Chapter VII

Islands at the Edge

By the late 1970s several Canadian luminaries and internationally renowned figures had begun lending their support to the Moresby cause. Among them were celebrated artists like Bill Reid, Robert Bateman and Toni Onley, national broadcaster and geneticist David Suzuki, internationally acclaimed undersea explorer Jacques Cousteau, as well as royalty like Prince Philip and Prince Charles. As one might expect, Bill Reid, of Haida ancestry on his mother’s side, was one of the first celebrities to do so.

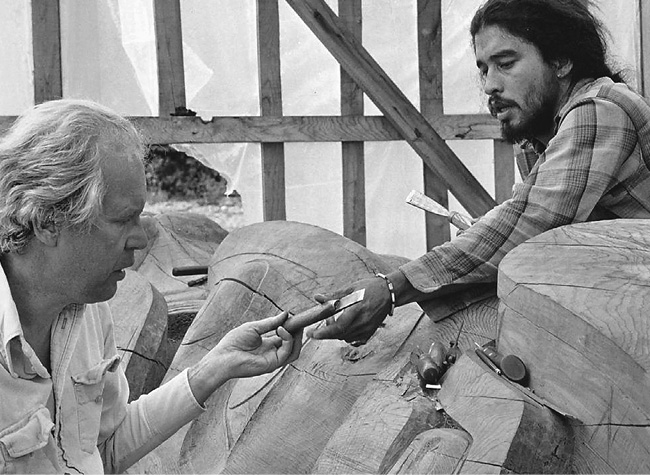

My first encounter with the master carver came in the summer of 1976 one morning at dawn after I’d spent a night curled up beneath the dogfish pole Bill had been commissioned to carve for the front of the Skidegate Band office. Ghindigin was assisting Bill with the carving, and he wanted me to meet Bill to help persuade him to support our cause. By the time I hitchhiked down from Masset to Skidegate Landing where the pole was being carved, Bill had already put down his tools and gone home for the day. Ghindigin suggested I sleep under the pole in a bed of cedar shavings to get a better feeling for their creation and to be in position to meet the esteemed artist first thing in the morning.

I have no idea what Bill thought of me as I emerged somewhat groggily from beneath the pole, my wool shirt covered in shavings, to greet him when he arrived at work that morning. He struck me as a man of few words as he went about his business, seemingly uninterested in what Ghin and I had to say. Supernatural beings were slowly being released from the fine-grained confinement of centuries-old cedar, and Bill seemed silent almost out of reverence as he chipped away at the great log. Ghin and I did our best to persuade him to back the Moresby cause, but at the end of the day he left us with a single thought: “The way I see it, boys, is you’re going to be living together on these islands with those you oppose for a long time to come.”

The dogfish pole carved by Bill Reid and Guujaaw stands proudly in front of Skidegate’s longhouse.

It was true, we would be, and there was certainly wisdom in his words. With only five thousand Islands residents at the time, everyone pretty well knew everyone else’s business on Haida Gwaii, especially when it was none of their own. The Islands’ grapevine was faster than a superconductor, and we had to be careful to not alienate potential supporters. Still, Bill must surely have heard what we had to say—he was reminded of it day after day as I continued to meet with Ghindigin at the carving shed to discuss strategies.

The scourge of Parkinson’s disease, diagnosed six years earlier, was slowly taking its toll on Bill’s body. It is hard to imagine a worse fate to befall a master carver, designer and goldsmith than to lose control of motor functions in the hands. Ghin once told me that he was carving on the pole one day and encouraging Bill to let him carve voluptuous breasts on a female figure. Bill, who was having an especially bad day with Parkinson’s, would not consent. After fumbling hopelessly with his carving tools, he finally set them down in disgust. “You keep carving, Ghindigin,” he said as he headed off for home. “I’m feeling about as useless as a tit on a totem pole.” In the end, Bill Reid’s contribution to elevating Rediscovery and the South Moresby cause was anything but useless, for once he was on board with us he threw the full power of his esteemed position behind our initiatives and donated prints and artwork to help fund the efforts.

There were so many important events in the years leading up to the Lyell Island blockade that it is difficult to recount them all. The All-Island Symposium in 1980 certainly set the stage for bringing Queen Charlotte Islanders on board. Using the stunning images of professional photographers Richard Krieger and Jack Litrell, and with a musical score produced by artist Lark Clark, a slide presentation on South Moresby’s world-class features wowed the crowd at the Queen Charlotte Islands’ new museum. Even the logging industry spokesman at the conference commented, “The Islands Protection Society does a consistently fine job of presenting their bias.”

In 1977, earlier in the campaign, to help ease tensions, Paul George and Richard Krieger suggested that I make a trip to the logging community in Powrivco Bay that would be shut down if our wilderness proposal met with success. Having worked a short stint as a logger myself, and being a firm believer in the power of dialogue to diffuse differences, I took Paul and Richard up on it.

We first presented a slideshow with Richard’s images showing the values at stake and the impacts logging can have on ancient forest-nesting seabirds like auklets and murrelets. We spoke of the impacts of increased sedimentation from road building on salmon streams and intertidal life, and we expressed alarm at the soil mass wasting from landslides triggered by logging steep slopes on islands with high seismic activity and heavy rainfall. It all might have fallen on deaf ears, because the first question that came up after my presentation was “Do you have some kind of a hard-on for IT&T?” International Telephone & Telegraph, give or take a name change, was the multi-billion-dollar corporate owner of Rayonier (B.C.) Ltd. at the time, though that was the first time I was made aware of it.

Bill Reid and apprentice carver Guujaaw work on the dogfish pole in a makeshift carving shed in Skidegate. Richard Krieger photo

In 1983, John Broadhead shared my vision of producing a publication that would elevate the Moresby campaign to the national and international level. We had already collaborated successfully on the production of All Alone Stone, a magazine for the local communities, and we were bold enough to think we could now produce something much bigger—a book! We quickly put together a prospectus and began soliciting experts in various fields to write specific chapters. Bill Reid agreed to write the compelling opening chapter, “These Shining Islands,” and his French wife Martine, while in Paris, managed to solicit a foreword by none other than the world’s most celebrated undersea explorer and co-inventor of the self-contained underwater breathing apparatus (SCUBA)—Jacques Cousteau.

John and I wrote several chapters of the book and enlisted the professional help of Bristol Foster, director of the BC Ecological Reserves program, to write a chapter on Queen Charlotte Islands endemic species. Jim Pojar, a professional forester, wrote a chapter on the ecology of ancient forests, David Denning of the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre wrote a chapter on marine life and Wayne Campbell, an ornithologist at the Royal BC Museum, composed the chapter on seabirds. It all looked pretty impressive, but we had no publisher.

Paul George, Guujaaw and I pose for a photo during a reconnaissance trip to South Moresby in the early days of the struggle to protect Hdaida Gwaii from clear-cut logging. richard krieger photo

Co-authors and designers John Broadhead and I present a copy of our book, Islands at the Edge, to Prince Philip.

It was Bill Reid who opened the door to this unorthodox publication being considered by Western Canada’s largest publishing house at the time, Douglas & McIntyre. Bill had been publishing most of his works through this house, and he suggested he might go elsewhere if the owner, Scott McIntyre, didn’t meet with me and John to review our manuscript. We met with Scott at his Vancouver office, but much as we tried to persuade him of the growing support and potential audience for this book, he remained reluctant to buy in. “I have a whole warehouse full of my optimism,” he told us. Further lobbying on the part of Bill Reid finally persuaded Scott to take it on. Because we were in a rush to publish and all of Douglas & McIntyre’s book designers were tied up with other projects, Scott reluctantly agreed to let John Broadhead and I design the book. JB’s artistic skills seamlessly wove together both images and artwork donated by several acclaimed Canadian artists. The style was unorthodox but bold enough to set a new trend in BC publishing. Islands at the Edge: Preserving the Queen Charlotte Islands Wilderness became an instant, award-winning success. Alan Twigg at BC BookWorld had this to say about it:

The turning point for recognition of Haida Gwaii as a separate culture—the book that, more than any other, made it acceptable and even preferable to refer to the place as Haida Gwaii—was Islands at the Edge: Preserving the Queen Charlotte Islands Wilderness (1984), a co-operative project largely engineered and written by Thom Henley. Later renamed Islands at the Edge: Preserving the Queen Charlotte Archipelago, this political milestone was accorded the first Bill Duthie Booksellers’ Choice Award in 1985.

At the gala event on Granville Island, Henley asked artist Bill Reid to give an acceptance speech. Reid’s riveting denunciation of modern BC society was not only the highlight of an evening that marked the coming of age of BC writing and publishing with the creation of the BC Book Prizes, it signalled to the mainland that Haida culture would henceforth aggressively seek self-definition. Quivering with Parkinson’s disease, Reid reminded the audience of the ravages of white civilization, calling it “the worst plague of locusts.”

Islands at the Edge was a powerful ambassadorial force in the successful preservation of South Moresby Island as a park. Its success begat a string of well-researched coffee table books to protect the environment, notably Stein: The Way of the River (1988) by Michael M’Gonigle and Wendy Wickwire, and Carmanah: Artistic Visions of an Ancient Rainforest (1989), spearheaded by Paul George, who had produced a similar book about Meares Island in 1985.

The person who paved the way for the success of our book and created a national customer base was none other than Dr. David Suzuki. The Nature of Things documentary on Windy Bay that aired nationwide on January 27, 1982, had already made South Moresby a household name three years before the book was released.

I, like millions of Canadians, Americans and Australians, was a huge fan of Suzuki’s courageous, pull-no-punches broadcast style. From a little-known geneticist at UBC to one of the most respected men in the country, his ascent arose from his humble but passionate commitment to protecting the planet and human rights. It was a great honour for me to be invited aboard his helicopter in the autumn of 1981 and fly down to Windy Bay to complete a shoot for an upcoming Nature of Things program. David’s film crew had been stormbound in Windy Bay for several days prior to our arrival, and it was clear from a falling barometer and darkening sky that another autumn gale was fast approaching.

“David, you don’t have time to go into the forest. We’ve got to get this shot and leave ahead of the storm,” a member of Suzuki’s crew told him as we disembarked on the beach and ran out under the swirling rotary blades of the helicopter to the forest edge. “This is the most spectacular forest we’ve seen anywhere in the world,” his crew member added. “You’ve got to tell people that, David.”

David Suzuki, renowned geneticist, broadcaster and conservationist, gave the Moresby campaign a huge boost when his The Nature of Things show featured the area’s natural wonders. According to Suzuki, this episode got more letters and calls than any other show he’s ever done. Jeffrey Gibbs photo

I have never before seen such a level of professionalism as when David very calmly sat down on a beach log that day, looked straight into the camera and delivered an eloquent and heartfelt testimonial. I was filmed for the show, as was Ghindigin, who was now called Guujaaw. David later took on a devil’s advocate role with Guujaaw, asking him why saving the area was so important to the Haida. Guujaaw had spoken of how the Haida’s whole cultural and spiritual identity was tied to the land. “So what are you trying to tell me?” Suzuki challenged. “Will you no longer be Haida if they log these islands?”

Guujaaw confessed to me later that he was a bit stumped for a reply, so he just answered, “Nope, we’ll still be here. We’ll just be a bit more like everyone else.”

That reply, David Suzuki told me later over dinner at his house, totally floored him. My God, he thought, these people really see themselves as different. It was the seminal moment that moved him into an entirely new direction in his life—becoming a champion for Indigenous people’s rights worldwide. But Suzuki wasn’t popular everywhere, and he came under increasing threats from the logging community in Sandspit following the Windy Bay broadcast.

What really set the Moresby cause apart from all others and started a new national trend was the close alliance that was forged between the Haida in asserting their rights and a conservation community placing their bets that Haida stewardship would easily trump the BC government and federal agencies in protecting the area. The bet paid off.

Bill Reid and David Suzuki were guest speakers at a Vancouver rally for South Moresby. Jeffrey Gibbs photo

There is an ancient name for Haida Gwaii that translates roughly as “Islands Emerging from (Supernatural) Concealment,” reflecting the mythical origins of the Haida archipelago. Scientists have their own myth based on tectonic plate movements. The Haida Islands are considered geological gypsies, cast adrift aboard a plate that has been slowly shifting northwestward from an area that is now Baja, Mexico.

Now perched on the very edge of the continental shelf and pressed against the howling gales of the Pacific, the 150 islands that make up the archipelago are said to have the highest-energy coastline in all of Canada—a scientific analysis based on factors such as wind speed and wave action. We knew all of this, of course, when we titled our book Islands at the Edge and intended the double meaning with the logging threats to South Moresby, but no one at the time recognized our movement was on the edge of effecting change on a global scale.