TWENTY-ONE

![]()

Human Relics

THE CLASSIC NARRATIVE ARC of a family’s fortune spans three generations – the enterprising first generation amasses it, the complacent second generation sits on it, the feckless third generation squanders it. (Although my family doesn’t entirely fit this template – not least because, for some truly world-class fecklessness, it would have to wait till the sixth generation.) At this point in the saga, as the second generation withers and the third generation emerges, the family splinters into branches of cousins, too numerous to follow individually.

A little confusingly, two George Atkinsons inhabit this next part of the story. (As I’ve already mentioned, my forebears were unimaginative where first names were concerned.) The more prominent of these Georges is George and Susan’s eldest son, a Kingston merchant; I’ll sometimes refer to him as cousin George. The other George is Matt and Ann’s eldest son, a Newcastle naturalist; he’s either George or, more formally, George Clayton Atkinson. In case you’re wondering, I’m descended from his youngest brother, Dick – and it’s down this branch of the family that I will be increasingly drawn. (At this point, you may be forgiven for sneaking a glance at the family tree near the front of the book.)

It’s somewhat hard to reconcile Matt the careless progenitor of many illegitimate children in Jamaica with Matt the devoted paterfamilias at Carr Hill; but it would appear that he and Ann enjoyed a tranquil domestic life. George Clayton Atkinson, in a halcyon recollection of childhood, described mornings starting with his father – who was always first to rise – sneezing twice ‘with much vigour’ as he went downstairs, tapping the barometer as he passed through the hall, and heading outdoors with one or more children in tow. ‘How delicious the remembrance of walking about the garden with him, now is,’ wrote George. ‘He was six feet high, & stooped a little in later years; he used moreover to roll rather in his walk; & I can just fancy him walking along the front walk with his pruning knife in one hand, & Jane or Dick holding the other: stopping now & then to trim a straggling carnation, or stepping over the border to eradicate an unsightly shoot from the far extending root of one of the peach trees.’[1]

Matt and Ann were unshowy people, and their home was simply furnished – as George remembered it, there was just one oil painting in the house, a smoky scene of Tynemouth Castle, which hung over the chimneypiece in the school room. The five children – George, Isaac, Mary Ann, Dick and Jane – were an unruly gaggle with only seven years between them, and it fell to Ann to keep their ‘more fervid schemes’ in check, for Matt was an indulgent parent. ‘My poor father, he certainly had the kindest heart, best temper I ever knew,’ recalled George. ‘Nothing went wrong with him, everything pleased him: whatever happened it was all right, & he gives me in recollection, a finer personification of entire contentment than I remember to have met with.’ On dark winter evenings, Matt would read aloud to the family beside the fire, with a ‘very favourite grey cat’ on his knee, while Ann stitched and the young ones quietly amused themselves.[2] The girls were educated at home by a governess, while the boys went off to board at St Bees School near Whitehaven, and then, to tame their ‘Northern Manners & Dialect’, at the Charterhouse School in London.[3]

If there was one trait that pervaded Matt’s working life, it was an unfortunate allergy to paperwork – this would trigger a short but painful dispute with his brother-in-law Nathaniel, conducted via half a dozen letters in March 1816. A fraud had been uncovered at the Tyne Iron Company; the loss to the firm was nearly £100. The partners, believing Matt to be in daily attendance, were shocked to find that he had not once, during the nine years he had managed its head office, bothered to bestow ‘five minutes on the cashing up of a single page of the Cash Book of the Concern’. Nathaniel was furious, and berated him for his neglect: ‘Your Attendance at the Office, applied as it must have been, was at once a Snare to your Partners, and a Temptation to the unhappy Man, who is now expiating his Crimes.’[4] In reply, Matt complained of having been ‘led into the concern’ in the first place, and of his capital having been ‘locked up so long without any return’.[5] But it was Nathaniel’s suggestion that Ann was partly to blame for his inattention, by insisting that he left the office at midday to be back at Carr Hill in time for dinner, which wounded Matt most of all. ‘It was no arrangement of my Wife’s that obliged me to it,’ he wrote, ‘but my own taste for early hours as I can with Truth affirm that she has devoted herself entirely to my wishes since we married, and I may add her utmost pride has been in doing so, you may easily imagine how much we were both hurt at the insinuation of her not entering into the interest of her husband.’[6] Nathaniel terminated the exchange with a wish to ‘bury the Subject in oblivion’.[7]

Matt was most in his element when out rambling with his friend John Hodgson, the local parson. Hodgson took a close interest in the Roman wall; indeed, through the study of inscriptions on excavated rocks, he would reach what was, for the time, the unorthodox conclusion that the emperor Hadrian had been its builder. During one of their long walks, Matt had been delighted to show Hodgson the words PETRA FLAVI CARANTINI – ‘the rock of Flavius Carantinus’ – carved on to a ridge of hard sandstone on his brother-in-law Henry Tulip’s Fallowfield estate.

The two men set out on another trip to Westmorland in May 1817. This was a period of great geological discovery – William Smith’s first map of England and Wales, delineating their different rock strata, had been published two years earlier – and Hodgson, the son of a Shap stonemason, had always been fascinated by the diverse geology of his native county. Over several days, they would together examine the ‘limestone, schist, and sandstone’ in the bed of the River Lowther near Askham, the ‘thin laminae and lumps of fibrous white gypsum’ by the River Eden at Winderwath, and a ‘bed of peat-coal’ by the River Eamont.[8]

The view across Ullswater.

This time, incidentally, Matt and Hodgson did not sleep at Temple Sowerby; instead they put up twelve miles away, beside Ullswater, as the guests of Matt’s sister-in-law Elizabeth Littledale and her husband Captain John Wordsworth, a cousin of the celebrated poet. The Wordsworths’ residence, Eusemere, had been built by the great abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, after repeated setbacks had driven him to seek peace in the Lake District during the late 1790s. The house was built of rough stone and roofed in local slate; its casement windows framed magnificent views. William and Dorothy Wordsworth had often visited the Clarksons there; it was while they were walking along the lake shore, on their way home to Dove Cottage, that they had observed the ‘long belt’ of daffodils, ‘about the breadth of a country turnpike road’, which had inspired Wordsworth to write his most famous verse.[9]

Matt and Ann would pass on their great love of nature to their children; while he issued them with ‘grave injunctions’ not to touch birds’ nests during the breeding season, she encouraged them to press wildflowers between the pages of books.[10] During the summer holidays of 1825, while thirteen-year-old Dick was staying with Aunt Jane at Temple Sowerby, he came across the nest and eggs of a bird that he did not recognize. Back home at Carr Hill, he consulted the well-thumbed family copy of Thomas Bewick’s Birds and identified them as belonging to a pied flycatcher, although he did notice that the author seemed unclear about certain aspects of the species.

Bewick was one of the Atkinsons’ neighbours, and something of a Tyneside celebrity. He had stayed with Matt and Ann at Carr Hill in August 1812, while recovering from pleurisy, and afterwards moved to a house at Gateshead, on the road into Newcastle. During his long career as a wood engraver, Bewick had illustrated many subjects; but rural scenes were his forte, often including minuscule details that revealed a wicked sense of humour. His enduring masterpiece, however, would be his two-volume History of British Birds, which first appeared in 1797. (Fifty years later, Charlotte Brontë would start Jane Eyre with her beleaguered heroine finding refuge within its pages: ‘With Bewick on my knee, I was then happy: happy at least in my way.’)[11] Bewick’s artistic medium was dense boxwood, which accounted for the fine detail of his cuts; indeed, ‘so incredulous’ had George III been that ‘such beautiful impressions could be procured from wooden blocks’ that he had commanded his bookseller to call in the blocks for royal inspection.[12]

Dick and his eldest brother George decided to call on the old man to ‘give him the benefit of Dick’s observations’ on the pied flycatcher.[13] Bewick expressed himself delighted to see them and questioned the boy closely on the habits of the bird, ‘taking memoranda on the margin’ of a copy of his book that he used for gathering corrections.[14] Seventeen-year-old George subsequently struck up a firm friendship with Bewick, and would go and sit with him two or three times a week. During one memorable discussion, the old man claimed that if George threw some eels into the pond opposite Carr Hill House, they would soon multiply to ten thousand. ‘I took the hint,’ wrote George, ‘and shortly afterwards, put in two or three buckets full, none of which I have since had the pleasure of seeing.’[15] Another day, Bewick asked: ‘Are you a collector of relics, Mr. Atkinson?’ Barely knowing how to answer such a strange question, George replied in the affirmative, to which the old man responded: ‘Should you like to possess one of me?’[16] He then fumbled in his desk drawer, before handing George a tiny packet. On the paper wrapping was written the following: ‘I departed from the Place – from the place I held in the Service of Thomas Bewick after being there upwards of 74 Years, on the 20 of November 1827.’ Folded within, George found a tooth.[17]

Thomas Bewick’s engraving of the pied flycatcher.

THE SUDDEN DEATH of uncle George Atkinson in May 1814 had led to the winding up of the Jamaican merchant house of Atkinson & Bogle; the partnership which had replaced it disbanded in December 1824, following Edward Adams’ retirement, to be succeeded by Robertson, Brother & Co. The new firm took over the wharves and warehouses in Little Port Royal Street, the butchery where the beef for provisioning the navy was prepared, the running of several absentee proprietors’ estates, the contract to supply enslaved pioneers to the army, and sundry other concerns on the island. The Kingston office would be run by Robert Robertson’s 29-year-old brother-in-law, George Atkinson, who had inherited his late father’s share of the firm. Cousin George, who was the only one of his siblings to have been born in Jamaica, and who had been educated at Harrow, was by all accounts an unpleasant individual, with a ‘very great idea of his own importance’ as well as a ‘great lack of common sense & discretion’.[18]

Soon George’s next brother, nineteen-year-old Frank, came out to join him on the island. Frank did not care much for Jamaica – a ‘Dog hole’, he called it – and was particularly struck by the locals’ lack of enterprise, writing home:

It would astonish you to know how science is neglected here, and to see the indolence of the people, whites & all, on that score. There is no doubt that we could obtain the finest vegetable oils in the world, not only from cocoa nuts but from mango and innumerable plants here. And in the streets of Kingston & Spanish Town the Gamboge Thistle grows in abundance, one of the strongest narcotics known, and from which many maintain opium is made and not from the poppy; this is put to no use, commercial or otherwise, and all oil is imported. Bees of various species abound. Notwithstanding the excellent market for wax in the Catholic countries round us, only one man during the last 30 years ever kept them as a source of profit, near Kingston, and he has not had any since the Storm of 1815 which blew them all away.[19]

Frank had anticipated returning to England many years later, with ‘spectacles, a stomach, and the gout’, but he quarrelled badly with George and left the island after just a year.[20] Another brother, William, came and went under similar circumstances; and when Matt Atkinson, in 1827, wrote to his abrasive nephew enquiring whether a clerical position might be available for his seventeen-year-old son Isaac, the reply was a decided negative. Robert Robertson found George’s treatment of his younger siblings unfathomable, and wondered whether it arose from some kind of unfounded terror that they would bring ruin upon him. ‘He certainly makes out his own situation as one of great destitution; and if we were to give full credence to his case, as he has described it, you would suppose him to be on the high road to the Poor House,’ Robertson remarked to Matt. ‘But having been one of his father’s Executors, you will as far as his father’s Estate is concerned, know, that in the distribution which was lately made, he received his due proportion: and for his situation in the house, you would hardly believe, after all he has said, that he cannot for his share be deriving much less than £4000 a year – he may try many parts of the world before he will find the means of doing better.’[21]

IT WAS ESPECIALLY HARD on Nathaniel Clayton, as an unflagging writer of letters, that the use of his right hand would be badly hampered in his later years by gout. Nathaniel’s poor health was a constant source of anxiety to Dorothy; but it was she who would die first, on 3 August 1827, after a combination of medicine and leeches failed to ease a bowel complaint from which she had been suffering.

I found myself moved quite unexpectedly by Dorothy’s death. Early on during my family research, I went up to Northumberland to explore the Atkinson–Clayton correspondence in the county archives; over three exhilarating days, I read my way through six boxes filled with hundreds of letters, and met many family members for the first time. On the afternoon of my last day at the archives, as closing time approached, I had almost finished going through the final box. Right at the bottom, I found a small roll of paper, the size of a cigar, on which I noticed that Nathaniel had inscribed, in the shaky handwriting of his old age, these words: ‘A lock of my beloved wife’s hair.’[22] I unrolled it, taking care to disturb the contents as little as possible. The hair was mousy brown, very fine, with just a glint of silver. I fought to hold back the tears when I realized what was happening. I was reaching across five generations and touching – yes, actually touching – my great-great-great-great-aunt.

Dorothy’s death was the first of a run of family bereavements over the next few years. I feel bad that Ann hasn’t been a more conspicuous presence in these pages, especially given that she is my direct ancestor, but this is due to none of her letters having survived. One morning in October 1828 she was pacing up and down the breakfast room at Carr Hill, talking with her son George, when suddenly she grabbed the chimneypiece, murmuring, ‘I feel very queer almost as if I was tipsy.’[23] Matt was called in from the garden, and he took her up to her room. She had suffered a massive stroke; soon she was unable to speak, and paralysed down her left side. Aunt Wordsworth rushed across country from Cheshire and found her sister ‘still living tho’ totally insensible to every thing’.[24] Within three days, Ann was dead.

At the time the younger Atkinson boys, Isaac and Dick, were in Liverpool, where they were apprenticed to the merchant house of J. & A. Gilfillan (an arrangement made through their well-connected Littledale uncles). George, in the meantime, was being groomed for a managing role at the Tyne Iron Company, while also acquiring a local reputation as an upstanding young man. On 24 January 1829, the Newcastle Courant ran the story of a boy who was skating on the pond at Carr Hill late one afternoon when he fell through the ice; he would have drowned but for George, who ‘threw himself in, and by great personal exertion, and at the greatest risk of his own life, succeeded in rescuing his friend’.[25] In the summer of that year, aged twenty-one, George was elected to the committee of the newly founded Natural History Society of Northumberland, his first gift to its collection a ‘very beautiful specimen of the Stormy Petrel’ which he had shot over the Tyne.[26] As the society’s curator for ornithology, George was responsible for soliciting donations from far and wide. The celebrated naturalist John James Audubon contributed the ‘Skins of thirty Birds’ in August 1830; he had visited Thomas Bewick at Gateshead three years earlier, while raising money for his own magnum opus, The Birds of America.[27]

Following Ann’s death, Matt cut a shadowy, shambling figure, and his failing eyesight meant that he could barely read or write; he died on 24 December 1830. I couldn’t locate a copy of his will in the usual public archives, and it took me a while to track one down to Durham University Library.[28] I was curious to find out whether Matt had in the slightest way acknowledged his ‘other’ family – but this would prove wishful thinking on my part. Whatever happened in Jamaica, stayed there.

‘WHO KNOWS BUT that emancipation, like a beautiful plant, may, in its due season, rise out of the ashes of the abolition of the Slave-trade,’ Thomas Clarkson had written in 1808, the year the landmark act came into force.[29] His optimism had not been entirely misplaced, for the institution of slavery showed signs of crumbling; in the early 1820s, though, its collapse still seemed some way off. The inaugural meeting of the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery took place on 31 January 1823; abolitionists now set out to present themselves as pragmatists, not seeking immediate emancipation, instead hoping to ‘improve, gradually’ the lives of the enslaved population by giving them greater protection under the law, and conferring upon them ‘one civil privilege after another’, until one day they would rise ‘insensibly to the rank of free peasantry’.[30] William Wilberforce, who was too infirm to lead the parliamentary campaign, passed the baton to Thomas Fowell Buxton, the MP for Weymouth.

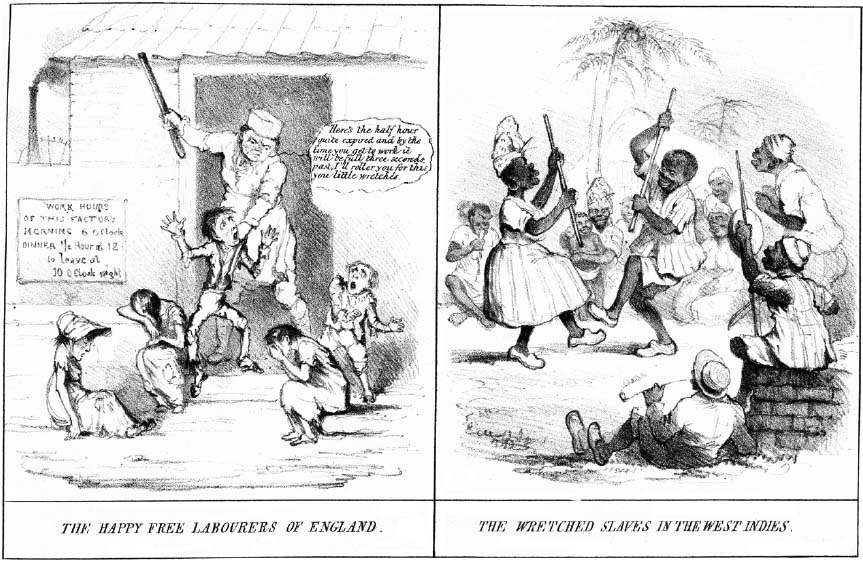

On 15 May, in the House of Commons, Buxton moved a resolution that slavery was ‘repugnant’ to both the British constitution and the Christian religion, and ‘ought to be gradually abolished’.[31] Alexander Baring – Sir Francis’ second son – warned that should abolition take place, the sugar islands would be of no further value to Britain. He also insisted that the hardships endured by the enslaved population had been much exaggerated: ‘The name of slave is a harsh one; but their real condition is undoubtedly, in many respects, superior to that of most of the peasantry of Europe.’[32]

This mischievous argument – that the enslaved people of the West Indies were ‘as well, or perhaps even better’ off than European labourers – was one to which pro-slavery lobbyists resorted with such frequency that Thomas Clarkson set out to debunk it in a polemic using adverts drawn from the Jamaica Gazette.[33] The first example he gave was as follows: ‘Kingston, June 14th, 1823. For Sale: Darliston-Pen, in Westmoreland (Parish), with 112 prime Negroes, and 448 head of stock.’ (Darliston was a cattle ranch owned by the Kingston house – thirty-eight of its enslaved population had taken the surname Atkinson when they were baptized three years earlier.)[34] ‘I stop now to make a few remarks,’ Clarkson wrote. ‘First, it appears that the slaves in the British colonies can be sold. Can any man, woman, or child be sold in Britain? It appears, secondly, that these slaves are considered in no other light than as cattle, or as inanimate property. Now, do we think or speak of our British labourers or servants in the same way?’[35]

Over the next few years, the government attempted to straddle two diametrically opposed viewpoints through the policy known as ‘amelioration’, by which the enslaved population would be gradually prepared for their liberty. The Colonial Secretary Lord Bathurst, in consultation with the Society of West India Planters and Merchants, drew up a programme of measures that the legislative bodies on the individual islands were then pressed to adopt. Religious instruction would be given to enslaved people, and marriages between them would be encouraged; families could not be separated by sale; enslaved women could no longer be punished by flogging; enslaved men could receive no more than twenty-five lashes.

The lot of ‘the happy free labourers of England’ is contrasted with that of ‘the wretched slaves in the West Indies’.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Cousin George Atkinson was elected to the Jamaican House of Assembly in 1826 as one of Kingston’s three representatives. The members for the town were seen as radicals: ‘They are strenuous opponents to the Saints and Lord Bathurst, and all attempts at legislating for the Island.’[36] The Assembly saw Bathurst’s ‘ameliorative’ measures as outrageously meddlesome, of course, but nodded them through nonetheless; believing emancipation to be inevitable, they were now focusing their energies on capitulating to the will of Westminster under the best possible financial terms. ‘Compensation’ had become the planters’ watchword.

By the start of the 1830s, however, many abolitionists had lost patience with the government’s softly-softly approach to their cause. On 15 May 1830, at a rowdy meeting of more than two thousand activists at the Freemasons’ Hall in London, a resolution passed to demand that parliament set a date after which all newborn babies would automatically be free. ‘They ought to aim at the extinction of slavery, by taking off the supply of children,’ declared Thomas Fowell Buxton.[37]

But first, before it was ready to liberate the enslaved population of the colonies, parliament would need to put its own house in order. The system by which the British electorate picked their representatives was indefensibly archaic, with most of the swelling middle classes still excluded from the franchise. The constituency map portrayed a bygone age, where tiny rotten and pocket boroughs such as Old Sarum and New Romney continued to return two MPs, while the booming northern industrial city of Manchester – an abolitionist heartland – lacked even one representative.

The summer of 1830 saw the eruption of the ‘Swing riots’, as disaffected agricultural labourers rallied under the battle cry ‘Bread or Blood’ and set about torching haystacks, barns and farms. The unrest soon spread from Kent, where it had started, across much of England. Many among the ruling class accepted that electoral reform was overdue. ‘The state of England is truly grievous but there is no remedy except by the aristocracy holding together to preserve the Peace,’ Bertie Cator, who was close to the action at Mount Mascal, wrote to Jane Atkinson at Temple Sowerby. ‘Tho I speak of Aristocracy holding together I don’t mean we ought not to yield to public opinion. I am anxious for Reform because it appears requisite. I mean that people who enjoy wealth should exert themselves to preserve Peace and good order.’[38] (In spite of all the unpleasantness which had gone before, cordial relations now existed between the Cators and the rest of the family.)

On 22 November, following the defeat of the hidebound Duke of Wellington in a motion of no confidence, Earl Grey pledged his new Whig ministry to pushing through the necessary legislation. Three months later, Lord John Russell placed a reform bill before the House of Commons; it scraped through its second reading by one vote, but was sabotaged by a wrecking amendment during the committee stage. Grey immediately took the risk of forcing another general election, and in July 1831 he won the thumping landslide that would pave the way for change.

JAMES LINDSAY, the seventh Earl of Balcarres, viewed the management of his recently inherited Jamaican plantations with considerable distrust. Following his father’s death in 1825, he had gone through the old estate accounts, as submitted by the Kingston house, and was shocked to find that they had barely turned a profit in seven years. It was true that the coffee estate in St George Parish, plagued as it was by frequent landslides and a ‘turbulent’ workforce, had been failing for a long time; but the poor performance of the adjoining Martin’s Hill and Marshall’s Pen properties, in Manchester Parish, was harder to swallow.[39] For here, under George Atkinson’s direction, and at vast cost, 140 acres of woodland had been felled and planted with coffee; a works had been built, a pulper installed and extensive patios laid on which to dry the beans; and three hundred acres of guinea grass pasture had been added, enclosed by three miles of dry-stone walls.

The new Lord Balcarres was far from reassured by a private letter from Edward Adams, who, as a former partner of the Kingston house, knew the estates well. With startling candour, Adams warned that he had never known West India properties to be ‘ultimately profitable’ to absentee proprietors. ‘Subject to Hurricanes, Rebellion, Emancipation, Contagion among Slaves, at best their returns are precarious,’ he wrote. ‘You always are at the mercy of your local Agent, and each of them in turn, speciously and with glittering anticipations may undo the act of his Predecessor by an idle Expense of Thousands. You cannot sell it but on credit, and to recover the amount, you must wade thro’ Chancery; and on selling, if you get the value of the Slaves and Cattle, your Land and Works you are well contented to sacrifice!!’[40]

George’s letters to Lord Balcarres brimmed with his high hopes for the estates, but less rosy reports reached their owner by other channels. The overseer at Martin’s Hill disclosed that the Kingston house, which held the contract to supply the navy’s beef, regularly used the pasture there to fatten up ‘their own Cattle’.[41] On one occasion, only a small proportion of a cattle shipment from Puerto Rico had been safely delivered to Martin’s Hill; and George’s explanation that the rest had died in transit had failed to satisfy their purchaser. ‘The whole transaction about these Spanish Cattle is most disgraceful, & almost dishonest,’ wrote Balcarres. ‘I have no doubt he has made a pretty penny of the transaction, & pandered upon me what is not worth any thing like the value charged.’[42]

Jamaican attorneys were notorious for their chicanery, and it is not hard to reach the conclusion that George was plotting to seize these estates for himself, by saddling them with so much debt that their owner would consider it almost an act of mercy to be relieved of them. Lord Balcarres certainly believed this to be the case, but he faced a ‘very delicate’ predicament – for were he to appoint a new attorney to manage the estates, George would no doubt do his damnedest to cut him out of his one-third stake in the lucrative pioneer business.[43]

On 1 January 1830, cousin George wrote to inform Lord Balcarres that his partner Robert Robertson would soon be retiring. He would continue to run the house in Jamaica, while James Hosier, who had previously managed the dry goods branch of the business, would now represent its interests in England; and he trusted that his Lordship would show the partnership of Atkinson & Hosier the same ‘confidence’ that he and his father had been pleased to confer upon its predecessors.[44] At this point, Balcarres contemplated cutting loose, but Edward Adams offered one clear nugget of advice – on no account should the earl jeopardize his interest in the pioneer business. ‘Consider the immense returns on the amount of their Investment that they regularly yield,’ Adams wrote. ‘What would you get for them, if sold? Depend on it, not a Fraction more than the intrinsic worth of the men, and nothing in consideration of the productiveness of the Contract.’[45]

And so, for the time being, Lord Balcarres’ estates languished under the management of the Kingston house. ‘They hope that I shall be satisfied with the improved state of Martins Pen, having 95 head of Cattle more than the last year, but they here omit to state, that most of these Cattle have been purchased and a debt incurred,’ Balcarres observed to his London agent on 6 February 1831. ‘It is like congratulating me that my servants have not robbed my house a second time.’[46] But on 16 May, his mind made up, Balcarres wrote to George Atkinson: ‘It is now upwards of six years since I succeeded to my West India property. It is unnecessary for me to state how much I have been disappointed in the expectations held out to me.’ Having read some recent comments by George about the ‘dreadful state of Jamaica property’, he explained, he no longer believed his own plantations could prosper under the care of an attorney who so evidently thought they ‘must shortly and inevitably be reduced to actual Ruin’; and thus, ‘as Drowning Men will catch at straws’, he had recently dispatched a new power of attorney to a gentleman living close by the Manchester estates.[47]

George reacted with predictable fury to his discharge, firing off a letter listing the great strides taken at Martin’s Hill and Marshall’s Pen under his command: ‘The unprofitable drudgery of getting the property into condition to be profitable has been performed by us, and your new Attorney only reaps the fruit of our exertions.’[48] Afterwards he submitted the estates’ final accounts, of which Balcarres would observe: ‘A more Rascally set of Closing Accounts were never delivered in.’[49]

Meanwhile, the two parties were locked in a bitter dispute over the pioneers. In March 1830, Lord Balcarres had demanded that an ‘absolute conveyance be made out in my own name without loss of time, of my undivided third of the contract, & of the whole of the Pioneers, each Pioneer to be named therein’.[50] But George refused to comply, arguing that since Atkinson & Hosier held the majority stake in the business, they needed shielding against anyone representing the minority interest who might choose to withdraw a proportion of the pioneers, or even terminate the contract: ‘Our object is merely to protect from all possibility of prejudice our own larger interest.’[51] Edward Adams, when shown George’s letter, dismissed these grounds as ‘utter sophistry’.[52]

POLITICAL TENSIONS had long been simmering in Jamaica, where the planter class continued to cling on to every scrap of power; although free people of colour now outnumbered whites by two to one, they were still disbarred from voting in elections or giving evidence in criminal cases, and disqualified from serving in the House of Assembly or holding a commission in the island militia. But finally, in December 1830, the Assembly passed an act declaring that ‘all the free brown and black population’ would be ‘entitled to have and enjoy all the rights, privileges, immunities and advantages whatsoever to which they would have been entitled if born of and descended from white ancestors’ – a milestone in the social and political evolution of the colony.[53]

The island elite had always tried to shield their enslaved workforce from news of outside events. ‘So completely has all intercourse with Hayti been heretofore guarded against,’ wrote one planter in the 1820s, ‘that the slaves of Jamaica know no more of the events which have been passing there for the last thirty years than the inhabitants of China.’[54] But it was impossible to prevent whispers of abolition from circulating round the island. In late 1831, the rumour arose that parliament had voted to end slavery, and that the king had sent papers ordering the liberation of the slaves – but that the masters were conspiring to keep them in chains.

As the story spread, Samuel Sharpe, an enslaved man who was also the charismatic deacon of a Baptist chapel at Montego Bay, convinced his brethren to mount a show of resistance; they would refuse to cut the ripe sugar cane on their estates unless granted their liberty and paid for their labour. Local white missionaries soon heard about the planned strike. ‘I learn that some wicked persons have persuaded you that the king has made you free,’ preached the Baptist minister William Knibb in his sermon on 27 December. ‘What you have been told is false – false as hell can make it.’[55] Kensington Pen in St James Parish was the first of dozens of estates to be set on fire that night, turning the dark sky a sinister shade of orange. The insurrection quickly gathered pace, with perhaps sixty thousand enslaved men and women coming out in support.

By the time the armed forces had restored peace, two weeks later, nearly three hundred properties in the west of the island had been put to the torch. (Not that they belonged to the Atkinson family any more, but both the Bogue and Dean’s Valley estates were damaged.) At least two hundred blacks and fourteen whites died in the conflict, which would become known as the Baptist War. In the reprisals that followed, more than three hundred men were executed in the main square at Montego Bay. ‘Generally four, seldom less than three, were hung at once,’ recalled the Wesleyan missionary Henry Bleby. ‘The bodies remained, stiffening in the breeze, till the court martial had provided another batch of victims.’[56] Meanwhile, vigilante groups adhering to the Colonial Church Union, an organization set up by the pro-slavery Anglican clergyman George Wilson Bridges, destroyed fifteen Nonconformist chapels. Samuel Sharpe was the last of the rebels to be executed, on 23 May 1832. ‘I would rather die upon yonder gallows than live in slavery,’ he told Bleby shortly before his end.[57]

THE REJECTION of a second reform bill by the House of Lords sparked serious disturbances across England during the autumn of 1831; and fears that the violence would continue for as long as the political establishment resisted change were only stoked by the shocking news from Jamaica.

At the start of the next session of parliament, in December 1831, Grey’s ministry tabled yet another reform bill; it easily cleared the Commons in March 1832. However, the recalcitrance of the upper house left the government with little choice but to propose the creation of enough new Whig peers to outvote the reactionaries – a measure which William IV would not consent to. As a result, Grey resigned on 9 May. The monarch invited Wellington to form a new ministry; but the duke failed to build sufficient parliamentary support, and Grey took office again on 15 May. The Representation of the People Act – commonly known as the Reform Act – passed into law on 7 June. It swept away those swamps of vested interest, the rotten boroughs, in their place creating 130 new seats; and it almost doubled the size of the electorate, extending the franchise to small landowners, tenant farmers, shopkeepers and householders paying annual rent of £10 or more.

The general election that followed, under the new franchise, brought in a fresh generation of free-thinking MPs – some representing previously ignored manufacturing towns – who were impervious to the blandishments of the West India lobby. From the start, Grey’s new ministry faced sustained pressure to abolish slavery, with dozens of petitions arriving at Westminster every day. In the House of Commons, on 14 May 1833, the Colonial Secretary Edward Stanley unveiled the principles upon which the government planned to base its abolition bill – but not before Thomas Fowell Buxton and three other MPs had manhandled a ‘huge feather-bed of a petition’ on to the table of the chamber.[58]

Stanley’s proposals fully satisfied no one. To the abolitionists, the suggestion that former slaves should undergo a twelve-year period of ‘apprenticeship’, when they would be obliged to give their former owners three-quarters of their labour in return for food and shelter, smacked of slavery in all but name. To the West India interest, the £15 million loan that would assist the planters’ recovery from this hammer blow seemed derisory. But the House did agree to Stanley’s first resolution, which was that immediate measures should be taken ‘for the entire abolition of slavery throughout the colonies’.[59]

Behind the scenes, the West Indians lobbied strenuously. On 10 June, Stanley informed the House that he believed the proposed £15 million loan was too hard on slave owners. The government now planned to offer them £20 million in outright compensation for the loss of their human property; he had received assurances that this figure would be sufficient to secure ‘their full concurrence and co-operation’.[60] Twenty million pounds was such a vast sum – about 40 per cent of the annual national budget – that it exceeded the comprehension of most MPs, even those accustomed to dealing with enormous amounts of money. ‘The magnitude of the sum almost passes the powers of conception,’ Alexander Baring commented. ‘In the present distressed state of the country, and in the still greater state of distress to which it will be reduced by the failure of this experiment, you might as well talk of £200,000,000.’[61]

By 25 June, the abolition bill was ready to receive its first reading. The debates that followed were largely passionless, and focused on practicalities; at times it seemed that MPs had forgotten who the bill was intended to benefit. ‘I cannot help observing, that, in discussing this question, we do not enough bear in mind that there are such persons as a large black population,’ the veteran reformer Sir Francis Burdett scolded his fellow members. ‘Everybody seems to think that either the commerce of this country, or the property, as it is called, of the West India proprietors, is the only matter of importance.’[62]

The abolitionists’ final objections to the bill concerned the number of years for which the so-called ‘apprentices’ would be expected to continue working for their former masters. They had already accepted that ‘praedial’ slaves – those who were connected to the cultivation of the land – would have to endure longer apprenticeships than ‘non-praedial’ slaves. During the bill’s committee stage, Stanley proposed fixing these terms at six and four years respectively, which was enough of a concession to satisfy the abolitionists. William Wilberforce, who had recently said that he felt ‘like a clock which is almost run down’, heard the news of the breakthrough three days before his death on 29 July 1833.[63] The bill passed the House of Commons on 7 August. Three weeks later, and despite the Duke of Wellington’s last-ditch efforts to hobble it with amendments, the Slavery Abolition Act was signed into law.