FIVE

![]()

All the Tea in Boston

TWICE A YEAR, great auctions of tea and other luxurious goods took place at the headquarters of the East India Company in London. The Bank of England invariably granted the Company a short-term loan before each sale, to ease its cash flow as it waited for accounts to be settled – £300,000 was the sum advanced in the spring of 1772. But with many merchants unexpectedly strapped for funds that summer and unable to pay their bills, even the almighty East India Company was snared in the financial crisis. When the Company defaulted on a payment to the Treasury in August, its wobbling finances became public knowledge and its stock price started to slide; within weeks it had tumbled from £225 to £140. The collapse, of course, came too late for Alexander Fordyce; had he been able to hold out till then, as one journalist pointed out in late September, he would have made as much money ‘as not only would have settled all his affairs, but have left an handsome fortune for life’.[1]

The East India Company’s problems stemmed partly from the American public’s widespread reluctance to consume its tea. Back in 1767, after the repeal of the Stamp Act, parliament had introduced taxes on various items – glass, paint, lead, paper and tea – imported into the colonies. While bearing a superficial resemblance to the taxes used to regulate the flow of trade throughout the British empire, the purpose of these so-called ‘Townshend duties’ (named after Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend, their originator) was to raise money for the Treasury, which made them quite as unpalatable to many colonists as the Stamp Act.

The Americans had retaliated against the duties with the powerful weapon of non-importation, which kept out around 40 per cent of British imports. Their tactic worked. In April 1770, shortly after Lord North became prime minister, all the duties were repealed, apart from the one on tea – which was kept in order to assert parliament’s authority to raise tax from the colonies. After the subsequent collapse of the non-importation movement, goods from the mother country flooded the colonies. Even so, contraband Dutch tea continued to dominate the American market; less than a quarter of the tea consumed there came through legal British channels. By the end of 1772, there were said to be seventeen million pounds of surplus leaves rotting in the East India Company’s warehouses around the City of London.

The British government had for some time wished to rein in the overbearing East India Company, and its financial woes provided Lord North with vital leverage. Through the Regulating Act, passed in June 1773, ministers gained some control over the management of India; in return, the Company was granted a loan of £1,400,000, as well as concessions to help reduce its tea mountain. Under the Tea Act, all duties previously charged on leaves imported to Britain and then re-exported to America were cancelled; the saving could be passed on to consumers. Suddenly, a pound of the Company’s fully taxed tea cost Americans a penny less than the smuggled variety. Ministers were confident that the lower prices would persuade American consumers to swallow their pride, but they were quite wrong; the colonists saw the Tea Act for what it was, a clumsy attempt to trick them into accepting the Townshend duty and thus the principle of parliamentary taxation.

On 20 August 1773, Lord North and his Treasury Board issued a licence for the export of 600,000 pounds of tea to the ports of Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Charleston. The Dartmouth, laden with 114 chests of tea, entered Boston harbour on 28 November; from then its captain had twenty days to pay the duty on his cargo, or else the vessel would be impounded. Leading merchants of the town, insisting that the tea must be rejected, requested a special clearance to allow the ship to leave port without unloading its cargo – but the governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, declined to grant permission. Soon two more vessels filled with tea arrived from London and moored alongside the Dartmouth.

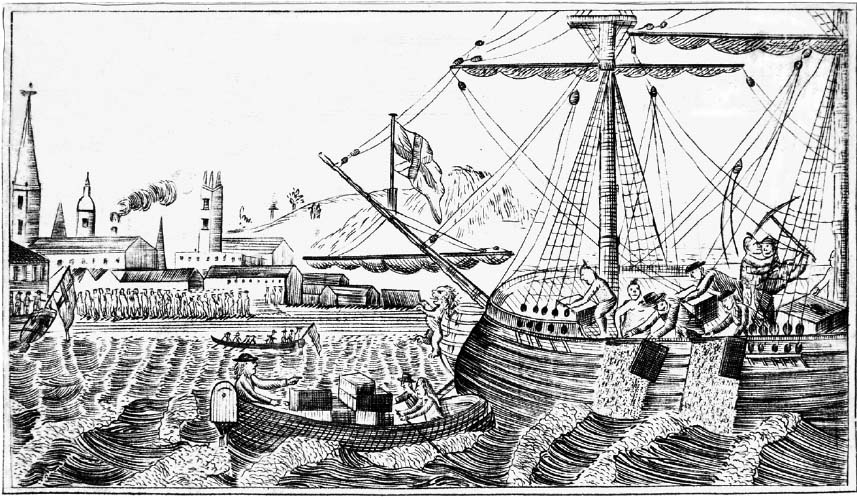

The ‘Mohawks’ empty the tea chests into Boston harbour.

Granger Collection/Bridgeman Images

On 16 December, the day before the Dartmouth’s customs payment was due, a crowd of several thousand gathered to hear the ship’s owner, a local merchant, reveal that Governor Hutchinson remained adamant in his refusal to let it depart. As the meeting broke up in the late afternoon, a number of men dressed as ‘Aboriginal Natives’, their faces blackened with coal dust, ‘gave the War-Whoop’, a pre-arranged signal to hurry to the three vessels.[2] Over several hours, by the light of lanterns, these self-styled ‘Mohawks’ smashed open 342 chests of tea and threw them overboard. Next morning, at high tide, the broken-up tea chests could be seen bobbing above a vast slick of briny sludge that stretched across the bay.

BRITISH PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS during the eighteenth century were notorious for their bribery, bullying and other skulduggery – sins which could undoubtedly be laid at the door of Sir James Lowther, who owned great tracts of Cumberland and Westmorland, and whose sense of entitlement was so inflated that he saw the parliamentary seats returned by those counties, and all the boroughs within, as his personal property.

Much more importantly – at least for the purposes of this story – John Robinson was Lowther’s law agent, land steward and chief stooge. Born in 1727 the son of an Appleby draper, Robinson had been articled to his uncle Richard Wordsworth, attorney-at-law to the Lowther family, at the age of seventeen. Over the years he had upset numerous people while executing his employer’s orders, and many blamed the ‘dirty attorney of Appleby’ for the baronet’s obnoxious behaviour in general.[3]

Lackey though he may have been, John Robinson did not lack political ambitions of his own. In January 1764, he was returned through Lowther’s influence as MP for the county of Westmorland. He would (at least in the beginning) faithfully support his patron’s interests, while forging a close friendship with another of Lowther’s men, Charles Jenkinson, the MP for Cockermouth, who was at that time Secretary to the Treasury. In 1765 Robinson acquired a long lease on the White House in Appleby, which he remodelled in Venetian style; its ogee-arched windows remain to this day an incongruously exotic feature of the town’s handsome main street.

George Atkinson was only three years younger than Robinson, and they must have moved in overlapping local circles; so it seems likely that they were already well acquainted when, in 1769, George applied to Robinson to sponsor a parliamentary bill permitting the enclosure of the common at Temple Sowerby. Indeed, Robinson may have urged George to make the application – for the enclosure of common land was a well-worn method of forging political allegiances, through the creation of freeholders who would gain the franchise. George had hitherto been ineligible to vote, for what land he owned was held under a thousand-year lease from the lord of the manor, Sir William Dalston. It certainly served Sir James Lowther’s interest to facilitate the enclosure at Temple Sowerby, for he was at the time tussling with the Duke of Portland for political supremacy in the area. Dalston, for one, detected mischief in the scheme. ‘The Lowtherians Resentment is so great,’ he told the duke, ‘as to spirit up my Lease-hold Tenants of Temple Sowerby to the Honourable House of Commons against me, for liberty to take up a large Quantity of waiste Ground where I am Lord, without consulting or acquainting me with it, and directly against my Opinion.’[4]

John Robinson’s focus shifted from Westmorland to Westminster in 1770, on his appointment as Secretary to the Treasury under Lord North. The new prime minister – whose courtesy title, as the heir to an earldom, meant that he sat in the Commons, not the Lords – was one of the warmest men in politics, with a quick wit and a nice line in self-deprecation. In his appearance, North cut a clumsy figure, of which Horace Walpole offered this uncharitable description: ‘Two large prominent eyes that rolled about to no purpose (for he was utterly short-sighted), a wide mouth, thick lips, and inflated visage, gave him the air of a blind trumpeter.’[5]

Robinson had been warned that his post at the Treasury would involve ‘a Sea of Troubles’, and it certainly required the mastery of several briefs.[6] There was the nation’s financial administration, which tied him up in correspondence with officials throughout the land; there were twice- or thrice-weekly Treasury Board meetings, chaired by Lord North, after which Robinson was responsible for issuing all the necessary orders, contracts and payments of money; and there was the role of chief whip in all but name, through which he managed the prime minister’s parliamentary business. Although the Secretary to the Treasury operated behind the scenes, he wielded great influence.

In the spring of 1773, four years after George Atkinson’s application, Robinson at last placed his private bill to enclose ‘Temple Sowerby Moor’ before parliament; royal assent was granted on 28 May.[7] Now the commissioners appointed to oversee the division of the common could get to work. The 360 acres were distributed between the heads of twenty-four households in Temple Sowerby, and the resulting fields demarcated with hawthorn saplings; the area was then mapped out on parchment and executed as a legal document. George, who bankrolled the process, was allotted fifteen acres in lieu of his expenses, taking his overall share of the land to fifty-one acres.

GEORGE III OPENED PARLIAMENT on 13 January 1774 with a ‘gracious speech’ outlining his government’s priorities for the coming session.[8] News of the Boston ‘tea party’ arrived a week later, however, and the unruly state of the American colonies suddenly trumped all other concerns. On 29 January, the cabinet agreed that strong measures would be needed to bring the colonies back into line; as a result, the passing of a series of ‘coercive’ acts would occupy parliament over the coming months.

Lord North announced the measures that would be contained within the Boston Port Act on 14 March; the town’s harbour would be shut up for business until its people had made ‘full satisfaction’ to the East India Company for the destruction of the tea.[9] The House of Commons almost unanimously welcomed the legislation; even Colonel Barré, a hero to the Sons of Liberty, gave it ‘his hearty affirmative’.[10] Three more coercive acts were nodded through before the summer recess, one of which revoked Massachusetts’ 1691 charter and restricted the people’s right of assembly; another allowed the governor to move a trial to Britain if he believed a fair hearing was unlikely in the colony; and a third permitted uninhabited houses, outhouses and barns to be requisitioned as accommodation for British soldiers. Meanwhile a law extending the boundaries of Canada, and guaranteeing the free practice of Catholicism there, angered many Americans, who saw it as an assault on their territory and their faith.

The ‘intolerable acts’, as they soon became known throughout the thirteen colonies, turned hordes of wavering loyalists against the mother country. In New Jersey, Robert Erskine continued to enjoy a frank correspondence with Richard Atkinson – ‘I write to you as a brother & as a friend, and it is a relief to give you my sentiments naked open & undisguised,’ he wrote on one occasion – but from this time onwards, his tone is one of noticeable disaffection.[11] ‘I have had a great deal too much business on my own hands to think of, much less to write on politicks till now,’ he wrote in June 1774, ‘but things draw fast to a Crisis if the news be Confirmed that an obsolete Act of Henry the VIII is to be extended to this Country whereby people obnoxious to the Governor here or Government at home may be transported for trial to Britain. I have no doubt that a total suspension of Commerse to and from Great Britain and the West Indies will Certainly take place.’[12]

THESE ILL WINDS from America did not entirely blow the domestic agenda off course during the parliamentary session of 1774. As the king had heralded back in January, his government introduced bold measures to improve the ‘state of the gold coin’, and not before time, because guinea, half-guinea and quarter-guinea coins had become so debased – through ‘clipping’ (filing metal from a coin’s circumference) and ‘sweating’ (collecting metallic dust from coins shaken in a bag) – that they were on average one-tenth lighter than their legal weight.[13] The Recoinage Act passed on 10 May 1774; by a Royal Proclamation pinned to the door of every church in the land, the order went out that all ‘light’ gold should be passed over to the official collectors for the district. They would take it at face value, cut and deface it, and transport it to the Bank of England in London, returning with pristine coin of the correct weight. Over the following four years, gold coins worth £16,500,000 would be renewed by this process.

John Robinson ran the operation out of the Treasury in Whitehall, commissioning 130 local money changers and settling terms with them. It was necessary that they should be men of substance, since the payments they would make to those handing in defective coins would need to come out of their own coffers – they would be reimbursed for their services later. ‘The Allowances are from a third to one per cent in lieu of all risque, trouble, loss of Interest and Expences,’ Robinson told prospective changers.[14] He appointed George and Matthew Atkinson to oversee the recoinage in Westmorland; the county was so remote from the capital that he allowed them a special commission of 1¼ per cent on all the money they exchanged.[15]

Robinson’s choice of the Atkinson brothers for his home county may have been rooted in old acquaintance, but they were also eminently qualified for the task, for banking had overtaken tanning to become their primary line of business. The difference between the two occupations was not so great as it might sound, for tanning was a capital-intensive trade, and large sums of money passed through the brothers’ books. Moreover, they permitted their customers what would these days be considered excessively long payment terms – often a year or more – and it was a relatively small leap from providing credit to offering bank accounts.

During the early stages of the industrial revolution, when coin was often scarce, manufacturers regularly relied on brokers to convert the bills of exchange that they received for their goods into gold and silver with which they could pay their workers. Since the 1750s, George and Matthew Atkinson had been performing this service for the proprietors of Backbarrow ironworks, at the southern tip of Lake Windermere, where it was the custom to hold a grand payday at the feast of Candlemas. Every year, in January, the partners of the ironworks would make the eighty-mile round trip to Temple Sowerby to exchange paper bills for coin; the delegation generally consisted of at least half a dozen armed men, passing as it did through some truly desolate terrain. Towards the end of 1774, however, gold was in such universally short supply – £4,500,000 had been withdrawn from public circulation over the summer – that the Atkinson brothers’ usual banking contacts in Newcastle and Glasgow could not provide the £14,000 in coin needed for the Backbarrow payday.

Over the autumn, George had conveyed several loads of ‘light’ gold – on two occasions, more than £20,000 – down to London to be recoined, and he now proposed to his friends at Backbarrow a scheme that would have to be kept secret. He wrote from Temple Sowerby:

The only method that we can think of to be on a certainty is to fetch about £8000 from London in this way – that two of your people must come here the 29th day of January with all the bills that have come to your hands then, and they shall have £4000 home with them next day. And I will go off in that night, fly to London, get there on Wednesday night, stay Thursday and Friday to get the bills discounted, and set out on Saturday or Sunday morning and be here on the 8th or 9th with as much as will make your payments easy. The only objection to this plan is the short days and dark moon, and to balance that we will take 4 days to come down instead of 3 which was our limited time last August, and after one is 60 or 80 miles from London the danger of robbery is over.[16]

Such a mission entailed a good deal of risk, for the lonely roads surrounding the capital were haunted by highwaymen legendary for their brazenness; only two months earlier the prime minister had himself been held up at gunpoint and relieved of his pocket watch and a few guineas.

LORD NORTH CALLED a general election in September 1774, six months sooner than strictly necessary, for it made sense to get this business out of the way – a ‘Continental Congress’ had recently assembled at Philadelphia to debate the colonies’ collective response to the ‘intolerable acts’, and trouble was looming. John Robinson assisted the prime minister with the purchase of seats for those men whose presence in the House of Commons the ministry deemed necessary. (With patrons of ‘pocket boroughs’ demanding around £3,000 per seat, the Treasury spent nearly £50,000.) Sir James Lowther, having quarrelled with Robinson, chose to represent Westmorland himself – George Atkinson, as a newly minted freeholder of the county, dutifully awarded Lowther his vote.[17] Robinson secured a Treasury-sponsored seat at Harwich in Essex.

Twelve of the thirteen American colonies, all apart from Georgia, sent delegates to the First Continental Congress; the sibling territories had not always agreed, but their anger towards the mother country now bound them together. ‘The Oliverian spirit in New England is effectually roused and diffuses over the whole Continent,’ Robert Erskine wrote to Richard Atkinson on 5 October. ‘The rulers at home have gone too too too far: the Boston Port Bill would have been very deficient of digestion, but Altering Charters, the due course of justice & the Canada Bill are emitents which cannot possibly be swallowed and must be thrown up again.’[18]

Congress published its resolutions on 20 October. The import of any goods from Britain, and sugar, coffee or pimento from the British West Indies, would be banned almost immediately, and no American goods would be sent to Britain or the West Indies after 10 September 1775 unless the coercive acts were repealed. On its final day, Congress issued a ‘loyal address’ to the king, listing its grievances in carefully deferential language; but since His Majesty viewed Congress as an illegal body and the imperial relationship as non-negotiable, he did not see fit to dignify the petition with a response.

The West India lobby took particular fright at the resolutions of Congress, since sugar planters looked to the American colonies for much of the basic food on which their enslaved workforce subsisted. On 18 January 1775, more than two hundred men gathered at the London Tavern to discuss what to do next; Richard was present, and he argued firmly (but with little effect) against a proposal to send parliament a petition warning of the calamity threatened by the resolutions, pointing out that since it ‘was only meant to recommend to the consideration of Parliament, what Parliament would certainly consider of themselves, it was a futile measure’.[19] His assertion would be proved correct. The government, inundated with merchants’ entreaties on the subject, set up a special panel for their assessment, which was dubbed the ‘Committee of Oblivion’. It was two months before the West Indians’ petition reached the top of the pile; by this time the ministers had already made the policy decisions that the petitioners had been hoping to influence.

It was alarming that West Indian planters should rely so much upon American grain and rice, and crucial that a substitute for these starchy crops was found – one that would grow on the islands. Thus, in March 1775, the Society of West India Merchants announced the reward of £100 for anyone who brought ‘from any part of the World, a plant of the true Bread Fruit Tree, in a thriving Vegetation, properly certified to be of the best sort of that Fruit’.[20] Captain Cook had enthused about this plant after visiting Tahiti five years earlier. ‘The fruit is about the size and shape of a child’s head,’ he had written, a rather unsettling description. ‘It must be roasted before it is eaten, being first divided into three or four parts: its taste is insipid, with a slight sweetness somewhat resembling that of the crumb of wheaten-bread mixed with a Jerusalem artichoke.’[21]

BOSTON, THE HUB OF colonial discontent, remained calm for the time being. ‘The winter has passed over without any great Bickerings between the Inhabitants of this town and His Majesty’s Troops,’ General Thomas Gage reported to Lord Dartmouth, the Colonial Secretary, on 28 March 1775.[22] Two weeks later, though, Gage received orders from Dartmouth to use force in disarming any rebels. Before dawn on 19 April, seven hundred soldiers marched from Boston to seize a stockpile of weapons from the village of Concord, some seventeen miles away. The mission was meant to be secret, but everyone living along the route had somehow been alerted. At Lexington, a skirmish blew up between redcoats and rebel militia that left eight local men dead. By the time the British reached Concord, the colonists’ stash was no longer in evidence; and as they withdrew, a running battle started that continued all the way back to Boston. Harassed by crossfire, about 250 redcoats were either killed or wounded, versus ninety rebel casualties.

These clashes signalled a new escalation of the conflict. Within days, an army of fifteen thousand rebel volunteers had mustered to block access to the peninsula on which Boston was built, and where the British were garrisoned. On 3 May, Robert Erskine informed his employers in London that he had received an application for gunpowder from the ‘principal people of the County of Borgen in the Jerseys, in which your Iron Works are situated’, and that these men were forming a militia to defend themselves against the British. He no longer believed that a reconciliation between America and the mother country was possible – unless, that is, ‘Blood seals the Contract’.[23]

Congress convened again at Philadelphia on 10 May; among the delegates was Benjamin Franklin, recently returned from London. On 14 June Congress voted to establish its own fighting force – the ‘American Continental Army’ – and appointed George Washington, a wealthy Virginia planter, as its commander-in-chief. Meanwhile at Boston, on 17 June, a British force led by General William Howe attacked the Charlestown peninsula – the closest promontory across the water from the town – and captured it from rebels occupying Bunker Hill. This was a tactical victory for the British, for it secured control of Boston harbour, but a Pyrrhic one, too, with more than a thousand redcoats dead or wounded – twice the casualties of their opponents. Only recently, ministers had sneered at the ‘raw, undisciplined, cowardly’ colonists, but General Gage advised them to think again: ‘The Tryals we have had shew that the Rebels are not the despicable Rabble too many have supposed them to be.’[24]

BY NOW, GAGE was finding it near impossible to obtain food for the eight thousand men under his command. ‘All the ports from whence our supplies usually came,’ he wrote to the Treasury on 19 May, ‘have refused suffering any provision or necessary whatever to be shipped for the king’s use.’[25] The Treasury was the Whitehall department with responsibility for army provisions; which is why Lord North, as First Lord of the Treasury (and therefore, according to convention, prime minister), needed to attend to the minutiae of feeding a garrison more than three thousand miles away. On 13 June the Treasury Board ordered their usual contractors to ship 4,000 barrels of salt pork, 6,000 barrels of flour and 1,000 firkins of butter to Boston.

News of the Battle of Bunker Hill reached London on 25 July; the following day, Lord North solemnly informed the king that the conflict had now grown ‘to such a height, that it must be treated as a foreign war’.[26] At some point it must have dawned on the prime minister and his colleagues at the Treasury that if the soldiers cooped up at Boston were to remain healthy over the winter, they would need better than salt rations to sustain them; and yet, given the onset of the hurricane season, it was perilously late in the year to start planning the dispatch of fresh food supplies. At the Treasury, it fell to John Robinson to procure the shipping that would be needed for such an operation. He soon discovered that the army’s most robust transport vessels had already left for America; meanwhile his next port of call, the London merchants who specialized in the America trade, refused to charter their ships to the Treasury, fearing the consequences for their colonial property if they were seen to be aiding the authorities. Sometime during August, it seems that Robinson sought Richard Atkinson’s advice on this knotty problem. The partnership of Mure, Son & Atkinson had never undertaken government business before, but Richard readily offered his assistance.

On 8 September, Robinson confirmed that the Treasury wished to send large quantities of food and fuel to Boston before the arrival of winter; later that day, Richard attended Lord North at Downing Street, and offered to obtain and ship the necessary items. The prime minister agreed to his terms – a commission of 2½ per cent, as was the mercantile norm – with one notable exception. Given that the price of rum was almost as volatile as the spirit itself, Lord North preferred to fix its cost beforehand; so the two men agreed to use the price quoted in the standing contract for supplying the navy with rum in Jamaica, adding on the ‘usual freight of 6 pence per gallon’, and allowances of 4 per cent for insurance and 10 per cent for leakage.[27]

The rushed manner in which Lord North engaged Richard’s services reflected the emergency. No contract was drawn up; no record of the agreement made it into the Treasury Board minutes. Richard at once committed four of Mure, Son & Atkinson’s vessels to the expedition, swaying fellow merchants to volunteer ships. These were the items on the prime minister’s ‘shopping list’:

4375 Chaldron of Coals

468,750 Galls of Porter

2,000 Sheep

2,000 Hogs

Potatoes

Carrots

Sour Crout

Onions

Sallad Seed

Malt – a small Quantity for the Hospitall

Vinegar – a reasonable Quantity for six Months Consumption

20 Boxes of Tin Plates

33,320 Pounds Wt of Candles to be shipt from Cork

100,000 Gallons of Rum – to be sent from Jamaica next Spring

400 Hogsheads of Melasses – ditto[28]

The list was largely compiled through guesswork. ‘We are busy sending out every Comfort & Conveniency for the Troops,’ Robinson wrote to Charles Jenkinson on 19 September, ‘but since Gen. Gage does not tell us anything they want or may be useful, we are obliged I may say to grope for it.’[29] The Thames set sail for Boston at the end of September, the first of thirty-six ships that would depart over the following two months as soon as their holds were packed and winds permitted. The captain of the Thames, David Laird, was not only one of Mure, Son & Atkinson’s longest-serving employees – it was he who had eight years earlier been involved in the altercation over Jonathan Strong’s fate – but was also known to General Howe, the new commander-in-chief of the British forces in America, both men having fought at the Battle of Havana back in 1762.

As is clear from his correspondence with General Howe, Richard took great pains to make sure the supplies arrived in optimum condition. Five hundred tons of potatoes were loaded gently into the ships ‘so as not to bruise them’, and onions were stored in hampers for the same reason. To guarantee the safe passage of livestock, Richard ordered generous pens to be built in the ships’ tween decks. The Lincolnshire breed of sheep was chosen as fittest to undergo the voyage, in preparation for which the animals were kept on dry food for ten days before being taken on board; the pigs were the ‘half fed kind from the Country & of a large Size, such as will pretty certainly get fat upon the Voyage, a Plentiful Stock of Beans & Water being provided for their Consumption’.[30] As a further incentive to take care of the animals, Richard offered the ships’ captains a bonus of 2s 6d for each one they landed alive.

Scurvy, which we now know to be caused by a lack of vitamin C, was by no means limited to seafaring men; it often afflicted those subsisting on salt rations. Sauerkraut, or ‘sour crout’, was widely believed to be effective against the disease, and its main ingredient, cabbage, was just then coming into season. Richard planned to send up to 300 tons of the stuff out to America. ‘We are informed that in general the Sailors have disliked it at first & afterwards grown extremely fond of it,’ he told General Howe. ‘This first dislike may we hope be lessened by our having left Juniper berries & Spices out of the composition which appear to contribute nothing to its Preservation.’ Normally, it would be unwise to seal and ship casks of sauerkraut during its six-week fermentation period, as they were likely to rupture – but such obstacles did not faze Richard. ‘We have caused Valves to be made (which cost a mere Trifle) to fix in the Bungs of the Casks which Valves being kept down by a Spiral Spring strong enough to resist any thing that can happen in rolling the Cask, will at the same time give way to a Pressure far less than sufficient to burst it & so let out the expanded air,’ he explained to Howe. ‘By this means we shall be able to ship the Sour Krout within a week or ten days of gathering the Cabbage.’[31]

John Robinson kept the king updated on the progress of the Boston expedition. ‘Mr. Robinson,’ starts one of his memoranda, ‘has the Honour to send, by Lord North’s Directions, for His Majesty’s Inspection, two Casks of Sour Crout, put up with Valves, in the same Manner as the Casks shipped for America; and also one of the Valves – The Cask marked No. 1 has been sometime made and may be nearly fit for use, that marked No. 2 is at present in a state of Strong Fermentation.’[32] No detail affecting the comfort of His Majesty’s troops was beneath royal scrutiny.

All the while, the press provided a sardonic commentary on these goings-on. ‘One person has contracted for several thousand cabbages at 3d. each, which, were they brought to market at home, would barely fetch half that price,’ reported the Evening Advertiser on 5 October. ‘It is computed, that, by the time the above sheep and hogs arrive at the places of their destination, they will stand the government (or rather the public) in no less than two shillings per pound, bones included, which occasioned a Wag to remark, that the Ministry have brought their pigs to a fine market.’[33]

DURING THE SUMMER of 1775, Congress ordered all able-bodied men to form into companies of militia – an edict that presented Robert Erskine with a headache, for he knew that were his forgemen, carpenters and blacksmiths to enlist in different units from each other, production at the ironworks would soon seize up. He therefore applied to the New Jersey Congress for permission to raise his own company of foot soldiers, and gained his captain’s commission in mid-August.

Erskine explained the situation in his next letter to Richard, neglecting to mention that the owners of the ironworks would bear the cost of the muskets, bayonets, flints, powder and shot with which their employees would, if necessary, fight the British. He also expressed his disappointment at not having received a personal letter from Richard for the best part of a year: ‘You would add greatly to my satisfaction were you to favour me oftener with a few lines directly from yourself – I know, my Dear Sir, the multiplicity of your engagements and that you have no time to throw away in letters of mere Compliments – but I cannot help wishing to hear from you were it ever so short, especially since I heard of your bad state of health.’[34] (This is the earliest mention I have found of Richard’s fragile constitution.)

It was not long before Erskine faced a crisis at the ironworks, after the London-based proprietors decided they would no longer honour his bills drawn on them. With little coin circulating in New Jersey, Erskine started dipping into his stock of iron – ‘a commodity which neither fire nor vermin can destroy’ – to settle with tradesmen.[35] As he informed Richard on 6 December:

I have between 6 & 700 Ton of pig & 20 & 30 Tons Bar at the Works and expect to make 50 more before the frost sets in. I have no reason to despair, it gives me some satisfaction to tell you so, because I have no doubt it will give you pleasure. I know it would pain you to see anyone in distress, much more one who has had so many proofs of your regard – Distress did I say? Oh my country! To what art thou Driving – this gives me poignant distress indeed. How long will madness and infatuation Continue?[36]

The first four ships of Richard’s provisioning fleet limped into Boston harbour on 19 December, with the Thames at their head, having experienced atrocious storms during the twelve-week crossing. On 31 December, General Howe wrote to John Robinson with a description of the cargoes of the nine ships so far arrived. The supplies of porter, malt, vinegar, salad seed and sauerkraut had held up well, but most of the potatoes had putrefied in the heat of the hold. Only forty out of 550 sheep and seventy-four out of 290 pigs had landed alive; their pens had proved too spacious, and they had repeatedly been ‘thrown upon one another by the Violent motion of the Ship’.[37] Most of the carcasses were too badly crushed to be fit for consumption and had been thrown overboard.

The expedition’s goal had been to bring home comforts to the besieged garrison over the winter, but it proved an abject failure. A foot of snow had fallen in Boston on Christmas Eve, and fuel was in such short supply that Howe authorized the scrapping of old wharves, houses and ships for firewood. The general would be forced to place his troops on short rations in mid-January 1776. In the end, just twenty-four of the thirty-six provisioning ships made it to Boston, including seven stragglers that arrived too late for their rotting cargoes to be unloaded, since by then the garrison was on the point of departure. (The remaining twelve ships were forced ‘by Stress of Weather’ to put into Antigua for essential repairs.)[38]

On the morning of 5 March, Howe discovered that Washington’s Continental Army had, overnight, occupied the Dorchester Heights, a lofty no-man’s-land across the water. Twenty American cannons now pointed towards Boston. The next ten days saw the packing up of the British garrison. Any ordnance that could not be carried away was destroyed or dumped in the sea; seventy-nine horses and 358 tons of hay were also left behind.[39] On 17 March, with the arrival of a fair wind, 120 ships carrying more than ten thousand troops and loyalists set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia.