Chapter XI

Wave Eater

One final act had to be performed before the curtain came down on the South Moresby show, but the actors were unaware at the time that they were even being cast for it. Bill Reid had been commissioned by the Bank of British Columbia to carve a twenty-four-metre traditional Haida canoe for Expo 86 in Vancouver. So prestigious and historical was this undertaking that the ocean-going vessel named Lootaas—Haida for Wave Eater—was positioned in front of the Royal Yacht Britannia for the opening ceremony. No one ever imagined that this cedar canoe would set the final dramatic stage for the thirteen-year struggle to save South Moresby.

Since Bill Reid had opened the door for the Islands Protection Society to publish Islands at the Edge: Preserving the Queen Charlotte Islands Wilderness, I had been spending more and more time with him, turning a casual relationship into a deep friendship. Guujaaw continued assisting Bill in creating his final legacy of masterpieces, so the invitation was always open for me to spend time in Bill’s Granville Island studio while visiting Guujaaw in Vancouver. Watching Bill’s monumental creations transform from mere sketches on scraps of paper into world-renowned works of art was awe-inspiring. There was his stunning yellow cedar sculpture The Raven and the First Men (1980), which now graces the rotunda hall of the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, followed by the monumental bronze sculpture of the Haida Killer Whale, Chief of the Undersea World that guards the entrance to the Vancouver Aquarium. Some of Bill’s creations were pure whimsy, like a frog with bulging eyes you could pull around on rollers that Bill called Phyllidula, the Shape of Frogs to Come.

Bill Reid immortalized the Haida creation story in his carving, The Raven and the First Men, which now graces the rotunda of the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia.

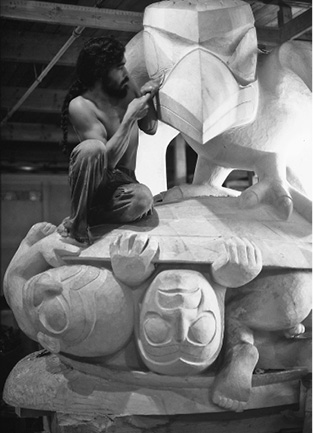

Guujaaw sits atop a giant clamshell while working on Bill Reid’s sculpture The Raven and the First Men. Richard Krieger photo

Bill’s thirty-year struggle with Parkinson’s disease was taking a frightening toll on his abilities by the time I got to know him well. He seemed almost possessed in his determination to leave as lasting a legacy as possible before the scourge claimed his life. I watched him model and cast what may go down as his greatest achievement—The Spirit of Haida Gwaii (The Black Canoe)—a colossal, five-thousand-kilogram bronze sculpture commissioned for the Canadian embassy in Washington, DC, in 1989. A twin casting in 1996 called The Jade Canoe was created for the main lobby of the Vancouver International Airport and became such an iconic national symbol the image was used to grace the Canadian $20 banknote.

For this crowning achievement, Bill deliberately crowded all the Haida mythological creatures into the canoe facing different directions as a mischievous statement about Haida politics; he privately referred to it as the Ship of Fools. No one infuriated the Haida more or endowed them with greater pride in their culture than Bill Reid. His often glib comments seemed insensitive. When asked by the media how he felt about the renaissance in Haida art catalyzed by his work, he replied, “What renaissance? Most Haida don’t know which end of a hatchet to hold.”

From having frequent dinners together, often at his house, and assisting him in his wheelchair to various gallery openings, I knew that Bill’s words often came not from his heart, but the pain and heavy medication he was on for his fatal condition. His spirit was totally with the Haida Nation, and he demonstrated that repeatedly with his support for Rediscovery and elevating the South Moresby cause. Had it not been for Bill hosting a gathering of influential people at his house that was attended by Maurice Strong, founding director of the United Nations Environment Program, Rediscovery might never have expanded beyond the shores of Haida Gwaii: it was at a Rediscovery slideshow I presented in Bill’s apartment that Maurice’s wife, Hanne, invited me to Colorado to start up a Rediscovery program for the Ute, Pueblo and Navajo tribes.

Bill Reid’s famous sculpture, The Jade Canoe is installed in the lobby of the Vancouver International Airport. It is a replica of The Spirit of Haida Gwaii (The Black Canoe)—a colossal, five-thousand-kilogram bronze sculpture commissioned for the Canadian embassy in Washington, DC.

Bill Reid loved the idea of a reawakening of Indigenous cultures on the coast. Even though he was refused permission to build a home and studio in Skidegate Village due to his half-Haida heritage and lack of Indian status, he used to lobby me hard to set up a Haida village on a small island just offshore from Skidegate so Haida elementary schoolchildren could have a place to go for cultural immersion and outdoor education after school hours.

The last time I saw Bill, shortly before he passed away on March 13, 1998, was when I dropped in on him unexpectedly for a quick courtesy call along with Justin Nelson, a young Nuxalk boy from Bella Coola who had been taking the Rediscovery training I was facilitating at United World College. With barely an introduction and not an ounce of intimidation, Justin walked right across Bill’s living-room floor, took a masterpiece painted drum from the wall and said, “Mind if I drum you a song, Mr. Reid?” Had any of Bill’s agents or art groupies been present they would have scolded Justin for his insolence and found him an unpainted drum.

Not Bill. “That would be good,” he replied.

While risking rubbing off some of the priceless painting on the drum skin to warm the hide with the palm of his hand, Justin proclaimed the ownership of the song he was about to sing. “Long ago when our chiefs first came to the Bella Coola Valley, they danced down the eyelashes of the sun singing this song. It has been handed down through the generations to Chief Lawrence Pootlas.” As Justin began the song in his powerful feast-house voice, Bill almost shot out of his wheelchair in excitement. Moved as much by the vivid imagery of the story as the song, he was mesmerized, with both arms banging the sides of the wheelchair and both feet pounding the floor to the drumbeat. The Chief Lawrence Pootlas song is certainly one of the most powerful and beautifully composed on the entire coast. When the song ended, Justin casually hung the now well-used drum back on the wall and said in parting, “Mind if I visit you again, Mr. Reid, and sing you another song?”

Bill was still frozen in his wheelchair, eyes as wide as saucers, when he replied what would become the last words I would hear from him: “That would be good!”

Bill always considered the carving of the fifteen-metre Haida war canoe Lootaas, from a massive red cedar tree, his greatest accomplishment. His monumental sculptures, prints and elegant gold and silver castings of Haida legendary beings were impressive enough to draw world admiration, but the canoe spoke more directly to the Haida as a living, vibrant, moving culture. Appropriately, it was in Lootaas that Bill Reid’s ashes were ultimately carried to Tanu, where I attended the scattering on the soil of his mother’s ancestral village.

Years before, in the spring of 1987, Bill was trying to solicit Haida paddlers to take the Expo 86 canoe back to Haida Gwaii. The Skidegate Band Council had persuaded the bank that commissioned the piece to donate it back to the Islands, home of the cedar tree it was crafted from. Originally, the plan was to transport the massive vessel aboard a barge, but Haida pride could not allow that. Frank Brown, a young Heiltsuk man who had the worst record for juvenile crime in his mid-coast community of Bella Bella, had done something that took the World Exposition by surprise. He decided it was time he gave something back to his community, so he cut down a cedar tree, hollowed it into a traditional Heiltsuk canoe, trained a crew of village kids his own age and, using beach boulders as ballast, paddled all the way to Vancouver. Frank Brown’s canoe pulled into False Creek in the middle of the Expo 86 ceremonies, to the surprise of everyone. He required no bank to commission his undertaking. It was clear from this act that the renaissance of Indigenous identity on the coast was not restricted to Haida Gwaii or to celebrated artists; it was coming from all quarters.

Frank Brown’s initiative would in time mark the rebirth of canoe tribal journeys from Washington State to Alaska, but for now it posed a quandary. It was a silent Heiltsuk challenge but a culturally important one, and the Haida knew they would be compelled to paddle the Lootaas home to Haida Gwaii. The Vikings of the North Pacific and Lords of the Coast could never bear the humiliation of barging a Haida war canoe across their ancestral sea lanes while other nations were paddling.

In the spring of 1987, during one of my many visits to Bill Reid’s studio, I overheard him complaining that he couldn’t get any Haida to paddle the canoe north. “They all want money,” he grumbled. “I’m just trying to get the damn thing up there.” Most young Haida saw Bill Reid as fantastically wealthy compared to the poverty and chronic unemployment that was their reality. Naturally, they were looking for financial compensation, but Bill had no such funds. “Hell, I’ll let the Vancouver Rowing Club’s women’s team paddle Lootaas to Haida Gwaii at no cost,” Bill told me in frustration.

“Don’t do that,” I pleaded. “I’ll find you a Haida team who will pull the canoe for free.”

“Where?”

“Rediscovery kids will do it!” And so it was that I got on a plane from Vancouver to Haida Gwaii with forty-eight hours to come up with a paddling team to pull a fifteen-metre Haida war canoe through nine hundred kilometres of coastal waters for the first time in over a century.

Arriving in Masset after dark and standing under a lamppost in the almost exact location I ended up after disembarking the Northland Navigation freighter on my first arrival fourteen years earlier, I was contemplating where to begin in co-ordinating the biggest Haida cultural event of the twentieth century. Just then, RCMP Constable Alan Wilson, the arresting officer of the elders during the Lyell Island blockade, pulled up beside me in his squad car. “What are you doing back on the Islands, Huck?” he greeted me warmly, extending a hand to shake.

“I’ve got two days to put together a paddling team to bring Lootaas back from Vancouver,” I replied.

“Stay right here,” Constable Wilson ordered me. He turned on his squad car siren and flashing lights and raced off to Old Massett village. It was not hard for a cop to locate former Rediscovery participants; everyone knew everyone else in the village, and many of the boys had been corrections referrals to the camp at some point in their lives.

As soon as Constable Wilson’s squad car pulled up beside me with an excited crew of young men and women, we embraced as Rediscovery family and Alan raced back for another carload, and several more. I signed them all up and gave them a list of what to bring, and in no time we had our Masset paddling team. I now needed to enrol paddlers from Skidegate, and the Skidegate Band Council got strongly behind the selection. The following morning we all boarded the flight from Sandspit to Vancouver and started the training.

To be honest, Bill was not that far off in his assessment of contemporary Haida skills. Some of the pullers weren’t sure which end of the canoe was the bow or how to hold a paddle, but it took little time before their ancestral genetic encoding kicked in and these kids were ready for the high seas. I was impressed to see how quickly the paddlers took to their task under the direction of Jim Frank, a Haida skipper brought in from Southeast Alaska to head the expedition.

A friend of Bill Reid’s had a large heritage vessel, the Ivanhoe, that he very generously offered as the support boat for the expedition. It would be large enough to bring the Lootaas canoe up alongside, disembark tired and hungry paddlers, grub them up and bed them down for the night in the rather spartan quarters of the ship’s hull. The boat owner and Bill had the staterooms on board, as would be expected, but eventually the disparity in grub proved an issue. Gourmet meals were being served in first class, but the steerage passengers doing all the paddling felt they were not getting the food they needed to keep their energy up. Anyone who has ever lived on Haida Gwaii knows how culturally important food is and what a contentious issue restricting it can be. Because I had a personal and positive relationship with many of the paddlers through Rediscovery, the Skidegate Band Council employed me to oversee the crew and resolve conflicts that might arise between them. As most of the youth had already learned how to resolve differences by passing an eagle feather to designate the sole speaker at Rediscovery camps, the only issue that arose on the Lootaas expedition was the grub. In time that too was resolved to everyone’s satisfaction.

We had only a few days to practise paddling and paint Haida-crest designs on paddles and woven Haida hats for the ceremonial entrances into the villages we planned to visit during the expedition. Bill Reid quickly designed canvas vests for all the paddlers to wear at these events, so the overall impression was an event much better organized than it actually was. The Lootaas expedition would be a historical cultural event followed closely by the press and witnessed by thousands of First Nations peoples at the seven villages where we would be welcomed along the way to Skidegate: Sliammon, Cape Mudge, Alert Bay, Bella Bella, Klemtu, Hartley Bay and Kitkatla. But it was never meant to have a political agenda like the South Moresby train caravan. At least, not until Haida Nation president Buddy Richardson took the stage at the Granville Island launch, telling the BC and federal governments in no uncertain terms that Lootaas would be paddled straight to Lyell Island, where everyone aboard would blockade the logging road and the Haida Nation would call on people throughout the world to join them. This announcement came as news to most of us, and everyone was free to make their own decision on civil disobedience, but if there was a need for a final fire to be lit under the South Moresby cause, Buddy’s impassioned delivery was it.

Archie Samuels practises a paddle song with Guujaaw’s drum aboard Lootaas (Wave Eater) in 1987.

A short-term moratorium had been placed on Lyell Island logging to allow for a cooldown after the seventy-two Haida were arrested at the blockades in November, but now that the story had played itself out in the press, the moratorium was about to be lifted with the issuing of new cutting blocks. In other words, BC would be back to logging business as usual. At least, that was the plan according to the BC Forest Service.

Reg Wesley paints his crest on a Haida hat in preparation for the Lootaas canoe launch in Vancouver.

We departed Granville Island with great fanfare, paddled under the Burrard Bridge with car-honking salutes and set a course along the edge of Stanley Park north to Haida Gwaii. Nothing like this massive canoe, pulled by twenty strong Haida men and women, had been seen in over a century. Paddling out into the protected waters of Georgia Strait, later to become the Salish Sea, we headed straight for the Coast Salish community of Sliammon near Sechelt. Although it was now a bedroom community to the province’s largest metropolis, it was still easy to visualize longhouses standing along the beach where suburban-style houses now stood. We were warmly greeted, feasted and billeted for the night. The next morning before our departure a few of the local youth wanted to experience paddling in Lootaas, and the Haida paddlers obliged them by carrying some of the girls out to the canoe on their shoulders to keep their feet dry. Seeing their young maidens hoisted onto the shoulders of Haida men heading out to a massive war canoe was not a good image for the elders.

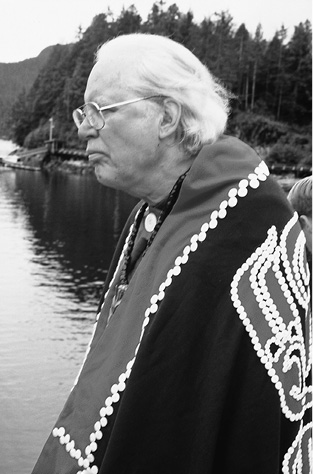

Bill Reid sees his Expo 86 masterpiece Lootaas (Wave Eater) come to life on the paddle expedition from Vancouver to Haida Gwaii in 1987.

At the same time the Lootaas expedition was historical and supported as a seminal Coastal First Nations event, it also had the potential of bringing up age-old animosities. Knowing this, we were careful to follow protocol by always entering a village stern first and formally requesting permission to land. The Haida’s reputation on the coast as the fiercest warriors preceded us, so the paddlers had to rehearse this manoeuvre many times; a bow-first entry traditionally designated a war-party raid.

Our paddle route took us north to Cape Mudge, the boundary that separates Coast Salish from Kwakiutl territory. The screaming tide rips of Seymour Narrows gave the Lootaas paddlers their first real test in navigating dangerous waters. Just past the narrows we pulled into Alert Bay with a rousing welcome by the U’mista Cultural Society and all hereditary chiefs in full regalia. Paddling up to the largest feast house on the coast with its stunning house-frontal design and regally attired welcome party was like a scene out of an Edward Curtis film. With Bill Reid seated ceremoniously in the bow, the Lootaas pullers requested permission to land and then swung the canoe around to do so stern first as protocol dictated.

Kwakiutl U’mista society dancers welcome Lootaas paddlers in front of Alert Bay’s famous big house.

The feast, songs and masked-dance performances that night in the Alert Bay big house were spectacular, but one moment especially stood out for me. Chief Archie Robinson from Klemtu, also known as Kitasoo, stepped forward and invited the Lootaas paddlers to his village much farther up the coast. This was not on our original paddling route, as it took us out of the way, but the invitation had been given in the proper way, announced in the feast house, and protocol made it compulsory that we accept.

Haida paddlers in slickers—Audrey Collison, Robert Cross, Diane Brown and Neika Collison—prepare for a wet day at sea as they depart from the support vessel MV Ivanhoe during the historic 1987 Lootaas expedition.

Departing from the relatively safe waters of the Inside Passage, Lootaas now paddled out into the open waters of Queen Charlotte Sound. What could have proven one of the greatest challenges of the entire trip turned out to be a flat, calm, duck-pond day. The real adventure came days later after a wonderful stay in Bella Bella when Lootaas had to cross Milbanke Sound. The support vessel, Ivanhoe, broke down that day once the initial paddling crew had set off after breakfast with limited food and water. There was no way to do the planned crew change or get additional supplies to the canoe with the support vessel down. We always had a mixed crew of young men and women, so paddlers needing to relieve themselves had to wrap themselves in a blanket and do their business in a bucket. It was not a pretty sight. By the time we got Ivanhoe up and running again, Lootaas had crossed the Sound and was making a beeline for Kitasoo in the dark. The support vessel attempted to rush ahead to anchor offshore and disembark the documentary film crew before the canoe’s arrival, but it was too late. Cussing like sailors that they were missing the most important scene on the trip, the film crew was stuck on board, but I was happy. The Haida paddlers deserved this moment all to themselves, I felt, for they had given everything they had of their spirits and bodies to get there.

Nothing like this had happened in Kitasoo, the southernmost of the Tsimshian villages on the coast, for over a century. Once Chief Archie Robinson’s invitation had been formally accepted in Alert Bay, his villagers frantically prepared for the Lootaas’s arrival. There wasn’t much of a cultural revival in Kitasoo at that time so button blankets and headdresses had to be quickly fashioned for the welcoming party. We later learned that the entire community had been formally standing on the beach, singing and waiting for the Lootaas since sunset; it was now nearly midnight when a Haida paddling song somewhere in the dark met the Kitasoo songs of welcome coming from shore.

As the massive prow of Lootaas emerged from the gloom of night, the welcoming party fell completely silent. The Haida paddlers, exhausted from sixteen hours at sea and looking as wild as their forefathers in a war raid, requested permission to come ashore only to be met with a profound and prolonged silence. At long last, Chief Archie Robinson spoke up with the words, “Haida people, it is with mixed emotions we greet you here tonight, for the last time your people arrived in the dark very few of us survived.” Again there was a painfully long silence; centuries of mistrust and animosity had to be reconciled in each person’s heart in the dark of the coastal wilderness. The exhausted paddlers had no idea what they were walking into when they disembarked. “Okay, come ashore,” the chief finally broke the tense silence. “The food is on.”

Kitasoo would experience a cultural renaissance following this event, building the most beautiful feast houses on the coast near the point where we landed and starting up their own Rediscovery program and ecotourism ventures in the Great Bear Rainforest, but for this night the Haida and Tsimshian were happy to just peacefully meet and eat together.

The daily routine involved in paddling the nine hundred kilometres up the coast made it hard to recall every high point, but a highlight for the entire expedition was spending a night camping on a beautiful white-sand beach in the middle of what would later be designated the Great Bear Rainforest. This was the mainland counterpart to Gwaii Haanas, lying directly east of it. The pristine wilderness with its many islands, deep inland fjords, climax forests and glacier-capped mountains deserved equal protection, as it was also the home of the Kermode or Spirit Bear. Guujaaw had been working with Islands residents for years trying to stop the hunting of the Haida Gwaii black bear, but to no avail. I’ll never forget the phone conversation we had when I returned from a trip overseas and learned through Guujaaw that the Great Bear Rainforest had been granted protection.

“You know why they did it?” Guujaaw asked me.

“Because of the Spirit Bears?”

“Because they’re white!” he answered firmly. I laughed, but his point could not be refuted.

Our overnight camp on one of the islands of the Great Bear Rainforest was especially memorable after weeks of sleeping aboard the Ivanhoe or being billeted in villages after late-night feasts because the paddlers were suddenly free of protocols and expectations. They played on the beach like otters and spontaneously began rehearsing a new dance to a drum song they heard carried on the wind. This would prove especially poignant at the end of the journey.

From Kitasoo we paddled north to the Tsimshian village of Kitkatla before attempting the crossing of notorious Hecate Strait. Some paddlers were falling ill by this point, and others had tendinitis in their wrists from the seemingly endless hours and days of paddling. One day I was asked to fill in for a tired paddler, but I protested. “Come on, you guys. You said this was going to be done by only the Haida.”

“Hell, you’re a Haida, Huck. Get in here,” members of the crew replied almost in unison.

And so I did, but just long enough to see the genius in the design of this craft that rode the waves better than any fishing boat I’d ever been on. Wave Eater was the perfect name for a canoe that cut through each mounting crest with the ease of a surf master. Lootaas was buoyant but stable, with lead weights lining a groove in the hull for ballast and an automatic bilge pump to take care of any errant waves breaking over the gunwales. Safe as the vessel was, we still felt it prudent to have a few Haida seiners escort the boat on the final journey across Hecate Strait to Haida Gwaii.

Lootaas cuts a proud image as it plies the coast during the long voyage from Vancouver to Skidegate.

Ten thousand years ago, Hecate Strait was a broad coastal plain giving access to the Haida Islands for caribou, grizzlies and other mainland fauna. The Skeena and Nass Rivers ran through this plain, providing a cornucopia of migratory fish, from the oil-rich oolichan to all five species of Pacific salmon. But then the sea levels rose at the close of the ice age, forming the shallow yet dangerous Hecate Strait. The prevailing southeasterly wind can whip up seas here in a matter of minutes, so timing was everything in making the crossing in a canoe. We waited out the weather a bit, knowing that if we missed a window of opportunity it might be our last for a week or more. A great welcome feast was being planned for the landing in Skidegate and we couldn’t arrive too early—or worse, too late. On the evening of July 8, the barometer was rising and the decision was made to do the sixty-kilometre crossing in the calm of the night. It went without incident and the next morning the prow of a Haida canoe made a historic landing on Haida Gwaii. It was hard to contain the excitement of the crew, but contain it we had to, as we were not due to land in Skidegate for another two days. We hid out in a small cove south of Gray Bay on Louise Island, biding time until July 11 when Lootaas made its triumphant entry into Skidegate.

A Heiltsuk chief stands proudly on the bow of Lootaas as it arrives at Bella Bella. Arriving home in Haida Gwaii was the only time Lootaas paddlers could land their craft bow-first during the entire expedition. In others’ tribal territories, a bow-first landing would have designated a war party.

After Buddy’s bombastic declaration at the Lootaas launch, delivered with all the confidence of an elected leader holding a powerful mandate from his people, both levels of government kicked into high gear. While Guujaaw and I were blissfully leading the canoe expedition through the scenic Inside Passage, the phone lines between Ottawa and Victoria had been burning up trying to reach a settlement. They eventually did on July 7—a $138-million payout to the province of BC by the government of Canada.

Raven, the trickster who makes things happen unintentionally and inadvertently, was at his very best this day. Not only was the first Haida canoe arriving from Vancouver in more than a hundred years, but a memorandum of understanding was signed the same day by the provincial and federal governments to protect South Moresby along the boundary lines first proposed by Guujaaw and me in October of 1974. It was beyond belief! As Guujaaw said later, “There were so many places where people could have quit and said we lost. We lost every battle all the way through, but won the war. The rightness of what we were doing saw it through. Everyone coming into it was new to the cause; the issue was older than any politician’s term in office by the time it was done.”

From left to right: Federal Environment Minister Tom McMillan, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, BC Premier Bill Vander Zalm and BC Minister of Environment and Parks Bruce Strachan sign the historic Memorandum of Understanding to protect South Moresby on the same day the Lootaas expedition arrived in Skidegate from Vancouver on July 11, 1987. bristol foster photo

Against all odds, Beban Logging prepares its equipment to depart Lyell Island after the Memorandum of Understanding was signed between the federal and provincial governments to protect South Moresby. Jeffrey Gibbs photo

The moment I stepped onto the beach, congratulatory crowds and colleagues in the conservation movement mobbed me. Many of them had flown in from Vancouver and Ottawa for the celebration, but my spirit was still very much a part of the Lootaas team and when I was invited to sit with them in the place of honour in the feast hall, I accepted. When I was acknowledged by the master of ceremonies and asked to stand, the Lootaas team started a thunderous ovation that spread throughout the hall; it moved me more than any recognition I have received in my life. “Huckleberry is pretty popular around here,” the master of ceremonies said when the ovation died down. But the real highlight of the night for me came later. It was not the cutting of the celebratory cake or the distinguished dignitaries who spoke. Instead, the moment came when the paddlers were introduced and began singing the drum song that had come to them on the waves and performing the new dance they had choreographed at the island camp a week earlier. I had never seen a moment like that in all the years I’d attended Haida feasts, or any other event in the world during my travels. The entire assembly rose in unison, cheering wildly and pounding their feet on the bleachers; elders were weeping. “The land still speaks to our youth,” I overheard one of them saying, choked with emotion. No longer were the Haida reaching into their ancestral treasure boxes to retrieve remnants of a culture that had been largely stolen from them. It was clear to all present that Haida culture was alive, in the moment, and moving forward with confidence. That night we were witnessing more than a landmark agreement in the history of Canada; it was the transformation of a nation.

A South Moresby celebration cake, kept frozen for years as politicians debated the fate of the area, is about to be cut by Speaker of the House of Commons John Fraser (holding cake) along with Colleen McCrory (left), John Broadhead (second from right) and Vicky Husband (right) at the historic signing of the Memorandum of Understanding and Lootaas arrival feast in Skidegate on July 11, 1987. Jeffrey Gibbs photo