out on a mission to apprehend a gang of notorious poachers, were nothing if not surprised when waiting for the men to return home with their ill-gotten gains the villains actually met the constables empty-handed. What did surprise them was that not long afterwards three women appeared to have followed them with a ‘suspicious display of bustle’. On investigation, this turned out to be due to the presence of twenty-seven rabbits and two long lengths or rabbit netting. The police later commented that the inventors of a garment capable of covering such a multitude of sins had a great deal to answer for.

Alternatively, a bustle could be a cause of surprise for the unsuspecting wearer as it was for two American sisters, Misses Mamie and Della More from Pocomoke in Maryland.

After walking on their farm the women rested on a log and became engaged in conversation long enough for one sister to become aware of a heavy weight which seemed to drag her dress down behind. Asking the other to see what the matter was, the latter, after some investigation and to the horror of both women, discovered a large copper-head snake had coiled up in her bustle. Despite the snake measuring 5ft long and being as thick as a man’s wrist, the ladies dealt with the intruder and continued unfazed about their business.

A similar occurrence happened to a woman in England, who after having ordered a bustle to be made for her, found it on completion to be a little too big to be fashionable and so had tucked it away in her attic until such time as it would again come into vogue. Luckily for her, it did but when she retrieved it she found it was now home to a family of house mice whom she did not have the heart to evict. Subsequently, she wore it, mice and all, the only alteration she made being a hole in the side of her bustle and her skirts so she could feed the small creatures at her dinner table which equally amused and terrified her guests.

Punch’s designs ‘After Nature’, snail bustle, 1870s.

On Saturday, 29 September 1888 an article appeared in the Aberdeen Evening Express detailing the strange incident of an exploding bustle. The incident happened in America in the Congregational Church of San Fransisco during a reading given by none other than novelist Charles Dickens. It appeared that a lady with a ‘dignified gait’ was accompanied by her husband, a military man, into the building whereupon they both found their seats. The lady gave a graceful swing to her skirt in order to sit down gracefully but at that moment a muffled but loud noise came from beneath her dress and the lady ‘was observed to collapse with a lurch’. She turned deathly pale and got up looking intensely embarrassed and confused. At this point Mr Dickens stopped reading and looked up to see what was the origin of the small explosion, but finding nothing serious had happened returned to his oration. By now smiles and titters had begun to circulate the room by those who had a good idea what had happened. Unfortunately, her husband was not of a sympathetic nature and grasped his wife’s arm roughly and told her not to act so foolishly. But the explosion of an inflatable bustle is no small matter to a lady and covering herself as much as she could with her shawl to hide her blushes she did eventually agree to stay for the evening but felt very uncomfortable doing so. Later the lady brought a law-suit against the dressmaker who made her bustle, accusing her of negligence. The dressmaker defended herself by saying that she had indeed made the bustle for her customer, several bustles in fact, in the hope that at least one would fit her as she seemed to have changed size everytime she saw her. One was deemed suitable but it was written into the contract between the dressmaker and the purchaser that the latter would not sit down suddenly and would adhere to these instructions religiously. This had obviously not been the case as the rubber bustle had indeed burst causing injury and distress to the wearer. The judge giving his decision on the merits of the case responded with the following.

‘This is a most peculiar case. I have read of bustles being made of horsehair, muslin, newspapers, pillows, bird cages and even quilts. I have heard of alarm clocks striking the hour within the folds of a ladies dress. Smuggled cigars, jewelry and brandy have also been brought to light but I have never before heard of an airtight bustle exploding in church and then being made the subject of a civil suit. Not being married yet, the situation is somewhat perplexing to me, but still looking at the case from a legal standpoint, I think we can adjust matters satisfactorily. Were a non-explosive bustle used, this suit might never have been brought.’ His honour then deducted a negligible sum from the bill of the dressmaker as the defendant set up a claim for damages for the explosion trouble. He then rendered judgement in favour of the plaintiff.

Undeterred by potential disasters, one woman vehemently defended her right to wear what she wanted and wrote to the Royal Cornwall Gazette in September 1888 to justify herself.

I wear a bustle and believe in it. I wear a large bustle and I am proud of it. I wear a steel ribbed, brass riveted, burglar and fire proof bustle, and it is a joy beyond compare. I have tried all varieties of bustle – the large and small, the round, a flat, the soft and the substantial. My experience makes me friendly to the large bustles, and the stronger they are the better I like them. The only bustle I detest is the four-cylindered affair filled with spiral wires that look like a quadruplex fire hose. The cylinders are worn vertically and if you are not careful in sitting down when you have one of these fixings on you are likely to be catapulted into the empyrean. It requires a woman of great and everlasting presence of mind to sit down properly in the 4 cylindered bustle.

I have heard time and again that men wonder how women manage to sit down wearing a bustle. The secret is that when a bustle decked women sits down she does so carefully and does so sideways. There is a pretty little trick in it. She pretends she is going to sit on the right side of the chair and makes her first movement in that direction; but just as she reaches the chair she moves gracefully to the other side, the bustle rolls to the right completely out of the way of the sitter and the problem is solved.

By the late 1880s the hard armour-like bustle was in decline, replaced by softer shape improvers which nevertheless had their downsides. On Monday, 16 January 1888 the Dundee Courier strongly suggested that ‘Ladies Beware!’. It went on to explain how a young lady who had attended the Marlborough Races wore with pride a new and improved ‘dress improver’ stuffed with bran and straw. While witnessing the races she was unaware that a hungry nag stationed behind her had smelled the stuffing and thinking it for him unceremoniously tore the dress to pieces, leaving the woman in complete disarray in his endeavours to eat its contents.

Lady’s Pictorial Magazine, 15 July 1893. (Author’s collection)

Just as crinolines before them, bustles did not meet with approval in the workplace. In 1888 in Huddersfield an ingenious manager of a shirt factory issued a mandate against the wearing of bustles by his employees and justified his draconian law by the following calculation:

a girl will arrange her bustle 5 times a day, occupying one minutes time whenever she does so, and that makes a loss of 5 minutes. Where there are 12 girls it means the loss of an hour. Then they will leave the shop 5 times more which takes five minutes each time. That makes 25 minutes or you might say half an hour. 12 girls, each losing half an hour means a loss of 6 hours, added to the bustle hour makes 7. This means a great deal of money when you are paying girls by the week. Taking the bustle-wearing population of London as 1,000,000, the daily loss of time at this rate in London alone is equal to more than 50 years!

There had always been a danger that a bustle/pad or dress improver could become loose, slew around the body and make a lady look decidely lopsided! But as the 1880s slipped into the 1890s the bustle began to fade until only a small pad was left to be replaced by a long-bodied, heavily boned corset. Gwen Raverat, the granddaughter of Charles Darwin, touched upon the realistic discomforts of wearing corsets in her classic memoir of a Cambridgeshire childhood called Period Piece, published in the 1950s.

the ladies never seemed at ease … For their dresses were always made too tight, and the bodices wrinkled laterally from the strain; and their stays showed in a sharp ledge across the middle of their backs. And in spite of whalebone, they were apt to bulge below the waist in front; for, poor dears, they were but human after all, and they had to expand somewhere.

The demise of the bustle necessitated drastic action from an Australian draper, whose story appeared under the heading ‘A Sea of Ladies Bustles’, reported in the Liverpool Echo on 16 June 1893.

The Melbourne drapers who have large stocks of unsalable bustles on hand are now busy throwing the obsolete feminine adornments into the sea. The only way to recover the import duty paid on them is to re-export so the bustles are exported accordingly and when the vessel gets out to sea they are heaved overboard. The sea is dotted all over with bustles and sometimes they even come ashore.

Once again attention was focused firmly on the waist and from now on it would be the ‘S’ bend corset that would straddle the decades either side of the twentieth century and set the Edwardian silhouette.