La Belle Époque

‘… when Paris seemed to be the artistic center of the universe’

Merriam-Webster Thesaurus

The previous century had produced crinolines, bustles, frills and flounces of every description, but now under a new monarch and a new modern way of thinking Victorian Britain was fading and the belle époque (beautiful era) had arrived. Edward VII’s reign was to last just a fraction of his mother’s but it had no less impact on the world of fashion. In fact, he and his wife Princess Alexandra had already been influencing fashion for at least a decade, together setting the tone for society which was copied and adapted by those of lower standing and income.

In some areas fashion had slowly been taking notice of the new clothes movements and a new ‘tailor made’ range of clothing developed to cater for, as the magazine Punch put it, the ‘New Woman’. A new generation of energetic and active young women who indulged in outdoor pursuits such as cycling and were being employed in an ever wider range of white collar jobs, they embraced the new idea of ‘separates’, namely a plain ‘suit’ consisting of a skirt with a jacket-bodice or contrasting shirtwaist or blouse devoid of heavy boning. In addition, the hemlines of all walking skirts in the 1890s rose a full 3in off the ground, creating the ‘Rainy Daisy’ style, so-named because the hems could now be kept dry on rainy days. The widespread adoption of the blouse was arguably the greatest development in dress in the 1890s. It allowed a more versatile style of dressing – one skirt could be worn with a number of different blouses, suitable for different occasions. It could also be purchased ready-made, as the fit was not as important as that of a bodice.

Yet, as with most fashion, just as something sensible comes along to advance a trend then equally something comes along to counter the advantage. With the ‘Tailor-Made’ it was the reintroduction of the ‘Gigot’, better known as the ‘Leg o’ Mutton’ sleeve. These had first made an appearance sixty years previously in the 1830s, when it was more commonly called the ‘beret’ sleeve’ which extended flat from the shoulder and had a downward droop which needed stuffing or steel wires inserted to support it. This new modern adaptation was far more upstanding, beginning as a small puff at the top of the sleeve. Set high on the shoulder in 1892, by 1896 the ‘Leg o’ Mutton’ had reached monstrous proportions projecting confidently upwards and outwards (some say to reflect the growing aggressiveness of women) and needing stiff interlinings to hold a good shape. Perhaps women adopted them because they genuinely liked them; the fact they made one’s arms resemble two lamb shanks being purposefully overlooked. It is more probable the sleeves had the effect of alluding to a hand-span waist by way of evening out the shoulders. Another trend, the puffed sleeve, which was a short, three-quarter or full-length arrangement, sometimes called the Bishop sleeve, also had the same waist-slimming effect.

By 1899 the charm of the enormous sleeve was lost and only a slim, tight sleeve remained with a few gathers at the top to hint at its former glory. But not all mourned their passing as it was remarked upon by a journalist for the Wells Journal that ‘some ladies are taking very badly to the newer and tighter sleeves. They have a pinched, impoverished sort of look to the eyes which have so long been accustomed to the breadth and importance of Leg o’ Mutton’s …’. Taking the opposite view, it was said that there was a general consensus among women that they were only too glad small sleeves had finally taken over as they did not want to go back to the previous monstrosities. The main reason for this being that they could once again rejoice at the ease with which their dress sleeves slid inside their jackets!

Tailor made separates of the 1890s, Lady’s Pictorial Magazine, July 1893. (Author’s collection)

As strict Victorian attitudes began to recede the early twentieth century was bowing to common sense and simplicity in fashion and, though details were still elaborate, overtly fussy trimmings and unnatural lines were gradually being abandoned. This trend of simplicity would ultimately be intensified and accelerated by the First World War, which would for the first time in history establish two great principles in women’s dress – freedom and convenience. Until then there was still a way to go. Trends may have been changing but dressing in Edwardian times was still something of a rigmarole. The day would begin with a woman choosing what undergarments to wear from the numerous sets of ‘lingerie’s’ comprising day and night chemises, drawers, knickerbockers and petticoats, after which she would be laced into either a straight-front or an ‘S’ curve corset. Tailored morning garments were probably the day’s first choice of garment – a smart blouse and gored skirt perfect for walking, shopping or meeting friends. Returning for lunch would necessitate a second change of clothes, this time into an afternoon dress and by 5pm relief was at hand as she could struggle out of her corset and into a tea-gown, which was generally accepted as a delightful informal affair, often white cotton, extremely comfortable and described in The Times of 1912 as ‘quite the most becoming garment in which a woman can be arrayed’. A dress ‘of intimacy, and not to be worn in crowds’, it was the perfect garment for lounging and receiving friends. By 8pm, however, it was time once more to be encased in whalebone, possibly after a change of lingerie (and stockings – cotton for day, and embroidered silk for the evening), and then an evening dress, the degree of ornamentation depending if you were going out or not.

Contrary to popular belief, even those in society did not always relish the constant change of clothing, as many Edwardian memoirs recount. Cynthia Asquith wrote:

A large fraction of our time was spent in changing our clothes … particularly in the winter, when you came down to breakfast ready for church in your ‘best dress’. After church you went into tweeds. You always changed again before tea into a ‘tea gown’ if you possessed that special creation: the less affluent wore a summer day-frock. Thus a Friday to Monday party meant taking your ‘Sunday Best’, two tweed coats and skirts, with appropriate shirts, three evening frocks, three garments suitable for tea, your best hat – rows of indoor and outdoor shoes, boots and gaiters, numberless accessories in the way of petticoats, shawls, scarves, ornamental combs and wreathes …

Petit Echo de la Mode, 3 February 1895. (Author’s collection)

Cynthia was also honest enough to admit at times she detested her clothing, unheard of in a society hostess:

Many of our clothes were far from comfortable or convenient. Country tweeds were long and trammelling. Imagine the discomfort of a walk in the rain in a sodden skirt that wound its wetness round your legs and chapped your ankles. Walking about the London streets trailing clouds of dust was horrid. I once found I had carried into the house a banana skin which had got caught up in the hem of my dress. I hated the veils that, worn twisted into a squiggle under my chin, dotted my vision with huge black spots like the symptoms of liver trouble. They flattened even my short eyelashes. Our vast hats which took to the wind like sails were painfully skewered to our heads by huge ornamental hatpins, greatly to the peril of other people’s eyes.

The ‘S’ bend corset managed to contort the female frame into an almost impossible shape.

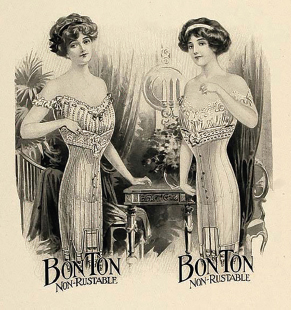

An advertisment for a ‘non-rustable’ corset by Bon Ton, 1913.

An ‘S’ bend corset.

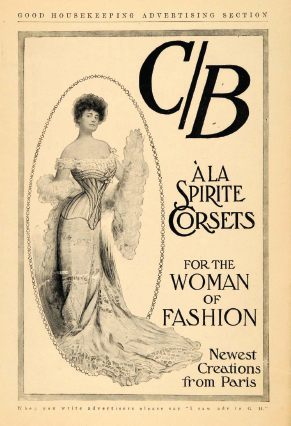

A corset advertisement from Good Housekeeping.

Edwardian society revolved around the London Season which ran from February to July, and necessitated a twice-yearly shopping trip to London or, if seriously wealthy, Paris. During the months of March and later in September, droves of women could be seen descending upon shops and fashion houses where a personal vendeuse would help them choose six month’s worth of wardrobe for the coming season, and seamstresses would work away feverishly in the backrooms.

But none of these outfits would have produced the right effect without the corset of the moment, mentioned previously, the ‘S’ bend. It differed from the circular wasp-waisted ‘swan-bill’ corset of the 1890s with its divided bosom, called a ‘divorce’, and was instead a straight-front corset with an elliptical waist line which forced the torso back into a curve, leaving the breasts pushed forward and unseparated. This created the familiar mono-bosom look of the Edwardian era with this particular corset hailed as being less constricting and more comfortable as well as being able to produce a tiny waist. As a rule of thumb a woman’s waist was supposed to measure, before she was married and had children, the same as her age in years! Advice was also at hand from many sources for those whose waists had not returned to a pre-childbearing hand-span and who needed a little help. Bertha Hasbrook wrote:

For the stout women … corsets will ever be a matter of vast moment. She is dependent upon the corset for whatever grace she has. It can save her from the flabby look she dreads by day in her waking hours and by night in her dreams. It can turn her flesh to a pleasing firmness of contour, something at least stylish if not exactly in accordance with poetic ideals. The wrong corset, on the other hand, will ruin her last change of good looks. It will show her at her very worst, revealing her faults and exaggerating them.

But she must bear in mind this fact: the flesh that is hers cannot be removed by any corset made. If pressed beyond the endurance of Nature in one spot, it is bound to go somewhere. So don’t expect to have it vanish at the magic touch of the corset lace. If you reduce your waistline beyond what you have a right to do, the flesh will be forced up and give the appearance of an atrociously large bust. The thing that a corset will do is to hold the flesh firmly in its proper position and prevent its sagging in the manner which is so unpleasant to see.

One can only imagine the comfort such an address would have given the well-endowed!

Sherman’s Excelsior corsets supposedly enabled the wearer to be comfortable in every position. Proposing to help form already youthful figures by not ‘repressing every charm’, it would also hide the ‘irregularities’ of an older shape so that no ‘defects’ would be detected. Even a figure considered ‘bad’ by the corset would seem ‘good’. Comfort, health, deceit. What woman could ask for more?

Perhaps it was the function of the huge Edwardian hats to remedy an imbalance of figure. As the bonnet had disappeared in the 1890s, hats gradually grew wider as the era progressed, the ‘Merry Widow’ hat, of 1907–8, after a play of that name, retaining its popularity until 1914. There is debate as to what actually came first in this matter, the large hat to adorn the hair or the large hair to support the hat. Whichever, it is certain that women’s hair certainly contributed to the overall hat silhouette and hairdressers created Pompadour supports as bases over which women could build their hair. Combings from hairbrushes were also regularly stored to make up a matted pad or roll called a ‘rat’ which was pinned in place and over which the top layer of hair was smoothed to create the full luxurious effect.

An Edwardian French corset advertisement for ‘elegant women’, a marvellous undergarment for the tea-gown obtainable from Mme Desbrueres, Maison ‘A Jeanne d’Arc’, 265, r St Honore, Paris. (Author’s collection)

Le Journal des Modes. (Author’s collection)

Edwardian Actress Lily Elsie in a large hat and high collar. The hat was named after a famous play at the time, The Merry Widow. (Author’s collection)

Hats which looked as if they were merely resting upon an elegant head were in fact anchored fast to a veritable nest of hair with hat pins often up to 13in long. Laws against hat pins of ‘excessive length’, or the wearing of them without protective stoppers, were proposed if not implemented in London, New York, Hamburg and Berlin as hat-pin-related injuries became common for both the wearer and unsuspecting fellow passengers in crowded places. Hat pins were also popularly regarded as every woman’s weapon against the unwanted attentions of hooligans and ill-mannered brutes, giving rise to a risqué music-hall ballad, ‘Never Go Walking Out Without Your Hat Pin’.

For modesty’s sake women’s clothing of this era was as complicated on the inside as it was beautiful on the outside with tapes and ties fastening one item of clothing to another, such as a blouse to a skirt with hooks on the waist to prevent the exposure of any skin should the arms be raised. It was almost a contradiction in terms, however, as the blouses in question were often soft and clinging, elaborate confections of ribbons and chiffon and other gauzy fabrics. The aptly titled ‘pneumonia blouse’, with its seductive and almost transparent V-shaped yoke at either the front or the back, was considered quite immodest as its tantalising open work showed glimpses of ‘delicate’ skin. In America it caused more of a stir than in Britain. Whereas here we thought it added to a young woman’s irresistible bewitchment and charm and kindly detracted from a mature lady’s tell-tale lines, in Massachusetts in 1906 it met with protracted opposition from what was known as the Purity Brigade.

Where skin was allowed to be shown it was usually that of the shoulder, with beautiful evening gowns designed to be wide-necked to better show them off. With shoulders an important focus point, advice was on hand to those who relished beauty tips not unlike today where women are told to rub oil into damp skin to retain youthful moisture. Today we would probably not follow the advice of one newspaper, which recommended that after washing the shoulders in hot water we should ‘dry very slightly, and while the skin is still moist should rub in a little glycerine and rosewater, and then dust heavily with a good powder. This should be allowed to sink into the skin for a few moments and finally the shoulders should be polished lightly with a clean leather …’. Surely they were confusing a lady’s toilette with the rubbing down of a horse!

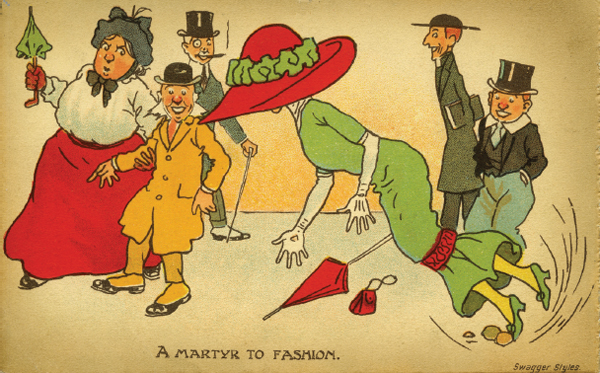

‘A Martyr to Fashion’ – a comic depiction of the hobble skirt. (Author’s collection)

It is not clear whether the large coiffures of the ladies gave rise to big hats or that big hats needed to be supported by ‘big’ hair. (Author’s collection)

Lady with parrot, a fashion plate from 1910s–20s. (Author’s collection)

With the slow but persistent growth of female emancipation and a changing lifestyle that would see the female skirt rise to knee level in 1926, fashion in 1910 would have one last attempt at reining women in and enveloping them in a restricting cocoon – the ‘hobble’ skirt. This phenomenon is sometimes credited to Paris designer Paul Poiret, who developed dresses on an oriental theme. Others attribute it to Mrs Hart O. Berg, who took an aeroplane flight with Wilbur Wright in 1908. During the flight she tied a rope around her skirt just below the knee to prevent it from blowing around, and failed to remove it immediately on landing causing her to hobble as she walked. In truth, it was more likely to simply be a natural extension of the longer, slimmer skirt that was coming into vogue. Unfortunately, to wear them properly a woman was required to tie a braid around the skirt just under the knees to prevent her from taking too long a stride and tearing the dress, or alternatively wear a loop around each leg underneath the skirt connected by an elasticised band. Many hobble skirts did in fact have slits or hidden pleats which helped a woman to move more freely, but even then it did not suit all woman and one newspaper commented this was because all female bodies were not ‘equally harmonious’.

Surprisingly, at first it was a sensation. At the Brook Manufacturing Company in Northampton 1,200 female workers went out on strike as they said there was such a demand for the skirt it could not be manufactured quickly enough, and having been taken off other jobs to concentrate on the ‘hobble’ they could not make a sufficient wage. Subsequently, the skirt did not last very long as normal, everyday things such as catching a train became difficult. Whenever a train was getting up steam to glide out of the station a stream of frantic girls in hobble skirts would endeavour to catch it, resulting in a marked rise in female unpunctuality at work as trains were often missed. It was banned in Paris due to the accidents it caused. Women fell so often and so awkwardly that arms and legs were broken. Mrs Ethel Hawksley Linley, aged 32, was walking in the country while wearing such a skirt and attempted to climb a stile, fell, broke her ankle and subsequently died in hospital of the shock. The demise of the skirt was commented on when the Evening Telegraph and Daily Post (Scotland) reported that the old clothes markets have ‘thousands of hobble skirts at knock down prices but there are no buyers!’.