ONE

A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A SOCIALIST CITIZEN

I’M WRITING THIS book in 2018, so if you’re picking up a dusty copy some day in the future, you should know that Jon Bon Jovi is the most popular and critically acclaimed musician of this era. With that in mind, let’s try a thought experiment.1

Say you’re a big Bon Jovi fan (and really, why wouldn’t you be?). You’re looking for a job, and you write Jon Bon Jovi a letter with your resume attached, and he’s kind enough to give you a reference to work for his family’s pasta sauce company. Now, as contemporary readers will no doubt know, Bongiovi Brand pasta sauce is widely regarded as the finest pasta sauce. You take your position there bottling such Italian American favorites as “Classic Curry” sauce with great pride.

You’re paid $15 an hour and work from nine to five every day. It’s not great, but you have bills piling up and weird hobbies to pay for. It’s certainly better than being unemployed and stealing Wi-Fi from your neighbor Fred, a twice-divorced pediatrician who cried at the end of The Blind Side.

Despite the unrivaled quality of their product, Bongiovi is still a small firm. You’re quickly trained in the most efficient way to bottle and seal pasta sauce. It’s mind-numbing stuff, but otherwise things are okay. You take a liking to your coworkers and make friends.

Over the months, you become better and better at your job. It might sound silly, but you take pride in the work. You believe in “Classic Curry” and its capacity to bring joy and satisfaction to people across the world. You also get along great with your bosses—it’s a pasta sauce factory, not some Dickensian sweatshop. When you look sad, your foreman asks you what’s wrong and tries to cheer you up. When you make a mistake, you’re not fired, but given some friendly feedback. Mr. Bongiovi even occasionally treats his employees to a Trenton Thunder minor league baseball game after work.

On your one-year anniversary at the company, you get to counting. You used to bottle 100 pasta sauces a day—now you average about 125. Proud of yourself, you tell your bosses. They say they’re aware of how great you’ve been doing and really appreciate your service. They even nominated you for Employee of the Month. You thank them, but suggest that maybe it would be fair if you got paid 25 percent more to reflect your increased productivity.

Your managers think about it and remind you that the economy is in a recession and many people are looking for work. They also invoke the company’s mission statement, about how innovative pasta sauce could one day change the world. Bongiovi Brand isn’t a food manufacturer; it’s a culture, an ethos, a creed, a way of life.

It’s hard to argue with any of that, and you’re willing to drop the matter and just get by with your current pay. But luckily your bosses end their spiel with a compromise: they’ll pay you $17 an hour, and if you keep up the good work, there’s a promotion with your name on it.

You can’t shake the feeling of elation. You’re so happy that your coworker Debra says to you, “Hey, you’re absolutely glowing!” And you tell her that’s because you just got a raise to $17 an hour. She hesitates for only a moment and then congratulates you—but something doesn’t feel right.

Later that day, you’re passing by the labeling department, and you see Debra crying. Everyone’s eyes at Bongiovi are always a bit watery as a result of the vast amount of curry incinerated on the premises, but this seems different.

“Hey, you didn’t happen to watch a 2009 sports drama written and directed by John Lee Hancock and featuring a gut-wrenching performance by Sandra Bullock?”

“Yes, but I’m actually crying because I’ve been working here for three years, and I only make $13 an hour.”

Bottling sauce was no harder than labeling it—you’re outraged by the disparity. You promise you’ll talk to management about it.

The next day you do just that, saying, “Listen, I know I’m kind of a favorite around here on account of my personality, but it’s really unfair that Debra is paid so much less than me for doing basically the same work.” Your bosses tell you that, actually, you aren’t a favorite—in fact everyone thinks you’re kind of weird. They explain that the difference in pay is based on the fact that Debra’s old job gave her $7.50 an hour, so she was started at $11 here, which was still a big improvement. Plus, she’s never asked for a raise the way you did.

All that information seems accurate, so you go ahead and ask if she can also receive a raise. Your managers say that they’d love to do that, but times are tough, and to be honest, Debra isn’t as productive as some of her coworkers. They can’t give everyone a raise. You learn that a big corporate rival has been winning market share by cutting labor costs and lowering the price of their sauce. “The best thing we can do for Debra is to make sure she has a job for years to come.”

You don’t see them budging, so you drop the matter and tell Debra you tried your best.

But what happened to Debra becomes a catalyst for change at Bongiovi. First, employees meet together after work to talk about how much they’re paid and what conditions are like at the plant. They care about the company, but they want to receive benefits like paid sick days. The meetings snowball, and eventually workers form a union.

The union helps things for a while, but the next few years are tough for the curry-flavored pasta sauce market. Competitors in India—a land of curry, tomatoes, and cheap labor—are well positioned to disrupt the industry. There are rumors of the company being sold or jobs getting outsourced, but management says nothing. Finally, Mr. Bongiovi addresses the speculation: we’re in it for the long haul, we believe in pasta sauce, but more than that we believe in people.

Things would have to change to restore Bongiovi Brand to profitability, but the union contract limits Mr. Bongiovi’s options. He loves his employees, but it’s sometimes necessary to saw off a leg to save a life. Without the freedom to unilaterally lay off redundant workers, Bongiovi thinks up another plan: he gets a line of credit from his son Jon and uses it to upgrade machinery in the factory.

At first you welcome the development—bottling pasta is hard work, and the new system will be semi-automated. If you turned out a hundred jars an hour before, you figured you could do two hundred now. But instead of making your life easier, the changes make your job more difficult. Your bosses are as friendly as ever, but they’re under tremendous pressure themselves. They say everyone needs to produce two hundred fifty jars an hour for the sauce to be priced competitively, then three hundred jars. The company even tries to find more time for you to bottle sauce—first by cutting lunch breaks and then by extending the workday an hour.

The union stops the latter, but the employees want to avoid disruptions and prove how productive American labor can be. Plus, it would look terrible for union leaders if a shop closed down just a few years after being organized—imagine how many workers at other companies would be discouraged from doing the same!

The result is that you feel helpless. Even before the more demanding work regime, you felt as though you didn’t have a say in how things were run and you got sick of being told what to do every day. You know your company is in a precarious position, but you also know that those in charge are getting paid fifty times more than you. Are they really doing fifty times the work? Couldn’t you figure out how to do their jobs too?

At the end of every day you’re physically and emotionally exhausted and unable to do the things outside of work you used to love: write, swim, take out loans in the name of Fred’s cat. You think about quitting, but without family or savings to rely on, it’s impossible.

Who put you in this situation? Jon Bon Jovi? Those curry-loving Indians?

THE ANSWER ISN’T who, it’s what: capitalism. Capitalism isn’t the consumer products you use every day, even if those commodities (wet wipes, tobacco, hair wigs) are produced in capitalist workplaces. Nor is capitalism the exchange of goods and services through the market. There have been markets for thousands of years, but, as we will see, capitalism is a relatively new development.

The market under capitalism is different because you don’t just choose to participate in it—you have to take part in it to survive. Your ancestors were peasants, but they weren’t any less greedy than you. They had their little plot of land, and they grew as much crop as possible on it. They ate some of it, and then they gave a chunk of the remainder to a local lord to avoid getting killed. Any leftover product they often took to town and sold at the market.2

But you, pasta sauce proletarian, face a different scenario. You might’ve said that you’re into locally sourced, sustainable food on your Tinder profile, but you don’t own any land. All you have is your ability to work and various personal effects that I originally listed here in great detail but have since been removed by my editor.

Now that’s not nothing. You’re an above-average student, a hard worker, and capable of thinking creatively and solving problems. But those skills aren’t enough—they don’t provide you with the stuff you need to survive. That’s where Mr. Bongiovi comes in.

By virtue of owning a place of work, a boss has something any would-be employee needs. Without land to sow, your labor power by itself isn’t going to produce any commodities. So you rent yourself to Mr. Bongiovi, mix your labor with the tools he owns and the efforts of the other people he’s hired, and in return receive a wage, which is really just a way to get the resources you need to survive.

The power imbalances are obvious when you enter into your employment contract. Though Mr. Bongiovi needs workers, he needs you as an individual employee less than you need grocery money. But that doesn’t mean that the arrangement isn’t mutually beneficial. Better to be exploited in a capitalist society than unemployed and destitute.3

You’re allowed to do almost anything you want on nights and weekends. Sure, you can’t break the law, but you’re living in a democracy and can theoretically influence those laws. But when you’re at the pasta sauce plant, you’re subject to the dicta of your bosses. They’re bound by state and federal labor regulations and even a union contract, but it still feels oppressive.

You endure, in part by telling yourself that reconciling yourself to authority is a necessary part of adulthood. But if you had a reasonable alternative to submitting to someone else’s power, wouldn’t you take it?

Your cousin Tito used to work at a Subway, but then he saved up and started a Hindu nationalist yoga magazine. Certainly, some people by virtue of chance or talent manage to go from workers to small business owners, who themselves employ labor. But that route can’t be taken by everyone—there would be no one left to hire! Without such luck or a trust fund to fall back on, you’re stuck subordinating yourself to capitalists who own private property and can make wealth out of your labor.

But that’s not to say that money is literally made from your sweat. Profit isn’t guaranteed—and entrepreneurial risk is one justification for capitalist profits. The pasta sauce you’re bottling has to sell for more than the direct cost of producing it, plus any overhead. After all that, if Mr. Bongiovi wants to stay competitive, he has to invest in new technologies and fix wear and tear on existing machines.

Under feudalism, it’s clear that a lord is exploiting a peasant—the peasant is doing all of the labor. Capitalism complicates matters: capitalists contribute to production as managers and conveners of labor, and their efforts are necessary to create new places of work. And, crucially, capitalists themselves are hostage to the market. Mr. Bongiovi is a nice man, and he wants to pay his workers double what they earn now, but he knows rivals will outcompete him if his labor costs are twice as high.

When he’s running his business, all the complexity inherent in Mr. Bongiovi—his compassion, his love of bird watching, his good humor—is necessarily subordinated to the pursuit of profit. But he also gets rich in the process, so don’t feel too sorry for him.

We can do better than this capitalist reality you’re stuck in.

IMAGINE YOU WERE born in Malmö, Sweden, instead of Edison, New Jersey. It is a slightly idealized version of Sweden, a mix of what social democracy actually accomplished in that country and what it could (or even should) have. The food is worse than in New Jersey—more preserved fish, less pizza. ABBA is no Bon Jovi. Your neighbor Frederick is naked a lot but otherwise seems okay.

When you were a baby, your parents were able to take paid time off work to take care of you. As a young person, you had access to a range of effective social services—free schools, great health care, affordable housing. After you finish university, you weigh your options. Should you do a PhD in art history (it’s free), apply for a state stipend to begin writing the Great Swedish Novel, or just find a job that seems interesting and see what happens next?

You pick up the Arbetet newspaper and read the classifieds. Unemployment is low, and there are many well-paid jobs to pick from. One, in particular, catches your eye. It’s an ad from a Swedish death metal band, which needs someone to keep its members fully stocked with spiked armor and goat heads for their next tour and to run its Twitter account.

You’re really good at social media—like, really. So naturally you get the job—20 euro an hour, 35 hours a week, with six weeks of paid vacation. You start working, and you find that things are okay. Your bosses are too busy making music to supervise you too much, so you have a lot of autonomy. Online ticket sales grow 12 percent in your first year, and you receive a nice raise, but you’re not really happy with the work. You quit.

In Sweden, unlike in New Jersey, more spheres of life are decommodified, meaning they’re taken out of the market and enjoyed as social rights. Even though you are unemployed—indeed, you would not have quit your job otherwise—you can rely on benefits, engage in civic life, and take some time to consider what to do next.

You could survive beyond a subsistence level on Swedish welfare, but you need an income to prepare for the next stage in your life: having a family, buying your own apartment, and so on. With that in mind, you take a job working at Koenigsegg, a high-performance sports car manufacturer.

After a few wildly successful quarters, Koenigsegg decides to expand into the consumer automotive industry. It builds a new factory, purchasing top of the line equipment. The company hopes it can win an advantage over its two main rivals, Saab and Volvo, by maintaining a smaller workforce and capitalizing on existing brand recognition among car enthusiasts.

Not one for physical labor, you apply for an inventory management position. You don’t earn much more than the assembly line workers, who are covered in the same industry-wide bargaining agreement. But you make 30 euro an hour, have plenty of vacation, and no longer need to listen to satanic mixtapes. It’s a good deal.

Your first year, the firm isn’t profitable, but it produces a well-regarded Volvo S60 competitor, and there’s hope that the company’s market share will grow. Your own morale wavers a bit. You don’t like your managers and what you perceive as a lack of freedom in the workplace. You’re paid well, and you have plenty of spare time, but spending sixteen hundred hours a year looking at spreadsheets isn’t exactly fulfilling.

At first, personal triumphs outweigh your professional malaise. You meet someone you want to spend the rest of your life with, and even though having children isn’t for you, you now have another reason to look forward to your frequent vacations.

Yet as you get settled at home, your work becomes more precarious. The company isn’t doing well—it produces quality cars, but there isn’t much consumer response. Management pours more money into marketing, but in doing so cuts into razor-thin profit margins. Kept alive by strong earnings from Koenigsegg’s traditional sports cars, the company decides to keep working toward a breakthrough in its mass-market operation.

You’re relieved, but the union contract that covers most of your workplace is about to expire. The agreement doesn’t only apply to your factory, or even Koenigsegg as a whole, but to much of the Swedish automotive sector. Even though Koenigsegg is struggling, other manufacturers are doing well, buoyed by export sales and favorable market conditions.

The national trade union federation takes an aggressive stance, basing its demands on the wages of a more efficient car manufacturer, Volvo. Equal pay for equal work is the federation’s principle. Saab and other, even more efficient companies than Volvo are easily able to pay the new wages and use the remaining profits to expand, but the increased labor costs spell disaster for Koenigsegg. You thought you were getting a raise; instead you can’t sleep at night. Sometimes it’s the thumping Eurodance coming from Frederick’s parties keeping you awake, but more often it’s your fears about your future.

Those fears are soon realized. Koenigsegg decides to halt production on its Volvo S60 competitor. The company survives, but it can’t accommodate its entire existing staff. Your severance is generous, but it’s only enough to keep you going for a year.

If you were a white-collar worker in America—much less a humble bottler of curry pasta sauce—you’d be in trouble. As a Swede, however, you land on your feet, owing to the generous welfare state. More important than the unemployment assistance, you and your other laid off coworkers are provided with state-funded retraining. The companies that survived the wage hike are investing in labor-saving technology, but they’re also expanding, meaning there are new jobs to fill.

What now? Maybe you end up working at Volvo, in a more senior position even. It doesn’t solve all of your problems; you’re not content with your life in every way. But you’re living in the most humane social system ever constructed. For a species that spent the better part of its existence hiding in trees from predators or huddled for warmth in caves, you could do worse than social-democratic, only partially fictional Sweden. But is there another alternative, one superior to our idealized social democracy?

IT’S HERE THAT you have to start using your imagination. Say you’re once again a pasta-sauce bottling New Jerseyan, and that the state is the epicenter of a radical political upheaval. Your problems can’t be solved through action at the Bongiovi plant alone, but there’s hope for change through a broader movement.

That struggle goes national with its rhetoric of democracy and fairness. Soon, a new left-populist movement fronted by Bruce Springsteen wins the presidency and a majority in Congress (Bon Jovi sticks to music, because he has too much respect for his craft). With the help of a rank-and-file resurgence in the labor movement, the president and Congress usher in the kind of reforms your doppelgänger in Sweden already enjoys. Health and education become social rights; child care and housing are made affordable.

Social democracy is so good that even Fred doesn’t mind working at a public hospital. But not everyone is pleased. A lot of people benefited from the old system—the corporate health care industry, for example, put up a mighty struggle when the US National Health Service was created, and is still trying to make a comeback by providing “personalized” outpatient services. And the economy is still driven by private enterprise. Capitalists resent the higher taxes they have to pay, don’t want to comply with new environmental regulations, and hate dealing with more empowered and restive workplaces.

Especially during downturns in the business cycle, capitalists can make a credible argument to voters: the whole economy only works if we’re making money, and we’ll only take risks in bringing new products and services to market if there’s a large enough reward to justify it. Plus, those bankers you keep handcuffing give us the financing we need to keep the whole machine humming.

Luckily, for most of the next decade, the new working-class political coalition—labor unions, feminist and anti-racist social movements, environmental activists—coheres a political program capable of beating back the capitalists. Still, there are divisions among Mr. Springsteen’s supporters. Some, like The Boss himself, want to preserve gains already won by making tactical concessions to capitalists. With a baseline of profitability protected, he and like-minded politicians argue, a segment of the elite can be persuaded that they benefit more by sticking with American social democracy than closing up shop or moving abroad. Others are less compromising, but though they push the system to its limits, they don’t believe it can be transcended. They settle for as much socialism as capitalism can take, supporting cooperatives and helping enlarge the public sector to mitigate the power of big corporations. Finally, there are radicals who want to break from capitalism entirely and create an even more democratic and egalitarian society.

These ideas and debates swirl around, while circumstances provide an opening for the radicals. Not only does a sizable minority of the nation make clear a desire for more left-wing reforms for ideological reasons (opposition to hierarchy and exploitation, even in a tempered state), but others come to support the socialists for practical reasons. You’re among the latter, believing that to even preserve the gains already made, capital flight and the continued political resistance of outnumbered but still powerful elites need to be taken on directly.

The nation is convulsed by strike waves matched in their intensity by owner lockouts. Social movements make heard long-muted demands for justice and equality, and people entirely new to politics hit the streets. Workplaces are occupied, and bosses are even kidnapped by radicalized workers. Even Fred finds a socialist group willing to have him (the six-member International Workers’ Committee for the Sixth International). Religious organizations and others concerned with the instability call for a return to law and order.

But in the end, a socialist coalition has a mandate to change society. It does not have a precise blueprint, and there will be need for improvisation and new thinking. But it does have the benefit of both the recent lessons of Springsteenist-left governance and those from the often tragic twentieth-century experience of socialism in power. History doesn’t usually offer second chances, so what would we do with one?

FOR YEARS PRIOR to this moment, there have been arguments within the modern American socialist movement—of which you are now part—about what exactly we oppose in capitalism and what we can live with. Capitalism is a social system based on private ownership of the means of production and wage labor. It relies on multiple markets: markets for goods and services, the labor market, and the capital market.

The left wing of the Springsteenist movement opposes private ownership of production and wage labor because of the power it gives some people over others. Its members believe socially created wealth shouldn’t be privately expropriated. Where the movement stands on markets is less clear.

Outside of theory, there’s no such thing as a “free market”—capitalism requires both planning and a regulated market. But the question about what role each would play under socialism is an open one. You spend long nights eating Hawaiian pizza and discussing it with Fred. As a doctor who sees how well the government-run health care system works, and as an avid SimCity 2000 fan, Fred proposes that markets can be done away with and replaced with central planning. In this system, regional or national planners decide what the economy should produce and then ask firms to turn out a certain amount of goods. They might have discretion in how they do so, but they have to hit their quotas.

You bring up the failure of that system in the Soviet Union. But Fred insists this will be different. Unlike in the old USSR, civil society would be free, and the plan could be formed democratically.

You’re skeptical, as you know that in the past planned economies went hand in hand with authoritarianism and corruption. Beyond that, they had trouble with “informational” problems. Backward countries using command economies were able to rapidly industrialize. Yet problems grew over time, as more and more goods had to be produced, all of which required prices to be set by planners without the range of consumer feedback that markets provide.

These planned economies had “strong thumbs, no fingers”: they were great at routinized tasks like carrying out vaccination campaigns, educating citizens, or mass-producing tanks, but couldn’t adapt to local conditions or unexpected changes.4

Consider a commodity like an iPhone. It is composed of hundreds of parts, each requiring dozens of raw materials, all of them mined, produced, and transported by thousands of people. How would we coordinate all of them? Now multiply that dilemma to an almost infinite combination of consumer preferences, goods, and services.5

“Why wouldn’t factory managers wastefully use raw materials, requesting more than they needed for production, out of uncertainty, like they did in the Eastern Bloc?”

“Look at Walmart and Amazon!” Fred counters.

“I thought you ‘only shopped local,’” you reply.

But he has a point. If Walmart was a country, it’d have a larger GDP than the whole of East Germany in 1989, and much of its activity is consciously planned, without crippling inefficiencies.6

You remain skeptical, but reply that even if new technologies solved calculation problems and markets could be simulated and responded to by planners and producers, incentive problems would still exist. In a condition of relative scarcity, and with robots unable yet to do all the work for us, wouldn’t we need inefficient firms to fail? Wouldn’t we need to compel each other, in some way, to innovate and work productively? Markets already have answers to these questions.

Yes, a democratic planning board could, with oversight from civil society, close the worst firms and provide perks to the most efficient workers, but this process seems vulnerable to political lobbying or worse. As you see it, in Fred’s idealized version of central planning, too much seems to be riding on the general population developing a socialist consciousness.

Still, among some socialists, more democratic, local, and nonmarket ways for people to communicate their consumer preferences are being discussed. Neighborhood councils could lay out their consumption needs and reconcile those demands with what democratic workplaces are willing and able to produce. But these councils run the risk of being tedious, the sort of things only people who like endless meetings would enjoy. That’s not to mention the complexity of trying to negotiate among all parties in such a system.7

Your debate with Fred plays out across society. On ideological grounds, it’s legislated that workers should control their firms and that they should no longer receive a wage (though there would still be minimum incomes based on job classification), becoming real stakeholders in their companies instead.8

Two key markets under capitalism are thereby done away with: the traditional labor market and capital markets. But markets for goods and services remain. Too many informational problems exist for them to be done away with. Companies will also still have to compete with each other—inefficient firms will collapse (though the fall for individual stakeholders in a firm would be cushioned by the welfare state, even more so than it was in our idealized Sweden).9

These measures provoke turmoil as capitalists muster desperate acts of resistance. But in the end banks are nationalized, and the state takes over all private firms. You see firsthand how things play out at the pasta sauce plant.

YOUR WORKPLACE HAS been more stable than most. Since you had a union, wages at the firm were already higher than industry average before Springsteenism, so Bongiovi had less trouble dealing with the new national living wage legislation. Only three days were lost to work stoppages in the past year, a miracle considering the turmoil elsewhere.

The cooperative sector was at first just a minor competitor to the private, capitalist one. Congressional legislation was passed to socialize shuttered businesses or those already occupied by workers. But the policy proved popular, and it was a way to erode the power of capitalists still trying to roll back reforms. It was expanded to firms employing more than fifty workers, Bongiovi’s included. Along with other shareholders, he was expropriated with compensation on a prorated basis. Indeed, he received more than others by agreeing to cooperate with the transition.

It wasn’t that Mr. Bongiovi was supportive of the process; he was simply resigned, worn down by years of inroads into his property rights. With his payout, he was able to retire comfortably and reconcile himself to the new order. Other capitalists were more resistant. They were free to organize in civil society, but moderate social democrats constituted a far more powerful opposition to the governing radicals. A tiny minority of elites, including an eccentric George W. Bush grandson, even sincerely adopted the socialist cause.

It’s May 1, 2036, and things have been slowly shifting around you for years. But on this day, everything will decisively change. The final shares of Bongiovi Brand pass into state ownership. Don’t worry, though: you’re not trading a set of unelected private managers for distant government bureaucrats. Collectively you and your coworkers now control your company. You’re more like citizens of a community than owners. You just have to pay a tax on its capital assets (the building and the land it’s on, machinery, and so forth), in effect renting it from society as a whole. (To preserve the value of the capital stock in your care, a depreciation fund must be set up for repairs and improvements.)10

Your tax goes into a public fund, which invests in new endeavors. More about that later. But the tax you pay also solves the problem of different production processes having wildly different capital-labor ratios. If workers simply collectively owned their firms’ capital, those in capital-intensive industries would earn far more profits than those in labor-intensive ones. Having different “rents” prevents that. You also have to pay a graduated income tax, as you did before, on the income you take home. This funds social services and other state expenditures.11

A meeting is convened at the start of the day, and everyone looks differently at the worn-down factory that you came to despise but that now belongs to you and your colleagues. The sense of pride quickly subsides as practical business begins.

Though new laws assert that everyone should participate in management on equal footing, this is implemented in various ways across companies. Because it is a larger enterprise, a representative system of governance is approved at Bongiovi. Workers from each department elect delegates to a proportionately elected workers’ council. This council has oversight over the entire business and is tasked with appointing management, including a managing director.

You get yourself elected as a council member and, in choosing the new management, vote for a mix of experienced middle managers and others drawn from the shop floor. Most have already been trained, while the rest have demonstrated themselves to be quick studies. Those selected have a three-year term that can be extended, though they’re required to spend at least two weeks a year on the shop floor.

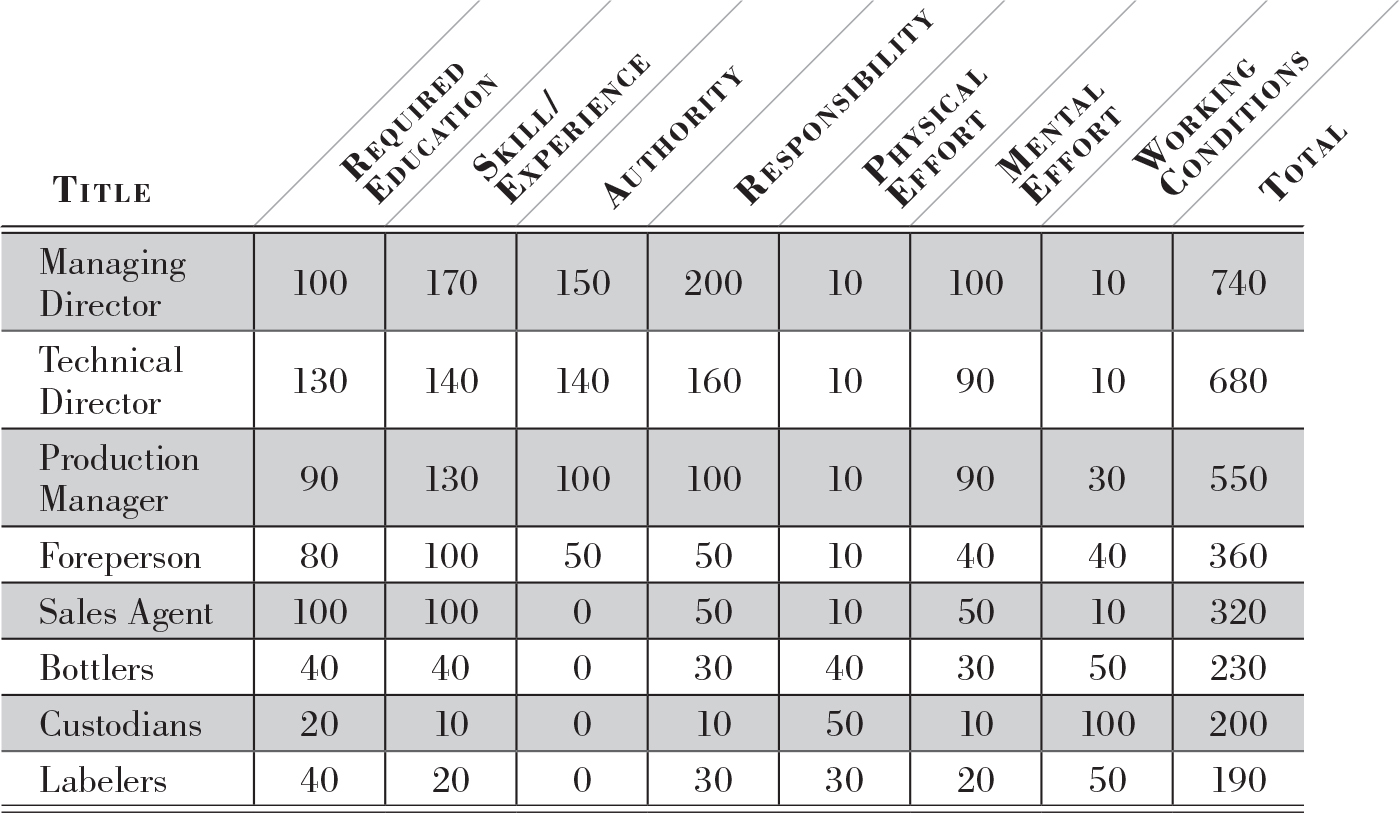

Collectively, the workers’ council also writes a new firm-operating agreement and suggests pay differentials, subject to approval from the general membership and to annual revision. In the new system, workers don’t get a wage; instead they get a share of the profits. However it is decided that people should receive more compensation for roles that involve more stress, responsibility, or training. On the other side of the spectrum, jobs that are seen as undesirable are paid well enough to ensure they’re adequately staffed. Here’s a compensation table you help come up with:12

It looks a bit arbitrary, but the scale was set after extensive discussions and study. Along with the operating agreement, it is approved by 70 percent of the workers. Before Springsteenism, the average CEO-to-worker compensation in the nation was 354:1; after, it dropped to 89:1. At your workplace the most extreme differential is now 4:1. It’s similar at others, as well.

Work gets better, but it doesn’t feel as if something monumental has happened. You get paid more, you have a bit more say in what goes on at work, your job is secure, your managers are responsive, there’s more office camaraderie, but still, at the end of the day, everyone just wants to leave.

That’s not because things are bad at work, but because things are better where they are going—to homes no longer ripped apart by financial burdens, where household work is more equally shared (better-paid women have the power to negotiate a different compact with their spouses), and to communities where entertainment, sports, and leisure are accessible to all. It’s a transformed world, where life isn’t perfect, but where millions have more spare time and less stress.

This newfound freedom comes from expansive social services and public guarantees. Under capitalism, the heads of enterprises constantly fought back against social reforms. But now these policies are in sync with the values of wealth-generating, worker-controlled firms.

Of course, just as there are still plenty of social problems to confront, there are still issues at work. Receiving a share of profits rather than a fixed wage motivates most people at the firm, but a few of your colleagues struggle. Your bottling partner Kiran shows up late often and neglects important assignments.

You gently nudge him to pick it up, but the stakes don’t seem very high. Kiran is a friendly person, and how much damage can one worker do? Yet management takes notice of his behavior. One day, Kiran is written up for safety violations, caused by his laxness. He resents being told how to do his job, one he’s clearly tiring of.

“Capitalism is the exploitation of person by person; socialism is the exact opposite,” he laments.

It’s understandable that someone would be sick of work that, no matter the degree of worker control, is still work. But from the unit supervisor’s perspective, she has the duty to make sure everyone is doing their share. And unlike management back when the plant was privately owned, if someone thinks a supervisor is acting improperly or wants things to be run differently, they have democratic recourses to do something about it.

In this case, Kiran is clearly at fault, and his behavior doesn’t change. He’s not dehumanized, but rather dealt with much as he would be in a highly unionized social democracy. Kiran is protected from discrimination and wrongful termination by robust state legislation. He goes through a progressive disciplinary process—first comes a warning, with concrete suggestions for improvement, then a suspension with pay, then finally, dismissal with three months of severance.

It’s when Kiran leaves Bongiovi that the difference between New Jersey 2019 and New Jersey 2036 is most obvious. In the past, Kiran would’ve been desperate without work, his entire existence dependent on convincing an employer to give him another chance. Now, he can get by on the state’s basic income grant and supplement it by taking a guaranteed public sector job, doing socially necessary work. He has access to all the core necessities of life, and when he decides to become a barber, it’s his choice.

A real choice, not a “work or starve” choice. People don’t merely have a voice in their workplace; they have the freedom to leave. Why don’t more people decide to opt out of the labor market? The chance to make more money, which could allow them easier access to consumer goods or exotic travel, plays a role. But others truly take pride in their jobs and enjoy collaborating at work.

Meanwhile, back at Bongiovi, you see that plant democracy is more than symbolic. Back in 2019, labor-saving technology had everyone working faster. Now, when new technology is brought in, your coworkers have a different calculus. If they can produce 20 percent more per employee, why not decrease the workweek to twenty-eight hours? (For all sectors, legislation dictates the required workweek cannot exceed thirty-five hours.)13

There is still market competition, and firms still fail, but the grow-or-die imperative doesn’t apply when your enterprise’s goal is no longer to maximize total profits but rather to maximize profit-per-worker. And instead of a race to the bottom, there’s pressure to make sure janitorial and other “dirty jobs” are well compensated. In time, many of these tasks will be automated. People used to fear that machines would bring about mass unemployment, but now you and most others look forward to the social impact of technological innovations.14

AT THIS POINT, you’ve been bottling sauce for twenty years; you’ve seen the firm adapt to new consumer preferences and maintain a steady market share for much of that time. Though the future looks bright, you decide to do something else with your life. Through work rotations and meetings, you have a sense of Bongiovi’s entire operation and can probably run for a management role. But the whole industry kind of bores you. You didn’t get into the curry pasta sauce hustle because you loved the game. Back in 2018, you just needed some money.

Now, with half your life still ahead of you, you have options. One day, while hanging out with the now retired and increasingly tolerable Fred, you come up with a design for medical utility suspenders. How would you go about securing capital for a new venture under socialism?

Unlike in capitalism, start-ups aren’t fueled by private investment, but rather the capital goods tax mentioned earlier. The funds are invested into the economy in a variety of ways. National planning projects—like renovating the energy grid or high-speed rail networks—are the first priority. What’s left is given to regions on a per capita basis. Under capitalism, people were forced to abandon cities to chase jobs in expanding markets. Now people still move around, but they won’t be compelled to do so by capital flight.15

The funds are channeled by regional investment banks (public, of course) that engage in more local planning and then apportion the rest to new or existing firms. Applicants are judged on the basis of profitability, job creation, and other criteria including environmental impact. If there aren’t enough profitable enterprises starting up or expanding, some of the money can always be directly transferred back to taxpayers to stimulate demand.16

All of these outcomes entail trade-offs, and these trade-offs are political decisions. Citizens in one area might pursue a different policy balance than those in another, and adjustments would be made constantly, with successful experiments emulated.

The partners you bring into your firm will be just that—they’ll be shareholders, not your employees. But since you’re starting the firm, you have some discretion in setting the initial operating agreement. In order to attract workers, you need to keep income differentials relatively flat. But in the end it’s worth it to you—you and Fred are rewarded for your new invention with a small amount of state prize money, and you do end up earning more as an elected manager at your new job than your old one. But what’s more significant is the fact that your suspenders catch on and become a fashion statement outside of the medical profession. You’ve finally left your mark on the world.

The decades pass on, and you eventually retire, cared for by the society that you contributed so much to, while enjoying the love of friends and family. Looking out at the broader world, you see that things are as dynamic as they were in 2036. With more decisions in the hands of ordinary people, civil life is full of political debate and new ideas. Even distributional questions are still not settled: a center-right party advocates for more market incentives and a reduction in the basic income; a center-left party questions traditional metrics of growth, proposing a happiness index instead; an internationalist left calls for more vigorous support for the workers’ movement abroad and more extensive democratic planning at home. And yes, there is a Right calling for the restoration of capitalism, but its support diminishes over time, much like monarchism slowly lost supporters in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

It’s a starting point, then, for a better society, not necessarily a happy ending. You’ll live long enough to see whether or not, as abundance and automation spread, there will be less need for material incentives. You’ll see whether markets can be eroded further, and you’ll ask, as many others will, if that would be desirable.

There’s a greater sphere for participation, as democracy has been radically extended to the social and economic realms. That carries with it some risks. Struggles against racial disparities and further battles against the sexual division of labor will be needed. Informed citizens will have to watch out for new forms of exploitation and oppression and small inequities spiraling into bigger ones. But these are the perils of democracy, and a small price to pay for living in the world’s first truly democratic society.

THOUGH HARDLY APPROACHING “rich Instagram kids on a yacht” levels of privilege, in all these examples you’re doing okay to begin with. Even under capitalism you enjoyed a solid education and found employment. You even had leisure time. Millions today living in the richest societies in history, however, can claim no such luck.

For these people—much less billions in the Global South—the struggle for reform is urgent. Capitalist growth has produced wonders, and, especially when harnessed by strong states, it continues to. But it also has proved itself to be no natural friend of democracy, civic freedom, the environment, or the lives of those it doesn’t have a profitable way to exploit.

At its core, to be a socialist is to assert the moral worth of every person, no matter who they are, where they’re from, or what they did.17 With any luck, future generations will look back at the time when life outcomes were accidents of birth with shock and disgust, the same way we look back on more extreme forms of exploitation and oppression—slavery, feudalism, and so on—that have already been done away with. If all human beings have the same inherent worth, then they must be free to fulfill their potential, to flourish in all their individuality.

In order to realize this kind of expansive freedom, we need to guarantee at least the basics of a good life to all. And given the opportunity to thrive, people can contribute to society and create the conditions in which others can do the same. Freedom for working people today, however, means limiting the freedom of those who benefit from the inequities inherent in class society. Socialism is not so much about trading in freedom for equality but rather posing the question, “Freedom for whom?”

Now imagine what a change it would be for a young black American to grow up in a society where they didn’t have to settle for the worst schools, the worst health care, the worst jobs, or possibly be subjected to the worst carceral system on Earth. Imagine what it would mean for women if they were more easily able to leave abusive relationships or escape workplace harassment with the help of strong welfare guarantees. Imagine our future Einsteins and Leonardo da Vincis liberated from grinding poverty and misery and able to contribute to human greatness. Or forget Einstein and Leonardo—better yet, imagine ordinary people, with ordinary abilities, having time after their twenty-eight-hour workweek to explore whatever interests or hobbies strike their fancy (or simply enjoy their right to be bored). The deluge of bad poetry, strange philosophical blog posts, and terrible abstract art will be a sure sign of progress.

But if we’re already in our idealized version of Malmö, Sweden (one that might have been close to reality back in 1976), why would we want to go further? A good social democracy checks a lot of the boxes mentioned above, and presumably where it falls short it could be improved without completely doing away with private ownership.18

There is an ideological motivation for a more radical socialism, the moral idea that the exploitation of people by other people is a problem in desperate need of a solution. Capitalism both creates the preconditions for radical human flourishing and prevents its ultimate fulfillment. For socialists, to the extent that some hierarchies linger, they have to be constantly justified and held in check. Think about the authority a parent wields over a child. By most people’s lights (including most socialists’), this authority is reasonable, but it is also regulated by law. You can’t beat your child, and you can’t keep them out of school or prevent them from leaving home when they become adults.19

Today almost everyone would agree that extreme forms of exploitation, like slavery, should be prohibited. The socialist argues that wage labor is in fact an unacceptable form of exploitation, too, and that we have alternatives that will empower people to control their destinies inside and outside the workplace. But even I have a hard time imagining that the abstractions of ideology will be enough to encourage a risky leap from a humane social-democratic world into an unknown socialist one. If it happens, we will probably only be driven down the path to socialism by practical necessity, by the day-to-day struggles to preserve and expand reforms.

Indeed, as we’ll see in the historical tour of socialism that makes up the first part of this book, social democracy bolstered the power of labor to degrees few thought possible, but still left capital structurally dominant. With the power to withhold investment, with the economy still reliant on their profits, capitalists were able to hold democratic governments hostage and roll back reforms. Their economic power translated into enduring power over the political process.

Social democracy is a step in the right direction, then, but ultimately not enough, owing to its vulnerability. Of course, we should be so lucky to find ourselves living under social democracy today. Neoliberalism is the watchword of our age. Most people are saddled with debt, have few job protections, can’t comfortably afford health care and housing, and don’t believe that their children will fare any better than they do. In this new gilded age, they’re unwilling philanthropists, subsidizing the lavish lifestyles of the rich.

Socialism can do better—but I don’t claim that it can fix everything. Even under socialism life would still be filled with plenty of lows. It will still sometimes feel overwhelming, you’ll probably get your heart broken, and people will still die tragically from accidents and suffer bad luck. But even if we can’t solve the human condition, we can turn a world filled with excruciating misery into one where ordinary unhappiness reigns. Maybe we could even make some progress on that front. As Marx put it, with our animal problems solved, we can begin to solve our human ones.20

BOOKS LIKE THIS often start by telling you, the reader, what’s wrong with the world today. For much of capitalism’s history, radicals have been sustained less by a clear vision of socialism than by visceral opposition to the horrors around them. Instead of making the case for socialism, we made the case against capitalism. I have tried to do something different by presenting what a different social system could look like and how we can get there.

Naturally, it’s easy to compare an existing, complicated society with one that only lives in our imagination. In Marx’s day, utopian socialists did little but write “recipes for the cookshops of the future.” But today, it’s a crucial task to win people over to the idea that things can be different, even if we can’t precisely say what future generations will decide to construct.21

The first part of this book charts the history of socialism from Marx to the present day. Every would-be socialist, and anyone interested in socialist ideas (even if only to know how the other side thinks), needs to engage with the many threads of this story. Often maligned as utopians with eyes only on the future, socialists in fact have from the beginning been students of history. Today’s socialists must follow in the same tradition.

In a matter of decades, socialists went from fringe believers to masters of much of the world. I tell that story, from the emergence of capitalism and the creation of a working class, to the maturation and then implosion of working-class politics in the parties of the Second International. Then there’s the rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia. The authoritarian collectivism their experiment produced not only claimed millions of lives but came to be associated with any challenge to capitalism. I do not shy away from considering what went wrong in the Soviet experience, which jettisoned the democracy and civil liberties at the core of the socialist dream.

Elsewhere, socialists did eventually win power in capitalist democracies, constructing societies that allowed millions to live decent, fulfilling lives. Despite not being able to bring about a successor system, their reforms had radical implications. We’ll see why social democracy failed but also how it opened up new avenues to a socialism beyond capitalism. We’ll consider checkered attempts by those in the Third World, namely Chinese revolutionaries, to use socialism as an ideology of national development. Finally, we arrive at socialist politics in the United States, which have appeared episodically and supported important reforms but have not taken root as they have elsewhere.

The twentieth century, for both good and ill, left socialists with plenty of lessons. The history that follows is not comprehensive but selective, aiming to draw out those lessons, from both the revolutionary and the reformist wings of socialism, for the present day. We can learn from this history that the road to a socialism beyond capitalism goes through the struggle for reforms and social democracy, that it is not a different path altogether. We can also learn that we can’t rely on the professed good intentions of socialist leaders: the way to prevent abuses of power is to have a free civil society and robust democratic institutions. This is the only “socialism” worthy of the name.

Today there is much talk of “democratic socialism,” and indeed I see that term as synonymous with “socialism.” What separates social democracy from democratic socialism isn’t just whether one believes there’s a place for capitalist private property in a just society, but how one goes about fighting for reforms. The best social democrats today might want to fight for macroeconomic policies from above to help workers. But while not rejecting all forms of technocratic expertise, the democratic socialist knows that it will take mass struggle from below and messy disruptions to bring about a more durable and radical sort of change.

In the second part of this book, I discuss the world today and why there are new opportunities for this better sort of socialism to take root. As we’ll see, Britain’s Jeremy Corbyn and the United States’ Bernie Sanders have pursued a “class struggle” social democracy, unleashing popular energy that has revitalized the Left as a whole. I offer a tentative strategy for taking advantage of this unexpected second chance and explain why the working class can still be an agent of social transformation.

Even in the bleakest chapters in this book, an urgent commitment should be clear: if there is a future for humanity—free of exploitation, climate holocaust, demagoguery, and the war of all against all—then we must place our faith in the ability of people to save themselves and each other.