Say it, no ideas but in things.

—WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS, PATERSON: BOOK I

Artworks draw credit from a praxis that has yet to begin and no one knows whether anything backs their letters of credit.

—THEODOR ADORNO, AESTHETIC THEORY

THE CRITIQUE OF REIFICATION AND THE THEORY/PRAXIS PROBLEM

THE CORE of capitalist reification, as we saw in part 2, is a form of consciousness (and thus of practice) that depoliticizes and obscures the structural basis of capitalism and renders features of capitalist society outside the realm of politics. Moreover, reified consciousness perpetuates the disconnection of theory and praxis by severing critique from its basis in material forms of practice in capitalist society. One of the central motivations of my turn to the critique of reification in the critical theory tradition is to engage its unique approach to the theory-praxis problem.

Both Lukács and Adorno propose distinctive approaches to the theory-praxis problem. Lukács sees the resolution of the issue in the subject position of the proletariat, who occupies the standpoint of totality in its unique status as capitalist society’s subject (a consumer as well as a necessarily “free” wage laborer) and object (insofar as the proletariat’s labor is commodified). While I distance my position from Lukács’s argument that a particular social group can occupy the standpoint of totality, I show nevertheless that the aspiration toward social totality is crucial for a critique of the depoliticizing tendencies of neoliberal capitalism. Adorno’s critique of reification, too, rejects Lukács’s notion of a positive totality, and Adorno turns the critique of reification in a radically different direction, highlighting the centrality of experience to the critique of reification in a way that remains promised but unfulfilled by Lukács’s critique of the antinomies of bourgeois thought.1

Adorno’s response to Lukács emphasized the experiential dimensions of capitalist reification, a materialist gesture that counters Lukács’s idealist totalization of reification. In his Negative Dialectic Adorno demonstrates the way in which reification gives rise to a particular kind of thinking, identity thinking, in which an abstracting and empty use of concepts by subjects repeatedly fails to grasp the world in its materiality, in which the somatic, creaturely and affective dimensions of the world are amputated from the concept.2 The hypostasis of the concept is the philosophical counterpart of the workings of the commodity form: in a world in which the commodity form tends to subsume ever newer areas of social, political, and natural life in its relentless drive for profit, human experience of the world becomes more and more abstracted from its qualitative element and, insofar as that is the case, consciousness surrenders its transformative power.

One of the pitfalls of Adorno’s turn to experience, as we saw in chapter 4, is his separation of the critique of reification from political praxis: for Adorno, dereification can be actualized in philosophy and art, but not in the field of the political. For Adorno, dereification, to the degree that it can happen, occurs in the spheres of philosophy and art precisely because of their disconnection from the immediacy of political praxis. Insofar as art and philosophy are not political, they can preserve the necessary distance from structures of capitalist reification to remain critical. But it is precisely Adorno’s allergy to politics that consolidates the pessimistic turn of critical theory in his wake. I take Adorno’s crucial point regarding the centrality of experience to the critique of reification, but I find Adorno’s refusal of politics to be problematic. I argued that this refusal is ultimately anchored by a commitment, despite himself, to an excessively cognitively centered understanding of dialectical critique in his treatments of reification both in the artistic and philosophical realms.

When I refer to a critique that is excessively cognitively centered, I mean a critical procedure that is not focused on the embodiment of critique or its ambivalent affective and normative entanglements, but instead appeals to rationality, conceptuality, and thought at a discursive level alone. In the context of the neoliberal erosion of liberalism, as I have argued, ambivalence is an inescapable feature of our political situation.3 Brown elaborates this issue in a prescient essay on neoliberal political rationality and the problem of “mourning liberal democracy.”

So the Left is losing something it never loved, or at best was highly ambivalent about. We are also losing a site of criticism and political agitation. … Whatever loose identity we had as a Left took shape in terms of a differentiation from liberalism’s willful obliviousness to social stratification and injury glossed and hence secured by its formal juridical categories of liberty and equality. … What might be the psychic/social/intellectual implications for Leftists of losing this vexed object of attachment? What are the possible trajectories for a melancholic incorporation of that toward which one is, at best, openly ambivalent, at worst, hostile, resentful, rebellious?4

As Brown underscores here, the radical critique of liberal democracy—and of its economic counterpart, capitalism—is characterized by an inescapable dependency, one that manifests as both desire and hostility and resurfaces as a melancholic reincorporation of that which is disavowed. Those who are committed to critique are nevertheless invested in capitalist and liberal fantasies, even as they are vehemently disavowed. Put another way, as Slavoj Žižek humorously offers, we are fetishists in practice, not in theory.

If that’s the case, then critique must wade into the waters of practice by exploring forms of critique that cross the divide between theory and practice and between discursive critique and practical, embodied, affectively and perceptually engaged critique. Critique could explore such ambivalent attachments by taking a form that allows the subject to confront her own multiplicity of attachments and desires, fantasies and commitments with respect to neoliberal society and the bewildering normative and political uncertainty it poses. The critique of capitalist reification could itself become material. Doing so would allow critique to engage affect, embodiment, and the entanglements of desire without sacrificing the self-reflexivity of the subject on these aspects of experience.

Adorno provides a glimpse into a strategy for the kind of critique I am proposing, though in this chapter it will take a different form than Adorno imagined. In Aesthetic Theory Adorno proposes an alternative vision of dereification to his contorted laboring of the concept offered in Negative Dialectic. Adorno argues that the artwork embodies the capacity to provoke dereification through a paradoxical process of autonomy and heteronomy. The artwork can serve as a defetishizing fetish.

In this chapter I propose to use the strategy of the defetishizing fetish to construct the kind of perceptually, somatically, and affectively engaged kind of critique I have been describing. I will do so through an engagement with artworks that build links between subjective experience and structures of capital in a way that allows one to navigate the theory/praxis divide in a distinctive way, one that provokes confrontation of subjects with their own conflicting social, political, and personal commitments and entanglements with capitalist forms of life. I suggest that art is one form of practice that has the capacity to place into question the limits of experience, not at the level of concepts primarily, but at the level of practice, experience, and encounter. Moreover, the artworks I explore here smuggle in critiques of capital through a structural positioning of the subject in impossible, contradictory, or unfamiliar locations of practice, experience, and desire.

Beyond the crucial task of constructing an experiential critique of reification, I also wish to show how the artworks discussed develop an underexplored dimension of the critique of political economy. In chapter 1 I explored the debate between Marxist approaches to the critique of neoliberal capitalism versus radical democratic approaches. I argued that radical democrats have rejected the critique of political economy precisely as a way of motivating politics, rather than suppressing it through the structural focus of a critique of political economy. They have, by contrast, embraced an understanding of politics as autonomous. Marxists, on the other hand, reject the autonomy of the political thesis endorsed by radical democrats due to its inability to grasp the relationship between the political and the dynamics of commodification, production, and circulation that constitute the parameters of the political in the context of neoliberalism. I want to show that the conflict between radical democratic theory and the Marxist critique of political economy, or the dilemma between the economy and the political, is intractable insofar as we cling to a rigid understanding of what constitutes a critique of political economy, one that is bound to excessive cognitivism, allied with an overly rationalistic understanding of how “mediation” is performed, and foundationally severed from experience.

I suggest that artistic representations of capital emerging now in response to the political antinomies of neoliberalism are themselves signs of an alternative critique of political economy, one that is better able to negotiate between political experience and economic form. The key for me is that new ways of representing and inhabiting the economy, what I call econopoesis, are crucial for challenging dominant representations of the economy by mainstream economics, which is both undialectical and in service to financial capital, feeding off the incomprehensibility and unalterability of finance to citizens and political theorists alike. In this chapter I focus on specific artworks that have engaged in critiques of capitalism in ways that press beyond the extant limits of experience and desire in contemporary society, thus putting into question the boundaries between theory and praxis.

All of the works I look at here are focused more or less explicitly on issues of capitalist domination, subjectivity, fetishism, and economic democracy. They operate on two levels: First, they structure an encounter of the subject with her own position within neoliberal capitalism. The artworks I discuss here provoke such encounters in ways that move beyond the purely cognitive and conceptual level of critique to the experiential. Second, many of the artworks engage in aesthetic production about the economy to make it inhabitable in imaginative ways. In this chapter I examine works by Claire Fontaine, Oliver Ressler and Zanny Begg, Jason Lazarus, and Mika Rottenberg to highlight these two dimensions of artistic critiques of capital.

A note on my method: my approach to these artworks is not art historical; it is, if anything, more ethnographic. I am interested in treating the works as forms that structure and position subjectivity within the bounded totality of the work. I approach the works in terms of their experiential impact as well as in terms of their symbolic and formal reference. Furthermore, in my account these works are considered to be works of theory as much as the classic works of critical theory that I have explored throughout this book. My intention is not to instrumentalize the works in treating them as theoretical interventions, though one might fault me for doing so. Rather, by treating the works as experiential theoretical interventions, an aspiration that most of these artists are engaging with self-consciously, the works mediate the excessively cognitive critiques of reification that I have criticized in part 2 and thereby build links between theory and praxis. Reenvisioning the forms that theory itself takes is crucial to my project of constructing a political economy of the senses. Moreover, while engaging with the artworks explored here may presuppose certain knowledges of connoisseurship and access to these forms of cultural production, which might appear to create a class limitation on the accessibility of such forms of critique, the same could be said of theory as such.5 It’s seldom that one seriously criticizes academic theory production (particularly of the left) for its insularity and class-specific accessibility (even when such critiques are obviously justified). Why must we treat artworks differently? If anything, because these artworks are engaging in real-time explorations of subjectivity, they are more accessible theoretical forms than traditional narratocratic forms of political theory.6 They are, in any case, no less accessible. More important, I think it’s crucial to treat these conceptually oriented artworks in the context of my own theoretical work because they model a form of critique that is materially focused not only in content but in form. Artworks such as the ones I examine here therefore begin to perform the work of mediation between theory and praxis that eludes the cognitively centered forms of theory that predominate in the academy. It is my hope and wager that shifting theoretical discussions to a more material frame of reference will ultimately provoke and inspire alternative modalities of theory production.

My concern in this chapter is not with the vicissitudes of aesthetic theory, Adornian or otherwise, but with an engagement of artworks that embody the critique of capitalist reification at a practical level. As I inhabit and explore this series of artworks through the lens of a political economy of the senses, I will make use of Adorno’s notion of a defetishizing fetish that I introduced in chapter 5 as a critical strategy of dereification. To extend the notion of a defetishizing fetish somewhat, here I will hold that a defetishizing fetish is an object or intervention that performs a critical function of dereification precisely in its simultaneous functioning as a fetish and as a troubling, immanent destabilization of the fetish character of that object. I am interested in the ability of the artwork to serve as a kind of theoretical Trojan horse: a gift unsuspectingly accepted by subjects in capitalist society that contains within it a critical weapon. In its role as an “absolute commodity,” critical artworks can exploit this role toward the ends of capitalist critique.7 In Aesthetic Theory Adorno uses the metaphor of a homeopathic counterpoison to describe the critical capacities of the defetishizing fetish. At least as far as immanent critique is concerned, it seems, like cures like. The point I highlight here is that the defetishizing fetish is a crucial strategy for the immanent critique of neoliberal society because it is a form that is suited to the ambivalence of neoliberal subjectivity. Rather than presupposing a stable subject position in relation to capital, a self-identical subject-object of history in Lukács’s terms, the defetishizing fetish is a strategy of critique that is well suited to the ambivalence of neoliberal subjectivity and its conflicting desires and attachments.

The parameters of production and reception of critical artworks, as opposed to critical theory, allow these works to structurally captivate subjects in impossible, incommensurable, and contradictory locations of thought, desire, and imagination. In so doing, they compel experiences of dereification. These experiences are not the end of politics itself, but they follow a logic that radical political practices critical of neoliberal capitalism will adopt as well, as I discuss in the following chapter on the Occupy movement.

EXPROPRIATION: THE LEAP FROM THEORY TO PRAXIS

As self-declared “ready-made” artists, Paris-based duo Claire Fontaine offers its work as a natural candidate for the strategy of the defetishizing fetish. Their work tends to operate by defamiliarizing the familiarity of everyday objects, signs, and significations, revealing the conditions of their production and consumption in surprising ways. Fontaine’s work uses the form of the artwork as a means to propel the artist as well as the viewer between the realms of theory and praxis, reality and fantasy, desire and ethics. I view their work, as well as the other artworks I explore in this chapter, not as exemplary of emancipatory practices per se, but as a way of navigating the gap between theory and praxis in a conceptually sophisticated and experientially relevant way.

As Tom McDonough observes in an essay on Fontaine’s 2009 exhibition Economies, Fontaine’s strategy is one of “expropriation,” as opposed to the traditional artistic strategy of “appropriation.”8 Appropriation would be the artistic turn, beginning in the late seventies, toward the reproduction of existing materials and objects as a strategy for critiquing modernist understandings of authorship and as a way of intervening within hierarchical and homogenizing discourses of mainstream art institutions. Yet, McDonough observes, the strategy of appropriation became integrated into the very institutions that artists had sought to resist, offering itself up as another academic theoretical discourse up for sale. Expropriation both brings found objects, materials, and concepts into the realm of artistic production (an appropriation of sorts) and then also forces them back out in the realm of praxis. In modernity we are already expropriated, in the Marxist sense of the word, dispossessed of the commons, dispossessed of a world of inherent meaningfulness. Expropriation, in Claire Fontaine’s words, “refers to the idea that we live dispossessed of the world and of the meaning of things and that we can borrow signs and objects in order to compose something that makes sense, which brings us back to something we experience.”9

Furthermore, following the model of the defetishizing fetish, expropriation is a way of adopting the expropriative strategy of capital as an artistic strategy in and of itself. Just as capital expropriates the peasants from the commons in eighteenth-century England, and as ongoing cycles of primitive accumulation continue to purge communities of their commons (water, natural resources, social welfare), art in the mode of expropriation will mimic this strategy, but toward critical ends, expropriating material from the realm of the aesthetic into a dangerous and chaotic political situation. In so doing, artistic practices and forms of representation can place radically into question the division between theory and praxis. They do so by means of a chiasmatic movement through appropriation and expropriation, experience and structure, mimicry and critique. By provoking a dynamic movement through such oppositions, Claire Fontaine’s artistic practice embodies the strategy of the defetishizing fetish. I don’t want to argue, for example, that Claire Fontaine illustrates Adorno’s theory: to the contrary, they go far beyond it. They forge a connection between theory and praxis that eludes Adorno and the classic thinkers of reification explored earlier.

Through strategies of expropriation, a number of works by Claire Fontaine bring attention to the incompleteness of the artwork and through this incompletion launch the viewer or the artist into the vicissitudes of a political situation, blurring the distinction between theory and praxis in a critical way. For example, Study for Pill Spills (Prozac Corner) (2010) is a photograph of a pile of what looks like Prozac pills (and in an almost identical work, of Viagra) that are in reality sugar candies. The candies were made in Mexico and then had to be taken over the border to be exhibited in the States. In the end the candies were held up at customs, and so a photograph of the work was exhibited instead. In this case the artwork leaves the protected space of the art world by being taken too seriously for comfort. Though the pills are in reality only candies, and, moreover, only art, the fact that they were held up at customs pokes a hole in the fantasy of free trade, the permeability of borders, and the freedom of expression. The works blur the boundary between art and political-economic reality and, in so doing jolt the viewer out of fetishistic spectatorship. One might be tempted at first glance to view these works at the purely aesthetic level—shiny, glossy, colorful, the pills attract the wayward desires of the viewer. Prozac and Viagra are as plentiful in our society as candy and are perceived to be almost as harmless.

FIGURE 6.1. Claire Fontaine, Study for Pill Spills (Prozac), 2010. Collage, laser print, and pencil. 780 × 1050 cm (307 1/8” × 413 3/8”). Unique. Courtesy of the artist and galerie Neu, Berlin. Photo by Studio Lepkowski. Copyright © Claire Fontaine.

FIGURE 6.2. Claire Fontaine. Study for Pill Spills (Viagra), 2010. Collage, laser print, and pencil. 780 × 1050 cm (307 1/8” × 413 3/8”). Unique. Courtesy of the artist and galerie Neu, Berlin. Photo by Studio Lepkowski. Copyright © Claire Fontaine.

On first glance one might think the work is a critique of the biopolitics of happiness and the medicalization of affect and desire (and so it is). But the critique goes one step further. When we view a photograph of the absent art object, a mishap has taken place. The mishap opens a gap that directs the viewer to the conditions of the work’s production and circulation. The artwork is no longer only art. It becomes a political object in its cycles of migration between sovereign nations in the context of globalized capitalism. And it shakes the foundations of our certainty in the myth of free trade, which, no matter how much Marx we read, we still at some limbic level believe in. The works confront us with the fact that we as a society are addicted to free trade, just as we are addicted to candy, and addicted to Prozac (or its metaphorical sibling, the opiate of “happiness”). Once one begins to unravel the thread of addiction, the affective, economic, libidinal, and political dimensions of our reality are revealed to be indissolubly linked. By bringing the viewer from the level of an immediate and individual experience of the object, which could be defined as the essence of commodity fetishism, in Marx’s terms, to the level of political economy (my addiction to Prozac/Viagra/candy/happiness is somehow linked to the idea of free trade, which is shown in this piece to be a fantasy at a practical level), the work denies the viewer the position of reified, spectatorial subjectivity. It unfolds the viewer’s own dialectic from the experiential level to the political-economic level.

IMPOSSIBLE DESIRES FOR THE POLITICAL: BURNT/UNBURNT

I take Study for Pill Spills as an objectified treatment of the theory/praxis problem. By contrast, another work by Fontaine, burnt/unburnt (2010), brings us into the realm of a defetishizing fetish, moving the viewer from a spectatorial and reified position to a more engaged and dialectical relationship with the work and the political-economic situation it references and creates. Burnt/unburnt was the first work by Fontaine that I myself viewed in person. Because the work plays with the relationship between individual experience and abstract social structures, I think it’s useful to walk through my own thought process as I viewed the work, as it helps to illuminate the dialectic of experience that I want to highlight in the work. Burnt/unburnt is a cluster of over one hundred thousand matchsticks embedded (in this case) in a classroom wall in the shape of a map of the United States, complete with Alaska and Hawaii. Fontaine has made several versions of the work, each fashioned into the map of the country of exhibition.

FIGURE 6.3. Claire Fontaine. America (burnt/unburnt), 2011. Burnt/unburnt matchsticks, dimensions variable. Edition of 1 plus I AP (installation image).

FIGURE 6.4. Claire Fontaine. America (burnt/unburnt), 2011. Burnt/unburnt matchsticks, dimensions variable. Edition of 1 plus I AP (matches detail).

Upon the first glance at the work, I admit I was underwhelmed, although at a visual level the pixelation of the matchsticks is ephemerally mesmerizing, like a 3-D mechanized Seurat. There is a false topography suggested by the concentration of matchsticks—the size and quantity is striking, but basically I thought it looked a bit like a neurotic craft project displayed on the wall of a classroom.

Except …

Then I began to think about what the artwork could be rather than what it is. This work, I thought, would be so much better if I just held a flame to it and watched it blaze. If … if … if only …

But I would never do it. Never.

Why not?

Yes, why not? Well, to begin with, because the artwork is private property in its most sacred form. It’s arguably worse to burn an artwork than to burn an SUV. Even in these postmodern times the artwork can never quite shake its phantasmatic aura. And I would never burn a work of art—after all, it’s not mine. Never mind that the work probably totals to about two hundred dollars worth of matchsticks. Never mind that the artists might be a bit excited if I committed the unthinkable act. I would surely get arrested for burning it, especially since the fire would damage dozens of other works shown in the space.

There’s nothing political in the first instance about the desire to set this work in flames. Yet, because the work is a map of America, that act couldn’t fail to be political, a desecration of a symbol of the United States. At one and the same time one would violate laws against the destruction of private property, “laws” against the sacredness of art, and laws against the destruction of the symbol of the United States. It’s in the equivalence manufactured between these three levels that the interest of this work lies. Private property = artwork = America.

Provocatively, the work forces the viewer to somatically and mentally inhabit the future conditional tense in the fleeting twitches of her own desire and to suffer the disappointment and failure at the heart of the work. The “if only” never becomes actualized. No one burns the work. No one acts on ephemeral desire. And so every viewing of the work places one in the uncomfortable position of bearing witness to political failure and interpellates the viewer into spectatorial consciousness.

“I wouldn’t dare.”

I should note that Claire Fontaine herself does burn the work in public. Of course, it’s their work, so I don’t see this demonstration as a violation of the logic I previously outlined, though I do admire this gesture as a provocation to action and as a refusal of the reified subjectivity that the unburnt work interpellates.

FIGURE 6.5. Claire Fontaine, America (burnt/unburnt), 2011. Burnt/unburnt matchsticks, dimensions variable. Edition of 1 plus I AP (burnt image). Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York. Photo by James Thornhill. Copyright © Claire Fontaine.

Furthermore, the work plays with the spectral and elusive existence of the economic within the awareness of neoliberal subjects. The work itself is a painstaking assemblage of thousands of matchsticks put together by the two artists that make up Claire Fontaine, who jokingly refer to themselves as Claire Fontaine’s artist assistants. In this imaginative construct they are employed in a particular kind of wage labor, which is painstaking and repetitive, bearing little resemblance to the traditional conception of artistic labor as creative and self-realizing. They are closer to Lukács’s spectatorial subjects working under conditions of reified labor than to the creative classes of cognitive capitalism. Appropriately, in one’s perception of the artwork the economic is largely obscured and fleetingly revealed only through a baroque symbolism: the map of the United States represents the economic through a political refraction. But labor itself remains invisible.

With burnt/unburnt, Claire Fontaine sets up a bald illustration of how capital sabotages political desire in utero. The work foregrounds the micrological and experiential dimensions of the murder of spontaneous desire and draws attention to the spectral presence of the economic in quotidian perception.

ALTERNATIVE ECONOMIES

Another of Fontaine’s strategies is to reveal hidden layers of what we take to be an economy through an interface that is both rudely experiential and subtly conceptual. The capitalist economy, on their understanding, is not merely a system of commodity exchange but also a system of desire and a structure of appearance. There are many economies in what we take to be “the economy.” One of Fontaine’s signature strategies is to explore hidden economies that call into question the monolithic character of the capitalist economy and that serve as its conditions of possibility.

Change (2006) displays a pile of quarters that have been subtly altered with retractable metal boxcutter knives hinged to the edge of each one. The knives are easily hidden and provoke fear at the first glance. No doubt in the United States, at least, the first association with boxcutter knives is the terrorist attacks of 9/11, and one feels a rush of anxiety at the idea of how easy it would be to smuggle these quarters through airport security. Perhaps the artists even managed to get the quarters through security for the show. This first association with terror links the idea of terror with capital (money). Citizens of a capitalist society are in constant fear of terror from the outside, yet we ignore the terror within that is functional to the reproduction of the capitalist social form. Money is something we need and desire, and yet in this work it becomes turned against us. The inversion of the innocent quarter into a deadly weapon provokes the question: do we suffer more from terror committed by foreign, Islamic radicals or self-terrorization by the economic system we live under? Provocatively, Claire Fontaine links these two levels.

FIGURE 6.6. Claire Fontaine, Change, 2006. Twelve twenty-five cent coins, steel box-cutter blades, solder and rivets, approx. 90 × 40 × 40cm. Edition of 1 plus I AP. Courtesy of the artist and galerie Neu, Berlin. Photo by Studio Lepkowski. Copyright © Claire Fontaine.

At another level, the work explores the hidden violence that suffuses the capitalist economy: an economy of violence underlies the economy of money. We tend to see quarters as harmless things, beautiful and shiny, coins we would put in a child’s piggy bank or happily fritter away at a slot machine. Yet the knives emerging from the quarters look almost as if they have always been there—lying beneath our perceptions of money there is a dagger. The title plays with the relationship between politics, economy, and violence: “change” is a reference to coins on the one hand, to “small change”—something ephemeral and small. On the other hand, change could also refer to the idea of revolution and the relationship between violence and revolt. If we want change, so the work suggests, we will have to learn how to turn small change into a weapon for change. We could see this statement both literally (turning coins into knives) or metaphorically (turning the economic system into an agent of change).

Redemption (2011) is an installation of garbage bags filled with empty soda and beer cans hanging from threads attached to the ceiling of the gallery. The work explores the relationship between art, economy, and social labor. It’s characteristically humorous that Claire Fontaine would hang bags of what is basically garbage all over an upscale art gallery in Chelsea. The garbage bags look a bit like punching bags, suggesting a kind of impotent release valve for economic frustration. The hundreds of beer cans also bring to mind a sense of the day after the party—the party is over; now we have to clean up. This is perhaps a gesture to the financial crisis, a result in part of unbridled “partying” and speculation by financial elites, as well as a reference to Occupy Wall Street, who in effect is cleaning up the mess.

FIGURE 6.7. Claire Fontaine. Untitled (Redemptions), 2011. Recycled cans, 55-gallon clear bag, dimensions variable. Unique (installation image).

Beyond the metaphorics of economic crisis, at a literal level the work is the result of a real economic transaction. Claire Fontaine actually bought the cans from people who were rummaging around the trash to collect them hoping to exchange them for money. And herein lies the redemption: just like the act of redeeming aluminum from trash and creating wealth out of it, the artist is creating wealth out of trash—and there might be something redeeming about this. But if there is something redeeming about it for the “artist,” one has to ask, how is this act different from the act of the homeless garbage collector? In the center of the same room a hand mirror hangs from the ceiling, slowly revolving like a disco ball. The mirror evokes the theme of self-reflexivity, an image of oneself reflecting as one observes. Do we all redeem something in the act of reflection? And is it the very act of reflection or mediation that transforms something from garbage collection into art (or theory)? This idea suggests something of a poke in the ribs to artistic production—that the exhibition space is no more than a hall of mirrors. In the hands of the hobo it’s trash, but through a few magician’s tricks it turns into something of value. But then the redemption, so the mirror suggests, is not the redemption of garbage into art performed by the artist but the redemption that the realization of symmetry between artist and garbage collector performs in relation to the concept of social labor.10

THE BULL LAID BEAR: CRITIQUE VIA THE TROJAN HORSE

The Bull Laid Bear (2012), a video work by Oliver Ressler and Zanny Begg that is part documentary, part animated cartoon farce, pursues the difficult task of narrating the events of the 2008 financial crisis in terms that are comprehensible to people without boring them to death.11 Boredom is a serious issue, the video suggests, when the events in question are not primarily agent centered but concern a structural crisis of capital, when existing norms and institutions of global and national justice are inadequate for comprehending the wrongs committed and when the details of finance are themselves so opaque and so abstract that it takes a superhuman effort for the average educated individual simply to understand at the level of facts what in the world happened, let alone stay awake while someone explains the situation.

The work refuses the viewer the option of boredom from the start, beginning nostalgically in the middle of what looks like a 1920s-style piano bar with a sequins-clad singer crooning a song by Billy Holiday, “Them that’s got shall have, them that’s not shall lose / Better have deep pockets, if you like those shoes / Mama may have / Papa may have / but I wanna man whose got his own / whose got his own” she sings, a bit too loudly for comfort with a brassy and bracingly nasal timbre. It’s not boring, surely, but it’s not comfortable either. The video turns to a conversation with white-collar criminologist William K. Black, who sits at a bar with an animated pitcher of beer. “Have you heard the one about the Irish?” flashes across the screen in text, suggesting that Black is about to tell us a (perhaps racist?) joke. And indeed, he is—one about the Irish bank bailout in 2008, the bailout widely held to be the one that precipitated all subsequent bailouts: “The Irish one is quite amazing, because it is the dumbest governmental reaction to a banking crisis in the history of the world,” Black quips.

FIGURE 6.8. Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler, The Bull Laid Bear. Film, 24 min., 2012. Film still.

He goes on to give the details of the bailout, noting that the Irish people bailed out the banks by repaying creditors that had made the very riskiest loans though there was absolutely no obligation for them to do so, thereby turning the banking crisis into a budgetary crisis at the national level for Ireland. The winners in this case, Black tells us, were the German banks, Deutsche Bank, and many of the regional German banks, which had made the risky loans, belying their undeserved spotless reputation. “German banks within Germany have the reputation of being very staid and careful, alles muss in Ordnung sein,” says Black. “But outside Germany it’s like ‘Girls Gone Wild.’”

The video cuts to a debauched shot of the bankers, signified by cartoon bears wearing bank logos on gold chains around their necks, the techno beats of a pop song, “Girls Gone Wild,” playing in the background. One snorts cocaine off the table, another is involved in a liaison with what appears to be a sex worker in the back of the room, a third one bears his nipples to the camera. But the acerbic humor quickly turns serious. Black delves into the nitty gritty details of the Irish case as he talks with an animated tattooed punk sitting across from him at the bar. As Black goes deeper into the story, the punk looks at us ever so often and nods in a gesture of compassion and mutual understanding.

FIGURE 6.9. Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler, The Bull Laid Bear. Film, 24 min., 2012. Film still.

FIGURE 6.10. Zanny Begg and Oliver Ressler, The Bull Laid Bear. Film, 24 min., 2012. Film still.

For the viewer it is the emotional attachment to the young cartoon man that allows one to keep listening to Black. Black, who occupies the position of the critic, almost seems to be taking pleasure in the absurdity of the story about the bailout that he is telling, and he is clearly pleased at his own ability to understand all the intricate economic details, which he goes on about at length. The viewer cannot really identify with Black, not having the expertise he does, and thus the viewer can’t occupy the position of the critic. Instead, the viewer is positioned to identify with the young cartoon everyman. But then, as the man walks out of the bar, a gigantic animated razor neatly lops off his head, with the text accompaniment “The Irish Haircut” flashing across the screen. The character with which the viewer could most identify has been sacrificed, albeit bloodlessly.

The video oscillates between commentaries like the one just described, where expert critics break down aspects of the financial crisis in layman’s terms as if they were talking to us in a bar, and animated courtroom scenes where the experts (represented by real human commentators) actually appear to be giving testimony in a trial against the megabanks, represented always by cartoon bears wearing the insignia of Chase, Bank of America, Deutsche Bank, and Wells Fargo.

The most obvious read of the video is that it is a pedagogical piece, breaking down the events of the 2008 crisis and bailout for the average citizen and dressing it up in visually appealing and humorous form to push back against the inherent complexity of the material. At the level of content, the video performs the important work of providing a dramatic structure to economic events that defy narrativization. The very inability to establish winners and losers and to contextualize the events of the financial crisis within the frame of a story, even if that story is a tragedy cum farce, is at the core of the deficit of critique in the light of the events of 2008, many of which seem outrageous as depicted in the hands of Ressler and Begg. This is a story about bringing the wrongdoers to justice. It is, at its heart, a liberal critique of the economic crisis. The commentators make use of liberal norms in their albeit harsh critiques of the activities of banks and governments in the wake of 2008. For example, Black often makes points about how principles of neoclassical economics were violated by the covert activities of the biggest banks, thus pointing, ultimately, to their sufficiency as a norm. His critiques of the idea that the banks were “too big to fail” is that in fact the system would be much more efficient if the banks were broken up and made into smaller, more manageable institutions. This is not a radical critique of capitalism, but very much a moderate liberal critique of it. In the content of the commentary the experts do not say much that would put off the average, cable news–viewing public. In fact, it is precisely this public that is addressed so as to provoke outrage on their part of the injustices that have been done. At the level of content the video presents a story that is more about corruption than a systemic crisis of capitalism.

However, the deployment of strategies of distantiation at the level of form, in the sense of Bertolt Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt (estrangement effect), suggest that something deeper is being evoked beyond the liberal pedagogy.12 From the beginning, the presence of the loud and awful voice of “Singing Sadie” provokes a jarring effect that is meant to put the viewers on edge. Don’t get too comfortable, her voice seems to say. The strategy of setting the discussion in a space of indistinction between a bar and a courtroom point to two comfortable political fantasies of the present that Ressler and Begg would rather unsettle: the fantasy of a functioning liberal public sphere, of the Habermasian variety circa The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere,13 and the longing for a delineated space of justice where capitalism could be “put on trial,” as it were. Yet in the video both these fantasies seem to function as fetishes. The bar appears oddly quaint in an age where the only thing akin to a liberal public sphere happens in the impersonal and littered nonspace of the Internet, where apolitical hyperexpression results in a simulacrum of politics. As for the courtroom, it is never clear in the film who is bringing the charges against the banks. In the back of the courtroom the only spectators are the headless young men sacrificed by capital. And at the moment of truth, when the judge (who is a cartoon bear, like the bankers, rather than a human) is about to declare a verdict, he instead raises his gavel to his mouth and takes a hit off of it as if it were a pipe, holding the smoke in his chest for a long, pregnant moment before he exhales. “Are you stoned?” the image mockingly asks us. Both these fantasies are opiates, so the work suggests, however much we might long for them.

Most interestingly for my purposes, the work smuggles in the radical critique of capitalism through the back door, so to speak, at the end. After twenty minutes of unobjectionable, though intelligent and often hilarious liberal critique of financial corruption, a quote from Brecht’s Threepenny Opera appears on the screen: “What is robbing a bank compared to founding one?” At a political level this quote is curiously out of joint with the rest of the commentary, with its Marxist implications that the entire system of capitalism is pervaded with injustice: the financial crisis is in fact no exception to business as usual. In a sense, the real message is here. Unsuspectingly, the viewer has been taken through a fairly tame narrative about financial crisis that he can largely subscribe to, and then Ressler and Begg take a wager on the distracted viewer: if you agree with all the prior critiques of the crisis, you’ll have to agree that the entire system is flawed. And, if not, you will at least be shocked by association out of your complacent cable news outrage. In a distinctive way, The Bull Laid Bear, like Claire Fontaine’s work, functions as a defetishizing fetish that works cunningly to transform the position of the reified subject’s relationship to the economic at an experiential level.

CAVEAT EMPTOR: THE FETISH OF CONSUMPTION

Squeeze (2010), a video work by Mika Rottenberg, explores the position of racialized feminine bodies in the cycle of global capitalist production and circulation.14 The film depicts an impossible, fantastical machine that links the labor of female bodies exploited across time and space. A group of Indian women relentlessly scrape bark off rubber trees and collect its milky sap drop by drop in tin pales. Mexican American women, in what turns out to be Arizona, harvest light green heads of iceberg lettuce, gruesomely hacking the ends off of them in motion before they hurl the heads onto a conveyer belt. A very large African American woman sits on a giant, wooden lazy Susan whose turnings, which are driven purely by her immaterial, spiritual labor, seem to power the entire time-space machine. With every turn, the machine produces a disgusting cube made of the lettuce, the rubber (which grotesquely resembles the jiggliness of human cellulite), and pink blush, the latter of which turns out to be produced through the sweat of a white woman who is being pressed almost to death by the machine’s revolutions. The film cycles through these settings, which are improbably connected by the machine. At one point the Indian women lay their heads down on the ground, appearing to sleep, but in fact their hands are stuck down a surreal Alice in Wonderlandesque hole that allows them to receive manicures from a team of Asian beauty workers in New York City.

FIGURE 6.11. Mika Rottenberg, Squeeze, 2010. Single channel video installation and digital C-print (film still). Duration: 20 min. Dimensions variable. Edition of 6 + 3 AP. Copyright © Mika Rottenberg. Courtesy Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery, New York.

Both humorous and thought-provoking in its focus on crucial issues about femininity, race, exploitation, and labor, I initially took this video as an example of an artwork that is critical in content but not in form. In its representation of the labor of feminine bodies, the video does not play with the reflexivity of the viewer or the positionality of the viewer in relation to content. We watch the bodies of third world and exploited first world women occupy dehumanizing positions. The film’s vertiginous shifts in setting underscore the irrationality and complexity of the processes of capitalist exploitation in the context of globalization. Ultimately, the machine’s production of the lettuce-blush-rubber cube makes the apt Marxian point that use value is increasingly being subsumed by exchange value in late capitalism: an excessive amount of labor produces no more than a big, disgusting cube of useless detritus, a metaphor for capitalism’s will to nothingness.

Yet watching the exploitation of third world women’s bodies is (sadly to say) nothing terribly new to the average viewer of Rottenberg’s work. Do we stand in a different relationship to their labor after viewing the work? Does the work place one in a structurally different position vis-à-vis our own experience and its relationship to forms of capital? Are we bound by the strictures of the work itself to occupy a structurally new position in relation to the exploitation of women’s labor in contemporary capitalist production? In my intitial read of Rottenberg’s video, I felt that the answer to these questions was no. The work is imaginative, but its imaginative construct exercises no structural compulsion upon the viewer.

Yet I revised my read of the work after considering techniques that Rottenberg used to extend the work beyond the video format—I realized that perhaps this work appeared uncritical because it functioned so effectively as a fetish. External to the video itself, Rottenberg uses critical strategies to explore issues of fetishism and commodification of art as well as broader issues of consumption. For example, Rottenberg had the rubber-lettuce-blush cube that appears in the video materially manufactured. In the exhibition of the video, she displayed a photo of her smiling gallerist, Mary Boone, holding the cube as if it were an ad from the 1950s for Wonder Bread or Prell shampoo, thereby placing the relationship between art and commodification front and center.

FIGURE 6.12. Mika Rottenberg, Mary Boone with Cube, 2010. Digital C-print (one component of Squeeze installation). 64 × 36 in. 162.6 × 91.4 cm.

But instead of selling the cube, Rottenberg shipped it to a safe deposit box in the Cayman Islands, in which people could then buy shares. Like shares of any stock, the shares could either go up or down in value. The materially produced cube is sort of like an action figure manufactured to go along with the video. This strategy is perhaps almost a bit too successful as a defetishizing strategy—it is hard to actually distinguish it from the “real thing,” from an action figure manufactured to go along with a blockbuster film. When Rottenberg produces and sells her cube (or photo/video reproductions of it), it is likely to boost the artistic capital of her piece just as it would for a Hollywood film. One question that her work raises is how artistic practices maintain autonomy from the consumption of artistic critique. One way is to make the work literally unconsumable, and in a way this is what Rottenberg has attempted with the manufactured cube. Insofar as it’s locked up in the Cayman Islands, it’s unconsumable. People can buy shares in it, but they would be doing so as a conscious consumption of the critical content of the piece itself rather than from any fetishistic or sensual pleasure they could take in owning the material art object itself. I think that it is in these aspects of the work, combined with the visual critique of the video, that a defetishizing strategy exists.

PHASE 1: THE FETISH OF POLITICAL AFFECT

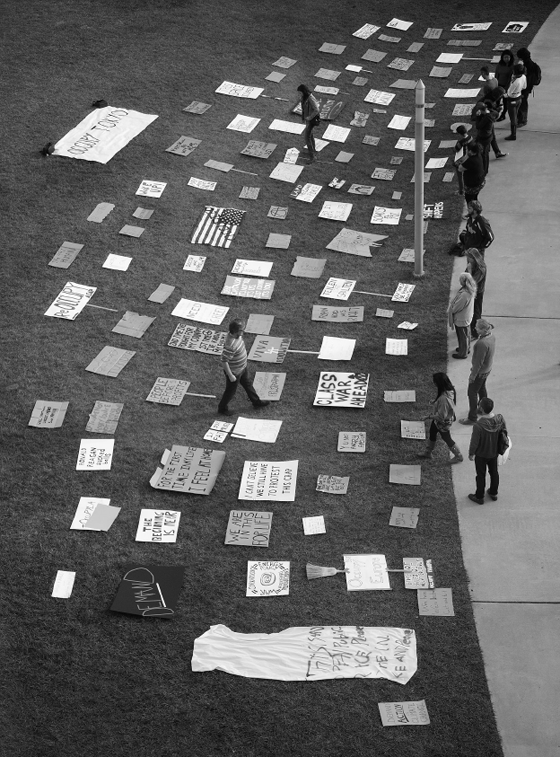

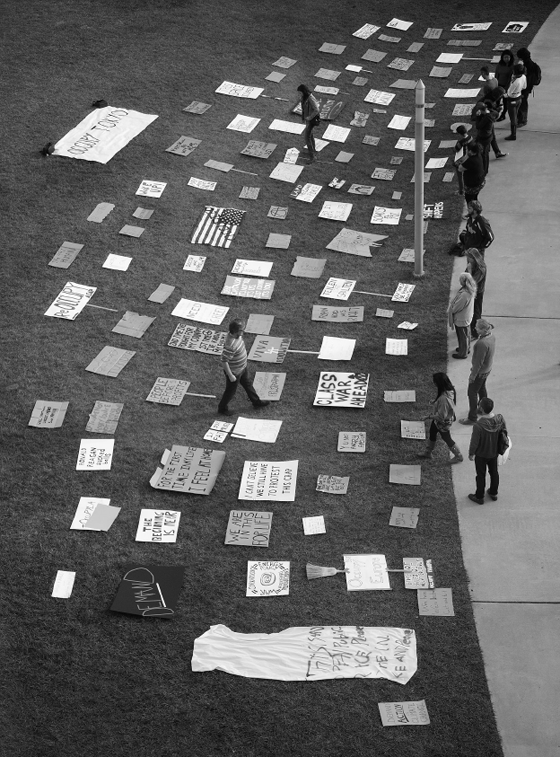

Jason Lazarus’s Phase 1/Live Archive self-consciously situated itself in the liminal space between art and politics from its inception, problematizing the distinction between these two realms. Within the bounded totality of the work, this piece complicates key dimensions of neoliberal subjectivity by playing with the relationship between political practice, history making, artistic consumption/spectatorship, and political affect. The project began in October 2011 when the Chicago artist became fascinated by the handmade protest signs that were circulating around the Occupy Wall Street movement, many of which echoed recent images from Tahrir Square and the Arab Spring movements. Lazarus began to digitally collect and then to recreate as many signs as he could from the Occupy movement. First working in Florida, where he was at the time serving a residency, Lazarus worked with undergraduate students to replicate images of the signs found on the Internet by hand and display them in public. He then brought the project back to Chicago in early 2012 just as many of the Occupy sites were being forcibly dismantled.

FIGURE 6.13. Jason Lazarus, Phase 1/Live Archive at the MCA Chicago (2013; gallery shot).

The signs displayed in Phase 1/Live Archive are created during sign-making workshops where participants translate the image of a sign from Lazarus’s internet archive of Occupy signs into a literal three-dimensional copy. In both exhibitions of the piece Lazarus holds the workshops in the museum itself, thus creating a situation where one is simultaneously enlisted as a “producer” and “consumer” of the artwork. In the process of recreating the signs, participants are asked to use the same or similar materials to duplicate the sign’s text as well as any creases, bends, tears, or other distinguishing marks. The signs are then displayed in the museum, where visitors can pick up a sign that interests them and carry it around while they view the work, evoking Marx’s well-known thesis on history, that men make their own history but not under conditions of their own choosing.15 In this case the first time as tragedy, the second as art.

FIGURE 6.14. Jason Lazarus, Phase 1 Live Archive at the MCA Chicago (2013; outdoor shot).

The sign-making element introduces a significant tension into the artwork, as subjects are at one and the same time standing in three potentially divergent positions in relation to the work: as artist, as historian (who documents work from and for an archive), and as protester (by holding a sign to whose message you ascribe).16 Rather than separating producers and consumers of art and of history, one occupies the position of both. The exercise of recreating a sign from an already existing archive enacts political protest as a learning process, one that becomes public. By walking around the museum with a protest sign, or by participating in a sign-making workshop, participants open themselves up to an iterative process of subject formation, but one that is ridden with ambivalence and tension. Maybe you don’t particularly like any of the messages depicted in the Occupy signs; maybe you carry around or reproduce a particular sign ironically.

A few formal elements regarding the archive itself are important to note. The archive consists of digital photos of Occupy signs in JPEG format. JPEG is a “lossy” medium of digital compression, which means that in saving an image as a JPEG file, information and image quality are lost in each iteration (as opposed to a “lossless” format like TIFF). When participants recreate the image of a sign, they are in a sense sculpturalizing a digital image and revoking the “loss” of material that happens in the dissemination of the JPEG. The act of sculpturalizing images serves as an embodiment of a typically disembodied process that references the way in which online sharing and tweeting create a loss or dispersal of the impact of a political message or event. Participants are (re)materializing a digital image that has already “lost” its relationship to action and, in doing so, producing a new relationship between images and action. Whereas Facebook algorithims typically create a situation in which like encounters like, with little alterity, in the context of Phase 1, carrying around a sign that you “like” gives weight, objectivity, and publicity to those preferences, all of which seem important to the creation of political subjects and that, moreover, seem to be increasingly lost in the context of communicative capitalism. Phase 1 works to materialize the increasingly immaterial world of preferences, opinions, and commodities we increasingly inhabit in the contemporary cyberecology.17

Parallel to the production and display of Occupy signs, the exhibition features an advanced student pianist playing Chopin’s Nocturne in F Minor on the other side of the gallery space (Untitled). The pianist has not learned the piece prior to the exhibition, but rather spends his time in the museum practicing the piece. The pianist fills the exhibition space not with a polished performance of the music but with mistakes, repetitions, and ultimately with his own interpretive take on the piece that perhaps goes beyond the bounds of what most classical musicians typically take to be artistic license. The staging of the piece makes a learning process public—it unfolds the contained event of performance into a series of iterations, errors, improvisations, and resonances, a musical reflection of the way the Occupy movement embodied a learning process for a new approach to practicing antineoliberal politics.

FIGURE 6.15. Jason Lazarus, Untitled, 2013. Kawai grand piano, piano bench, sheet music, and pianist, MCA Chicago.

Lazarus’s selection of the nocturne is a clear artistic choice. Nocturne in F Minor is an emotionally evocative piece. It would be difficult to listen to any part of it without being affected by its somber, heavy quality. At times mournful, at times agitated, at times sentimental, the music contrasts provocatively with the staging of political action taking place on the other side of the gallery and seems deliberately calculated to produce an emotional and somatic effect on the part of the viewer. The presence of the music shifts the time-space continuum of public viewership. There is something potentially manipulative about this gesture, which perhaps seeks to produce affect and empathy where there is none. It is almost as if the presence of the music induces me to feel mournful for the failure of the Occupy movement or anger for the injustices perpetrated by casino capitalism or longing for a society that values community and human togetherness. The Chopin seems bound to induce a form of “cruel optimism,” to use Berlant’s term, precisely through its injunction to make one feel something at all.18 The signs and the pianist stand out of sight of one another, but one can hear the strains of the piano throughout the museum while viewing the signs.

But perhaps it is through the affective register of the music that the defetishizing strategy enters. The hyperemotionality of the Chopin (as Adorno might argue) is itself a fetish.19 This suspicion would seem to be confirmed by Eva Ilouz’s argument that contemporary capitalism has given rise not to a bureaucratized and nonemotional world, but rather, on the contrary, to a hyperemotional culture in which economic relations have become emotionalized and personal relationships have become rationalized.20 The Chopin compels the viewer to have an emotion—only a completely numb individual doesn’t tear up a tiny bit when listening to Chopin. But emotions are nothing rare for “homo sentimentalis.”21 Yet one could contrast this sensory experience with the more quotidian soundtrack of popular culture—mid-tempo beats, autotuned voices, a hollow shell of digital sound—that seems deliberately designed to produce a bounded affective response. By pairing the live Chopin with the viewing of the Occupy protest signs, the viewer is set up to have a political emotion, for even if the emotion is parallel to the political narrative it is nevertheless synchronized with it. That emotion could be sentimentality, stormy rage, or a whole range of other affective responses, but the point is that whatever emotion arises it becomes the occasion for questioning one’s identification or lack thereof with the Occupy movement and with the issues it raises. Yet, simultaneously, the music is being constantly interrupted—one is listening to someone practice the piece, not perform it. This interruption could be frustrating, and it could also be a relief. But it complicates the relationship between affect and politics in a reflective way. It treats political emotion as both a fetish and as salient for an empathetic response to neoliberal domination.

Each piece, Phase 1 and Untitled, frames our perception of the other. They are dynamically engaged in a reciprocal commentary on the processes of political subject formation and history making. The fits and starts of the piano can be felt, perhaps with frustration, as the wobbling genesis of a political movement finding its message by writing the score as it plays. The interplay between the register of political action, depicted by the signs, and the register of political affect, deployed by the music, also speaks chiasmatically to the relationship between collective and individual processes in politics and their emotional resonances. On the one hand, the music might signify and magnify the emotional dissatisfaction the individual inevitably feels by participating in a collective political movement, with its setbacks as well as victories, with its disorganized general assemblies and the compromises of consensus, while the sign making embodies the satisfactions of political collectivity and of acting in common, of being submerged in the collective, if only for a moment. On the other hand, the music might alternatively signify the turbulence of collective affect in the wake of 2008, since the music inhabits the gallery space at an atmospheric level, while the sign making could be seen as a process of developing an individual attachment to a political message. One experiences both by inhabiting the artwork, and ultimately the point seems to be to experience and embody the affective tension of politics in contemporary neoliberalism. That tension may result from the conflict between one’s own political apathy and the encounter with the artifacts of antineoliberal occupations or it may result from the conflict between one’s identification with Occupy and the spectatorship that the movement has been reduced to in the exhibition.

In the final chapter I continue this exploration of ambivalence, affect, and desire in the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011 by looking at Occupy’s own deployment of the defetishizing fetish strategy in its modes of political organizing. I focus above all on the way in which Occupy has explored these issues as connected to, rather than separate from, a critique of political economy.