Chapter III

Drawing the Line

At one time or another we all adhere to boundaries, borders and lines in our lives. They help us establish our territories, define our relationships, set sight on our goals, or just bring some semblance of order to a world that all too often appears chaotic. Somehow, though, it’s not adhering to pre-existing boundaries but creating new ones, or defying established ones, that define us most. Heroes and fools, geniuses and social misfits know what it’s like to do so. A person’s actions can create a boundary just as their other actions can challenge and break a boundary down. My involvement with South Moresby and Rediscovery would soon put me at both ends of that spectrum, though it would confound me how I got there.

Arriving back in Skidegate in July 1973 after my kayak trip through South Moresby left me in a bit of a quandary and had me asking myself, “What exactly am I doing on the Queen Charlotte Islands?” I decided to press on back to my cabin in Alaska, my original goal when Stormy had detoured me with her cloud-busting trick back in Prince Rupert. I needn’t return to the mainland to do so, I reasoned; I could paddle back to Alaska across Dixon Entrance. If the Haida could make this sixty-kilometre crossing in their dugout canoes, surely I could do the same in my kayak, I thought with all the self-assurance and blissful ignorance of a twenty-three-year-old convinced of his immortality.

Rather than deal with the long, shelterless northeast shores of Graham Island, the largest of the 150 Haida Isles, and treacherous Rose Spit, I decided to head north through Masset Inlet from Port Clements, a small logging-based community in the heart of Graham Island. According to Haida legend, this passage was made possible by Taaw, the younger brother of a larger hill by the same name. These hills, it is said, once resided side by side in the centre of Graham Island until the two brothers had a dispute over who was eating too much of the food. One night the younger Taaw left his sibling in a rage and stomped out across the bogs in the dark. His aimless wanderings carved out what is now Masset Inlet, an unusual body of water that extends from a wide bay near Port Clements fifty kilometres down a long, narrow channel to Old Massett at the mouth of the inlet. When Taaw reached the shores of Dixon Entrance he continued wandering east along the beach until he came to the mouth of the Hiellen River. Taaw looked out over the twenty kilometres of glistening white sand that forms the Great North Beach and knew he’d found his new home. Here was food in abundance: razor clams, cockles, weathervane scallops and Dungeness crabs that washed in on the big storm tides and piled up like windrows along the beach.

From the top of Taaw (Tow Hill) today, one can look out from this ancient volcanic basalt plug and view Masset Inlet to the west and Rose Spit to the east. Naikoon, “the nose,” was the name the Haida gave this great sandspit that extends out into Dixon Entrance and marks the boundary with Hecate Strait. East coast erosion from the prevailing southeast winds is depositing sand at the tip of Rose Spit so fast that the land is growing two to three kilometres ahead of the colonizing vegetation.

The Great North Beach is noted for another reason—it is the sacred site of Haida creation. It was here, legend tells us, that a bored but ever curious Raven heard sounds emanating from a cockleshell on the beach. Prying open the strange bivalve, Raven inadvertently released the first humans—the Haida.

I was thankful to Taaw for the passage he had created as I raced out of Masset Inlet in my kayak on the strong ebb tide that midsummer morning. It seemed amusing that an early European explorer had once sailed to the head of this inlet thinking he had found the fabled passage to the Orient.

I stopped briefly at Yan, a lovely ancient village site opposite Old Massett at the mouth of Masset Inlet, and then proceeded out into the open waters of Dixon Entrance. I could see that a storm was beginning to brew but foolishly pressed on toward Langara Island. A pod of feeding killer whales surfaced from directly below me, giving me quite a start. The sea grew dark and threatening; steep breaking waves compounded the huge swells rolling in off the open Pacific and the wind built to gale force. There were no boats in sight and no apparent landing beaches; only kayak-crunching waves exploding on fortress-like rocky headlands. I needed to find shelter, fast. The orcas appeared again, nearer to shore, and one of them breached in a spectacular display, which couldn’t help but catch my eye even amid the storm. It was a good thing I looked, for directly behind the breaching whale I spotted a narrow opening into a small bight. Riding the breaking swell, I shot through the passage into a perfectly calm harbour where a dozen salmon trawlers were tied up at a floating dock. The place was called Seven Mile and it was a harbour day, with the entire fleet sitting out the storm. All eyes turned on me in astonishment as I paddled my seventeen-foot canvas kayak in out of the storm. “It’s a good thing the Lord looks after fools,” was the only comment I elicited from a fleet of fishermen looking down on their first kayak sighting in these waters.

The next day dawned bright and cheery, and if the sea wasn’t exactly calm, neither was it life-threatening. I set out at dawn and paddled westward along with the trawlers. Virago Sound acts like a great funnel, drawing boats into Naden Harbour, another important Haida heritage site. Sitting on the western point of land that constricts the passage to Naden Harbour is the strategically positioned but serene setting of Kung. The ancient village site of Kung gave me the feeling of coming in out of the storm; it probably gave its ancient inhabitants the same sense of security.

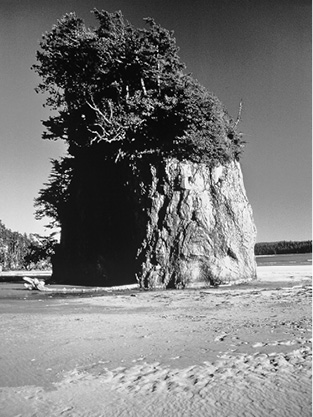

The following day I pressed westward and camped at Pillar Bay, where a stunning conglomerate of rock pillar stands proud of the water a hundred metres offshore at high tide. Some say a shaman’s bones rest atop the thirty-five-metre pillar. It would certainly take superhuman powers to place a corpse or the bones of the deceased there.

Working my way up the east coast of Langara Island, I kept a close eye on the weather and the southernmost of the Alaskan islands, barely visible across the sixty-kilometre expanse of Dixon Entrance. A lighthouse stood on Langara Point and another across the entrance at Cape Muzon, Prince of Wales Island, Alaska. My plan, which seems absurd in retrospect, was to depart Langara Point at first light, paddle all day and through the night using both light stations as beacons to guide me in the dark. I had calculated that I could paddle thirty kilometres a day, meaning I should be able to reach Alaskan shores by dawn the next morning. What I had not accounted for was fog that, more often than not, obscures both light beacons, currents running east and west through the passage—which can pull a kayak completely off course—and the prevailing southeasterly wind. The wind in particular would prove my nemesis.

The Haida, I learned later, never set off for Alaska from Langara Island, but from Tow Hill on North Beach so that if the prevailing wind, a southeaster, came up, they still had a chance of reaching Dall Island in Alaska before being blown out into the open Pacific. My route would likely have put me in Korea.

I felt a bit anxious about my uncertain adventure when I pushed off from a beach on Langara in my kayak, but I was well rested and well stocked with bannock, dried fruit, nuts and adequate fresh water. The swells rolling in off the Pacific were on average two to three metres, but the surface waters were calm, at least until midday. Langara Island was growing distant behind me when the wind came up on the turn of the tide. The eastwardly flooding tide now encountered strong resistance from the southeast wind and the seas built up alarmingly fast. Learmonth Bank, a submerged shoal that would be a substantial-sized island if sea levels dropped a few metres, was directly on my course and the tide was ripping dangerously over it. With the wind stiffening, I had to make a decision as if my life depended upon it—and it did! After a blast of wind and a breaking wave spun my kayak around, I got the message. Years later, Haida elders would tell me that 180-degree kayak spin had nothing to do with weather. “You were sent back to us,” they insisted.

It was well after dark when I found myself wearily trying to work my way through huge breakers rolling over the reefs on the west side of Langara Island. At least I was in the lee of the southeasterly storm, and I could smell the reassuring aroma of land. The flood tide drew me into Parry Passage, where I searched the dark shores in vain for somewhere to land my craft. It was well past midnight when a glowing white beach of crushed clamshells appeared like a ghostly apparition in the dark and I was finally able to pull ashore. I had been cramped in the kayak for eighteen hours, using a bailer for a toilet and drawing my strength from adrenalin more than food. Now my body wanted to collapse, and it did. Too exhausted to pitch my tent, I cuddled up in a dry spot under an old cedar log lying under a grove of young spruce trees. All night long I wrestled with demonic dreams, sea monsters in wild waves and wrens singing for lost souls beneath weathered totem poles.

It was nearly noon before I awoke the next day and wiped the sleep from my eyes, only to wonder if I wasn’t still dreaming. The huge ovoid eyes, flared nostrils and thick lips of a Haida totem pole stared back at me from my place of slumber. Later, I would learn I had inadvertently landed at Yaku, another abandoned Haida village site, and had unknowingly slept under a collapsed totem pole.

I was famished and almost instinctively headed for the tidal zone for food. Thousands of tiny clam geysers spouting from the tidal flats suggested at least one good reason why this village was located here. I was so absorbed in digging for butter clams and littlenecks that I failed to notice a dozen kids sneaking up behind me. Suddenly I was surrounded by the twenty-four muddy gumboots and wet sneakers of a gaggle of Haida teenagers. “What are you doing?” they asked as they looked down at me.

“Digging clams,” I answered matter-of-factly. “What are you guys up to?”

“Watching you,” came the cheeky but very Haida reply.

The Haida youth were all from Old Massett and were working on an archaeological dig at nearby Kiusta Village, another ancient Haida habitation site. One of the boys, Lawrence Jones, in the spirit of Haida hospitality, invited me over to their camp for lunch. I jumped at the invitation; the clams could wait. It was a simple meal of soup and salmon sandwiches, but it seemed like a feast to my famished body. I was so delighted to be safe and in the company of people again that I offered to wash all of the camp dishes. This made me instantly popular with the kids on chore duty and provided a casual opportunity to visit with Nick and Trisha Gessler, the archaeologists overseeing the excavation.

When Nick learned that I had studied anthropology at Michigan State University, he told me they were short staffed and could employ me temporarily while I awaited calmer weather to make the crossing to Alaska. In retrospect, I think he was merely trying to save my life from another foolish attempt at crossing Dixon Entrance. I accepted the generous offer, moved my kayak and camp to Kiusta, and started working on the dig. Kiusta had been the site of the earliest contact with Europeans and the first foreign trade on Haida Gwaii; it offered great promise of significant archaeological finds and insights into that era.

Nearly every day after work hours, Nick and Trisha would encourage me to hike the Kiusta trail that led to a beach on the west coast. I had seen and camped on so many beautiful beaches from Alaska to Honduras over the past eight months that I was in no rush to do so. It was more than a week before I followed their advice.

The kilometre-long trail through pristine rainforest was enchanting, but Lepas Bay itself was more breathtaking than any bay I had ever beheld. A crescent-moon-shaped bay of fine ivory sand framed two lovely offshore islands, one a grassy seabird colony, the other cloaked in old-growth forest. A creek divided the beach and bordered a great rocky outcrop that cut off the northwestern edge of the bay at high tide. For some inexplicable reason I found myself drawn in that more difficult direction.

After climbing the cliffs above the crashing waves, I headed to the far western end of the bay. Dramatic sea stacks adorned in bonsai-like conifers, lush salal, ferns, red columbine, bluebells and yellow cinquefoils rose from the white sands as bold and beautiful as the fabled Hanging Gardens of Babylon. The waters on this end of the bay reflected the jade green of the surrounding forest with sky blue in the shallows gradually deepening to the dark cobalt of the open sea. Eagles nested on the westernmost point, deer grazed peacefully in a meadow of beach grass and a family of otters frolicked over the rocks. All my childhood drawings suddenly came alive in this place. I was home.

A strange compulsion had come over me; I had to do something here. I wasn’t quite sure what it was, but hours later when I returned to Kiusta I found myself as bewildered as the Gesslers with my words: “I don’t think I’m going to work on the archaeological dig anymore, but could I please borrow a hammer, a saw and a handful of nails? I’m going to build a log cabin on Lepas Bay.”

Towering above the beach, this is one of several dramatic sea stacks at Lepas Bay, a place I came to love like no other.

Several weeks later, when the octagonal cabin made of beach logs was already three rounds of logs high, the utter absurdity of what I was doing finally sank in. I already had a cabin in Alaska. Why was I building another one in a country where I couldn’t legally live or work to support myself? I was discussing this dilemma with the Project Kiusta youth around their dinner fire one evening in late August when Clarence, the Tsimshian skipper of a salmon packer named the Ogden, dropped by the camp to say goodbye. “I’m making the last run of the season to Prince Rupert,” he announced. “Anyone need a ride?”

Bringing an end to three months of solitude, a friend unexpectedly arrived on Lepas Bay and shot this photo of me in 1973 erecting the final round of logs on the Navajo hogan–styled roof of my cabin.

Before I was fully aware of the move I was making I had my kayak disassembled and stowed back into the two storage bags, my tent dropped, and all my gear aboard the departing Ogden. The entire Project Kiusta team gave me a rousing send-off from the shore where countless guests had been welcomed and seen off for thousands of years. I sat out on the open deck watching the shores of Haida Gwaii fade away in the dark. I was finally returning to my home and friends in Alaska after a nine-month odyssey. I had come to the Queen Charlotte Islands on a whim and I was leaving on a whim; this was just another stopover on a grander journey. So why was I fighting back tears all the way to Prince Rupert?

A few days later, kayaking west of Ketchikan, Alaska, I really began to think I’d made the wrong move. A storm came up so suddenly that I had to make an emergency landing on a barren rock island with an automated light beacon. I swamped the kayak in a breaking wave near shore, and while I struggled to save my craft and myself, the storm devoured my tent, sleeping bag and most of my food provisions. I had to spend the most miserable night of my life cold, wet and hungry, seeking refuge from the wind behind the only shelter this island had to offer—a steel sign that read, “US Government Property. Trespassers Will Be Prosecuted.” I wished I’d stayed on Haida Gwaii.

When the storm abated nearly thirty hours later, I limped back to Ketchikan in my damaged kayak and set out to re-equip myself with a second-hand tent, sleeping bag, a cooking pot and some grub, all purchased with the small earnings I’d made working at Project Kiusta. In Ketchikan, quite by accident I bumped into a logger I’d met at the Gildersleeve Logging Camp back in December. He had bought a boat and was working as a salmon trawler now, and he offered to drop me off at Cape Muzon. Nearly a month after my aborted attempt to cross Dixon Entrance, I found myself at the beachhead I was striving toward.

The paddle up the west coast of Prince of Wales Island was marred only by the clear-cut scars on the slopes, some of which I’d contributed to in El Capitan Pass. I could see and feel the presence of Haida and Tlingit peoples in this region everywhere, from the intertidal zones where I discovered a beautifully carved stone net weight to the shell middens along shore where the wives of loggers were sometimes seen passing their idle hours by digging (illegally) for glass beads and other artifacts at old village sites. There were living communities too, like Hydaburg, where I enjoyed the local restaurant’s specialty, a Hydaburger, and the Tlingit village of Kate on Kuiu Island, where no one spoke a word to me for two days until it was time for my departure. What I mistook for the rude cold shoulder turned out to be cultural protocol. Strangers had to be observed carefully, often for several days, before being approached in greeting.

One of the most harrowing days of my Southeast Alaska adventure was crossing Frederick Sound, a thirty-kilometre expanse of open water connecting three major inside water passageways where tidal currents ran strong and winds could whip up the waters in minutes. As on my ill-fated attempt at crossing Dixon Entrance, I required a long period of good weather to complete the fifteen-hour crossing of Frederick Sound. This sound also had cross-currents compounding kayak navigation difficulties, so once again I set off at dawn and once again I encountered rough weather midway across. My destination that day was Admiralty Island. Tlingit elders back in Kate had cautioned me again and again, “Whatever you do, don’t camp at Tyee.” Tyee is the name for the southern end of Admiralty Island where three rivers converge to meet the sea. It was late August, prime salmon-spawning season, and huge brown bears were converging here to put on winter fat. Admiralty Island boasts the world’s highest concentrations of Alaska brown bears; they outnumber people living on the island three to one. The Tlingit’s name for the island is Kutznahoo (Fortress of the Bears), and one requires but a single encounter with these eight- to twelve-hundred-pound carnivores to understand the local reverence.

It was nearly dark before I reached the shores of Admiralty; the tide was ebbing south down Chatham Strait and I didn’t have enough strength left in my arms to buck the current. Against my better judgment, and the more than ample warning from others, I found myself landing on the beach of my worst nightmare, Tyee. Half a dozen brown bears were fishing for salmon in the shallow channels spreading out across the broad, muddy tidal flat. I had to haul my kayak and all my gear through ankle-deep mud to get above the tide line, all the while trying to not attract the attention of or provoke the extremely territorial bears. I was utterly exhausted and long past any boost adrenalin could give, having battled threatening seas all day. An old abandoned trapper’s cabin perched on the edge of the forest became my all-consuming goal. If I could make it inside I’d be safe, I reassured myself. A huge bruin caught my movement and started to follow me across the tidal flats at a slow but determined pace. I rushed for the cabin, threw my gear inside and bolted the door. I was famished and exhausted and just about to pull out some trail mix and spread my bedroll when I heard clawing and biting on the wooden door. I must have passed out, because I awoke the next morning beside my backpack fully dressed and wearing muddy gumboots. Fear, exhaustion, or both, had taken their toll.

Paddling the west coast of Admiralty over the next week was exhilarating and more than a little unnerving. The snow-capped mountains of Baranof and Chichagof Islands across Chatham Strait glistened in the sun, but they also created williwaws—strong blasts of wind that rebounded off the high mountainsides and struck the strait with a vengeance. Tidal currents were especially pronounced and it just wasn’t worth the effort to buck tide. Pulling ashore to wait out the tidal change or to make camp for the night usually involved a brown bear encounter. You feel very small indeed when both of your feet fit easily into an Alaska brown bear footprint on the beach where you pull ashore, or when one of these beasts rises up from its grazing in tall shore grass and lets you know with teeth-chomping certainty that it was there first.

Angoon, the only community on Admiralty Island, is an ancient Tlingit site and a delightful living community today. I enjoyed many hours during a rest layover there listening to the elders’ tales over bannock and Labrador tea.

I happened upon another opportunity for income when I arrived by kayak in Hoonah, a small Tlingit village on the north end of Chichagof Island where I was offered a job aboard a salmon packer operating in Icy Strait. My job was simple: to weigh and determine the species of salmon being sold to the packer boat, then to poke ice into the body cavities as I packed the fish into ice bins, belly side up, in the ship’s hold. It was not a bad job; the pay was good and the scenery in Icy Strait was sublime with humpback whales breaching, eagles circling the fleet and sea otters bobbing in the kelp beds. Still, I longed to continue my journey.

It was already mid-September when I finished the packer job and set off again in my kayak for Glacier Bay. Not long after departing Hoonah, I stopped to wait out the tide on a small island at the entrance of Icy Strait that was overgrown in berry bushes. While working my way inland through the thick salal, munching ripe berries by the mouthful, I suddenly came face to face with Kushtaka, the legendary Tlingit Land Otter Man who can transform himself from animal to human and back again. I remembered having seen a photo of him in a book somewhere. The Haida recognize this same animal/spirit being, whom they call Slugu, and it is always an uncertain encounter. I was completely taken aback to suddenly come upon this lifelike face carved in stone and standing at my height in the bushes. It was a mortuary carving on a gravesite island, I came to realize, and quickly departed the isle.

I camped on the south side of Icy Strait the night before the long crossing to guarantee an early start. Shortly after I pushed off from the small beach a heavy fog rolled in, and I spent the entire day trying to navigate the strait without a compass. It was evening before I spotted land again and, as luck would have it, a perfect little landing beach appeared before me through the parting fog. I was thrilled. I had made it safely across the strait—or so I thought. Something was strangely familiar about this beach, and my morning footprints in the sand, crossed over by land otter tracks, confirmed it. I had paddled all day through the dense fog in a huge circle and arrived right back where I’d set off twelve hours earlier. Somewhere there was a lesson in that, or Kushtaka just has a mischievous streak.

When I eventually did cross over and enter Glacier Bay, it proved to be one of the most powerful experiences I’d ever had. I met a young man named George Dyson with a homemade baidarka—an Aleutian-style kayak. He had travelled up from Vancouver to Juneau on a barge and paddled the short distance from there to Glacier Bay. He was looking for a paddling partner to travel to the head of the bay, but I preferred my own craft. We travelled our crafts together up into the bay for several days before he returned to Bartlett Cove and Vancouver. I pressed on to Muir Inlet to view the primal landscape left by one of the world’s fastest-receding glaciers.

To journey from the mouth of Glacier Bay to the base of its thirty-two tidewater glaciers is to journey ten thousand years back in time. One proceeds150 kilometres from climax (old-growth) hemlock rainforest to spruce and scrub willow brush, which gives way to colonizing plants like dryas, lichens, and ultimately barren rock and ice. Muir Inlet in 1973 was opening up at the rate of 1.2 kilometres per year. One could stand on land that had been buried under 1.5 kilometres of ice since the last ice age, and be the first to do so. It was an awe-inspiring experience to work the kayak through the countless icebergs to the very front of the Muir Glacier and watch tons of ice cascading off the face with a tumultuous roar. Then all would become calm again; the waters would glass over and mirror snow-capped mountains and glacier-blue bergs where seals lounged in the sun and dragonflies darted back and forth before resting with outstretched wings on the blue bow of my kayak.

It was already early October before I left Glacier Bay and worked my way up Lynn Canal to Haines, Alaska, and highway connections back to the interior. Thousands of bald eagles were now gathering in the gold cottonwood trees lining the Chilkat River, awaiting the chum salmon return near the ancient village of Klukwan. It seemed much longer than ten months since I’d hitchhiked this road in the other direction. When I finally did reach Talkeetna in the Alaska interior and hiked up the railway tracks to my old trapper’s cabin home, I had nearly a year’s worth of mail piled up on my table, courtesy of my neighbours.

One of the many letters waiting for my return was from a high school girlfriend who had learned that I was kayaking for months along the Canadian coast. She informed me of a Canadian amnesty program designed to legalize US war objectors, draft dodgers and deserters. Anyone who had been in the country more than a few months could come forward and be granted landed immigrant status with no repercussions. I no longer needed to hide my identity, and I could work in Canada.

Haida Gwaii beckoned, but instead I found myself on the road again, hitchhiking to Whitehorse, Yukon Territory. I went straight to the Canada Customs and Immigration office and explained my situation. “Am I eligible under this program?” I asked.

“You certainly are,” a friendly officer replied. “But tell me, how did you get by so long in Canada without being able to work?”

It was too long a story to tell. “I’ll write a book someday,” I replied jokingly.

While waiting for my landed immigrant papers, I was granted a work permit and got a construction job in Whitehorse doing all-night steel work for cement foundations at a new housing development. There was something about wiring steel rods together at thirty to fifty below zero in the dark of a Yukon night that told me this was not my life’s calling. It did, however, earn me the best grubstake I’d had in years, and I was able to return to Haida Gwaii early the following spring to pursue my real dream of returning to Lepas Bay to finish my cabin.

It was April 1974 when I arrived back on Haida Gwaii. After outfitting myself with tools and a few staple food items—flour, rolled oats, rice, milk powder and brown sugar—I set off by kayak for Lepas Bay.

I had written to the Massett Band Council requesting permission to cross Kiusta Indian Reserve to complete building my cabin. I could just as easily have requested a recreation lease on Crown land from the provincial government in Victoria, but I failed to see where the province had any jurisdiction. There had been no treaty, purchase or conquest of Haida lands by any state, so title clearly resided with the Indigenous inhabitants. The response letter from the Massett Band Council was heartwarming: “Thank you for the respect you have shown the people of Haida Village. Permission is granted to cross Kiusta Reserve for the purpose you have stated. We wish you happiness and success in your endeavours on Lepas Bay.”

I didn’t realize at the time that I was embarking on a three-month hermitage; I just had this compulsion to go back. Loneliness is an odd beast, and had I given it much thought it might have deterred me from going. But I can honestly say that it never became a part of my reality in the more than three months I saw no other humans. I found myself talking to the trees, the eagles, the rock spires and the ravens. I spoke not to their physical manifestations but to the spirit of these beings. Spirit was everywhere, and each day of my solitude it became more and more apparent that the boundaries we set to distinguish humans from animals, the animate from the inanimate, and the living from the dead are but feathery figments of our imaginations. If there was a fundamental academic lesson for me in Solitude 101, it was the simple truth that loneliness has nothing to do with being alone. The loneliest experience of my life was standing with ten thousand revellers in Manhattan’s Times Square on New Year’s Eve. My three months alone on the west coast of Haida Gwaii never once brought on feelings of such emptiness.

Lepas Bay likely takes its English name from the Lepas barnacle, a species of gooseneck barnacle that attaches to logs cast afloat for long periods in the open ocean, then washes ashore on storm tides to provide food for eagles, seagulls and scavenging bears. The Haida name for the bay, T’aalan Stl’ang, means “long sandy beach,” but a much older name for the bay, Tidaalang Stl’ang (“medicine man lying down bay”) appears to be in reference to Newcombe Hill (Tidalang Kun), a huge volcanic plug that borders the southern end of the bay. None of these names capture the majesty of the place.

I loved this bay like no other, and I frequently caught myself singing its praises in song. Walking on the beach, slap-happy barefoot in the breaking waves, I bellowed like an opera singer. It was good to be alone. For years my high school music teachers had told me to shut up in choir practice. “You’re tone deaf,” they’d snap, eventually shaming me into silencing myself. Now there was all this bottled-up song inside me that wanted to come out. If it was my destiny not to sing like a lark but croak like a toad, then I was going to do it with all my might; the west coast waves would hear me, and they wouldn’t judge.

Completing my beachcombed log cabin was a joyful undertaking. Each round of logs went up slowly, but each log had a story to tell. I had no chainsaw, only a small Swede saw with a flimsy blade that had to be sharpened after every cut. Sand in the driftwood wore down the metal teeth faster than the teeth of an old cuss chewing too much tobacco. It might take me an hour or more to complete a cut, but in that time I could pause to watch the flight of a falcon or the frantic flutter of a Pacific wren darting among the logs in search of insects, or just drink in the sea’s sweet scents wafting in on the waves.

Simple as it was, there was a universal nature to this house. The octagonal design and domed roof were modelled after the Navajo hogan I’d stayed in at Monument Valley, New Mexico, a year earlier. A slab of red African gumwood, which washed in on the waves, provided a beautiful coffee table and bookshelves that contrasted nicely with the silver-grey planks from a ship’s hold cover that I used for flooring. Japanese inscriptions were carved on the planks I used for my door, and bamboo, which had drifted across the Pacific from Asia on the powerful Japan Current, provided attractive eavestroughs and window lattice that added a touch of charm to my clear plastic windows. Everything seemed to arrive on the beach just as I needed it. The day I finished building a half loft in the cabin for sleeping, I went beachcombing for wood to make a ladder. There, washed in on the tide directly in front of the cabin site, was a teakwood and rope ladder from a Chinese junk. Remarkably, it had just the right number of rungs to reach the loft.

That’s me in 1974, kicking back in gumboots on my Lepas Bay cabin cot that’s covered in a Oaxaca blanket I’d used for a bedroll during my Central American sojourn. Other furnishings included a beachcombed deck chair tossed off a yacht somewhere in the wild Pacific. Richard Krieger photo

I interspersed days I worked on the cabin with days set aside for exploring, food gathering, kayaking, or catching up on laundry and a good book. One thing I noted was how acute and animal-like my senses had become. I was never really afraid, but the slightest movement, sound or smell instantly caught my attention. My balance seemed extraordinary; I don’t recall ever slipping once in all the times I packed heavy logs on my shoulders over slippery wet rocks and unstable piles of driftwood.

When I did finally see another human after nearly a hundred days of solitude, my initial response was to flee into the forest like a startled deer. The upright creature walking toward me on the beach turned out to be a friend from Victoria. Conversation was difficult at first, but when I did start talking I scarcely shut up for days. I also found myself slipping, tripping and failing to notice subtle sounds and movements around me. It was only then that I realized what a numbing effect society has on our basic senses; it dulls the acuteness of our vision, hampers our hearing, and allows us the luxury of losing our balance every now and then. Subconsciously, we rely on others to help us should we blunder; we expect someone to see what we might overlook, hear what we might miss and smell what we might not pay attention to. Solitary bush life, on the other hand, forgives few mistakes; without being paranoid, your animal instincts become acute.

Living on the west coast of Haida Gwaii is a humbling experience; it puts your very existence in perspective. I had been told by Haida elders that listening to the pounding surf too long as waves thunder in from the largest ocean in the world can drive a person mad. A certain level of madness or defiance might be necessary to even live in such a place. There is a small bay just past Hippa Island to the south of my cabin on Lepas Bay that the Haida called Gusgalang Gawga, which translates roughly as “mooning the wind.” Defiance is one thing, but a west coaster must never get too cheeky. Storm waves can toss ten-thousand-pound logs deep into the forest on a high tide, capable of crushing my little Hobbit House like an eggshell, and then there was the ever-present threat of a tsunami.

I was also told by Haida elders that if the surf suddenly went quiet during the night due to a quick drop in the tide, I was to grab a torch and run up a high hill behind my cabin. Ancient Haida legends tell tsunami tales of entire generations of people wiped out by walls of water rising from the deep Pacific.

By July 1, I had plenty of neighbours again. Project Kiusta was back in full swing with the archaeologists and Haida summer students, and the salmon trolling fleet was back for the season. Only ten weeks later all returned to quiet again. I had to make a decision: either paddle back to Masset in early October or be cut off from society for another six to eight months while the autumn and winter gales raged. It was easy for me to see why some people become hermits even if they have no particular issue with society. My period of solitude had been the single most powerful learning experience of my life, but I knew that if I wanted to continue to grow, I needed society again. I closed my cabin for the winter by hanging a piece of carved driftwood on the wall that I inscribed with the words of Lord Byron: “There is a pleasure in the pathless woods, / There is a rapture on the lonely shore, / There is society where none intrudes, / By the deep Sea with music in its roar: / I love not Man the less, but Nature more, / From these our interviews.”

It was mid-October when I paddled my kayak back to Masset and headed down the Island highway to Tlell. Murray Dawson, whose grandfather owned the Green House beside the Tlell River bridge, had offered to share the space with a number of people in need: Trudy Trueheart, Sparkle Plenty, Apple Rosie, Muskeg and others. Somehow a Huckleberry seemed to fit right in, and I was invited to share the space. We were all bedding down on the open-air porch one beautiful autumn evening, enjoying the wonderful orchestration of frogs, when a young Haida man arrived. It turned out to be Gary Edenshaw, otherwise known as Ghindigin, the man playing the congos when I had stayed at Glenn’s house on the Hill. He had been hitchhiking from Masset to Skidegate, and the Tlell River was as far as his ride took him before traffic south ceased for the night. There was still some space on the porch, so we offered him a blanket and invited him to stay the night. It must have been between 2:00 and 3:00 a.m. when I heard a deep voice from the far end of the porch ask matter-of-factly, “Anyone awake?”

The Green House beside the Tlell River is where Ghindigin and I drew the line on the map by lamplight in October 1974 to designate and launch the South Moresby Wilderness Proposal.

“Yeah, I am,” I said softly, not wanting to wake the others.

“Oh yeah, what are you thinking?” came the inquisitive response from Ghindigin, “the Questioning One.”

I explained how I had been dreaming about my kayak trip the year before through the South Moresby wilderness, how I longed to go back there and how it pained me to think that it wouldn’t be the same with the logging starting up on Burnaby Island. Ghindigin was instantly and intently interested. We took our discussion inside, lit an oil lamp, pulled out a map of the southern half of the Haida archipelago and looked at the lines. Tree Farm Licence #24, held by ITT-Rayonier, had three cut blocks remaining to be logged in the South Moresby region: Blocks 3, 4 and 5.

“How far has the logging gone?” Ghindigin asked.

I drew a line south of Talunkwan Island along the border of Blocks 2 and 3, extended it out into the Pacific in the west and Hecate Strait in the east, and brought the lines back together again south of Cape St. James, the southernmost tip of the archipelago. “Proposed South Moresby Wilderness Area,” we printed boldly on the map. Every resident of the Green House who woke that morning was asked to sign a petition calling for South Moresby to be saved. The Islands Protection Committee was born.

It seems astonishing in retrospect that a line so casually drawn would appear on government maps almost from that day forward and galvanize a national debate over land-use issues that would surpass any other in Canadian history. It seems even more extraordinary that this same line on the map survived three government-appointed planning teams, over more than a decade, that were never allowed to consider an option of total protection for the land encompassed by those borders. The most remarkable thing of all is that the line we drew by lamplight beside the Tlell River in the autumn of 1974 is today the exact boundary that distinguishes the Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve and Haida Heritage Site from the rest of the world.

Raven works in mysterious ways.