Chapter I

Cloud Busting

I had never heard of Haida Gwaii until the night I first went there at age twenty-three, but in my childhood dreams there always was such a magical place—lost in the Pacific, green and misty and more than a little mysterious. Call it geographical convergence, serendipity or mere coincidence, but somehow that first encounter touched a subconscious wellspring of my earliest memories. Why was it, I wondered, that my childhood crayon drawings never depicted the place of my birth, the cornfields, woodlots and big red barns of the flat Michigan countryside? They depicted instead deep blue seas, towering snow-capped mountains, waves crashing on rocky headlands and tall conifer forests. Haida Gwaii was a world apart from the landscape I grew up in, and it wasn’t even part of the country of my birth, but somehow my unexpected arrival there felt like coming home, truly coming home, for the first time.

It was a long journey to get there, in both the physical and psychological sense. In May of 1970, I left Michigan State University in my third year and decided to hitchhike to Alaska to go backpacking in Mt. McKinley National Park. It was meant to be a summer sojourn from my studies in cultural anthropology and psychology, but it turned into a long-term exile and a radically new direction in my life.

As a student, I had been active in the antiwar movement and had made the conscientious decision to deliberately give up my student deferment status, get reclassified 1-A and refuse induction should the draft board call me to serve in Vietnam. It was an impassioned more than a reasoned decision, as I had never carefully considered the consequences. In my mind, the real draft dodgers were university kids privileged enough to get student deferments while less fortunate Afro-American, Chicano and Indigenous Americans went in their place.

It took weeks to hitchhike the thousands of kilometres from Lansing, Michigan, to Anchorage, Alaska. A great youthful Klondike spirit was burning in my soul as I rode the dusty Alaska Highway in the back of pickup trucks and marvelled at the eternal summer daylight in this Land of the Midnight Sun. With each passing kilometre the land seemed more and more sublime. I watched wolves darting across the road in the dust of the pickup, bull moose with mouths full of water lilies standing chest deep in idyllic little lakes, and sunsets merging seamlessly into sunrises. This was the epic landscape I’d always dreamed of, immortalized in my mind through Jack London novels and the poetry of Robert Service, whose books I had read repeatedly, curled up in a couch in a home too small to contain my spirit and wanderlust. For the first time I felt fully alive, fulfilling both dreams and destiny, at least until I reached Anchorage—a great anticlimax if ever there was one. Looking up and down the busy, car-congested streets with their 1950s faceless buildings, I felt I was back where I’d started—another Lansing plopped down ignobly in the Great Land.

As if to confirm that first negative impression, my first night in Anchorage I was robbed of everything I had. The brand-new Kelty backpack, tent and sleeping bag I had worked so hard to acquire in Michigan were stolen at a youth hostel, along with the gear of everyone else staying there that night. It was an inside job. A few days later I spotted some of my equipment in the window of a Fourth Avenue pawnshop brazenly displaying a sign: “Hock it to me!” The Anchorage police would do nothing to help me reclaim my gear, but as it turned out, it was the most fortunate misfortune ever to befall me.

Still angry and depressed from being ripped off, I was moping around the Anchorage railway station when an old “sourdough” challenged me.

“Why the long face, fella? Looks like you got a dark cloud hanging over ya.” He showed no sympathy for my pitiful tale. “Hell, you don’t need all that fancy camping stuff,” he scolded. “Take this army surplus blanket—I can get me another one at the shelter.” The blanket was dirty, tattered and crawling with enough critters to keep a taxonomist busy for days, but I didn’t want to offend the homeless old coot so I took it.

“Now git yer ass on that freight car there.” He pointed down the tracks. “And don’t hop off ’til ya see McKinley. It’s the biggest mountain in North America,” he hollered after me when I was some distance down the tracks. “Ya sure as hell can’t miss it!”

I sure as hell did.

At that point in my life I wasn’t much of a freight-train hopper, and my jumping-off point turned out to be the tiny interior community of Talkeetna. Denali (the Great One), as I was told the Athabaskan Indigenous peoples had long ago named what later became Mt. McKinley, was clearly visible from Talkeetna, but Mt. McKinley National Park was still a long way off.

A man with a broad grin, a limp leg and a gaggle of adoring dogs spotted me on the single dirt road that ran the three-block length of this log cabin frontier town. “Need a job?” he said warmly without bothering to ask my name or anything else about me.

“Sure,” I responded.

“Fine, then. I need someone to clear the brush beside my hangar over there.” He pointed to a dense thicket of young poplar trees beside a rusty red airplane hangar. “There’s food, and a dry place to roll out your blanket inside, if you like,” he offered kindly, obviously recognizing my need.

I soon discovered it was the legendary Don Sheldon, a celebrated bush pilot who first mapped the Alaska Range and had survived a half-dozen bush plane crashes after being shot down in World War II. He was one of the nicest people I could hope to meet given my circumstances.

The hangar was full of mountaineering equipment and freeze-dried food left over from McKinley expeditions—these would be my rations. The contents and instructions were usually written in German or Japanese, so every meal was a genuine surprise.

While clearing the brush for Sheldon’s new hangar site I somehow became his right-hand man, pumping gas for his planes, packing gear and grub for his expedition drops, and occasionally flying up with him to base camp to deliver supplies. He loved to airdrop gallons of hard ice cream on top of McKinley climbers struggling with the continent’s coldest and loftiest heights. He loved to tease me too. “Look, ptarmigan tracks in the snow,” he was fond of saying while circling the plane from an absurdly high vantage point. A quick drop and a ski landing on a snowfield would always prove his point.

“Look Thom, ptarmigan tracks,” legendary bush pilot Don Sheldon was fond of saying to me from absurdly high elevations above the Alaska Range as we’d fly in supplies to climbers on Mount McKinley. The “bad-ass bush pilot,” who had survived multiple plane crashes and mapped the Alaska Range, befriended me in Talkeetna and employed me as his right-hand man in the summer of 1970. Grey Villet photo, The Life Picture Collection, Getty Images

Sheldon kept trying to get me to go up for a weekend at his tiny one-room hut on the Ruth Amphitheater—one of the largest and highest glacial fields in the Alaska Range. Some Talkeetna folks cautioned me, however, telling of the time he forgot a guest and left him stranded in that hut for nearly a month without much food. “He’s a bit absent-minded, you know,” they’d say, sitting around the communal dinner table at Talkeetna’s iconic Roadhouse Inn, kicking back coffee that would make your hair stand straight after the best homemade dinner in Alaska.

One week I shared the hangar with a Japanese man, seven years my senior, named Naomi Uemura, who never let on that he was Japan’s greatest hero. We’d fish for grayling together at the confluence of the Chulitna, Susitna and Talkeetna Rivers where the great sweep of the Alaska Range was stunningly visible, at least during the rare times the clouds parted. Naomi always seemed more intent on watching the clouds veiling and unveiling the continent’s highest summits than watching his fishing lure. He had such a sincere honesty, unassuming nature and genuine interest in what I was doing that it never occurred to me the guy could be famous.

Naomi Uimara took this self-portrait atop Mt. McKinley. He was the first person to reach the top alone. Wikipedia photo

One day finally dawned cloudless. Denali (Mt. McKinley) was clear from its base to its 6,190-metre (20,310-foot) majestic summit, and both Sheldon and my Japanese friend flew off so early I was still in my sleeping bag in the hangar. I hope Naomi’s not going for the Ruth Amphitheater offer, I thought as I rubbed the sleep from my eyes. Ten days later on August 26, 1970, I read the banner headlines in the Anchorage Daily Times: “McKinley Climbed Solo!” There was the grinning picture of Naomi taking a self-portrait with a timer on the highest summit on the North American continent—a summit he reached in half the normal climbing time with an ultralight pack and his indomitable spirit. It was the first solo conquest but not Naomi’s first record-breaking achievement. I learned later that he was the first to reach the North Pole solo and the first to raft solo the length of the Amazon. Tragically, Naomi returned to Alaska fourteen years later to attempt the first winter ascent of Denali, but he disappeared and perished in a storm while descending the summit on February 13, 1984. His words always served as an inspiration to me: “In all the splendor of solitude … it is a test of myself, and one thing I loathe is to have to test myself in front of other people.”

While my hangar buddy was glowing in the publicity of the first solo climb of Denali, little did I know the long arm of the law was starting to reach out for me from Michigan. In the meantime, the state of Alaska had opened land for settlement along the railway, and I joined other back-to-the-landers rushing to stake and claim a five-acre parcel—for free!

Nineteen kilometres up the tracks north of Talkeetna, I found an old abandoned trapper’s cabin that I restored to habitable condition while I searched for the perfect homestead site. In late September I was cutting my winter supply of firewood when the passing train hurled the bag of mail for our little community out the door of the baggage car. It landed close enough for me to walk to it. A letter from my parents marked “Urgent” told me that my summer of love was over: the Michigan Draft Board had sent me an unanswered Notice of Induction while I had been travelling. “The FBI know you’re in Alaska. Get out!” my parents warned. The FBI had questioned some friends and two of my younger brothers as to my whereabouts after my departure from Michigan, but it wasn’t until my aunt Ruth inadvertently gave information about my cabin in Talkeetna to an informant posing as a friend that my life underground began.

I packed and headed south just one step ahead of my pursuers. My nearest neighbour and friend Steve Rorick, who lived just over a kilometre south on the tracks, was taken in for questioning by the police. They thought he was Thom Henley, and it took him some time to convince them otherwise.

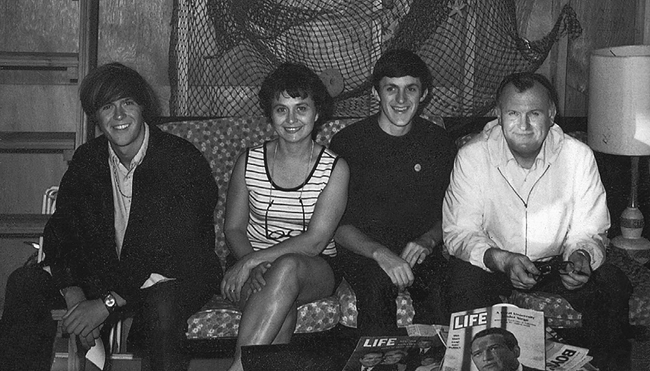

I’m on the left, sitting beside my mom (Agnes), older brother (Mike) and dad (Victor) in our Lake Michigan summer cottage. I posed for this photo shortly before hitchhiking to Alaska for a backpacking trip in the summer of 1970. It turned out to be an unexpected one-way journey for life.

It was, for me, a rather shocking transition to go from being an honours student, Boy Scout, altar boy, Junior Rotarian and Ford Foundation Science Award recipient to suddenly becoming a felon wanted on two criminal charges: refusing induction and interstate flight to avoid prosecution. Although my parents, both World War II veterans, did not initially support me in my antiwar stance, they weren’t about to betray me.

More than a little dumbstruck by my sudden predicament, I caught a train south to Anchorage and found myself sharing a coffee with a wino on the city’s notorious Fourth Avenue. He had been hitting on me for some spare change for booze, but I agreed only to the coffee. The seriousness of my dilemma had not fully sunk in, and I started mumbling over coffee about my problems with the law when a large dirty hand, stinking with whisky and salvaged cigarette stubs, reached across the table and covered my mouth. “You shut the hell up, boy,” he whispered as he looked around the room to see if anyone had overheard. “You don’t even know who the hell you’re talking to.” If the old geezer had grabbed and shaken me and thrown me into the frigid waters of Cook Inlet, he couldn’t have shocked me more. It was a profoundly personal awakening. I was no longer the “good boy” society had laboured for two decades to mould—I was suddenly an enemy of the state, a felon, traitor and fugitive. I had to get out.

My homeless and alcoholic acquaintance proved to be a shrewd strategist and, fortunately for me, chose to be my partner in crime instead of putting himself back in the booze through possible reward money from turning me in. He was a former Merchant Marine, before the juice got the better of him, and he knew a thing or two about marine law.

“The Wickersham’s leaving tomorrow evening,” he said. “You need to get on it.” The MV Wickersham was a vessel of the Alaska Marine Highway System, which normally plied the inside protected waters between Bellingham, Washington, and the town of Haines on Alaska’s panhandle.

“How’s that gonna help me?” I asked.

“The damn boat’s built in Norway,” the old wino shouted as if I were deaf.

“So what?” I responded with equal belligerence.

My accomplice put his coffee down, pulled one of the cigarette stubs from his tattered shirt pocket, lit it and proceeded to explain the Jones Act. Designed to protect US shipbuilding, this act makes it illegal for a foreign-built vessel to travel from one US port to another without a stop in a foreign country. “If you can get aboard,” he said with the air of a seaman who knew his ropes, “they can’t legally take you off in the USA. The ship must stop in Vancouver.”

I didn’t have enough of the required money to allow legal entry into Canada, but that didn’t deter my strategist. “Take whatever money you got and convert it to traveller’s cheques tomorrow morning,” he told me. “Go back to the bank before closing time, tell them you’ve lost them, and have them replaced … you’ll have double the show money you have now.” It was good advice again. The next morning I headed to the bank.

I phoned in reservations for the sailing and showed up just before the MV Wickersham set sail. This was her first-time-ever feasibility run across the open waters of the Gulf of Alaska, and procedures were anything but fine-tuned. “Where’s your ticket?” the purser demanded as I tried to board at the last minute.

“Didn’t have time to purchase it before the office closed,” I lied while flashing my ID in a phony show of credibility.

“Go to the chief purser’s desk right away and pay for your ticket and your stateroom,” he said as they pulled up the passenger gangway. Of course, I didn’t do what he wanted. I couldn’t afford having my name on any passenger list for police checks. I was a fugitive now; I had a licence to lie.

I stowed away inside a lifeboat with a snug cover. It wasn’t exactly first class, with an old army surplus blanket for bedding and a jar of crunchy peanut butter for food, but at least I was spared the nausea of a ship full of seasick passengers puking in their cabins. All the way out Cook Inlet from Anchorage, I kept hearing on the public address system: “Will passenger Thomas Patrick Henley please report to the chief steward’s office.” By the time we hit the open Gulf of Alaska and a good October gale, the crew didn’t give a damn anymore about who was on board and who wasn’t. By the time we reached Vancouver, the staff was so weary of mopping vomit that they paid no attention to who was departing. Canada Customs and Immigration were considerably more alert.

“You’re not on the passenger list,” they challenged me as I attempted to disembark.

“Must be a typo error.” I shrugged innocently.

“How long do you intend to stay in Canada? How much money are you carrying?” they asked firmly.

“Only a day or two to see the sights,” I answered respectfully, flashing a wad of phony traveller’s cheques. I was in.

A hippie at the dockside recognized a kindred spirit getting off the Wickersham and commented in passing, “Lay low, man. It’s pretty heavy here.” I had no idea what he was talking about. This was Canada, I was safe—or so I thought.

I headed for nearby Stanley Park, which I’d noticed as the ship passed closely by on its way to berth. The maples were in their autumn array, and their red and gold colours, reminding me of Michigan, beckoned to me. I was strolling along a park path with my backpack on, lost deep in thought about what to do next, when a policeman on horseback trotted alongside and forced me off the trail.

“I’m gonna bust you for possession of a weapon,” the officer said sternly.

“What weapon?” I asked in astonishment. I looked in the direction of the officer’s steely gaze and realized he was referring to the skinning knife attached to my belt. “Oh, that’s just my bush knife,” I answered, trying naively to be friendly. “I just came down from Alaska, and everyone up there wears them.” I smiled and started to put the knife inside my backpack.

“Now I guess I’ll bust you for a concealed weapon,” the cop growled. It was obvious I was dealing with an attitude here more than an issue, so I disposed of the knife in a park litter bin.

“Look, smartass,” the cop responded in a venomous tone. “We’ve had our hands tied long enough, but now we’re gonna start winning.” With that cheery thought he rode off, and I searched for a phone booth.

I was told in Alaska that Vancouver had a free hostel set up for American draft dodgers, deserters and conscientious objectors. I counted myself in the third category, as I’d stopped dodging the draft when I deliberately gave up my safe student deferment status at MSU, and I had never enlisted, so deserting was never an option. I did not consider any one of these titles more honourable than the others; I just happened to be a Vietnam War objector, along with more of my generation than the US government was ever willing to admit.

The person who answered the phone at the hostel said they could give me floor space in the basement to roll out my blanket as the house was crammed full, but they also sounded the same seemingly paranoid warning: “It’s pretty heavy around here, man.” It wasn’t until I spotted a newspaper at a bus stop newsstand that I had any idea what was going on. “War Measures Act Declared” read the banner headline in bold five-inch font. Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, a one-time strong civil libertarian, had imposed martial law on the entire country to deal with the kidnapping of a British diplomat and the murder of a French cabinet minister by the Quebec separatist group Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ).

Vancouver’s right-wing Mayor Tom Campbell was using the unprecedented and unrestricted powers to run hippies and draft dodgers out of town. Welcome to Canada, I thought; I now have the same rights as any Canadian citizen—none! I had come here for freedom, but arrived on the day Canada became a police state. The War Measures Act has been invoked only three times in Canadian history: World War I, World War II and the day I arrived as a refugee.

The Vancouver hostel for war objectors was no picnic—two RCMP squad cars were parked out front keeping a twenty-four-hour-a-day watch on the place. As luck would have it, the guy who ran the place had a French Canadian girlfriend, and that made her an FLQ suspect. Anyone arriving or departing from the house was also suspect and was followed. This was certainly not what I had come to Canada for, and it influenced my direction: I would not apply for asylum in a country under martial law—what would be the point?

I needed a quiet place to sort out my life over the winter, I decided. I would then return to Alaska in the spring under an alias identity. “Head out to the west coast of Vancouver Island, man,” I was advised by one of the Canadian volunteers running the hostel. “Lots of ‘heads’ are living on the beach south of Wickaninnish; it’s cool, man. No one will hassle you there.” It was good advice; empty space has always provided Canada’s greatest freedom.

Even though the summer of love was well over in the States, Florencia Bay on the west coast of Vancouver Island was still hippie heaven. I was told the summer crowd there had been enormous, with everyone living right on the beach in makeshift driftwood shacks. The few hardy souls determined to winter over had built more substantial squatter shacks well above the highest winter storm line, nestled in the dense salal and Douglas firs. I found myself drawn to the far northern edge of the beach where, with the experience and knowledge gained by helping neighbours in Alaska build their cabins, I erected a small log cabin on a two-metre bench. It was a mere three-by-four-metre single room made of beach logs, split-cedar shakes for roofing, clear plastic for windows, driftwood planks for floor and furnishings, and half of a fifty-gallon drum washed up on the beach for a rustic wood stove. It was spartan, but it was home. Everyone on the beach had animal or plant names, and I was dubbed Huckleberry for the red huckleberry patch beside my house. I was happy with the nickname as it allowed me time to work out a suitable alias when I returned north.

It was an unforgettable winter, with great west coast gales whipping the sea into such wild fury that metre-deep foam often blanketed the beach like snow. We got snow too, plenty of it, though it never lasted long. Mostly we were hit by hurricane-force winds, and the few hardy winter residents would hunker down and batten their hippie hut hatches while huge thousand-year-old cedar trees toppled in the forest. I’d never felt so small and vulnerable before in my life. But I also felt free, unbelievably so, and unencumbered by social expectations. There was a richness of spirit here in the kindred souls inhabiting the bay, where community clambakes were held and amazing music jams stretched through the surf-crashing night into the wee hours of the morning.

I didn’t know it at the time, but this was also an important education for me. I grew intimately knowledgeable about the Pacific coast, not as an academic exercise, but as a survival imperative. I had a few guide books, but I also learned by trial and error. I discovered that a raw mussel on a hook cast from a headland on a handline made of stinging nettle fibre at the right stage of the tide was sure to land a Tommy cod or other rockfish. I learned where and how to dig for razor clams, horse clams, butter clams, geoducks and cockles; where to gather abalone, chitons, limpets and urchins. I grew up a Midwestern kid on hamburger, potatoes and cornflakes, but now I was stalking the wild onion, sea asparagus, miner’s lettuce, stinging nettle, seaside plantain, chocolate lily and even savouring seaweed. They say that only a fool could starve to death on such a coast, but fools have done it. I was determined not to be one of them.

A wild cat I named Josephine moved in with me that winter and delivered a litter of kittens in my lap. I was amazed at her level of trust. Because I couldn’t afford cat food, I’d gather and steam mussels for her each day. Occasionally she’d suffer a case of paralytic shellfish poisoning. A stiff cat on the floor was my canary-in-the-coal-mine sign to lay off the mussels for a while. Josephine always recovered, of course, and she’d curl up in my lap to purr herself to sleep with no apparent hard feelings.

Because I could not legally work in Canada and could not risk deportation, I had to be careful to obtain needed funds quietly and discreetly. I collected Japanese glass fishing floats that had crossed the Pacific on the Kuroshio Current and been cast high up on the beach by winter storms. Selling them to souvenir shops in the nearby towns of Ucluelet and Tofino could earn me a few bucks. Once every few weeks I would hike the nineteen kilometres from Florencia Bay to Ucluelet collecting beer and pop bottles that had been cast into the ditches by weekend revellers. The deposit refunds never amounted to much, but I could usually outfit myself with a few staples like brown rice, rolled oats, raisins, brown sugar and whole-wheat flour to supplement my wild food diet. When the roadside foraging was especially good I’d treat myself to a pint of ale in the local pub with some salt and vinegar potato chips. These seem like such simple pleasures in retrospect, but mine was a very basic—but joyous—life. I was living on less than $300 a year, an average person’s cigarette budget at the time, but feeling rich beyond measure. It was one of the greatest lessons in my life, as it taught me to never fear poverty.

In the late spring of 1971, Alaska beckoned me back once more. Throngs of migratory birds were flocking north along the Pacific Flyway and I heard the same inexplicable calling. I said goodbye to my cabin, to my new-found friends and to Josephine (yes, the cat was still kicking). She’d do better on a summer diet of wild mice than a winter of mussels, anyway. About the only thing I took with me, besides wonderful memories, was the nickname Huckleberry, which would resurface years later even though I didn’t use it on my own.

My new identity in Alaska would be Thomas A. (for Arctic) Wolf. When I arrived back under my new alias, I took what little savings I had from my beer-bottle collecting and opened a bank account in Anchorage. My pitiful finances didn’t really require a bank account; I was merely after the colour-photo bank card the branch issued. With this simple piece of phony ID, I was able to secure an Alaska driver’s licence and eventually a Social Security card so that I could legally work as Thomas Arctic Wolf. Alaska has always offered fugitive Americans the best perks for first-time criminals.

Some time later the FBI got wise to the Thomas Wolf identity, and I did a fast name change again to that of a friend who looked similar enough for me to use duplicate ID. I will not reveal that full name to protect my accomplice, but I can admit to having to learn to respond to the name Dale while never responding to Thom.

Life in Alaska was a joy. I returned to the trapper’s cabin beside the railway tracks north of Talkeetna, where a small community of back-to-the-landers had been growing. This whistle stop in the wilderness eventually became known on Alaska maps as Chase, and I often wondered how many of the residents there were also on the run. I met wonderful and bizarre characters, people like Dirty Dave, a crazy, burly Chicano biker from Los Angeles who roared up the tracks on his Harley one day. All week long, Dirty Dave would throw his leftovers and table scraps into a big stew pot, then invite all the neighbours over on Saturday for Dirty Dave’s Stew Night. The gruel was always heavily laced with cayenne pepper to suit the Chicano palate and presumably mask the colour and odour, as well as kill the critters crawling in it. Disgusting as it was, you didn’t dare refuse the invitation and risk insulting the host—he was armed and dangerous. “Mighty good, Dirty Dave,” we’d compliment the chef as we gagged back another bite.

Robert Durr and family lived on the back lake, a four-kilometre hike in from the tracks. He was a psychology professor from some Ivy League school back East who had followed Dr. Timothy Leary’s advice to “tune in, turn on and drop out.” His wife made the transition well from cocktail parties and caviar to boiling moose meat over a smoky fire, but they didn’t reject all the refinements of their former lifestyle—halfway along the bush trail to the Durr complex you could always count on hearing classical music echoing with loon calls across the pristine lake.

Denny Dougherty and his partner Edie were two of my closest Talkeetna neighbours and friends. Denny was a star athlete in school and a Vietnam vet who built a five-storey A-frame log cabin on the edge of a little lake. It was an impressive structure but impossible to heat in the winter, and Denny was forever cutting firewood just to keep his water buckets in the kitchen from freezing. He had a larger goal in life—to someday be the first to ascend Nix Olympus—the highest mountain in our solar system, located on Mars. Edie was the more grounded of the two. She had been a fashion model in LA who gave it all up to mush dogs with Denny in Alaska rather than strut her stuff on the catwalks.

There were other characters too numerous to mention here. The history of Alaska and the history of Haida Gwaii, as I would later learn, have been shaped by eccentric characters. I felt fortunate to be among them and to continue my formal schooling with those living on the edge.

Summers in interior Alaska in the early 1970s were fleeting; the snow wasn’t fully gone until June, and it was back on the ground in late October. But there was a timeless quality to the season brought on by the perpetual daylight. I can recall drifting lazily down Arctic rivers in my kayak, watching the low-angled sun set the sky ablaze for hours as it slowly crawled across the horizon to begin a new day’s sunrise. With all this light, flowers and other vegetation didn’t just grow here, they exploded; sometimes a single cabbage required a wheelbarrow to transport it from the garden to the root cellar at the end of August.

Winters in Alaska were pure magic. The snow fell deep in the upper Susitna Valley, where North America’s highest mountains trap the Gulf of Alaska’s moist air moving up Cook Inlet. On many mornings, I had to dig two to three metres up from my cabin doorway to find ground level at the rooftop and step outside to discover a world transformed with dwarf trees. Just the highest tops of the black spruce trees still stood above the snow line. The small log cabin was well insulated by the deep snow, requiring little wood to keep it warm and cozy. The problem was daylight: it was such a fleeting midday phenomenon on the southern horizon that at times I slept right through it into the next night.

A friend took this photo of my dog, Moosejaw, and me in front of the old trapper’s cabin I was living in located nineteen kilometres up the Alaska railway tracks from Talkeetna. The snowfall is always deep in the upper Susitna Valley where the moist air from the Gulf of Alaska is trapped by North America’s highest mountains. Steve Rorick photo

They call the Alaska Railway the Moose Gooser because the engine cars waste so many moose that use the tracks as the only snow-free corridor along the Susitna River. The “cowcatcher” pushes along the dead moose on the front of the engine car until the carcass reaches an elevated trestle, where it gets dumped to the side. There was just such a trestle located near my cabin, and I took advantage of the frozen carcasses to feed my dog, Moosejaw. I was a vegetarian at the time, riding the Moose Gooser to and from Anchorage once a month, where I would stock up on grains, nuts and veggie burgers shipped up from California. When the ecological and moral absurdity of what I was doing finally struck me, I started feeding myself, as well as my dog, from frozen, train-killed moose carcasses. Talk about a radical dietary change; I didn’t use the outhouse for days.

The Alaska Railway ran along the Susitna River close to my cabin and was also known as the Moose Gooser. In the winter months the railway tracks provided a snow-free animal corridor. The engine car’s “cowcatcher” delivered a steady supply of frozen moose carcasses, which at first I fed only to my dog, Moosejaw, but eventually I ate such meat myself. Dmfoss photo, Thinkstock

With cabin fever setting in, I once joined neighbours Denny Dougherty and Steve Rorick on an extended winter pack trip. The −45° Celsius temperatures made this one of the most harrowing experiences of my life. The darkness proved a great challenge. December is altogether the wrong month for winter expeditions. From the time the tent was dropped, the dog team harnessed and the sled loaded and secured, we had only an hour or so of twilight to travel in before total darkness set in and we had to set up camp again and sit out another twenty-two hours. Lighting a fire was a do-or-die predicament, for once the thick mitts came off, one strike of a match was all the time nature allowed before the fingers went too stiff to strike a second one.

Soon after I set off on a week-long winter pack trip with Alaska bush neighbours Denny Dougherty and Steve Rorick and our combined sled dogs, we came to realize that the long December darkness was absolutely the wrong time for such an adventure.

In the end, it was winter darkness, not the cold, that drove me out of Alaska. I’m a bird; I need to fly where there’s light.

In the summer of 1972, I worked the herring spawn fishery in Prince William Sound and saved enough money to purchase a seventeen-foot collapsible Klepper kayak. It was the perfect craft to give me the freedom to explore some of the Yukon and Alaska’s wildest places: the great river systems of the Yukon and Mackenzie, the Porcupine, the Stewart, the Hess, the Ogilvie and Peel. I also built up a bit of a grubstake from firefighting and working the potato harvest in Alaska’s Matanuska Valley. I could now afford a six-month trip “outside,” as Alaskans refer to the rest of the world.

While kayaking alone for months in the Haida Gwaii and Southeast Alaska wilderness, I relied on a camera timer to get a picture of myself coming ashore in my Klepper kayak.

It was already November and bitterly cold when I started hitchhiking south from Fairbanks with my impractical cargo—a large backpack and the collapsible kayak broken down into two big travel bags. Mine was no idle endeavour. I was setting off to kayak the headwaters of the Amazon from Pucallpa to Iquitos, Peru. Standing along the barren highway with tears freezing to my cheeks, I began to wonder if some of Denny Dougherty’s “climbing mountains on Mars” madness hadn’t rubbed off on me. This would be an eleven-thousand-kilometre hitchhiking journey, and only pickup trucks or empty hauling vans could possibly accommodate my load. Dreams die hard and tropical sun beckoned. I pressed on.

After days of being stranded at Haines Junction in the Yukon, unable to get a ride south down the Alaska Highway, I opted for a lift to the seaside community of Haines and stowed away on the ferry to Ketchikan. An island set in the wilderness with no bridges or roads connecting out of town, Ketchikan is not exactly a hitchhiker’s paradise either. Stranded on the dock, I was pondering my predicament when a burly logger walked up to me. “Want some work?” he asked bluntly, with no introductions.

“Sure, why not,” I answered. Before I could ask him exactly what work he had in mind, I was boarded on a Cessna float plane at dockside with all my gear and flown out to Gildersleeve Logging Camp on Prince of Wales Island.

“Here’s yer hard hat, caulk boots and yer bill,” a no-nonsense foreman said when I landed. “You owe us $85 for the flight,” he added when he saw me staring in disbelief at the billing. “Now get to work.” I’d been shanghaied!

It was late November, the first snow had fallen and loggers were walking out in droves to avoid the dangerous conditions, heading instead to warmer pastures—hooker parlours in Seattle. I was to be a “choker man”—the lowest-level job in the camp. Wrapping freezing-cold steel cable around logs buried under a foot of snow was not the tropical holiday I’d had in mind when I left Fairbanks. To make matters worse, the “rigging slinger” was a madman who was consistently blowing the whistle to the “yarder” to start hauling the logs before I was in the clear. The yarder couldn’t see below the steep hill we were working on, so all he had to go on was the rigging slinger’s whistle and singularly sick sense of humour. If it was time for me to die at age twenty-two, then I wanted it to be kayaking whitewater at the headwaters of the Amazon or lost in the Andes, not crushed in an Alaskan clear-cut by a log destined to become toilet paper.

I loathed the logging camp. It was a prison with dollars supplanting guards, providing pizza, pie and pin-ups as perks until payday. Driving in the smoke-filled “crummy” in the first light of dawn, I would look out at the tortured landscape and back at the tortured souls swearing their way to the work site. Rather than gag on cigarette smoke in the crummy where the crew ate their lunches and cussed out every living critter on God’s green earth, I would work my way through the logging slash and take my lunch in the peace of the forest, the only piece we had left. “Hell, he’s probably down there eating huckleberries,” the crew would joke to one another, and before long they nicknamed me Huckleberry. It was weird to get the same nickname from both ends of the spectrum—hippies and rednecks, but then those stereotype labels are just titles too.

December 10 was my last day of work. “What the hell do you mean, you’re not working today?” the foreman growled when he came to find me after I hadn’t responded to the wake-up call.

“Sorry,” I said. “I never work on my birthday.”

“Like hell you don’t,” he raged. “You work, or you’re fired!”

I have my principles. So I was fired. I had completed twenty-three successful revolutions around the sun, and that alone was cause for celebration. Having been born on the exact hour, day and year that all the countries of the world gathered to sign the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris, I wasn’t about to compromise on my right to have the day off. As luck would have it, I had made just enough money by December 10 to pay the company back for my air transport to and from their camp, as well as to buy a ferry ticket from Ketchikan to Seattle. I was Amazon-bound again.

The journey south was anything but easy. I can vividly recall the hitchhiking ordeals, like struggling to move my three large packs through downtown LA while trying to locate an on-ramp to an expressway. I could carry only two bags half a block at a time before returning for the third bag, all the time keeping all bags in sight lest they be stolen.

Mexico and Guatemala proved even more challenging. By the time I reached the border of Honduras I was so sick and dehydrated from amoebic dysentery that I became unconscious on the roadside. I regained consciousness a few days later in an old woman’s adobe hut, and I recollect vigil lights burning all around me, fresh flowers, copal incense wafting its sweet perfume into the air of the mud-walled room and a statue of the Immaculate Heart of Mary looking down on me. A gathering of the devout were reciting the rosary in their native tongue over my lifeless body and the scene had the air of a wake. Like Tom Sawyer witnessing his own funeral, I was sure I had died, was on my way to heaven and witnessing my death in spirit form. Recovering Catholics never quite shed the illusions.

Good health has never been one of my strong points. I’d had polio when I was seven, spinal meningitis at age fourteen and an acute appendicitis attack a few years later, so the odds of even making it into my twenties were squarely against me. This was the fourth big strike, and I should have struck out long ago. Little did I know that plague, cholera, typhoid, three bouts of malaria, dengue and tick fever would still stalk me in later years. If there is any lesson to be learned surviving deadly illness, it is to never take life for granted … to cherish each day as a miracle, a gift. That’s why I don’t work on my birthday.

El Salvador proved to be my nemesis and turnaround point. It had taken me six months to get that far, my health was poor, and the Amazon still seemed as distant as ever. So with no real feeling of failure, I started the long journey back north, little aware of the changes that lay ahead.

I was travelling through the Sonora Desert of Mexico, just a few days south of the Texas border, when I was dropped off by my ride in an unusually rough-looking cow town. My driver had cautioned me about the dangers of this region: “Muy peligroso, señor—muchos banditos aqui!” I promptly headed out of the dangerous bandit town to spend a somewhat safer night along a quiet desert road. It was growing dark and I had hiked far, but I could still hear the drunken revelry and occasional gunshot from the cantinas even when the town was becoming little more than lantern light on the horizon.

Exhausted, I left the roadway and searched the surrounding desert for a place to set out my bedroll under the spectacular star-studded sky. The ground was strewn with rocks, boulders and prickly pear cactus pads, so it took some time to find a clear space to bed down. At long last I discovered a soft patch of earth, just the right size, beside a large saguaro cactus. Must be a bedding site for wild burros, I reasoned as I stretched out a horsehair rope around the perimeter of my sleeping area to deter prowling rattlesnakes. The rope was a gift from a Yaqui Indian elder I’d met a few days earlier. “A rattler will never cross the scent of a horse,” he assured me. The old man befriended me because he could see that, like him, I enjoyed sleeping alone out in the desert. It struck me that he might be a mystic or shaman of some sort.

I was asleep almost from the moment I lay on my back with my head below the trunk and beautiful branching arms of the saguaro. I may have slept only a few minutes or an hour, I’ll never know, before I awoke frozen in terror. Sweat was pouring from every pore of my body, my jaw was locked open and my eyes stared skyward in an unblinking gaze. I was sure my heart would seize up too. I’d never known such total terror in my life because I had no way of understanding the source. I lay there awake all night, unable to move a muscle, wet my parched tongue or scarcely blink my desert-dust dry eyes, but grasping fully the meaning of horror.

The stars slowly worked their arced path across the black velvet sky, and a large desert owl, not too distant, hooted throughout the night. Only with the first light of dawn was I able to close my parched mouth and painfully dry eyes. It was not until the first ray of sun slowly worked its way down the cactus and touched my face that I found I could move my neck. As I did so, I turned and saw that the woody base of the saguaro had been carved flat with a knife and inscribed with the name and date of a burial. Whoever’s grave I’d spent the night lying atop had an insanely powerful spirit, and I started to see things differently after that.

The rest of my return journey north was uneventful by comparison. I did spend a memorable week with a Navajo family in their Monument Valley hogan, a traditional Navajo hut of logs and earth, where I was inspired by their octagonal log architecture and closeness to the earth, but for the most part I was just wed to the road. I had grown so weary of lugging the damned kayak around for six months that when I got to British Columbia I decided to start paddling back to Alaska. I thumbed a ride to Prince Rupert, deciding that would be a safe and suitable location from which to work my way back through the Inside Passage waters.

It was raining in Prince Rupert. It almost always rains in Rupert, that soft but seemingly endless drip that descends in a fine mist for days. The sky was leaden and my energy low by the time I’d dragged all my gear and grub down to the dockside. Like the old Otis Redding song, I found myself, quite literally, “sittin’ on the dock of the bay, watching the tide roll away” when a Mama Cass-type character came strolling down the plank way. She was dressed in light cotton, a full-length floral printed dress, and she flowed down the dock like she was not of this earth. Ignoring me altogether, she stopped at the end of the pier and stood there staring at the ominous western sky. After about fifteen to twenty minutes of this strangely frozen pose, I couldn’t help but ask her if she was okay. I had once worked backstage at a Jefferson Airplane rock concert at Michigan State University where blotter acid was handed out freely to all stagehands, so I knew the stone-dead look of an overdose. No, she wasn’t tripping, she assured me, just “cloud busting.” She carried on with her self-appointed task while I remained respectfully silent.

“What are you here for?” she asked after a while, without looking away from a brightening spot in the sky.

“Setting off to kayak home to Alaska,” I responded.

“Cool,” she said, “but aren’t you going to kayak across to the Queen Charlotte Islands first?”

“Where’s that?”

“Out there where I’m busting that hole in the sky.”

Sure enough, a patch of blue was opening in the west. I grew excited. “How do you get there?” I asked.

“Paddle, if you want,” she said, “but it’s a long way out and Hecate Strait kicks up pretty fast. There’s a freighter that takes a few passengers. It’s leaving from the pier here this evening.”

“Thanks for the tip, sister,” I said and set off to inquire about ticketing.

“The name’s Stormy,” she called after me.

I stopped dead in my tracks. “You mean like Stormy in Ken Kesey’s gang?” I was stunned. Was this one of Ken Kesey’s bus-riding beatniks, one of the infamous “Merry Pranksters” immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test? But she didn’t answer. Stormy was too busy admiring her handiwork, the clouds parting like great curtains of satin in the west. I went to book passage for the opening.