THIRTEEN

![]()

The Newcastle Attorney

I WISH I COULD describe Richard’s final months in greater detail. Dorothy nursed him during this time, and she must have written to Bridget at Temple Sowerby with news of his decline – but no such letters have survived. As for what caused Richard’s death, we cannot know for sure, but it seems likely to have been tuberculosis. (An explanation supported by Nathaniel Wraxall, whose memoirs – one of the livelier commentaries on the events of the period – refer to Richard being carried off ‘in the vigour of his age’ by a ‘feverish and consumptive complaint’.)[1]

I was on the point of accepting that there was no more to know on the subject when I came upon the brief description of Richard’s dying moments, including his last words, in a letter from Lady Elizabeth Yorke to her sisters in Paris. It was a wonderful archival discovery, as well as a vexing one; for while the first sheet of the letter had been preserved, the rest had gone astray. Elizabeth told how, on hearing news of Richard’s death, and feeling it her ‘duty to do all to his niece that I could have done for a sister’, she had rushed to Dorothy at Fenchurch Street: ‘Oh my dearest Sisters may you never enter that house again! for if I found it so melancholy, so chearless, what must it appear to you! I found her in the greatest affliction, the gloomy appearance of the House & the want of air, made me immediately consider that the best thing I could do would be to carry her’ – and here the page ends …[2]

Many years later, Anne would recount the rest of this sad episode in her memoirs. Elizabeth had postponed a ball that she was about to give in London; instead she bundled Dorothy away to Hertfordshire in a well-intentioned attempt to ‘restore her spirits’, recruiting another guest to ‘read Shakespeare to her from morning to night’. Evidently this treatment failed, however, for Dorothy had left the Yorkes earlier than planned, and hurried home to her mother in Westmorland – conduct which made her guilty, in Anne’s opinion, of ‘unpardonable’ ingratitude.[3]

RICHARD’S DEATH left me bereft. He was such a dynamic personality, such an incurable optimist, and it seemed unthinkable that he would no longer be present in this story. (Although, as we shall see, his influence would reverberate down subsequent generations of the Atkinson family as they grappled with his complex legacy.) By chance he was the same age as me, almost to the month, when I came to write about his death – a coincidence that added a frisson to my emotional response. I certainly felt humbled by how much he had packed into his forty-six years.

Richard’s character had embodied some startling contradictions. Indeed, the gulf between his private and public identities could hardly have seemed wider; on the one hand there was the rejected lover and saintly benefactor, as recalled by Lady Anne Lindsay, and on the other there was the shrewd businessman and political fixer, as portrayed by his critics. (He was also, lest we forget, a slave owner.) The more time I spent in the company of these multiple Richard Atkinsons, however, the easier I found it to see them as facets of the same man. I came to realize, too, that Anne’s memoirs had been written with the rose-tinted nostalgia of thirty years’ hindsight – but, equally, that the ad hominem attacks of the journalists often bore little relation to the target of their derision.

So now we reach what is, for me, the greatest mystery of this story – the discovery of a record so unsettling that it made me wonder whether I would ever know Richard at all. It consists of the copy of a legal deed, which I found within a crumbling volume in the archive of the Registrar-General’s Office at Spanish Town, the old colonial capital of Jamaica. This document states that on 1 May 1785, Samuel Mure agreed to ‘Grant Bargain Sell Transfer Assign and Deliver over unto the said Richard Atkinson his heirs and assigns the following Negro Slaves viz. Betty and her Three Children with the future Issue Offspring and Increase of the said Slaves’, in exchange for £120 of the island’s currency.[4] Betty’s vendor, Samuel Mure, was one of Hutchison Mure’s sons, and managed several of his family’s sugar estates in Jamaica.

For what earthly reason could Richard have felt the need to purchase four ‘Negro Slaves’ less than a month before his death? I turned the question over and over in my mind, trying to imagine scenarios that might have led to so singular a transaction – but ultimately it seemed so domestic, so private, that I could only suppose Betty was Richard’s mistress, and the three children were his children. Then I remembered the letter written by Richard in December 1782, sent to Anne along with the final draft of his will, in which he had expressed a desire to throw his ‘whole Heart open to her’ and to reveal ‘its most secret Sensations’. As attentive readers may recall, he had continued in the same intimate vein: ‘The Consciousness that her Eye must review it would be sufficient to keep out all the black Family, & as to human Frailties, the Heart knows much less than mine that does not know that under the Influence of a generous confidence they would become the very Cement of its best Happiness.’[5]

The first time I read that passage, I must confess, my eyes slid over it – I suppose I thought Richard’s reference to ‘the black Family’ was an obscure figure of speech. It had not crossed my mind that he might mean a black family of his own, for I knew he had never visited Jamaica – the dense paper trail of his letters in all the archives left no gap long enough to allow for such an absence. But black servants could be found in many wealthy London households at this time, and it seems likely that the Mures brought Betty over to work for them; she must at some point have entered into a relationship with Richard. According to the laws of slavery, the offspring of an enslaved female automatically belonged to her owner; so presumably, through his deathbed purchase, Richard hoped to spare Betty and the children the fate of being returned to the West Indies. (If he had wished unambiguously to guarantee their liberty, he could have freed them in a codicil to his will – which would, however, have carried the drawback of declaring their existence to the world.)

The whole subject is deeply uncomfortable, especially as the scarcity of information has driven me so much further down the path of conjecture than I would like. The story of Betty and her family raises so many questions, none of which, I suspect, will ever be answered – there is too little information to go on. Where was she born? Where did she grow up? How did Richard treat her? What were the children called? Did Richard make provision for them after his death? Did they go on to have families? Might any of their descendants be alive today?

RICHARD’S BODY WAS INTERRED beneath the middle aisle of Brighton’s ancient parish church of St Nicholas of Myra, patron saint of merchants, on a grassy hill high above the English Channel. His death automatically triggered several elections – within weeks a new MP for New Romney, a new alderman for Tower Ward and a new director of the East India Company had replaced him. As the economist Dr Richard Price wrote to the former Lord Shelburne, now Marquess of Lansdowne: ‘Your Lordship has seen in the Newspapers that Alderman Atkinson is dead. He has made a great noise and bustle, and rose from a mean station to wealth and honours. But what does it all signify?’[6]

The Morning Chronicle ran an admiring obituary on 9 June, observing that Richard had arrived in London a ‘mere adventurer, unsustained by any inheritance, by few family friends of any power, and by no acquisitions, which education imparts, but common penmanship and arithmetick’, and had managed through ‘good sense and persevering industry’ to rise from the ‘bottom of society to the summit of affluence’.[7] Other newspapers ran less respectful pieces, which caused a few readers to leap to his defence. ‘The fidelity with which the Alderman executed all his contracts with government is worthy of notice,’ observed one correspondent to the Public Advertiser. ‘Whatever mistakes or misconduct may be attributed to the commanders by sea or land employed by our then Ministry, no part of their ill success was ever attributed by them to any neglect of the late Alderman not fulfilling his contracts with punctuality.’[8]

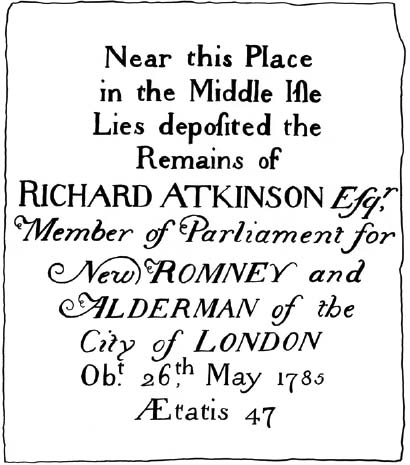

Richard Atkinson’s tombstone in Brighton parish church.

Richard had planned his will to be the mechanism by which he would enrich his closest friends and elevate the next generation of the Atkinson family. As you might expect, it was highly detailed; it was also full of the windy repetitions and circumlocutions with which such documents abound. In essence, though, Richard expected the produce of his two Jamaican estates to fund annuities worth more than £5,000 a year. Lady Anne Lindsay, Lady Margaret Fordyce and John Robinson would each receive £700 a year; his brother Matthew Atkinson, sister Margaret Taylor and sister-in-law Bridget Atkinson would each receive £200 a year, as would Captain John Bentinck’s son William; while his nine nieces and George Fordyce’s two daughters would each receive £200 a year as soon as they came of age. Richard also anticipated the estates generating surplus income, above what was needed to pay the annuities, which would accumulate into a substantial fund; lump sums of £3,000 would be paid from this fund to each of his eight nephews when they came of age, and any remaining money would be divided equally between his nine nieces and any daughters Lady Anne Lindsay might end up having. The Bogue estate would eventually pass to the sons of his brother George, while the Dean’s Valley estate would go to the sons of his brother Matthew. It was soon to become all too clear that in attempting to spread his wealth so widely, Richard had disastrously overreached himself.

Anne and Margaret returned to London three weeks after Richard’s death, filled with remorse at their failure to visit him before it was too late. Their family attempted to absolve them of their guilt. ‘Do not, do not repine my dearest sisters that you were not at Brighthelmstone during the last moments of our much loved, much regretted Friend,’ wrote Elizabeth. ‘I feel your distresses & know how poignant your grief must be.’[9] Their brother, Lord Balcarres, insisted that their conduct had been perfectly correct: ‘Whatever Regret you may have for not being present at his Dissolution, you have certainly no Room for reproach, and if you had come over I am certain it would have fretted him.’[10]

The size of Richard’s fortune would be the cause of much gossip over the following weeks – £300,000 was a figure bandied about in the press – and the wax seal on his will had barely been broken before scurrilous rumours started circulating about the nature of his friendship with Anne, especially given the provision made for her non-existent daughters. ‘The WILL – and the AFFAIRS. What mistakes and pleasantry have Lady Anne Lindsay’s children and Atkinson’s will occasioned!’ exclaimed the Public Advertiser.[11] As she would herself observe: ‘Such generous conduct as Mr. Atkinson’s is not made for the comprehension of the world.’[12]

Everywhere Anne went, people congratulated her on her inheritance – yet she felt ‘bent down to the ground by private sorrow’.[13] Her memories of this time would remain raw for the rest of her life. ‘Do I pretend to have a heart?’ she would write years later. ‘Am I not a stone that I should have hesitated and postponed my return when his health became a question? Would he not have gone to the end of the world to do good to mine? O! my kind friend! why had not you the shoulder of the person you loved to lay your poor head on?’[14]

FOR THE MURE FAMILY, Richard’s death was a catastrophe. While their late partner had been building the reputation of their firm as one of the foremost merchant houses in the City of London, the younger Mures – Robert and William – led a bone-idle existence, shooting and fishing on their elderly father’s estate in Suffolk. After the mansion at Great Saxham burnt down, in 1779, the family had moved into the stable block, on to which two wings had been added, giving it the air of an Italian villa. Apparently it was a dull household. ‘Mr. Mure’s daughter and sons didn’t seem to me to be very fond of laughing,’ recalled the Comte de La Rochefoucauld, who stayed at Great Saxham during the summer of 1784. ‘The worst drawback there in going to dinner with Mr. Mure is the great length of time he stays at table, generally three and a half hours. I once sat there five hours, without leaving the table, just eating and drinking.’[15]

In Richard’s absence, the Mures soon fell into financial difficulties, and they immediately set about talking down the size of his estate, a good deal of which would have to come out of the assets of the partnership. ‘As very much depends upon the state of Mr. Atkinson’s Personal Property we are busy in making up his accounts,’ Robert Mure wrote to Lord Balcarres, a trustee of Richard’s will, barely a week after his death. ‘I have to observe that from the very large sums he had expended upon the Improvement of his Estates in Jamaica they will be very much increased in Value, his Personalty proportionately diminished.’[16] Two months later, the Mures would attribute their cash-flow problems to Richard having taken sums ‘amounting to £78,000’ out of the house between the time of writing his will and his death.[17] This was a foretaste of the wrangling that would consume the energies of an entire generation, and ultimately serve the interests of no one – save the lawyers.

BRIDGET ATKINSON had spent little time in her brother-in-law’s company – the last occasion on which I can say they certainly met was in 1776 – yet his demise came as a heavy blow. Following the death of her husband, George, she had gratefully accepted Richard’s offer to act as protector to her eight children: Dorothy, Michael, George, Richard, Matthew, John, Bridget and Jane. Already her two eldest sons had departed for the colonies. Michael had sailed for India in 1781; George, meanwhile, had gone out to Jamaica in the summer of 1784, and was now employed at the merchant house of Mures & Dunlop in Kingston, from where he could also keep an eye on his uncle’s estates. (He took his hound out with him; Bridget’s pocket account book records the purchase of a dog collar, engraved ‘Jock – G. Atkinson – Deans Valley’.)[18] For the younger Atkinson boys, lacking their uncle’s patronage, their futures were suddenly filled with uncertainty.

Bridget and her brother-in-law Matthew were both appalled when they learnt how much Lady Anne Lindsay stood to gain from Richard’s will; they saw her as an undeserving heiress, and set out to frustrate her claim. Anne, not surprisingly, saw the matter in a different light: ‘The family of Atkinson having seen their brother but once in the course of twenty years, were not in the habit of forming expectations from him, till his invitation of Dolly awakened them. They now affected to be mortified at the destination of his property.’[19]

The Mures started putting about rumours that their late partner’s estate was too insubstantial to support his legacies. Matthew Atkinson and his brother-in-law George Taylor – who were both executors of Richard’s will – travelled south for a potentially tense meeting at Fenchurch Street in March 1786. ‘I am anxious to know upon what terms Messrs. Mures & my uncles parted I fear not well,’ Dorothy wrote to Bridget, from Newcastle, on 31 March.[20] But the Mures evidently smoothed over the Atkinsons’ concerns, for Dorothy wrote joyfully to her mother a few days later:

I cannot let you remain a moment in ignorance of what I have learnt from my uncle. There is not the smallest doubt but every annuity and every legacy will be paid to a farthing – there are no chancery suits but imaginary ones – no difficulties but the like – and Mr. Taylor says that every one of the Mr. Mures have behaved with more kindness, attention and patience than he can describe. You may set your heart quite at rest – what needless vexation have we suffered.[21]

The Lindsay sisters would also soon experience the Mures’ double dealings. In the eyes of the world, Anne was a wealthy heiress; wherever she went, she sensed once-indifferent bachelors sizing her up anew. (The Morning Herald commented with cheerful malice on her ‘ostentatious’ coach: ‘It surely is a splendid compliment to Mr. Atkinson’s hearse!’)[22] But her true situation was far from clear, for she was yet to receive a penny of her legacy; and so she was aghast when John Smith, Richard’s lawyer, informed her that the Mures were planning a raid on their late partner’s estate to pay off ‘old debts’ of more than thirty years’ standing. It might be necessary, Smith warned, for her to make ‘some concessions’.[23]

Soon afterwards, Anne and Margaret had a bizarre meeting with Robert Mure. Anne later wrote:

Never did I see so strange a wrestle amongst the good and bad qualities as appeared in his countenance. He entered covered with purple blushes, and a few tears, which the recollection of the benefactor of his House forced from his heart to his eyes, giving him the aspect of a red cabbage throwing off the dews of the morning; but the good emotion departed with the tears, and he became hard and collected like the said cabbage.[24]

Mure stammered that he and his brother William were planning, through the courts if necessary, to challenge Richard’s estate for the stock he had acquired through floating the government loan of 1782, of which he had set aside £30,000 for Anne’s benefit. The Mure brothers did concede that their father Hutchison, as senior partner, had told Richard that he could dispose of the stock as he pleased, but the permission had been granted verbally, not in writing, and therefore they considered it the property of the house.

AT TEMPLE SOWERBY, on 10 August 1786, Bridget locked and bolted her bedchamber door as usual before turning in for the night. She woke at about two in the morning to feel her bed shaking, ‘as if somebody had got from under it’, and the floorboards cracking, ‘as if somebody was walking on them’. Were she to live in a land where earthquakes occurred, she wrote in her diary, she would suppose this to have been one – but instead she put it down to a ‘nervous Simptom’.[25] The shock would be felt across the northern counties of England, but it is hardly surprising that Bridget blamed it on her nerves, for they were in an unusually jangled state.

A few months earlier, the Atkinson family had hired an ambitious young attorney-at-law, Nathaniel Clayton, to defend their interests against the Mures. Clayton came from a line of Newcastle upon Tyne worthies – his grandfather and uncle had both been mayor – and had started his legal practice in the Bigg Market back in 1778, when he was twenty-two. He was also town clerk of Newcastle, having paid £2,100 for the lease on that office in June 1785. The fees earned by the incumbent were quite nominal; its main advantage lay in the valuable inside knowledge to which the town clerk was privy through his dealings with the council.

Shortly after accepting the Atkinsons’ brief, Clayton had fallen in love with Dorothy, who was staying with friends in Newcastle. His earliest letters to her still exist. The first starts: ‘Madam, I cannot reconcile it to myself to delay a Declaration of my unalterable Regard, and that it has become absolutely essential to my Happiness to obtain your Confidence & good Opinion …’[26]

Dorothy’s reply has not survived, but it seems to have caused him pain. ‘Dear Madam,’ began his second letter:

The Rapidity with which my favourable Opinion of you grew into Esteem, and that Esteem into Love, I have felt but cannot describe. I have urged on the Decision of my Fate with inconsiderate Rashness, & have now only to deplore how vain they are who teach that cruel Certainty is more tolerable than a state of anxious Doubt. My Heart has also undergone a solemn & a strict Examination. I find it unchangeably yours, and that it cannot be estranged, til it shall cease to beat.[27]

This time Dorothy must have given her admirer cause for hope, for his next letter is much more playful:

My most amiable Girl, I am much at a Loss to justify my giving you the Trouble of receiving my Letters, otherwise than by imputing it to that Propensity which Lovers have to write as well as talk Nonsense to their Mistresses, & to the hope that, as I have been pardoned for teazing my Angel with Declarations of my Love for her, I shall also experience her Lenity, when I more solemnly, in black & white, assure her that she is the dearest Creature upon Earth & that I am the most enamoured Swain.[28]

Bridget reacted badly to the news of her daughter’s attachment – perhaps forgetting her own mother’s opposition to her engagement nearly thirty years earlier – which in turn caused Dorothy to hesitate. ‘I begin to think I have been too hasty with regard to Mr. Clayton,’ she wrote to Bridget. ‘I perceive an impropriety in marrying whilst our family affairs are in such an unsettled state. I shall be guided by your opinion, for I can with truth assure you my dear mother that I never will marry without your intire approbation.’[29] But Bridget did not stand in the way for long, offering Dorothy her acquiescence at the end of October 1786:

I have nothing to disapprove in Mr. Claytons conduct to you or to myself only I am very Sorry he ever distinguished you by his regard. If you continue in the same mind and wish for my consent you shall have it most certainly only pray do not Let Mr. Clayton write me any more it affects my Spirits more than you can imagen indeed the Loss of a companion and one I could at times consult upon every Occasion is hard to bear but – to part with a child is scarce supportable and yet a Match which all your Freinds think a very good one a man rising in the World I should not be able to bear my own reflections if I prevent it so God direct you for the best.[30]

Nathaniel Clayton rode over to Temple Sowerby on 22 November, a pouch full of gold rings in his pocket. ‘The Goldsmith appearing to have but little faith in the Measure of thy fourth Finger you gave me I was much alarmed lest that mystical Instrument, which I am to give as an earnest of Happiness & Love, should prove a perpetual Source of Uneasiness by its not being of a proper Size,’ he had written to Dorothy beforehand. ‘From this Dilemma I have however been happily relieved by obtaining a Number of Rings of different Shapes & Sizes for thy Choice, & it will not be an unpleasant Duty on Wednesday Afternoon to try them all.’[31] The following day, they were married in the village church.

The newlyweds immediately set off for London, their purpose being to meet the various beneficiaries of the Atkinson estate and to prevent it from ending up in the Court of Chancery – for chancery suits, often involving matters of inheritance, were liable to drag on for generations, bleeding families dry in the process. One night the Claytons dined with Anne Lindsay; Francis Baring was the only other guest. After they had finished eating, and Baring had left, Anne launched into a tirade about Robert Mure’s ‘iniquitous claims’ upon Richard’s estate, which she believed would prove ‘equally ruinous’ to the Atkinson family’s interests as to her own.[32]

Back at Temple Sowerby, Bridget was furious when she found out who the Claytons had been fraternizing with. Dorothy wrote from lodgings in Charlotte Street:

You tell me you are ‘angry very angry’ that I should listen to what Lady Anne had to say against Mr. Mure. Let me ask you my dear mother how it is possible for me to judge of a cause, without first hearing both sides, the truth of which maxim cannot be more clearly evinced than by your violent prepossession on behalf of Mr. Mure who is making claims upon the fortune and casting reflections upon the memory of my dear uncle, that are neither conscientious nor justifiable – those are not the suggestions of Lady Anne but incontestible facts.[33]

Dorothy and Nathaniel did not enjoy much of a honeymoon. It rained almost the entire month they were in the capital, and their business and social commitments left little time for shopping or other gaieties. After Christmas in Westmorland, they returned to Newcastle to take up residence at Nathaniel’s house on Westgate Street, next door to the Assembly Rooms. ‘The business of today is receiving cards of congratulation,’ Dorothy wrote to her mother on 8 January 1787. ‘Happily it is not the fashion to answer them.’[34] (She was always a reluctant correspondent.) Within weeks, Dorothy had fallen pregnant – a condition in which she would spend a large part of the following two decades.

Nathaniel was called down to London in the late spring on Atkinson family business. George Atkinson – Bridget’s second son – returned from Jamaica in early June, after three years away, and struck up an immediate rapport with his new brother-in-law. Together, Nathaniel and George tackled the legal representatives of Paul Benfield – who of course owned half the Bogue estate in Jamaica. They also dined with John Robinson at Sion Hill. During his stay in the capital, Nathaniel found time to sit for a portrait. ‘My Picture is finished,’ he wrote to Dorothy on 30 June, ‘and looks so smart that I am in hopes beholders will cease to wonder how I obtained the best woman upon Earth for my Wife.’[35]

By August, Dorothy had started to grow cumbersome in her pregnancy. ‘My Dorothy is vastly well,’ Nathaniel told Bridget, ‘but does not move up & down Stairs quite so expeditiously as she has wont.’[36] A ‘sweet little Boy’ arrived in November, and was named after his father.[37] In the spring of 1788, after ‘little Nat’ had safely recovered from his smallpox inoculation, Nathaniel was yet again needed in London.[38] ‘I confess I am not yet so fashionable a husband as to relish these unreasonable absences,’ he told his mother-in-law. ‘I have therefore endeavoured to prevail on Dorothy to accompany me on my next Trip which She has consented to do on Condition that you will take the Boy and be engaged under the penalty of forfeiting your whole Cabinet of Shells to return him on Demand.’[39]

THREE YEARS AFTER his death, Richard Atkinson’s tangled affairs still attracted much prurient interest. In March 1788, James Boswell attended a dinner given by the Earl of Lonsdale at which ‘much good wine’ was taken.[40] One of the guests, Sir James Johnstone, insisted that ‘Alderman Atkinson’ had explicitly mentioned in his will a love correspondence between himself and Lady Anne Lindsay, ‘his own letter consisting of twenty four pages and hers of twelve’, and had left money to her three children, including one with whom she was secretly pregnant while in France.[41] Another guest, Sir Michael Le Fleming, disputed this account. The baronets made a wager, the forfeit being dinner at the London Tavern. Boswell, acting as referee, duly inspected Richard’s will at Doctors’ Commons the following Saturday; but his journal fails to record whether Johnstone was ever required to pay up.

By the summer of 1788, the negotiations around Richard’s estate had stalled. What the various parties did agree was that he had owed his partners about £35,000 at the time of his death – a figure which had since risen to £50,000, including interest and bad debts. Richard had also owed Captain David Laird £16,500, secured as a mortgage on the Dean’s Valley estate – this money was due for repayment in 1792. On the other hand, Richard’s personal effects, including East India stock, his wharf and warehouses at Rotherhithe, and sizeable loans to the Nevill and North families, were valued at £22,000; additional holdings, including shares in the Bessborough and loans to Lord Wentworth and the family of the late Captain John Bentinck, were worth £38,000. With the liabilities of Richard’s estate greatly exceeding its liquid assets, the forced sale of the Jamaican plantations seemed inevitable. For his heirs, this would be the worst possible outcome, since the payment of their annuities depended upon the produce of those estates.

Richard had clearly stated in his will that he managed the business affairs of Lady Anne Lindsay, that he had borrowed almost £20,000 from her funds, and that this money remained hers. It was partly through Anne’s own carelessness that her grip on the funds was less tight than it should have been, for Richard had repeatedly offered to buy her a bureau in which to lock up her financial certificates, reminding her that ‘possession is eleven points of the law’.[42] But she had preferred him to look after them for her; she had also refused to let him reveal her identity when he used her money to fund loans to Lord Wentworth and the Bentinck family. Now she lacked the documentary evidence with which to stake her claims.

Anne was treated shabbily by almost all her fellow heirs; when John Robinson warned her against ‘some intemperance’ such as ‘forcing the sale of the estates’ in order to release the money that was owed to her, she described it as the ‘speech of the Wolf to the Lamb whom he accuses of puddling the stream above, though she drinks below’.[43] Her own brothers offered little support against the bullies. Lord Balcarres, much of whose money was tied up in the Fenchurch Street house, was pressed by creditors from all sides. The next Lindsay brother, Robert, recently returned from India with a substantial fortune, was forced to choose between propping up his sister and his brother; he chose the latter. ‘Whatever my intentions were formerly in your favor in case of a Law Suit I must now retract them,’ he explained to Anne, ‘for unless I step forward to assist Bal – with my whole he is ruined past redemption!’[44] The Atkinson family rejected a proposal devised by Anne’s lawyer, which would have entailed ‘considerable sacrifice’ on her part but prevented the sale of the Jamaican estates.[45] Thus finding herself without a single ‘friend to lean on’, Anne felt she had no choice but to agree a ‘miserable Compromise’ with Richard’s executors.[46] By a deed dated 10 June 1790, she signed away ‘realities, claims, and expectations’ worth by her reckoning around £48,000, so as to secure for herself and Margaret the £700 annuities left them by Richard.

Even once this distasteful business was concluded, Anne failed to find the serenity she craved. ‘I had hoped to have been able to tell you that all our pecuniary plagues were settled,’ she wrote to the politician William Windham, with whom she was in the throes of an intense but ultimately doomed romance. ‘The Partners & Executors of my friend Atkinson, after beating me out of everything, are now quarrelling about the division of the spoils, and will not adhere to their own offers, or submit to arbitration. On this account I find myself most unwillingly obliged to pursue these gentlemen by law for redress. My hopes of ease are at an end, my prospects closed, and life will probably be consumed in the conflict.’[47] These words were more far-sighted than she could ever have imagined.