TEN

![]()

A Royal Coup

SHELVES EITHER SIDE of my sitting room fireplace display blue and white Chinese porcelain of a pattern representing flowers and butterflies – plates, bowls, sauceboats and soup tureens – the remnants of a much larger dinner set which evidently saw plenty of active service in its day. I had always wondered how this china might have come into my family, but it was only when I found out about Richard Atkinson’s ship, the Bessborough, that its provenance began to emerge.

Launched at Rotherhithe on 27 November 1772, the Bessborough held one of the East India Company’s valuable licences to carry porcelain, silk and tea back from China. Such ships were the supertankers of their day – the Bessborough was 144 feet long and 39 feet broad, with three decks and 907 tons’ capacity. Richard commissioned the building of the vessel and acted as its managing owner, a role known as ‘ship’s husband’. Shipping on such a scale and over such epic distances carried grave risks, too great for an individual to bear, and East Indiaman vessels were typically owned by syndicates, their holdings divided up into one-sixteenth shares.

When the Bessborough returned from its second voyage, in October 1781, it was in need of a total overhaul. (It had been caught up in conflict on the Indian subcontinent during the four years it was away, having assisted in the blockade of the French enclave of Pondicherry in August 1778.)[1] Some prickly correspondence about the repairs reveals tensions between Richard and another of the Bessborough’s owners, the globetrotting botanist Sir Joseph Banks. On one occasion, when Banks sent a note complaining how long it was taking to put the ship into dry dock at Deptford, Richard’s reply conveyed a clear flash of irritation. ‘I very frankly confess to you,’ he shot back, ‘that I think the Distrust expressed by your Letter of this Date might have been spared till you had better foundation for it than the Suggestions to which you seem lately to have paid attention. I know of no reason but the want of Water for the Bessborough’s not getting into Dock, and believe that no other exists.’[2] By December 1782, the newly copper-bottomed Bessborough was once again seaworthy and ready to embark upon its third voyage to China.

One afternoon at the British Library I was scrutinizing a hefty tome called Chinese Armorial Porcelain, hunting through thousands of pictures for a match with my own china. I turned a page, and there it was – a plate exactly like mine, apart from the coat of arms painted in its middle. (The Atkinson version has a humble monogram.) ‘Montgomerie quartering Eglinton,’ read the caption. ‘This service was undoubtedly made for Captain Alexander Montgomerie of the Hon. East India Company who commanded the East Indiaman Bessborough at Canton in 1780.’[3] It was a eureka moment – I could only imagine that Montgomerie must have purchased my porcelain at the same time as his own.

This explanation, already plausible, was later reinforced when I found Captain Montgomerie’s papers relating to the Bessborough’s second voyage in the library of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich. The East India Company allowed its ships’ officers generous personal trading allowances – eighty tons going out, sixty tons coming home – and the first of Montgomerie’s invoice books records that his outward cargo included beads, buttons, gold thread, ribbons, canvas, cordage, saddlery, claret, port, Jamaica rum, glassware, hats, linseed oil, tar, ironware, sheet copper, knives, sword blades, pianofortes, sheet music, stationery, prints, periodicals and books. It also shows that he bought 262 chests of opium in India, to be exchanged for tea in China.[4] A second invoice book records that on the return passage, Montgomerie’s personal goods included hyson tea, cassia bark, rhubarb, wallpaper, silks, nankeen (a kind of cotton cloth), ‘Gambouge’ (a deep yellow pigment) and porcelain. More specifically, listed among his buys at Canton in November 1780, from a merchant called Synchong, are ‘3 Table Setts of the Best Blue & White Stone China, scolloped border, Gold Edge, & Landscape pattern consisting of 170 Pieces’, as well as another set of the same pattern bearing ‘Captn. Montgomerie’s Arms’.[5] This, I am certain, is the record of my china’s purchase.

A soup tureen, brought back from China on board the Bessborough.

Andrew Davidson

THE HEADQUARTERS OF the Honourable East India Company – to use the official title of this most morally dubious of corporations – were on Leadenhall Street, two minutes’ walk from Richard’s premises in Fenchurch Street. Behind a deceptively narrow façade, East India House stretched back some three hundred feet, and included rooms for the twenty-four directors and their clerks, a garden and courtyard, warehouses, and a General Court Room for the meetings of stockholders, known as ‘proprietors’. The East India Company’s politics had grown ever more rancorous over the previous decade, despite the supposed restraining influence of Lord North’s Regulating Act of 1773. This legislation had subsumed the presidencies of Madras and Bombay under Bengal’s control; but Warren Hastings, promoted to Governor General of Bengal, had proved a divisive figure, and Lord North’s attempts to dismiss him had been thwarted by the proprietors. Meanwhile, John Robinson had set about building a government power base within the Company by actively encouraging the ministry’s supporters to purchase stock, holding out the possibility of rewards for those who made themselves useful in the General Court of Proprietors. Richard had owned stock nominally worth £1,000, enough to qualify him to vote, since October 1773.[6]

It was inevitable, given the extent of his commercial interests, that Richard should cross paths with some shady characters, and the aforementioned Paul Benfield, co-purchaser of the Bogue estate in Jamaica, was perhaps the shadiest of the lot. How Richard first got mixed up in his affairs is not entirely clear, but the two men likely met in late 1779 or early 1780; it would be an exaggeration to call them friends, but they must have seemed useful to one another. Benfield – nicknamed ‘Count Rupee’ – was a key player in one of the East India Company’s most toxic scandals, which had originated in Madras during the 1760s. The business centred on the spiralling debts of the Nawab of Arcot, ruler of southern India’s Carnatic region, who had borrowed vast sums at exorbitant rates of interest from many local Company officials.

Benfield, who was foremost of the old man’s creditors, was among a handful of Company servants recalled to England to account for their disruptive activities. John Macpherson was another; he arrived in London in July 1777, joining forces with his cousin, James ‘Ossian’ Macpherson, on a press campaign to justify his actions. (It was James Macpherson whose pro-ministry pamphleteering would later be rewarded with a lump sum paid by Richard on Lord North’s behalf.) Benfield purchased a Wiltshire estate that included an electoral interest in Cricklade, a borough with notoriously bribable voters; at the general election of September 1780, he and John Macpherson were returned as the town’s two MPs. Three months later, the directors of the East India Company cleared Benfield of wrongdoing and granted him leave to return to Madras. However, a group of irate proprietors led by Edmund Burke pressed for a hearing of their own. At the subsequent inquiry, on 17 January 1781, the motion was carried in Benfield’s favour by a narrow margin; a week later he set off for India.

It was in the midst of all this clamour, on 31 December 1780, that Richard and Benfield had each signed the legal instrument with which Hutchison Mure vested in them the joint ownership of the Bogue estate.[7] Benfield had no wish to become a sugar baron; his share of the investment was simply a vehicle for his East Indian loot. He would gradually pay for his half of the Jamaican property with bills, gold and diamonds remitted from Madras.

In March 1781, eighteen-year-old Michael Atkinson – George and Bridget’s eldest son – sailed to Calcutta to take up his East India Company writership, travelling on the same ship as John Macpherson, recently appointed by Lord North to the Supreme Council of Bengal. Michael’s family connections would prove of great value on the subcontinent. ‘Our friend, Mr. John Macpherson, will explain to you how much we all owe in these disagreeable times to the ability, friendship and exertions of Mr. Atkinson,’ James Macpherson wrote to Governor General Hastings on 22 April 1782. ‘Mr. Atkinson has a nephew, under your government, who went out last year under the protection of Mr. Macpherson. In policy, as well as gratitude, decided support and a marked attention are due to that young gentleman on account of his Uncle.’[8]

TIME AND AGAIN I would marvel at Richard’s uncanny knack of positioning himself, if not at the epicentre of major events, then extraordinarily close by. Often it feels as though he is just offstage, pulling strings – something that James Gillray suggests in an early engraving, Banco to the Knave, which was published on 12 April 1782, just after the fall of the North ministry. Lord North is depicted presiding over a large card table, looking down dolefully as he acknowledges that it is all over; Charles James Fox has a huge pile of gold guineas in front of him, Lord Rockingham a smaller one. A cheering crowd of supporters throngs round them; and at one end of the table sits a croupier, representing (though looking nothing like) John Robinson, who says simply: ‘Atkinson cut the cards.’ Richard’s political skills would come into their own during the two years of intense turbulence that followed the demise of Lord North’s government.

Banco to the Knave, in which the change of ministry is likened to a game of cards.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Lord Rockingham’s ministry was short-lived, for he died from influenza in July 1782. The most pressing business of his successor, the Earl of Shelburne, was to end the war; the provisional terms of an Anglo-American peace treaty were signed in Paris on 30 November. The new land boundaries between the British territory of Canada and the fledgling United States of America were drawn on terms that were noticeably generous to the latter. ‘The English buy peace rather than make it,’ the French foreign minister sniped from the sidelines.[9]

Many MPs agreed with this assessment – the prime minister had given too much away. John Robinson was troubled to learn that Lord North was planning to vote against Shelburne’s peace treaty, and drafted a memorandum to his old master, warning that such an action might ‘shake the Government and the Constitution of this Country to its Foundation’.[10] He asked Richard for his thoughts on the document. ‘Upon the best consideration I can give the matter, I cannot help feeling an Indelicacy towards an old Friend, in the communication,’ Richard replied on 6 February 1783.[11]

As Shelburne’s grip on power weakened, it was clear that he would need to join forces with one of the other main parliamentary factions, but he failed to form a coalition with either Lord North or Charles James Fox. Instead something unthinkable happened. Fox sent a ‘civil’ message to North, and these once-mortal enemies met to coordinate tactics for a forthcoming debate. Only recently, Fox had declared that he would not ‘for an instant’ consider working with Lord North or his allies – men who ‘in every public and private transaction’ had shown themselves ‘void of every principle of honour’.[12] Now MPs were flabbergasted by the spectacle of Fox and North sitting side-by-side on the opposition front bench. On 24 February, the weight of adverse parliamentary numbers bearing down upon him, Lord Shelburne tendered his resignation.

At this time, broadly speaking, there were two political parties – Whig and Tory – but they were not monoliths in the sense that we know today, instead loose social alliances sharing a general outlook, clustered around strong individuals. Aristocratic Whigs had engineered the Glorious Revolution, and they saw political power as emanating from the people through a ‘contract’ existing with their monarch, who was to be opposed if he overrode their interests. Lord North was, if anything, a moderate Tory – a grouping associated with the landed gentry – but would not have been fenced in by this label. By the 1780s, however, the political parties were starting to become more clearly defined, with economic reform and the reduction of royal power at the heart of the revitalized Whigs’ ideology.

Charles James Fox, their leader, was a colossus of the House of Commons – the subject of more political cartoons than any other man of his time. A hostility existed between Fox and the king that was more deep-seated than mere partisan difference, for they were also polar opposites in temperament – while the monarch was a man of markedly moderate habits, Fox was the ‘hero in Parliament, at the gaming-table, at Newmarket’.[13] According to the king, Fox was someone ‘who every honest Man’ would wish ‘to keep out of Power’; which is why the prospect of such an individual leading his government was almost too painful to contemplate.[14]

It was Henry Dundas, the Lord Advocate, who first proposed William Pitt, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, as a candidate to replace Shelburne. As the second son of the late Earl of Chatham – Pitt the Elder – the younger Pitt certainly had pedigree, even if he lacked experience. He had entered parliament only two years earlier, aged twenty-one, as a protégé of Sir James Lowther. (‘Appleby is the Place I am to represent,’ he had written to his mother, ‘and the Election will be made (probably in a week or Ten days) without my having any Trouble, or even visiting my Constituents.’)[15] Shelburne, while resigning from office, suggested to the king that he might consider inviting Pitt to form a ministry. After putting this idea to the young man, the king reported that he had responded with a ‘spirit and inclination that makes me think he will not decline’.[16] Pitt spent the evening of 24 February with Dundas, trying to work out whether a working majority in the Commons was within his grasp. ‘I feel all the difficulties of the Undertaking and am by no means in Love with the Object,’ Pitt told his mother the following day. ‘The great Article to decide by, seems that of numbers.’[17]

Dundas next asked John Robinson, whose knowledge of the shifting sands of parliamentary loyalties was unrivalled, to compile a breakdown of those MPs who were likely to support Pitt, and those who would likely oppose him. The plot to bring Pitt into power was a profound secret. To avoid raising suspicions, Robinson asked Richard, as a mutual friend – for Richard knew Dundas fairly well, not least as another of Anne Lindsay’s admirers – to carry the completed document from his house at Sion Hill, near Brentford, to Dundas’s residence in Leicester Square, so that he himself ‘might have no communication with the Advocate’.[18]

If Anne Lindsay’s account of 27 February is to be believed, the day might have ended quite differently. She would describe the following story as a ‘whimsical little instance to prove on what trifling circumstances important matters in the line of politicks often hinge’. That morning Richard, on his way from John Robinson’s house into town, had unexpectedly dropped in at Harley Street while she was getting dressed, and sent up a note asking her to come down immediately, since he had something important to tell her:

One pin was necessary to tuck up my hair, and to change a gown all over with powder for a clean one. I hurried below, and found him with his watch in his hand, departing. ‘O! what may not these five minutes delay have cost,’ said he. ‘Pitt has not seen this canvass … I have this instant got it, it is triumphant! He promised to be with the King as 11 o’clock struck, it wants but three minutes of it; if he is not gone, he is our Minister … God bless you!’ And off he rushed. Half an hour brought him back with a dejected air. ‘Alas!’ said he, ‘I was too late. He had set off five minutes before I reached his house, leaving this note: Had the canvass been favourable you would have been here. I must decline; perhaps ’tis best.’[19]

Far-fetched though this tale might sound, it seems likely that some version of it took place. John Robinson himself, in a letter to Charles Jenkinson, alluded to a last-minute setback when he described how a ‘ray of Light’ which might have persuaded Pitt to form a ministry ‘came forward a few Hours too late’.[20] George III now approached Lord North, who refused to lead, but agreed to serve in a coalition cabinet; all of which is how, on 3 March, the king came to offer the reins of government to his arch-enemy Fox, on condition that an independent peer nominally headed the ministry. But Fox would not serve under any prime minister except the Duke of Portland, who was unacceptable to the monarch.

During this nail-biting time, Robinson was confined to his country residence by gout. (Anyone wondering how gout might justify his absence from Westminster at such a critical moment need only examine Gillray’s depiction of the illness, in which some infernal creature sinks its fangs and talons into the swollen foot of a sufferer.) On 14 March, after the nation had been without a prime minister for three weeks, Robinson wrote to Jenkinson, who was in close contact with the king, suggesting that he make one last attempt to ‘set the Wheel a-going thro’ Atkinson, with the Advocate & Pitt’.[21]

The gout, which tormented many eighteenth-century gentlemen of a certain age.

Wellcome Collection

Two days later, the king reluctantly agreed to let the Duke of Portland form a ministry, but refused to deal directly with him, only through Lord North. Portland was at last granted an audience on 20 March, but admitted he could not yet name his cabinet; George III, sensing an opportunity, dispatched a one-line letter: ‘Mr. Pitt, I desire you will come here immediately.’[22] The next day, Portland again waited on the monarch, who refused even to glance at a partial list of the cabinet, insisting on every post being filled before he would look at it. ‘The D. of P. has been with the King & they have parted angrily,’ Richard told Robinson that night. ‘Demands, no less than Honours & Power unlimited! If the Parties quarrel clearly between themselves, the thing will do. If the King quarrels with them, it will not do.’[23] Pitt, meanwhile, was hoping for signs of support in the Commons, but none were forthcoming, and he again turned down the premiership. Richard wrote on 25 March:

The blossoms of yesterday are finally blasted. Upon a very recent conversation between Mr. Pitt and the Advocate, the latter gives the business up as wholly at an end. All that can remain will be to give such support as one can to the Government, for by Heaven I am convinced there are not materials in the country to form another. This young man’s mind is not large enough to embrace so great an object, and his notions of the purity and steadiness of political principle absolutely incompatible with the morals, manners, and grounds of attachment of those by whose means alone the Government of this country can be carried on.[24]

The king held out for another week as he pondered the ‘cruel dilemma’ of being forced to appoint a ministry made up of men ‘who will not accept office without making me a kind of slave’.[25] Not for the first time, he contemplated abdication. On 1 April, after five weeks of political deadlock, George III signalled that the new cabinet would be expected at St James’s the following day to kiss hands. John Robinson commented: ‘Poor King, how very very much does His Situation deserve pity.’[26]

BEFORE THIS DISRUPTION, Henry Dundas had been working on a bill to place the East India Company and its territories under tighter government control. It would be hard to overstate the importance of the Company to the commercial life of Britain at this time. Some historians have characterized it as the first multinational corporation, but it was so much more powerful than even this description might suggest, possessed of a vast private army with which it had subjugated emperors and princes; and thus huge swathes of the Indian subcontinent were effectively ruled from nondescript offices in the City of London.

Dundas had been taking an interest in Indian affairs since 1781, when he was appointed chairman of a secret committee set up to investigate the war against Hyder Ali, the great Sultan of Mysore; before long his scrutiny would extend to every aspect of the Company’s activities. But when he finally placed his India Bill before parliament, on 14 April 1783, the new ministers made it clear that they would not give it their support, and thus it was still-born.

Although the Duke of Portland was officially prime minister, his ‘indolent habits and moderate capacity led him to relish power rather than to seek it’ – this was Anne Lindsay’s pithy analysis – which meant that Charles James Fox was leader in all but name.[27] In those days, before the existence of a professional civil service, or salaries for MPs, ministers relied upon royal patronage to reward those who laboured on the government’s behalf. The king so hated this particular ministry, however, that he simply shut down the supply of offices, sinecures, titles and pensions that were needed to keep the cogs of administration well greased. ‘I do not mean to grant a single Peerage or other Mark of Favour,’ he told Lord Shelburne.[28]

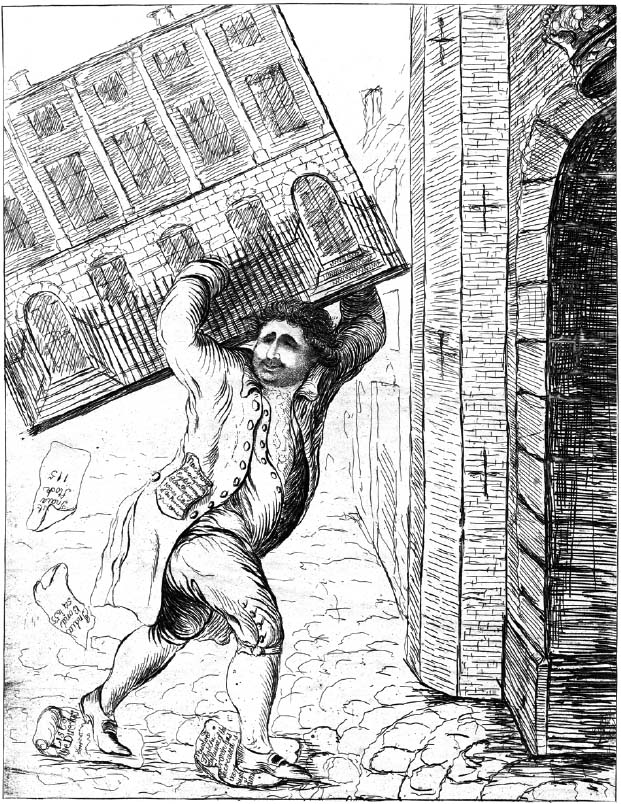

It would turn out there was good reason why Fox had given Dundas’s India Bill such short shrift in the spring, as he harboured plans for legislation of his own. Fox placed his India Bill before the House of Commons on 18 November. One measure alone contained enough powder to touch off a massive blast in the cellars of East India House; this was the plan to establish a board of seven commissioners, nominated by parliament, who would have the ‘power to appoint and displace officers in India’.[29] To those who detested Fox, or owned East India Company stock, the bill seemed like the ‘boldest and most unconstitutional measure ever attempted’, a brazen scheme to steal the patronage of the Company and put it to work for his personal political ends.[30] The bill’s first reading was on 20 November, and Fox made it clear that he intended ‘to take the House, not only by force but by violence’.[31]

Richard led the East India Company’s resistance to Fox’s India Bill from the start. On 21 November, at a Grand Court held at the Company’s headquarters on Leadenhall Street, he was appointed to a committee of nine proprietors tasked with defending its rights and privileges; but the chairman of the group immediately fell ill, leaving Richard to step into his shoes. The committee’s first undertaking was to compose a strongly worded petition, objecting to the seizure of ‘lands, tenements, houses, warehouses, and other buildings; books, records, charters, letters, and other papers; ships, vessels, goods, wares, merchandizes, money, securities for money, and other effects’ that was threatened by Fox’s bill.[32] This document was placed before the Commons three days later.

A Transfer of East India Stock, in which Fox makes off with East India House.

Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

The committee’s next task was to disprove Fox’s claim that the Company was £8 million in debt – an assertion which had caused the price of its stock to slide from £138 to £115 in just three days. By the time of the bill’s second reading, on 27 November, Richard had compiled a detailed report on the Company’s finances – by his reckoning, it was almost £4 million in credit. At the start of the debate, two lawyers presented Richard’s conclusions from the bar of the House of Commons. Fox then stood up to give his response. The report, with ‘many things inserted, which ought to have been omitted, and many things omitted, which ought to have been inserted’, was a staggering distortion of the Company’s affairs, he asserted, and he condemned the men who had dared to produce ‘an account so full of imposition and absurdity’.[33] Fox’s display of righteous indignation dazzled his enemies; William Pitt, leading the opposition, complained that he had ‘run through the account with a volubility that rendered comprehension difficult, and detection almost impossible’.[34] When the House divided, at 4.30 a.m., the ministry prevailed by a decisive 229 votes to 120. ‘The shameful impositions of the Company, in the printed state of their affairs, were completely detected and exposed,’ said one newspaper. ‘Opposition seemed planet-struck.’[35]

I find this incident fascinating because it shines light on a critical flaw in Richard’s character, one that might be considered the source of many of the Atkinson family’s future troubles. Francis Baring, writing to Lord Shelburne two days later, pinpointed Richard’s role in the drubbing:

Atkinson has brought Mr. Pitt into a scrape by endeavouring to prove too much, & of which he was warned at the outset; but it ever was the case with him, his talents & imagination are so rapid that they always run away with judgment; & at this moment instead of taking ground which is sound, defensible against every attack, & sufficient for the purpose; he is endeavouring to elucidate & support, various articles which he must know himself to be moonshine.[36]

On 3 December, as Fox named his board of seven commissioners – all of whom, it was muttered, were better known at Brooks’s Club than in Bengal – Pitt conspicuously stayed away from Westminster. At its final reading in the lower chamber, on 8 December, the India Bill passed by a majority of more than two to one, and Fox was able to carry it up triumphantly to the House of Lords.

JOHN ROBINSON HAD stayed away from Westminster while the India Bill passed through the Commons, conveniently blaming his absence on a further attack of gout, in part to avoid the very public treachery of being seen to vote against Lord North. Once again, Richard acted as Robinson’s go-between with Henry Dundas and others; this explains why much of the tiny amount of correspondence to have survived from this deepest of political intrigues is in Richard’s handwriting.

The India Bill’s passage through the Lords, it would seem, was a foregone conclusion. ‘We are informed that Ministers have an ascertained majority of two or three and thirty Peers,’ reported the London Chronicle.[37] However the king, and many others, saw Charles James Fox as a dangerous man who had to be stopped; and so the battle lines were drawn for the greatest test of the respective powers of the monarch and parliament since the Glorious Revolution. On 1 December, Lord Chancellor Thurlow – who strongly opposed the bill – placed a memorandum before the king which professed ‘to wish to know’ whether the legislation appeared to ‘His Majesty in this light: a plan to take more than half the royal power’. Thurlow’s message also suggested that were the king to take the highly unusual step of revealing his feelings on this matter, ‘in a manner which would make it impossible to pretend a doubt’, the bill would face defeat in the House of Lords.[38] Two days later, Richard learnt that the Chancellor’s communication with the king had produced the desired effect. ‘As far as I can learn or judge,’ he told Robinson, ‘every thing stands prepared for the blow if a certain Person has Courage to strike it.’[39]

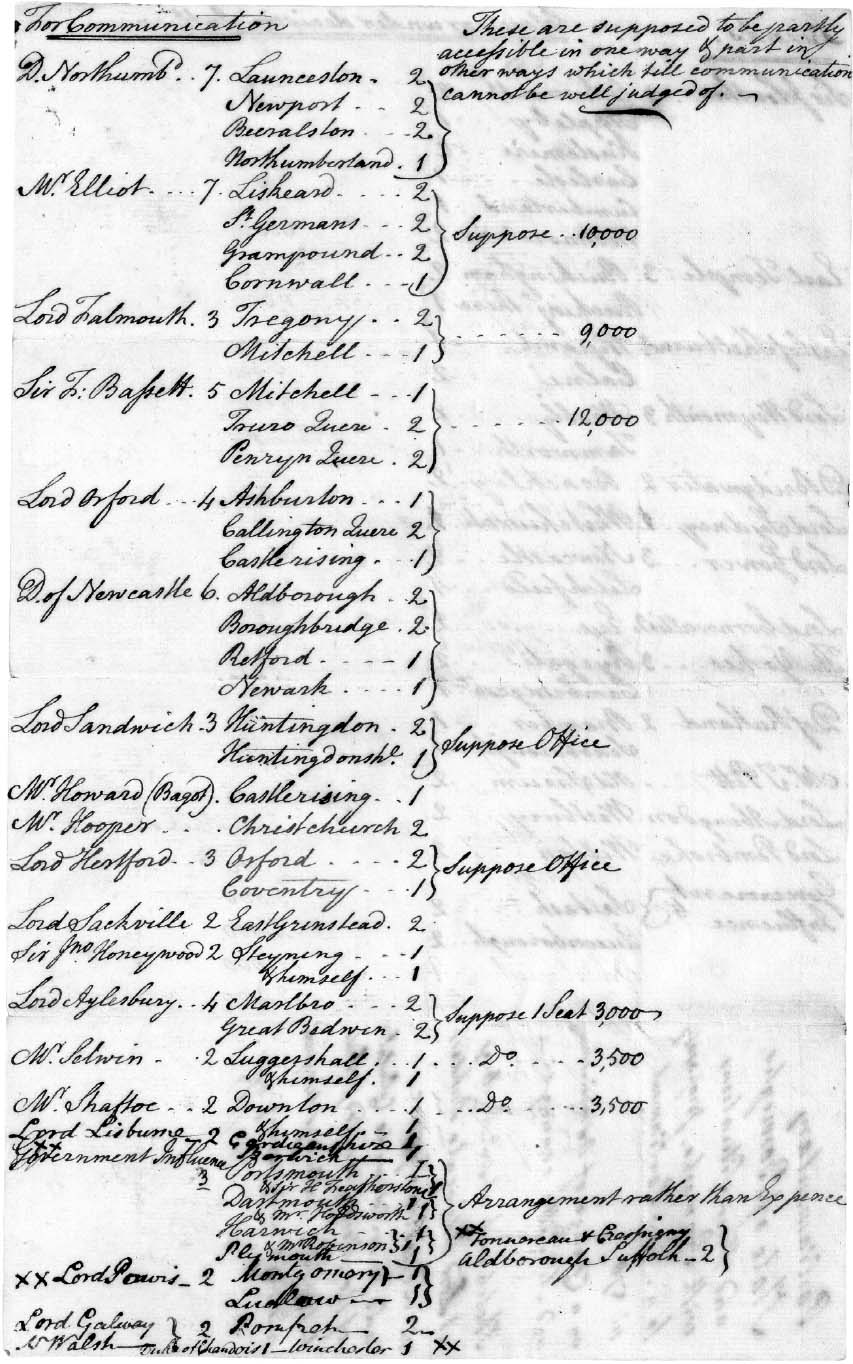

That ‘certain Person’ was, of course, George III. But he would not strike the ‘blow’ until William Pitt had indicated his readiness to take office; and first Pitt needed to be sure that a parliamentary majority lay within his reach. On the evening of 5 December, Robinson received a message from Dundas, urgently requesting an analysis of the House of Commons. ‘That Night I worked until past 2 & the last Night until towards 3 this Morning, & both Days, except some little Interruptions, until this Moment that it is finished as well as may be in such a Hurry for my Pen has been constantly driving all the above mentioned space of time,’ Robinson wrote to Jenkinson, in evident haste, two days later.[40]

What Robinson omitted to say was that Richard was also present at Sion Hill, his pen likewise ‘driving’ round the clock to compile the document. We know as much because a rough version of this highly speculative survey, in Richard’s handwriting – one page is splashed with what looks like strong black coffee – exists in the family archive of John Robinson’s descendant, the Marquess of Abergavenny. The two men drew up a list of all 558 parliamentary seats, dividing them into four columns headed P, H, D and C, for ‘Pro’, ‘Hopeful’, ‘Doubtful’ and ‘Contra’, according to the sitting member’s likely stance towards a Pitt ministry.[41]

Richard carried the finished document across town to Dundas on the evening of 7 December. ‘I found our Friend last night & looked over the Paper with him,’ he reported back to Robinson, in deliberately veiled language. ‘Although at the first Blush it had not appeared quite so favorable as had been expected, yet on fuller consideration and going through the whole it was admitted that the turn was throughout strongly given to the unfavorable Side & that there was no manly ground of apprehension.’[42]

THE INDIA BILL received its first reading in the House of Lords on 9 December. Richard, who had prepared a petition from the East India Company for presentation during the debate – another ‘Bomb from the India House’, as John Robinson put it – briefed Lord Thurlow first at his house in Great Ormond Street.[43] The following day, after learning that Pitt was ready to ‘receive the burthen’ of office, George III instructed Lord Temple to make peers aware of his strong aversion to the India Bill. Richard summarized these manoeuvres for Robinson, ending with the royal trump card: ‘He has given authority to say (when it shall be necessary) that whoever votes in the House of Lords for the India Bill is not his friend.’[44]

The king’s intervention had an electrifying effect. On 15 December, the East India Company’s lawyers gave evidence in the upper house for eleven hours before seeking permission, as it neared midnight, to continue the next day; somehow the opposition managed to muster a majority of eight votes on a motion to adjourn the debate, in effect postponing the decisive division on the second reading. Around thirty peers, it seemed, had switched sides.

That same evening, four conspirators – William Pitt, Henry Dundas, John Robinson and Richard Atkinson – discussed tactics over a secret dinner hosted by Dundas at Leicester Square. In a note calling Robinson into town, Richard explained that the covert nature of the gathering was ‘lest the measure in agitation should be guessed at’.[45] This ‘measure’ was a general election, and their objective was to identify the means by which a majority in the House of Commons might in due course be obtained.

It is at moments such as this that the gulf between parliamentary democracy then and now seems at its most unbridgeable. The minutes of this and subsequent meetings, which are in Richard’s handwriting, identify thirteen landowners who between them controlled forty-one seats that might be purchased with royal patronage; sixty-nine seats that might be bought using a combination of money, offices and honours; and sixty-five seats for which money alone would suffice. Even Robinson, no wide-eyed innocent, was horrified by the projected expenditure – £193,500 for 134 seats to ensure a majority – and he would distance himself from the figures. ‘Parliamentary State of Boroughs and their Situations with Remarks, preparatory to a New Parliament in 178- on a Change of Administration and Mr. Pitt’s coming in,’ he noted on the minutes. ‘Sketch out at several Meetings at Lord Advocate Dundas’s in Leicester Square and a wild wide Calculate of the money wanted for Seats but which I always disapproved and thought very wrong.’[46]

Sixty-nine parliamentary seats and their proprietors, in Richard’s handwriting.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Marquess of Abergavenny

The struggle reached its climax on 17 December. Fox had tabled an emergency resolution to protest against the king’s flagrant violation of the rule that he could only operate through his ministers, and this business in the lower chamber would coincide with the crucial vote on the India Bill along the corridor in the House of Lords. At midnight, while both houses were still in the throes of debate, Richard dashed off a note to Robinson with some unexpected news. ‘My dear Sir,’ he wrote, ‘I am dragged into the India Direction.’ Earlier that day, during a meeting of the proprietors at East India House, while Richard was in a side room dealing with an urgent query from Lord Thurlow, he had without warning been nominated to fill one of two vacancies caused by the resignation of Foxite directors. ‘Tomorrow I will breakfast in Leicester Square & take a Servant with me to send out to you. You stand high with Mr. Pitt about which I have more to tell you than I can well write,’ he concluded.[47]

At noon the following day, Richard sent Robinson a high-spirited message to say that the India Bill was demolished, defeated in the Lords by a majority of nineteen: ‘What a constitution of Character this is!’[48] That evening, as Portland, Fox and North were in conference, a messenger brought a letter from George III demanding the surrender of their seals of office. ‘I choose this method,’ explained the king, ‘as Audiences on such occasions must be unpleasant.’[49]