TWENTY-TWO

![]()

A Spice of the Devil

NATHANIEL CLAYTON died in March 1832, aged seventy-five, leaving the Chesters estate to his three eldest surviving sons, Nat, John and Michael, and sizeable lump sums to the rest of his children – largesse that he could well afford. He had already secured his legacy in the corporation of Newcastle, having seamlessly handed over the town clerk’s office to John in December 1822.

Nat’s story would be one of potential unfulfilled. As a schoolboy, he had shown vast promise, coming top of the Harrow sixth form exam above Robert Peel, the future prime minister, and Lord Byron, the future literary titan. (Byron later recalled: ‘Clayton was another school-monster of learning, and talent, and hope; but what has become of him I do not know. He was certainly a genius.’)[1] Nat had gone on to practise law in London, where he was appointed a Commissioner in Bankruptcy under the patronage of his father’s childhood friend, Lord Chancellor Eldon. But during his thirties he had been afflicted by a nervous disorder, with symptoms that included involuntary laughter and a difficulty swallowing; and after his recovery, he found that he had no further appetite for business. He would justify his retirement to Northumberland, aged forty-three, in a melancholy letter to his disapproving father:

I should have retired from a lucrative Practice most unwillingly, & certainly not without a struggle. But recollecting that previous to my Illness my professional Prospects frequently induced a Despondency that was very difficult to combat, I felt afterwards that I had neither Health nor Spirits to play what is called the whole game of the Law; & after so long an Interval, I was willing to spare myself the mortification, not to say Humiliation, of pursuing it otherwise.[2]

John, on the other hand, would prove a worthy heir to the Clayton dynasty. After the passing of the Reform Act, it was local government’s turn to face scrutiny, and when royal commissioners turned up to investigate Newcastle in October 1833, John was the first man called to give evidence. George Clayton Atkinson would write admiringly of his cousin’s performance: ‘He seemed to know everything connected with the corporation – understand all the little complicated byelaws, & remembered every circumstance in such an extraordinary way, that he completely astonished the Commissioners, & has done himself immense credit.’[3]

The bustling metropolis of Newcastle, as viewed from Gateshead.

© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images

The Municipal Corporations Act of 1835, which came out of the royal commission, overhauled the local government of 178 towns and cities in England and Wales – and John Clayton emerged unscathed from the upheaval. In 1836, an anonymous Newcastle journalist described him as follows:

Has all the craft and subtlety of the devil. Great talents, indefatigable industry, immense wealth, and wonderful tact and facility in conducting business, give him an influence in society rarely possessed by one individual. Was unanimously re-elected Town Clerk, because the Clique had not a man equal to supply his place. Can do things with impunity that would damn an ordinary man. A good voice, speaks well, and never wastes a word.[4]

Everywhere, the spirit of reform was in the ascendant, and the patronage from which the aristocracy derived so much of its wealth and influence was under attack. William Cobbett was a particular adversary of this ‘old corruption’ through the pages of his newspaper, the Weekly Register. ‘These blades are brothers, I believe, of the Earl of Egremont,’ Cobbett had written about Charles and Percy Wyndham, who reportedly received £11,000 a year between them for an assortment of Jamaican offices. ‘They have had these places since 1763. So that they have received Six hundred and forty-nine thousand pounds, principal money from these places, without, I believe, ever having even seen poor Jamaica.’[5] In the wake of the Reform Act, an investigation into West Indian sinecures was launched; and it was perhaps a tad ironic, given the late Sir Francis Baring’s dealings with Charles Wyndham on behalf of the Atkinson family, that the committee was chaired by one of his grandsons, another Francis Baring, who was an unyielding critic of the patent offices.

CARR HILL NO LONGER felt much like a family home after Matt and Ann’s deaths, and over the next few years their five children would scatter round the globe. But first, in May 1831, two of the boys – George and Dick – embarked on a tour of the western isles of Scotland. George was the driving force, being keen to visit some of the ‘great breeding places of the sea fowl’ and gather specimens for Newcastle’s new natural history museum – a mission into which he threw himself with energy, on one occasion stripping off and swimming out to a rocky island in the middle of a loch on the isle of Harris, dragging behind him with his teeth a ‘water proof bag’ designed for conveying eggs to shore.[6] (Dick, meanwhile, ‘insinuated himself into the good graces’ of the villagers. ‘The old crones,’ recalled George, ‘used to clap him on the back and in their lack of more appropriate English, call him pretty boy.’)[7]

The Atkinson brothers’ final destination was the remote archipelago of St Kilda. To make the sixty-mile crossing from Harris they hired an eighteen-foot yawl crewed by three local men, containing a sack of oatmeal, a peat fire in an iron pot, and half a dozen bottles of whisky. Their first impression of the St Kildans who hauled the boat on to the wide beach was of good health; they had the ‘most beautiful teeth imaginable’.[8] The islanders, the brothers discovered, depended upon birds for their every need: ‘Except from the rocks, fishing is not pursued, for they have only one very clumsy boat, and manage it miserably; so in fact, fowling is their only occupation.’[9] Dick’s terrier, Crab, soon became expert at extracting puffins from their burrows, ‘for he is so small, that the larger holes easily admitted him, and the bites he at first received only made him more determined’.[10] On their third and last morning at St Kilda, some boys presented them with a pair of young peregrine falcons that they had plucked from a nest on a precipitous cliff; George took the hawks back to Carr Hill, hoping to observe ‘their progressive changes of plumage’ as they grew into maturity.[11] But it was not to be, for both birds would fly off.

Mary Ann was the first of Matt and Ann’s children to be married, to John Dobson, a Gateshead solicitor. Not long afterwards, in 1833, the couple emigrated to Van Diemen’s Land, in the far-off penal colony of New South Wales. (The territory would be renamed Tasmania in 1856.) By the time of their departure, there was no love lost between John Dobson and his Atkinson brothers-in-law, who were furious that he had drained all the ready money from their late father’s estate, and grief-stricken at the permanent loss of their beloved sister.

Isaac, the middle Atkinson boy, had left for Jamaica in late 1831 – cousin George having agreed to employ him at the Kingston house – but illness forced his return after barely a year away. Soon he was placed under the supervision of a physician at Kirkby Lonsdale in Westmorland, within visiting distance of Aunt Jane from Temple Sowerby. Dick, meanwhile, sailed out to Jamaica to fill Isaac’s shoes. On 10 December 1833, George would write to Dick with news of their brother’s declining health: ‘Poor Isaac – your forbodings that you should never see him again – I fear are too true.’[12] On 24 January 1834, in a feverish state of mind, and haunted by past sins, imaginary or otherwise, Isaac started writing what he clearly knew would be his last letter to Dick in Jamaica: ‘I was as you well know sunk in Every kind of wickedness & set my God at defiance, & mocked him Continually, yet his goodness never tires & when hell was gaping for me he stretched out his arm to me, & has by prayer thro’ Christ so opened my Eyes to a sense of my own insufficiency.’[13] He died on 11 May, aged twenty-four, and was laid to rest in the churchyard at Temple Sowerby.

DURING THE TWILIGHT days of slavery, the Kingston house was one of the few active participants in the market for slave labour in Jamaica; in a sense it was bound to be, for it remained subject to a £10,000 bond that guaranteed its performance of the pioneer contract. In November 1832, cousin George Atkinson agreed to supply forty-eight pioneers to the 37th Regiment; as a result, he would purchase forty-one men over the following twelve months. As it happens, the last pioneer he bought, for £45 currency on 23 October 1833, was an individual called Richard; this was during the slender gap between the passing of the Westminster abolition act, on 28 August, and the corresponding local law, on 3 December.[14] The House of Assembly in Jamaica was the first colonial legislature to ratify its own abolition act; to stall would merely have delayed the distribution of the £20 million compensation money, a process that could not commence until all nineteen slave colonies had enacted legislation deemed adequate by Westminster.

One of the first deeds of the Slave Compensation Commissioners, operating out of Whitehall, was to order a full census and valuation of the enslaved population throughout the empire; the governor of each colony appointed men to manage the process locally. George Atkinson was named one of Jamaica’s eight assistant commissioners in February 1834, but he did not hold the post for long. That same month, the local Court of Chancery awarded him the receivership of Norwich estate in Portland Parish, prising the property out of the hands of James Colthirst, its indebted owner. Colthirst, who had served as a clerk at the Kingston house for fifteen years, soon took revenge by revealing to the partner of a competing merchant house that George had knowingly embezzled $5,000 which had been mistakenly overpaid while settling a transaction back in 1819. The rival merchant sued for the return of the funds, the case coming to trial in July 1834. In the face of some damning evidence, the judgement went against George, and although this was only a civil case, not a criminal one, it left a stain on his character. George was discreetly advised to retire from the compensation board, and took the hint. ‘I have just received from him a tender of his resignation on the grounds of ill health,’ the governor, the Marquess of Sligo, wrote to Thomas Spring Rice, the Colonial Secretary. ‘I have accepted, and trust that you will approve of my adopting this mild course in preference to one more painful to his feelings.’[15]

The start of the ‘apprenticeship’ – the period during which it was envisaged that former slaves would learn to live freely – passed without incident on 1 August 1834, which surprised many whites who had prophesied bloodshed. ‘I for one certainly expected a much more serious difficulty to have followed on a change so entire & so sudden,’ wrote George. ‘I augur well for the Colony even after the Apprenticeship ceases. The embarrassed Mortgagor must go and the overforced cultivation of sugar must decline but another & in my opinion a healthier state of cultivation will ensue.’[16]

The enmity between Lord Balcarres and the Kingston house would erupt again during the compensation process. According to rules published in the London Gazette, all claims for a slice of the £20 million compensation money needed to be filed within three months of the start of the ‘apprenticeship’. By this date, 31 October 1834, cousin George had submitted nine claim forms for the pioneers – encompassing 255 men based in seven parishes – under his own name as ‘joint owner with James Hosier’. Balcarres’ one-third interest was not mentioned on the paperwork, since the rules specified that claims should be made by those whose names had appeared on the ‘latest returns made in the office of the Registrar of Slaves’ – and the earl’s share of the pioneers remained unregistered.[17]

Since his dismissal by Lord Balcarres three years earlier, George had made a point of providing the earl with only vague accounts of the pioneer business, of withholding his income for as long as possible, and of using his properties without permission as places of retirement for old and infirm pioneers. ‘With respect to the House of Atkinson I really do not know what is to be done with them,’ Balcarres wrote to his London agent. ‘Their undoubted intention is to cheat us in the winding up of the Pioneers if they can, & of course our policy is to prevent them if we can, & it is clear that they will furnish no information unless they are forced to it by Law.’[18]

Although George had shown himself to be devious, it may be that Lord Balcarres was here being unnecessarily suspicious. While it was perfectly true that George and his partner James Hosier had refused to place Balcarres’ name alongside theirs on the slave register, they had never disputed his one-third share in the pioneers. Indeed, they had admitted it ‘unequivocally’, and in countless letters; they had also offered him a letter from Barings, their agent in London, guaranteeing his share of any compensation money.[19] Nonetheless, Balcarres chose to file a counterclaim against each of George’s nine claims, a hostile act he defended on grounds of Hosier’s insolent tone towards him: ‘The few letters that he addressed to me personally, were of a description & language, that in this Country no Gentleman makes use of to another.’[20]

In August 1835, the Treasury awarded the contract to supply the majority of the compensation money to a syndicate led by the financier N.M. Rothschild. Meanwhile, in London, the commissioners began the process of adjudicating – colony by colony, and in Jamaica’s case parish by parish – the 46,000 claims they had received to compensate for the loss of 668,000 slaves. By Christmas, the first payments had been made; over the ensuing months, snaking queues of former slave owners and their agents, waiting to pick up cheques from the National Debt Office at 19 Old Jewry, would become a familiar sight in the City of London.

Shortly after his first payment for the pioneers came through, Lord Balcarres wrote to George Atkinson: ‘Perhaps this may be a proper opportunity for me to assure you that it has been a subject of great regret to me, that there has been a considerable degree of irritation in our Correspondence for some time past, and which I submit during the very short time that our connection will now subsist had better be discontinued.’[21] The final cheque for the pioneers was released in April 1836, bringing the total payout for 255 men to £6,577, or £25 per capita.

I spent the best part of a week trawling through Lord Balcarres’ correspondence about the pioneers at the National Library of Scotland. He had kept every letter on the subject, later annotating some with pithy comments. ‘From the House of Atkinson respecting the Compensation Claim for the Pioneers – a Bullying Letter which I answered in his own style,’ he had written on the back of one of George’s notes.[22] ‘A most intemperate ungentlemanlike letter,’ he had scrawled on another.[23] Not for the first time during my investigations, I felt bruised by the ugliness of what I was finding. Lord Balcarres’ distrust of the ‘House of Atkinson’ was completely understandable, but even so I disliked his haughty tone and his assumption of the moral high ground, for neither party had emerged covered in glory. Following this research trip, I wrote to the current earl, who had allowed me access to these papers, mentioning my disappointment that our families should have ended up at loggerheads. I was grateful for the kindness of his reply. ‘My experience of family archives,’ he said, ‘is that each family invariably regard their correspondents as rogues and themselves as innocent gentlemen.’

On top of his portion of the pioneer money, George Atkinson shared in payments for a further 511 enslaved men and women, most of whom were based on three properties where he was acting as receiver – Norwich and Whydah estates in the parish of Portland, and Stanmore Hill in the parish of St Elizabeth. Incidentally, claimants were not required to give the names of their former slaves on the official paperwork, except under exceptional circumstances; the only individual named by George, on account of his having been ‘born in Gt. Britain’ – which meant that compensation could not be paid out for him – was a certain William Robertson.[24]

So who was this William Robertson? Yet again, when it came to matters of mixed blood, the family letters offered minimal clues. All I could find was this: in the 1817 slave register for Kingston, William was identified as the eighteen-year-old ‘mulatto’ son of Flora, a forty-year-old ‘negro’ woman attached to George’s household.[25] So William was born in about 1799, and had a white father. But who might this parent have been? Was it George’s brother-in-law and former business partner, Robert Robertson? Or could it have been George’s own father, George, who had returned to England in 1798, perhaps taking Flora with him as a servant? In this scenario, George and William would be half-brothers – which may sound quite unlikely, but I really wouldn’t be surprised. Having spent so much time poking around in my family’s past, it now takes a great deal to surprise me.

IN APRIL 1835, when Dick Atkinson had been in Jamaica about eighteen months, a violent strain of yellow fever swept the island. George, who was lodging with his young cousin while his own house was being renovated, had the presence of mind to send for a doctor as soon as Dick’s symptoms surfaced. Mercifully, Dick managed to throw off the fever on the third day, after being ‘severely bled & blistered’, a swift recovery that George attributed to his ‘prudent sober manner of living’.[26]

His careful temperament may, perhaps, have saved his life; but Dick was too diffident to flourish as a merchant. ‘All he wants is confidence in himself, & activity – what in the world is termed a Spice of the Devil,’ George (who possessed Spice of the Devil aplenty) told Aunt Jane.[27] ‘His only chance of getting on is to become a clever salesman & good man of business which with the opportunities he has got depends entirely on himself. In temper & steadiness he is all I can wish.’[28]

George and Dick were regular correspondents with their aunt at Temple Sowerby. Jane continued to add to her mother’s collection of shells and other natural wonders, and they were always on the lookout for specimens. ‘My dear Aunt,’ wrote George on 11 July 1836:

I heard from Richard that you were desirous of getting an Alligator and having been fortunate enough to procure one about 5 feet long I have had it stuffed and send it to you by Capt. Hughes of the Laidmans. It is in excellent preservation & I hope will reach you so. In the same package I have sent a small Box containing 37 Jamaica Land Shells many of which I believe are unknown in England & all of which may be new in your Cabinet as I understand that the collecting of them has commenced within very few years past. Another Box contains a snake skin of a large size. This was the fruit of Richard’s skill & prowess & he would have it sent. I doubt whether it will shew well by that hanging on the little Parlour.[29]

Dick’s fascination with nature had stayed with him since childhood, and he was sometimes assisted in his explorations by a ‘faithful & good servant’ called William. ‘I have collected a pretty good lot of Insects chiefly Butterflies which will be forwarded by the Laidmans next trip,’ Dick wrote to Aunt Jane on another occasion. ‘It was William’s proposition to collect them & send them as he was very anxious to make some humble return for your great kindness to him after poor Isaac’s death.’[30] To return to an earlier line of speculation, I wondered whether this ‘William’ to whom Jane had shown such kindness was the same ‘William Robertson’ who was named on George’s compensation form?

FROM HOBART TOWN in Van Diemen’s Land, John Dobson sat down to write to Dick, his brother-in-law, on 30 March 1837. His letter opened with the joyful news that Mary Ann had just given birth to their fourth child: ‘They are both doing well, & I suppose we have a good chance of having at least a dozen, the more the merrier say I, especially in a land where they are wanted. I trust you are rapidly making your fortune, if not, pray come here, & turn Wool Grower, instead of a Sugar Planter.’

Here John paused, picking up his pen again three days later: ‘I had written thus far, the happiest of men, & now alas I am the most miserable.’ That morning, John had visited Mary Ann in her bedroom before going down for breakfast; moments later he heard a loud thump on the floor above. Mary Ann had climbed out of bed, the footstool on to which she stepped had slipped, and she had banged her head, dying instantly. ‘I don’t know what to think or what to say,’ John continued. ‘Who now can ever bring up our dear children with the same gentleness & affection as their sainted Mother, surrounded too by convict Servants I cannot bear to think of it. I write in a hurry dearest Richard to save the next ship, the last for some weeks. I must write – yet I feel stupefied with horror, & with amazement, & with Grief – I wish I was dead too.’[31]

John’s letter reached Dick in Jamaica, via England, six months after the sad event it describes. A letter from Aunt Jane arrived by the same ship. Dick’s reply to her reveals his distress. Not only had he been extremely close to his sister Mary Ann, but his brother George recently seemed to have forgotten about his existence: ‘It is two years since I have received a line from him, & during that time I have written him repeatedly; however I suppose the Balls and gaities of Newcastle entirely drive from him the recollection of a Brother so far removed from him. My Dear Aunt if this rambling letter appear to be written peevishly or in an illnatured strain you must excuse it as my spirits are not of the most buoyant description.’[32]

WITH FLAWED OPTIMISM, the British government had imagined the ‘apprenticeship’ as a time when former slaves might acquire the industrious habits of free citizens, and former slave owners might adapt their businesses to the demands of a wage economy. But many planters – perceiving this to be their last chance to exploit their former human property – refused to let apprentices take days off to which they were entitled, withdrew their supplies of food and medicine, and packed wayward individuals off to ‘dance’ the treadmill at the local house of correction.

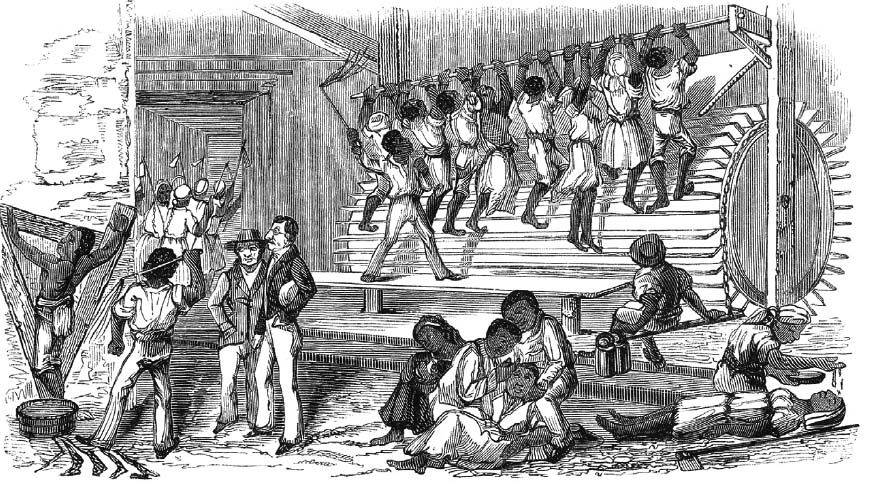

Cousin George Atkinson had been the sponsor of the legislation to introduce the treadmill, also known as the ‘everlasting staircase’, which the Jamaican House of Assembly in 1827 approved for use ‘in lieu of imprisonment in the workhouse, committal to hard labour, or flagellation’.[33] A treadmill might keep ‘upwards of 20 prisoners’ occupied in the ‘grinding of Corn, pumping of Water, or any other purpose where power is required’; it comprised a large, horizontal wooden cylinder attached to an iron frame, with shallow steps and a handrail to which wrists were strapped.[34] Stepping on to the cylinder caused it to rotate; as it gained momentum, the prisoners were forced to ‘dance’ ever more nimbly, while an overseer lashed them from behind. The ground below the treadmill was invariably sodden with blood.

The treadmill, or everlasting staircase.

Eighteen months into the ‘apprenticeship’, a parliamentary committee was set up to look into allegations of the excessive use of corporal punishment by the Jamaican magistracy. Towards the end of 1836, the Quaker philanthropist Joseph Sturge embarked with three colleagues on a tour of the West Indies. In Jamaica, they came across a boy who had recently suffered seven continuous days on the treadmill at Half Way Tree workhouse. ‘His clothes had been flogged to pieces there. His chest was sore from rubbing against the mill, and he is still scarcely able to walk from the effects of an injury in the knee, inflicted by the revolving wheel, when he lost the step,’ Sturge wrote in his bestselling account of the expedition.[35] The first-hand testimony of James Williams, a young man brought back by Sturge from Jamaica, would also generate a great deal of publicity. Williams’ description of the brutalities to which he and his fellow apprentices had been subjected was another reminder that the task of abolition was not yet completed.

The committee was to prove a toothless body; but soon the government could no longer ignore the clamour of the British public against the ‘apprenticeship’. On 11 April 1838, less than four months before the first, ‘non-praedial’ category of former slaves was due to be emancipated, parliament passed a bill to amend the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833. Henceforth, the travel time to and from the apprentices’ places of work would be included within the forty hours and thirty minutes of free labour they were compelled to give their former owners each week; the punishment of female apprentices through the treadmill, flogging, or ‘cutting off her Hair’, was prohibited; and apprentices who were cruelly treated could be freed early.[36] But ultimately it was a ruling by the Law Officers that brought the matter to a head. They directed that apprentices employed as mechanics on estates should be reclassified as ‘non-praedial’, even if they performed occasional field labour; this would qualify them for liberty two years earlier than their ‘praedial’ co-workers. Without these skilled men, the manufacture of sugar would be practically impossible. Left with little choice, the Jamaican House of Assembly voted to end the ‘apprenticeship’ in its entirety from 1 August 1838.

Beneficent Britannia bestows liberty upon an African family.

Wilberforce House, Hull City Museums and Art Galleries/Bridgeman Images

On 31 July, as midnight approached, many men, women and children climbed to the hilltops in anticipation of the most richly symbolic sunrise of their lives. The following morning, on the steps under the portico of the King’s House in Spanish Town, the governor Sir Lionel Smith declared the end of slavery to a rapturous crowd. All those who had grimly predicted rivers of blood were yet again proved wrong; the day passed peacefully, marked by services of thanksgiving and scenes of joyous feasting.