Chapter XIV

Full Circle

Serendipity is a wonderfully expressive word, coined by English writer Horace Walpole in his 1754 Persian fairy tale “The Three Princes of Serendip.” Walpole based his new word on the old name for Sri Lanka—Serendib—to describe the three princes in his book who were repeatedly making discoveries, through accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of. That sounded like my story—a series of happy accidents and unintentional outcomes that kept bringing me back to Haida Gwaii no matter how far away I roamed.

In the summer of 2013 my involvement on Haida Gwaii came full circle in more ways than one. Parks Canada was celebrating twenty years of the Gwaii Haanas Agreement, the cornerstone of a groundbreaking co-operative management relationship between the Haida Nation and the government of Canada. So successful is this relationship that National Geographic Traveler magazine has called Gwaii Haanas the best-managed national park in North America and Indigenous peoples and foreign nations sent delegates to Haida Gwaii to see how they had achieved it. The Archipelago Management Board, composed of an equal number of Haida and government of Canada representatives, was now renowned throughout the world as a model for cultural and natural resource governance.

The federal government knew there was much to celebrate when it commissioned the carving of a forty-two-foot monumental pole to mark the twentieth anniversary of the Gwaii Haanas Agreement. They conveniently overlooked a campaign that had really begun nearly forty years earlier when Guujaaw and I drew the line to save Gwaii Haanas, but Parks Canada had not supported it at the time.

It seemed more than appropriate that Guujaaw’s second son, Jaalen Edenshaw, would be chosen from accomplished Haida carvers by a six-person selection committee to carve the Legacy Pole. Proposals had to be put before the committee with no names attached so they would be evaluated by storyline and design alone. I had watched Jaalen grow up from the day of his birth in 1980 and was always amazed at his vivid storybook imagination, bequeathed to him by Jenny Nelson, his elementary schoolteacher and mom. Guujaaw instilled in his second son a profound sense of Haida identity combined with the carving skills and courage needed to release mythological creatures from deep within the wood. Jaalen’s older brother Gwaai, himself a master carver in gold and silver jewelry, had already collaborated with his brother on the Two Brothers pole raised in Jasper National Park, Alberta, before joining Jaalen on this endeavour. Together with Tyler York, a friend from Skidegate, the young men now undertook the slow, chip-by-chip process of creating a monumental masterpiece from a five-hundred-year-old cedar tree.

The pole design was selected for its “land, sea, people” theme, inspired by the connections between the Haida Nation and all those who take care of Gwaii Haanas from mountaintop to sea floor. Parks Canada claims that Gwaii Haanas is the only park in the world offering total protection from the highest summits of the land mass to the abyssal depths of the sea, though the claim is not entirely true as the area is still open to commercial fishing. The pole was to officially tell the story of how Canada and the Haida Nation came together through a historic agreement to protect Gwaii Haanas, but Jaalen had grown up with the South Moresby struggle and was not about to exclude that history from the design. To commemorate all those who had participated in protests and arrests at Athlii Gwaii (Lyell Island), he put gumboots on the three Haida Watchmen figures near the top of the pole—real gumboots—to remind everyone of the sacrifices those arrested had made. It was a whimsical touch that only Jaalen could have come up with, but it will be a lasting legacy to his humour and creativity.

Jaalen also carved “Sacred One Standing Still and Moving” onto the pole—the Haida supernatural being responsible for earthquakes. This figure honours the 7.7-magnitude earthquake in October 2012 that cut off the flow of geothermal waters to Hotspring Island. It seemed ironic that the only island in Gwaii Haanas that Parks Canada ever fought to protect because of its hot springs’ recreational value had the tap turned off by Sacred One Standing Still and Moving.

No longer kids, Guujaaw’s sons and Legacy Pole carvers, Jaalen (left) and Gwaai (right), pose with Justin Trudeau at the completion of the pole raising at Windy Bay.

Mary Swanson, my Haida mother through adoption, was asked to bless the pole as it was carried from the carving studio to the Gwaii Haanas II boat that would tow it to Windy Bay. This was increasingly becoming a family affair and I needed to be there. While Parks Canada had never mentioned anyone’s involvement prior to the Haida logging blockade in connection with saving Gwaii Haanas, the Haida Nation had not forgotten and I was formally invited to the pole raising and the feast that followed a few days later in Skidegate Village. As soon as I heard that the pole raising was to be in Windy Bay and that Uncle Percy Williams would be present, I commissioned a friend, Rod Brown in Terrace, to carve a yellow cedar eagle to present as a gift to the revered elder. It had been forty years since I’d found the real eagle carcass on the Windy Bay beach that I presented to Percy Williams at Vertical Point, so a carved eagle depicting features of Gwaii Haanas etched and wood-burned into the feathers—towering cedars, salmon, black bears, starfish and seabirds—seemed quite appropriate.

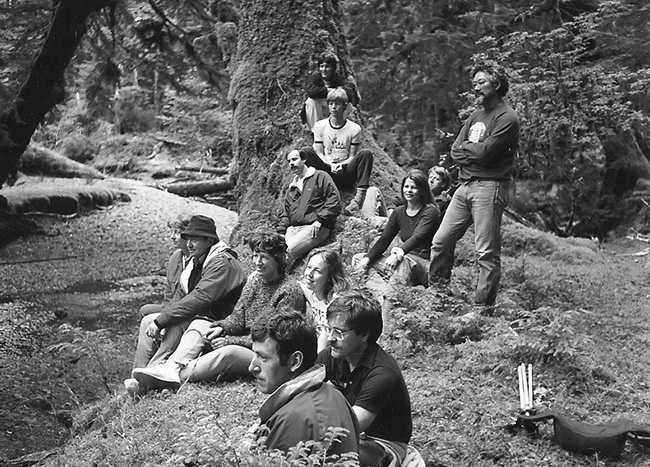

The South Moresby campaign’s principal players gather together at Windy Bay in 1988 to celebrate the signing of the South Moresby Agreement—an early victory in the long process to protect Gwaii Haanas.

It was a huge undertaking moving four hundred guests to the remote Gwaii Haanas wilderness on August 15, 2013 to raise the Legacy Pole at Hlk’yah GaawGa (Windy Bay). A fleet of ships was departing from Queen Charlotte City dock at first light and I had reservations to sail aboard the largest of them. The ship was filled with so many Haida friends and other Islanders who had been instrumental in saving Gwaii Haanas that I felt I was aboard a family reunion cruise. With boats arriving from all directions, Windy Bay looked like a yacht club by the time we arrived to a salute of ships’ whistles. As I disembarked on the clean gravel beach, Guujaaw was there to greet me in the same location we’d held the celebratory feast to mark the signing of the South Moresby Agreement in 1988. It was great to see Jaalen and Gwaai again, both putting finishing touches on a pole, in typical Haida fashion, just hours before it would be raised.

I am pictured here with (from left to right) John Broadhead, Ann Haig-Brown (the wife of Roderick Haig-Brown) and former House Speaker John Fraser at the Windy Bay celebration in 1988.

A Haida pole raising is a celebratory affair charged with anticipation and the sexual energy one might expect from raising a giant phallus. I can recall the nonstop teasing from the Raven clan women at a pole raising in Old Massett when a Staastas Eagle clan chief struggled for hours to raise a massive cedar pole beside his new longhouse. “Hey, Chief,” they taunted mercilessly. “Leave it to us—we know how to raise a Staastas pole.” Under Haida customary law it is taboo to marry within one’s clan; “an eagle must the raven wed,” so the humour was lost on no one. An eagle carving, a separate carved piece, had to be mounted to the top of the pole once it was off the ground a good distance so as not to damage the wings. As the pole-raising official announced to the two teams of rope pullers (one Eagle clan and one Raven clan), “Okay, stop pulling, it’s time to mount the eagle,” a huge cheer went up from the Raven clan pullers. Hours later the pole was still hanging by ropes halfway to its fully upright position when a Raven woman brought down the house by shouting, “Come on, Chief, it’s been five hours. When are we going to see your erection?”

While I talked with Guujaaw at the much more official Windy Bay pole raising, where this type of humour would have shocked the government officials in attendance, a young man approached and stood directly in front of us. We carried on talking until the stranger reached out his hand to us. “Justin,” he said.

“Yeah, I know,” Guujaaw replied casually as he carried on his conversation with me.

“No, Justin Trudeau,” the man replied. I had not recognized the federal leader of the Liberal Party, but Guujaaw had. He usually made a point of treating people in power like anyone else.

“Do you remember being a little guy at Huck’s cabin in 1976?” Guujaaw asked the future prime minister of Canada. It had been thirty-seven years since Pierre and Margaret Trudeau had visited my cabin on Lepas Bay with Justin and his brothers Sacha and Michel. Aged four at the time, Justin could hardly be expected to remember the event.

“No, I think I must have been too young,” the statesman replied. “Although I do recall my father saying he had a very special place in his heart for these islands.” Nearly four decades earlier, Pierre Trudeau had sent my parents and I personal letters after his visit, including a photo of himself and Justin walking on the beach in front of my cabin.

Before the historic raising of the Gwaii Haanas Legacy Pole, the first new totem pole in the southern islands in 130 years, I decided to take a hike up Windy Bay Creek where I’d had such a profound experience forty years earlier. This was the day that Windy Bay had the largest number of visitors it would probably ever have, and yet I found the same magical solitude here as on my first trip. The bear and deer trail into the woods was now lined with white clamshells to keep visitors from wandering from the path, but other than that simple park “improvement,” it was still a moss-smothered forest, completely enchanting with shafts of light and showers of hemlock needles raining to the ground with every fresh sea breeze that stirred the canopy. Taking time to sit in that cathedral-like setting and calm my mind, I had the most profound sense of coming full circle in my life. By the time I broke the meditation and returned to the beach, the high drama of a Haida pole raising was well under way.

The once and future kings, Pierre Elliott Trudeau walks five-year-old Justin Trudeau along the beach in front of my hippie hut in 1976. Canadian Press photo

Donnie Edenshaw, who had first came out to Rediscovery on Lepas Bay in baby diapers and was now a powerhouse Haida man and singer, was rushing onto the beach from the forest, adorned in hemlock branches and screaming like a goghit—a wild man of the woods. Guujaaw was symbolically trying to tame him with a deer-hoof rattle as they danced around the pole in a tense dramatization. Donnie’s full-page photo had appeared in the July 1987 issue of National Geographic magazine along with my own photo and a story on Rediscovery in a feature article called “Homeland of the Haida.”

Now songs came from out at sea as the Swan Bay and Haida Gwaii Rediscovery crews paddled Bill Reid’s fibreglass replica of Lootaas (called Looplex) and another canoe toward the beach. Haida chiefs in full regalia went down to the shoreline to welcome the Rediscovery youth and grant them permission to come ashore. All of this was taking time, and none of it was on the Parks Canada schedule of events. Ernie Gladstone, the MC for the event, told me that he was between a rock and a hard place trying to not interrupt cultural protocol but still keep to schedule so four hundred people would not become stormbound at Windy Bay should a southeaster blow up. This was, after all, Windy Bay, and the name shows on nautical charts for good reason.

The real test of wills came when Diane Brown, daughter of Ada Yovanovich, who had been one of the elders arrested on Lyell Island, was told there would not be sufficient time to bless the pole; it had to be raised—now! It was clear that the federal government, in spite of twenty years of working closely with the Haida, was still on a sharp learning curve. Protocol is everything at a Haida function; weather doesn’t matter. For a Haida to skimp on ceremony for fear of an approaching storm might actually bring on that storm. Four hundred people stranded in Gwaii Haanas for an extra day or two, or a week? So what? Time to start clam digging, jigging for rockfish from the headlands, gathering seaweed and picking wild nettles. The pole was going to be blessed. After Diane had wafted eagle down all around the pole, she brought out her grandchildren to do it, one by one, all over again. It may have been the longest pole blessing in Haida history, but it needed to be. An elder was teaching an important lesson about time and priority.

When it finally was time for the pole to be raised, I was shocked to see Rolly Williams taking charge. Rolly was a friend and had been a junior guide on Haida Gwaii Rediscovery when I was program director on the west coast from 1978 to 1985. He was both fearless and reckless, and I’d had to fire him once after he walked out on a tree overhanging a thirty-foot cliff face. He wanted to clear some branches with a chainsaw so the kids in camp could get a better swing from a rope, but he was endangering his life and those below him. Now he was in charge of safely raising a forty-two-foot cedar log weighing 214,000 pounds over a crowd of approximately four hundred. I bit my knuckles out of sheer nervousness, but Rolly performed the task more calmly and easily than any pole raising I had ever witnessed. With just a few soft-spoken commands, he had the Legacy Pole standing upright to the cheers of the hundreds on the beach and a nearly equal number of people witnessing the pole raising via a livestream feed on the big screen at the Haida Heritage Centre back in Skidegate. He was definitely the right man for the job.

My only regret at the pole raising was that Uncle Percy Williams was feeling too weak that day to make the trip to Windy Bay. I asked Ernie Gladstone if I could have a minute to present the carved eagle gift to Guujaaw so he could present it to his uncle. “Sorry, Huck, there’s no time,” Ernie replied. “We’ve got to get everyone on boats and get out of here before the weather comes up; you can present it at the feast in Skidegate, okay?” I was fine with that, but I had to remind Ernie of his promise two days later as over a thousand people crammed into the Skidegate hall for the commemorative feast on August 17.

Coming full circle with Rediscovery, I share a moment with former program director Marnie York (left) and Rolly Williams (centre)—a former Rediscovery participant and staff member now in charge of the pole raising at Windy Bay in 2013.

It took hundreds of pullers to raise the Legacy Pole at Windy Bay, among them Justin Trudeau, the future prime minister of Canada.

If ever there was an event on Haida Gwaii that brought together the full renaissance of Haida culture, this was it. As the hereditary chiefs from both Masset and Skidegate were announced entering the hall, everyone rose in respect. Sharing the master of ceremonies role this night were former Rediscovery youth who had not only found their big-house voices, they were speaking in fluent Haida. I had the honour of sitting beside my adopted Haida mother, Mary Swanson, who had devoted her past forty years to teaching Haida language in the schools. At age ninety and receiving blood transfusions twice a week to stay alive, she was still teaching. Every missionary and residential schoolteacher who had ever slapped a Haida child in the face for speaking their own language would be rolling over in their graves if they witnessed this night. The Haida Nation had not only survived a century of state-sanctioned ethnocide, they seemed stronger despite it.

Guujaaw beats his bear design drum at the first Windy Bay celebration following the preservation of South Moresby in 1988.

The federal government had set out a strict schedule of speakers to adhere to, but the Haida found their own voice on this night. Buddy Richardson boomed from the entranceway, “We stand for our rights; Lyell Island will not be logged,” as all seventy-two Haida who had been arrested on Lyell Island in 1985 solemnly paraded into the hall and a thousand cheering people rose to their feet in tribute. There followed spectacular masked dance performances telling the stories of Foam Woman, and of the first spruce tree that colonized Haida Gwaii after the retreat of the ice sheet. This was not a show staged for spectators so much as the unveiling of a cultural legacy and oral history three times older than the oldest books.

A Haida spirit dancer blesses and cleanses the feast hall for the opening of the Gwaii Haanas Agreement’s twentieth-anniversary celebration in 2013.

It was an incredible night, but I was getting pressed for time as I had promised to drive my Haida mother onto the ferry to the mainland departing at 10:00 p.m. She was heading to a big potlatch in Alaska so I could not linger too long at this event. I asked Ernie Gladstone when I could present the eagle carving to Percy Williams. “He’s on the list of speakers,” Ernie said. “Do you want to present before or after him?” After seemed more respectful. When Chief Percy Williams rose to speak he had the room’s complete attention; he was, after all, the eldest chief present. “Where is Huckleberry, Thom Henley?” he asked, looking around the room as he opened his talk. I stood briefly to be acknowledged and then he went on to tell the story of our first meeting at Vertical Point in the summer of 1973. Ernie Gladstone, who was sticking his neck out allowing me to speak, flashed me a quick thumbs-up from behind the speaker’s podium. He now had the excuse he needed to break from the strict speaker schedule and call on me to make the presentation.

As soon as Chief Percy sat down I carried the eagle carving to the podium veiled under a red cloth. I thanked the assembly for the opportunity to make the presentation and told the story of serendipitously encountering Uncle Percy in 1973 when I presented him with the eagle carcass I’d found in Windy Bay. I went on to recount how Guujaaw and I had drawn the line that is now the park reserve and how countless people had dedicated over a decade of their lives to creating the global stage the Haida Nation stepped onto at Lyell Island. “Many people here in this room should be acknowledged for their lasting contributions to the event we’re celebrating tonight,” I said. “People like John Broadhead, Richard Krieger, Jack Litrell, Jeff Gibbs and many others.” I went on to talk about how these people had championed the South Moresby cause long before Parks Canada showed any interest. “But it’s different today,” I concluded. “The relationship between the Haida Nation and Parks Canada is so close it’s almost as if the agency has been adopted. But anyone adopted into the Haida Nation, as I have been privileged to be, knows that along with the honour comes responsibility. So if Parks Canada really wants to see Gwaii Haanas protected in perpetuity from mountaintop to sea floor, it now has a responsibility to return to Ottawa and tell this government to stop the needless and reckless expansion of oil ports and tanker traffic in these waters.”

The crowd went wild with applause. After I presented Percy with the carving, the MLA for the Islands rushed up to me to say, “Thank you so much. I’ve been waiting for days for someone to raise that issue.” Haida Gwaii residents were all but unanimously opposed to the Conservative government’s plans to expand oil terminals in the North Pacific so I knew I was preaching to the converted, but I wanted to challenge Parks Canada to show some backbone for once. As fate would have it, the next speaker was the director of national parks for all of Canada. “I’m not sure who the previous speaker was,” he began his talk, searching the speaker list in vain for my name, “but I want everyone here to know I heard his words and will take this message back to Ottawa.” Whether he did or not is uncertain. Harper’s Conservative government approved the pipeline plans shortly thereafter, but it was replaced by Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government in 2015, which pledged to stop the pipeline.

Foam Woman, one of the earliest supernatural beings that appeared when Haida Gwaii “emerged from concealment,” is portrayed at the 2013 celebration through a dramatic mask carved by Jim Hart.

A masked dancer representing the first spruce tree on Haida Gwaii performs a story older than the Bible at the Gwaii Haanas legacy celebration.

Mark Dowie, an investigative historian, recently put the Haida situation in global perspective: “By creatively and patiently using the courts, human blockades, public testimony, and the media—all the while building strategic alliances with environmentalists and neighbouring tribes—the Haida won the support of enough Canadian citizens, government officials and Supreme Court justices to come within reach of a goal that thousands of Indigenous communities around the world have struggled for generations to win … the Haida are only one Supreme Court decision away from obtaining aboriginal title.”

As I was leaving the feast hall to rush Mary Swanson and her daughter Goldie to the ferry terminal, several former Rediscovery participants I had worked with in their youth stopped me in the hallway for hugs. “You never told us that story before, Huck, about you and Uncle Percy and drawing the line with Guujaaw,” they said. “We thought everything started at the Lyell Island blockade. You need to write a new book.”

Riding on the ferry to Prince Rupert that night I had the same melancholy feeling I’d had when I first left the Islands. Haida Gwaii had become home for me in a spiritual sense even if I no longer physically resided there. Why is it, I wondered, that governments are so reluctant to acknowledge citizen actions responsible for saving areas from destruction? I had watched Vicky Husband almost single-handedly save the Khutzeymateen, the world’s first grizzly bear sanctuary, and I’d seen the pivotal role Haisla leader Gerald Amos played in saving the Kitlope, the world’s largest intact temperate rainforest watershed. Peter McAllister had championed protection for the Great Bear Rainforest along the mid-coast, Colleen McCrory had led the campaign to protect the Valhalla Wilderness area in BC’s Interior and Paul George had saved countless areas of British Columbia through the organization he co-founded with photographer Richard Krieger—the Western Canada Wilderness Committee. But nowhere in the history of these protected areas were those who initiated them ever acknowledged. The deliberate slights suggest more than governments wanting to take credit for enlightened policies; it is as if they don’t want to encourage citizens to follow these leads.

Packed to the bleachers, the Skidegate Community Hall hosts the anniversary celebration of the historic Gwaii Haanas Agreement.

While Parks Canada was celebrating twenty years of the Gwaii Haanas Agreement in 2013, I marked the occasion by presenting a carved yellow cedar eagle to Chief Gidansda (Percy Williams) in recognition of the eagle carcass that started it all forty years earlier, in 1973. Jeffrey Gibbs photo

As the Queen of the North ferry made the slow passage across Hecate Strait that night, my mind was preoccupied with thoughts of what our efforts would mean in the end. The world’s population had tripled since I was born, and humans had impacted the earth more in that short span of time than in the last two hundred thousand years since the emergence of Homo sapiens. Over half the world’s wealth has filtered its way into the hands of a mere 2 per cent of the world population, and for many personal greed now far surpasses personal needs.

“Everything you do will be meaningless, but you must do it,” Mohandas K. Gandhi once said. On a cosmological scale there is no denying this statement. I have had the good fortune to experience sixty-eight revolutions around the sun so far, but that is insignificant compared to the 4.6 billion orbits since earth was formed, as has been widely determined by scientists. In universal time we, and our actions, are meaningless; but not in human time. When I see fellow conservationists holding signs like “Save the Earth,” I like to remind them that the earth is not in need of saving and humans are certainly not capable of saving it. Our challenge is to stop mucking it up so it does not shed us off as a species before our time. On average, species survive three to five million years before going extinct, so humanity’s best days should be ahead of us. Our greatest challenge, socially and environmentally, will be having our behaviour catch up with our numbers.

Whenever a religious zealot corners me, I cut short the proselytizing with the question, “What do you think is the most often violated of the Ten Commandments?”

“‘Thou shalt not commit adultery,’” is the usual response.

“Not even close,” I counter. “What about ‘Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s goods’?” That’s all modern society does—covet. We have a global economic system based on coveting. The teaching is a sound one, as is the Buddhist lesson that desire causes pain; when we lose desire for more than meets our needs, we lose the pain associated with not having it.

I was still awake by the time the ferry was pulling into Prince Rupert Harbour at first light. I had arranged a stateroom on board for my Haida mother and sister, but I chose to sit out on the deck myself for the fresh air and possibility of stargazing. The energy of the feast house takes a long time to dissipate, and my thoughts were still very much with what I had witnessed hours earlier. If there’s hope for humanity, I thought, I have just seen it. It lies in young people grounded in the best values of their culture, respecting one another and the earth and not having a shred of doubt in their minds that a future lies in this.

Bill Reid, in his opening chapter to Islands at the Edge, wrote, “When, or if, we should ever decide that subduing is not the only, or even the most desirable way, of making our way through the world, these shining islands may be the signposts that point the way to a renewed, harmonious relationship with this, the only world we’re ever going to have.”

That’s my hope too.