THREE

![]()

Atlantic Empire

LONDON IN THE 1760s. From the ashes of the great fire a century earlier had risen a sprawling metropolis of three-quarters of a million people; the gabled timber houses which kindled the devastation had been replaced by flat-fronted terraces of fireproof brick, while stone edifices such as the Mansion House trumpeted mercantile prestige on an imperial scale. The Lord Mayor was chosen each year from among the twenty-six aldermen of the City of London, an ancient office held in 1762 by William Beckford, the inconceivably wealthy owner of three thousand slaves in Jamaica.

London was a filthy place, notable for its pall of coal smoke that smeared the sky and caught in the back of the throat. Pedestrians took care to avoid treading in the contents of chamber pots strewn across the cobbles. ‘Except in the two or three streets which have very lately been well paved,’ observed a Frenchman visiting in 1765, ‘the best hung and richest coaches are in point of ease as bad as carts; whether this be owing to the tossing occasioned at every step by the inequality of the pavement, or to the continual danger of being splashed if all the windows are not kept constantly up.’[1] The back alleys of the city clanked and clattered with the workshops of craftsmen – bootmakers, cabinet-makers, confectioners, cutlers, gunsmiths, haberdashers, hatters, mercers, milliners, perfumers, printers, saddlers, silversmiths, sword-cutters, tailors, watchmakers, wigmakers – while glass-fronted emporia lined its main thoroughfares. ‘The shops in the Strand, Fleet-street, Cheapside, &c. are the most striking objects that London can offer to the eye of a stranger,’ wrote the same Frenchman. ‘They make a most splendid show, greatly superior to any thing of the kind at Paris.’[2]

Driving London’s prosperity was trade, underpinned by the Navigation Acts. The first of these laws had been passed during the 1650s, to challenge Dutch commercial dominance, but they had since grown into the regulatory system that governed Britain’s trade with the rest of the world. The guiding purpose of the Navigation Acts was to keep the benefits of trade within the empire, and they enshrined the basic principle that raw materials produced in the colonies, such as sugar, cotton and tobacco, could only be conveyed to Britain or another of her colonies in a British ship, while all foreign-produced goods bound for America or the West Indies had to be shipped first to Britain to be taxed, then carried onwards in a British ship. It was axiomatic that the role of the colonies was to generate wealth for the mother country.

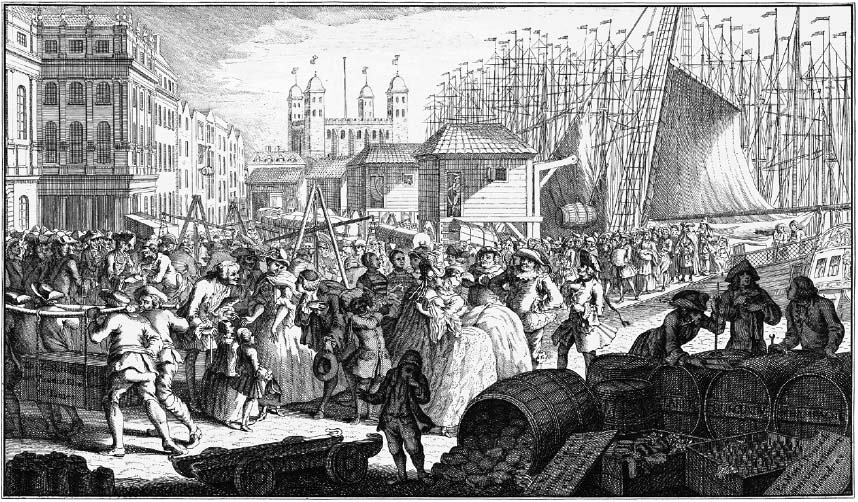

The privileged status conferred upon British shipping by the Navigation Acts gave rise to a mighty merchant fleet; and nowhere was its strength more visible than on the four-mile stretch of the River Thames from London Bridge downstream as far as Deptford. In summer months the ‘Upper Pool’ near the Tower of London resembled a dense forest of masts, and it was often remarked that you might walk from one side of the river to the other, stepping from deck to deck.

On the north bank of the Thames stood the Custom House, the portal through which so much of the nation’s taxable wealth passed in the form of sugar, coffee and indigo from the West Indies; tobacco, rice and cotton from America; timber, hemp and iron from the Baltic; and tea, silk and porcelain from China. The busiest period, from May to September, was marked by the arrival of hundreds of West Indiaman ships, heavy with muscovado sugar that would first be processed in one of the capital’s eighty refineries, then stirred into the tea on which everyone was so hooked; there was often such a backlog that a cargo might sit around for two months before clearing customs. Meanwhile, in the maze of streets behind the quays, hundreds of clerks sat hunched over ledgers in the dim light of their masters’ counting houses, totting everything up.

The crowded quays fronting the Custom House.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Which is where young Richard Atkinson, albeit tentatively, enters the frame. Even by the standards of the day, his employer Samuel Touchet was a ruthless capitalist – not that this word had yet entered the lexicon. The eldest son of Manchester’s wealthiest manufacturer of linen and cotton goods, Touchet had moved to London in the 1730s to gain better access to the market for the commodities needed by his family firm. The Touchets were early investors in Lewis Paul’s roller-spinning machine, whose operation required so little skill that anyone would be capable of spinning ‘after a few minutes’ teaching’, as the 1738 patent application boasted – ‘even children of five or six years of age’.[3] During the late 1740s, Samuel Touchet was responsible for importing more than a tenth of England’s raw cotton, and rivals suspected him of attempting to create a monopoly; by 1751, he and his three brothers together owned about twenty ships, some of which plied the infamous ‘triangular’ trade.

THE ROYAL AFRICAN COMPANY had been established under charter from Charles II in 1672, with the purpose of setting up trading posts and factories along the Gold Coast – modern-day Ghana – and exploiting the continent’s ready supply of gold and slaves. By the 1750s, Britain had eclipsed Portugal to secure dominance in the slave trade; every year during that decade, British ships carried about 25,000 enslaved Africans across the Atlantic, destined for the colonies of the West Indies and the American mainland. The ‘African trade’ was largely accepted as a necessary evil; the economist Malachy Postlethwayt declared it to be of ‘such essential and allowed Concernment to the Wealth and Naval Power of Great Britain, that it would be as impertinent to take up your Time in expatiating on that Subject as in declaiming on the common Benefits of Air and Sun-shine’.[4]

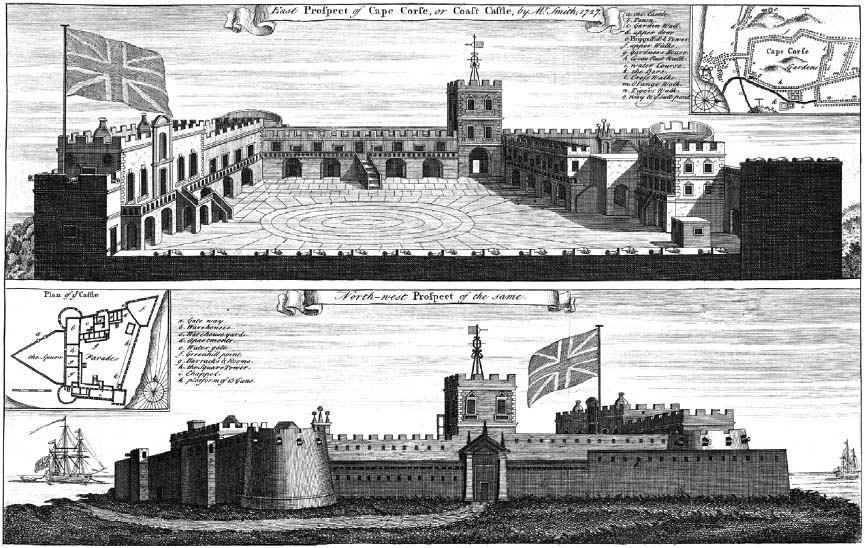

Brightly dyed, striped and checked cotton textiles, like those made by the Touchets in Manchester, were in great demand in West Africa. Indian fabrics were the benchmark against which all others were judged, but knock-off versions were fast gaining market share, and the Touchets’ were among the best. (British manufacturers continued to use the Indian names – calico and chintz would enter the English language.) As Thomas Melvil, the governor of Cape Coast Castle, the principal British slave trading post on the Gold Coast, informed the Company of Merchants Trading to Africa in August 1754: ‘If the Ashantee Paths open the Goods wanted will be Guns, Gunpowder, Pewter Basons, Brass Pans, Knives, Iron, Cowries, Silks. The Bejutapauts will go out. Of these Touchet’s are here preferred to India.’[5]

At the same time, while merchants in Liverpool, Bristol or elsewhere packed their vessels with goods to be bartered for human cargo, West African men, women and children snatched from inland villages were marched to European forts on the coast, to be sold by their captors on to a Danish, Dutch, French, Portuguese or (most likely) British slave ship. It might take a ship’s captain weeks, or even months, to purchase enough human cargo to fill its hold; two Africans per ton (bearing in mind that in shipping terms, tonnage is a measure of volume) was considered the ‘right’ load. The transatlantic leg of the voyage – known as the ‘middle passage’ – lasted around two months, and never was so much suffering crammed into so little space. Shackled and naked in the stifling heat of the ship’s belly, unable to relieve themselves except on the bare boards where they lay, rolling in blood, vomit, excrement and urine, occupying less space than a coffin, it is hardly surprising that many captives sought to end their own lives. Some tried drowning themselves, others refusing food; but it was dehydration, caused by a water ration of just one pint a day, hastened by sickness and dysentery, that would prove most deadly of all. The crew simply tossed the corpses over the side without giving them a second thought. Roughly one in ten Africans died during the middle passage.

Cape Coast Castle, the main British slave trading fort on the Gold Coast.

The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

On arrival in the Americas, the survivors were prepared for sale. Their dark skin was slathered with a mixture of gunpowder, lemon juice and palm oil, then polished with a brush, to create the illusion of glistening good health. Grey hair was either shaved off or dyed black. The backsides of those suffering from dysentery were bunged with oakum, the tarred fibre used for filling gaps between timbers in wooden ships. Human cargoes were often sold by the method known as a ‘scramble’, in which the Africans were taken to a merchant’s yard, the gates were suddenly thrown open, and the buyers rushed in, grabbing hold of their prey ‘with all the ferocity of brutes’.[6] At this point, families were often separated for ever. Afterwards, the newly purchased men, women and children were branded with the initials of their master or estate, and assigned ‘slave names’ to strip them of their previous identities; the men were often given names of generals or gods from classical antiquity, such as Apollo, Brutus, Cupid, Hannibal, Jupiter and Ulysses, as if to mock their degraded state.

Once the ship’s decks had been swabbed, then loaded up with sugar, coffee, tobacco and other commodities, it was ready to make the third side of the triangle, and return to Britain, to start this appalling cycle all over again. A triangular slave voyage typically lasted around eighteen months. The export of manufactured goods to West Africa, then the purchase of the labour with which to produce the raw materials, then the import of those raw materials from the Americas – as a business model, the diabolical logic of the triangular trade could hardly be faulted. Archive records indicate that ships owned by Samuel Touchet and his brothers took part in at least four triangular slave voyages. The first three vessels sailed to the Gold Coast between 1753 and 1757; there they embarked a total of 541 Africans, subsequently disembarking 455 in Jamaica.[7] The statistics of the Touchets’ fourth voyage mark it out as a catastrophic venture. The Favourite sailed from Liverpool in January 1760, taking on board seven hundred Africans at Malembo in what is now Angola; by the time of its arrival at the sugar island of Guadeloupe the following January, only four hundred were still alive.[8]

TRADE AND WAR have always been energetic bedfellows. During the global conflicts of the eighteenth century, ministers regularly consulted merchants for their superior knowledge of distant lands, as well as their practical experience of shipping and finance. Meanwhile, for the business community, war represented opportunity. One manifestation of this murky symbiosis between merchants and ministers was privateering, an activity considered by some to be ‘but one remove from pirates’.[9] At least two of Samuel Touchet’s vessels carried ‘letters of marque’ – the licences granted by the Admiralty to British merchant ships, permitting them to seize vessels belonging to enemy subjects. One of Touchet’s ships, the Friendship, was about to sail to the West Indies when it received its letter of marque in October 1756, shortly after the start of the Seven Years’ War; the weaponry allocated to its crew of forty men included ‘sixteen Carriage Guns, thirty six Small Arms, thirty six Cutlaus, twenty five Barrels of Powder, thirty Pounds of great shot and about fifteen hundred weight of small shot’.[10]

But Touchet had his eye on altogether greater spoils. He and a fellow merchant, Thomas Cumming, cooked up an audacious, secret scheme to invade the French colony of Senegal, fitting out and arming five ships at a personal cost of more than £10,000. Touchet’s ships sailed from separate English ports on 23 February 1758 and rendezvoused at the Canaries; from here, by previous arrangement with his friend Admiral Anson, First Lord of the Admiralty, they continued in convoy with three warships. A bar at the mouth of the Senegal River proved impassable to the naval vessels, but Touchet’s merchant flotilla landed two hundred marines and covered their march eleven miles upriver to Fort Saint-Louis. The French capitulated on 1 May. The adventurers returned laden with booty, including 400 tons of gum arabic – the sap of the acacia tree – a product essential in the printing of linens and calicoes, for which British textile manufacturers had previously been forced to pay premium rates.

So where, you might be wondering, has Richard Atkinson been all this time? There he is in the background, absorbing the rudiments of his trade; conversing with brokers and dealers at the Royal Exchange, or ’Change, the most cosmopolitan spot on earth; frequenting coffee houses, chiefly the Jamaica for West Indian business, Jonathan’s for stocks and commodities, and Lloyd’s for shipbroking and insurance; supervising the unloading of cargoes down at the quays; and generating reams of correspondence. Sadly, little evidence of Richard’s personal life has survived from his twenties. I imagine he was less raffish than his contemporary, James Boswell, who left behind a journal of his first extended stint in London that is replete with tales of encounters with writers and prostitutes – yet this is pure supposition on my part. It’s ironic and not a little frustrating that Richard, whose professional life was taken up with the meticulous recording of the smallest details, should have proved so mysterious in his private affairs – but happily, this would soon change.

Some places well known to the young Richard Atkinson.

We might infer that Richard attempted to smooth off the rough edges of his northern diction, for in May 1761 he attended a series of talks given by the Irish actor Thomas Sheridan, held at Hickford’s Concert Room on Brewer Street, on the subject of elocution. Sheridan, who was the godson of Jonathan Swift, not only advocated the ‘polite pronunciation’ of the court, but believed that regional dialects carried ‘some degree of disgrace’ about them.[11] ‘The letter R,’ he declared, ‘is very indistinctly pronounced by many; nay in several of the Northern counties of England, there are scarce any of the inhabitants, who can pronounce it at all. Yet it would be strange to suppose, that all those people, should be so unfortunately distinguished, from the rest of the natives of this island, as to be born with any peculiar defect in their organs.’[12] The price of admission – one guinea – included an ‘elegant Edition’ of the lectures in a single quarto volume, and Richard’s name is listed (as are those of ‘Mr. Francis Baring’ and ‘James Boswall, Esq’) among the book’s six hundred or so subscribers.[13]

At the general election in the spring of 1761, Samuel Touchet was elected MP for Shaftesbury. Weeks later, a financial crisis almost engulfed him. As the merchant Joseph Watkins wrote to the prime minister, the Duke of Newcastle, on 28 May 1761: ‘Private credit is at an entire stand in the City, and the great houses are tumbling down one after the other, poor Touchet stopped yesterday & God knows where this will end.’[14] Touchet’s merchant house ultimately came crashing down in October 1763, with debts of more than £300,000.

After Francis Baring’s apprenticeship expired in November 1762, he went on to set up a London office for his family firm. Business was precarious at first, and his mother Elizabeth, alarmed by his speculations, counselled him to ‘let Mr. Touchet’s example of grasping at too much and not being contented with a very handsome profit which he might have had without running such enormous risks, be a warning to you’.[15] Richard Atkinson, on the other hand, helped wind up Touchet’s affairs – a task he was said to have performed ‘with great ability’ – before taking up a position as a clerk to the West India merchant Hutchison Mure, who was based at Nicholas Lane, off Lombard Street.[16]

SAMUEL FOOTE’S COMEDY, The Patron, opened at London’s Haymarket Theatre in June 1764. It featured Sir Peter Pepperpot, a West Indian plantation owner with an ‘over-grown fortune’, drooling at the thought of a ‘glorious cargo of turtle’ and dreaming of a girl as ‘sweet as sugar-cane, strait as a bamboo, and her teeth as white as a negro’s’.[17] Such men were ripe targets for satire – although they usually had the last laugh, for their money bought them land, status and power.

Richard Atkinson’s new boss, Hutchison Mure, was one of those men who sought to convert the base metal of their West Indian fortunes into the gilded trappings of the landed aristocracy. Hailing from the younger branch of a well-connected Renfrewshire family, Mure had come to London in the 1730s. After a short spell as a cabinet-maker, he entered the West India trade, having acquired some Jamaican property through his marriage. Soon, by his mid-thirties, he had made enough money to purchase the Great Saxham estate in Suffolk. His growing portfolio of Jamaican properties, meanwhile, included one called Saxham, after his English country seat, and another called Caldwell, after the Mure ancestral home in Scotland.

It seems that Mure, who is listed in the Register of Ships for 1764 as the owner of eighteen vessels, was an enthusiastic participant in the slave trade. Between 1762 and 1766, over the course of eight voyages, 2,959 Africans embarked on the middle passage aboard his ships, and 2,527 disembarked in the West Indies, all but 521 of them landing in Jamaica.[18]

The first of these voyages was the anomaly, in that it diverted at the last moment to Cuba, which on 14 August 1762 had fallen temporarily into British hands; Mure’s ship, the Africa, landed its human cargo at Havana on 18 October. Two months later, presumably feeling flush from the profits that would follow, Mure commissioned Robert Adam to design a new house for him at Great Saxham. Adam dreamt up a vast Palladian villa with a piano nobile featuring a suite of rectangular, square, circular and octagonal state rooms – the plans are kept at Sir John Soane’s Museum, and they are magnificent. For reasons unknown, however, Mure’s palazzo never made it off the drawing board; instead he settled for the lesser option of incorporating some Adam interior designs into the old Jacobean house.

Now in his mid-fifties, Mure hoped to retire from active trade and live out the rest of his days in rusticated splendour. He was a practical man, and fascinated by agriculture; the philosopher David Hume, an old family friend, described Mure as ‘a Gentleman of a very mechanical Head’, as well as ‘one of the most judicious Farmers and Improvers’ to be found in the eastern counties.[19] And so his West India merchant house required a succession plan. Although one of Mure’s three sons, Robert, was already a partner, he lacked the flair to head such an operation; but Richard Atkinson might just be the man for the job. In 1766, aged twenty-seven, Richard became Hutchison and Robert Mure’s junior partner.

Mure, Son & Atkinson, as the new partnership would be known, began in the wake of the Seven Years’ War, when Britain was for the first time the truly dominant global power. An almost indecent number of colonial territories had been seized from France and Spain during that conflict – to the extent that Lord Bute, the prime minister, realized that concessions would be necessary to avoid a peace so humiliating to the losers that they would soon be spoiling for another fight. The question was, which of the captured colonies should Britain keep, and which ones should be given back? The debate – on which much journalistic ink was expended – focused mainly on the relative merits of Canada versus the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique.

The argument for holding on to the tiny West Indian territories and ditching Canada was obvious to most people – Guadeloupe’s exports alone were worth twenty times more than the fur trade of ‘barren’ Canada. ‘What does a few hats signify, compared with that article of luxury, sugar,’ sniffed one gentleman.[20] But the West India lobby, not enjoying the competition provided by the former French islands – the wholesale sugar price had fallen 20 per cent since their capture – pushed hard for their restoration to their previous owners. The American colonists favoured the same outcome, albeit for different reasons. Benjamin Franklin, the agent of the Pennsylvania Assembly in London, wrote:

By subduing and retaining Canada, our present possessions in America, are secured; our planters will no longer be massacred by the Indians, who depending absolutely on us for what are now become the necessaries of life to them, guns, powder, hatchets, knives, and cloathing; and having no other Europeans near, that can either supply them, or instigate them against us; there is no doubt of their being always disposed, if we treat them with common justice, to live in perpetual peace with us.[21]

In the end, the colonists prevailed. Under the Treaty of Paris, which came into effect on 10 February 1763, Guadeloupe and Martinique went back to France, while Cuba was returned to Spain; Britain held on to Canada, Florida and the sugar islands of Grenada, Saint Vincent, Dominica and Tobago.

The Seven Years’ War had started in America, escalating out of all imaginable proportions from skirmishes in the Ohio valley between colonists loyal to the British flag and an alliance of French settlers and Native American tribes. Victorious Britain now found itself mired in a national debt of historic proportions, and unable to afford adequate protection for its newly acquired American territory, as was soon proved by a series of Native American attacks on British forts and settlements to the south of the Great Lakes. As a result, in October 1763, George III issued a proclamation forbidding colonial settlement beyond a line drawn along the Appalachian watershed – much to the fury of land speculators who were intent on expropriating Indian territory.

Lord Bute resigned from the premiership after less than a year; George Grenville, who was said by the king to have the ‘mind of a clerk in a counting-house’, took over as prime minister and set about putting the nation’s finances in order.[22] It would only be fair, he argued, for American colonists to help pay for the troops needed to defend the newly enlarged empire; while each Briton contributed about twenty-six shillings to the imperial coffers every year, each American gave about a shilling.

But American colonists always made a point of challenging the mother country’s efforts to squeeze money out of them. The only revenue-raising taxes to which they would readily agree were those voted by their local assembly, while the only ‘external’ taxes remotely palatable to them were those used to regulate the trade of the British empire in its entirety, such as the import duties that fell within the Navigation Acts. Yet the Americans had signally failed to enforce the Molasses Act of 1733, which aimed through a duty of six pence per gallon to make molasses from the French West Indies prohibitively expensive, and thus tie the rum distillers of New England to the produce of the British sugar islands.

Grenville reckoned that if this duty were cut, making it cheaper to import French molasses legally than to pay the bribes and run the risks that attended smuggling, it would have the counter-intuitive effect of raising revenue; and so parliament voted to halve the tax on foreign molasses, to three pence per gallon, from April 1764. The Sugar Act sparked outrage in America. ‘There is not a man on the continent of America,’ fumed Nathaniel Weare, the comptroller of customs in Massachusetts, ‘who does not consider the Sugar Act, as far as it concerns molasses, as a sacrifice made of the northern Colonies, to the superior interest in Parliament of the West Indies.’[23] A writer in Rhode Island’s Providence Gazette ranted that American interests had been trampled by a ‘few dirty specks, the sugar islands’.[24] Their common hatred of the Sugar Act united the New England colonies for perhaps the first time, and set them on a collision course with the mother country.

BRITANNIA RULED the waves, for the time being, and her navy patrolled the waters of the North Atlantic and Caribbean, watching for French and Spanish attempts to violate her citizens’ interests. To give one trivial example, tensions had long festered over British loggers’ claims to the timber in the Spanish-held territory of Honduras. It is amid such rumblings that Richard Atkinson makes a fleeting appearance, in the earliest letter that I have found in his hand, dated 29 June 1764. He writes to the Secretary to the Treasury, Charles Jenkinson, with information from the merchant grapevine: ‘As any Intelligence concerning the Bay of Honduras will I presume be acceptable I take the Liberty to send you an Extract of a Letter from the Same Hand as the former …’[25] The letter may not make for stirring reading, but it proves that Richard was already cultivating contacts at the very highest political level.

Meanwhile, George Grenville announced a new tax on the American and West Indian colonies. A stamp duty – such as had existed in the mother country since 1694 – would be payable on a range of paper items, from almanacs, newspapers and playing cards to conveyances, diplomas, leases, licences and wills. Each colony would appoint its own stamp distributor, who would take a small cut of the proceeds, but otherwise the tax would be largely self-regulating, since without its stamp any official document would be null and void. The bill passed through the House of Commons ‘almost without debate’. Only Colonel Isaac Barré, a fearless orator whose left eye had been shot out during the capture of Quebec five years earlier, punctured the chamber’s complacency with a ‘vehement harangue’ in which he argued that the very reason the colonists had emigrated to America was to flee such measures.[26] The king gave his assent to the Stamp Act on 22 March 1765. No one could have predicted its consequences.

Resistance erupted in Boston on 14 August, when the newly appointed stamp distributor for Massachusetts was hanged in effigy from the ‘Liberty Tree’. It was unsurprising that the Bostonians should be foremost among the ‘Sons of Liberty’ – who took their name from a phrase used by Colonel Barré – since theirs was a literate and litigious mercantile community upon which the duty would weigh heavily.

By the time the Stamp Act came into force on 1 November, it was clear that the Americans’ refusal to accept the duty would have a disastrous effect on trade, since without legally stamped port clearance papers their merchant ships might be seized at any time. Relations between the American and West Indian merchant communities were already frayed; now the mainland contingent resolved to cut off trade with all those sugar islands that submitted to the Stamp Act. The Jamaicans were the most acquiescent of all – they paid more stamp duty than all the other colonies put together. One Canadian newspaper, reporting an outbreak of yellow fever in Jamaica towards the end of 1765, quipped that ‘the Inhabitants of the Town of Kingston fed so voraciously on the stamps, that not less than 300 of them alone died in the Month of November’.[27]

Although the Jamaicans certainly disliked the Stamp Act, pragmatism deterred them from rejecting it. Whereas the mainland assemblies resented being asked to pay for their own defence, the Jamaican Assembly actively volunteered a financial contribution, at the same time lobbying for an enhanced military presence on their island. The British sugar islands were surrounded by French and Spanish territories, and common sense dictated that these old enemies would soon seek to avenge their humiliation in the Seven Years’ War. Most of all, however, the planters feared attacks from within. As the ratio of blacks to whites increased on the islands – in Jamaica it was roughly ten to one – so did the danger of slave insurrections. In November 1765, as the Stamp Act started to bite, an uprising broke out in the parish of St Mary, on the north side of the island; although it was soon quashed, it must have concentrated the colonists’ minds.

Six prime ministers would hold office during the 1760s. The Marquess of Rockingham, replacing Grenville, adopted a more conciliatory tone towards the Americans – but it would be William Pitt’s denunciation of the Stamp Act which finally persuaded Rockingham that repeal was the only way out of the crisis. Over three weeks, from 28 January 1766, a committee of the whole House considered the proposed repeal bill, with a succession of merchants coming forward to describe the negative impact of the Stamp Act on both sides of the Atlantic. The star witness was the ‘celebrated electric philosopher’ Benjamin Franklin, as the minutes describe him – his experiments concerning the nature of lightning had made him one of the scientific establishment’s most venerated figures. Before 1763, Franklin testified, there had always been ‘affection’ among Americans for the mother country; but recently he had begun to be ‘Doubtfull of their Temper’.[28]

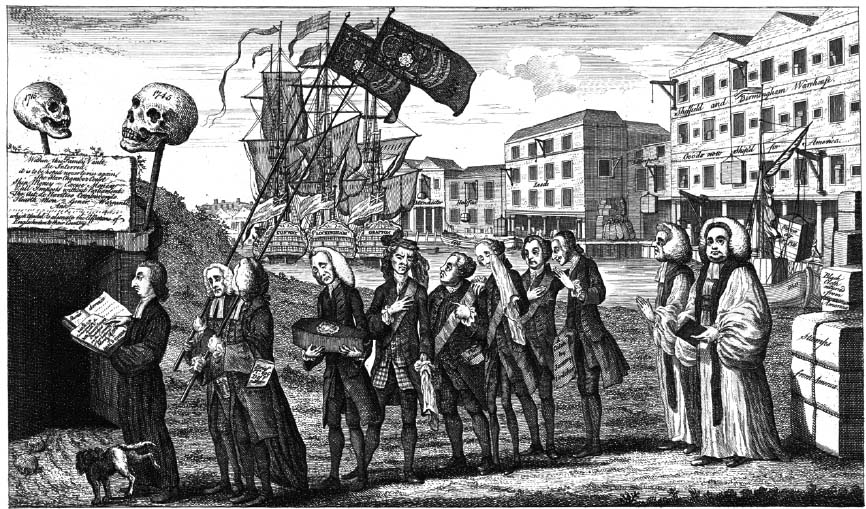

Early on the morning of 21 February, MPs started bagging seats in the House of Commons in anticipation of the afternoon’s debate. Pitt warned that parliament’s failure to repeal the Stamp Act would lead to civil war, and cause the king ‘to dip the royal ermine in the blood of his British subjects in America’.[29] For the time being, His Majesty’s robes remained snowy-white; for both houses passed the repeal bill, along with a face-saving ‘declaratory bill’ that asserted parliament’s right in principle to tax the colonies, and the king gave his assent on 18 March. American and West Indian merchant ships moored on the River Thames marked the news by hoisting their colours and blasting off their guns.

THE AMERICANS HAD MANAGED to overturn one piece of hated legislation; now they took aim at the Sugar Act. On 10 March 1766, at a gathering of colonial merchants held at the King’s Arms Tavern in Westminster, the West Indian contingent agreed that the three pence duty that Americans paid on foreign-produced molasses could drop to a single penny. This was a massive climbdown on the West Indians’ part; and yet, to their great dismay, when the American Duties Act passed into law in June 1766, it imposed a penny per gallon duty on all molasses imported into the mainland colonies, thus eliminating any advantage possessed by the British sugar islands over the French. These reforms were too technical to be of much public interest, but they marked a further cooling in relations between the colonial merchant lobbies. By now the West Indians wholly distrusted the Americans, believing them to be motivated by treacherous ambitions to trade freely with the French.

At its ‘funeral’, the Stamp Act is taken in a tiny coffin to a burial vault reserved for especially detested laws.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Until the 1760s, the West Indian interest in the City of London had been informally managed. The Society of West India Merchants emerged as a lobbying organization sometime during this decade; its precise origins are obscure, since the minutes taken at its meetings before 1769 no longer exist. Under its chairman, Beeston Long, the society usually met on the first Tuesday of the month at the London Tavern, a dining establishment on Bishopsgate Street; attendance ranged from three (a quorum) to many more when feelings about some issue were running high. As the merchants tucked into turtle flesh – these gentle beasts lived in the cellars, in tanks painted with tropical scenes to make them feel at home – they chewed over the concerns of their trade. According to parliamentary records, Richard Atkinson was among a delegation from the society summoned by Alderman William Beckford to the House of Commons in May 1766 in a last-ditch attempt to steer the arguments around the American Duties Act in the West Indians’ favour.[30] The society’s records show that during the 1770s Richard attended around six meetings every year; unfortunately the minutes are so cursory, and so devoid of descriptive colour, that it is impossible to gain much sense of his contribution.

The association between a merchant house such as Mure, Son & Atkinson, and the West Indian planters it served, rested on mutual confidence – not least because an exchange of letters between London and Jamaica often took four months or more. The merchant conveyed a planter’s sugar crop back to England and brokered its sale, taking a 2½ per cent cut of the proceeds. It also sourced and shipped out any tools, provisions and other items required for the smooth operation of the planter’s estates, subject to a mark-up; it recruited his overseers and book-keepers, and arranged their outward passage; it acted as his banker, paying bills of exchange drawn on his account, and advancing credit whenever necessary; it even oversaw the education of his children and ran his shopping errands. In short, it took care of his every need in the mother country.

But it was not quite a relationship of equals. So long as his account remained in credit, the planter maintained a degree of control; as soon as his expenses exceeded his remittances, however, the merchant gained the upper hand. The sheer precariousness of the sugar business – where hurricane, drought or rebellion could wipe out the year’s produce at a stroke – drove many proprietors deep into debt, as what started out as modest loans ballooned into unsustainable mortgages secured against their property. The merchant could foreclose whenever he chose, and many men, including Hutchison Mure, were guilty of seizing clients’ estates by this means.

John Tharp, who owned a number of estates in north-west Jamaica, retained Mure, Son & Atkinson as his London agents from 1765 to 1772. A cache of the firm’s letters sent to Tharp’s plantation house in St James Parish has survived, heavily watermarked and discoloured from years of storage in the tropics. Most of the correspondence is in Richard’s handwriting, and it is illuminating about the seasonal rhythm of the West India trade and the volatility of the sugar market. The cane crop was cut and processed during the early months of the year. Gradually, over the summer, merchant ships returning from the West Indies appeared in the Thames, weighed down with their sticky cargo; if too many ships came at once, the glut drove down the price of sugar, while a scarcity early or late in the season pushed it upwards. The letters stamped on the large hogshead barrels in which the sugar was transported identified the estate on which it had been produced; its quality could be highly variable. ‘Those of the Mark PP were much better than those of the same Mark last Year,’ Richard wrote to Tharp on 13 July 1767, ‘for these were only very brown, those of last Year were black.’[31] (‘PP’ signified Pantre Pant, a plantation that was managed by Tharp in the parish of Trelawny.)

Each autumn, Mure, Son & Atkinson sourced John Tharp’s plantation ‘necessaries’ and other domestic goods, which were shipped out to Jamaica once the hurricane season had safely passed. In December 1767, in time for Christmas, the enslaved population of Tharp’s estates were lucky enough to receive 1,107 yards of coarse Osnaburg linen and the needles with which to stitch the cloth into garments; meanwhile, for the master and his wife, there were tailored frock coats with gold buttons and braid, kid mittens, a ‘very Neat Demi peak Sadle with red morrocco Skirts and doe Skin Seat neatly stitched stirups Leathers & Girths’, a pair of brass pistols, a ‘Copper Tea Kitchin with 2 heaters’, twelve canisters of hyson tea, a ‘Gadroon’d Cruit frame’, a case of pickles containing ‘Capers Girkins Olives Mangoes Mustard Oil Soy Wallnutt French beans Colly flower Anchovies’, a hogshead of claret, casks of lavender and rose water, a selection of wallpapers, fine grey hair powder, guitar strings and the score of the Beggar’s Opera.[32]

NO CENSUS EXISTS to permit more than a guess at how many black people were living in London at this time. ‘The practice of importing Negroe servants into these kingdoms is said to be already a grievance that requires a remedy,’ reported the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1764, ‘and yet it is every day encouraged, insomuch that the number in this metropolis only, is supposed to be near 20,000.’[33] This figure seems likely to have been an overestimate, but not wildly so. Among the wealthy, black servants had cachet, while black children were often treated as toys, to be returned to the colonies once they grew up or their owners tired of them. Samuel Johnson – who was more enlightened about these matters than most – famously employed a black manservant, Francis Barber, to whom he would leave the residue of his estate.

In clarification of the Navigation Acts’ requirement that all merchandise must be transported to and from the colonies in British ships, the Solicitor General had ruled in 1677 that ‘negroes ought to be esteemed goods and commodities’ under the law.[34] But while the institution of slavery was woven into the fabric of colonial law, its status was not so certain in the mother country. According to one famous Elizabethan ruling, England was ‘too pure an Air for Slaves to breath in’, and many contradictory opinions had since been offered up.[35] In 1749, Lord Chancellor Hardwicke pronounced that a slave in England was ‘as much property as any other thing’; whereas in 1762, Lord Chancellor Henley declared that ‘as soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free’.[36] It seems baffling that such men, the greatest legal minds of their time, could be so changeable in their judgements on a question that could surely be seen as none other than the choice between right and wrong.

In September 1767, David Laird, the captain of one of Mure, Son & Atkinson’s ships, the Thames, was caught up in a dispute arising from the ambiguous status of a human ‘commodity’ destined for Jamaica. The episode had its origins two years earlier, however, when Granville Sharp, a clerk in the ordnance department based at Tower Hill, found a young black man of about sixteen injured outside the Mincing Lane premises of his brother William Sharp, a surgeon well known for treating the poor. It seemed that David Lisle, a lawyer who had brought the youth – whose name was Jonathan Strong – from Barbados, had beaten him with a pistol so repeatedly that he had almost lost his sight and could hardly walk. William Sharp had Strong admitted to St Bartholomew’s Hospital; Granville Sharp later found work for him as the delivery boy for an apothecary on Fenchurch Street.

One day during the summer of 1767, Lisle spotted Strong by accident and tricked him into entering a public house. There, backed up by two burly officials, he sold him to James Kerr, a sugar planter who was one of Mure, Son & Atkinson’s clients. Kerr insisted he would only pay the £30 purchase price once Strong was securely on board the Thames, which was then preparing to sail for Jamaica. In the meantime the young man was thrown into the Poultry Compter, one of several small prisons dotted about the City. It was from here that, on 12 September, Granville Sharp received Jonathan Strong’s letter begging for help.

Sharp called upon Sir Robert Kite, the Lord Mayor, in his capacity as London’s chief magistrate, and requested that all those with an interest in Strong should argue their claims in open court. At the hearing on 18 September, Captain Laird and James Kerr’s lawyer both insisted that the young man belonged to Kerr by virtue of a signed bill of sale. After heated debate, Kite stated that ‘the lad had not stolen any thing, and was not guilty of any offence, and was therefore at liberty to go away’. Laird immediately grabbed Strong by the arm, saying that ‘he took him as the property of Mr. Kerr’, whereupon Sharp threatened to have him arrested for assault. Laird released Strong’s arm, and all parties left the courtroom, including Strong, ‘no one daring to touch him’.[37] Kerr subsequently pursued a court action against Sharp, seeking damages for the loss of his property; he persevered with the suit through eight legal terms before it was dismissed.

The thought that right here, on the streets of London, black people could have been lawfully snatched, sold and transported against their will to the colonies, seems almost unfathomable today; but such was the reality of the Atlantic empire. This particular incident was noteworthy only in that it galvanized the man who would come to be seen as the father of the anti-slavery campaign, twenty years before Wilberforce and Clarkson took up the cause. Granville Sharp subsequently became a formidable expert in habeas corpus, and his book, A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery, would be the first major work of its kind by a British author. Which is how, in a blink-and-you-missed-it kind of way, Richard Atkinson came to be a bystander at the dawn of the abolition movement.