Chapter V

The Master Abstractor and the Prime Minister

It was mid-May 1967 and David Phillips, the self-proclaimed Master Abstractor, had waited just about long enough. Dressed in a green tweed suit for which he’d had eight fittings, Master Phillips had just spent three horribly dull days stowed away in a paint locker aboard a Greek freighter bound for China. The freighter was loading grain at the Prince Rupert grain elevators, where railcar loads of Canada’s golden cargo had been hauled in from the Prairies. One can listen to the waterfall sound of grain being loaded for only so long and still retain some semblance of sanity. Disembarking in frustration, David had come to the decision that an aristocratic gentleman like himself should henceforth travel in style. Thirty years later, when he did finally get to China, he flew first class.

But these were leaner times, and David had to borrow $15 for a float plane flight to Masset. It was the closest to China he’d ever been since leaving his Toronto home and stowing away on the ship, and he was determined to get closer yet. He loaded a trunk with his tuxedo, fine English bone china, linen tablecloths, the best silverware settings, and cream-coloured gentleman’s gloves and set off from Masset harbour by rowboat into the setting sun. A salmon trawler in a deadly tide rip off Shag Rock rescued him. “I didn’t know what it was,” the Torontonian said of the tide rip. He was only fifty-six hundred nautical miles short of his goal and barely outside Old Massett village.

David settled into the Graham Island communities, fitting in well among other eccentrics and bringing his considerable culinary skills and distinguished taste to many local functions. It wasn’t until 1973 that the Master Abstractor, as he dubbed himself, ran into difficulties and notoriety.

David had been hired to lead a Canada Works program to clean up garbage along Graham Island’s newly completed highway. A two-plank elevated road just wide enough for one car at a time had been the historical transportation link between Skidegate and Masset. Now an all-weather sealed surface had suddenly brought the Islands into the twentieth century along with its associated consequences: speed, head-on collisions and highway litter. David was determined to deal with the latter. He cleared a ten-mile stretch of roadside by putting the trash directly in the centre of the highway: beer bottles, insulation, plastic bags, blown-out tires, whatever. “I’d look back occasionally and see a sea of garbage on the road,” David later commented proudly of his handiwork. Motorists and the RCMP saw things differently. There was already an Island-wide warrant for his arrest by the time he bunked down in Queen Charlotte City for the night.

Like Alice entering Wonderland, things became “curiouser and curiouser” for David the next morning. He found himself in Skidegate Landing sitting amid chopped-down cherry trees in full bloom. The small orchard was being cut down to make a playground for children. For David, suddenly every petal of every blossom became the crying face of an abused child. Many of the faces were Southeast Asian, David said. The Vietnam War was in its full napalm glory days so David deduced that the real problem was America, with its Southeast Asian arm of imperialism. He grew angry and looked for someone to help do something about the situation. On the right-hand side of the Skidegate Landing dock was a boat called Millionaire, and on the other side a boat called Survival. Through David’s eyes, the Millionaire boat embodied the USA, and the Survival boat was the Third World—and it was leaving dock. David stopped a passerby “as a witness before God” and declared war. He headed straight for Masset to inform the commanding officer of the Canadian Forces Station that World War III had begun. Halfway up-Island, it struck David that he wasn’t properly attired for such a historic undertaking, so he stopped in the little community of Port Clements at the head of Masset Inlet to get outfitted at a friend’s house as an officer. Now fully fitted with a captain’s hat and a double-breasted officer’s coat, he tore a picket from the Mayer farm fence, stuck it through an old car’s rusted-out headlight socket for a sword and charged north.

Captain David arrived in Masset with a sword of righteousness that could have rivalled Archangel Michael’s. He paused at his home a moment to collect himself and fill his pack with seashells and fine linen napkins so he could present himself properly. At the reviewing stand in front of the CFS Masset headquarters, he propped up his fence-picket lance and draped his cream-coloured cloth glove atop it “to let them know they were dealing with an officer and a gentleman.” He then proceeded directly to the base hospital and presented himself.

“I am Captain Master Abstractor David Lawrence Phillips, on loan to the United Nations,” he told the head nurse. “I report to you whole and uninjured; I have all my wits about me.” The nurse appeared dumbfounded as David continued. “I’ll be in the officer’s lounge. Would you please have your United Nations representative attend to me?”

The Canadian Forces Station in Masset in 1973 was no idle posting. This was still the height of the Cold War, and this base was the intelligence centre for a huge radar dish on North Beach that tracked and monitored all Soviet nuclear subs in the North Pacific. CFS Masset was a vital strategic link in America’s NORAD Distant Early Warning System, but something as simple as a request for the military base’s UN representative was enough to throw the whole system into disarray. As David himself said, “The military doesn’t work well when it doesn’t understand the line of command or the nature of the enemy.”

Captain Master Abstractor was pushing the system to the max. In the officer lounge, he wrote orders in the daybook dismissing all officers and reassigning them to the S’eegay—Masset’s notorious wino hangout. Captain Phillips then laid out his seashells and fine linens “to set the proper ambience and to feel at home.” Not receiving any response to his distinguished presence, he grabbed a phone and reamed out the top brass. “I’m not used to waiting around,” he growled. Shortly thereafter, a six-foot-eight-inch military police officer filled the doorway and asked David for his authority. The base had gone on Red Alert; the whole NORAD system may have gone on Red Alert. “They took me seriously,” David said.

With an uncanny comprehension of the military mind, Captain Master Abstractor adopted its fundamental teaching that the best defence is a good offence and confronted the imposing military police officer. “If you’re going to talk to me like that, I’m leaving,” David snapped convincingly. The burly MP quietly stepped aside while David gathered his seashells and fine linens and with an air of indignation marched out the door.

Word of the intrusion had now spread throughout the base, but some saw the developing drama less as a threat to “free world” security than as comic theatre. A dozen French Canadian solders sipping beer on a balcony applauded David as he paraded across the parking lot. “I felt like Montgomery coming out of North Africa,” David said later.

Walking toward the boundary between the Village of Masset and the CFS base, David now witnessed a civilian authority versus military authority standoff. An RCMP squad car came peeling out of police headquarters while a military police vehicle raced across the base, meeting bumper to bumper with the Mounties, who were, as always, determined to get their man. While the RCMP patrol car slowly pushed the military police car back to its proper side of the jurisdictional line, the ensuing standoff allowed David to quietly slip into the S’eegay pub and out the back door. But the noose of the law was closing in. The RCMP, still furious over the previous day’s highway obstructions, were in hot pursuit.

David was now fleeing the law in bare feet. It wasn’t part of any escape strategy; he’d simply forgotten where he left his shoes. He wandered over to Robin Brown’s house and then along the beach of Masset Inlet to Main Street, where he stopped to have tea with Clarence Martin, a respected senior in the community. Finishing tea, he borrowed $5 and went next door to Delmas Co-op to pay half his annual membership fee—paid to Co-op #165, Middle Hill Hatchery, David’s holding company. He walked out the front door into the waiting arms of the RCMP, who flew him to Prince Rupert for three days of “psych containment” and later sent him the bill for the services.

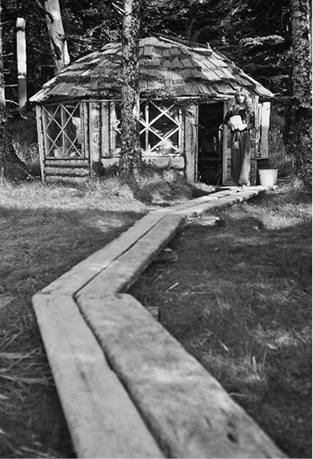

David Lawrence Phillips, Master Abstractor and master chef, welcomes guests to a typical beggar’s banquet at his Copper Beech House home featuring Haida Gwaii baked halibut, Dungeness crab and razor clam fritters.

The gallivanting days of Captain Master Abstractor had come to a sudden ignoble end, and David discovered for himself the consequences of stepping outside society’s definition of the straight and narrow. A doctor in Prince Rupert had David committed to an obligatory one-month term at Essondale mental institution in Coquitlam, BC. He was put on a tranquilizing therapy cocktail of six to nine drugs, then gradually withdrawn from them a few days at a time to measure his recovery from drug withdrawal. “It was psycho-pharmacology at its worst,” said David. “You have to be able to go into a psychotic state to give them an opportunity to analyze your madness so they can begin to program your wellness.” David short-circuited the system. He was told that within his institutionalized thirty-day term he would have to do a project to demonstrate his wellness. David loved projects. He organized everyone in his craft class to get dressed up in suits and dresses “like respectable people.” He called in the media and had all the inmates gather on the steps of the administration building with banners and placards to stage a protest against electroshock therapy.

A nearly brain-dead victim of this treatment was held up to the press as living evidence of the barbaric practice. The patients began a hunger strike in protest and David was shipped back to Masset, the town he forever after called “Essondale West,” well before his term of care was up. A dozen years later David ran for mayor of Masset and swept 25 per cent of the vote. In 1976, just three years after his romp with the CFS, the RCMP and Essondale Mental Institution, he found himself in charge of organizing the first visit in history to Haida Gwaii by a Canadian prime minister. He was, after all, a master abstractor.

Never one to mince words or gestures, Pierre Trudeau had created a bit of a stir in the early 1970s with his inference that there was no such thing as aboriginal title, and if there ever was, it was extinguished at the time of confederation. First Nations across Canada were in an uproar over the statement, and their wrath had the potential to unseat a few Liberals in key ridings. Paramount among these was the largely Indigenous riding of Skeena, which includes the Queen Charlotte Islands, and which happened to be the riding of the feisty Iona Campagnolo, the anointed president of the Liberal Party later destined to become the lieutenant-governor of British Columbia. Campagnolo had been trying for some time to get the prime minister into her riding to smooth ruffled feathers, but prime ministers from Quebec are usually as loath to cross the Rockies as are the eastern subspecies of the beaver. Trudeau himself would later show his love for the West by flipping the bird to his loyal subjects from the window of a touring railcar. That little gesture may have done more to fan the flames of a Western separatist movement than any political differences.

An invitation to address the United Nations Habitat Conference in Vancouver in 1976 offered Trudeau the global stage he loved so much, and it provided Campagnolo the opportunity she needed to stage an event in her riding. Masters of the staged public spectacle, the Liberals always know how to put together great events to meet their political agenda. Campagnolo was no slouch in this regard, and she conspired with her strategists to find the most suitable venue.

The Queen Charlotte Islands Museum Society had been working for decades to raise funds for a new building to showcase the Islands’ extraordinary natural and cultural heritage. The opening of the museum was now rushed to coincide with Trudeau’s visit to British Columbia.

David Lawrence Phillips, the Master Abstractor, just happened to find himself on the board of directors of the museum society at that fateful moment in history, and he spun his magic to further entice the Trudeaus to extend their visit to the Misty Isles. Engaging the talents of the QCI Artisans Guild, he created an intriguing and uniquely Islands invitation. A carved red cedar box was filled with Islands treasures: sand dollars and scallop shells, photos of alluring scenery, fresh cedar boughs, an argillite Haida carving and an anthology of Islands music. The box was strapped with a custom-made miniature crowbar and shipped to Iona Campagnolo, who personally escorted it to 24 Sussex Drive for a luncheon engagement with Margaret Trudeau. As she pried open the magic box, the Vancouver-born wife of the prime minister was instantly transported back to her West Coast homeland and the decision was made, then and there, to turn Pierre’s museum-opening function into a full family weekend.

The wheels began to turn quickly now. David frantically set up the itinerary and accommodations while Campagnolo’s office staff made inquiries of their own. Wouldn’t it be wonderful and politically astute, they reasoned, to have the prime minister meet with Indigenous leaders at the location of the first contact between Europeans and First Nations on the West Coast of Canada? The location, of course, would be Haida Gwaii, just offshore from the old village site of Kiusta. Here, in 1774, Spanish explorer Juan Perez accidentally came upon the archipelago when a storm blew his ship toward an unknown shore. Perez had been commissioned by the Spanish viceroy in San Blas, Mexico, to sail as far north as Sitka, Alaska, to lay claim to the entire Pacific coast before another Vitus Bering, or any other Russian expansionist, crowded in on these lands granted to Spain by the Pope. Perez’s voyage had been miserably rough and so blown off course that the crew had not spotted land north of Monterey, California. The northwestern extension of Haida Gwaii reaches out into the north Pacific like a great arm and catches all manner of flotsam, jetsam and lost European explorers. And so it was in July 1774, after more than twelve thousand years of continuous occupation by the Indigenous peoples, that Haida Gwaii was officially “discovered.”

Perez engaged with the Haida in some token trade, noted the latitudinal bearings in his ship’s journal and pulled anchor just as another North Pacific gale started brewing to blow him back down the coast. The intrepid explorer died at sea in 1775 on another northern journey. Two centuries later, the Liberals were looking for a somewhat different outcome.

“If the weather should force us to stay overnight at Kiusta, what’s the best accommodation available?” a spokesperson from Campagnolo’s Ottawa office asked the Massett Band Council by phone.

“That would be Huckleberry’s house,” they joked.

“Fine, book that,” came the response. It is not always easy for an Ottawa-based bureaucrat to realize that a site abandoned for more than a century and grown over in rainforest can still be listed as a place name on a map. Huckleberry House had to be one of those trendy titles for some new boutique hotel out there in Lotus Land, they must have assured themselves.

David Phillips sent word to me at Lepas Bay that the prime minister and his family would soon be joining me for dinner. It had to be a joke, I thought. While I carried on with my usual daily functions of gardening and clam digging, beachcombing, showering and laundering, the Islands’ communities were abuzz in preparation for the big day. Finishing touches were going on at the museum for the ribbon-cutting ceremony. The Canadian Forces Station soldiers were rehearsing their drills for a prime ministerial review and beefing up security to keep out any more Captain Master Abstractors. They needn’t have bothered, as they were simply a sideshow; David was already running the circus.

David had arranged for a small log house along the lovely Tlell River to be the Haida Gwaii version of 24 Sussex Drive for the Trudeaus’ visit. He borrowed the finest antique furnishings from all over the Islands to create the ambience of the pre-war era, a sort of understated elegance where imported English bone-china tea settings were laid out on fine Irish linen, and moon snails, beachcombed from the tide line, served as candy trays. Only a few staunch NDPers refused to loan their family heirlooms for the visit of the great rose-in-the-teeth Liberal.

The Trudeaus—Pierre, Margaret and their young boys Justin, Alexandre (Sacha) and Michel—were completely charmed and totally chilled by Tlell. They spent the evening and night hunkered down under a bed of comforters as David’s impeccably detailed preparations had left one item unattended: the propane heater didn’t work—a minor oversight.

The next day dawned gloomy but the Trudeaus were in good spirits, horseback riding and hiking through the lush, moss-draped countryside for which Tlell is legendary. After a delightful brunch they flew aboard a Ministry of Transport Sikorsky helicopter low over the east coast beaches of Naikoon Provincial Park, then north along Dixon Entrance to Masset. On landing in the ball field in front of CFS Masset, Trudeau performed his one official function, reviewing the troops and the equally regimented Boy Scouts and Girl Guides. Two dozen long-stemmed red roses were presented to Margaret before the official party was whisked off by car to Old Massett to meet the Haida chiefs and elders. The Sikorsky helicopter caught up with the party in the ball field beside the Ed Jones Haida Museum, and the entire entourage then headed twenty minutes west to the ancient village site of Kiusta for a tour of the archaeological dig and totem poles, escorted by Nick and Trisha Gessler and Haida summer students.

In May of 1976, after a tour of the surrounding area, the Trudeau family arrives at CFS Masset and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau disembarks the helicopter holding his seven-month-old son, Michel, while three-year-old Sacha (wearing a toque) chats with Justin, age five. Project Kiusta photo courtesy David Phillips

I’ve been told that I was named after the Apostle Thomas—“the doubting one,” my mom would often remind me—so the possibility of there being any truth to David’s message about the prime minister coming for dinner was almost nonexistent. Peter Norris, a good friend of mine with whom I had recently scaled the mountains called the Lions in North Vancouver and kayaked in Mexico’s Sea of Cortez, was visiting at the time and we had just finished hand-washing a week’s worth of dirty laundry, which we’d strung up in the cabin to dry as the weather was so foul. Having been cooped up much of the day, we put a pot of brown rice on the stove to slowly simmer and headed down the beach for a nice long walk. We were both dressed in ragged, throwaway clothes, having laundered everything better, and Peter actually had the entire crotch ripped out of the old shorts he wore. We were both joking about how embarrassing it would be if the prime minister actually did come when suddenly we heard the deep and unmistakable thump-thump-thump sound of a large helicopter’s rotary blades coming over the treetops. We could only start laughing; it was too absurd.

It was late in the day and the Trudeau family were already tired when they finished their tour of the ancient Kiusta Village site. David had promised the Haida students working at Project Kiusta a ride in the helicopter to Lepas Bay from where they could return by trail. I was told that after Pierre Trudeau looked at David and said wearily, “What next?” he heard Isabel Adams, one of the Haida archaeology students, plead, “Come on, David, you promised.”

David Phillips (with basket, centre) leads the “picnic on the beach” procession to Lepas Bay with MP Iona Campagnolo (far left), Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (in beret, centre left) and Haida students Billy Bedard (in toque, left) and Oliver Bell (foreground, right), who were working the Project Kiusta archaeology dig. Project Kiusta photo courtesy David Phillips

Far too many people disembarked from the MOT chopper that evening. The first view I had from the far end of the beach was the security detail running out to check the alder grove along the shore, either as a security measure or to relieve themselves—it was hard to decipher which from my vantage point. Next came the Master Abstractor and the prime minister in his trademark beret; both were laden with baskets of buns and raw Dungeness crab, garden salad and clam fritter batter. Iona Campagnolo emerged dressed in the de rigueur “Liberal red” and a gaggle of kids from Kiusta—Billy Bedard, Oliver Bell, Isabel Adams and others—filled out the procession along with Margaret, the Trudeau children and a small press corps.

One look inside the rustic driftwood cabin with wet, dripping clothes hanging everywhere was enough to tell even a Miss Manners detractor that nobody was expecting company. Pierre Trudeau was walking back down the beach toward me as I approached the cabin site. “I’m terribly sorry we’ve barged in on you like this,” he apologized while offering his hand in greeting. “Obviously we weren’t expected.”

“It’s no big deal,” I assured him nonchalantly. “People drop in unexpectedly all the time.” A warm smile came over the prime minister’s face. He adjusted his beret and accompanied Peter and me back to the cabin. We chatted aimlessly as we went. Was this a botch-up by his handlers? A public moment with no official expectations? A comedy of errors in an overscripted play? Trudeau seemed to love it, and when I offered to take him on a short hike to Lookout Point, one of my favourite places, he enthusiastically agreed.

The security service and press corps tried to follow. “I’d prefer not to have this place sensationalized in the press,” I said, and Trudeau caught my sentiment.

“We’d like to walk alone,” he told his entourage and the seas slowly parted. A few bodyguards looked concerned, but the prime minister reassured them with the words, “I’ll be fine. We’ll be back shortly.”

I’d never seen Lepas Bay so dreary. The sky was overcast and darkening, the tide was well out and the great expanse of normally glistening white sand was covered in the putrefying sludge of rotting seaweed. For Trudeau, however, this was paradise. “What’s the name of this island here?” he asked of the inner island connected to the beach at low tide.

“No name,” I replied.

“How about the island farther out?”

“No name also,” I said. Trudeau couldn’t imagine a place so wild that the most prominent geographic features were still nameless. “Do you think they should be named after prime ministers?” I chided.

He laughed. “Most certainly not.”

As we worked our way out over large, slippery beach boulders, I couldn’t help but admire this very personable, unpretentious man who just happened to be a head of state, despite my issues with some of his policies. I liked him from the start for two very down-to-earth stands of his early administration: “There’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation” and his ban on pay toilets. Like most Canadians who either loved his style and politics or took deep offence to one or both, I too had disdain for him invoking the War Measures Act nationwide for the kidnapping in Quebec of a British diplomat and the Quebec labour minister. I was also deeply troubled about the increase in oil-tanker traffic by Alaska supertankers along Canada’s Pacific coast, and I couldn’t understand why the federal government allowed US single-hulled tankers the right to pass through Canadian waters.

A satellite view of Lepas Bay shows the cabin location and Lookout Point where I took the prime minister for a private chat. MP Iona Campagnolo later referred to our talk as the “Supertanker Summit.” Google Earth photo

These troubling thoughts were going through my head as we climbed the steep, rocky promontory I had come to know as Lookout Point. “Let me help you,” I said, reaching down to Trudeau for the last slippery step before the summit. I pulled him up with one strong jerk and stood there holding his hand firmly as he teetered on the brink of an eighty-foot vertical drop. He looked startled, as if he suddenly understood why security should always be by his side. “Pretty scary, eh?” I said as we gazed down at the huge Pacific breakers exploding on the granite headland below us.

“Stunning!” he replied. “Absolutely stunning!”

Kaindus Koon, the Haida name for Cape Knox, stretched out before us, a spectacular array of high cliffs and lush hanging gardens of coastal vegetation. A Peale’s peregrine falcon swept down from its aerie and a bald eagle cried in defiance at our proximity to an eagle’s nest where she was incubating her eggs. To the south, the Haida’s legendary Tidalang Kun (Newcombe Hill) rose 152 metres above the shoreline and we could see all the way to Lavendar Point.

“That hill to the south is the basalt plug of an ancient eroded volcano,” I pointed out. “It’s incredible to realize how long this coast has been here, a rare ice-free refugium during the Pleistocene. Life has carried on here uninterrupted longer than almost anywhere else in Canada.” My talk was, of course, leading up to the subject of federal regulations on supertankers and the need to protect areas like South Moresby. I was wearing my Islands Protection Society cap in a symbolic sense, and the prime minister was now well aware that he was being lobbied.

We sat chatting together on that narrow promontory for a long time before we realized it was growing dark. “I know a shortcut back through the forest,” I offered, and Trudeau followed. We were halfway back to the cabin, walking along a deer path through the lush coastal rainforest, when a bird sang a perfect single note. “What a lovely song,” my guest exclaimed, “What bird is that?”

“It’s a varied thrush,” I answered. “Sit down for a minute and you’ll hear it call again.” We sat on a fallen log twenty centimetres deep in damp, luxurious moss. All around us was a fairyland forest of moss and lichen and massive trees in a million shades of green. The thrush sang again, in a different note.

“Lovely,” he said again as he rose to leave.

“The full range of notes takes five to ten minutes to complete and repeat. Wait awhile,” I encouraged the country’s busiest man. Neither of us spoke after that; we just sat and listened and listened and listened. The bird’s song spoke to the soul, it poured over us like sunshine pours into trees. It seemed nearly dark when we returned to chaos at the cabin. The Sikorsky helicopter had departed for Langara Light Station because they couldn’t get radio contact from Lepas Bay. The security agents were alerting Ottawa that the prime minister of Canada was missing on the westernmost extension of the Canadian coast and was last seen with a questionable-looking character named Huckleberry.

The cabin scene was a madhouse: packed with press corps, security men and Project Kiusta kids. Iona Campagnolo was pressed in beside the glowing-red barrel stove frying clam fritters. Her face was flushed the same ruby red as her clothing and she appeared more a character out of Dante’s Inferno than the cool leader of the Liberal Party that she was. Trudeau observed the chaos with the calm of a war correspondent. He said quietly to anyone willing to listen, “I wish you could have shared that moment with us in the forest.”

Ready for the prime minister and American ambassador … “Huckleberry House” on Lepas Bay opens its hobbit-sized door to the world. Richard Krieger photo

No one was listening. Everyone was too preoccupied with their personal needs: hunger, warmth and a dry place to hang out until the helicopter returned to rescue them. David, the mastermind behind the “picnic on the beach,” was trying to feed the masses in an octagonal driftwood cabin only three metres in diameter. “It’s a good thing you had a pot of rice on,” he said to me later. Maggie Trudeau was a true sport, sitting out in the drizzle on the beach and trying to get a hot enough fire going with wet driftwood to boil the Dungeness crab. My friend Peter was helping her with the fire tending. She joked about the very relaxed, hang-loose ambience of the scene, but kept sending her young sons, Justin and Sacha, to be with their father while she cuddled baby Michel. Suddenly Peter remembered that the shorts he was wearing had a ripped-out crotch seam, and scurried off, totally embarrassed, in search of safety pins.

The guests were all laughing and cracking crab when the Sikorsky returned. Suddenly everything seemed official again. “Gotta go now,” security beckoned authoritatively as the entourage boarded the helicopter.

“Nice bouquet,” I said to Margaret as she boarded beside the two dozen roses she’d received earlier in the day from CFS Masset. “Looks like a funeral arrangement,” I quipped.

“Oh, do you like it?” she teased back and started tossing roses out the doorway one by one as the helicopter lifted off. My last sight of Pierre and Maggie Trudeau was seeing them wave through a whirl of swirling sand and red roses falling from the heavens. It was somehow a fitting departure for a prime minister who captivated the world with a rose held between his lips and a wife who would soon leave him because she wanted to be “more than a rose in my husband’s lapel.”

I went back to my quiet, solitary summer on Lepas Bay, but the visit had made waves in Ottawa. My parents in Michigan and I both received letters from Pierre Trudeau saying how much he enjoyed his visit. Iona Campagnolo wrote to say that she had a long and frank discussion with the prime minister about US oil-tanker traffic following what she called our “Supertanker Summit” at Lookout Point. Not only did Pierre Trudeau ban tanker traffic through all coastal waters north of Vancouver Island, he went on to expand the ban to include all offshore oil and gas activity. Decades later, when his oldest son Justin became prime minister, he too pledged to put Dixon Entrance, Hecate Strait and Queen Charlotte Sound off limits to tanker traffic.

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau sent this personal letter to me shortly after his visit to Lepas Bay in May of 1976. The handwritten note says “P.S. I received a nice letter from your parents a few weeks ago. I was very glad to know them, as I was to know you.”

It was apparently at a formal diplomatic function in Ottawa in 1976 that the Trudeaus encouraged Thomas Enders, United States ambassador to Canada, to book a stay at Huckleberry House. And so it was, the following summer, that the Master Abstractor was called on again to spin his uniquely absurd magic and put together another high-level tour.

Thomas Enders was no lightweight American diplomat sent off to the north woods in Canada. He was a hard-core Nixon administration man who had played a forceful hand in America’s illegal and undeclared war in Indochina. These were critical times in US–Canadian relations, with threats of Arab oil embargoes and the security issues surrounding moving Alaskan crude through Canadian waters. Enders was the man the Nixon administration could count on to get the job done. Why the prime minister of Canada felt that Enders needed a three-day stay at Huckleberry House, the hippie shack of an American war objector, was anyone’s guess, but Trudeau was noted for his pranks and sense of humour.

The official delegation was made up of five people: US Ambassador Thomas Enders and his wife Gaetana; Hobart Luppi, consul general of the Unites States in Vancouver; Ghindigin, interpreter and host for the Haida Nation; and David Lawrence Phillips, Master Abstractor, impresario and other self-proclaimed titles. The RCMP were just about the last to know what was going on, and when they found out, they tried to stop it.

I had hiked over the Kiusta trail one afternoon to dig littleneck clams for dinner when I could have sworn I heard a float plane land on Lepas Bay. I returned at once but there was no sign of any aircraft. Footprints led up from the waterline of the rising tide to my cabin and back down to the beach. It remained a mystery to me until the Enderses eventually arrived and explained how the US embassy had received an emergency message from RCMP security: “Huckleberry House is a hippie shack unfit for human occupation.” The RCMP had used taxpayers’ money for that little gem of intelligence while the Enderses, once they arrived, proclaimed my cabin to be “one of the most charming places” they’d ever stayed at in the world.

It was June 1977 when the high-level diplomatic mission arrived on Lepas Bay via the Kiusta trail. The tide was high when the dignitaries arrived, so it was well after dark before they could get around the cliff at low tide to reach my cabin. Ghindigin helped ease the hours of waiting with a beach fire and a gallon of cheap Calona red wine. He slung it over one shoulder to take a swig then passed it to the American ambassador, a wine connoisseur who had a private cellar of some of the world’s finest vintages. Thomas declined, but his petite and sophisticated wife, who wafted the scent of a fine Italian perfume, took the bottle and a good guzzle without wiping the rim. Ghindigin was impressed, and he and Gaetana became instant soulmates, kicking back most of the gallon before the tide dropped.

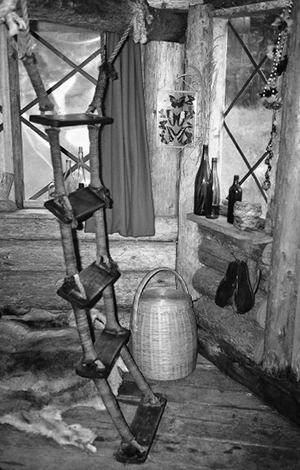

Consul General Hobart Luppi arrived on crutches and struggled over the kilometre-long trail through the forest and down the long, sandy beach with the determination of a soldier storming Normandy. He was given a fishnet and driftwood cot on the main floor to bunk down on once the party reached the cabin for the night. The Enderses had the honour of the half-loft directly above him. The loft could only be reached by negotiating the wobbly teakwood and rope ship’s ladder that had washed in from a Chinese junk. Beside the double foam pad that was to be the Enderses’ deluxe suite for two nights, I had placed a slab of driftwood as an end table. It was adorned with a glass kerosene lamp, a small vase of wildflowers and two purple olive snail shells in a simulated mating position. Ghindigin and I retired to tents to give the foreign diplomats the privacy of the cabin. We could hear them laughing all night at the utter absurdity of their predicament. Pierre Trudeau must have been having some chuckles back in Ottawa himself knowing where the Enderses were spending two nights.

The day I finished building a sleeping loft in my Lepas Bay cabin I was amazed to find a teakwood and rope ladder from a Chinese junk washed in on the beach with just enough rungs to reach the loft. Richard Krieger photo

Thomas Enders was an imposing man, a six-foot-ten Connecticut Yankee who could have played for the NBA rather than the Nixon and Reagan teams. He carried a large black briefcase that he never let out of his sight. Ghindigin suspected it might be a concealed automatic weapon. We never asked him what was in the bag, but he appeared to guard it with his life. One day he nearly fell from a steep ridge we were climbing to get to the north shore of Cape Knox, but even as he was struggling for a handhold he wouldn’t let me assist him by taking that black bag. He spoke of security and seemed to feel vulnerable with us—Ghindigin, David and me—with no bodyguard at his side. I told him that security for me was knowing where to get abalone, octopus and clams and which wild plants to eat. “That’s interesting,” Enders responded. “For me security is turning the switch to start my car and feeling relieved I haven’t triggered my own bomb.” I felt sorry for him after that.

Ghindigin has a disarming way with words. We were all sitting around one evening enjoying one of David’s masterful clam fritter concoctions when Ghindigin blurted out in his matter-of-fact style, “Well, I guess America’s on its way downhill now.”

Enders—the blunt-spoken conservative graduate from Harvard and Yale, nearly choked on his dinner. “What do you mean by that?” he challenged. Ghindigin cited America’s loss of the Vietnam War, the relinquishing of economic power to Japan and Germany, and inner-city decay. Enders wanted none of it; he was dipped and dyed red, white and blue.

We ate as much food from the sea as we could muster and never missed an opportunity to raise the issue of US oil-tanker traffic. The new proposal to make Kitimat a superport for Alaskan and overseas crude was still in the works, and Thomas Enders was the highest-level American ear we were going to find in Canada. There was method to our madness, and the Enderses’ departure from Lepas Bay on day three made us seem like moderates compared to the heavy lobby they got from Greenpeace’s flagship the Rainbow Warrior that had arranged to transport the US delegation from Kiusta to Masset. Waiting at the dock in Masset was Wilfred Penker, an Austrian immigrant to the Islands who carved huge, bizarre cedar masks. Wilfred was part of a guerrilla theatre skit depicting sea creatures dying in a massive oil spill. Gaetana was truly frightened by the episode, while Thomas clutched his black bag tighter than ever. It was all spontaneous theatre, though it must have appeared well orchestrated to the Enderses and a strange foreshadowing of things yet to come—the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska.

I never saw the Enderses after their three-day visit, though I did receive thank-you letters and Christmas cards for several years after. Ghindigin and his sons Gwaai and Jaalen, along with his spouse Jenny Nelson, had a pleasant dinner at the US embassy with the Enderses during an Ottawa visit.

For me, on Lepas Bay, the visit was another phantom experience. Like Margaret Trudeau’s roses wafting down from the sky, Gaetana’s fine Italian perfume masked the usually smelly outhouse for days after she left. These were strange times when unlikely lives crossed paths and reverberations of those passing connections were felt for years to come.

The Trudeau visit had created a conflict for me with a person I didn’t even know. Dorothy Richardson, the matriarch of Tlell’s oldest homesteading family, was outraged that a Liberal prime minister would shun lifelong Islanders and Liberals to dine with “some immigrant hippie on the West Coast.” She had every right to feel slighted; I didn’t blame her.

Some months after the Trudeau visit I knocked on her door. “Are you Dorothy Richardson?” I asked politely.

“Why, yes,” she said, surprised.

“Hi. I’m Huckleberry and I hear there are some hard feelings.”

“Please come in, dear, and have some tea and cookies,” she said warmly, but was obviously taken aback by my approach. We never touched on the sensitive subject then or any time after.

Not long after their visit, Maggie Trudeau was grabbing more international headlines than her husband. Tired of playing second fiddle as the obedient wife of the prime minister, she started acting her almost-twenty-nine-years-younger age in trendy hot spots, hobnobbing with the likes of Mick Jagger at Studio 54 in New York.

I recall a six-month winter sojourn I made to South America where I always received the same response to friendly chit-chat that began with “Where do you come from?”

“I come from Canada,” I would reply. Even answering the question in Spanish didn’t calm the ensuing confusion over the word Canada, followed by a pleased look of comprehension. “Ah, Canada, entiendo (I understand)—Maggie Trudeau and Mick Jagger!”

The last word about the Trudeau visit didn’t reach me until twenty years later when I happened upon the Redheads, the light-station keepers at Race Rocks, just outside Victoria. They had been the lightkeepers at Langara Light Station during the time of the Trudeaus’ visit and had been drawn into the drama of Huckleberry and the missing prime minister when the PM’s helicopter flew to their station to notify Ottawa that the prime minister was missing. They were delighted to see me again, and Mrs. Redhead even knitted me a bold black-and-white-striped watch cap with a red-top tassel—just like the painting on the Race Rocks light tower.

“Do you recall telling the prime minister that MOT helicopters were disturbing the falcons at Lepas Bay when they logged training hours?” she asked me.

“Yes—but how could you have known that?”

“Well, shortly after Trudeau’s visit to your cabin we received a memo sent out nationwide,” she said. She told me it read:

By order of the Office of the Prime Minister, all MOT helicopters are barred from any unwarranted landings on Lepas Bay. Huckleberry believes it disturbs the falcons, and it most certainly disturbs Huckleberry.

—Pierre Elliot Trudeau,

Prime Minister of Canada