FOURTEEN

![]()

Taking Possession

TWELVE GENTLEMEN, united by their loathing of slavery, gathered for the first time at the offices of the publisher James Phillips at George Yard, in the City of London, on 22 May 1787. One of them was the civil servant-turned-campaigner Granville Sharp, who had been battling against the institution since 1767, when he managed to prevent Jonathan Strong from being bundled off to Jamaica on board one of Mure, Son & Atkinson’s ships. Sharp had played an advisory role in the important Somerset case of 1772, when, the same week as the Fordyce financial scandal was unfolding, the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, had ruled that slavery was unsupported by the common law in England and Wales. But Sharp’s anti-slavery campaign remained a fringe cause, since so much of Britain’s wealth derived from the West Indies.

Olaudah Equiano first visited Granville Sharp in March 1783. Equiano was a former slave who, as a boy, had been sent by his master to be educated in England; later, after returning to America, he had worked to buy his freedom. He had settled in London in about 1768, considering it safer than the colonies, where the danger of being kidnapped and returned to slavery was ever present. Equiano was moved to call on Sharp after spotting a newspaper report about a legal case then being heard at Guildhall, relating to some events during a transatlantic slave voyage, the facts of which ‘seemed to make every person present shudder’.[1]

Originating in Liverpool, the Zong had set sail from the Gold Coast on 6 September 1781, headed for Jamaica with 440 enslaved Africans on board. The ocean crossing was beset by headwinds, contrary currents and navigational errors, and sixty of the captives had died from fever by the last week of November. As Captain Luke Collingwood observed his ship’s supply of drinking water dwindling, and his valuable cargo perishing, he knew that the insurance policy taken out for the voyage contained a loophole; although those Africans who died from sickness counted as a ‘dead loss’, and were uninsured, compensation would be paid for any who succumbed to what was loosely termed the ‘perils of the seas’. On 29 November, Collingwood ordered his crew to start throwing sick Africans overboard – 132 drowned over the following three days. On 28 December, the Zong anchored at Black River, Jamaica, disembarking just 208 slaves.[2] Back in London, when the underwriters refused to pay the £3,960 compensation that was claimed for the drowned Africans – £30 for each man, woman and child – the Zong’s owners took the dispute to court, arguing that rough seas had ‘retarded’ their ship and ‘obliged’ the crew to jettison its human cargo.[3] From a legal perspective, the case of Gregson v Gilbert was clear-cut – Lord Mansfield admitted that it was the ‘same as if horses had been thrown overboard’ – and the jury found for the shipowners.[4] Granville Sharp later unsuccessfully tried to have the crew prosecuted for murder.

The story of the Zong inspired many people to query the moral basis of slavery for the first time. Thomas Clarkson was a divinity student whose response to the question ‘Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?’ won the prestigious Latin essay prize at Cambridge University in 1785. His dissertation was published the following year as An Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, particularly the African. Clarkson’s tract would prove highly influential – it was said that William Wilberforce, the earnest young MP for the county of Yorkshire, turned his attention ‘seriously to the subject’ after reading it.[5] Wilberforce’s political stirring, however, would occur following a conversation that was said to have taken place under an ancient oak tree at William Pitt’s estate in Kent. The prime minister, witnessing the eloquence with which his friend spoke against the slave trade, urged him to take up the cause in the House of Commons.

Two weeks after first meeting, the twelve abolitionists gathered again, this time to decide what exactly they would be campaigning to abolish – the slave trade or, more all-embracingly, the institution of slavery. They soon agreed that the sheer weight of West Indian interests made the abolition of slavery too ambitious a goal. They also suspected they did not need to aim so high, for the enslaved population was in constant decline across the West Indies, with deaths outstripping births, and planters relied upon new arrivals to keep up their workforces; so were they to succeed in ending the slave trade, the abolitionists realized, they would be ‘laying the axe at the very root’ of slavery itself.[6] Thus the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed, with Granville Sharp in its chair, and William Wilberforce its parliamentary representative.

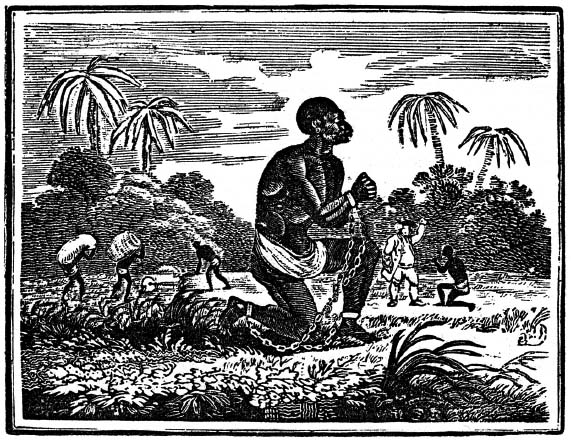

Thomas Clarkson would soon distinguish himself as the committee’s most tireless campaigner. He immediately set out on a five-month investigation of the slave trade, with a focus on the ports of Bristol and Liverpool, where he interviewed hundreds of slave ship captains and sailors. In Liverpool, he spotted a sinister display of iron instruments in a shop window – handcuffs, shackles, thumb screws and a ‘speculum oris’, a surgical device used to force open the mouths of those on hunger strike – and purchased them as props for his public talks. While Clarkson was on the road, the committee launched the anti-slavery movement, sending out circular letters to a largely Quaker list of sympathizers. The pottery manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood was an influential early recruit to the cause; his jasperware cameos of a chained African, imploring ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’, which went into mass production during the autumn of 1787, proved wildly popular, and the ‘kneeling slave’ motif soon adorned bracelets, brooches, buckles, pendants and snuffboxes across the land.

Clarkson had experienced much hostility in Liverpool, so he was amazed by the warmth of his reception in Manchester; while preaching a sermon to the packed collegiate church of this mill town, he was startled to find a ‘great crowd of black people standing round the pulpit’.[7] It was late October, and Clarkson had not seen a newspaper in weeks – otherwise he would have known that anti-slavery petitions were spontaneously breaking out around the country. When Manchester’s petition was delivered to the House of Commons, on 11 February 1788, it was the heftiest yet, containing the signatures of two-thirds of the town’s adult male population. On the same day, William Pitt ordered a committee of the Privy Council headed by Lord Hawkesbury (as Charles Jenkinson was now known) to carry out a thorough investigation of the slave trade.

The iconic image of the ‘kneeling slave’, believed to be by the engraver Thomas Bewick.

Wilberforce was unwell for several months in early 1788, and unable to put forward a parliamentary motion to abolish the slave trade that year. But his friend Sir William Dolben, who was horrified by the cramped dimensions of a slave ship that he had visited on the Thames, succeeded in pushing through legislation that limited a vessel’s human cargo to five heads for every three tons’ capacity up to 207 tons, then one head per ton. Some abolitionists felt that Dolben’s Act legitimized the viewpoint that the slave trade was not fundamentally wrong, merely in need of tighter regulation; but to those in the West Indies who depended upon a constant drip-feed of slave labour, the measure signalled calamity. ‘God knows what will be the consequence if the present Bill is passed,’ wrote Stephen Fuller, the island agent and chief lobbyist for Jamaican interests. ‘It may end in destruction of all the Whites in Jamaica.’[8]

Through the medium of Lord Hawkesbury’s committee, the abolitionists could for the first time place on public record a mass of damning evidence against the slave trade. Clarkson rounded up witnesses, but found that many of those who had been happy to speak out in private were suddenly overcome by reserve, such as one previously garrulous man who explained that as the ‘nearest relation of a rich person concerned in the traffic’, he would ‘ruin all his expectations from that quarter’ if he testified.[9] Among those who did provide powerful statements were the slave captain-turned-clergyman John Newton, whose hymn about moral redemption, ‘Amazing Grace’, was little known at this point; and the ship’s surgeon Alexander Falconbridge, whose Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa offered a first-hand report of its brutalities.

Stephen Fuller, meanwhile, assembled a heavyweight line-up to defend slavery, including five ‘totally disinterested’ admirals who had served in the West Indies.[10] Admiral Rodney claimed there was ‘not a Slave but lives better than any poor honest day labourer in England’, and especially so in Jamaica, where he had never known any planter ‘using Cruelty to their Slaves’.[11] A Liverpool merchant, Robert Norris, likened the middle passage almost to a pleasure cruise, during which the African passengers were treated to delicious meals, entertained with music, dancing and games before dinner, and accommodated in pleasant quarters ‘perfumed with frankincense and lime-juice’.[12] Clarkson and his allies exposed this particular lie by circulating a scale drawing of a Liverpool ship, the Brookes, tight-packed with captives laid out on bare boards. The cargo of 454 enslaved Africans depicted by the plan was in line with the new limit imposed by Sir William Dolben’s recent legislation – but a caption revealed that the Brookes had at one time carried as many as 609 Africans, cramming them in by making them sit in lines between each other’s knees, and lie on their sides instead of their backs.[13]

Hawkesbury’s committee published its report on the slave trade in the spring of 1789. Pitt presented the weighty volume to the Commons on 25 April, which gave MPs less than three weeks to digest its contents before debating the subject. On 12 May, Wilberforce rose to address parliament on the subject of slavery for the first time. From the start, he maintained that questions of personal culpability were irrelevant. ‘We are all guilty – we ought all to plead guilty, and not to exculpate ourselves by throwing the blame on others,’ he advised his fellow members.[14] For the next three and a half hours, in his disarmingly melodious voice, he proceeded to discredit every aspect of the slave trade, ending his speech with twelve propositions in favour of its abolition. It was a mesmerizing performance, which achieved the rare feat of uniting both William Pitt and Charles James Fox in its praise.

Those speaking up for the slave trade based their arguments on cold, commercial logic. Lord Penrhyn, a prominent Jamaican absentee, claimed that £70 million of mortgages on West Indian property would become worthless if the trade were abolished. Alderman Nathaniel Newnham, a member for the City of London, said he could not consent to propositions ‘which, if carried, would fill the city with men suffering as much as the poor Africans’.[15] Over the following weeks, the pro-slavery lobby worked on indecisive MPs, reasoning that the Hawkesbury report was too flimsy a body of evidence to inform so momentous a decision, and convincing them to place the issue before a select committee of the House of Commons. Through the use of such stalling tactics, the abolitionists would time and again be thwarted.

ELSEWHERE IN LONDON that summer, in the studio of the painter Lemuel Abbott just off Bedford Square, a young man sat for his picture. Curiously, Bridget Atkinson’s third son was the first member of my eighteenth-century family of whom I was ever aware. In 1981, when I was thirteen, the portrait of a Richard Atkinson ‘who lived at Temple Sowerby’ came up for sale through Sotheby’s. The black-and-white reproduction in the auction catalogue showed a handsome, serious young man wearing a powdered wig, plain cutaway coat and white shirt with a frilled stock; the vendor was identified as ‘Mrs. Dixon Scott’, who I now know to have been my dad’s third cousin.[16] Although my mother gamely placed a bid, at a time when she could ill afford it, the price rose way beyond the estimate. I can still recall my disappointment on being told that my namesake’s picture had been bought by a nameless collector.

Shortly after his portrait was finished, Dick sailed to Madeira to take up a position working for a British wine merchant. Four hundred miles off the coast of Africa, this Portuguese island was less remote than it might sound, for it was an important stopover on the shipping routes to both the East and West Indies. Bridget packed Dick off with various home comforts, including some cured meats. ‘Your Hams were presented to Mr. Murdoch the only Partner at present resident in the Island & with whom I live,’ he wrote on 6 September 1789, shortly after his arrival. ‘I have a couple of rooms at a small distance from & on the opposite side of the street from the House; the one fronts to the street down which there is a fine cooling streem of water always runing, the other which is my bedroom looks into a small garden in which I employ some leisure moments.’ Renowned though Madeira may have been for its grapes, Dick was less than impressed by its melons: ‘Either from the little care that is taken in the raising them or from being chiefly of the large watery sorts, they are by no means superior nor indeed do I think them equal to many I have eat at T. Sowerby. I shall however send you some seed, especially of the Water Melon, which we have of an astonishing size.’[17]

On 4 November, the Atkinson family would be rocked by the death of Matthew, middle brother of George and Richard, the last male of the older generation. Bridget’s diary entry for this day reads simply: ‘My brother Matthew died at twelve minutes before nine in the morning.’[18] He left a widow and eight children, the eldest of whom was sixteen, the youngest less than a year old. Matthew’s demise cut both his and Bridget’s branches of the family adrift, for he had kept the Temple Sowerby banking business going since George’s death eight years earlier.

Matthew’s death was especially unsettling news for one of his nephews. Bridget had been nurturing hopes that her fourth son, Matt, would enter the family trade, which since 1778 had included responsibility for the collection of the land and excise taxes throughout Cumberland and Westmorland. But one of George and Matthew’s former associates, John Jackson, had recently started ‘Creeping into the Business’, having applied for the ‘Excise Money’, and was openly boasting of his determination to unseat the Atkinson family.[19] Matt, who was an affable but directionless young man of twenty, stood no chance in the face of such blatant ambition.

Bridget laid bare her distress in an anguished letter that she wrote to her son-in-law, Nathaniel Clayton, a few days before Matthew’s death. ‘All is I fear lost to my poor Boys,’ she lamented. ‘George says there is an opening for them at Jamaica I do not Look upon the West Indies to be a place at present to make a fortune or Mend the Morals of a young man it kills me to think of all my Boys going to Jamaica and where else can they go.’ Matt’s health was a particular cause for concern: ‘He has had a complaint in his Bowells for a Month past he is troubled with a Head ach which is at times very Bad and would render Jamaica dangerous and I think where he gos I will go for what comfort can I have when all my Sons are gone from me none here I am Sure my Heart is near Broke.’[20]

AS THE MURES’ financial problems deepened, their relations with the Atkinson family deteriorated. By their reckoning, Paul Benfield and their late partner’s estate jointly owed them at least £60,000 for the purchase of the Bogue estate – even though the property was worth £40,000 at most, as Robert Mure candidly admitted. During the autumn of 1789, the Mures spread the rumour that Benfield was on his way back from Madras to settle his debt with them, raising credit for their ailing house on the strength of this report; at the same time they threatened to have Benfield arrested for debt the moment he set foot on English soil.

By now, Benfield’s legal team were starting to wonder whether the Bogue purchase had been deliberately dreamt up as a scheme to defraud their client. Robert Mure’s multiple roles only thickened the fog that surrounded this ‘entangled, perplexed, & complicated’ business.[21] ‘He is one of the Persons who sold the Bogue to you & Atkinson,’ wrote Benfield’s advisor, Nathaniel Wraxall. ‘He is a Partner with Atkinson. He is an Executor to Atkinson’s Will. He is a Trustee to Atkinson’s Will; and He is, lastly, a Demandant for the Purchase Money due for the Bogue. How are we to negotiate with a Man in all these various, & discordant Capacities?’[22]

In March 1790, Benfield’s lawyers applied for an injunction that would prevent the Mures from harassing their client. Although not granted – on a technicality, for Benfield’s team were unable to subpoena Hutchison Mure, aged seventy-nine, on his sickbed in Suffolk – it was clear that the Mures could not afford to litigate, and would ‘sooner or later’ need to reach a compromise.[23] Now Benfield’s lawyers went on the offensive against the Atkinson estate. Clutching a letter in which Richard had once offered their client the option of relinquishing his share of the Bogue, they threatened the estate with a lawsuit to force the payment of £36,000 – half the sale price, plus accumulated costs – to take Benfield’s interest in the Jamaican property off his hands.

It was at this miserable juncture that Francis Baring, motivated by strong feelings of ‘friendship & regard’ for the Atkinson family, came to the rescue – negotiating with the Mures to buy out Benfield’s half share of the Bogue estate for £22,000.[24] Baring advanced them £6,000 of the money and Nathaniel Clayton the rest, which is how both men came to be creditors to Richard Atkinson’s estate.

THE SELECT COMMITTEE which had been set up after the first debates about the slave trade published its findings in early 1791, in three fat printed volumes. William Wilberforce planned to bring in a bill to ‘prevent the farther importation of Slaves into the British West Indies’ during the next session of parliament, but he realized that few MPs would care to wade through all 1,700 pages of the report, so he worked at full tilt to produce an abridged version that was ready just a few days ahead of the debate.[25]

Wilberforce opened the proceedings on 18 April, and spoke with supreme moral authority; the cross-party trinity of Pitt, Fox and Burke added their support. On the other hand, ‘tun-bellied Tommy’ Grosvenor, MP for Chester, conceded that the traffic in slaves ‘was not an amiable trade’, but pointed out that ‘neither was the trade of a butcher an amiable trade, and yet a mutton chop was, nevertheless, a very good thing’.[26] Alderman Brook Watson, representing the City of London, argued that ending the slave trade would not only ‘ruin the West Indies’, it would also destroy the nation’s Newfoundland fishery, ‘which the slaves in the West Indies supported, by consuming that part of the fish that was fit for no other consumption’.[27] Past three in the morning, after two long nights of debate, the House divided. The abolitionists suspected they would lose, but were unprepared for the scale of their defeat – 163 votes to 88.

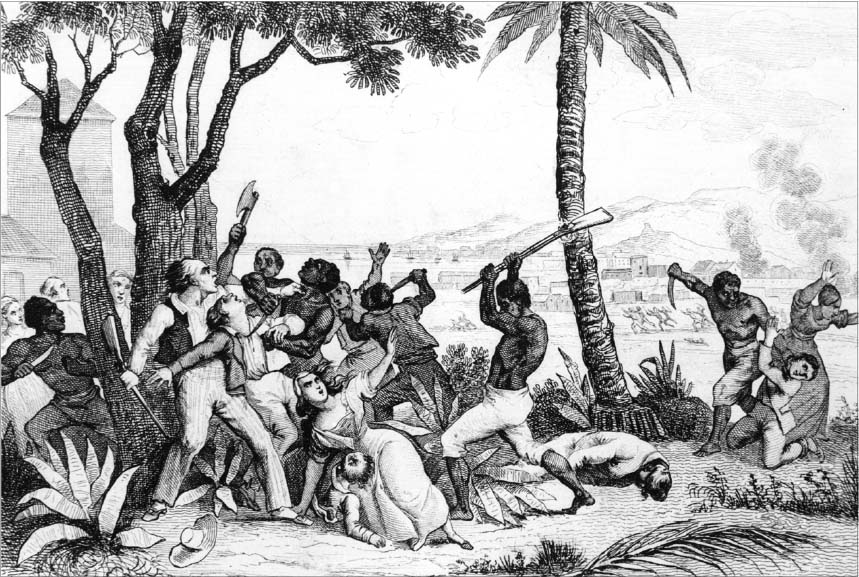

Vested interests had killed the slave trade bill. ‘Commerce chinked its purse,’ commented Horace Walpole, ‘and that sound is generally prevalent with the majority.’[28] But other factors had contributed to its trouncing – most specifically, violent uprisings in France and the West Indies. On 14 July 1789, a mob had stormed the Bastille fortress, a symbol of royal authority in the middle of Paris. That autumn, Thomas Clarkson had travelled to the French capital in order to forge links with abolitionists; by the time he returned to London, six months later, the intoxicated mood of liberté had fermented into something more frightening. The revolutionary fervour soon spread to the West Indies. In October 1790, Vincent Ogé, a mixed-race coffee merchant who Clarkson had met in Paris, led a rebellion in the French colony of Saint Domingue, demanding civil rights for his fellow ‘mulattoes’ – it would end with his execution on the breaking wheel in the square at Cap-Français. Then, in February 1791, news arrived in London of a slave insurrection on the British sugar island of Dominica; although quickly suppressed, it gravely injured Wilberforce’s embryonic bill.

The Comte de Mirabeau had memorably described the white population of Saint Domingue as sleeping ‘at the foot of Vesuvius’, and in August 1791 the volcano finally blew its top, as enslaved blacks from the Northern Province rose up in an orgy of arson and bloodshed. Soon, most of the plantations within fifty miles of Cap-Français had been reduced to ashes. Many of the grands blancs fled to nearby Jamaica, taking with them their most valued slaves and, as many British planters feared, the contagion of unrest. On 10 December, as rumours swirled round Jamaica of a secret society called ‘the Cat Club’, where enslaved men met to drink ‘King Wilberforce’s health out of a Cat’s skull by way of a cup’, General Williamson, the island’s governor, declared martial law.[29]

Racial violence erupts in Saint Domingue in August 1791.

Archives Charmet/Bridgeman Images

Following the defeat of the 1791 bill, abolitionists hit upon a novel way to show their disapproval. William Fox’s Address to the People of Great Britain, on the Propriety of Abstaining from West India Sugar and Rum suggested that all consumers of West Indian sugar had blood on their hands: ‘A family that uses only 5lb. of sugar per week, with the proportion of rum, will, by abstaining from the consumption 21 months, prevent the slavery or murder of one fellow-creature.’[30] Fox’s pamphlet ran to twenty-five editions, convincing thousands of ‘anti-saccharite’ families to boycott slave-produced sugar.

Ahead of the 1792 parliamentary session, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade set another petition campaign going. This time, unlike the spontaneous outbreak four years earlier, it would be a highly disciplined affair, with local committees receiving strict instructions to hold off from submitting their petitions until told to do so. (‘By no means let the People of Brough add their Names to those of Appleby,’ Clarkson cautioned his Penrith contact. ‘The two Petitions must be perfectly distinct. It is on the number of Petitions that the H. of Commons will count.’)[31] More than five hundred anti-slavery petitions, bearing half a million signatures, would arrive at Westminster that spring – at a time when the nation’s population was about eight million, and perhaps half the adults were illiterate, this was an incontrovertible expression of public feeling.

Even so, with lurid tales circulating of the slaughter of French planters in their beds, and the rape of their wives, the insurgency in Saint Domingue greatly damaged the abolitionist cause. Many sympathizers urged Wilberforce to pause for a while, but he chose to plough on regardless. On 2 April 1792, after a passionate speech to a packed Commons, Wilberforce moved that the slave trade should be abolished, and the debate was opened up to the floor. Late in the evening Henry Dundas, now Home Secretary, rose to speak. He had long shared Wilberforce’s views about the necessity of ending the slave trade, he declared – but he challenged the ‘prudence’ of an immediate abolition, instead proposing a ‘middle way of proceeding’ whereby the trade would be eliminated over the course of an unspecified number of years.[32] He then successfully moved for the word ‘gradually’ to be added to the original motion. At dawn the House of Commons overwhelmingly, by a margin of almost three to one, voted to ‘gradually’ abolish the slave trade.

This outcome left neither side satisfied. Wilberforce and his followers felt betrayed by Dundas. The pro-slavery lobby, suspecting that the motion would never have passed under its original wording, felt robbed of the chance to settle the question decisively. They need not have worried. The following month, the House of Lords rejected the bill, thereby stalling the abolitionist movement for fifteen years.

The Gradual Abolition of the Slave Trade, in which the royal family attempts to reduce its consumption of sugar ‘by Degrees’.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

AFTER BUYING OUT Benfield’s interest in the Bogue estate, Francis Baring and Nathaniel Clayton settled with the Mures that Bridget’s sons George and Dick would take possession of both their late uncle’s West Indian properties; at least now they would be able to prevent their inheritance from falling into ruin. George sailed to Jamaica in the autumn of 1791, landing at the bustling port of Lucea shortly before Christmas; twelve miles along a winding, dusty road, he was reunited with Dick, who had been learning how to be a sugar planter at the Mures’ Saxham estate. Samuel Mure (brother of Robert and William) relinquished his power of attorney over the Bogue and Dean’s Valley estates without fuss. A few days later, the Atkinson brothers rode thirty miles along the north coast of the island to the Bogue, where Dick would remain.

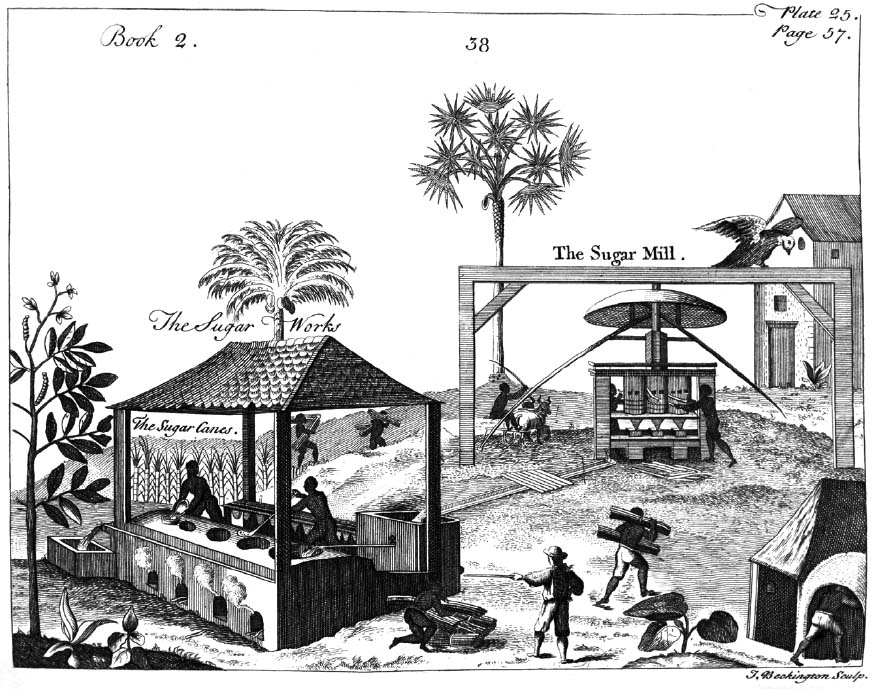

Two miles south of Montego Bay, the Bogue estate encompassed 1,300 acres bordering the emerald lagoon from which it took its name; this was the deceptively Arcadian setting for a factory complex operated by about two hundred enslaved Africans. Its infrastructure comprised a sugar works, including a cattle-powered mill, boiling and curing houses, distillery, stores and trash houses; offices for the (white) overseer and his deputies; workshops for the (enslaved) blacksmiths, carpenters, coopers, stonemasons and wheelwrights; a hospital for the sick and injured; a ‘great house’ for the proprietor; and a village of palm-thatched huts. The enslaved families also had access to plots where they grew the beans, cassava, maize, pumpkins and yams, and raised the poultry, goats and pigs, with which they supplemented the basic salt provisions supplied by the estate.

Sugar estates ran according to the principle of divide and rule, with rivalries among the enslaved population actively promoted by their white overlords. Members of the same family were separated; and a class hierarchy was imposed, whereby workers with white fathers or lighter skin were privileged over those with darker skin, and domestic servants, artisans and drivers had higher status than field workers. One of the first ‘skills’ that Dick would be expected to acquire, as a newly arrived sugar planter, was that of asserting his authority. ‘Men, from their first entrance into the West Indies, are taught to practice severities to the slaves,’ wrote an old Jamaica hand, ‘so that in time their hearts become callous to all tender feelings which soften and dignify our nature.’[33]

Grotesque evidence of this callousness is provided by Thomas Thistlewood’s diary. Born in Lincolnshire in 1721, Thistlewood was for many years the overseer on the Egypt estate in Westmoreland Parish. A keen botanist who exchanged tree and shrub specimens with the Mures at Saxham, he was also a sexual predator who logged 3,852 acts of congress with 138 women, and a sadist who enacted the cruellest of penalties for the pettiest of crimes. Notoriously, he devised ‘Derby’s dose’ to punish an enslaved boy who was caught eating sugar cane stalks; first the lad was flogged, then salt pickle, lime juice and chilli pepper were rubbed into his wounds, and finally another slave defecated into his mouth before he was gagged for several hours. Not surprisingly, the enslaved population continually showed signs of resistance, most frequently through minor acts of disobedience or running away, less often through assassination and violent rebellion; it was their fear of the latter, coupled with absolute impunity, that turned white men into despots.

At the end of each day, the tropical sun plunged into the sea on the horizon, and darkness fell within a few short minutes. While the fragrance of orange blossom drifted in the air, the tree frogs resumed their otherworldly nocturnal song and the fireflies shot ‘electric meteors from their eyes’, the white men amused themselves by drinking rum, playing cards, smoking cigars and raping the enslaved women.[34]

DICK’S ARRIVAL AT the Bogue coincided with the start of the harvest, or ‘crop’, as it was known. This was a noisy time of year, characterized by the ‘beating of the coppers, the clanking of the iron, the driving of the cogs, the wedging of the gudgeons, the repetition of the hammers, and the hooping of the casks’, as preparations were made for the intensive bout of sugar production ahead.[35] The cutting of the cane started after the Christmas holidays, when the enslaved workers were given three days off, and continued until the coming of the rains in April or May; for four months or so, the sugar works operated round the clock.

Cutting the cane – a tall reed with sharp, serrated leaves – was brutal work carried out by the physically toughest individuals, motivated by a driver cracking a whip. The moment the cane was cut, its juices started to ferment, and there was little time to lose; it was rapidly bundled on to waggons to be carted to the mill, which was positioned on a knoll above the rest of the sugar works. Here women pushed the canes, six or seven at a time, through three large hardwood rollers – forwards through the first and second, back through the second and third – to extract the cloudy, sweet liquor, which was channelled via a lead-lined gutter to the boiling house below. (A hatchet was kept close at hand, ready to amputate fingers caught in the rollers.) The cane trash was meanwhile collected up and kept as fuel. The women often sang while they worked. ‘It appears somewhat singular,’ observed one planter, ‘that all their tunes, if tunes they can be called, are of a plaintive cast.’[36]

In the boiling house, the cane juice was funnelled into an enormous cauldron, a small amount of lime added, and a fierce fire lit beneath. As the liquid heated, a raft of scum rose up; the flames were then doused, and the cauldron was left for an hour or so to let further impurities float to the surface. The clarified juice was next siphoned into the largest of a tapering sequence of about six copper pans; once boiled to nearly the ‘colour of Madeira wine’, the liquor was transferred to a slightly smaller copper set over a slightly hotter fire.[37] The cycle was repeated through to the final, smallest copper. When the liquor was thick and tacky, it was conveyed to a shallow wooden container about a foot deep and six feet square – the same volume as a hogshead barrel – to cool into an oozing mass of coarse crystals. Workers assigned to the boiling house had to remain on their mettle for the duration of their twelve-hour shifts – the slightest lapse of concentration might cause, at the very least, a disfiguring burn.

Afterwards the treacly sludge was carried in pails to the curing house, a large, airy building next to the boiling house, and poured into upright hogsheads balanced on joists above a large cistern. Over about three weeks, the molasses dripped through holes bored in the bottom of the barrels into the cistern below, leaving behind dark muscovado sugar in the barrel. The molasses were then taken to the distillery, where they were mixed with water, the juice of tainted canes, the skimmings from the boiling house coppers and the yeasty sediment from previous batches known as dunder; once fermented, the liquor was drawn off to be twice distilled, ending up as puncheons of potent Jamaica rum.

A highly simplified illustration of the process of making sugar.

AFTER DICK HAD SETTLED at the Bogue, George crossed the island to inspect their late uncle’s other property, fifteen miles to the south in Westmoreland Parish. Located on a wide flood plain, and sheltered by densely wooded hills, the Dean’s Valley Dry Works (to give the estate its full designation) was so called because it lacked access to the gushing spring that delivered power to the neighbouring Dean’s Valley Water Works, instead relying on ‘dry’ cattle to drive its cane mill.

George was pleased to see the sugar crop at Dean’s Valley looking ‘very promising’, but dismayed to learn that ten enslaved Africans had recently died there from fever; it seemed that the low-lying position of the estate hospital might be partly to blame. The great house, too, was so unhealthily situated, and in such a poor state of repair, that George wondered whether pulling it down and rebuilding it on the side of the hill might not be the best plan – for only then would he and Dick be able to stay for ‘two or three weeks at a time, which at present it would be madness to venture’. It was necessary, George told Francis Baring, that these visits should be regular: ‘The Negroes on both Estates are very deficient in that confidence and attachment which the residence of a Master alone inspires and which it will be our particular study to supply.’[38]

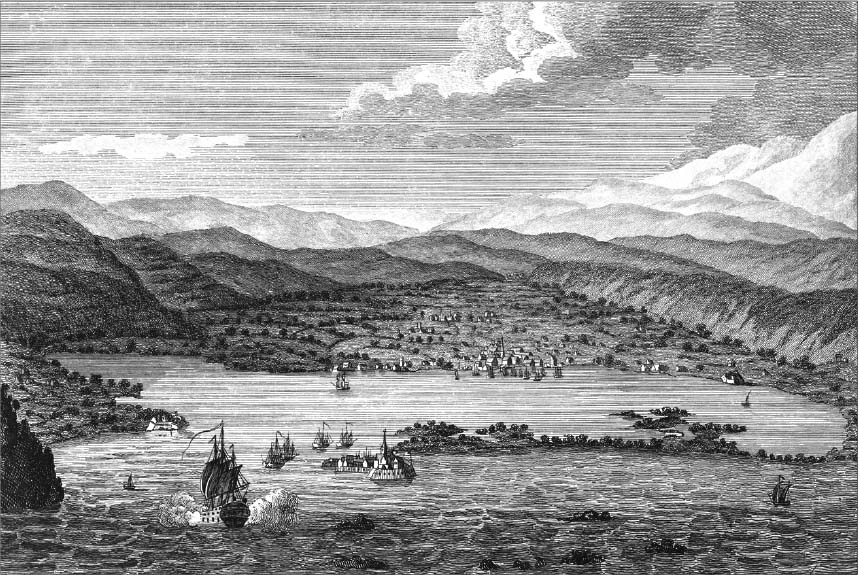

By February 1792, George was in Kingston, the commercial hub of the island. Worldly visitors, sailing into the town’s magnificent harbour and viewing the ‘sapphire haze’ of the Blue Mountains for the first time, sometimes fancied a resemblance to the Bay of Naples.[39] But the spell was broken the moment they stepped ashore; for Kingston’s charms were notoriously coarse, and centred around brothels, taverns and grog shops. In contrast the parish church, which lay a few blocks back from the wharves, was conspicuously neglected, moving one writer to comment: ‘It is a pity that the morals of the people are not corrected, so as to have it as much frequented by the living as the dead.’[40]

Kingston harbour, with Port Royal in the foreground, the Blue Mountains behind.

Wellcome Collection

Kingston’s merchants mostly lived on the outskirts of town, on higher ground, in residences with broad verandahs and shady balconies; driving downtown to their offices at about seven in the morning, they generally paused for a ‘second breakfast’ at noon, shutting up shop in time for dinner at four. The Jamaican merchant house of which Samuel Mure was a partner, Mures & Dunlop, was by now so caught up in the disorderly finances of the Fenchurch Street firm that George, sensing a trap, had wisely resisted the Mures’ attempts to have him join it; instead he would spend the next few months sounding out potential business partners on the island.

George was a restless young man, with a volatile temper and a burning desire to make some money of his own; without his own establishment, however, his hands were tied. ‘Opportunities have occurred since my arrival here by which had I been at liberty to have acted an ample fortune might have been realized without anything like comparative Risk,’ he told Baring on 11 June.[41] So he boarded a ship home in July, somewhat reluctantly leaving Dick (who had not taken to the sugar planter’s life) in charge of the family estates. ‘He one day talks of taking a trip to America, the next he means to return to England,’ George wrote about his brother. ‘One day he is to go home to marry Miss Howard, another that she is to come out to him next year, in short I don’t know what to make of him.’[42] As it happened, fate (arriving in a winged form) would soon swoop down and pluck the decision out of Dick’s hands.