ONE

![]()

A Tangled Inheritance

SOME OF MY earliest memories are of Temple Sowerby House. I remember the line of tarnished servants’ bells in the passage outside the kitchen door, the tap tap tap of buckets catching rainwater that dripped through the ceiling, the mint-green porcelain of my grandmother’s 1930s bathroom suite; but most vividly of all, I remember the gallery. This was the light-filled corridor up narrow stairs at the back of the house, with three windows looking down on to the overgrown walled garden below. As a small child, on wet days – not unusual in this part of north-west England – I would run up and down the gallery, stomping on the floorboards, pausing only to examine the zoological specimens on display, which included two stuffed crocodiles, a rhinoceros horn and a narwhal tusk. I was particularly drawn to the glass domes filled with birds, their feathers all the colours of the rainbow, although I had no idea where they might have flown from.

This was the early 1970s, by which time dry rot was consuming the Georgian part of the house. In the entrance hall, burnt-orange brackets of fungus bloomed like a ghoulish botanical wallpaper; in the drawing room, many of the floorboards had been pulled up, and much of the ceiling plasterwork had fallen down. My grandparents, Jack and Evelyn Atkinson, had long since retreated to the rear of the building, the original seventeenth-century farmhouse on to which the handsome front wing had been added during more affluent times. Here the parlour, with its low oak beams and red sandstone chimneypiece, and the kitchen, with its blue enamel range cooker, were the only rooms where they managed to keep the damp remotely at bay.

Jack was quite unfit to be the custodian of such a property. When he moved up to Westmorland from London in the late 1940s, having inherited the 200-acre family farm, he was nearly sixty. Too old and impractical to take the land in hand himself, instead he let it out, and was too soft-hearted to put up the rent for twenty years. As a result, my grandparents were always strapped for cash and invariably in arrears with local tradesmen, who made the classic mistake of confusing gentility with liquidity. They reckoned themselves too poor to have slates replaced or gutters cleared – which is how it came to be that water was coursing through the roof and walls. Even so, every Christmas they ordered a hamper from Fortnum & Mason, London’s most exclusive grocer, to make sure they were adequately provisioned during the festive season.

Jack exuded old-fashioned charm; at eighty, as he ambled about the village, tipping his hat to the neighbours, his handsome features were still apparent. Evelyn, on the other hand, had the air of someone constantly disappointed by life, and there was little that did not provide the raw material for complaint. The pair of them rattled around the house, which was largely empty, since most of the contents – beds, tables, sofas, pictures, carpets – had been sold off long ago. They kept strange nocturnal hours, rarely going to bed before three in the morning, and rising in the early afternoon. Sometimes, after breakfast, Jack would wander down to the village shop, only to find that it had already closed for the day. Evelyn, who was obsessed by security – not that there was much worth stealing – roamed the corridors with a big bunch of keys, locking up behind her wherever she went.

My father John, their adored only child, used to dread visiting Temple Sowerby; as the next in a long line of Atkinsons who had inhabited the village for at least four hundred years, he was all too conscious that the house would one day pass to him. Already his parents had started offloading their money problems on to him, often sending begging letters that made him feel guilty and miserable. His salary as a book editor living in London barely met his own needs.

In October 1966 John married my mother, Jane Chaytor, who provided a much-needed burst of energy and hope. She took control of her in-laws’ chaotic finances and arranged for a review of the farm rent, which at a stroke doubled their income. She paid their bills – they were amazed to find that the butcher would look them in the eye again. It was she who had the range cooker installed in the kitchen. Jack was captivated by his pretty, practical daughter-in-law, making it all too clear to Evelyn that she was exactly the sort of woman he wished he’d had the good fortune to marry.

A few weeks after I was born, in June 1968, Jack wrote to my father: ‘Dear Old Boy, we were delighted with the photos; please thank Jane very much for them. Richard, understandably, didn’t show much interest in the proceedings, but you looked, also understandably, as if you were holding the most precious bundle in the world. Quite right too.’[1] Two months later my parents took me up to Westmorland to be baptized in the church at Temple Sowerby.

AROUND THIS TIME, my father started waking in the night with a dull ache in his gut, and hospital tests revealed a tumour; but following surgery his prognosis seemed quite positive. My sister, Harriet, was born in the spring of 1972. That autumn, after four years of good health, my father developed jaundice; the cancer was back. Soon he was too weak to climb the stairs, and a bed was made up for him on the ground floor of our terraced house in Pimlico. He was a sociable man, and over the following weeks a succession of friends and colleagues came to say goodbye. He died at home on 24 February 1973. He was thirty-eight. His funeral took place a few days later, on Harriet’s first birthday.

Three months later, Jack too was dead, and buried alongside his son in the graveyard at Temple Sowerby. Suddenly, following the custom of primogeniture, Temple Sowerby House was mine – not that I knew it. As for the farm, the line of succession was not so clear. Under the terms of my great-grandfather’s will, written in the 1920s, Jack had been left a life interest in the property, which allowed him to enjoy the income it generated but prevented him from putting it up for sale. This same document stipulated that on Jack’s death, the farm would pass to his eldest son or, failing that, his eldest daughter – but no such person now existed. What the will did not anticipate was the possibility that Jack might leave grandchildren who could inherit the farm. So instead the estate was split equally between the principal heirs of each of my great-grandfather’s three children: the niece of Jack’s elder brother George’s late widow; the son of Jack’s younger sister Biddy in South Africa; and me. In short, the premature death of my father, and the restrictive language of my great-grandfather’s will, meant that the farm passed out of the family’s hands.

The bleak practicalities of probate fell to my poor mother. Her first instinct was to hold on to the house, so I might one day have a chance of living there; but given that she had no money for repairs, the idea presented formidable difficulties. The most obvious solution was to pull down the rotten eighteenth-century wing and retain the relatively habitable oldest part. Following the local council’s rejection of her planning application, however, my mother realized that only one viable option remained. After moving my grandmother into sheltered accommodation, and suffering many sleepless nights, she called in the estate agents. It was a conclusion for which I will always be grateful.

Temple Sowerby House was by no means an easy sell. Quite aside from its state of semi-dereliction, it had another major drawback. The busy A66 trunk road that crosses the Pennines, linking Penrith and the M6 motorway in the west to Scotch Corner and the A1 in the east, cut straight through the village, not twenty yards from the façade of the house. Just the thought of a thousand lorries thundering past every day was enough to deter most buyers. But finally, in the summer of 1977, the Atkinson family home was sold to a developer who envisioned for it a future as a hotel – the passing trade, for once, counting in its favour.

Apart from the crocodiles, which she banished to a Penrith saleroom, my mother put the contents of the old house into storage; in particular, the three oak court cupboards in the gallery, each carved with the year of its making (1627, 1658 and 1729), which were far too bulky to fit into our small London home. The Atkinson chattels also included two large blanket chests, two broken-down longcase clocks, a well-worn rocking cradle, a spinning wheel and a set of Chippendale mahogany dining chairs, as well as a bookcase full of well-thumbed eighteenth-century volumes on a variety of practical subjects, and heaps of Chinese blue and white porcelain plates, bowls and soup tureens, many of them chipped. Just as I am relieved that my mother got rid of Temple Sowerby House, I’m thankful she kept this motley assortment of objects – baggage they may be, but they are still my most treasured possessions.

My dad’s death was the defining event of my childhood; not a day went by when I didn’t somehow sense his absence. Because he had been an only child, there were no aunts or uncles to pass on Atkinson stories to my sister and me. (In fact, except for our elderly bachelor cousin in South Africa, who sent us a large, oozingly sticky box of crystallized fruits every Christmas, we were unaware of having any relatives at all on our paternal side of the family.) After the house at Temple Sowerby was sold, the only reason we had to stop off at the village – passing through in the car en route to holidays in the Lake District – was to place flowers on my father’s and grandparents’ graves. Although these visits lasted a matter of minutes, they loom large in my memory. Every time, as we approached, I would feel fluttering excitement; and every time, as we drove away, I would feel sadder and emptier than before. Temple Sowerby came to represent all that I had lost during my early years; it was a place where it seemed I would always have unfinished business.

WHILE I WAS growing up, people who had known my dad often told me how much I resembled him, so it was perhaps inevitable that I would follow him into a career in book publishing. In many ways I felt blessed to be like him, since it meant I always carried him around with me; occasionally it felt like a curse. In my thirties, I suffered from digestive problems that caused me much discomfort. Bowel cancer can run in families, and for several years I was sure that I was destined to follow my father to an early grave. When I finally celebrated my thirty-ninth birthday, in 2007, it felt as though a weight had lifted, even as another pressed down; for that year Sue and I finally grasped, after seven years of marriage, that we would never have children of our own. This was a fate I had not imagined, and I felt rudderless, as though robbed of my purpose. My emotions turned raw and unpredictable; for no clear reason, I would break down crying in the street. I now realize I was mourning the sons and daughters I would never know.

While my contemporaries looked to the future, and threw themselves into the all-consuming business of raising families, I turned towards the past, and decided that perhaps it was time I found out about those who had preceded me. One day, while rummaging around in my mother’s house, I discovered, gathering dust on top of a cupboard, a scruffy old cardboard box which contained several hundred letters tied up in tight bundles with pink legal ribbon. Most of them were addressed to a ‘Matthew Atkinson, Esq.’ at Temple Sowerby and dated from the first decades of the nineteenth century. At the same time I came across a family tree, mapped out on a roll of graph paper about twenty feet long, which traced the Atkinsons back to the late sixteenth century. It was in my father’s handwriting – I guessed he must have compiled it some time before his marriage, since right at the bottom I noticed he had added my mother’s name, and then mine and Harriet’s, in slightly different shades of blue-black ink. Looking over past generations, I soon realized how presumptuous I had been to assume that I would have children; while some branches of the family tree were ripe with offspring, others withered to nothing. Below the names of all those whose marriages had not borne fruit, my dad had written the sad little genealogical acronym ‘d.s.p.’ – decessit sine prole, the Latin for ‘died without issue’.

I found the prospect of delving into the box of letters quite daunting, but one evening I took a deep breath and started reading. Instantly I felt the exhilarating rush of throwing open a window to the past. Even so, my progress was slow while I got used to the handwriting. For every letter penned in an impeccable copperplate, another resembled a spidery scrawl. Sometimes the ink had faded to a ghostly sepia. Occasionally, to save the cost of a second sheet of paper, the correspondent had simply rotated the page ninety degrees and carried on writing, creating a dense lattice of words. No envelopes were used; sheets were simply folded, addressed on the front, sealed with wax and dispatched, often in evident haste.

I had observed on the family tree that my ancestors were quite unimaginative when it came to Christian names. George, John, Matthew and Richard had been standard issue for Atkinson boys since the seventeenth century. Right from the start, this small pool of names threw me into confusion, for I made the mistake of assuming that the Matthew Atkinson to whom most of the letters were addressed was my three-times great-grandfather, who had died in 1830. Only some months later did I gather that they related to another Matthew Atkinson, his first cousin, who had died in 1852; it would be several years before I discovered how these papers from a collateral branch of the family had ended up in my hands.

Matthew’s correspondence mostly concerned business local to Temple Sowerby, and offered tantalizing glimpses of various trades – banking, farming, mining – which the family had been engaged in. Until then, I had always imagined my forebears as head-in-the-clouds types, rather like my ineffectual grandfather, but these Atkinsons were worldly folk. For the first time I was able to piece together the patchy outline of a family narrative. It appeared that something had occurred during the late eighteenth century to disrupt the fortunes of the entire family. Plenty of letters touched on legal matters, with frequent references to the labyrinthine affairs of a late uncle. And then I unfolded a document that made my jaw drop – it was a ‘List of Negroes’ giving the name, age, employment and value, in pounds sterling, of each of the 196 enslaved workers on a sugar plantation in Jamaica in the year 1801.

GENEALOGY IS ADDICTIVE, and I was soon hooked. I signed up to Ancestry, the online portal to an infinitude of parish records, electoral rolls, census lists and telephone directories, all just the wave of a credit card and the click of a mouse away. I spent countless hours googling ‘atkinson’ and ‘temple sowerby’ and ‘jamaica’, and any other combination of words that might summon up evidence of my ancestors. One day I typed ‘atkinson’ into the search engine of the National Portrait Gallery website (doubtful though I was that anyone to whom I was related would have earned a place in that august institution), and a result popped up for ‘Richard Atkinson, Merchant’, whose dates matched those of someone on the family tree – my five-times great-uncle.

I clicked through to this namesake’s portrait. Instead of the conventional oil painting that I was expecting, what came up on screen was an engraving titled Westminster School, dated 4 February 1785, by James Gillray, the most savage cartoonist of his age. In the foreground, portrayed in the role of headmaster, sits the famous politician Charles James Fox, unmistakable with his bushy black eyebrows. William Pitt the Younger, the 25-year-old prime minister, is shown bent over Fox’s knee, where he is being given a sound thrashing. Meanwhile a cohort of Pitt’s ‘playmates’, held in place on the backs of prominent opposition figures, line up to await the same punishment, their buttocks bared. Poking out from the pocket of one of these miscreants is a piece of paper bearing two words, ‘Rum Contract’ – the detail which identifies him as Richard Atkinson. My head was spinning at the thought not only that a relative of mine should find himself in such rarefied company – but that our first encounter should take place at a moment when his breeches were hanging around his knees.

An internet search soon yielded a potted biography of this Richard Atkinson. He had been a West India merchant, director of the East India Company, Member of Parliament, alderman of the City of London, prominent early supporter of Pitt the Younger – and a major government contractor during the American War of Independence. His nickname, ‘Rum’ Atkinson, apparently originated from a notorious contract to supply a vast quantity of Jamaican rum to the British army headquarters at New York in 1776. He had died relatively young, in May 1785, unmarried, leaving behind an immense, self-made fortune.

BY NOW I WAS in the grip of an obsession, spending all my spare time online in pursuit of my ancestors. One evening during the autumn of 2010, I was browsing the website of Temple Sowerby House Hotel, which included a short page dedicated to the history of the place; and although it was a fairly unexciting account, one paragraph leapt out at me. This was a description of a ‘fascinating Recipe or Receipt Book’, written by Bridget Atkinson for her daughter Dorothy Clayton in 1806, which gave instructions, among other dishes, for collared eels, roasted tench and a sauce to serve with larks. I knew that this Bridget Atkinson was my four-times great-grandmother, as well as ‘Rum’ Atkinson’s sister-in-law. My sister and I had inherited a number of her books – we knew they were hers because she always signed her name on the title page – including Domestic Medicine: or, a Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases by Regimen and Simple Medicines, by William Buchan, MD; The Scots Gardiners Director, containing Instructions to those Gardiners, who make a Kitchen Garden, and the Culture of Flowers, their Business, by ‘A Gentleman, one of the Members of the Royal Society’; An Account of the Culture and Use of the Mangel Wurzel, or Root of Scarcity, translated from the French of the Abbé de Commerell; and The British Housewife: or, the Cook, Housekeeper’s and Gardiner’s Companion, by Mrs Martha Bradley. But this was the first I’d heard of Bridget having written a recipe book of her own. I publish cookbooks for a living; suffice to say my interest was piqued.

So I did something I’d never thought of doing – I stayed a night at the hotel. Arriving at Temple Sowerby around teatime, I parked near the maypole, beside the large stone from which John Wesley was said to have preached in 1782. It was a crisp November day. Across the road, the curtains of the hotel had not yet been drawn, and its brightly lit reception rooms radiated hospitality. Before checking in, I went for a short stroll, as far as the old tannery buildings at the other end of the village. Walking round the green, I found myself appraising Temple Sowerby as if visiting for the first time; with its handsome Georgian houses, coaching inn and red sandstone church, it seemed a delightful place. Much more peaceful than I remembered, too, since a new bypass had diverted all the lorries which had once rumbled through the village.

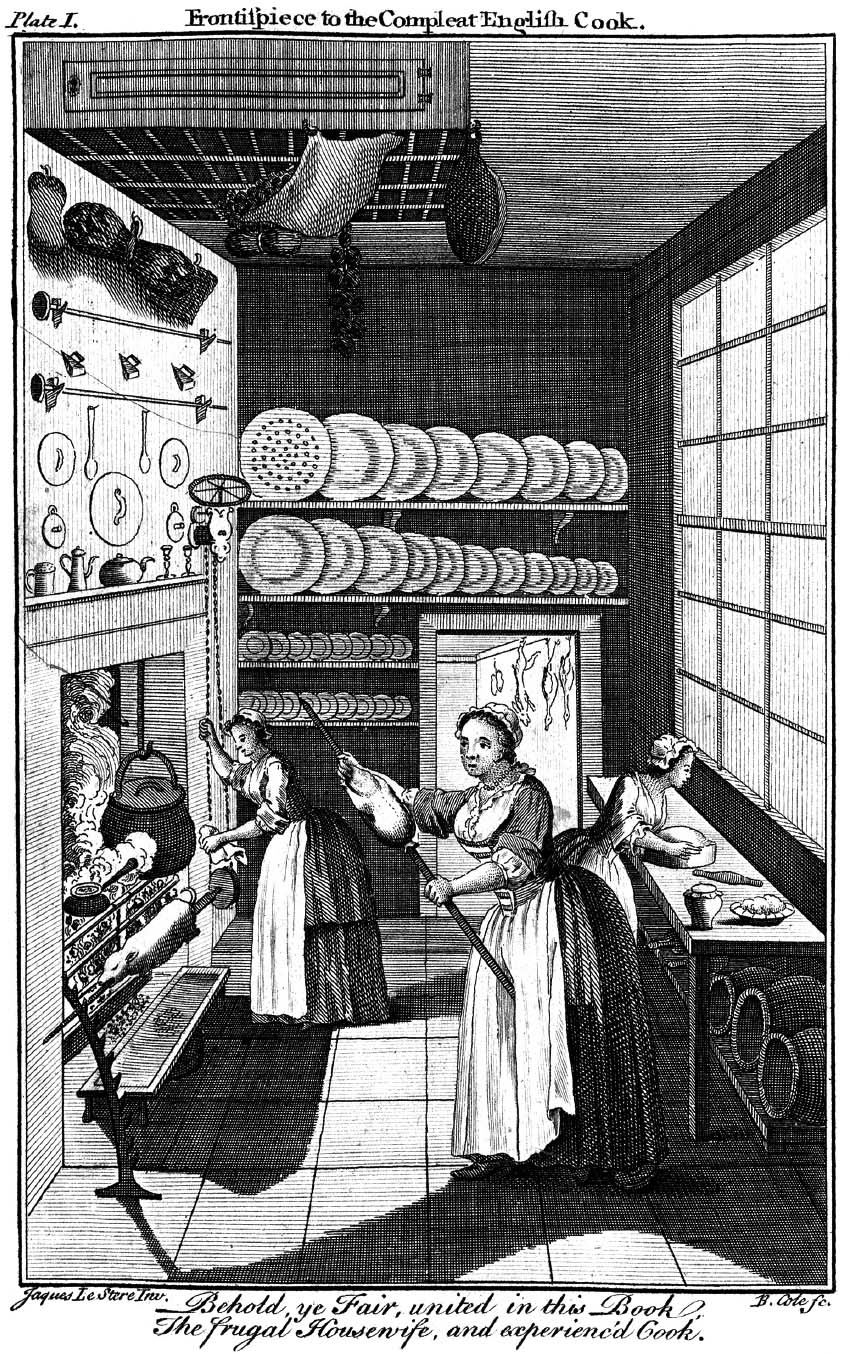

The frontispiece of Bridget’s copy of The British Housewife.

Over at the hotel, Julie Evans, one of the owners, greeted me warmly. She already knew about my connection to the house, and had reserved a room for me at the back, with a view down the garden. It was nice and cosy, in a chintzy kind of way, and the ensuite bathroom, with its Jacuzzi tub, was a definite upgrade from the spartan facilities of the Atkinson era. Even so, a small, churlish part of me resented the fitted carpets and double glazing, and yearned for the house of my grandparents. As a child, my favourite place had been the gallery, with its clattery floorboards and oak furniture, some of which now dominated my living room in south London. But it seemed that when Temple Sowerby House was turned into a hotel, in the late 1970s, the gallery had been carved up to make bedrooms, including the one I would be sleeping in. To describe my emotions as agitated would be an understatement; as I sat down to dinner, the only guest that night, I had never felt more lonely.

I had almost finished eating when Julie appeared, clutching a scrap of paper. ‘I’ve just remembered something,’ she said. ‘A few years ago, this person came to stay, and she told me her ancestors used to live here. Perhaps you should get in touch?’ She handed me the slip, on which was written an unfamiliar name – Phillipa Scott – along with a telephone number. I was intrigued.

Julie took pity on me after my solitary meal, and we chatted in the parlour. She and her husband Paul had owned the hotel for ten years, and she was clearly so fond of the place that I found myself letting go of the last of my proprietorial feelings. I’d brought a shoebox full of old family papers up from London with me, and we leafed through them together. Then I asked Julie the question I’d been burning to put to her since arriving – what could she tell me about this ‘receipt book’ that was mentioned on the hotel website? She left the room and returned a couple of minutes later, cradling an old quarter-bound book. She handed it to me; I opened it cautiously, not knowing what might be inside, and was amazed to find almost eight hundred recipes, handwritten in highly legible script.

It was evident from the sheer variety of meat, fish and game dishes in her repertoire that Bridget Atkinson had kept an excellent table. Many of her recipes included spices and flavourings that to this day carry a whiff of the exotic, such as cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, curry powder, candied lemons and orange flower water. Although the instructions she gave were cursory at best, and her methods on the antiquated side – she was, after all, cooking over an open fire – many of the recipes, especially the puddings and preserves, seemed perfectly relatable to the present. I could imagine trying to make them at home.

Not so the recipes in the last third of the book, where Bridget offered remedies for every conceivable domestic situation or ailment: ‘For Berry Bushes infested with Caterpillers’; ‘To distroy Moths’; ‘To prevent Milk from having a taste of Turneps’; ‘A Pomatum for the Face after the Small Pox’; ‘To draw away a Humor from the Eyes’; ‘For worms in Children’; ‘Against Spitting of Blood’; ‘To prevent bad effects of a Fall from a high place’; ‘To cure the Bite of a Mad Dog’; ‘For Insanity’. Some of her preparations sounded downright lethal. On a loose piece of paper tucked into the book I found ‘Mrs. Atkinson’s Receipt’, a concoction of rhubarb, laudanum and gin, all mixed into a pint of milk; it was not clear what condition it was intended for, but it seemed as though it may have been a case of kill or cure.

Bridget would have been in her seventies when she started compiling this volume for her daughter – it was odd to think she might well have written it in the same room in which I was at that moment sitting. For so long, I had associated Temple Sowerby House with death and decay; only now could I sense it as a bustling family home. In all my life, I had never coveted a single object so much as this wondrous book – so I felt crushed when Julie explained that it belonged to a private collector from Newcastle, and would soon have to be returned. I must have looked so downcast that Julie insisted I should immediately write to the owner, Miss Dunn, to ask whether I might buy the book; indeed, she thrust pen, paper and envelope at me, and promised to post my letter.

WHEN I OPENED the curtains the next morning, the sky was a brilliant blue; overnight had seen a heavy frost. After breakfast I walked across the road to the churchyard, crunching through glittery grass in search of Atkinson graves; then I set off for Northumberland, to spend a couple of nights with my godmother near Corbridge. My route over the Pennines took me on a zigzag road up the steep side of the Eden valley, through the ancient lead-mining town of Alston and across an ocean of bronze heather, dropping down alongside the South Tyne – a spectacular drive. That afternoon I had a couple of hours to spare, so I visited Chesters Fort, one of several Roman garrisons along Hadrian’s Wall, now maintained by English Heritage. I knew from my family research that some cousins, the Claytons, had once lived in the big house near the ruins, and had been responsible for their excavation – Bridget’s daughter, Dorothy, had married Nathaniel Clayton, the Newcastle lawyer who purchased the property.

Wandering around the neat stone footings, I struggled to imagine five hundred Roman cavalry ever having occupied such a peaceful spot. As drizzle hardened into rain, I took refuge in the small museum attached to the site. Near the entrance was a glass case devoted to the life of John Clayton, owner of Chesters for much of the nineteenth century. Among the objects on display was an old book which had belonged to his grandmother, Bridget Atkinson – as usual, her name was inscribed on the title page. Then something even more extraordinary caught my eye. It was the facsimile of a letter written by Bridget in January 1758, when she would have been in her mid-twenties, in which she was begging her sister to placate their mother, who was furious that she’d got married the previous Saturday without telling anyone. My heart pounded as I processed this – did it mean Bridget had eloped? And how had the museum come by this letter?

On my return to London, I wasted no time chasing up my leads – within minutes of arriving home, I had dug out the family tree and unfurled it on the kitchen table. First of all, I needed to locate Phillipa Scott, the mysterious woman whose details Julie Evans had given me. There she was, my fourth cousin – our last mutual ancestor was Bridget’s son Matthew Atkinson, the one who died in 1830. I googled her, and soon landed on the website of a needlework expert living in Appleby, six miles from Temple Sowerby – with the same distinctive spelling of her first name, this was surely the right person. It was almost midnight on a Sunday, but the urge to make contact with this complete stranger was too powerful to resist. In a short email, I explained who I was and where I’d just been. About three minutes later, Phillipa’s reply announced itself in my inbox. Hello! And, yes, she had stayed at Temple Sowerby House some years earlier, but also remembered visiting in the 1960s, as a child. ‘Is it my imagination,’ she wrote, ‘or was there a crocodile on the top landing?’

Phillipa and I spoke on the telephone the following day, and for me it was a cathartic experience. We hit it off immediately, and discovered how much we had in common; although we belonged to different branches of the tree, we shared the same deep roots. We chatted for an hour, and afterwards I felt so overwhelmed with joy that I burst into tears. A few weeks later, Phillipa put me in touch with David Atkinson, her first cousin – my fourth cousin – who invited me to stay at his house in Cheshire so that I could search through his collection of family papers. He was trusting enough to let me carry away a suitcase full of them.

I also made contact with the curator of the museum at Chesters, Georgina Plowright, who delivered a surprising piece of news. She had recently unearthed a treasure trove of correspondence between the Atkinson and Clayton families, six large boxes spanning the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in the Northumberland Archives, buried among the papers of another family, the Allgoods of Nunwick Hall. (Apparently one of Bridget Atkinson’s great-great-granddaughters, Isabella Clayton, had married an Allgood.)

And then there was Bridget’s ‘receipt book’, the scent of which had lured me north in the first place. Two days after my return, I received a call from Irene Dunn in response to the letter I had written from Temple Sowerby. She told me she was a retired librarian with a special interest in books about food; she had found Bridget’s manuscript at an antiquarian bookseller’s in Bath about fifteen years earlier. It so happened that I had approached Irene at the perfect moment. She was now looking to downsize, and was tickled by the thought of selling the book to me, a descendant of Bridget. One bright Saturday in January I travelled by train up to Newcastle to meet Irene for lunch in a restaurant on the Quayside, and to carry my prize home.

SO THIS IS THE STORY of how I found my eighteenth-century family. It was as though Bridget’s cookbook was the key I had been searching for, since doors immediately began to open. The thousands of old letters that fell into my lap as a result of my miraculous trip to Temple Sowerby – they were just the start. Within a few months I had located significant quantities of Atkinson correspondence in more than a dozen public archives and private collections on both sides of the Atlantic. My ancestors, it emerged, had occupied ringside seats at some of the most momentous episodes in British imperial history, most notably the loss of the American colonies, then the economic collapse of the West Indies. When they first sailed to Jamaica, in the 1780s, it was the most valuable possession in the empire; when they left, in the 1850s, it was a neglected backwater. Moreover, through the copious correspondence they left behind, I learnt the intimate details of their lives. Richard ‘Rum’ Atkinson, in particular, emerged as a brilliant but flawed man who amassed a fabled fortune as well as considerable power, but would have given it up in a heartbeat for the woman he loved.

It became obvious that I had stumbled upon the material for a book. Although I had edited a great many books written by other people, I had never planned to inflict one of my own on the world, being more than happy to remain on the other side of the publishing fence. But I found I couldn’t ignore this story which kept me awake at night, so I started rising at six, to spend a couple of hours writing before leaving for the office. It was hard going, and on dark winter mornings it took every ounce of willpower to drag myself out of bed. I soon discovered – perhaps surprisingly, given my professional background – that I had little idea how to go about actually writing a book. So I signed up for an evening class in ‘Writing Family History’, and it was here that I had another stroke of luck – for the teacher turned out to be the acclaimed biographer Andrea Stuart, who was then at work on Sugar in the Blood, the story of her ancestors in Barbados, black and white. One Saturday morning, she took us on a tour of the National Archives at Kew, a vast concrete behemoth where we were inducted into the practicalities of archival research; it was time well spent, for I would become a frequent visitor over the next few years. Andrea encouraged me, at a stage when I really needed it, to pursue my own embryonic Jamaican story.

I look back on this as a strange, transitional period in my life; I felt like a kind of time-travelling commuter, secretly shuttling back and forth between the present day and the world of my eighteenth-century family. It was exciting, certainly, but also emotionally challenging, as I struggled to reconcile my inborn sympathy for these people, my ancestors, with their activities in Jamaica. I was never so naive as to imagine that those activities might be unconnected with slavery, but nor was I fully prepared for the degree to which they were involved. It was not a pleasant discovery.

My eyes were opened, too, to the nature of Britain’s culpability. I learned that there were thousands of well-to-do Georgian families, like mine, whose wealth and prestige had derived from the blood, sweat and lives of enslaved Africans. Moreover, individuals from every rank of society had played their part in propping up slavery, from the royal personages who sanctioned the slave trade with West Africa in the first place, to the sailors who crewed the slave ships – even the ordinary working people who consumed the tainted sugar. Here in Britain, we have tended to keep this disturbing aspect of our national story at arm’s length; unlike the United States, where its divisive consequences are plain to see, slavery was not commonplace on these shores. We proudly celebrate our great abolitionists, of course, but we would rather not know too much about what they were campaigning to abolish.

Sometimes, after yet another grim discovery in the archives, I wondered what kind of fool would knowingly implicate his own family by writing them into this shocking chapter of history. Yet my instinct told me to press on; in fact, I felt a powerful responsibility to do so. Clearly I could make no amends for my ancestors’ misdeeds – but I could certainly attempt to make something positive out of what they had left behind. Since this mostly consisted of old letters, to tell their story made perfect sense to me. But it was essential that I should write it warts-and-all. ‘Do not try and make all the ancestors goody two shoes when some were plainly not,’ advised David Atkinson, whose messages were a tonic for my sometimes flagging spirits. ‘Detach yourself – you have every right to portray some as villains, some as “not sures”, some as feckless and some as the heroes. I suspect you might be torn on this – don’t be. You have my blessing to treat some of them hard.’

To have my newfound cousins cheering me on was just what I needed as I embarked on a long voyage into our ancestors’ past – one that took me all the way from London to the abandoned sugar plantations of Jamaica. But all roads ultimately led to Temple Sowerby, where so many Atkinsons were born and so many are buried. Their tangled inheritance may have scattered them around the world, but the evidence made its way back to that weather-beaten house in the shadow of the Pennines and, eventually, in the form of the curious miscellany of relics and papers that were my inheritance, into my hands.