TWENTY-THREE

![]()

Farewell to Jamaica

AT THIS POINT, I hope you won’t mind briefly visiting Temple Sowerby with me, in order to tie up an important loose end. Cousin Matthew Atkinson, whose father Matthew had died in 1789, has played a peripheral role in this saga; for while they were beneficiaries of their uncle Richard’s will, he and his younger brothers wisely stayed away from Jamaica, and kept out of the feud which divided their aunt Bridget’s branch of the family. Even so, I owe Matthew a debt of gratitude, since it was through him that I stumbled upon this story in the first place – for it was a cardboard box of his letters that my sister and I inherited, and which I spent many weeks deciphering, all the while believing them to be addressed to my direct ancestor Matt.

Although these first cousins shared a name, and enjoyed fishing together, they were cut from very different cloth. Industrious Matthew (as opposed to indolent Matt) had followed his father into the business of banking; he was a stalwart of the local magistrates’ bench, three times Mayor of Appleby, and High Sheriff of Westmorland. The fortunes of Matthew’s Penrith Bank had started to sink following the stock market crash of 1825, when optimistic speculation in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars peaked, then collapsed; and in February 1826 he was forced to go cap in hand to Lord Lonsdale, the local grandee, who agreed to guarantee him ‘to the extent of £10,000’.[1]

By 1837, after a turbulent decade during which he was never far from the abyss, Matthew had decided to retire. ‘I rejoice to hear that you have determined to wind up your Banking concerns,’ John Clayton wrote to his older cousin. ‘I always thought that you carried them on more for the Benefit of others, than of Yourself.’[2] But all Matthew’s efforts over the next few years to merge his business with another more stable operation would come to nothing; more than thirty privately owned banks toppled during the ‘dark and heavy period’ which began in mid-1840, and the Penrith Bank was one of the first to fall.[3] Matthew was declared bankrupt on 15 September. ‘Death would be more welcome to me a thousand times than a forfeiture of honor & Integrity,’ he had once written, and in those days there were few things more discreditable than financial ruin.[4]

On 25 March 1841, Matthew’s Temple Sowerby residence – The Grange – and his farms were sold by auction at the Crown Hotel in Penrith, raising £26,200 towards his debts.[5] (Cousin George Atkinson, with a view to retiring there from Jamaica, made an unsuccessful bid on the house.) Matthew was meanwhile in France, evading arrest; his accomplice in planning his escape had been his cousin Jane Atkinson. She was now in her mid-sixties, her eyesight was poor, and she rarely left the village; during that winter, however, she started sending her coach out regularly, so that it became a familiar sight around the neighbourhood. Then, one night, Matthew took flight in it. Jane also arranged for his private papers to be taken to her house for safe keeping – which is how they came, circuitously, to be in my possession.

VARIOUS FACTORS WOULD conspire to drive the planters of Jamaica to the brink of collapse during the 1840s, the most obvious being the rupture to the labour supply that occurred at the stroke of midnight on 1 August 1838. Sugar cane was a demanding crop, requiring a large, disciplined workforce, and most newly liberated men and women chose no longer to toil in the fields of their former masters. Many planters tried to hold on to their workforce by imposing coercive contracts that linked the continued occupation of huts and provision grounds to compulsory labour, and when their former slaves refused to submit to such terms, some landowners responded by demolishing settlements, slaughtering livestock and chopping down breadfruit trees. These clashes caused an exodus from estates throughout the island.

Many evicted families squatted on vacant land, of which there was plenty; the more enterprising saved money to purchase smallholdings, often from debt-ridden planters selling off plots for as little as £2 per acre. Within a few years of abolition, however, the standard charge of a day’s wages as weekly rent for housing, and the same for the use of provision grounds, had been established around the island. The principle that no planter could force his tenants to work for him was also widely accepted; they were free to work for whomsoever they wished.

Cousin George Atkinson sailed back to Jamaica in January 1840 after spending nearly a year in England, much of it with Aunt Jane at Temple Sowerby, recovering from an accident that would cause him to ‘hobble sadly’ for the rest of his life.[6] On his return, he was relieved to find March’s Pen, his property near Spanish Town, in good order. ‘My Farm here has suffered some what by my absence though not more perhaps than from so great a change as the Emancipation might be expected,’ he told Jane. ‘I found my house here as if I had been absent only for one of my usual three weeks planter rounds – and that not one of my people had left me for Freedom or any other cause which is very gratifying. In fact I must say I doubt whether any body of people would on the whole have behaved themselves so well under such a change as my dingy Country folks have done.’[7]

A visitor to Jamaica, the Quaker minister Joseph John Gurney, attended a dinner hosted by George in March 1840, and observed the optimism of his fellow guests: ‘These men of business take a hopeful view of the improved condition of affairs within the last few months, and appear to look forward, on substantial grounds, to the future prosperity of the colony.’[8] Many planters embraced agricultural machinery for the first time, having previously shown little interest in it. (The enslaved workers who were needed in large numbers to process the cane during the intensive crop period had always been relatively under-employed during the quieter months, when planting and weeding took place; the plough and harrow would only have made them even less busy.) The planters also looked to new fertilizers to revitalize their exhausted cane fields. ‘You should try the Guano on your light Temple Sowerby soil,’ George advised Aunt Jane. ‘I am satisfied you would find it answer.’[9]

In the end, it was not the labour shortage, but a radical change of economic policy, that sounded the death knell for the Jamaican plantation system. The old imperial model of trade dating back to the Navigation Acts of the 1650s, which through preferential tariffs protected British goods and produce against foreign imports, and restricted the traffic between the mother country and her colonies to British-owned ships, now felt insular and outmoded; meanwhile British consumers were fed up with the prohibitively high prices that arose from stifled competition. For many manufacturers, merchants and shipowners, the adoption of free trade had become a burning cause.

In their shared opposition to the principles of free trade being applied to sugar, the West Indian and anti-slavery lobbies enjoyed the strange sensation of being on the same side, for perhaps the first and last time. Certainly, Joseph John Gurney shuddered at the thought of cutting import duties on foreign sugar. He told his brother-in-law, the abolitionist Thomas Fowell Buxton:

A market of immense magnitude would immediately be opened for the produce of the slave labor of the Brazils, Cuba, and Porto Rico. The consequence would be, that ruin would soon overtake the planters of our West Indian colonies, and our free negroes would be deprived of their principal means of obtaining an honorable and comfortable livelihood; but far more extensive, far more deplorable, would be the effect of such a change, on the millions of Africa. A vast new impulse would be given to slave labor, and therefore to the slave trade.[10]

Dick Atkinson became a partner in the Kingston house from 1 January 1844, despite his older cousin’s reservations about his temperament. ‘I do wish he had more activity of mind and really would give himself more to Business,’ George wrote to Aunt Jane. ‘I know he thinks me very savage in my attacks on him but my only motive has been to rouse him and to prevent his falling into that apathy and careless fashion which in my Uncle Matthew caused such serious injury to my Father’s House.’[11] While advocates of free trade made political headway at Westminster, commercial confidence ebbed away in the West Indies. ‘Business is extremely dull here and I think if War was declared, it would do us good, at all events in these dull times we should have something to talk about,’ Dick wrote home in October 1844.[12]

During the early 1840s, the Conservative prime minister Sir Robert Peel would abolish or cut more than a thousand tariffs, including those on cotton, linen and wool, replacing lost revenues with a new 3 per cent income tax. ‘There hardly remains any raw material imported from other countries, on which the duty has not been reduced,’ he declared in January 1846.[13] Peel made an exception for sugar, though, arguing that it should be ‘wholly exempt’ from the principle of free trade, since to give slave-grown sugar unfettered access to the British marketplace would mean ‘tarnishing for ever’ the national achievement in abolishing slavery.[14] He also wavered about grain. The Corn Laws had been passed in 1815, to prevent cheap continental grain from undercutting the homegrown product; but they also propped up the landed gentry at the expense of both the urban poor, who endured the high cost of bread, and industrial magnates, who needed the rural peasantry to be freed from the fields to provide labour for their factories and mills. Peel had repeatedly voted against repealing the Corn Laws, but the poor harvest of 1845 and the devastating famine in Ireland made him change his mind. In June 1846, Peel won the repeal of the statutes in the teeth of fierce opposition from protectionists within his own party. They would punish him for this victory, however, by instantly forcing his resignation.

Lord John Russell, a Liberal, followed Peel into office; by August 1846, he had carried the Sugar Duties Act through parliament. The duty on all foreign sugar would drop with immediate effect to 21s per hundredweight and fall incrementally each year for the following five years, until all sugar entering British ports was taxed equally. The effect of this legislation upon the Jamaican economy was cataclysmic. West India merchants in London suddenly stopped offering credit, to the distress of their clients who purchased estate necessaries every autumn with money advanced against the forthcoming sugar crop. A programme to ease the labour deficit in Jamaica by bringing indentured ‘hill coolies’ from India – the first ship had arrived from Calcutta in May 1845 – was instantly suspended. The planters saw the Sugar Duties Act as a profound betrayal, an act of heedless vandalism.

GEORGE ATKINSON RETIRED from the Kingston house at the end of 1846 – he was fifty-one – leaving Dick and another partner, Charles MacGregor, to take over the business. After twelve years under the thumb of his domineering cousin, Dick found the new set-up infinitely more congenial. As he told Aunt Jane, in a sentence that speaks volumes about his opinion of George: ‘Let times be ever so bad, and our work ever so laborious, I have the satisfaction of being joined in Copartnership with an honest, good man, and who places the same confidence in me, as I should always do in him, allowing us, altho’ not making money as former Firms did, to enjoy happiness, free from all suspicion of one another, and living on good terms with all our neighbours.’[15]

After the Sugar Duties Act passed into law, mercantile business more or less dried up in Jamaica. Atkinson & MacGregor’s most flourishing concern was their flour mill and bakery, which produced ‘excellent Bread’ and hard, dry ‘Sea Biscuits’ for the navy – ‘100 puncheons of 346 lbs. each, per week’ – but this barely kept one of the partners busy, let alone both of them.[16] With estates everywhere being sold off cheap, often for one-twentieth of the price they might once have commanded, Dick turned to property speculation. John Clayton’s law firm handled his purchase of the Lloyds, Coldstream and Mount Sinai estates in the parish of St David, subdividing the properties so that they might be sold off as small ‘parcels of Land’.[17]

A bumper sugar crop in 1847 caused an oversupply that wiped more than a third off the London wholesale price of sugar, and bankrupted thirteen merchant houses dealing with the West Indies. Not only was British free-grown sugar more expensive to produce than the foreign slave-grown variety; it also cost twice as much to carry it across the Atlantic, on account of the Navigation Acts. Dick wrote to brother George on 7 September:

The Colonies have been, and continue to be most unjustly treated. Why did not they grant the same free trade to us, as the Slave colony of Cuba enjoys. Why not let us get an American, German, Prussian, or Sardinian vessel to take our Produce to market at the rate of 2s. to 2s. 6d. per ½ ton – instead of paying a British vessel 5s. & 6s. per ½ ton – if the Tories have been unable to stop the very sweeping free Trade views of the Rads, they should fully & fairly for better or worse carry out the meaning of free trade – attack the navigation laws, and let us, and all the British Possessions look to the cheapest market they can find for their shipping.[18]

The Navigation Acts would finally be repealed in 1849, opening up the imperial trade to the vessels of any country.

The plunging price of sugar soon finished off many plantations. ‘A great number of Estates are entirely abandoned – and others are following from the necessary supplies of money being stopped,’ Dick wrote in November 1847. ‘I am continuing the cultivation of Lloyds & Mt Sinai in the hopes of better times – but I must say I often think I am wrong in so doing.’[19]

Dick would hold his nerve a few more years; in October 1849 he paid £800 for the 1,400-acre Norris estate, located a few miles from his other properties in St David Parish.[20] Often, when he wished to escape the suffocating heat of Kingston, he would ride out to his ‘pretty little House’ at Mount Sinai in the ‘certainty of enjoying a cool Bed’; the cottage nestled on the banks of the mighty Yallahs River, with views across to the Judgement Cliff, the site of a massive landslide during the fabled earthquake of 1692. ‘A few days there, bathing regularly, set me up wonderfully,’ Dick wrote.[21]

These days, in contrast to its past reputation as a tropical graveyard, Jamaica was considered a salubrious place to visit. Dick’s younger sister, Jane, spent the winter of 1848 on the island; he had urged her to come out for the benefit of her delicate constitution. The physician Robert Scoresby-Jackson – an expert on the effects of climate upon health – stayed with Dick around this time, and was much struck by the range in temperatures to be found in Jamaica:

In the middle of May I left the hospitable mansion of Mr. Atkinson at 6 a.m., after a restless and feverish night on the plain of Liguanea, and at noon, under the guidance of a kind friend, reached Pleasant Hill, part of the journey having been performed in a carriage, and the remainder on mules, over narrow mountain roads, down steep declivities, across the rapid Yallahs River, and amid grand, picturesque, and ever varying scenery. The change of climate was delicious, the air cool, fragrant with the white and red rose, and perfumed with the orange blossom. On the Liguanea Plain, during the previous night, the lightest covering had been scarcely bearable, yet at Pleasant Hill a couple of blankets were agreeable.[22]

Dick must have made this trip countless times, for Pleasant Hill, in the Port Royal Mountains, was a property he managed. But I’m not sure he would have described it quite so evocatively – by his own admission, he was notorious for ‘writing stupid letters’.[23]

ABOUT DICK’S COURTSHIP of Elizabeth Pitter, I know nothing – on matters of the heart his letters are silent – but they married in May 1849, when he was thirty-six and she was twenty-one. It is possible that they met through Dick’s planter friend William Georges, who was married to Eliza’s older sister Julia. The Pitter sisters were sixth-generation Jamaicans, descended through their paternal grandmother from Richard James, an officer on the buccaneering Penn and Venables expedition which had seized the colony from the Spanish in 1655; their three-times great-grandfather was said to have been the first white man born of English parentage on the island.

In July 1851, Dick, Eliza and their two infant children boarded the Medway, one of the speedy new Royal Mail steam vessels which had cut the passage time between England and the West Indies to just three weeks. Its captain, William Symons, was Dick’s brother-in-law. Jane Atkinson had married Symons within months of her return from overwintering in Jamaica three years earlier – I imagine she must have met her husband on board his ship.

The Medway arrived at Southampton on 20 August; Jane and her baby son were waiting to greet the party. Before heading north, Dick and Eliza were delayed a week while they recruited a new nursemaid. ‘I brought one from Jamaica, a colored Woman, but she will not do for this Country, I must send her back,’ Dick told Aunt Jane. On their way through London, he and Eliza visited that triumphalist celebration of global free trade, the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park. Out of thousands of goods representing every permutation of human ingenuity – from the electric telegraph and an unpickable lock to papier-mâché furniture and a bust of Queen Victoria carved from soap – Jamaica had offered one meagre contribution, a display of artificial flowers made from the fibre of the yucca plant.

Dick planned to spend a year in England, but was not yet sure where to base his family: ‘This is a puzzle that often perplexes me, I do not like Newcastle or the neighbourhood, the Lake district, or the vicinity of Liverpool might suit me, the former I am so fond of, and in the latter there are so many Friends.’[24] At his aunt Wordsworth’s house near Liverpool, Dick met up with brother George and their cousin Bolton Littledale, and the three men immediately set out on a fishing expedition. Surrounded by close relatives, with a rod in his hand, Dick was reminded of all that he had missed during nearly twenty years’ absence from England; next time he brought the family home, he resolved, it would be for good. ‘The recollection of the few unhappy years, of constant craving after wealth, that both my cousin George & Mr. Hozier exhibited – is quite sufficient reason for me to drop Business – while I yet have constitution & strength of mind to do so,’ he told Aunt Jane. ‘Neither the Wife or self have extravagant tastes, and as to the children we must just bring them up to suit my Fortune.’[25]

When Dick and Eliza returned to Jamaica, at the end of 1852, it felt more like a backwater than ever. Everywhere, bush scrambled across the neglected fields of once-flourishing plantations – a total of 316 properties, or nearly half the island’s sugar estates, would be abandoned between 1834 and 1854.[26] Kingston was in large parts a slum, with ‘lean, mangy hogs’ and ‘half-starved dogs’ scavenging its unpaved, rubbish-strewn streets.[27] ‘Jamaica, the oldest colony of the British crown, presents the most extraordinary spectacle of desolation and decay the world ever witnessed,’ commented one former resident. ‘It now lies helpless and ruined by the policy of the mother-country, that should have fostered its resources, and smoothed its difficulties, during a transition of no ordinary nature.’[28] Meanwhile, the island’s northern neighbour continued to welcome slave ships into its ports: ‘Cuba is prosperous, and red with the blood of the African, she has splendid cities, quays, and wharfs, long lines of railroads, an unexceptionable opera, costly equipages, and every luxury worthy of the first capitals in Europe, and instead of borrowing money from the mother country she sends home a princely revenue.’[29]

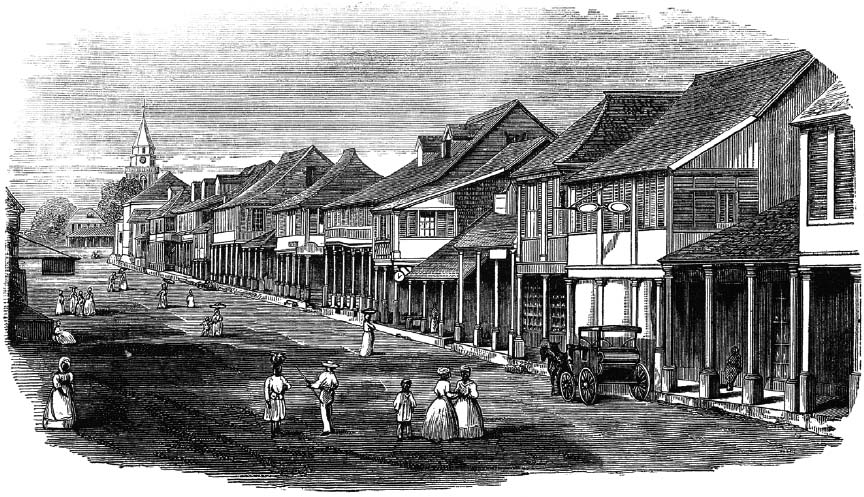

Kingston in the 1850s, looking up King Street towards the parish church.

It was Aunt Jane’s death in March 1855, a week after she turned eighty, that ultimately prompted Dick’s decision to quit Jamaica. In her will, Jane divided her possessions unequally among her nieces and nephews. To Dick, for example, she left £1,000; to her brother George’s children, whom she considered quite wealthy enough, she gave nineteen guineas apiece. To Sarah and Anne Clayton, she left her furniture, plate, linen, china, books, prints, pictures and wine, and to Sarah alone she gave her shells and coins. Temple Sowerby House, her farms and portfolio of property in the village passed to her executor, John Clayton; the gossip on the Atkinson side of the family was that Aunt Jane had borrowed so much money from her rich nephew that it would all have gone in his direction, whether she had bequeathed it to him or not.

To cut a long story short, John Clayton agreed to let Temple Sowerby House to Dick for the cousinly rate of £45 a year. On 27 April 1856, as heavy rains turned the streets of Kingston into ‘formidable rivers’, Dick, Eliza and their three young children climbed aboard the Parana, and waved farewell to Jamaica for the very last time.[30]

DICK AND ELIZA moved into the ancestral home in July 1856. They found it emptier than it had been in Aunt Jane’s day; only the largest, shabbiest pieces of furniture remained, unclaimed by the Clayton sisters to whom they had been left. My great-grandfather John Nathaniel (known as Jock) was born in May 1857, and four more babies would follow, bringing the final tally of children to eight; with a governess and six servants also living under the same roof, it was a busy household.

Although he was just forty-three when he returned to England, Dick would trouble himself no further with business; henceforth the family would live off the income from his investments, mostly in American railroad stocks floated by Barings. He cut the last of his financial ties to Jamaica in 1861, with the sale of the Norris estate to his brother-in-law William Georges for just £500. Apart from Lizzy, their eldest daughter, none of Dick and Eliza’s offspring grew up with memories of the colony; it must have seemed a fabled place, represented by their mother’s lilting accent, and the wooden cases of crystallized tropical fruits their parents sometimes had shipped over as a treat.

From now on, the flow of family correspondence declines to a trickle, which means that I must rely upon the pocket diaries in which Dick diligently recorded the events of his uneventful rural existence. Nineteen of these slim volumes, one accounting for each of his remaining years, are stacked up on the desk before me. Snowdrops in January, pruning fruit trees in February, potting geraniums in March, the first cuckoo in April, swarming bees in May, haymaking in July, the first snow settling on Cross Fell in October, the slaughter of the pig in November – the seasons beat the same rhythm every year. Most days, except Sundays, Dick devoted at least an hour or two to field sports; he kept a note of his bag, and if you were to tot up all the hares, rabbits, grouse, partridges, pheasants, pigeons, snipe, woodcock, chub, salmon and trout that perished at his hands, the number would run into tens of thousands. Apart from twice-yearly fishing and shooting expeditions to Loch Awe in the Scottish Highlands, where cousin Bolton Littledale owned a hunting lodge, Dick and Eliza rarely strayed from hearth and home; dinner with neighbours at Acorn Bank or Newbiggin Hall, barely a mile away, was almost as far as their social lives took them.

AFTER THREE DECADES as town clerk, John Clayton remained the most powerful man in Newcastle – ‘like the Sphynx in the desert,’ wrote a journalist, ‘while the sands of time sweep round his feet.’[31] Under his watch, the town had been transformed from an old-fashioned place, criss-crossed by winding alleys and tightly enclosed within medieval walls, into a modern metropolis, the clanking heart of the industrial revolution. On a twelve-acre greenfield site, formerly the grounds of an ancient manor house, an elegant new town centre had been built from scratch, masterminded by the developer Richard Grainger; its principal thoroughfares were named Clayton Street, Grainger Street and (in honour of the great Northumbrian architect of parliamentary reform) Grey Street.

Grey’s Monument, at the heart of Newcastle’s magnificent new town centre.

© British Library Board. All Rights Reserved/Bridgeman Images

But for John Clayton’s support, the scheme might easily have collapsed. Grainger was a visionary, but he was also an incorrigible speculator, who financed his developments through a complex web of mortgages and remortgages. John’s involvement undoubtedly calmed investors’ nerves; he not only acted as Grainger’s solicitor, but also lent him large sums of money. Clayton Street would be the most ‘chastely ornamented’ of the three main roads, in keeping with the sombre dignity of the legal gentleman for whom it was named; it was left to Grey Street, with its descending curve and Corinthian façades, to project the town’s swaggering confidence.[32] (John would later claim that the bend in Grey Street had been his idea, inspired by Oxford’s High Street.) By 1840, six years after the building works began, nine new streets had been completed, boasting amenities that included a new market, a grand theatre, a music hall, a lecture room, a dispensary, two chapels, two auction markets, ten inns, twelve public houses, 325 combined shops and residences, and forty private houses. ‘You walk into what has been long termed the Coal Hole of the North, and find yourself at once in a city of palaces; a fairyland of newness, brightness, and modern elegance,’ wrote one visitor, a touch breathlessly.[33]

John’s vast personal wealth, in part generated through his fees as solicitor not only to Richard Grainger, but also to the Corporation of Newcastle and the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway Company – a pile-up of interests that would be unthinkable today – did not go unnoticed by his fellow citizens. An anonymous observer wrote in 1855:

A pendulum of sovereigns – steady, round, and bright – appears always to regulate the internal machinery of the Town Clerk. It is difficult to discover more diligent success in acquiring money over a space of thirty years by the humblest, and meekest, and most common-place drudgery. Mr. John Clayton never speculated. He never threw dice. He never sunk a pit. He never founded a bank. Slow, sure, regular, and passionless – like a Laplander trudging and toiling over a waste of snow – Mr. John Clayton has pursued the even tenor of his way; but instead of his feet being clogged, like the Laplander’s with snow, they are clogged with yellow dust, unalloyed gold, of sure and most indubitable accumulation.[34]

During the week, John shared the old Clayton mansion on Westgate Street with his younger brother Matthew, his partner in the family firm, which had grown into the largest legal practice in the north of England. Both men were bachelors; indeed, only three of Nathaniel and Dorothy Clayton’s eleven children would marry, and just one, their youngest son Richard, would perpetuate the family name. Beyond his official and professional duties, John’s main recreation was the preservation of the Roman wall that stretched between the Solway Firth and the River Tyne. Locals had freely plundered the wall for its ‘well-shaped, handy-sized stones’ for as long as anyone could remember, and a passing antiquarian had been dismayed in 1801 to find John’s uncle, Henry Tulip, in the process of dismantling ninety-five yards in order to ‘erect a farm-house with the materials’.[35] John purchased his first section of the wall in 1834; he would end up owning eighteen miles, from Carvoran in the west to Planetrees in the east.

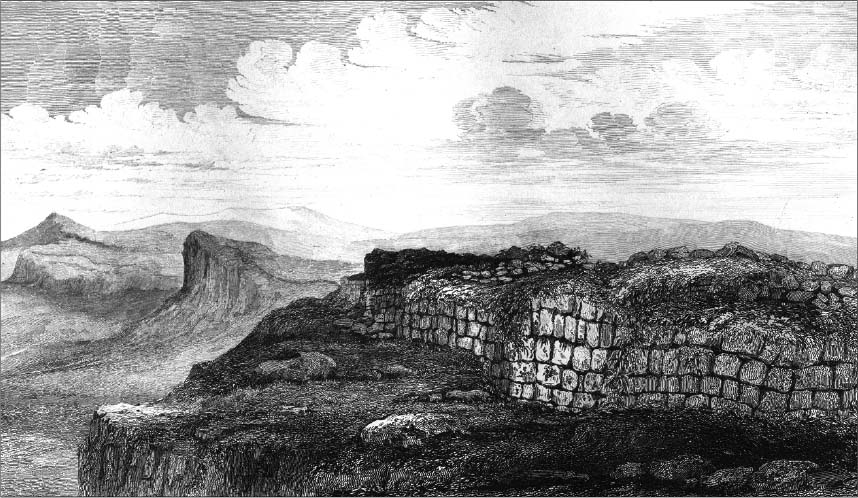

Hadrian’s Wall to the west of Housesteads, prior to its restoration by John Clayton.

John started restoring the wall in 1848, and the project would continue for more than twenty-five years. The techniques adopted by the labourers working under his supervision – he set aside Mondays for site visits – were surprisingly sensitive for the times. First they cleared the loose rubble along the sides of the wall; next they used these stones, without mortar, to build a protective skin around the exposed Roman masonry, thus preserving the original core; and finally they capped it off with turf. John also ordered the demolition of a number of farm buildings that were encroaching on the wall, and he put an end to arable farming along its path, instead introducing hardy breeds of cattle and sheep to complement the upland scenery. When people think of Hadrian’s Wall these days, they are most likely to picture the rugged scenery to the west of Housesteads, where the sturdy structure hugs the craggy Whin Sill – this is the section known to cognoscenti as the ‘Clayton Wall’.

DICK BEGAN CASTING around for occupations for his sons as they approached manhood; his pocket diary for 1872 contains several pages of closely written notes about the admissions criteria for ‘Indian Civil Engineering College’, and the salary, in rupees, that its graduates might earn. It seems likely that Dick mentioned this as a possible career for fifteen-year-old Jock when cousin Annie Clayton came to stay at Temple Sowerby in April 1873, as a few weeks later her sister Sarah, the boy’s godmother, sent a cheque for £100 to cover the cost of tutoring him for the fiercely competitive public exam to enter the Indian Civil Service.

Dick’s health began to fail shortly after his sixtieth birthday. On 5 April 1875 he went fishing, pulled two trout from the river, walked home ‘not feeling very well’, sent for the doctor, and took to his bed. His diary is almost blank from then on – a break that feels shockingly abrupt after nineteen years of assiduous record-keeping – and the few remaining examples of his handwriting are visibly feeble. During the autumn, after a moment when the family believed him to be gaining strength, Dick went into a steep decline. ‘We had him downstairs in the fishing room for an hour or two on Thursday, but he did not recognise the room and kept talking about leaving this house and going home,’ reported 21-year-old Jane on 4 December.[36] A week later Jock, who had been cramming for the India exam in London, arrived at Temple Sowerby for Christmas. ‘It is a great comfort to have him,’ wrote Jane. ‘Daddy recognised him as he does everybody at first sight, but the remembrance of people passes from him directly the first flush of recognition is over.’[37] Dick died, nine months after the onset of his illness, on 18 January 1876.

JOHN CLAYTON RETIRED from the Newcastle town clerk’s office in 1867, when he was seventy-five – he and his father having served eighty-two years between them – and subsequently devoted himself to his Roman studies. As the objects unearthed by his excavations along the wall grew into a large collection, finding space for them became an increasing challenge. A stone colonnade was built along the front of Chesters mansion to provide shelter for some of the bigger sculptural and inscribed pieces; a wooden summerhouse in the garden was also pressed into service.

John would remain active into his nineties; under his direction, a significant hoard of sculptures and altars dedicated to the war-god Mars Thincsus was found at Housesteads fort in 1883. He kept open house at Chesters, and archaeological enthusiasts often dropped by. Treadwell Walden, a visitor from Boston, called in 1886:

The servant who answered our ring took our cards and ushered us into the library – a large room, filled with books, and whose walls were covered with paintings. When Mr. Clayton was ready to receive us we found him reclining on a couch in the middle of the great room. He at once greeted us with cordial courtesy, and remarked smilingly that he had been troubled with an old enemy, the gout, and that ‘he was somewhat older than was convenient,’ but it would give him great pleasure to show us the Roman remains on his grounds, as well as those collected in the house. He then conducted us out into the broad hall, and took us from one to another of the fine figures in bas-relief that stood there, repeating to us in full the somewhat illegible and frequently missing parts of the inscriptions. We were shown, also, the smaller articles in another room. Of these there was the richest variety. There were coins, literally by the peck, enclosed in many bags, heaped upon a box.[38]

These must have been the spoils of the famous dig at Carrawburgh, ten years earlier, when John’s men had discovered the remains of a chapel dedicated to the goddess Coventina, and found a large, square well containing twenty-four altars and at least 16,000 copper coins, as well as ‘sculptures, pottery, glass, bones, rings, fibulae, dice, beads, sand, gravel, stones, wood, deers’ horns, iron implements, shoe-soles, and a due proportion of mud’.[39]

But mortality caught up with John Clayton in the end; he died on 14 July 1890, aged ninety-eight, and was buried on a stormy day in the churchyard at Warden, alongside his parents and siblings. Apart from some minor legacies – including money for the upkeep of a terrier, Marcus Aurelius – John’s fortune passed to his nephew, Nathaniel George Clayton, the eldest son of his youngest brother Richard, who inherited personal estate valued at £728,746, more than 26,000 acres in Northumberland, and twenty-two properties at Temple Sowerby, including the Atkinson house occupied by Dick’s widow Eliza and her unmarried daughter Katie.

MY GREAT-GRANDFATHER JOCK married Constance Banks in a whitewashed church in the Indian coastal town of Cocanada on 8 July 1885; at twenty-eight, he was assistant collector of Kistna district in the Madras Presidency. They had met out there, for Connie, the fifth daughter of the vicar of Doncaster, was one of those spirited young women of gentle birth – known collectively as the ‘fishing fleet’ – who had travelled to the subcontinent with the intention of catching a husband.

Connie brought their three children back to England in April 1893, settling seven-year-old George and five-year-old Jack into boarding school before taking two-year-old Biddy back to India. The following spring, in May 1894, Jock, Connie and Biddy came home again for a short vacation; the passage from Bombay, via the Suez Canal, took seventeen days. (A century earlier, the same voyage by sailing ship, round the Cape, would have lasted the best part of six months.) The whole family spent an idyllic month at Temple Sowerby. One beautiful day, Jock initiated the boys into the art of minnow fishing; by teatime Jack had cast his line all the way across the stream, a feat which earned him half a crown. Another day, Jock took the train over to Northumberland to see a second cousin, John Ridley, who lived at Walwick Hall, half a mile from Chesters; the two men strolled out to view the recent changes to the Clayton property. Since Jock’s last visit to Chesters, its new owner had commissioned the architect Norman Shaw to add wings to either side of the Georgian house, more than doubling its size. This was pure folie de grandeur, for Nathaniel and Isabel Clayton surely had no need for forty bedroooms. ‘Enormous & very ugly,’ wrote Jock in his diary. ‘Family all away.’

While old John Clayton was alive, Eliza Atkinson had enquired through his land agent whether he might sell her Temple Sowerby House; but word had come back that ‘Mr. Clayton regarded that property as the apple of his eye & wouldn’t part with it’.[40] Now Eliza and her daughter Katie found themselves in the awkward position of being poor relations to a landlord they barely knew. This must have been preying on their minds, for while Jock was passing through London, he called on Nathaniel Clayton at home in Belgrave Square in order to ascertain the status of their tenancy. The conversation lasted barely three minutes – he arrived just as his second cousin was about to go out – but the outcome was satisfactory enough. ‘N.G. Clayton assured me that he would not let the T.S. property pass from himself & the Atkinson family to outsiders,’ Jock noted.

This time, when Jock and Connie returned to India, they left all three children behind under the care of their maternal aunts. George, Jack and Biddy waved their parents goodbye at the railway station on 20 July. ‘Fortunately,’ recorded Jock, ‘their thoughts were distracted at the time: & they seemed hardly to realise it.’ The couple’s reasoning may have been sound enough – India was reckoned a dangerously unhealthy place to raise a family – but it meant they would barely know their children. In due course, the boys would follow Jock to his alma mater, Marlborough College, while Biddy attended Hendon Hall, a girls’ boarding school just north of London.

Jack, my grandfather, was called to the bar after graduating from Cambridge; but he never practised law, instead falling in with a set of rich, spoilt young men. Jack was an engaging and decorative fellow, but he lacked the funds to make a proper career of loafing around, and his father’s threats to cut off his allowance eventually took effect. In May 1914, aged twenty-six, he emigrated to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he found work as a stockbroker.

Three months after Jack’s departure, his parents came home to England, settling near Alton in Hampshire. Jock’s loyal service to the empire had ultimately been rewarded with a knighthood. The Madras Times marked his retirement with a lengthy tribute that was lavish in its faint praise: ‘You naturally look back upon the landmarks of Sir John’s service when the time comes for parting with him, and you don’t find any. And this means that he has been content with simply doing his duty. He has worked well with his equals, his superiors, and his subordinates. And this, after all is said and done, is the highest achievement possible to an Indian Civil Servant.’[41]

The Great War offered Jock and Connie a chance to rekindle their relationship with their younger son. Jack enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in December 1915; six months later, his parents bade him farewell at Folkestone as he departed for the front with the 13th Battalion Royal Highlanders of Canada. Within days, the battalion had been posted to Sanctuary Wood, a hellhole of waterlogged ditches, tree stumps and barbed wire, where it would experience the horrors of intense bombardment for the first time. Jack had the good fortune to contract trench fever in August 1916; while he was recuperating at army hospitals in Saint-Omer and Boulogne, and then with his parents in Hampshire, hundreds of his fellow men from the 13th Battalion would lose their lives in the Battle of the Somme.

Nor was Jack to be found in the main assault on Vimy Ridge in April 1917 – an action noteworthy as the first time that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought together. Instead, it was his responsibility to deal with the corpses. ‘Lieut. J.L. Atkinson is detailed to supervise the clearing of the battlefield,’ ordered the adjutant prior to the offensive. ‘He will report at Battalion Headquarters before dawn and will work in conjunction with, and under the orders of, the Divisional Burial Officer.’[42] The capture of the ridge came at enormous cost, with 3,598 dead out of 10,602 Canadian casualties. No medals for gallantry would be pinned to Jack’s chest, but the mere fact that he survived the war more than suffices for me. He would remain in France until February 1919. On the afternoon of 5 April, as the 13th Battalion was in the process of being disbanded, Jack walked up the hill behind his parents’ house and fired off the last rounds of his automatic pistol, thus concluding his military career. Four months later, he sailed back to Canada.

DURING HIS RETIREMENT YEARS in the 1920s, Jock would be struck down by what he described as a ‘violent attack of pedigree mania’ – a seemingly hereditary condition, only treatable by visits to the Public Record Office and the British Museum’s Reading Room.[43] Genealogical research became Jock’s obsession, and he poured his findings into a short ‘history of Temple Sowerby and of the Atkinson family’ in which, surprisingly, he did not once mention Jamaica – the family’s activities there being a subject about which he was curiously ignorant. (‘Have you among your papers got any information about Matthew?’ he would ask a cousin about their common ancestor, Matthew Atkinson, who had died in 1756. ‘I wonder did he ever go to Jamaica? His son Richard made a large fortune there, & at least one of his nephews went out.’)[44] At Jock’s request, Isabel Clayton, his second cousin’s widow, trawled the library at Chesters, hunting for heraldic clues in volumes which had once been shelved at Temple Sowerby: ‘The schoolmaster who dusts the books for me at present was here yesterday evening & we had a good search for a Crest, or arms, in a book plate of Bridget Atkinson – a great Number of books with Bridget Atkinson written at the beginning but never a sign of there ever having been a Crest.’[45]

Isabel Clayton died in April 1928, and the Chesters estate skipped a generation, passing to her 26-year-old grandson. Jack Clayton had been raised at Newmarket, where his late father kept racehorses, and he mixed with a fast, careless crowd; he soon resolved, having run up vast gambling debts, to liquidate his entire inheritance. First to go under the hammer, in a lively auction held at Newcastle’s Assembly Rooms in June 1929, were 20,000 acres of agricultural land, broken up into 112 lots, including ‘many capital hill farms’ straddling Hadrian’s Wall.[46] Housesteads Farm was one of the few lots that failed to reach its reserve; potential buyers were put off by the burden of maintaining the Roman fort that came with it. The eminent historian George Trevelyan, whose family owned nearby Wallington Hall, shortly afterwards agreed to purchase the farm minus the fort, on condition that Jack donated this, plus a stretch of adjoining Roman wall, to the National Trust. The Times reported ‘Mr. J.M. Clayton’s Gift’ of Housesteads Fort in glowing terms – but the evidence suggests that Jack was a reluctant donor, and was more or less shamed into this act of philanthropy.[47]

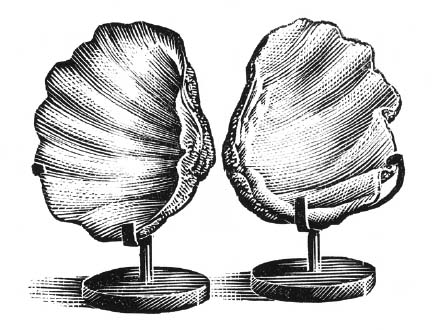

The disposal of the mansion at Chesters was immediately followed by the dispersal of its contents – ‘one of the great displenishing sales that has been held on the Borders in living memory’, said the Hexham Courant.[48] The auction began on 6 January 1930; the eighth and final day saw the clearance of the library and the scattering of more than six thousand books, among them Moxon’s English Housewifery (1764), Johnson’s Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775), Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1781), Cook’s Voyages (1784), Dixon’s North-West Coast of America (1789), Bligh’s Voyage to the South Sea (1792), Edwards’ Survey of Saint Domingo (1801) and Perry’s Conchology, or the Natural History of Shells (1811). These titles are so redolent of the life and times of Bridget Atkinson that I can only imagine they must once have belonged to her. I wonder where they are now.

A giant clam shell, all that remains of Bridget’s shell collection, now in the museum attached to the Roman fort at Chesters.

Andrew Davidson

THE LAST DECADE of Jock’s life was blighted by problems with his heart, and chest pains often followed the most trivial exertion, as per this diary entry: ‘Chastised dog for getting on drawing room sofa, & in consequence suffered much discomfort for a short time.’[49] He died at home in Hampshire in March 1931, aged seventy-three. Jock’s unmarried youngest sister, Katie, died ten months later; she had lived at Temple Sowerby all her life. Following her funeral, Katie’s executors spent two days sorting through heaps of old papers, many of which ended up on a bonfire in the garden.

The ancestral house was sold by auction at the Tufton Arms in Appleby on 27 August 1932. Everyone had expected it to leave the family for ever, but one of Dick and Eliza’s grandsons – Kenneth Kay, the son of their daughter Jane – bought the property in anticipation of his retirement from the textiles business in Madras. The proceeds of the sale, of course, lined the pockets of Jack Clayton, whose ‘bold betting’ had recently been generating what the Sunday Times described as a ‘good deal of animation in the rings’.[50]

Meanwhile my grandfather, Jack Atkinson, was working as a journalist on the Montreal Star. He married my Canadian grandmother, Evelyn Hay de Castañeda, in Quebec on 30 April 1930. (A musical, cosmopolitan woman, she had already been widowed twice; her second husband was Secretary of the Spanish Legation in Tangier.) Jack’s inheritance prospects improved markedly after the sudden death of his elder brother George, a railway engineer in India, in September 1932. He returned with Evelyn to England the following year and they set up home in London; John, their only child, was born in March 1934. When Jack’s mother Connie died, in June 1947, he inherited a life interest in the small farm that his father had purchased at Temple Sowerby. At the invitation of Kenneth Kay’s widow, Dorothy, who was living alone in the old house, Jack, Evelyn and John moved up to Westmorland that same year. When Dorothy died, in April 1955, she left the property to Jack.

In January 1957, Jack took delivery of a parcel from a second cousin, Dick Atkinson, containing bundles of papers spared the bonfire by Aunt Katie’s executors twenty-five years earlier. ‘I had hoped that I might have brought them over to you, but the petrol position forbids doing this,’ Dick wrote from his home near Newcastle. (Fuel rationing was then in place, following the Suez Crisis.) ‘I don’t envy you your job of going over all these letters, I have looked through some of them & I wonder why they were preserved, there are very few that are of much interest.’[51]

This was the box full of old correspondence that my sister and I would inherit nearly twenty years later, and which would remain untouched for a further thirty years, until I was ready to embark on my long journey into the past.