Abominable Trousers and Rationed Fashion

‘Women in Trousers, a delightfully feminine regiment’

Worcester Journal, 1939

As early as 1876 women who sought greater emancipation and ventured to wear trousers were the subject of much condemnation and were said to be suffering a ‘curious disease that should be treated with the usual methods in use at the best conducted hospitals for the insane’, or so said the New York Times, 27 May 1876. By the end of the nineteenth century it was deemed acceptable that for ladies pursuing sports or gymnastics it was appropriate to ‘dress their legs in separate envelopes of cloth’. By 1911 ‘harem pants’, courtesy of French designer Paul Poiret, were trickling into high fashion and made the cover of Vogue magazine in 1913. The First World War also established trousers as a practical and less dangerous alternative to long skirts in the male-oriented workplace. Yet, the adoption by women of masculine fashions was not something that was confined to the twentieth century. As early as the 1600 women wore masculine riding jackets and broad-brimmed hats. Military styling on Regency Spencer jackets took the form of braiding and regimental buttons, and bloomers that appeared in the 1840s and 1850s were worn under knee-length skirts before the tailored skirt suits of the 1860s and 1870s which were modelled on masculine styles.

Trousers for women were really popularised by Chanel in the late 1920s as a leisure garment and cut to be quite baggy, the idea being that they hung in a similar way to a skirt. In the 1930s Hollywood actively promoted trouser wearing, with actresses like Katharine Hepburn and Marlene Dietrich wearing them both on and off the screen, not only singularly but as part of a suit. At first women’s trousers were quite ‘mannish’ made in masculine fabrics with deep turn-ups, and when coupled with a jacket and flat-heeled shoes definitely invoked a masculine outline. At one time this silhouette became so prevalent fashion writers cautioned their readers to approach long-haired ‘men’ in suits with caution, ‘since styles had reached the point where you slap your uncle on the shoulder and it turns out to be your aunt’.

Dresses were by no means side-lined, especially now that skirt lengths had fallen dramatically from the dizzy heights of the 1920s, adding to a new long, lean sophisticated look. Many forward-thinking women viewed trousers as an expression of a new-found confidence. One brave gentleman in 1932 made the statement that he thought the wearing of trousers by women was a symbol of their changed outlook and foreshadowed a time when women would be the superior sex and the dominant partner in human relationships. In hindsight that was nothing short of prophetic.

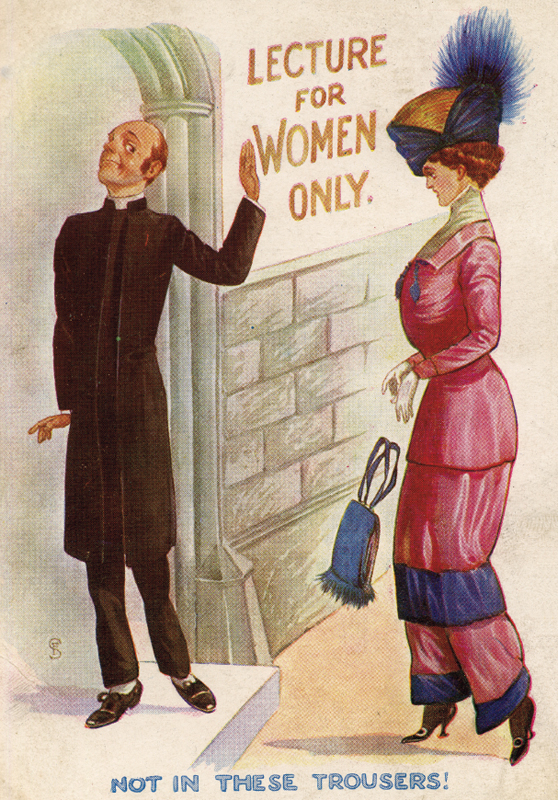

A 1918 political glamour statement from the Spurgin Women’s Suffrage Lecture. (Author’s collection)

The lean and slender lines of the 1930s. (Author’s collection)

‘The Lines that Slenderise’, Woman’s World, June 1931. (Author’s collection)

Being slender was the best way to wear trousers and women were encouraged to adhere to a weight restriction of under 150 pounds (68 kilos) if they wanted to look their best. Despite being favoured by many well-heeled and constantly dieting young women, now able to dress themselves effortlessly, outside Tinsel-Town trouser-wearing in public was far from socially acceptable. A most controversial subject, opinions, judgements and conflicting points of view unravelled almost daily across newspaper columns and the pages of fashion and lifestyle magazines. One such report appears drastic and quite sexist by today’s standards when in 1933 two nurses at the Leicester Royal Infirmary were dismissed for wearing men’s flannel trousers when off duty! Admittedly, they had been warned by the matron that it was not in keeping with the dignity of the profession or of the hospital. Both voiced their indignation that they should be thus penalised for following fashion when not even at work.

Reports of numbers of young women parading in what were clearly men’s ready-made flannel trousers was reported in the Liverpool Post, which commented that it was both ‘ungainly and vulgar’ and that they looked ‘horrid’. It comes across to the modern ear all the more shallow and petty when the article added that ‘Some men hold the opinion that a beautiful woman should still look beautiful whatever she wore; some of the modern young men however do not include trousers in this category.’

The idea held by the male half of the population that women in trousers had the propensity to be ‘troublesome’ was reiterated when in 1936 a master of Trinity College, Cambridge suggested wearing trousers and smoking cigarettes amounted to the same thing, namely a threat and abomination. Having noticed that the proportion of non-smokers to smokers had noticeably increased at the college in recent months, he put it down to ‘antagonism of the sexes’. In his words, since ‘copycat female undergraduates’ had taken up smoking and so ‘mimicked the superior sex’ the men at the university, afraid of appearing ‘as effeminate as to puff on cigarettes like mere women’, had given up. He then added that if the fashion for women to wear trousers ever extended to the college, men ‘in order to preserve the difference between the sexes will be driven to wearing kilts!’.

The 1930s’ movie star Marlene Dietrich in her ‘mannish’ suit. (Author’s collection)

The blatant dislike of women upsetting the natural order of things was obvious in an exchange in the Hull Daily Mail in 1936, when a Bradford girl defendant astonished the local magistrates by appearing before them wearing grey flannel trousers. She had been summoned for using a motor vehicle without appropriate insurance and when called forward was asked her name. ‘Mary’, she replied to which the judge, noting the trousers and short hair, quipped, ‘Are you sure?’

With Hollywood fronting the trouser trend it was only a matter of time before an interview with an American actress appeared in a British newspaper. A publication called the Citizen asked the legendary actress Marlene Dietrich, ‘the epitome of femininity on the screen’ among other things, why she liked to wear trousers considering all the controversy. She apparently defended wearing the ‘mannish’ fashion by saying she thought them both ‘warm and comfortable’; it was less expensive to look smart in trousers than in a gown and finished by saying that as she pleased film directors and producers by wearing frills and flounces on set, why should she not please herself once out of the public eye? Three fair points all of which sound perfectly rational!

With the advent of war in 1939 the controversy surrounding trousers temporarily shifted as they became – just as in 1914 – acceptable for women to wear for war work. In March 1941 Ernest Bevin, Minister for Labour, called on the women of Britain to help the war effort, and many not only took new jobs in the munitions factories, but also worked in tank and aircraft factories, drove trains and tractors and operated cranes. Extravagant clothing was ousted by trousers or dungarees and scarves tied around the head to stop hair becoming trapped in machinery. German air raids also made trousers for women a necessity at this time with the ‘siren suit’ considered the first real ‘fashion’ item of the war.

This all-in-one boiler suit style first originated in the First World War as practical clothing for munitions workers. The 1940s’ styles were usually hooded and had capacious pockets to hold as many objects as possible, given that time was of the essence when leaving your house in a raid. Similarly, they needed to be quick and easy to put on, over night clothes or pyjamas. It was also vital that they were practical to protect against the inhospitable environment of the air-raid shelter, which could have been either a dug-out (Anderson shelter) in the garden or a public shelter such as an Underground station. They were, by all accounts, probably the first and equally the most unlikely fashion garment of the war.

Yet it was not Britain’s first experience of ‘crisis’ clothes. The origins lay in a comparable disaster 200 years earlier when a series of earthquakes threatened to crush Georgian London from beneath just as air raids were about to obliterate the twentieth-century capital from above. Letters from Sir Horace Walpole written from March to April 1750 served to convey the phenomenon, stating that ‘within these three days seven hundred and thirty coaches have been counted fleeing past Hyde Park corner, from the alarming effects …’ and that with the possibility of further tremors London would have been swallowed up. Walpole advises there was little to be done, though one enterprising young man did sell pills which he claimed were very good against an earthquake, and when London was in the grip of a ‘shivering fit’ women donned ‘earthquake gowns’. Simply made and of functional fabrics, these were to protect themselves against the cold night air, mud and damp as they sheltered on the heights of Hampstead and other ‘safe country spots’ for fear of being trapped inside their houses should they have collapsed. With two earthquakes already having taken place in the preceding months the old superstition that things happened in threes abounded, just as it did in 1940 where people were trying to predict the exact date of an all-out German invasion. Even air-raid shelters were nothing new. Their equivalent had already been invented in the reign of James I, who, having a morbid fear of fog, ordered the erection of small buildings complete with seats and the facilities for a fire for those caught out in bad weather to take shelter.

The siren suit even had royal patronage as Princesses Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) and her sister Margaret both owned one, as did Winston Churchill who, preferring to call it his ‘romper suit’, caused a media stir when he wore his travelling from Boston to New York on war business.

Even when prompted by a global crisis, for some, women in trousers was still unthinkable. On 3 October 1939 the Dundee Courier reported how a Middlesbrough magistrate, as part of clarifying an item mentioned in his case, asked in court, ‘What is a woman’s Siren suit? Is it a suit that women wear after the siren has gone or a suit which makes them look like a siren?’ The resulting comment from his clerk, ‘It is just a woman’s excuse to wear trousers!’, was to the point, sexist and blatantly condescending.

Trousers, or the boiler suit, worn by munitions workers in the First World War re-appeared in the Second World War. (Author’s collection)

Trousers were worn for war work in both world wars. From WW1 Women at War – the Munitions Factory. (Author’s collection)

The practical ‘siren suit’ of the Second World War years. (Author’s collection)

The siren suit was a success and sold even after the immediate threat of air raids had passed. The store D.H. Evans marketed them as a practical and common-sense garment and advertised ‘a fashionable, wool, zip fronted siren suit, with belt, cuffs, hood and pockets all in cobalt blue for only forty five shillings and sixpence’. This wartime phenomenon did much to establish trousers for women, but they remained a gender specific garment in the eyes of men, with critics still considering it ‘improper to indicate the shape of a woman’s leg with trousers’. One editor of a women’s magazine aired her views by saying that she believed ‘trousers simply will not be around in the future as men do not like them’. In hindsight, a slight faux pas on her part?

In 1942, however, trade experts announced that more women would adopt trousers due to the shortage of suspenders, which was a direct result of a lack of rubber, which in turn was no longer allowed in the manufacture of girdles. Women were going bare-legged, even if stockings were available. In America women were asked to give up the stockings they did have by taking them to collection points displaying signs that read ‘Uncle Sam needs your silk or nylon stockings for gun-powder bags and parachutes’. They had already given up their girdles to save on rubber and now each parachute needed at least thirty-six pairs of stockings.

If a woman could not go completely bare-legged then, on both sides of the Atlantic she was encouraged to wear ankle socks instead. This was no mean feat as for centuries women’s legs had been covered and even as late as 1934, only five years before the war, it was commonly thought that ‘Few women possess limbs so perfect that they can be extravagant in the freedom afforded to legs …’, and that without stockings an ‘ensemble’ is not finished off, as reported in the Gloucestershire Echo, Wednesday, 16 May 1934. In short, wearing stockings made a woman well groomed and, according to the article, ‘assisted a woman to a sublime state of mind’.

When, in reality, it is doubtful that any women would de-stabilise the war effort simply to appease her state of mind, the lack of stockings was particularly hard to assimilate. In 1942, however, one newspaper was pleased to announce that at least one English county had an answer to the stocking problem. It appeared that ‘depots’ were shortly to open where women could take old stockings to be re-heeled and re-soled with salvaged materials which had been cleaned and sterilised. A wide range of shades was available in large quantities so it was possible to effect a suitable match. The charge for silk stockings would be 2 shillings and 6 pence. No coupons were needed for such mending. Fortunate for some. However, not to be thwarted by location, those women still wishing to appear well groomed and not living in the county in question turned to gravy browning and a good friend who could draw, with an eyebrow pencil, a good straight line as a stocking seam down the back of their leg. If all else failed, befriending a black marketer or a visiting GI could get you a regular supply.

One of the most unusual items affected by the war was women’s stockings. With an embargo on Japanese silk, nylon was promptly drafted to make parachutes. (Library of Congress)

On Whit Sunday, 1 June 1941 strict clothes rationing was introduced with the following announcement:

Rationing has been introduced not to deprive you of your real needs, but to make more certain that you get your share of the country’s goods – to get fair shares with everybody else. When the shops re-open you will be able to buy cloth, clothes, footwear and knitting wool only if you bring your food ration book with you. You will have a total of 66 coupons to last you a year; so go sparingly. You can buy where you like and when you like without registering.

This strategy was severe and took the population from being used to ‘plenty’ straight to ‘hard to come by’ and by pre-war standards such an allowance would have been spent in the first quarter of any year. By 1942 this allowance had dropped to forty-eight coupons. Each page of coupons was a different colour to stop people using up all their coupons at once. People were only allowed to use one colour at a time, with the government telling people when they could start using a new colour. The coupon system allowed people to buy one completely new set of clothes once a year. By 1945 clothing coupons were as low as thirty-six a year and inevitably a black market in coupons sprang up and vast numbers of books, about 700,000, were lost or stolen in the early stages of the scheme.

The Allocation of Clothing Coupons for Males, 1941

| Item of Clothing | Adult | Child |

| Pair of Socks or Stockings | 3 | 1 |

| Pair of Boots or Shoes | 7 | 3 |

| Nightshirt or Pair of Pyjamas | 8 | 6 |

| Raincoat or Overcoat | 16 | 11 |

| Waistcoat, or Pull-over, or Cardigan or Jersey | 5 | 3 |

| Trousers (other than Fustian or Corduroy) | 8 | 6 |

| Fustian or Corduroy Trousers | 5 | 5 |

| Shorts | 5 | 3 |

| Dressing Gown or Bathing Gown | 8 | 6 |

| Shirt, or Combinations – Woollen | 8 | 6 |

| Shirt, or Combinations – Other Materials | 5 | 4 |

The Allocation of Clothing Coupons for Females, 1941

| Item of Clothing | Adult | Child |

| Lined Mackintoshes or coats (over 28in long) | 14 | 11 |

| Jacket or Short Coat (under 28in long) | 11 | 8 |

| Dress or Gown or Frock – Woollen | 11 | 8 |

| Dress or Gown or Frock – Other Material | 7 | 5 |

| Blouse or Sports Shirt, or Cardigan, or Jumper | 5 | 3 |

| Skirt or Divided Skirt | 7 | 5 |

| Apron or Pinafore | 3 | 2 |

| Pyjamas | 8 | 6 |

| Nightdress | 6 | 5 |

| Pair of Stockings | 2 | 1 |

| Pair of Socks (ankle length) | 1 | 1 |

There were items that could be bought without coupons such as clothing and sundries for babies under 4 months old, as well as overalls, hats and caps, sewing thread, mending wools and silks and shoe and boot laces. Also exempt were braids, ribbons and other fabrics less than 3in in width, elastic, lace, braces, suspenders, garters, clogs and black-out dyed cloth. Coupons were not needed for second-hand articles. The scheme continued to issue coupons until 1949, with all forms of rationing ending in 1952.

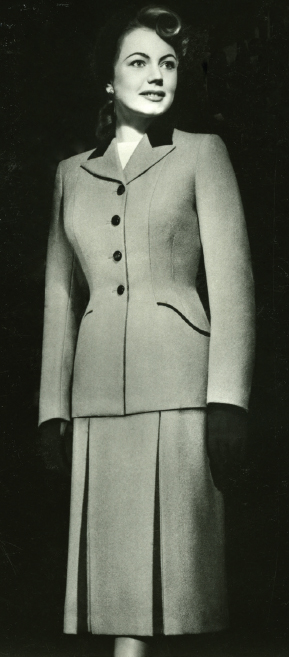

As well as the coupon system a utility or austerity scheme was introduced by the British Board of Trade, making sure that both low and medium quality consumer goods were produced at reasonable prices and to high standards, while also meeting the restrictions on raw materials and the freeing up of labour to work on more important considerations. This clothing carried the label CC41. Regulations affected the style and design of clothing and for women there was a limit on the number of pleats, buttonholes, pockets and seams items could have. There was a maximum width for sleeves, belts and collars. Seams themselves had to be narrow and hem length strictly regulated. Women were only allowed four buttons per coat. Men too had their extras cut. Shirts were much shorter in length, and no longer had double cuffs. Trousers had no turn-ups, jackets ceased to be double-breasted and pockets no longer had covering flaps. Such small things apparently, though insignificant, all added up. The 2in saved from the bottom of shirts and the changing of double to single cuffs on the sleeves saved 4 million square yards of cotton per year and freed up 1,000 workers from clothes factories enabling them to join the war effort. Similarly, embroidery, and special finishing in leather and fur trimmings, disappeared on outer wear altogether. All women were encouraged to polish up their sewing skills with easy dress and style templates produced in a number of limited but stylish designs. The female silhouette became refined and unadorned, her minimal but versatile wardrobe made up of short straight skirts and boxy jackets with shoulder pads. Yet in spite of its austere specification, utility clothing designs were commissioned from leading fashion designers including Hardy Amies, Norman Hartnell and other members of the Incorporated Society of London Fashion Designers.

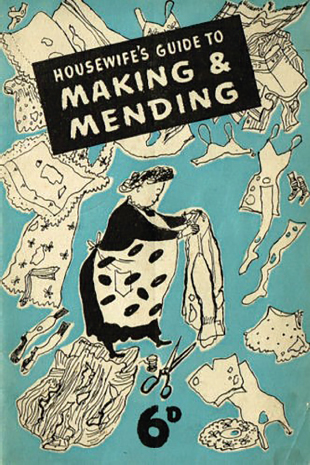

To tap into patriotism media campaigns were launched with a character named ‘Mrs Sew & Sew’ and the slogan ‘Make Do and Mend’ became a familiar mantra. The need to conserve every scrap of material in the country was of the utmost importance and universally discussed at council chamber meetings, which were charged with investigating ways of extending the scope of the ‘Make Do and Mend’ campaign. It was recognised that the voluntary services would be invaluable in providing information and in the provision of demonstrations. In addition, ‘Make Do and Mend’ centres, usually village halls, would employ a resident dressmaker to help with alterations and repairs. It was even proposed by some school superintendents that in order to take some of the burden off their mothers, pupils who were old enough should be allowed to bring clothes into school and carry out repairs themselves under supervision. Many schools also acted as clothes exchanges, where garments could be donated that did not require alteration.

Wartime utility fashion advertising card. Buttons and pockets were reduced in numbers as was the amount of fabric allowed to be used in making any garment. Utility Model No. 424 claimed to be ‘superbly tailored in fine, smooth, two-tone tweed’. (Author’s collection)

A 1940s wartime housewife’s guide to making and mending. (Author’s collection)

On 1 September 1943 The Times launched the Board of Trade’s booklet ‘Make Do and Mend’, which at a cost of 3 pence was a sound investment in the campaign to make clothes last longer in compliance with the war effort. The Times stressed that the booklet would ‘make rationing more tolerable’ as it contained practical hints, some no doubt already known to housewives but included many new ones necessitated by the circumstances. One section, ‘men’s clothes into women’s’, was especially mentioned, with the paper quoting, ‘Here are some ways in which a man’s unwanted garments can be converted to your own use …’, but stressed the woman should be ‘quite sure he won’t want them again after the war!’. It also had practical answers to the age-old moth problem that had blighted clothes from time immemorial.

Pillowcases were made into white shorts for summer, skirts were made from men’s old trousers and cast-offs expertly fashioned into children’s clothes. Collars would be added and trims applied all to eke out a limited wardrobe. Wedding dresses would be worn several times, borrowed by sisters and friends, until through necessity they had to be recycled into underwear or nightgowns. Blankets were used to make coats. The wedge shoe, first designed by Salvatore Ferragamo in 1936 from cork and wood, was practical, cheap and sturdy, lasting a long time and needing minimal repair.