NINE

![]()

Mortal Thoughts

THE RELENTLESS WORKLOAD of the war years, as well as the recent blow of his failed marriage proposal, had taken their toll on Richard’s health. He would spend much of the autumn of 1781 at Brighthelmstone, a resort in vogue ever since the publication of A Dissertation on the Use of Sea-Water in the Diseases of the Glands by Richard Russell, a local physician, nearly thirty years earlier. (The town’s altered status – from sleepy fishing village to princely destination – would be accompanied by a change of name, with ‘Brighton’ soon replacing its more cumbersome precursor.) Richard had managed to secure a good house at the bottom of West Street, overlooking the steep shingle beach. ‘The Place as full as can be conceived,’ he told Anne on 22 August. ‘All the World now resorting to the Rooms since the D & Ds of Cumberland have led the way.’[1] (The duke was a younger brother of the king, who had caused a great scandal by marrying a commoner.)

The Lindsay sisters stayed several weeks with Richard at Brighton during the season, and they made it their mission to launch him into the best society. As Anne afterwards recalled: ‘I now saw that the only way in which I could be of present use to Atkinson was by impressing on Margaret that we owed it to his friendship to give him every aid on entering more into company than his habits had hitherto led him to do.’ Music and dancing were the principal diversions at Brighton. Richard himself laid on entertainments, engaging some ‘choice Catch-singers’ from London to stay a few days of every week down in the resort; meanwhile the sisters sang at the soirées of their royal friends, the Cumberlands.[2] Anne watched Richard moving uneasily among the fashionable set, showing his discomfort in their society: ‘The manners of the excellent Atkinson were so unlike those of the day that while his heart was glowing with benevolence, ten to one his manner was astonishing all around, and creating a sensation of pain from its familiarity to the persons in the world he felt most respectfully towards.’[3]

Richard’s melancholia increased after the deaths, in quick succession, of his two eldest siblings. Jane, who had never married, died at Temple Sowerby on 26 August, aged fifty-three. Six weeks later George, suffering from a ‘large tumour on his neck’, came down to London to submit to the knife of John Hunter, the king’s surgeon; he died two days later in ‘excruciating pain’, aged fifty-one, and was buried in the little church at Rood Lane, a stone’s throw from Fenchurch Street.[4] Sadly, I have no way of finding out whether Bridget was there to hold George’s hand during his final hours, nor whether Richard was at his brother’s bedside – this event is not recorded by any family letters, only in a brief newspaper report.

Thus mortal thoughts were uppermost in Richard’s mind, and he now set about writing his will. ‘If ever Man was entitled to dispose of his fortune according to his own sentiments, it is myself,’ he would tell Anne, declaring it his intention not only to make ample provision for her in the event of his death, but also to remove any financial obstacles to her marriage to Lord Wentworth:

I am clearly convinced that the probability of enjoyment in Life is with me at an end. All my Hopes are therefore centred in standing as high as I can in your Esteem, and promoting your Happiness in the way it can be pursued; and strange as it would sound to the multitude, yet I trust my Friend will find nothing to reprove in the strong Wish I express that her Happiness were in its own way completed, and even that I could be made instrumental in accelerating it.[5]

ON 25 NOVEMBER 1781, a messenger drew up outside the house of Colonial Secretary Lord George Germain in Pall Mall, conveying a report that a Franco-American army had encircled a British force of nine thousand men at Yorktown in Virginia, and on 17 October, following ten days’ bombardment, General Cornwallis had capitulated. Germain immediately went to see Lord North at Downing Street, who received the news ‘as he would have taken a Ball in his Breast’, repeatedly exclaiming ‘Oh, God! it is all over!’ as he paced up and down the room.[6]

The Battle of Yorktown ended British hopes of holding on to the American colonies, and unleashed a tide of recriminations back home. Of all the events which had contributed to the catastrophe, a consensus formed that Sir George Rodney’s deeds on the island of Saint Eustatius had been among the most discreditable. Britain had declared war on the Dutch Republic in December 1780, infuriated by the partiality shown by this supposedly neutral nation towards its enemies. Admiral Rodney had seized the Dutch freeport of Saint Eustatius in February 1781; according to prize protocol, he was due a one-sixteenth share of all captured goods, and he chose to spend the next three months auctioning off the contents of the Dutch warehouses, rather than giving chase to his French adversary, Admiral de Grasse. In July, as the hurricane season approached, naval operations in the West Indies were suspended as usual, and Rodney decided to return to England, leaving behind a reduced fleet to follow the French towards the American mainland.

Admiral Graves had arrived at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay on 5 September, hoping to bring relief to Cornwallis’s besieged army, only to find its entrance blocked by Admiral de Grasse. The two squadrons traded fire throughout the afternoon, causing heavy damage on both sides, and Graves subsequently retreated to New York. It was the correct decision, even if it did seal the fate of the American colonies; for the destruction of the fleet would have led to the obliteration of Britain’s interests in the West Indies.

Meanwhile, in London, Sir George Rodney set about defending himself against accusations of avarice. His claims of ill health won him scant sympathy. ‘Spending so much Time in the damp Vaults of St Eustatia, in taking a minute Cognisance of their Contents, even to a single Pound of Tub Butter and Stockfish, must have affected a Constitution much more athletic than that of the gallant Admiral,’ scoffed the Public Advertiser.’[7] During the autumn, Rodney admitted a stream of visitors to his house in Hertford Street; Richard’s name appears twice in the visitors’ book, on 16 and 30 November, but we can only guess at what they discussed.[8]

Lord North’s ministry quickly unravelled following the disaster at Yorktown. The prime minister could no longer hide his ambivalent feelings about the war, long suppressed out of duty to his monarch. On 12 December, Sir James Lowther placed a motion to end the conflict before the House of Commons. North objected to the wording of Lowther’s motion, claiming that it would undermine the country’s ability to forge an advantageous peace; while Germain, as Colonial Secretary, vowed he would never sign any document recognizing America’s independence. Two days later, in a mute display of ministerial disagreement, halfway through a heated debate on the subject, North stood up from the front bench and sat down behind it, ‘leaving Lord George Germain alone in that conspicuous Situation, exposed to the Attacks of the Opposition’.[9]

The Christmas recess ought to have offered Lord North respite from his political foes; instead he found himself a hostage to his so-called friends. Henry Dundas, now Lord Advocate of Scotland, was a powerful debater who also commanded a sizeable contingent of Scottish MPs. So long as Lord George Germain continued to hold office, Dundas told the prime minister, he and his supporters would stay away from the House. At a time when the ministry’s majority was ebbing away, this ultimatum could not be ignored – and soon Germain was gone.

On 25 February 1782, Lord North announced a new loan to plug the hole in the national finances; this time £13,500,000 would be needed. To avoid a repetition of the previous year’s controversy – when Richard was alleged to have sat in a room at the Treasury where he apportioned the loan to subscribers of his choosing – the prime minister invited tenders from two groups of City men. The General Advertiser announced the winning team:

The conductors of this grand operation are no other (take them as they are) than Edward Payne, Esq., a wealthy linen-draper; the Right Honourable Thomas Harley, contractor for cloathing and remittances; the Scotch banker, Mr. Drummond, contract-copartner with Mr. Harley, and the renowned, immaculate, and undaunted Richard Atkinson, the famous rum-contractor. On the three first there needs no comment; but surely the Minister must have been drunk with contract rum, who could presume to bring the last personage forward again to public inspection … Atkinson, the former disciple, and now the fair representative of Samuel Touchet! Atkinson! of whom a late Alderman emphatically said, Samuel Touchet will never die while that fellow lives.[10]

This last was a cruel jibe – for Touchet, who was Richard’s earliest mentor, had some years before hanged himself from his bedpost, a despised and broken man.

‘We have agreed for the Loan on the same Terms we should have offered had there been no opposition,’ Richard told Anne, at the end of a long day of negotiations at Downing Street. ‘Low, but in my opinion safe.’[11] Although Mures, Atkinson & Mure this time took a £2 million share of the loan, Hutchison Mure wished to hold on to just £200,000 for the direct benefit of the partnership. Richard was free to distribute the remainder of the loan stock as he saw fit, and he chose to place much of it under his friends’ names without telling them – planning only to reveal what he had done once he could pass on ‘the gain with the intelligence’.[12] He showed this list of secret beneficiaries to Anne; her own name, naturally, came at the very top.

LORD NORTH’S MINISTRY suffered its first outright parliamentary defeat on 27 February. The following week, news came of the surrender to the Spanish of the Mediterranean island of Minorca. This event was not unexpected, for the fortress of St Philip was riddled with scurvy, and Mures, Atkinson & Mure had recently been ordered to dispatch emergency supplies of lemons, rice, molasses, essence of spruce, ‘portable soup’, salt, sugar, tea leaves and strong red wine; but still, it harked back to a dark moment in 1756 when, as Charles James Fox taunted the prime minister, the ‘loss of Minorca alone’ had been considered ‘sufficient grounds for the removal of an administration’.[13]

Shortly afterwards, what seemed like better news arrived from the West Indies – Admiral Hood had apparently trounced Admiral de Grasse’s squadron and rescued Saint Kitts from invasion. Richard obtained this information on 8 March, via a ship returning from Jamaica, and immediately passed it to Philip Stephens, the first secretary of the Admiralty. The opposition were sceptical, however, suspecting the story to be a fabrication ‘coined on purpose’ to provide relief to the failing ministry.[14] ‘That Messrs. Muir and Atkinson should fly with alacrity to Government with any thing in the shape of good news, will not be wondered at, when it is considered how deeply they are interested in it,’ commented the London Courant.[15] When official word reached the Admiralty on 12 March, it was clear that the earlier report had been an exaggeration. Hood had indeed outmanoeuvred de Grasse’s superior fleet, but still the French had managed to capture Saint Kitts.

On 15 March the ministry scraped through a motion of no confidence by just nine votes. ‘The rats were very bad,’ complained John Robinson, whose job it was as chief whip to keep the sinking ship afloat.[16] To everyone except the monarch a change of ministry seemed inevitable. For a few days the king bleakly pondered his own abdication, before reluctantly granting Lord North permission to resign.

Late on the afternoon of 20 March, Lord Surrey, from the opposition benches, stood up in the packed chamber of the House of Commons to propose a motion for the removal of the ministers; at the same time Lord North rose to make a short statement of his own. After an hour’s wrangling over which noble lord should take the floor first, North prevailed and announced the end of his ministry. Parliament adjourned immediately. Outside snow was falling, and MPs impatiently thronged Old Palace Yard while their carriages were summoned from afar. Lord North, on the other hand, had told his coachman to wait outside, so his was the first carriage to roll up. ‘Good night, Gentlemen,’ he said as he climbed in, ‘you see what it is to be in the Secret.’[17]

The following week was marked by the customary scramble to reward the loyal supporters of the outgoing ministry. One of these, James Macpherson, was a Scotsman notorious for his ‘discovery’ of an epic poem by the third-century bard Ossian, which he had ‘translated’ from the Gaelic. Published to great fanfare in 1761, Fingal had soon been exposed as a literary hoax – Samuel Johnson denounced its author as a ‘mountebank, a liar, and a fraud’. Macpherson had served the Treasury first as a pamphleteer (a role for which he was eminently qualified, given his proven ability to make things up), and latterly from the back benches of the House of Commons. Lord North wished to award Macpherson a pension, but was unable to do so unless he vacated his parliamentary seat; Richard provided a solution to this predicament, at the same time turning it to the Lindsay sisters’ advantage, by offering to pay Macpherson a lump sum of £4,200 from his own money, in return for pensions of £150 a year for each of them, to come out of a special fund set aside for ‘indigent young women of quality’.[18]

Lord North’s handwriting was dreadful at the best of times, but the letters from his final day in office betray the sheer intensity of his haste. Among the warrants sent over to St James’s Palace for royal signature on 26 March were those for the Lindsays’ pensions, and also for John Robinson’s pension of £1,000 a year. ‘In order to produce £1,000 nett, the Pension must be of £1,500,’ observed North in a scrawled postscript.[19] At nine the next morning the king wrote: ‘I can by no means think Mr. Robinson should have the fees paid out of his Pension of £1,000 per annum; I therefore return it unsigned that it may be altered, but it must be here before eleven this day and antedated some days.’[20] And two hours later: ‘Where is Robinson’s Warrant?’[21] By the afternoon, the Marquess of Rockingham had kissed hands and was again prime minister, some sixteen years since last holding the office.

Entirely unmerited though they were, no one thought to pass comment on the pensions awarded to the Lindsay sisters. John Robinson’s pension, on the other hand, generated a barrage of abuse. John Sawbridge, an MP for the City of London with a republican reputation, launched a vindictive attack on Robinson in the Commons. Why did Robinson need this lavish sum, when he already owned a ‘very fine house’ in St James’s Square and a ‘most superb villa’ just outside the metropolis? And how had he been able to buy these valuable properties in the first place? In response, Robinson disclosed that he had sold his ‘paternal estate’ in Westmorland for £23,000, and had given the proceeds to his daughter on her recent marriage; that he had borrowed £12,800 to buy his ‘small house in the country’; that he did not own the house in St James’s Square, but had taken it on a repairing lease for the annual rent of £150; and that he had a backlog of bills and two families to support.[22]

Sawbridge’s insinuation was that Robinson had derived financial benefit from his connection to his favourite contractor – but whether Richard ever paid backhanders to the Secretary to the Treasury, we’ll never know. Certainly, though, Richard had recently assisted his friend with a delicate money problem. In August 1781, Robinson’s only child Mary had become engaged to Henry Nevill, the heir to Lord Abergavenny. Much to the future father-in-law’s disappointment, however, the young blood had turned out to be a gamester. Robinson, having already settled a dowry of £25,000 on his daughter, agreed to bail Nevill out, but insisted on a full reckoning of his debts. Richard had gone down with Robinson to Sussex, and then to Monmouthshire, to perform the due diligence that preceded the marriage. When Nevill, having sworn he owed no more than £18,000, discovered the true figure to be £26,000, he persuaded his attorney to present a false account to Robinson, and agreed to repay the secret balance from his wife-to-be’s marriage settlement. After the wedding, Robinson cleared all the debts admitted by Nevill, and Richard paid off tradesmen’s bills worth more than £400. All this expense would almost ruin Robinson; he gave up the house in St James’s Square, and sold his coach-horses. Unsurprisingly, he chose not to divulge these details in the House of Commons.

WHILE LORD NORTH’S ministry was fading away, France plotted its annexation of Britain’s sugar islands. Faced with such a clear danger, the West India lobby put aside their political differences and on 2 January 1782 presented a grand petition to George III in which they begged for ‘reinforcements, naval and military’ to be sent without delay. The king, it was reported, received the petition with a respect that had not always been ‘shewn to his people’ when they had ‘presumed to approach him on the subject of public grievances’.[23] Unusually for a document that implied criticism of the ministry, Richard was one of the signatories.

Violent winds in the English Channel prevented Admiral Rodney’s fleet from setting out for the West Indies until mid-January 1782. All this time, the French navy under Admiral de Grasse continued to pick off the Leeward Islands; the fall of Saint Kitts was swiftly followed by the surrender of Nevis and Montserrat. On 25 February, Rodney finally joined up with Admiral Hood, and the combined fleet anchored at Saint Lucia, where it was well positioned to keep watch over the enemy at neighbouring Martinique. By 8 April the French were on the move, and believed to be planning a rendezvous with the Spanish at Santo Domingo before heading west to Jamaica; the French flagship, the Ville de Paris, was rumoured to have fifty thousand manacles on board, to be used for restraining the island’s enslaved population.

Early on 12 April, the British caught up with the French off the coast of Dominica, near the rocky islets known as Les Saintes. The engagement started in the time-honoured manner, with the warships of the two nations – thirty-six British, thirty French – sailing in parallel lines in opposite directions while blasting away at each other. But after several hours’ battle, when the smoke was at its thickest, the wind changed, which suddenly divided the French line. A number of British vessels were able to glide through the gap, and proceeded to bombard the enemy at close range from both sides. By evening, five French ships had been captured, including the Ville de Paris, with Admiral de Grasse on board. The fatalities ran into thousands; the sharks fed well that night.

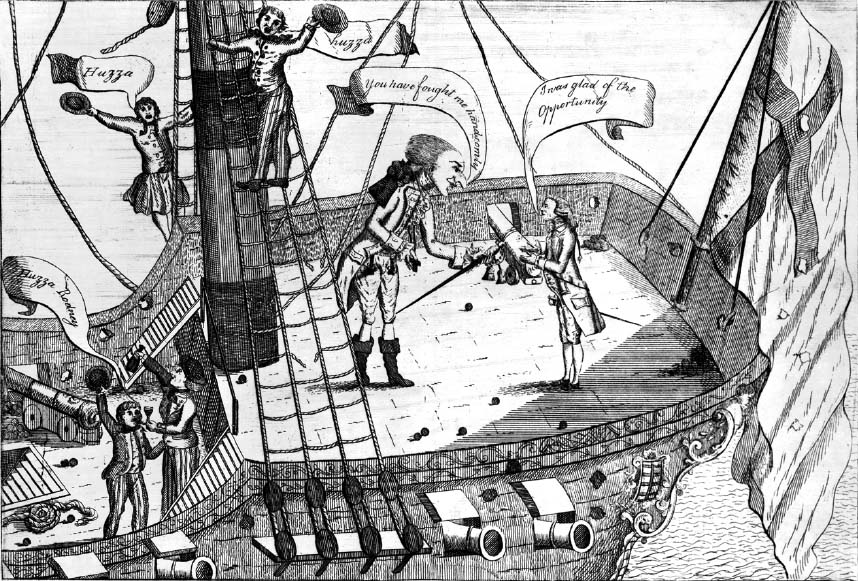

Admiral de Grasse relinquishes his sword to ‘the Gallant Admiral Rodney’.

Bridgeman Images

The story of this great British victory, by which Jamaica was rescued from the clutches of the French, electrified the nation. The Battle of the Saintes was the first time that ‘breaking the line’ was recognized as a naval tactic, and in its aftermath the theoreticians squabbled over whose idea it had been. It’s possible that Richard played a small role in its conception.

John Clerk of Eldin, the Scottish author of an influential textbook about naval tactics despite never having been to sea, was the first to take credit; he claimed to have attended a meeting with ‘Richard Atkinson, the particular friend of Sir George Rodney’ in January 1780, at which he had communicated his ‘theories of attack from both the windward and leeward’, in particular his ‘doctrine of cutting the enemy’s line’, all of which Richard had promised to tell the admiral.[24] The playwright Richard Cumberland, on the other hand, believed the idea had occurred to Rodney while they were both the guests of Lord George Germain during the autumn of 1781; Cumberland recalled the admiral rounding up a heap of cherry stones at the dinner table and arranging them ‘as two fleets drawn up in line and opposed to each other’, before animatedly steering the pips representing his warships among those of his enemy.[25] Both accounts were later disputed by Sir Howard Douglas, who insisted that his father, Rodney’s Captain of the Fleet, had been the ‘original suggester’ of the manoeuvre.[26] In any case, through his brilliant deployment of this tactic at the Battle of the Saintes, Admiral Rodney was reinvented as the great saviour of the empire, a silhouette to be found gracing countless commemorative medals, tankards and punchbowls.

DESPITE HIS FAILURE to unite the Atkinson and Lindsay lines through marriage, Richard continued to promote the interests of both families. Through the patronage of Sir William James, one of his partners in the contract to provision the army in Canada and chairman of the East India Company in 1779, Richard had obtained a coveted Bengal writership – a junior clerical position – for his nephew Michael Atkinson, George and Bridget’s eldest son.[27] Richard’s next nephew, George, had meanwhile joined Mures, Atkinson & Mure’s counting house at Fenchurch Street in order to learn the rudiments of the West India trade, with a view to joining the partnership at some future date.

As for the Lindsay family – Richard’s devotion to their cause was almost limitless. Anne was by now the mistress of a £30,000 fortune after he managed to sell her ‘secret share’ of the 1782 loan for a ‘princely gain’.[28] Richard also loyally served the interests of Anne’s brothers, in particular guiding the older ones through the complex negotiations for army commissions – the going rate for a lieutenant-colonelcy being at that time around £5,000. Alexander, sixth Earl of Balcarres, who was Anne’s junior by thirteen months, had served under General Burgoyne in America, proving his mettle (and good fortune) during fierce fighting near Ticonderoga, where ‘thirteen balls passed through a jacket, waistcoat, and breeches’ without inflicting so much as a scratch.[29] Soon afterwards, at Saratoga, Balcarres had been captured and paroled to New York in exchange for a Continental Army officer of the same rank.

Colin Lindsay, Anne’s third brother, had also served in America before landing at Gibraltar with Rodney’s expedition in the spring of 1780. Two years later he was still cooped up there, and the garrison’s supplies were once again running low. So impregnable was the Rock that the French and Spanish allies could find no way of taking it by land; instead they planned a grand assault from the sea. A French engineer devised a system of floating batteries, built from the hulls of old vessels; ten of these monsters, each armed with fifteen cannons, were anchored in a line five hundred yards from the shore. The offensive started on the morning of 13 September 1782, and the batteries went to work blasting away at the fortress.

But one commodity of which Gibraltar did have plenty was coal, left over from Richard’s supply eighteen months earlier. By late afternoon the garrison’s forges had built up a blistering heat, and it was time to unleash the British secret weapon – more than a hundred cannons which rained down red-hot shot on the floating batteries. Within hours they were destroyed, and nine enemy warships had also been consumed by fire. The following month, Admiral Howe sailed unchallenged into the bay with thirty-four warships and thirty-one transport ships, bringing relief to Gibraltar for the third and final time. Richard played no role in this mission; for the new Treasury Board showed no desire to engage his services.

THE YOUNGEST OF the Lindsay sisters, nineteen-year-old Elizabeth, married Philip Yorke, heir to the Earl of Hardwicke, in July 1782; Richard helped draw up her marriage settlement.[30] Announcing the nuptials in its gossip column, the Morning Herald also suggested that another marriage was imminent, though ‘not with quite so much advanced certainty’, between Lady Anne Lindsay and Viscount Wentworth.[31] But this was no longer true; for the death of Catharine Vanloo several months earlier had dealt their engagement a fatal blow. Anne now felt that were she to marry Wentworth, it would be merely to fill the vacancy left by his late mistress.

Nor had he curbed his gambling. Late one evening that summer, Wentworth turned up at Harley Street in great distress and confessed to Anne that he had spent the previous three days and nights at his club, where he had squandered such a vast sum that he had been forced to borrow from moneylenders on terms ‘usurious beyond the common pitch of usury’. Anne’s decision to free him from the grip of these men derived more from pity than love; and he could never know that it was she who had saved him. With some reluctance, for it would not be easy to explain her motives ‘without opening ill-healed wounds’, she asked Richard to carry out the business on her behalf.[32] Wentworth accepted Richard’s offer of a loan with complacent civility, and unwittingly borrowed £4,500 of Anne’s fortune. ‘I have been very busyly employed in paying money lately, & this morning have washed my hands of all Israelitish connections,’ he told his sister on 20 August. ‘I am now as poor as a Rat, tho’ hope I have laid in a fresh stock of credit, which I shall use sparingly.’[33]

A few months later, Richard rescued Anne from another unpleasant situation. ‘Leon’, a blackmailer who appeared to have inside knowledge of Wentworth’s rackety private life, perhaps through a connection with the late Mrs Vanloo, threatened to publish all the love letters Anne had ever written to him, and thus reveal to the world the ‘Villanous art’ that she had practised against his dead mistress: ‘how you endeavourd by every means in your power to push her away from his house from his Children to send her abroad – in short what did you not do to make her miserable that you might triumph as Lady W – a title his Lordship never meant to bestow upon you’.[34] Richard drafted a sharp reply, which was duly left at Seagoes Coffee House in Holborn. ‘Your threatening Letter has been laid before Counsel,’ he wrote, ‘and it appears that by Act of Parliament the punishment for sending it is Death. From circumstances known to one of the Persons mentioned you are already in part traced, and to push the Enquiry to your compleat Detection and punishment is far from difficult. The smallest publick Impertinence will at once fix that purpose and facilitate its execution.’[35]

Although Richard always insisted that Anne’s fortune was hers to treat entirely as she pleased, and pressed her to spend more, she had mixed feelings about doing so. She appreciated the luxuries it bought, such as the well-appointed box at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket, within nodding distance of the Duke of Cumberland and Prince of Wales’s boxes – her subscription was in Richard’s name, but she had all the benefit.[36] She did not, however, enjoy the secrecy surrounding her money; and nor could she shake the feeling that it was slightly ill-gotten. ‘I often wished,’ she later wrote, ‘I could have possessed my pension and a quiet £5,000 only, rather than be subjected to the censure of people who might blame me for deriving any advantage from the Funds, thro’ the means of a rejected lover.’[37]

For various reasons, Richard was short of ready money during the latter months of 1782, and Anne was happy to tie up half of her capital, some £15,000, to relieve him of the burden of a loan to the estate of the late Captain John Bentinck. But when Richard tried to persuade her to accept documents that would identify her as a mortgagee on the Bentinck estate in Norfolk, she refused, feebly protesting that she did not have a writing desk to lock them in. When he offered to buy her such an item, a fear that he would make an expensive present of it tyrannized over her better judgement. ‘I promised I would procure myself a bureau,’ she recalled, ‘but without intending to do it.’[38]

The will that Richard began planning in the wake of his siblings’ deaths had meanwhile swollen into an ambitious document; it had taken him and his lawyers more than a year to prepare. On 22 December 1782, the day before he signed it, Richard sent the final draft over to Anne, along with a covering letter, to make sure he had her concurrence ‘in the propriety’ of every part of it:

I cannot say that I am sorry to find a necessity for changing the Plan we before talked of and tying up the Estates for the present Generation. I think it will be the means of their doing the more good. I have no Wish that any Nephew of mine should be put above being the Builder of his own fortunes, for I do not think it would contribute to his happiness. Assistance therein I would afford him, but not enough to make him dream that he was to plant himself there, and live a vegetable Life upon the Income. As the matter now stands arranged, I solemnly declare I think I have left as much to my own family as will do them any good, and that my own Sentiments are somewhat wounded by leaving so little in your power, and I sincerely ask it of your friendship to tell me truly your thoughts thereon.

At this point, Richard enters into a rather tortuous declaration of the ‘ardor’ with which his soul rushes ‘to a communication’ with hers ‘in points where I feel they are made to embrace each other in spite of all the empty formalities of Life’ – before acknowledging that he is ‘wandering’ from his purpose, and continuing:

Let us my dear Friend talk all this fully over & put it into such form as may be most to the purpose if the Event of my Death should happen – and forgive this ill connected Letter – when I took the Pen I meant only to write half a dozen Lines … but I am some way got into a way of writing straight forward to you, without forethought or attempt at Correction of what I have wrote, that indeed is not a careless contempt of my Friend – but (as I think) a part of that extreme desire which possesses me to throw my whole Heart open to her, to throw its most secret Sensations unveiled before her. The Consciousness that her Eye must review it would be sufficient to keep out all the black Family, & as to human Frailties, the Heart knows much less than mine that does not know that under the Influence of a generous confidence they would become the very Cement of its best Happiness. But there’s no end of Dissertation. And so – it being near two in the morning, I say – Fingers be at rest – & Mind take thy chance of being so to.[39]