Chapter II

The Eagle’s Gift

I wanted to leave Haida Gwaii from the moment I arrived. The Northland Navigation freighter pulled into the Masset dock near midnight and disembarked its half-dozen passengers amid a crowd of curious onlookers. The twice-weekly arrival appeared to be the biggest event in town, but the mood was surprisingly sombre given how few of those gathered at the dockside were actually sober.

I strolled up the pier past a series of faceless aluminum-sided buildings that lined the length of Main Street, an absurdly wide boulevard void of any shade trees, shrubs or flowers. The town, from this vantage point, bore no resemblance whatsoever to the fabled Misty Isles I’d been envisioning during my passage. The road ended abruptly—as if ordered to “halt!”—at a Canadian Forces military base, CFS Masset. I stopped under a lamppost to dig through my wallet in hopes of finding enough money to book passage back to the mainland on the return sailing. I was short; I would have to paddle.

Resigned to my misfortune, I returned down Main Street and tried to view the village from a more positive angle. The military makeover was sadly apparent, but a few turn-of-the-century wood-frame houses and some well-kept gardens were nestled in here and there among the hideous to hint of the charms of an earlier era.

I didn’t know it at the time, but Masset was once destined to be a hub of the Pacific Northwest. In the heady days before World War I, British railroad magnate Charles Hays conceived of a plan to make Prince Rupert Canada’s principal Pacific port and the terminus of his Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. Vancouver would have been little more than a backwater, while Masset was expected to become an agricultural breadbasket to feed Prince Rupert’s great metropolis, envisioned at fifty thousand. The vast lowland bog from Masset to Tlell was parcelled out for settlement and some hardy pioneers dug drainage ditches by hand to try farming the muskeg. It never worked, and Hays’s dream died a sudden death too when the visionary went down on the Titanic in 1912. My own spirits, this June night sixty years later, had sunk almost as low.

I was dog-tired after disembarking the ship, but I still had the kayak bags to deal with. I stashed them beside a road embankment near the BC Hydro office and made a hasty bed of cedar boughs under a grove of trees beside Masset Inlet. It was not a good sleep, with Saturday-night revellers racing by along the road above me and the tide rising up to my feet, so I awoke at first light to end the ordeal. Camouflaging the two kayak bags as best I could under logs and rocks, I shouldered my backpack and set off north along the road. I wanted to find a beach where I could camp for a few days while I sorted out my next move. Several kilometres later I walked into Haida Village, a long series of Indian Affairs dwellings fronting the road along Masset Inlet. A Haida man in his thirties was the only sign of life on the road this early Sunday morning. He staggered up to me, pulled out a folding knife and with glazed eyes and an unsteady bearing, introduced himself with the words: “I should slit your throat, you stinkin’ white man.” He was the first Islander to speak to me since I’d arrived, and I took this to be my official welcome.

I remained calm and left my acquaintance staring drunkenly into the void where I encountered him, working my way presumably out of harm’s way to the beach just beyond the cemetery of the village. Here, finally, was food for the spirit. A majestic sweep of sand and gravel beach stretched more than 160 kilometres along the shores of Dixon Entrance and Hecate Strait. Breakers rolled endlessly down the long reach of shoreline, roaring like bowling balls down some infinite corridor. The air was heady with oxygen and the rich aromas of salt, seaweed, seabird droppings and the occasionally fishy burp from some offshore sea lion. Across the deep cobalt blue of Dixon Entrance, the southernmost islands of Southeast Alaska shimmered in the sun. This was the Queen Charlotte Islands (QCI) I had been hoping for, and I felt a great weight lifting from me, as if someone had come along to shoulder the bags of my kayak and gear. For six months and almost 10,000 kilometres of hitching, that kayak had hung around my neck like an albatross; now I would finally get it on the water where it belonged.

I was feeling much more positive about the Islands now, and as if to bolster my spirits even more, the following afternoon the man who had threatened me was all smiles as I walked back through the village. It was as if he had been awaiting my return, though he seemed to recall nothing of our first encounter. He pointed to a doorway where an old Haida woman was looking at me. “She’s been expecting you to join her for lunch,” the man said pleasantly.

“What?” I asked in utter astonishment. “Yesterday morning you wanted to slit my throat and now …” He acted as if he hadn’t heard me and went on his way. The old woman beckoned me inside.

A traditional Haida feast had been set out by the woman’s grandchildren. There was barbecued salmon, fried halibut, razor clam fritters, steamed Dungeness crab, herring spawn on kelp, dried oolichan and oolichan grease, octopus, abalone, seal meat, wild berries, boiled potatoes and bannock. I’d never seen a spread like this in my life. You couldn’t order this in any restaurant in the world, and even if you could, few could afford it.

The woman’s name was Eliza Abrahams. She was the oldest living Haida, and according to accounts I heard later, she was the most traditional. Eliza spoke little English but was bright and fluent in her own tongue. The two of us dined together and laughed and enjoyed each other’s company even though there was little common language between us. After we ate, far too much, she had her family go into her dresser drawers to bring out all of her button blankets and family heirloom regalia to set on my lap. “What’s happening here?” I finally felt compelled to ask one of Eliza’s attendants, even though I ran the risk of appearing rude.

Always immersed in her culture, Eliza Abrahams is seen here weaving a cedar bark hat in 1976. Three years earlier, she was the first person on Haida Gwaii to befriend me, welcome me into her home and serve me a lavish Haida lunch. Had it not been for the generosity and hospitality of this oldest and most traditional Haida Nonnie I might have left Haida Gwaii a few days after my arrival. Ulli Steltzer, 1976, Haida Gwaii Museum At Kay’llnagaay, Skidegate, BC, Canada

“She’s been waiting a long time to see you,” came the bewildering answer.

I had never really believed in destiny. At least, my lifelong liberal education had taught me not to. I always wanted to think that I made my own choices in life; for better or worse, I did what I truly wanted. If I wasn’t exactly always in control of a situation, neither was I merely subject to the whims of fate. I believed this. I wanted to believe this. I needed to believe this. But my little lunch with Eliza made me start to question it all.

The pace quickened now; I was embarking on a journey that would mould me and hold me in its spell for decades to come. I returned to the place I had stashed my collapsible kayak, retrieved the two big bags and started hitchhiking south. Before long I was offered a ride from Masset along the seventy-mile length of the Islands’ only highway to Queen Charlotte City, a misnomer if ever there was one. This small settlement of only a few hundred souls, spread out along the north shore of Skidegate Inlet, had become the preferred gathering place for alternative-lifestyle youth arriving from the mainland. It was Canada’s Ellis Island; all it needed now was an upright eagle or raven statue bearing a torch: “Send me your dispossessed, your stoned and your penniless.” For $65 you could buy a home site on “Hippie Hill” from John Wood, in all probability the world’s only real estate developer who never charged a penny more for the land than he had paid for it. Or you could join other refugees from the North American middle-class suburban dream and squat on Haida land—or Crown land; it depended on how you looked at it. In either case, the issue was rarely raised in the early ’70s.

Ron Suza and Pete Townson were two of the handful of “heads” who chose to settle on remote Burnaby Island at the southern end of the Queen Charlotte Archipelago. They hadn’t been there long, however, before their cabin burned down and they found themselves back in Queen Charlotte City, the night I arrived, performing at their own benefit concert. It was a great event with a wealth of local talent, a throbbing sense of community spirit and enough cannabis smoke in the dark dance hall to stone you on entry.

Somehow in the dark and the din I made a new friend, Glenn Naylor, a British bloke who had the best of both worlds—a log cabin along Burnaby Narrows and a house on Hippie Hill. He too was a kayaker and was planning to paddle back to his cabin on Burnaby Island in the next few days. “Why don’t you join me?” he offered. “You can crash at my place on the Hill until we go.” Great good fortune was smiling at last.

It was a beautiful night up on the Hill, as the hippie homeowners called it, and I rolled out my sleeping bag on Glenn’s porch to drink in the sweet summer air. By 2:00 a.m., the musicians had moved from the community hall to a house on the far side of the Hill where a great musical jam was ensuing. The sounds sweeping over the land were in many respects typical of the era: the rich unplugged sound of acoustic guitars, the wail of harmonicas, the flutter of flute and the steady rhythm of conga drums. Only the drumming stood out as something out of the ordinary. The rhythm was drawn from somewhere deeper than the stoned groove everyone else was jamming to. It seemed to come from the land itself. The trees, the rocks, the cedar-plank floor I slept on—all reverberated that pulse. Although I did not get a glimpse through the trees of the musicians that night, I felt connected in spirit to that “talking drum.”

“Who was on the conga last night?” I casually asked Glenn over breakfast porridge.

“Oh, that must have been Gary Edenshaw,” he answered; “He’s a Haida from Skidegate.” Ten years later, long after my life and Gary’s had become inextricably linked, the Haida elders deliberated long and hard to honour him with a new Haida name. His uncle Percy Williams had bestowed upon him the name Ghindigin, the “Questioning One,” but somehow he’d outgrown that. The new name that better suited him, the elders decided at length, was Guujaaw, Haida for “drum.” I could have told them that.

It was 8:00 a.m., June 21, 1973, when Glenn Naylor and I launched our kayaks from the beach in Skidegate Village, the Haida community just five kilometres east of Queen Charlotte City. I recall the time exactly not because it felt like some historic moment, but because it was the first time in eight months I wasn’t bearing the weight of the kayak … it was bearing mine. I felt wondrously weightless and free as we rode the ebb tide out Skidegate Inlet and felt the great swells of Hecate Strait. We had just enough clearance to glide over the long sandy spit that reaches out from the northeast tip of Moresby Island and gives this second-largest island in the archipelago the name of its only permanent community: Sandspit.

We were bucking tide now. This region has the greatest tidal fluctuation on the Canadian Pacific coast, and it wasn’t worth the effort to push on against it. Of course, it pales in comparison to the Bay of Fundy’s reported fifty-foot fluctuation in the Atlantic, but an eighteen-foot rise and drop in the water level every six hours is nothing to toy with either. We sat out the flood tide at Gray Bay.

It was late evening before the currents were running in our favour again, but there was still plenty of daylight to travel. This was, after all, the longest day of the year, and in this northern latitude, there would be light until 11:00 p.m. We managed to reach Cumshewa Rocks by sunset; it was an offshore seabird island with hundreds of nesting gulls. The tide was very low so Glenn and I gathered gooseneck barnacles and a few gull eggs for our dinner. When goosenecks are steamed, the shell and outer sheath of the barnacle slips off and a tasty morsel of meat melts in the mouth. Gooseneck barnacles have a rich flavour, a bit like crab, to which they are related. They are so delectable it’s surprising they’ve never worked their way onto epicurean menus.

I was told the Haida name Cumshewa means “rich at the mouth of the inlet,” and we certainly felt as rich as kings dining with the gulls on the most dainty of delicacies that night while the sun set over the long, glassy, smooth reach of Cumshewa Inlet. It was the perfect summer solstice party.

We slept out the few hours of darkness under the stars on barren rock, washed smooth from eons of pounding waves. Hundreds of gulls sounded our alarm clock at first light; there was to be no sleeping in unless we wanted to be whitewashed in gull droppings. Glenn headed south to a logging camp on Thurston Harbour, where he wanted to check on his mail, while I detoured up Cumshewa Inlet to view one of the old abandoned Haida village sites I had seen on my nautical chart. We agreed to meet that night at a place on the chart named Vertical Point.

Cumshewa absorbed me that morning like a deep dream. It was otherworldly stepping into the moss-hushed forest of that ancient village site. Shafts of sunlight pierced the morning mist and softly illuminated the remains of century-old totems. Great heraldic beasts with large ovoid eyes and broad, raised eyebrows stared in bewilderment as if forever frozen in the surprise of their own demise. Cumshewa, like many Haida villages, had been decimated and abandoned following a devastating smallpox epidemic in 1862–63. In one horrible summer nearly three-quarters of the Haida population succumbed to the deadly disease. The real tragedy is that it could have been averted.

American gold-rushers flocking from San Francisco to Victoria, British Columbia from around 1858 brought with them the horrible scourge. Vaccine for smallpox was available at that time, and all white settlers and their Chinese servants in Victoria were immunized. There was no recorded attempt to vaccinate the large Indigenous population residing in Victoria or anywhere else along the coast. When one looks at the history of Indian wars, relocations, ethnocide and genocide against the First Peoples in North America, it is difficult to excuse this as an oversight. An even more sinister scenario is documented in Tom Swanky’s academic book The True Story of Canada’s War of Extermination on the Pacific. According to the author, Victoria’s famous Dr. John Helmcken, while pretending to vaccinate the Indigenous peoples, was actually inoculating them with smallpox at the urging of Governor Sir James Douglas.

A cargo cult had developed around the European trading centres along the Northwest Coast and in the 1860s, a century after first contact, the principal trade centre was Victoria. In addition to the Songhees Village of the Coast Salish peoples located in Victoria Harbour, Kwakiutl and Haida encampments were set up for trade near what is now Victoria’s cruise ship terminal. It was not uncommon for Northwest Coast Indigenous nations to hold rights to land through marriage, peace agreement or some other arrangement in the midst of another Indigenous nation’s traditional territory. Such was the situation for the Haida settlement located near the entrance to Victoria Harbour in the fateful year 1862.

It may be our feeble attempt to fathom the unfathomable, but very often the great tragedies that befall humanity are reduced to simple tales. We are told that the great fire that burned down Chicago started when Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicked over a lantern during milking, and that the maiden voyage sinking of the Titanic was God’s punishment for the ship having been christened the “unsinkable.” So too, the smallpox scourge that decimated the North Pacific coast nations has been reduced to a mere tale.

According to the “official” story, Sir James Douglas ordered the Haida settlement to be cleared out of Victoria, at gunpoint if necessary, to “protect” them from the spread of smallpox. The Haida, for centuries, had been considered the lords of the coast and refused to allow themselves to be humiliated through such a disgraceful departure. Mustering their courage, the Haida regrouped their canoes offshore and returned in war formation to face the cannons. It was a display of pride more than any other, but it became a cornerstone of the smallpox tale. The Haida stayed just long enough to contract the deadly illness, so the story goes, and as they paddled up the coast they stopped at every village to boast of their daring deed and in so doing spread the smallpox. Cumshewa was one of the villages the death canoes stopped at.

A great sadness hung over Cumshewa at the time of my visit; it was as if the world had closed in on itself. Human skulls, still working their way to the surface from burial mounds blanketed under thick moss, told of the magnitude and swiftness of the disaster that befell this once thriving community so “rich at the mouth of the inlet.”

I fell asleep in the sun on a mossy promontory of land where there was evidence of otters frolicking and cracking open crabs. It would be wrong to say that I fell into a deep dream; it was more a trance, an altered state, an almost out-of-body experience in which the village came fully alive again. Children laughed and squealed with delight as they bounded barefoot over the gravel beach to help haul in halibut from returning fishing parties. Women strung strands of kelp with herring roe attached to dry in the sun atop cedar drying racks. Smoke curled from each of the sixteen longhouses and countless smokehouses so that the air was permeated with the rich aromas of alder-smoked clams and spring salmon, boiling crab and other foods fresh from the sea. Somewhere down the beach the sound of wood being slowly chipped away told of a canoe being fashioned from a great cedar log. Nearby, a master carver was putting the finishing touches on a huge ceremonial pole to proudly proclaim the lineage of his family for all the world to see.

It was late morning before I paddled away from the ghost village and crossed Cumshewa Inlet to Louise Island. Huge beds of bull kelp, stretching far offshore, indicated that I was running with the tide. Sea lions, cormorants and pigeon guillemots bobbed in the tide rips running strong off Skedans Point. Something felt totally different, yet strangely familiar, as I paddled through the breaking tide rips. I was used to river running where the current is swift but waves are stationary, or lake travel where the waves are moving through stationary water. Now I had to cope with both conditions simultaneously. The sea here could go from calm to raging tide rips in a matter of minutes and one had to be alert, to live and learn, or risk not living long.

A perfect peninsula juts out from the eastern shores of Louise Island and embraces two superb landing beaches. This stunning setting was the site of one of the greatest strongholds and most celebrated Haida villages. Those born at Koona, also known as Skedans, were truly masters of their universe, at least until the epidemic hit. Now, like neighbouring Cumshewa village to the north and Tanu to the south, Koona is but a hollow, brittle shell of its former glory. Most of its monuments in cedar today grace the museum lobbies of the world, while a few forgotten grizzly and eagle mortuary poles lean dangerously or recline on the ground sprouting flowers for their own funerals.

What made the tragedy that befell Skedans especially poignant this June day in 1973 was to witness the sacred resting place of its one-time inhabitants being desecrated through logging. An aluminum-sided trailer had been skidded up the beach and into the village site from a barge, and a bulldozer was being used to haul logs down from the hillside. It was a small gyppo operation run by a married couple and a few hired hands, but the impact on the site was massive. How could a major archaeological site be treated in this way, I wondered. Wouldn’t the Haida believe their ancestral spirits would be outraged? The answer to both of my questions came some days later.

If there was a silver lining in the dark cloud that hung over the Skedans site that day, it was the warmth and genuine hospitality of the couple that held the logging concession. They invited me in for dinner and sent me on my way with fresh homemade bread, still hot from the oven. But paddling south to my rendezvous with Glenn at Vertical Point, I was saddened to see in the distance the massive clear-cut scars and associated landslides on Talunkwan Island. Little could I have known what a rallying point this mangled island would become in my future endeavours.

We found ourselves stormbound on Vertical Point the next morning. A roaring southeaster had turned Hecate Strait into a fury of white froth and mountainous waves. Glenn and I hunkered down and battened the hatches in a small cabin built on the Point by Benita Sanders, an acclaimed artist residing in Queen Charlotte City. Pots of wild mint tea and a few select books from Benita’s little library helped ease the slow passage of the day.

Though the wind had abated the following morning, the seas were anything but calm. Glenn felt confident that the worst of the storm was over and that we should push on. A certain lady friend he was anxious to see again at his Burnaby Narrows cabin may well have been clouding his judgment. We paddled out of the protected little cove fronting Benita’s cabin and were engulfed by the sea.

The swells were enormous, but at least they weren’t breaking. Only on the crests of the waves could Glenn and I see each other, though we were never more than fifty metres apart in our separate kayaks. Dropping back into the wave trough after topping each crest was like being consumed, swallowed up by the sea. Huge walls of steel-grey water obscured any hint of land. It was as if the leaden sky itself had fallen and sunk into the sea, still writhing in the depths from the wrath of the storm. Humbling as the experience was, it was also exhilarating.

Entering the sheltered, calm waters of Klue Passage and the serenity of Tanu Island after the harrowing high seas was to know the true meaning of salvation. Could there be a more serene setting in the world than the moss-hushed silence of Tanu? Tanu in Haida translates to “where the eel grass grows,” and this ancient village site not only supported an amazing diversity of marine life, it once rivalled any culture in the world for artistic expression. Pole carvers from Tanu were sought after up and down the coast for their brilliant designs and masterful carvings. One Tanu pole is the subject of a painting by Emily Carr titled Weeping Woman of Tanu (1928) and depicts the tale of Frog Woman shedding tears that turned into frogs after the brutal burning of her children. Today, the pole has been cut into sections and is displayed in the glass rotunda of the Royal BC Museum, but the spirit of what the master carver captured is still very much a part of Tanu.

I spent hours wandering among the massive longhouse ruins being reclaimed by the forest. A few superbly crafted corner posts still stood, but the roofs of the longhouses had long ago collapsed. Beams smothered in a dozen species of moss spanned the ground pits, some of which were twenty-five metres across. It must have been a Herculean endeavour to construct one of these massive multiple family dwellings. I knew from my anthropology courses that eight or more nuclear families of the same clan all lived under the same roof, and forty to fifty people would have resided in the largest of these houses. Living within the clan house brought with it a strict social code based on rank. The clan chief resided along the back wall farthest from the entranceway, which was often a carved tunnel-like passage through the bottom carved figure of the house’s frontal pole. Only one person at a time could enter through this portal and they had to bend over to do so. This allowed the house to be easily defended, even by women and children, as intruders could be clubbed in the back of the head one at a time as they entered. It is said the Haida positioned their slaves closest to the entranceway to further foil attack. The cry of a stabbed slave at night was all the security alarm system a household needed. Then again, if the slave was from a neighbouring tribe and recognized common language in the attackers, he might become a liability more than an asset.

Everyone cooked on a central hearth in the middle and lowest level of the two- to three-tiered floor and found some semblance of privacy along the upper sleeping levels where bent cedar storage boxes and blankets divided the room into private quarters. The Haida longhouse was seen as a living being as well as a container of souls; it had skin (the planks forming the walls) and bones (the rafters and central supports). The heart was the central hearth and a mouth for exhalation was symbolized by the smoke hole. Two distinctive styles to Haida longhouses distinguished them from all others on the Northwest Coast—the two-beamed and the classic six-beamed. These houses displayed great architectural ingenuity designed to meet specific and demanding environmental conditions. Perched atop excavated house pits, the Haida longhouse was amazingly roomy inside while keeping a low profile outside, a necessary condition for the gale-force winds and the occasional tsunamis they were subjected to. To protect against frequent violent earthquakes the Haida, like the Japanese, designed their homes to have no inflexible parts. Every piece of the structure had free movement within the grooves and notches that held it all together. A house could also be easily dismantled and moved to another location, yet another way of coping with changing food supply or security needs. To better cope with enemy raids and warfare, the houses were often so close together that one could not easily walk between them. This fortress effect required defence only on the farthest flanks to prevent war parties arriving by canoes from sneaking behind.

We left the ruins of Tanu to slowly work their way back into the earth and paddled into the most spectacular coastal wilderness I had ever seen. All the way down Darwin Sound and into Juan Perez Sound I couldn’t help but marvel at the astonishing density of eagle nests, the profusion of seabirds, falcons and marine mammals, and the stunning biodiversity of the tidal zone. The forest itself was the greatest feature, a wonderfully untouched ecosystem with age classes of trees ranging from a few months to several thousand years old. The ancient cedars, with their multiple dead tops bleached a lustrous silver grey, spoke of the antiquity of these post-ice age forests. Like the greying hairs of an old wise one, they spoke to the need for reverence and respect, something noticeably lacking in Northwest Coast forestry practices.

It took nearly a week to reach Burnaby Narrows and the small community of back-to-the-landers who resided there. Glenn’s dovetail-notched log cabin stood boldly on a high gravel bench just above all but the highest of tides. Only a few times a year did he have to move all of his belongings and himself to the upper loft while the tide inundated the house, he told me.

It is the rush of tides between Juan Perez Sound in the north and Skincuttle Inlet in the south that has always made Burnaby Narrows a choice place to live. As the tide ebbs, the Narrows present one of the richest and most spectacular life zones on the Pacific coast when thousands of miniature geysers squirt skyward as butter clams, little necks, geoducks, horse clams and cockles expel water from their siphons. At low tide the seabed becomes a kaleidoscope of colour with bat stars in every hue of the rainbow, sun stars in lavender and red, bright-red blood stars, and ochre, orange and purple pisaster starfish. Along the shoreline of the Narrows one can see evidence of thousands of years of Haida occupation represented by deep shell middens. The only trace of the village that once occupied this important site are these shell disposal sites and a small grove of crabapple trees growing in a clearing not far from Glenn’s cabin.

A great party was thrown at the cabin for our arrival and it was there I met Axel Waldhouse, an Eastern European immigrant to Canada who wanted to join me on my kayak journey south to Ninstints, a village on remote S’Gang Gwaay Llanagaay (Red Cod Island). It is the most intact ancient village on the entire Northwest Coast and I very much wanted to go there.

It was a wild and somewhat harrowing experience to paddle around the southern end of the Queen Charlotte Archipelago several days later and out to the exposed west coast with the highest recorded winds and wave action in all of Canada. Every feature of the landscape here reflected the fury of this coast: the wild, wind-sculptured trees, the flotsam and jetsam hurled deep into the forest and the splash zone of the rocky shore, void of vegetation ten to twenty metres above the tidal level. What people would have chosen this small, storm-lashed fortress for their home, we wondered as we paddled the huge Pacific swells toward the isolated island.

Axel and I were less than a kilometre from the island and lost in our own thoughts when something huge surfaced behind us as we paddled. A great black island of flesh rose from the depths, exhaled with a blast of air that showered us in a fine mist, and then rolled forward with one, two, three … far too many dorsal fins! For weeks I had hoped to get a glimpse of an orca, a minke, a fin, humpback or grey whale, but what was this? Scannah, the legendary five-finned killer whale, was a monster of myth, or so I’d been told.

Still unnerved and a bit spooked by the encounter we’d had offshore, Axel and I arrived on the deserted island. The haunting eyes of a dozen mortuary poles lining the beach stared at us unblinking as we hauled the double kayak up an ancient canoe launch cleared of large rocks. Those eyes continued to follow us in an eerie gaze as we moved reverently about the site.

Ninstints in 1973 was awe-inspiring. It was like coming upon Angkor Wat in Cambodia or Tikal in Guatemala before the archaeologists arrived to cut back the jungles. Unlike museum display poles with their chemically treated wood in climate-controlled confines, nature made it beautifully clear these poles belonged here. The trees that embraced them, the roots that split them and the stunning arrangements of ferns, flowers, salal and moss that adorned them—all made it apparent that the forest was reclaiming a part of itself.

Ninstints boasts the world’s largest display of totem poles in their original setting, and although the site hadn’t yet been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Site, it seemed just a matter of time before it would become known to the world. What makes this fortress island such a world-class attraction is not the poles but the wilderness in which they are set. A visitor can look out in any direction and see the same unspoiled scenes the inhabitants of the island saw for thousands of years—a setting hauntingly alive and still echoing with the spirits and drum songs of those who lived here more than a century ago. The legendary Haida transformations from human to animal form and back again seemed not only plausible here, they appeared to occur before our eyes.

If there is any sense of conventional reality on Haida Gwaii, it is blurred at the best of times. The merciless moisture and relentless fog of the west coast creeps in so often from the surrounding seas to obscure the headlands and highlands that the landscape itself becomes a phantom, an ever-changing figment of the imagination. If we in our cynical, scientific age can find power and spirit afoot here, one can only imagine the effects it had on the Haida, a people who did not deny or cast aspersions on the supernatural. To them, the great supernatural beasts and transformed forces that rule these isles are real, like Kostan, the giant crab that can crush a fifty-foot Haida freight canoe with a single claw, or Goghits, humans that revert to a state of primal wild being and hide in haunting forests of towering trees.

One evening while Axel was slowly cooking supper over an open fire, I hiked across the island to view the sunset on the wild west side. It was a savage scene. Wind-tortured trees gripped bare rock headlands where waves, built up over the world’s largest ocean, exploded like bombs and roared their defiance at an island that had the audacity to interrupt their passage. Eagles cried in the dying light of day as they circled cliffs covered in eerie lichen that glowed blood red as if the setting sun had suddenly dissolved and been cast like wet watercolours across the granite faces. Racing against darkness to return to camp, I was surprised to see Axel approaching me on the trail. He must have been worried, I thought, and I called out to him, “Hi Axel, I’m fine. I was just …” He was no longer there; a raven cried and flew off into the forest canopy. I raced back to camp to find Axel asleep beside the fire.

It was in this weirdly affected state that Axel and I left Red Cod Island and began the long journey back to Burnaby Narrows. There we parted ways. I was kayaking on my own now and would be for months to come. I crossed Juan Perez Sound to Hotspring Island, a paradise on earth if there ever was one. I lingered a few extra days to soak in the soothing geothermal springs set in natural rock grottos overlooking the spectacular islands and distant mountains that rimmed the sound. I was totally alone, but there was life everywhere: soaring eagles, barking seals, a gaggle of squawking gulls. Clever ravens cracked and opened clams by repeatedly dropping them from great heights onto the rocky shore and hyper little hummingbirds buzz-bombed the pool I soaked in as they darted from flower to flower, sipping the sweet nectars of red columbine and multi-hued foxglove flourishing early in the season thanks to the geothermal warmth. Every so often one needs moments of pure bliss.

Rather than return north through the protected waters of Darwin Sound, as Glenn and I had done on our southbound journey, I decided to paddle the more exposed east coast around Lyell Island. When the tide turned against me at midday I pulled into shore to wait out the ebb at a place marked on my chart as Windy Bay. Nothing was particularly outstanding about this bay compared to countless others I had stopped to explore along the way—at least, not until I set foot in the forest.

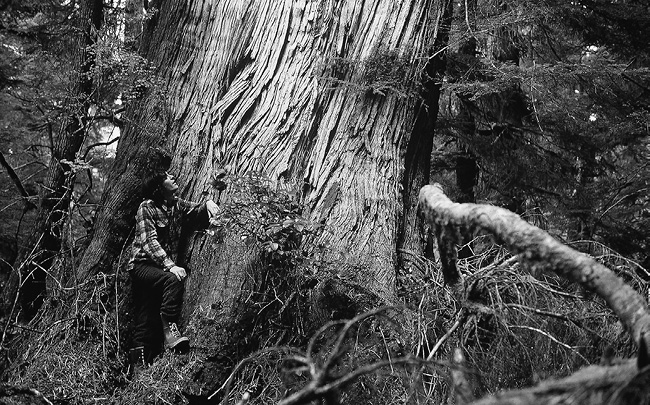

Standing beside a massive western red cedar at Windy Bay in 1973, I was awed by the majesty and antiquity of South Moresby’s temperate rainforests. Richard Krieger photo

Here was the temperate rainforest of fairy tales, an enchanting garden of massive moss-draped trees: western red cedars, yellow cypress, Sitka spruce and western hemlock with bases three to six metres in diameter. Fifty metres overhead, the crowns of these conifers formed a cathedral dome where shafts of sunlight penetrated the mist and the sea breeze sent a perpetual rain of needles shimmering to the ground. There was little, if any, understorey here; instead, a deep, luxurious mantle of moss in subtle shades of green carpeted the ground and a few fallen forest giants. Windy Creek flowed through this valley like a living artery; its crystal-clear waters babbled and flowed over clean spawning gravels and formed back eddies behind fallen trees where several species of salmon fry found shelter. Eagles perched in trees overhead eagerly awaited the return of the salmon migration, and black bear trails, already centuries old before I walked them, meandered along the stream bank.

Windy Creek flows through the moss-smothered forests of Lyell Island like a living artery.

I found myself mesmerized, listening in reverence to the calls of the varied thrush and Pacific wren as if they were a Gregorian chant in a great cathedral. It was hours before I returned to the beach and began gathering firewood to cook some bannock for dinner. I still had another hour or two before the tide would flood again and I could resume my journey north.

I had combed the entire length of the beach for firewood and was in the process of flipping the last of the bannock in the pan when an eagle landed in a tree behind me and started calling relentlessly for its mate. I scanned the skies for some time in vain, but soon discovered that lying on the beach less than ten metres from my fire site was a dead eagle. I was overwhelmed. The eagle’s body still felt warm so it couldn’t have been dead for long. I wondered how I could have missed this transpiring in the time I was on the beach.

I took the eagle carcass in my hands and was astonished at the size of the wingspan. Knowing that the Queen Charlotte Islands’ museum was nearing completion in Skidegate and realizing that I was just a few days’ paddle from returning there, I decided to try saving the carcass so it could be used as a stuffed museum specimen. It would be a shame, I reasoned, to kill an eagle for this purpose when this one was so perfectly intact.

I made a small offering to the eagle’s spirit, then carefully cut open and disembowelled the body cavity and restuffed it with damp moss. I had learned to keep fish fresh for some time with this same procedure in Alaska, so I felt confident the carcass would not spoil before I reached Skidegate.

The eagle’s mate was still crying from the treetop when I loaded up the carcass in the stern of my kayak and paddled out of the bay. The sea was flat calm without a breath of wind that evening, and I offered up a prayer to the eagle’s spirit to give my kayak the wings of an eagle. A fresh, steady breeze came up out of the southeast and I figured I could make Vertical Point before dark if I made use of my sail. A white bedsheet I had used for bedding throughout my Central American sojourn was now doubling as a square-rigged sail whenever the winds were favourable. I had drawn a stylized Haida eagle head on the sheet with a waterproof felt pen some weeks earlier, so it seemed fitting that moment to hoist sail.

Ten nautical miles away and out of sight to me, Percy Williams, the chief councillor of Skidegate, had set anchor for the night on the north side of Vertical Point. Wanting to stretch his legs after a long day of salmon trolling, he rowed ashore in his skiff and hiked across the narrow neck of land to hunt for deer. Scanning the beach unsuccessfully, he found himself gazing out to sea. He wasn’t looking for anything in particular; it was just a built-in Haida instinct that had helped his ancestors survive more than twelve thousand years on a coast where war parties arrived by sea.

What Percy had seen that evening completely baffled him, as he later recounted to me. It was not a war party, but a great eagle flying low over the water, its wings wet and glistening in the sun, and it was coming straight toward him. Although he had been a seaman all his life, Percy had never before seen a kayak, and the wing-like movement of the paddle blades catching the last rays of the setting sun and the large white, sheet sail depicting the head of an eagle had totally mystified him.

The sun had already set before I made my landing on the beach and began hauling my gear up above the high-tide line to make camp for the night. There in the twilight, amid the silver-grey beach logs, I was surprised to see a Haida man with a sweater as weathered and hair as grey as the old cedar log upon which he sat. People behave oddly when they’ve been out of the social loop for a while, so instead of the customary courteous hello, I said nothing. But I immediately thought, I want to show this man my eagle. I took the carcass from the kayak stern and carried it up the beach, holding it out with both arms proudly.

The old man stood, startled, and took a few steps back, all the while watching me intently. “Why do you bring me this eagle?” he said cautiously.

“Because there aren’t many left,” I responded without thinking.

For me, growing up in Michigan where DDT poisoning and habitat loss had decimated the North American bald eagle population, the statement was true. For Percy Williams, growing up in Skidegate where eagles on the beach are as common as pigeons in a city park, my statement was bewildering. Neither of us said anything further for some time, until finally we sat on a beach log and casually started talking about my journey and how extraordinary I found the Haida Islands. I expressed deep concern about the clear-cut logging I saw working its way progressively south and I lamented what was happening at Skedans. Skedans, it turned out, was the ancestral village of Percy’s mother, and as Haida trace their clan lineage matrilineally, it was his village as well. The logging concession had been sold, he told me, because Skidegate needed funds to build a new basketball court and community recreation facility for their youth. “We’ll never do that to a village site again,” Percy said, though he never let on that he was both a hereditary and elected chief of Skidegate. For me, our impromptu encounter was a moment in time soon forgotten; for Percy it proved profound, and would influence the course of Haida history.

ReDiscovery: The Eagle’s Gift film promotion featured Gerald Amos wearing Rediscovery regalia made from the same eagle carcass I had found at Windy Bay in 1973. Richard Krieger photo

The eagle carcass never did make it to the Queen Charlotte Islands’ museum. The museum society didn’t want it: Ottawa was supplying all their bird specimens fully stuffed and mounted. The Windy Bay eagle found its way to a storage freezer in Victoria’s Royal BC Museum, only to be returned to Haida Gwaii seven years later as part of the regalia donated to the Haida Gwaii Rediscovery Camp. I had never shared the eagle story with anyone so I was dumbfounded when Peter Prince, an independent filmmaker from Victoria (who now lives on Salt Spring Island), produced an award-winning documentary on Rediscovery that he titled ReDiscovery: The Eagle’s Gift. The promotional poster featured Gerald Amos, a Haida participant on Rediscovery, wearing the wings and body feathers of that same Windy Bay eagle.

It was then that I came to the realization that I was merely a player on the Haida Gwaii stage; the best I could do was bear witness to my own unaccountable involvement.