TWENTY

![]()

Settling Scores

FOR THIRTY YEARS, Richard Atkinson’s executors had ridden roughshod over the claims of Lady Anne Barnard; so when the last of them, Robert Mure, died in January 1815, her lawyers saw a chance to step into the breach. Michael Atkinson, motivated by his deep sense of grievance against Nathaniel Clayton, decided to join Anne’s cause, and together this unlikely pair filed a petition for the Letters of Administration that would grant them control of the estate’s assets.

But they had not reckoned on the opposition of Richard’s nine nieces. Like Anne, these middle-aged women had been left annuities of which they had not received a penny; more significantly, though, they were the ‘residuary legatees’ of their uncle’s estate. While planning his will, Richard had been so wildly optimistic in his financial projections that he had envisaged the profits from his Jamaican plantations accumulating into a fund from which all the annuity payments would be paid, and from the residue of which his nieces would each receive a lump sum of £4,000. This placed them next in line to take over the administration of the estate; Jane volunteered to represent her sisters and cousins in court, and Nathaniel dealt with the necessary paperwork.

When Michael learnt that his female relatives had shown the temerity to place their own interests ahead of his, he fired off a letter to Jane – ‘short and very very tart’ – conveying his ill feelings. She was in Newcastle at the time, and she instantly warned cousin Matthew Atkinson, who lived across the village from her at Temple Sowerby, about some petty ways in which her brother’s displeasure might soon make itself manifest: ‘I expect Michael will be writing to you probably to take immediate possession of the Moss field.’ (This was part of the small farm left him by their mother.) ‘There is a large Compost Heap which at all events I would be obliged by your telling Isaac to remove immediately & any thing that you may observe that might be claimed.’[1]

The Prerogative Court of Canterbury sat in June 1815 to weigh up the rival petitions for the administration of the Atkinson estate. As Jane predicted, the ‘spirit to pursue Mr. Clayton’ gripped Michael in the courtroom, and his evidence spewed forth as a litany of bitter accusations.[2] Whether Michael’s animosity influenced the judgement is not clear, but Sir John Nicholl brushed aside both Lady Anne Barnard’s claim as an annuitant and Michael’s as a legatee. ‘It is objected that Mrs. Jane Atkinson resides at a distance, and is a spinster: but really these objections are ludicrous,’ he pronounced.[3] As a residuary legatee – even when there was no prospect of inheriting any residue – the youngest sister’s claim took legal precedence over that of the eldest brother.

BY ANY STANDARDS, Lady Anne Barnard had lived an eventful life – from mixing with royalty and statesmen to clambering up Table Mountain – but these days she barely left her house in Berkeley Square. Her late husband, who had remained in the Cape Colony after she returned to England in 1802, had posthumously sprung a surprise upon her – for no sooner had she received word of his death out there in 1807, than another letter arrived informing her that he had fathered a daughter by an enslaved woman. Anne saw it as her duty, a ‘debt of honour’ even, to care for the child, as the ‘accident of an unguarded moment’ after she had left her ‘poor husband a lonely widower’.[4] Christina Douglas, this ‘dear little girl of colour’, went to live with her adoptive mother in London during the summer of 1809, when she was six.[5]

The other great love of Anne’s life, her sister Margaret, died in December 1814. Following Alexander Fordyce’s death in 1789, when she was thirty-six, Margaret had lived on and off with Anne in Berkeley Square, before ultimately enjoying two blissful years of marriage to Sir James Burges, a longstanding admirer. Anne had spent much of 1815 mourning the loss of her sister; but the first day of the following year found her in resolute frame of mind, as she sat down to draft an eighteen-page memorandum addressed to her heirs: ‘A Hasty Sketch of Particulars respecting my Acquaintance with Richard Atkinson Esq. and his management of my affairs – For the Information of those who may one day have an Interest in them’. She meant by this a financial interest – for she was considering how best to pass her claims on the Atkinson estate down to the next generation, having accepted that she was ‘too old’ to pursue further litigation.[6] ‘With a nest of young Attorneys, Claytons & Atkinsons on the Estates, living like princes, war is better than peace, at least to the Clayton folks,’ she observed to her brother, Lord Balcarres, on 24 March 1816.[7]

By now, Anne was immersed in a major literary project – she was writing her autobiography. For several years she would labour away on this magnum opus in her forty-foot drawing room at Berkeley Square, under the watchful eyes of her beloved sister, as portrayed by Thomas Gainsborough, surrounded by ghosts and papers from her past. Inevitably, what she had once envisaged as a ‘sketch’ of her life expanded into a sprawling narrative.[8] As her health and her handwriting deteriorated, she increasingly relied upon Christina, her ‘young amanuensis’, whose careful script would end up filling the pages of six volumes.[9]

Anne’s lively, candid memoirs caused a good deal of disquiet within the Lindsay family. Her siblings – particularly the decorous Countess of Hardwicke – feared she would unburden herself of secrets that would bring discredit upon them all. Anne calmed their nerves by giving ‘feigned names’ to her ‘real characters’, including herself, and thus the manuscript acquired the title The History of the Family of St Aubin and the Memoirs of Louisa Melford. (Richard Atkinson became ‘Robert Williamson’.)[10] She also decreed that the work could never, ever be published: ‘I utterly debar it.’[11]

FOLLOWING THE ABDICATION of Napoleon Bonaparte from the French imperial throne in April 1814, the triumphant allies – Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia – assembled in Paris to negotiate a treaty to restore peace to the ravaged continent. Ever since Admiral Nelson’s victory off Cape Trafalgar in October 1805, which had secured Britain’s maritime supremacy, the Royal Navy had kept French trade in check; but now, at the peace talks, it was suggested that France might be allowed a five-year revival of the slave trade, so its planters could put their West Indian possessions back in order. There was no mistaking the reaction of the British public to this regressive proposal. Thomas Clarkson, the veteran activist and chairman of the African Institution, called for petitions to be fired at Westminster from every corner of the country; by the time parliament rose for the summer recess, on 30 July 1814, more than eight hundred petitions had already been delivered.

In the British West Indies, as abolitionists had always predicted, the enslaved workforce dwindled without regular cargoes from Africa. In March 1810, two years after the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act came into force, the Kingston house of Atkinson, Bogle & Co. had told Lord Balcarres that they were finding it ‘exceedingly difficult to obtain singly, prime Negroes of either Sex’, and the supply had shrunk further since then.[12] ‘The Sum of my Inclination as to my Jamaica Properties is this,’ Balcarres had written to the house, in clear frustration, three years later: ‘I do not want Money – I want Negroes.’[13] But a proportion of the slave trade still carried on underground, and it was to smother this business that William Wilberforce tabled a parliamentary motion, in June 1815, to make the registration of slaves compulsory. Not only would the name, age and sex of every enslaved person be recorded; any changes to their status due to their sale, escape, manumission, or death, would also be logged. By keeping much stricter tabs on the numbers and movements of the enslaved population, it would be far harder for slave owners to conceal instances of illegal trafficking.

So outraged were West Indian planters at this attempt by Wilberforce’s ‘party of fanatical bigots’ to meddle in their internal affairs, however, that the Westminster bill was withdrawn; instead the separate island assemblies were persuaded to enact the legislation at a local level.[14] The House of Assembly in Jamaica would pass its registration bill in December 1816. Prior to registration, most anti-slavery campaigners had known little about the people in whose welfare they took such interest; but the new law meant that slave owners could no longer treat their human property as an abstract mass. From now on, the enslaved population would be composed of counted, named individuals.

During this time the Kingston house was in a state of flux. After George Atkinson’s death, Edward Adams and Robert Robertson had returned to England to wind up their late partner’s affairs, bringing (it was said) some £300,000 with them. Subsequently, in an alliance which raised eyebrows within the wider family – certainly it was ‘not impeded by any antediluvian Notions of Coyness & Reserve’, remarked Nathaniel Clayton – Robertson, who was thirty-eight, had married Bridget Atkinson, George’s sixteen-year-old daughter.[15] Meanwhile out in Jamaica, George Clayton, second son of Dorothy and Nathaniel, had died of a fever in April 1816 at the age of twenty-six.

It was the responsibility of the Kingston house, as Lord Balcarres’ attorneys on the island, to file his first slave return. But there was a catch – for the registration process threatened to expose, after eighteen years’ concealment, the corruption that lay at the heart of the pioneer contract, whereby the former governor had secretly signed up for a one-third share of the business of supplying ‘black pioneers’ to the army. ‘I do not perceive any Means of omitting your Lordship’s name in the Return,’ warned Edward Adams in February 1817.[16]

Adams wrote to Balcarres again in August, this time to tell him about a letter written by a junior minister which suggested that the pioneer contract should be ended immediately: ‘It also mentions Lord Balcarres’ Interest, and insinuates the Contract to have been a Job.’[17] The degree to which Balcarres was spooked by this message is plain from the many scrawled sheets of foolscap, scarred with crossings-out, in which he fabricated a story that would clear him of wrongdoing. ‘I think I have made out a strong case,’ he told Adams. ‘I deny the Job & deny that I am the holder of the share.’[18] Adams counselled Balcarres to keep quiet. ‘The Paragraph I quoted to your Lordship is information collected quite privately,’ he wrote. ‘We could give no reason for imputing to ministers, therefore, a suspicion of the Contract being underhanded. Consequently, an attempt to justify it would appear like being betrayed by a guilty conscience.’[19] This was sound advice, for neither was the pioneer contract terminated, and nor did any investigation come about. By November, moreover, Adams was able to pass Balcarres some ‘satisfactory Intelligence’ from Jamaica.[20] The pioneers had been registered by the commanding officers of the regiments they served, and not by the Kingston house; and thus his Lordship’s good name remained unsullied.

THE ANTI-SLAVERY MOVEMENT had deep roots within Nonconformist Christianity; the majority of the founder members of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade had been Quakers. Meanwhile some of the most vocal abolitionists, notably William Wilberforce, were evangelical Anglicans who worshipped at Holy Trinity Church on Clapham Common; they came to be known as the ‘Clapham Sect’ or, not entirely respectfully, the ‘Saints’.

In the West Indies, the planter class had long tried to keep the enslaved population as ignorant of Christianity as possible. Recently, however, a battle for their souls had broken out in Jamaica, stirred up by Wesleyan missionaries preaching the creed that all men were equal in the eyes of God. The House of Assembly, observing how the ‘dark and dangerous fanaticism’ of the Methodists seemed to resonate among the black population, resolved to spread ‘genuine Christianity’ among them.[21] The Rev. George Wilson Bridges came to Jamaica in 1816, at the invitation of the governor, and was installed as rector of St Mark’s Church in Mandeville, the capital of the newly formed parish of Manchester. Bridges was almost certainly the most active of the Anglican clergymen who were recruited by the authorities to tend to the spiritual needs of the enslaved population; he would later claim to have baptized 9,413 slaves.[22] These ceremonies involved the candidates gathering ‘either at the churches, or on the estates, sometimes from fifty to a hundred or more’. No religious instruction was given beforehand; they were merely asked what their Christian names and surnames were to be, and then ‘baptized en masse, the rector receiving half a crown currency for each person’.[23]

Two estates belonging to Lord Balcarres – Martin’s Hill and Marshall’s Pen – were in the parish of Manchester, and Bridges baptized 220 of the enslaved population there in December 1818 and January 1819. Further west, in Westmoreland Parish, the Rev. James Dawn baptized 121 ‘Negroes belonging to Dean’s Valley Dry Works’, as the church records describe them, on 17 November 1820. One-third of the inhabitants of this estate took one of two surnames – of course, we will never know to what extent these were their own choice, or foisted upon them. Two Amelias, Eliza, Elizabeth, George, James, Mary Ann, Robert, Thomas and William – they would be known as Clayton. Alexander, Amelia, Andrew, Catherine, Diana, Eleanor, Eliza, Elizabeth, George, Henry, three Jameses, Jannett, John, Lucea, Margaret, Mary, Mary Ann, Matthew, Rebecca, Richard, Robert, Romeo, two Susans, Thomas and three Williams – they were all now Atkinsons.[24]

By this time, the long-term decline of the enslaved population at Dean’s Valley had reduced the estate to near paralysis. Back in 1797, there had been 221 slaves on the property; now just 134 were left. ‘Unless the strength is increased,’ wrote the Kingston house, ‘we contemplate not a falling off in the Crop but the utter impossibility of carrying on.’[25] As the debts on both the Bogue and Dean’s Valley estates escalated, and the value of sugar plantations slumped, the Claytons attempted to clear the legal path to their sale. Michael Clayton – Nathaniel and Dorothy’s fourth son – managed the business from the London chambers of the family firm at 6 New Square, Lincoln’s Inn.

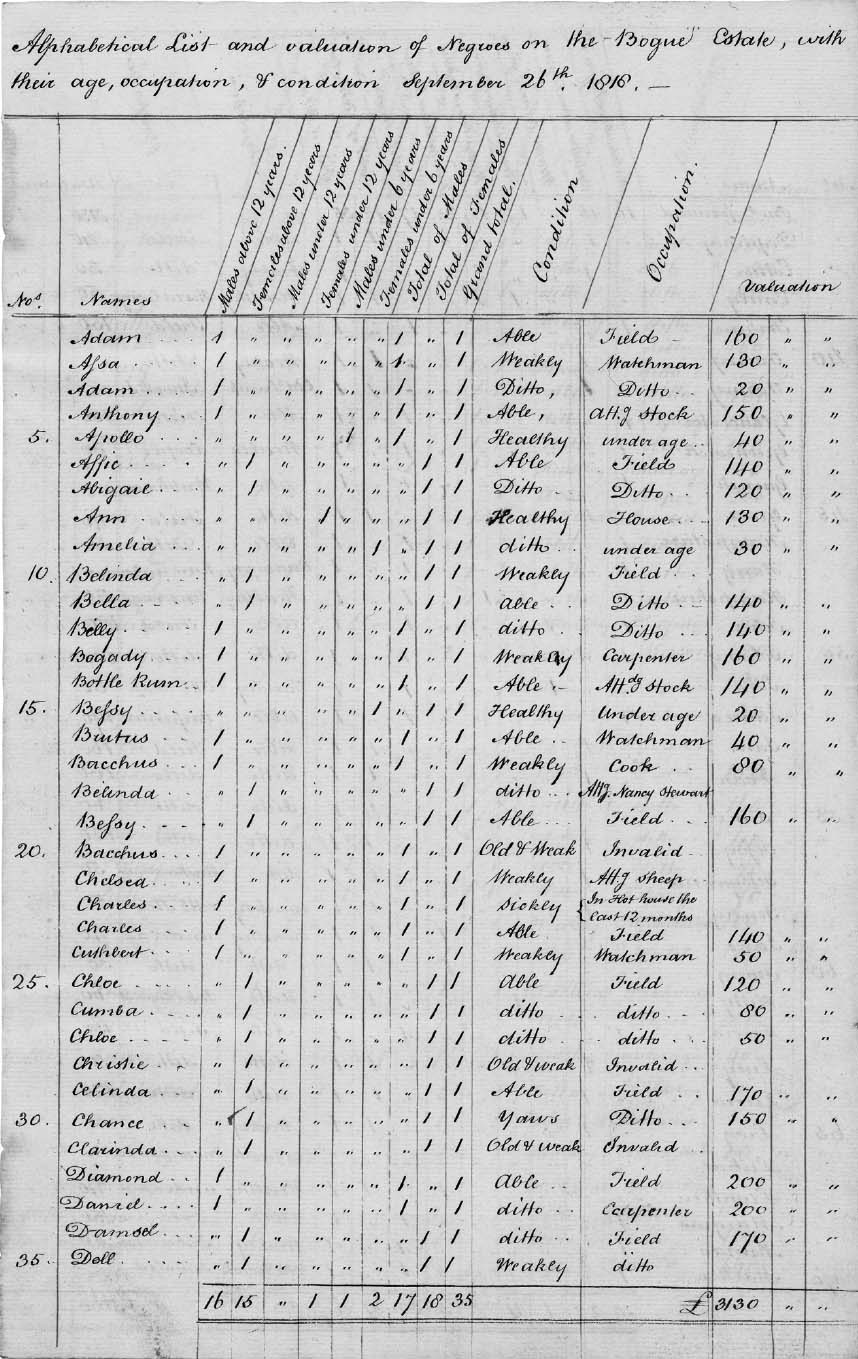

A valuation of the enslaved population on the Bogue estate in September 1818.

National Library of Scotland

But Michael Atkinson’s refusal to go along with his relatives’ wishes presented an obstacle to the properties’ disposal, causing Nathaniel to file two chancery bills against his brother-in-law. Michael wrote to Lord Balcarres in October 1818, complaining of not having received ‘one Shilling’ from the estates while they were managed by those who would now sell them ‘in Liquidation of Debts due to themselves’, and seeking to form an alliance against the lawsuits.[26] But Balcarres brushed him off: ‘Your Uncle Richard Atkinson left his affairs in that State of Confusion & perplexity as to convince me that I could be of no manner of use.’[27]

One day around this time, while he was poring over his uncle’s will at Doctors’ Commons, Michael noticed that it no longer bore its original seal; and so, in January 1819, he filed a ‘voluminous’ bill to have the document set aside as defective.[28] Although Lady Anne Barnard felt a degree of sympathy for Michael, she realized he was entirely the puppet of lawyers who saw a ‘good suit for them out of it’, and declined his invitation to join the legal action.[29] It would prove a wise decision.

The case finally came before the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Charles Abbott, on 1 August 1821. The Solicitor General started by informing the jury that it was their duty to decide upon the legitimacy of a will which had been ‘in operation’ for more than thirty years; the seal it had once borne had ‘by time or accident’ been lost, and now the testator’s nephew had chosen ‘for the first time’ to suggest that his late uncle had deliberately torn it off ‘as a mode of cancelment’. Two employees of the Prerogative Office suggested that the damage might easily have taken place at Doctors’ Commons, given that the ‘practice was to carry the will into the great room, where as many as 200 persons were frequently collected at the same time, and where, of course, to attend to the conduct of every one was impracticable’.[30] Michael could offer no evidence to support his argument – and thus, unsurprisingly, the jury pronounced Richard Atkinson’s will to be completely valid.

SINCE HIS RETURN from India some seventeen years earlier, Michael had expended much of his remaining energy on pointlessly feuding with his relations over their Jamaican inheritance; but this would be the final lawsuit to go against him, for he died six weeks later at his Portland Place residence. Michael’s daughter Sophia had five years earlier married Bertie Cator, a good-natured naval captain, and the Cators now stood to inherit a considerable fortune. But Michael’s obstinacy had exacted a heavy toll on the rest of the family, and the Claytons, being lawyers, now came up with a legalistic way to settle the score.

The inheritance of landed property in Kent had, since Anglo-Saxon times, followed the laws of tenure known as ‘gavelkind’, which determined that in cases of intestacy without legitimate issue, it should be divided among male next of kin – all land in the county was included, unless specifically ‘disgavelled’. Michael had made his will in 1807, naming his daughter Sophia as his lawful heir. He had purchased the Mount Mascal estate the following year, but had failed to update his will in order to disgavel the property. And, furthermore, the family had always strongly suspected that Michael had never married his ‘wife’.

Nat Clayton spelled out the potential implications in a letter to his uncle Matt at Carr Hill. ‘Supposing the Illegitimacy of Mrs. Cator,’ he explained, ‘it would follow, that you as surviving Brother take one half of the Mount Mascal Estate and that the five sons of your deceased Brother George take the other half amongst them in equal Shares.’[31] Nat made some enquiries, and found three highly respectable gentlemen – a director of the East India Company, an East Indiaman captain and an army general – who were prepared to swear affidavits. ‘We have been hitherto very fortunate in obtaining Information relative to Michael Atkinson’s Affairs; & a curious History it will turn out,’ Nat told his mother, Dorothy, on 21 November 1821. ‘In the course of our Inquiries one thing has led to another in an extraordinary Manner; & we have met with ample Information in Quarters where we had the least reason to expect it. The Begum’s Life in point of singularity & variety looks more like a novel than a reality.’[32]

The word ‘begum’ was a term of respect on the Indian subcontinent. Nat was using it ironically, of course – for it appeared that Michael’s ‘wife’ had lived a dissolute youth, to say the least. The story of Miss Sophia Mackereth had begun in London during the 1780s, where as a ‘girl of the Town’ she had been entangled with John Manship, an East India Company director; he had ‘got rid of her by sending her off to Madras’. As soon as she landed in India, in July 1785, she had apparently ‘made a great outcry’ that a trunk containing her jewels and letters of recommendation had been stolen. ‘The whole story was a fabrication,’ recalled Joseph Dorin, captain of the Duke of Montrose. ‘The people of Madras were imposed upon by it & treated her with great kindness.’ Soon afterwards she took up with a Mr Woolley, with whom she stayed for a few months before they fell out; he later died in a duel. She then sailed up the coast to Calcutta, where she was invited ‘from motives of compassion’ to live in the residence of the governor, Sir John Macpherson; finally, in May 1786, she had run off with Michael Atkinson. General Mackenzie, commanding the 78th Highlanders, remembered spending several days with Michael at Jangipur in 1797: ‘He had at that time a Lady living with him who took his name. In the course of conversation I asked him if he was married to her to which he replied without hesitation that he was not.’[33]

Although Matt stood to benefit most, the rest of the family deliberately excluded him from these discussions. ‘Brother Matt must not be trusted with any one thing,’ Jane reminded Dorothy, ‘for the Weakest of Creatures may impose upon him.’ Both sides showed a readiness to fight their corner; Sophia Cator declared herself prepared ‘to go through fire & water’ to prove her legitimacy.[34] ‘My Father would tell you that the Begum or rather Capt. Cator is determined not to give up Mount Mascall without a hard struggle,’ Michael Clayton told his mother on 13 July 1822. ‘I met the Captain a few days ago accidentally and what will surprize you the introduction on his side was attended with the most cordial & hearty shake of the hand notwithstanding the exertions he knows I am making against his Interests. The subject was only slightly adverted to and Capt. Cator said it gave him of course great pain but he knew that we were only doing our duty – there is no difference of opinion as to his worth.’[35]

By this point, the parties were hammering out a compromise. Bertie Cator ultimately agreed to pay £14,500 – which was how much the Claytons calculated that Michael’s refusal to agree to the sale of the Jamaican estates ‘when implored to do so’ had cost the rest of the family – to his late father-in-law’s male next of kin.[36] Matt received a memorandum relating to his half-share of the proceeds, in his nephew John Clayton’s handwriting: ‘By the agreement now executed, Mr. Matthew Atkinson agrees to relinquish all claim to the Mount Mascall Estate on having the sum of £7250 secured to him upon it to be paid on the 5th day of August 1834 unless Mrs. Michael Atkinson shall die before that time in which case the principal money is to be paid within 12 months after her decease.’[37]

The episode must have been excruciating for Sophia Cator, the Begum’s daughter, but soon afterwards she appears to have written in conciliatory language to her uncle Matt. This letter has not survived, although Matt’s reply hints at his great relief that the matter was closed:

I know very few things that would have added so much to the very satisfactory & amiable compromise that has recently been made, as the receipt of your affectionate letter today. I think you know me well enough, my dear Sophia, to doubt a moment of my embracing in the most lively manner the kind & friendly terms proposed & burying all that has past in oblivion, you little know how anxiously I have always hoped some fortuitous circumstance might restore the lost affection of my deceased brother, but Providence ordered it otherwise.[38]

IN MAY 1823, aged seventy-two, Lady Anne Barnard composed a letter to her brother Lord Balcarres, to be opened after her death: ‘You will not receive these few lines till I am no more – they are only to bid you adieu in the anxious hope of meeting you again in a world of everlasting Happiness and love. I wish my funds were as ample as they ought to be, but I will still hope that something may be gained to your family by my means.’[39] Anne was in a leave-taking frame of mind, putting her papers in order and making them fit for the prying eyes of the next generation. Much of her correspondence ended up on the drawing room fire; happily, she spared a bundle of Richard Atkinson’s old letters. ‘Most interesting & noble man’, Anne pencilled at the top of the letter in which he had proposed marriage to her.[40] ‘A strong & solemn testimony of the motives which governed the conduct of this Excellent man’, she wrote on the letter he had sent her alongside the final draft of his will.[41] ‘May we not call him the prince of English merchants?’[42]

Meanwhile, with Michael no longer around to block the business, the Atkinson estate was crawling towards a final settlement. By the close of 1822, terms had been agreed for the sale of Dean’s Valley – the land, buildings, enslaved workers and livestock fetching just over £16,000 – and a prospective buyer had also been found for the Bogue. (‘I hope we shall soon be able to submit to the Trustees for Sale a proposal for getting rid of this disastrous Property,’ Michael Clayton told Lord Balcarres on 18 November 1823.)[43] Meanwhile, Richard Atkinson’s heirs had mostly learnt to manage their expectations. ‘I quite despair of Receiving a Shilling from our uncle’s Effects,’ wrote Joseph Taylor, the son of Richard’s sister Margaret, on 10 March 1824. ‘Indeed I dismiss the Subject from my Mind, and almost wish that no Part of my Family or myself had been mentioned in the Will.’[44]

The Master in Chancery finally made his report on the Atkinson estate at the beginning of 1825. A notice in The Times called on the Mures’ remaining creditors to gather on 29 March at the Court of Commissioners of Bankrupts in the City of London, ‘to assent to or dissent from a compromise of all matters depending between the estate of Richard Atkinson, and the estate of the said Hutchison, Robert and William Mure’.[45] Here the terms of the settlement were agreed ‘to the satisfaction of all parties’.[46] Richard’s estate was in the end valued at £88,000. (Forty years earlier, it had been reckoned worth £300,000.) More than three-quarters of this sum went to the heirs of George Atkinson and Sir Francis Baring, to pay off their loans to the two Jamaican estates, leaving about £20,000 to be shared out among the extended family. As for Lady Anne Barnard’s inheritance – had there been anything for her, it would have been too late, for she died on 6 May 1825.