SEVENTEEN

![]()

Black Pioneers

NATHANIEL CLAYTON purchased the Chesters estate in 1796 – his legal practice was flourishing. Some twenty miles west of Newcastle, as the crow flies, the mansion was a rather dour stone box of a building, but it commanded delightful views across open fields down to the banks of the North Tyne. Scattered round these meadows were the remnants of Cilurnum, a Roman cavalry station which had once guarded an important river crossing. Nathaniel immediately got started on improvements to the property, first diverting the public road running through the middle of its park, then tidying up the Roman rubble. ‘Large masses of ruins rising in heaps over a spacious field speak of former greatness,’ wrote a visitor in 1801. ‘The mutilated figure of a woman standing on the back of some animal has lately been dug up and is at present put in a wall enclosing a plantation; I should think it deserved a better situation.’[1]

Nathaniel soon proved himself a capable farmer. New field drains, dug at considerable expense, paid swift dividends. ‘My Neighbours begin to think that I am not such a Ninnyhammer as they first took me for,’ he told his youngest sister-in-law, Jane. ‘I am greatly bent on making two Blades of Grass grow where one only grew before.’[2] Across the country, a disastrous harvest in the summer of 1799 caused many poor families to go hungry the following winter; in Newcastle, a large soup kitchen was erected in the Poultry Market to feed those who were ‘ready to perish’.[3] Even that most basic of staples, peas, were hard to come by. ‘I imagine they must be very scarse,’ wrote Jane, who was staying with the Claytons at Westgate Street, ‘for at the Soup Kitchen they substitute Potatoes, which at present bear a very high price in proportion with every other kind of grain.’[4] With vegetables at such a premium, Nathaniel felt justifiably proud of his yield at Chesters. ‘My farming Skill has become notorious,’ he told his mother-in-law in February 1800, ‘for I had the best Crop of Turnips within 20 Miles of me, and Turnips were this year but another Name for Gold.’[5]

Ever since 1786, when he was hired by the Atkinson family to protect their inheritance, Nathaniel had worked tirelessly to promote the interests of his wife’s relatives. To give one minor example: in the spring of 1798, after reading in the Gentleman’s Magazine that a second cousin of the Atkinsons, a Miss Addison (daughter of Joseph Addison, the celebrated essayist and founder of the Spectator), had died intestate, Nathaniel made it his business to find out the value of her estate. ‘If I find the play worth the Candle,’ he told Jane, ‘I see a reasonable Ground to hope that I shall prove our Brother Michael entitled to the Property.’[6] But Nathaniel’s efforts to establish his brother-in-law’s claim as the old lady’s ‘laughing heir’ must have come to naught, for the subject was soon dropped.

The Clayton children often stayed with their grandmother and unmarried aunts at Temple Sowerby, and saw it as a second home; during the light summer months, it was possible to ride across the moors from Chesters in a single day. When they were seven, the boys were each in turn sent to board at the Rev. John Fisher’s school at Kirkoswald, ten miles from Temple Sowerby; having acquired groundings in Greek and Latin, as well as ‘broad Cumberland’ accents, they would go on to public schools in the south.[7]

Nat, the eldest, went to Harrow, and his letters to Bridget show him to have been a clever, amusing boy. During the Easter holidays of 1799, when he was eleven, he visited Parkinson’s Museum, which was housed in a rotunda on the south side of the Thames by Blackfriars Bridge. He reported back to his grandmother:

Among other curious things, we saw a piece of beef, which had gone round the world with Commodore Anson; also a great many Indian clubs, and a goat of Angora stuffed, all kinds of Butterflies and insects, and what amused Nurse most of all, a pair of Chinese woman’s shoes. In the second Gallery we saw a Chinese Pheasant, a blue bellied creeper, a Parrot, a swallow’s nest which was built in the wing of an owl, a bat, and a stuffed shark. As I know that you like long letters, and as I have nothing else to write about, I will proceed. I saw also a sea Hawk, a stuffed lap dog, a Tyger, a lion, a Buck, a Toucan, a scarlet humming Bird, a blue humming bird, a green humming bird, a Pelican, also silver and Iron ore, a stuffed ostrich, and a Cougar, a common hen and chickens with which Nurse was remarkably well pleased, a large collection of Shells, which she thought were Superior even to yours, the only specimen of the bread Fruit, which Captain Cook brought with him from the Island of Otaheite, a stuffed Cormorant, and a Crane.[8]

Little Bridget and John Clayton, aged nine and seven, spent the autumn months of 1799 at Temple Sowerby. They were engaging children, and their grandmother relished having them nearby as she knitted heroic quantities of woollen stockings for them and their siblings. ‘I am very glad that Mr. Clayton and you consent to Bridget and John’s staying a Little Longer with me who at present are in perfect good Health and are growing Stout and Strong for which I have to thank John Ching it has made such an alteration for the better,’ Bridget wrote to Dorothy on 27 October. (‘John Ching’ was a proprietary brand of worm lozenges – its principal ingredient being mercury.) ‘Bridget is fond of Patching and sits close by me and John plays at Cards by himself with the greatest good hummor and Dummy and he never disagrees.’[9]

FOLLOWING HIS RETURN to England, George Atkinson had spent a good deal of the autumn of 1798 on turnpikes, shuttling between family in the north and various ‘intricate unpleasant’ concerns demanding his attention down south.[10] The winding up of the house of Atkinson, Mure & Bogle was his first priority, with funds of almost £250,000 to be shared out between the three Kingston partners, as well as Sir Francis Baring, who had financed their business from London. Inevitably, some frank exchanges of opinion ensued. The Jamaican contingent argued that they deserved the lion’s share, since their possession of the Agent General’s office, through which the vast majority of the spoils had flowed, predated Baring’s formal connection with their business. Baring, on the other hand, reminded them that the Island Secretary was placed by virtue of his position in ‘so important, confidential a situation with the Governor’ that it almost always led to his appointment as Agent General – which was why, following the Mures’ bankruptcy, he had gone to the great trouble of renegotiating the lease on the Island Secretary’s office with its aristocratic owner, Charles Wyndham.[11]

George was unusually subdued during these discussions, perhaps on account of the dressing-down he had received from his patron that summer; certainly Baring noticed that he seemed ‘disposed to acquiesce with any terms we should propose’.[12] Once the Kingston partners had conceded the point over the Island Secretary’s office, Baring was generous in his settlement, accepting a lump sum of £70,000. His primary motive, he reminded his own partners, had always been to ‘reestablish & thereby serve the Atkinson family’.[13] Both sides signed the letter of agreement on 1 December 1798; and thus the books of the house of Atkinson, Mure & Bogle were closed.

The news of John’s death in Jamaica reached his mother and sisters at Temple Sowerby in late November. Although it must have caused them great anguish, their letters are entirely silent on the subject. Maybe the family gathered to mark John’s passing; George certainly travelled up to Westmorland in early December. As was the custom of the time, Bridget would wear black for the first year after her son’s death, moving on to muted colours for the second year. (On the first anniversary of Dick’s death, back in May 1794, Dorothy had written from Newcastle to tell Bridget that she had just dispatched a ‘french Grey callico gown for you of a sort much in use here for second mourning – also a very dark purple one for visiting the Hotbeds &c’.[14] I love the thought of Bridget pottering about the kitchen garden at Temple Sowerby, honouring her son’s memory as she tended her melon pit.)

Later that winter, in February 1799, George returned to London to make preparations for what he anticipated would be a ‘Hot Campaign’ at the Court of Chancery, where various of the Mures’ creditors were lining up to ‘commence Hostilities’ against his uncle’s estate.[15] ‘Their Claims are immoderate and very extraordinary,’ George wrote to Lord Balcarres. ‘Upon the whole I apprehend I shall have very ample Employment in the Liquidation of these Concerns for many months. I have abandoned all Hopes of returning to Jamaica this Season.’[16]

WITHIN DAYS OF his brother John’s death, Matt Atkinson was sworn in as Island Secretary of Jamaica; the family’s affairs in the colony now rested on the shoulders of its laziest member. Shortly after Christmas, Matt slipped away from Kingston to inspect the estates at the west end of the island. ‘The Bogue is coming round fast I expect 200 Hhds this Crop,’ he told Baring on 10 February 1799. ‘There wants a great deal to be done at Deans Valley, both as to establishing Guinea Grass, draining Land, and putting on Negroes, before the Estate can be brought to what it ought to make, which is 280 to 300 Hhds.’[17] Following years of underinvestment, parts of Dean’s Valley were on the point of collapse, with urgent repairs needed to the sugar works, overseer’s house and other buildings – a local surveyor estimated that ‘it would require 40,000 Shingles and 10,000 feet of Boards to do what is Absolutely necessary’.[18] On both estates, the workforces were ‘much upon the decline’.[19] Over three years – from the beginning of 1797 to the end of 1799 – the enslaved population at the Bogue would fall by fifteen, to 215 (seven births, minus twenty-two deaths), while at Dean’s Valley it would fall by thirteen, to 208 (twelve births, minus twenty-five deaths).[20]

In London, George set up a new merchant house, to be known as G. & M. Atkinson. He would look after its interests in England, while three partners – brother Matt, John Hanbury and Hugh Cathcart – would manage its operations in Jamaica. ‘I think it is time that we should begin a private correspondence,’ Baring wrote to Matt on 12 August – by which he meant a frank correspondence, transcending the platitudes of the monthly letters between the two houses. Baring had been speaking to John Wigglesworth, the former commissary in Saint Domingue, who had told him that Matt could not decide whether to focus on the sugar plantations or on the mercantile branch of the business. Baring strongly urged Matt in the latter direction: ‘In my opinion there can be no doubt under the present circumstances, for you cannot make your Counting house too strong whilst such various & important commercial objects are passing before you.’[21]

During the autumn of 1799, a transaction took place concerning the ownership of the two Jamaican estates; insignificant though it might seem, it would subsequently cause a great rupture in the Atkinson family. Now that he was rich in his own right, George agreed to buy out the interests in the Bogue and Dean’s Valley estates which Nathaniel had some years earlier acquired from Paul Benfield and Captain Laird. On 6 December, Nathaniel and George visited Baring at his mansion near Lewisham. ‘I have the Satisfaction to tell thee that we yesterday closed our accounts; visiting Sir Francis at Lee for that Purpose,’ Nathaniel later wrote to Dorothy. ‘They met with his entire approbation & after they were examined & closed he turned to George & thus expressed himself (forgive, my dear Girl, my Vanity) “George I want Power to express how much the Atkinson family & you in particular, are indebted to Mr. Clayton: It is impossible that they or you can ever forget it.” This as thou wilt readily believe was very grateful to thine ever, N.C.’[22]

SUCH WAS THE mortality rate that military service in the West Indies was seen as more or less a death sentence for white rank and file; and yet, whenever the British authorities proposed drafting enslaved Africans, the planters made clear their aversion to the idea of ‘slaves in red coats’. But the mobilization of a large black army in Saint Domingue had increased pressure to boost the sugar islands’ defences; which is why, in 1795, Henry Dundas ordered the formation of eight regiments made up of Africans discreetly purchased by the government. (The discretion being necessary to avoid embarrassing ministers who publicly backed abolition.) The First West India Regiment, which assembled in the Windward Islands, acquitted itself with great credit; but when Lord Balcarres attempted to raise a West India Regiment to serve in Jamaica, the House of Assembly blocked him from doing so.

If the idea of placing weapons in the hands of black men made these powerful white men shudder, they unquestioningly accepted the use of black ‘pioneers’. These were the labourers who performed the drudgework of military life; armed with pickaxes, saws and shovels, they built fortifications, dug trenches, hauled ordnance and provisions, and generally carried out the most backbreaking tasks. Two pioneers were attached to each of the fifty-six companies garrisoned in Jamaica, although Balcarres hoped to increase this number to six. For the past fifteen years, the island’s pioneers had been largely composed of free blacks who had emigrated from Georgia following the American revolution; but most of them were now either exhausted or dead. To fill the gaps, the army had been hiring enslaved men for up to 5s each per day, saddling the island with an annual bill of more than £20,000 currency. In November 1797, the House of Assembly passed a resolution approving the governor’s proposal to place the pioneers on a cheaper footing.

Lord Balcarres’ plan involved putting the contract to supply pioneers out to public tender. The government would offer to pay £15 currency for the annual hire of each enslaved pioneer, plus an annual clothing allowance of 46s, and a day rate of 8½d – such terms, Balcarres assured the Duke of Portland, would not only prove less expensive for the island, but would furnish a ‘very good Return indeed to any Contractor who may chuse to speculate’ – and yet, a year after the Assembly passed its resolution, not one merchant in Jamaica had expressed interest in taking on the business.[23] Baffled by the failure of his scheme, Balcarres consulted ‘some of the first Merchants in Kingston’, who told him they believed that military service would make enslaved men unfit for other forms of work.[24] At last, though, a willing merchant was found. On 24 August 1799, the contract with Balcarres, who was acting ‘on behalf of the British government’ – at least, that is how the official paperwork defines his role in the transaction – was signed by Matt Atkinson. The house of G. & M. Atkinson would supply ‘so many able negro men as Pioneers for the several white Regiments of Cavalry or Infantry’ stationed on the island, ‘at the rate of 6 Pioneers per Troop or Company’; a year’s notice was needed to terminate the agreement, following which such pioneers ‘as shall not be dead or runaway’ would be returned to the contractors in Kingston.[25]

This was a corrupt, self-serving business, and not just for the obvious reasons – for, secretly, in collusion with Matt Atkinson’s firm, Balcarres had taken a one-third stake in the pioneer deal, which made him a party to both sides of the negotiations. At the beginning of 1801, eighteen months into the contract, the Kingston house (and their silent partner) would have 357 pioneers on hire to the British army.

From the very start of my investigations into my ancestors, I knew that I was bound to unearth some unpalatable details of their slave-owning activities, and as the grim revelations piled up, my sorrow and regret about this aspect of their lives increased. By the time I came upon the pioneer contract, in the archive of the National Army Museum, I was quite far along with my research, and thought I had seen it all. But this discovery exposed a new dimension to my ancestors’ participation in slavery, one I hadn’t anticipated. Not only had they possessed hundreds of enslaved Africans on their estates; they had also acted, to a perhaps unique extent, as suppliers of slave labour to the British armed forces.

IN JULY 1798, the United States suspended trade with France and its colonies in retaliation for privateer attacks on American merchant shipping; the embargo caused great hardship in Saint Domingue, which relied on the mainland for much of its food. However, both Britain and the US wished to maintain a friendly dialogue with the black general Toussaint Louverture, so as to deter the ‘dissemination of dangerous principles among the slaves of their respective countries’.[26] In May 1799, Brigadier Thomas Maitland, who had overseen the British withdrawal from Saint Domingue the previous year, returned there with a mandate to make a treaty with Toussaint on behalf of both nations; the ports of Port-au-Prince and Cap-Français, it was agreed, would be opened up to trade. Subsequently, Lord Balcarres prevailed on Hugh Cathcart and Charles Douglas ‘of Mr. Atkinson’s Office’ to act as resident agents in the two towns.[27]

General Toussaint Louverture.

The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Toussaint had hoped to keep the treaty a secret, but his arch-rival, the ‘mulatto’ general André Rigaud, soon came to hear of it. The feud between the men had been simmering for a while, but Toussaint’s Anglo-American convention provided Rigaud with the casus belli for the vicious power struggle that would become known as the War of Knives. ‘Rigaud is already in motion, and has put to death a very considerable number of the White Inhabitants both at Jeremie and aux Cayes,’ Maitland briefed Balcarres on 20 June. ‘I find Toussaint is in very great want indeed of Provisions so much so that his Troops are at a stand for want of them.’[28] Matt Atkinson duly arranged for ‘two thousand Barrels of Flour, fifty Barrels of Salt Fish, two hundred Barrels of herrings, one hundred Barrels of salt Beef, fifty Barrels of salt Pork, three hundred Barrels of Biscuit’ and ‘ten Hogsheads of Tobacco’, along with arms, ammunition and gunpowder, to be loaded on to three ships that sailed to Port-au-Prince three weeks later.[29]

Meanwhile the French Republic’s agent on Saint Domingue, Philippe Roume, was working on a plan to undermine its British neighbour. The merchants Isaac Sasportas and Barthélémy Dubuisson arrived in Jamaica in early November 1799, with orders to spy on the island’s defences and incite rebellion among the enslaved population; General Toussaint’s army would then mount an invasion during the Christmas holidays. But Sasportas and Dubuisson were arrested soon after reaching Kingston – and their betrayer was none other than Toussaint, who had detected in Roume’s plot the motive of driving a wedge between him and his British backers. Shortly afterwards, Lord Balcarres received a shopping list of armaments urgently required by Toussaint, which included 6,000 muskets, 2,000 pairs of pistols, 30,000 pounds of lead and 100,000 pounds of gunpowder. The British agent in Port-au-Prince, Hugh Cathcart – a partner of the house of G. & M. Atkinson – was summoned for regular meetings with Toussaint about these supplies. ‘I have been with him almost daily for these last three weeks (& have become an immense favourite),’ Cathcart wrote on 26 November. ‘He has pressed me very hard, lately, to buy him a Frigate, and seemed rather dissatisfied, at my not complying with his request – altho’ I assured him that it was totally out of my power. He then asked me, if that I thought Lord Balcarres, would procure him one.’[30]

After the discovery of the French plot, the conspirator Dubuisson escaped the noose by confessing to everything; but Sasportas was hanged from gallows thirty feet above Kingston parade ground, wearing a label that spelled out the word ‘SPY’ in large letters.[31] Lord Balcarres – whose fate was to have been poisoning ‘by an infusion’ into his coffee on the morning of 26 December – declared martial law, and ordered ‘every French male Person of Color above the age of 12’ to be shipped off the island.[32] The house of G. & M. Atkinson made the necessary arrangements for the deportation of nearly one thousand men to Martinique and Trinidad.

Toussaint’s relations with the British cooled in December 1799, however, when four of his armed ships were seized mistakenly by the Royal Navy and condemned as prizes by the Court of Admiralty. Despite warnings that Toussaint would become a ‘most implacable enemy’, Sir Hyde Parker, the naval commander in Jamaica, stood firm in his opposition to the vessels’ return.[33] Following the theft of his ships, Toussaint was in no hurry to honour debts to British merchants, and so Cathcart – who had sold supplies to the general on credit, and invested £80,000 of his partners’ silver in coffee and other produce on Saint Domingue – was forced to linger at Port-au-Prince, pressing for payment and praying that the partnership’s goods would not be impounded. Finally, after an impasse lasting several tense months, Cathcart could return to Kingston with good news. ‘I feel well pleased to have it in my power to be able to say to you that I have received full payment from the Black General,’ he wrote to George Atkinson on 12 June. ‘We are now fairly out of the scrape and I trust we shall never again get ourselves into such another. Every thing is brought off excepting about Forty Bales of Cotton, for which I could not find freight, but I look for them in a Vessel that is daily expected.’[34]

SAINT DOMINGUE HAD ENTERED the 1790s as the richest colony in the West Indies, but its productivity plummeted as it was engulfed by conflict. In marked contrast, this was a buoyant decade for Jamaica. The wholesale price of sugar almost doubled on the back of Saint Domingue’s misfortunes, and the proprietors of estates returned to cultivation land previously given up as exhausted. During this decade, most Jamaican planters abandoned the old ‘Creole’ sugar cane, brought to Hispaniola by Columbus in 1493, in favour of the ‘Otaheite’ variety, introduced from the South Seas by Captain Bligh in 1793. This succulent newcomer was taller than its predecessor, tolerated poor soil, and yielded up to a third more sugar. Jamaican sugar, long regarded as overpriced, enjoyed strong demand in continental Europe.

But it all came to a juddering halt in 1799. The collapse started in the German port of Hamburg, home to more than three hundred sugar refineries, the highest concentration in Europe. The Jamaican merchant fleet arrived there later than usual that spring and was unable to offload its cargo; an American fleet carrying Cuban sugar had docked first and flooded the market. ‘The total Stagnation in the sale of West India produce has occasioned such distress as cannot be described,’ Baring wrote to the Kingston partners on 5 October 1799. ‘Above forty houses, some of these considerable, have failed at Hamburg & we expect to hear of more on the arrival of every mail; about Ten houses have failed here.’[35] By the end of the year, the warehouses along the River Thames were clogged up with tens of thousands of unsold hogsheads of muscovado.

During the boom years of the 1790s, the Jamaican planters’ hunger for fresh supplies of slave labour had reached frenzied levels, building to a peak at the end of the century. In 1800, more than 22,000 African men, women and children would land at Jamaica on board sixty-five slave ships – this would be the second highest year of arrivals on the island. The house of G. & M. Atkinson handled the sale of six of these human cargoes, comprising 2,350 people; so while it might be observed that the Kingston partners were latecomers to this line of trade, they nevertheless embraced it fully.

Usually, a slave shipowner made arrangements with a Jamaican merchant house for the sale of its human cargo at the start of a triangular voyage; but sometimes the ship’s captain would complete the middle passage, then assign the business on the spot. Either way, the Kingston merchant handled the money side of the sale, advancing bills drawn on its corresponding London merchant house (Barings, in the case of G. & M. Atkinson) to pay the shipowner for the cargo, extending credit to planters buying the enslaved Africans, and securing guarantees from those planters to sell their produce through the London house. This despicable business was replete with financial hazard from beginning to end – especially so for the London merchant house, which depended upon the planters sending back produce of sufficient value to pay for the slaves they had recently purchased. At a time when the price of sugar was in freefall, the speculations of G. & M. Atkinson placed Barings in a dangerously exposed position.

The Kingston partners were preparing to sell off their first cargo – 275 Africans who had arrived on board the Mary – when they received Sir Francis Baring’s gloomy letter about the collapse of the sugar market.[36] Clearly it didn’t faze them too much. ‘We have been induced to take up another Guineaman called the Will with 405 Eboe Negroes, the sales of which we have effected without even the expence of advertising, at an average of £75 Stg principally to people of this Town,’ wrote John Hanbury, the partner driving the business, on 23 March 1800.[37] Baring’s reply, warning that planters who purchased Africans on long credit might not be able to pay for them, given the current ‘low prices of produce’, crossed with Hanbury’s subsequent letter, which notified him that G. & M. Atkinson had taken up ships called the Sarah and the Young William, and also, by prior agreement, guaranteed two cargoes from the Liverpool slave traders J. & H. Clarke.[38]

In his next letter to Jamaica, dated 8 August, Baring made plain his displeasure: ‘If you carry on every branch of your business on a presumption that I am able to answer such boundless demands I must inform you very distinctly that my capacity nor my disposition are not equal to your expectations.’[39] George Atkinson further warned his partners: ‘On your Guinea Concerns I have only to repeat my former Caution, that you carefully avoid any Connection which can involve you deeply with the Soil of the Island. Credits to Planters are at all Times dangerous; but just now most eminently so – for be assured a Storm hangs over our Island, the bursting of which we must guard against by every possible Precaution.’[40]

So great was Baring’s alarm that he urgently called George down from Newcastle for a meeting with himself and George Bogle, who had held on to a stake in the Kingston house since retiring. Despite his poor health (three years earlier, a lead ball had lodged in his thigh during a naval engagement off Martinique, causing him constant pain), Bogle agreed to go out to Jamaica to apply some discipline to the operation. He wrote to Baring on 2 January 1801, four days after landing at Kingston; although he was not yet able to judge the conduct of the individual partners, it seemed that ‘from an apprehension of the War not lasting long’, they had thrown themselves headlong into the slave factorage business, ‘tempted by the appearance of great profit but without recollecting that they were thereby leading you into tremendous advances’. So as to disguise the real reason for his ‘sudden appearance’ in Jamaica, he had ordered a notice to be placed in the local newspapers, announcing the firm’s name ‘being changed to Atkinsons Hanbury & Co’.[41]

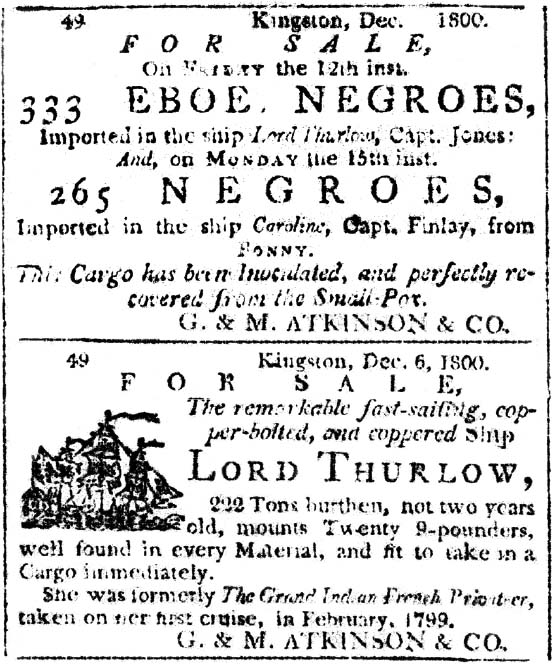

G. & M. Atkinson’s advertisement for two human cargoes, placed in the Jamaica Gazette of December 1800.

National Library of Jamaica

Three weeks later, Bogle was ready to offer a fuller analysis. It seemed that the late John Atkinson, during his brief stint at the helm, had ‘constantly resisted’ more hazardous lines of business. The problems had started after his death, with the establishment of G. & M. Atkinson. Instead of setting up a system by which each partner took responsibility for a branch of the business, everything had fallen upon the most experienced partner, John Hanbury – and thus, while it would be fair to say that Matt Atkinson had ‘cordially acquiesced’ in these speculations, Hanbury had been the ‘principal mover’ behind them.[42] Matt wrote privately to Baring on 28 January, expressing his ‘astonishment and shagrin’ at what had gone on; he had been quite genuinely under the impression that all was going swimmingly.[43]

LORD BALCARRES’ devil-may-care style of governance earned him the gratitude of the island plantocracy – ‘perhaps the assembly of Jamaica never agreed more perfectly and uniformly with any governor than it did with the Earl of Balcarras’, a contemporary would write – but he was viewed by his ministerial superiors as a maverick and a liability.[44] In the autumn of 1800, General John Knox was appointed to replace him as governor, but drowned during a hurricane on his way out to Jamaica.

When Balcarres learnt that he was about to be recalled, he set aside his public duties and focused on putting his personal affairs in order. During the six years of his governorship he had made plenty of money – much of it through negotiating government bills for the subsistence of émigrés from Saint Domingue – and had ploughed it into coffee estates in the parishes of St George and St Elizabeth that were said to be worth ‘not less than £60 or £70,000’.[45] As the time of his departure neared, Balcarres’ neglect of his official workload increased. ‘Our Governor is a strange Man,’ George Bogle wrote on 20 June 1801. ‘He has been living secluded at his Mountain in St. Georges for a Month past and although the Packet has been arrived these three weeks, he only returned to the Kings House yesterday to open his Letters.’[46]

Before Bogle returned to England, he composed a memorandum assigning clear duties to each of the Kingston partners:

The Business of the Agent General, and Settlement of accounts with the Governor, to be under the immediate management of Mr. Hanbury, also the correspondence with the House in London … Mr. Atkinson will conduct the Island Correspondence, with that concerning the Consignments from Ireland &c. – also the Correspondence with Head Quarters … Mr. Atkinson will likewise take upon himself the superintendance of the Sales of produce; and I particularly recommend to him to peruse in the Day Book every morning, the Transactions that have taken place in the preceding day. The Partners should be in the Office from Eight in the morning until Four in the afternoon. Indeed in this climate going out of Doors should as much as possible be avoided, for a person cannot again that day set down to business in a collected manner.[47]

On 23 July, Bogle boarded the Lowestoffe; strong currents, however, drove the ship aground soon afterwards in the Caicos Passage. Bogle returned to Jamaica, and there he would remain for the rest of the year, until the risk from hurricanes had abated.

The arrival at Port Royal on 29 July of the new governor of Jamaica, General George Nugent, was marked with gunfire ‘so stunning’ that his wife hid in her cabin on board the Ambuscade, holding a pillow over her ears.[48] Maria Nugent would cut a glamorous figure in Jamaica, for ladies of rank were a rarity out there – and Mrs Nugent was a small, neat woman, with a reputation as an ‘amazing dresser’ who never appeared ‘twice in the same gown’.[49] More significantly, she was a sharp-eyed diarist, who left behind easily the most vivid account of life on the island during the first decade of the nineteenth century.

Some of her first observations relate to the filthy state in which she found the King’s House, and the poor personal hygiene of the outgoing governor. ‘I wish Lord B. would wash his hands, and use a nail-brush, for the black edges of his nails really make me sick,’ she wrote after breakfast on her second morning. ‘He has, besides, an extraordinary propensity to dip his fingers into every dish. Yesterday he absolutely helped himself to some fricassée with his dirty finger and thumb.’ She was grudgingly amused, however, by an ‘extraordinary pet’ that patrolled the dining room – a ‘little black pig, that goes grunting about to every one for a tit-bit’.[50]

Before Lord Balcarres’ departure from the island, in November, he signed the power of attorney that passed responsibility for his estates to Matt Atkinson. Martin’s Hill, Balcarres’ coffee estate and cattle ranch in St Elizabeth Parish, became a favourite staging post for Matt during his journeys to the west of the island. ‘I have built a room off the North end of the House at Martins Hill and have sent a Bed there for myself,’ he would tell Balcarres.[51] Matt particularly appreciated the hospitality laid on by Robert White, the estate’s overseer: ‘I had as good corned Pork, and poultry, as any man would wish, and he has now got into a stock of good Old Rum. I call this very excellent plantation fare.’[52]

Lord Balcarres had gone out to Jamaica with a view to replenishing his family’s coffers, and his governorship had certainly served the purpose – even if most of his newly acquired fortune was tied up in West Indian property. The Countess of Balcarres, who had not seen her husband in nearly seven years, wrote to him from Edinburgh on 4 January 1802, ahead of his ship’s return: ‘I hope this will greet you on your arrival in perfect health & spirits, after all the toils & dangers you have so long encountered. No man can shew his face to the world with a better grace, or a sounder mind, than you can, & I am much prouder to congratulate you on that, with the very moderate sum you bring home – than what you might have made, with the smallest reflection on your conduct.’[53]