4

Know-how in Clinical Practice: Doxa as the Result of Impotence and Impossibility

INTRODUCTION

A completely comprehensive theory, supported by an effective epistemology, would seem to be an illusion. Nevertheless, Candide must continue to cultivate his garden (translator’s note: as in the final pages of Voltaire’s Candide). Clearly, for the field worker, job satisfaction in itself is not enough: her work must also be conceptually grounded, which is why she scours the markets seeking the definitive scientific justification for her job.

Such “definitiveness” quickly becomes relative, and yesterday’s certainties have become today’s cast-offs. For a growing number of people the ensuing doubt is barely tolerable. Consequently, we see the emergence of a highly characteristic solution, which was anticipated and critiqued as long ago as Socrates: if epistèmè (knowledge) is unable to found arètè (truth), people fall back on doxa (opinion), or in today’s terms “paradigm.” We have already seen this in Kuhn (1970), who re-introduced these ideas into contemporary terminology.

The contextualizing paradigm’s real function, apparently, is to guide. Depending on which psychological theory is chosen, one intervenes in x or y manner. Still, as the years go on, it is becoming increasingly clear to me that the most divergent paradigms do not necessarily lead to particularly divergent practices. Indeed, in a number of cases, such practices proved profoundly monotonous, compared to the raucous ways the various doxa competed with one another. Presently we will see how even what seem to be diametrically opposite paradigms ultimately amount to the same thing, particularly when it comes to their mutual disdain for the subject.

In other words, the paradigm’s function is not, after all, to guide a practice, whatever people might say. It has recently become increasingly clear that the effective factors in therapeutic practice are very much the same, beyond and above the various different paradigms. Every theoretically based clinical practice (psychoanalytic, cognitive behavioral, systemic, experiential…) has its good and bad therapists, and this evidently has less to do with the particular theory than with the way these therapists are (un-)able to handle these common factors. No, the paradigm’s real function is to create nest warmth, that is to say, to offer an articulated and hence security-providing framework for its followers, collected around a central credo that supplies a comforting answer to the ever-threatening Real of the clinic. We will subsequently see how this framework only incidentally influences clinical practice, and that these influences are not as diverse as one might imagine.

What we might call the “props” of these doxa can be very large or quite limited. Because of their small size, the smaller ones immediately reveal what is involved. A quick, if ironic recital gives us the Exemplary Case, the Latest One-Hit Wonder and the Guilt-tripping Drama Queen. In practice these three are frequently found in combination with each other such as, for example, every Latest One-Hit Wonder also contains a Guilt-tripping aspect as well, and an Exemplary Case is always useful to have on hand.

Exemplary Case Paradigms

Exemplary case paradigms are all those famous, if not infamous, case studies that are perpetually being rehearsed within certain circles. A quick glance back shows how every clinical master had one or even several star patients: for Charcot, it was Blanche Wittman; for Janet, Madeleine and Nadia took center stage; Flournoy chose Hélène Smith; Jung had Helene Preiswerk, and for Binswanger it was Ellen West; Mary Barnes performed the role for the Kingsley Hall Therapeutic community…The list is endless, and as a final example, we offer Freud’s own five case studies (see Ellenberger 1970, pp. 891–893, and Maleval 1984, p. 112).

Beyond this, it is an open secret that the principal patient of each of these great figures was himself. The exemplary, or any rate first case of this is to be found in Robert Burton, with his Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). Even Pavlov only came to the study of psychiatry after a so-called heart neurosis (Ellenberger 1970, p. 850). Freud himself begins from the same point as any student of the humanities: everyone always looks first for him- or herself in the array of theories, but this more or less always fails. Despite whatever his masters told him, and everything that was written in the textbooks, Freud, with his problematic train phobias and hypochondriac complaints, was unable to recognize himself. All that was left was to start looking for his own subject, Sigmund. That his patients aided him in his search is known by everyone in clinical practice. Hence, from Studies on Hysteria to The Interpretation of Dreams and The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, we get the story of a journey of discovery through the continent called Sigmund Freud. That he, and a number of other major figures, was able to go beyond this starting point and to elevate it into a theory is precisely why they are major figures. Ellenberger talks about “creative illness” and makes the inescapable comparison with the shaman (pp. 888–891 and passim).

The heroic historical narratives prefer to pass over this aspect in silence, instead presenting an image of an isolated toiler, neglecting wife and children and inventing earth-shattering theories for starvation wages while producing a number of unforgettable standard case-studies along the way.1 Their paradigmatic effect can be seen in the way the second generation, that of the master’s students, is unable to produce its own case studies perpetually returning to those of the master’s, which are then deemed classics. To give an example, it is very difficult to find a psychoanalytic study or clinical demonstration of a psychotic patient who is not constantly being compared with Schreber. It almost seems as if every modern-day psychotic has to model himself according to the near perfect Schreber-profile, whose case thus comes to function as a kind of clinical bed of Procrustes.2 Originally these case studies introduced innovative conceptual and pragmatic insights; now they have become standard weights obstructing every change.

What I call the Latest One-Hit Wonders start out from the idea that simplicity is the primary attribute of truth, and that anything can be explained on the basis of a limited etiology. Treffers (1988) likens this to a traveling circus: “Decades-long group discussions, symposia and workshops were organized during those years, […] There are a number of other traveling circuses, and the names of the most important acrobats and other attractions are easily filled in: the now bankrupted traveling MBD Circus (Minimal Brain Damage), a traveling circus for The Whole Family, a traveling circus for Body Language (extended thanks to popular demand) and the traveling circus for Autism. Recently I was confronted with the traveling Incest circus.”

These limited exploratory frameworks follow one another in rapid succession (fear of failure, borderline, ADHD…) and have apparently only one thing in common beside their short-lived nature: the initial enthusiasm of their followers, which frequently appears in the form of a proselytizing zeal. Thus I was once asked by an alarmed doctor whether it was “really true that everything could be explained by and treated as hyperventilation?” Yet there is another, more important mutual factor: the cause or etiology is always situated in an accusatory way outside the subject, in some so-called third party. Either the parents didn’t do their job or the social machinery failed, launching one onto the somatic roller coaster. This is even more true of those I refer to as the guilt-tripping drama queens, as this is their leading trait.

The chief difference between the Latest One-Hit Wonders and the Guilt-Tripping Drama Queens is the much wider range of the latter, a quality that always appeals to the sense of guilt ever-present in everyone (“Use every man after his desert, and who shall ‘scape whipping?”—Shakespeare, Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2), cleverly channeling it into larger, nameless entities. The example that first comes to mind is youth addiction. Over three decades, we have had four different exploratory models, each creating its own individual furor at the time. In the ’60s, drug addiction was explained as an expression of youth protest against an authoritarian society. Yet, in the wake of the bankruptcy of May ’68, the same addiction was explained as the alleged general feeling of defeat and alienation among the youth of the very same society. From the ’70s on, in contrast, drug use was interpreted primarily as one of the effects of a society of excessive consumption, overloaded with well-being and opportunities. But this failed to account for similar drug problems in underprivileged and poor segments of society. The explanation was then sought in the weakening of family ties: the torrent of divorces and open marriages operated as a destabilizing factor for youth. At the same time, it was discovered that young people coming from stable economic and strict family structures had their own drug problems, collapsing this exploratory framework as well. In the ’80s the one-size-fits-all response was economic insecurity combined with unemployment, until the discovery that drug abuse was the order of the day in certain highly specialized, professional circles (Di Gennaro 1987). All this calls to mind the image of a weary social worker who, casting anxious eyes to heaven after his latest ongoing training session (“Remotivation of Unemployed Addicted Youth”), shuffles into the nearest bar and orders a double whiskey.

The next example belongs to the same, albeit larger field: youth deviance. Summing up the commonsensical attitude that has characterized the prevailing approach for a number of years, Walgrave (1979) observes,

Our society is heavily directed toward economic progress and hence, has become too competitive and too materialistic. A number of people cannot cope with the daily struggle any more […]. Therefore a group of people exists on the borders of normal society. […] These families live an irregular life, the kids are neglected. In such situations, it is normal for young people to be unable to adapt to society’s demands. They remain psychologically immature, have a lack of psychic inhibitions; they do poorly at school, remain unemployed. […] The prevailing image of youth care programs immediately follows on from these ideas. While society must defend itself against such behavior, the teenagers themselves ought not to be regarded as responsible for it. They are in fact the victims of the circumstances in which they are forced to live. [pp. 2–3]

Immediately after presenting this oh-so-understandable explanation, Walgrave proceeds to throw cold water on it. Within scarcely a page, this comprehensive construction falls to pieces. In accordance with the Porterfield study and ensuing research into the “dark number,” it is revealed that this framework does not so much present us with the etiology of deviant behavior, but rather with the jurisdictional criteria3 for selection, scarcely covering 15 percent of the estimated total…4

It should be evident that these are examples of a form of social critique. The accusatory and exculpatory aspects seem self-evident because it is a matter of youth, drugs, and deviant behavior. But these aspects, as we will see, go much further than that. The question of guilt lies at the heart of the more global paradigms as well.

A Word about Paradigms

The larger paradigms are found alongside and through these more limited and limiting conceptual frameworks. Their size does not prevent them from formally displaying the characteristics of a doxa, which can be briefly summed up as follows: blinding you to what lies outside the frame, they force you to see what lies within it—even with the trigger-effect: “Can’t you see it?”—while simultaneously reifying it.5 In the preliminary interviews, the therapist imagines herself to be discovering things, while in most cases she will do nothing but confirm—confirm what was presented in the training. Real discovery means one has to leave the well-trodden paths of the doxa and blaze one’s own trail. Hence the therapist and the patient both need the same thing: the ability to reflect that makes both distance and choice possible.

Today, we can identify three such paradigms, each one initially seeming quite different from the others: the medical-biological one, the psychological one, and the psychoanalytic one. The last is considered corny and outdated, while the medical paradigm has increasingly become the Real Thing, as the psychological paradigm is doing its utmost best to lose its soft image and look as hard as possible by importing elements from the medical corner. My argument is this: in spite of their differences, these three paradigms are identical to the extent that their application makes them function as a University discourse (as discussed below). This doesn’t necessarily have to be the case, but clinical practice testifies to it being less often the exception than the rule.

These paradigms can indeed be studied as realizations of the University discourse, the latter being a regression from the Master’s discourse. Here the power of discourse theory lies in its predictive value: whatever the differences between the paradigms in terms of content, on a formal level they will institute the very same social bond, including the identical relations of impotence and impossibility. This is the most important thing: beyond the ever-present seduction of different concepts, theories, and explanations, we must concentrate our full attention on the almost incidentally created social relations.

THE MEDICAL-BIOLOGICAL PARADIGM, OR THE WET DREAM OF HARD SCIENCE

Because this approach sounds simple, it is therefore easy to sell: the cause of all human affliction is located in one way or another in the body. Therefore, diagnosis and treatment ultimately have to be grounded there as well, at least once science knows everything that there is to know. The old fashioned anatomical (or anato)-pathological model has today been replaced by a neurobiological-genetic one, but this is nothing but a turning of the tables. History, however, has shown that things are a little more complex.

From Dualism…

The starting point of what we call “reductive materialism” can be found in the fifth century B.C., with Democritus. Its basic argument is that both the ontological and the actual can be reduced to their fundamental composite particles. With Descartes and Newton, the emphasis is on mechanics, whose laws would explain “everything.” In Descartes’ Discourse on Method, the laws of mechanics are the same as the ones governing nature. With Newton, this becomes “the billiard ball universe.” Its explicit application to mankind is found in De La Mettrie’s Man as a Machine (1758), with Changeux’s Neuronal Man (1983) as a modern variation.

Meanwhile, Plato inaugurated a division between soul and body one that became hierarchized in medieval times: the soul is the highest good, the flesh is weak and perishable, subordinated to the eternal soul. With Descartes, this philosophical background will cause a division in thought and hence in education: the body belongs to the medical department, the soul is reserved for the shepherds of the soul—or the psyche as psychologists call it. Since the Enlightenment, the shift in emphasis from the religious-spiritual to the profane-material has brought the vilified body back into the center of the scientific enterprise, always within this materialistic-mechanical way of thinking, and along with the already mentioned division between body and soul.

Applied to our subject, psychopathology and psychodiagnostics, the same dualistic ideas quickly reappear.6 At this point, we can turn to Condillac and eighteenth-century materialism, of which positivism is a later offshoot. Prototypical for Condillac is his concept of “the statue.” He begins with a fictional human statue that initially has only one sense-organ, resulting in a single perception. After the statue acquires a second sense-organ, and hence a second perception, other functions get installed: a memory of the first perception; a comparison between the first and the second; a judgment containing a reflection and, finally, a desiring imagination that is able to present the no longer visible object. These are the so-called human faculties, which, for Condillac, always come down to transformed perceptions focused on the body as a material medium. We will encounter these faculties again in the psychology of the functions, dressed this time in somewhat more contemporary garb.

The scientific method that is based on these premises can be described as follows: science is a mental activity that always begins with the observation of phenomena, that is, sensation, whose aim is the application of a systematic ordering of that observation through the comparison, differentiation, and classification of the elements according to their resemblances and differences. In other words, decomposition and recomposition based on observation. The entirety is orchestrated by language, hence Condillac’s famous remark that a perfect science would be a perfect language. With regard to psychodiagnostics, this would lead us to the ideal of a perfectly closed nosological system of categorizations and denominations.

It must be emphasized that this approach was primarily dualistic, meaning that the psyche and the soma occupied equal places. For instance, half a century later, we will encounter this again in Leuret, who in his Fragments psychologiques sur la folie (1834) places hallucination into two categories:

-

Psychic hallucinations, missing the sensory element, but with a xenopathic or “alien-subject” character. Its normal variations can be found in “inspiration,” which seems to come from outside the subject and does not necessarily have to be sensory or sensual, as with the Muses, for example.

-

Psycho-sensory hallucinations resembling the first, but with a sensory quality. This quality is explained by referring to a perceptual-neurological factor that is thought to play a role here.

The two types sit beside one another in the dualistic line of reasoning of Pinel and Esquirol, where certain psychopathological deviations are the consequence of clearly visible, somatic disorders, such as idiocy. In contrast, madness in its pure form, has no lesional basis and can be described as an unknown functional change in the psychic apparatus.

…to the Opposition between Anatomists and Functionalists…

This dualism was gradually left behind, firstly with Gall’s phrenology at the end of the eighteenth century. As a neuroanatomist, Gall discovered the difference between the grey and white matter in the brain. From this, he developed a speculative theory about where the mental faculties in the cortex were located, convinced as he was of a quantitatively proportional correlation: the larger a certain region in the brain, the more important the faculty that it contained. This is the theory of the so-called cranial knobs, which postulates that each psychic function belongs to a part of the brain that can be topographically identified and isolated. In this manner, Gall and his pupils isolated some thirty-five faculties in as many corresponding knobs, including ones for poetry, for mathematics, and even one for conflict.

The immense success of this theory is still evident in certain colloquial expressions in German and Dutch where to “have a knob” for something means to have a particular talent for it. Nevertheless, this success was unable to prevent Gall’s phrenology from being officially condemned by the Austrian government in 1802 (because of its allegedly antireligious content), forcing him to leave the country. One of the reasons for its success was that it seemed as if he had found a material substrate for monomania, a nosological category of Esquirol’s that was causing a great furor at that time. As partial afflictions involving a single faculty, the various monomanias were thought to correspond with the yet-to-be discovered responsible knobs. In complementing each other perfectly, the success of these theories was more or less inevitable.

From Gall onward, two different approaches to psychopathology went into action: it was the anatomists versus the functionalists. The anatomists toed the phrenological line, advocating a certain monism: every mental alienation presupposes a specific cause in the brain that must be hunted down. Pinel’s moral etiology and treatment was tossed out as old-fashioned. More skeptical, and remaining within the dualistic reasoning of a Pinel and Esquirol, were the functionalists. For them, cerebral lesions are in most cases either undetectable or their relationship to psychopathology cannot be demonstrated. They do not deny that the body plays a role, but refuse to recognize it as the exclusive causal factor. For the functionalists, the cause of psychopathology lies outside the body but has effects on this body’s functions. Hence their name: functionalism, functional disturbances.

After Gall, the opposition between the anatomists and the functionalists gets consolidated by Georget. He will introduce a division that will continue to govern the clinic until today. In On Madness (1820), he distinguishes between:

-

Mental deviations that are merely symptoms of a known organic disorder. The causal factor lies in the body. From a nosological perspective, he locates the “acute delusions” here, which are nothing but a symptom of an already discovered organic disorder. In this category, for instance, we find delirium caused by fever, brain damage, and the intoxication psychoses.

-

“Madness” proper, as an idiopathic affliction whose cause is unknown, and which is expressed by purely functional disturbances. While the symptoms are of a psychological nature, this does not mean that they have no impact on the body. The cause must be sought in the moral realm.

Furthermore—and this is what is new—Georget introduces the idea of evolution within these afflictions, an idea that forms the basis for what will later be called the “dynamic” point of view.7

This division is the precursor to the subsequent partition of neurology and psychiatry, recently given new form in the split between neuro-psychology and clinical psychology. Here, too, we find another of today’s oppositions: the first group focuses primarily on the illness, the second on the patient.

As a result, the two conceptions that originally sat alongside one other, or even merged with one another, are now replaced by an opposition between the anatomists and the functionalists. But the scales will soon tip heavily toward the anatomical side because of a certain discovery. From that moment onward, anato-pathology becomes the new Enlightenment in nosological thought. I refer here to Bayle’s discovery of paralytic dementia.

…to the Anato-pathological Paradigm

Appearing in 1822, Bayle’s discovery emerges almost simultaneously with Georget’s theory. Nevertheless, its effect will only appear some twenty years later and, under Kraepelin’s influence, will color contemporary nosological and diagnostic thought in a lasting way.

The effect of this discovery has to be seen against its historical background. The phenomenon of general paralysis (paralysie générale) was known long before Bayle, and was considered to be a symptom or complication of the terminal stages of several diseases. It is precisely this thesis that he will reverse: general paralysis is caused by a single organic factor; it is a single disease that evolves through different stages. At a stroke, nosology seemed a whole lot simpler. At least three different illnesses could be reduced to a larger whole, of which each is an evolutionary stage; the previously random symptom of general paralysis is now unified into a single syndrome whose organic causality has been proved. Bayle’s discoveries can be briefly summarized as follows:

-

General paralysis is caused by a chronic inflammation of the brain (meningitis of the arachnoid membrane).

-

This inflammation leads to a psychopathology that normally undergoes three stages, spread over several years:

-

delusion with exaltation (or occasionally depression);

-

delusion with mania, megalomania, furor, agitation, logorrhea;

-

delusion with deterioration, amnesia and dementia.

-

We will come back to the question of the value of this description. Bayle propagates his discovery as the prototype for the entire field of psychopathology: every psychopathological disturbance is merely a symptom of an underlying anato-pathological process. From 1850 on, this idea becomes ubiquitous. Research into psychosis, chronic alcoholism, epilepsy, and even hysteria becomes the search for their underlying somatic bases. “General paralysis,” better known to us as “paralytic dementia,” becomes the Medusa-head around which a whole generation of researchers became paralyzed, with Kraepelin as her principal victim. With this discovery, the balance is also tipped and etiological research becomes exclusively directed at the body: every psychopathology has an organic base and is therefore organically treatable. Anato-pathology is a fact. Virchow’s Cellularpathology (1858) becomes the leading paradigm that extends into the entire field of medicine, culminating in enormous progress in this field.

As for the value of this discovery for psychopathology, we have to consider it carefully—one must first distinguish between the value of the discovery itself and the idealizing generalization that followed afterward. Bayle’s discovery became the subject of subsequent research, enabling Fournier in 1879 to demonstrate a connection with a syphilitic etiology, while in 1905 Schaudinn discovered Treponema pallidum in the infected sexual organs.8 In 1913, Noguchi demonstrated the presence of Treponema in the brains of paralytic dementia patients. These therapeutic attempts were topped off with Mahoney’s 1943 discovery that penicillin could be used, making paralytic dementia today a rare phenomenon. Such, at least, were the discoveries, still revolutionary today.

But once we examine the accompanying idealizations, the Medusa-head aspect becomes more equivocal. Paralytic dementia becomes the paradigm par excellence of the syndrome, as developed later by Kraepelin; according to Kraepelin, psychopathology ought to distinguish among syndromes that possess the same cause, exhibit the same somatic and psychological clinical picture, and follow the same evolution.

Unfortunately, even in the case of paralytic dementia, this idea of a uniform syndrome is more dream than reality, something that is usually forgotten thanks to the subsequent idealizations. Despite its clear organicism, the unequivocal factor is missing, meaning that the diagnosis isn’t unequivocal either. Only a limited number of syphilitic patients develop paralytic dementia, for example, forcing one to rethink its organic causality. The long cherished idea that there could be two viruses at play, only one of which caused paralytic dementia, was never proved and finally had to be given up (see Ey and colleagues 1974, pp. 835–836). The clinical evolutionary picture for psychopathology, for instance, can take many different forms; every textbook presents different classifications, most of which, moreover, contain “rare” or “atypical” forms. For example, the most frequent form before the turn of the century, megalomania, appears to have been replaced after the First World War by a simple form of dementia, a shift that a famous clinician like Rümke recognizes as being the effect of the dominant discourse, and which certainly doesn’t tally with the idea of an unequivocal somatic cause (Rümke 1971, p. 78).

These difficulties argue against an exclusively organic approach. We may conclude with Bayle then, that the somatic part of a certain disorder was indeed discovered, but that the mind–body division and—in the case of general paralysis—the exclusion of the psyche, inevitably lead to the classic deadlocks of the artificial dichotomy psyche–soma; all we can do is make an entreaty to try to think beyond this dichotomy.9 The unequivocal and one-to-one correspondence between somatic etiology and psychopathology that Kraepelin so desired is an illusion, leading Nijs, in 1987, to invert Kraepelin’s statement in the following way: “Organically caused psychiatric disturbances are typical to the extent that they are atypical.”

The Paradigm: Kraepelin and the Uniform Syndrome

Despite the difficulties of applying the idea of the “uniform syndrome,” paralytic dementia became the leading paradigm. The idea of the uniform syndrome is nothing but another name for the Platonic invariant. As a result, in the second half of the nineteenth century, research concentrated on the search for the anatomical substrates of every psychopathology, and for epilepsy, chronic alcoholism, and hysteria in particular. Autopsy became the primary research method, through which one hoped to find “it,” despite not really knowing what “it” was.

Nevertheless, the results failed to materialize. Consequently, that conviction weakened and, instead, the idea of degeneration took center stage as a reversed illustration of Darwin’s theory of evolution. With Freud, however, a new path was blazed: psychopathology concerns not simply the body but also and even primarily the psyche. The failure of anato-pathology in hysteria—see Charcot—inaugurated psychotherapy and psychodiagnostics. From this period onward, the anato-pathological conviction wanes and there is renewed attention to more wideranging approaches that take the interaction between the individual and his surroundings as a central theme.

This does not exclude the idea of an organic determination continuing to play in the background. The power of this ideal increased once clinical experience with paralytic dementia disappeared. Indeed, thanks to successful treatment, it has become quite rare, meaning that many clinicians in training do not experience the restrictions of the purely organic causal factor described above. The Kraepelinian ideal will receive fresh blood from the 1950s onward, due to the purely accidental pharmacological discovery of the precursors of neuroleptics. If chemical substances can exercise a more or less normalizing influence on psychotic behavior, then its cause and etiology must be on the biochemical level as well (Bouhuys and Van Den Hoofdakker 1986).

Meanwhile, this anato-pathological model has more or less become history, having been replaced by a new show pony, namely genetics and, more specifically for our field, behavioral genetics. Dressed up in a different outfit, it is the very same belief. A torrent of quantitative research has been published in the past decade, all demonstrating that certain behavioral characteristics are significantly determined by genetics, with only a limited environmental influence (for a review and a critique, see Fonagy et al. 2002, pp. 97–145). Nevertheless, it is enough just to examine recent changes in elementary bodily characteristics (such as bodily length, onset of menses) to see that the environment has a massive and, above all, barely understood influence on features that are undeniably genetically determined. It becomes all the more complex once we study non-elementary characteristics such as schizophrenia and delinquent behavior.10 Nevertheless, this conviction is rapidly gaining ever more ground as the new doxa. Rather than “anatomy is destiny,” the bell now tolls: “genes are destiny.” The difficulty of thinking about the interaction between nature and nurture is avoided. Behavioral genetics are the Latest One-Act Wonder.

The Hidden Moral in the Story: The University Discourse

So far we have recounted the history of this paradigm, emphasizing its factual content. But beyond this, we need to call attention to another aspect, namely, its formal mode of operation. My argument is that such a paradigm operates chiefly according to the University discourse, through which certain relationships and positions are imperceptibly imposed on the participants. Furthermore, this occurs independently of both the content and the scientific quality of the paradigm.

The reason why we encounter the University discourse here has to do with the radical impossibility of maintaining the Master’s discourse (Lacan 1991 [1969–1970]). The University discourse is easier and, moreover, fits in with today’s scientistic climate. The positions and disjunctions remain the same, but the terms have undergone a quarter-turn shift from those of the master discourse.

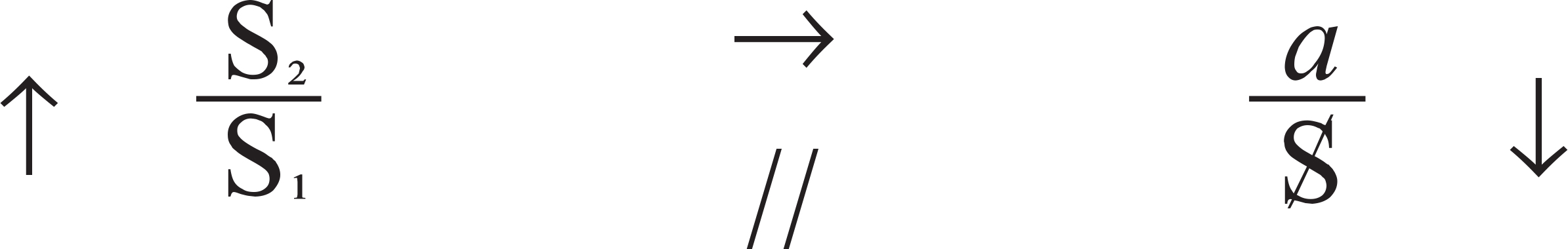

To put it schematically: this time the agent is the knowledge base from which the diagnostician and therapist approach the other as an object to whom this knowledge can be applied. Behind the agent lies the unquestioned and unquestionable master signifier. The product of this approach is that the other, placed in the position of an object, becomes more of a divided subject than ever. The relation between this subject and the master theory comes down to an unbridgeable gap, meaning that the upper relationship becomes impossible as well. The whole is moreover supported by a certain conception of science that ultimately excludes the subject as such. In spite of its apparent objectivity, this approach is fundamentally morally-ethically colored through and through. Let us look at it more closely.

Compelling Explanations

Knowledge, S2, occupies the place of the agent. This knowledge is not merely knowledge per se, but first and foremost a certain conviction: it has to be so, reality has to correspond to this knowledge. To the extent that reality doesn’t yet correspond to it, it is only a matter of time. The basis of this conviction is found in a now incontrovertible master signifier S1, which serves as a shining example. We already found one such compelling expectation—a doxa—back in 1917 with the reference to Kraepelin and paralytic dementia:

The nature of most mental disorders is still unknown. But there can be no doubt that future research shall enlighten the question and uncover new facts in a science which is for the moment only in its infancy. In this domain, the disorders caused by syphilis provide us with a vast field of investigation. It is logical to assume that we will succeed in discovering the causes of other forms of madness, and hence to prevent them, maybe cure them, although for the moment we don’t have any indication whatsoever. [Quoted in Szasz 1983, p. 45]

In response to this, we can cite another celebrity: “In an attempt to go further into the psychological, people cling to newly discovered somatic phenomena, or pin all hope on experiments through which something measurable, visible, a curve that can be mapped onto a graph, must finally come to light.”11

The scientific outlook is the positivist, even scientistic paradigm.12 Its specific conviction with respect to our field can be put this way: every psychological disorder has, that is to say, must have an organic cause. While this cause has already been found for a number of disorders, the others need further, intensive research, which will eventually lead to their discovery as well. In the meantime, for lack of anything better, we must content ourselves with psychotherapy, but the day will soon come when a pill, or a surgical intervention will suffice. The implication of such a scientific approach is immediately clear: if schizophrenia, for instance, is caused by a disturbance in neurotransmitters, then psychotherapy doesn’t make much sense. Rather, one must consider pharmacological, even neurosurgical interventions, if necessary. From this perspective, research into the schizophrenogenic family is an outdated anachronism that ought not to be funded.

We have already seen how the unprovability of this paradigm can be conceived in terms of an epistemological impossibility; this means that what we are dealing with here is a doxa. Its success, despite its lack of scientific persuasiveness, has to do with its hidden moral component, which we shall come to shortly. Put in terms of discourse theory, what we see here is the relation between knowledge (S2), as the apparent agent, and a belief in the master signifier (S1) occupying the position of truth and in fact governing the whole thing.

Illness as an Essence

If we pursue the structure of the University discourse further, we find that the other is reduced to an object, producing a heightened awareness of division and subjectivity on the patient’s side. Illness is defined as a nosological essence, for which the patient supplies only the fertile soil, a temporary dwelling. To put it more strongly, as a substrate, the patient muddies the disease’s pure expression, just as soil that is too barren or too rich has effects on the form of the plant that happens to grow on it. “Anyone who describes an illness, has to make a careful differentiation between the symptoms that necessarily go with it and are specific to it, and the symptoms that are only accidental and coincidental, such as the symptoms depending on the temperament and the age of the patient,” writes Sydenhan in 1772 (cited in Foucault 1997, p. 27).

The very same subdivision between the essential, which belongs to the illness’s essence, and the secondary, which is caused by the specificity of the patient, can be found throughout the history of nosology, in Charcot (real hysteria versus “formes frustes,” or weaker versions), just as in Bleuler and Schneider (primary versus secondary symptoms), to name only the principal figures. The emphasis of medical science is not on the patient but on the illness, an idea we have already seen in the DSM with its stress on the various “disorders.” The patient must be abstracted away if a clear picture is to emerge: “The Creator has established the course of most diseases by means of invariable laws that can be discovered quickly enough, if the patient does not interrupt or disturb the course of the illness.”13 When the body is considered a mere substrate, the subject is at most the passive victim of an organic agent. The etiological agent lies, like a “foreign body,” a Fremdkörper, outside the subject itself, who has little to do with it aside from being “overtaken” by it.

To put this in terms of discourse theory, in the University discourse, one finds an object rather than a subject in the place of the other. Objectification and desubjectivation are well-known in medical practice. This is, in fact, the classic critique of the medical model: being reduced to a “case” (the ulcer in room 2B) generates indignation in the patient—that is, a demand for recognition as an individual human being. But there is one tiny detail: in this discourse the subject is, quite precisely, produced by this approach; without it, there would not have been any subject whatsoever. With this approach, it appears in the position of the product. Such a protest, incidentally, conceals an underlying benefit for the subject itself, and therefore needs to be taken, at least partially, with a grain of salt. This becomes clearer once we take the ethical-moral aspect into account. The argument is quite simple: if a certain psychopathology has an organic explanation, then there is no such thing as a guilty party. There are only victims of accidental gene combinations, of external, nonhuman toxins, and so on. The parties themselves are not to blame, that’s the ultimate message.14 However, should the same disorder have a psychological etiology, then we would have to look for a cause in the psyche itself, and hence for a causal agent, either in the environment or, more frighteningly, in the mirror. This opens up a quasi-juridical process in which it is not just the patient, but the parents and the partner as well, who must all take their places in front of a prosecuting jury of psy’s (Fischer and van Vliet 1986, pp. 137–139, 148).

This is the advantage of the anato-pathological paradigm for the patient: he or she is acquitted and, moreover, can protest that his or her subjectivity wasn’t taken into account. The consequences of such an approach go much further than one would imagine. In fact, they color the entire mentality of our health-care system,15 which can be summed up in the following slogan: “Health is everyone’s free right.” The result, predictably enough, is that everyone avoids their own responsibility and choices. Lung cancer? No problem, just sue the tobacco industry, it’s all their fault! Alcoholism? That is simply an illness that one “has” (I have the flu; I suffer from alcoholism), what an awful tragedy!

Put in terms of discourse theory, what we encounter here are the disjunctions, which go considerably further than the purely anato-pathological or medical aspect of this approach. On the upper level, it becomes apparent that knowledge is never fully able to grasp the object; there is always a gap and a remainder. On the lower level, it is clear that the subject, in the position of the product, neither has nor wants anything to do with the master signifier S1 in the position of cause and of truth. The double bar // will never be overcome.

We are now in a position to examine the other paradigm in which the moral element is explicitly foregrounded.

THE MORAL TREATMENT PARADIGM: TO TEACH SOMEBODY MORES

We could, fairly arbitrarily, begin with Pinel (1754–1826), one of the founding fathers of what would later become psychiatry and psychopathology. Like every founding father, he is described in mythical terms: heir to the French Revolution, severer of the chains that fettered the mentally ill, and so on. His essential significance lies neither in the field of nosology nor in that of theory. Pinel is important because of his method: he was the founder of the clinic, that is to say, of the determined and systematic approach through which mental illness acquired its distinctive status, institutions, and treatment.

With regard to theory, he took a rather peculiar stance: he remained skeptical of any form of theory that, as far as he was concerned, moved too rapidly away from observation. Hence one cannot talk about Pinelian theory. Rather, he proposed a pragmatic approach, a form of know-how (savoir-faire) that enters history under the name of the “moral treatment” (traitement moral). This approach accords with his views on etiology. He distinguishes between three groups of pathogenic factors:

-

Physical causes (trauma, organic diseases);

-

Hereditary causes (debility);

-

Moral causes.

Deeming the first two practically incurable, he concentrates on the third group. His ensuing treatment model recalls the Hippocratic idea of illness, in which illness is the body’s healthy defensive reaction to an imbalance, and whose normal result is health. It is clear that such a conception of illness has important repercussions for the way the person who was then called the “alienist” responds. Pinel sums this up in three basic rules:

-

He has to wait;

-

He has to avoid any intervention that disturbs the natural course of the illness (because its ultimate goal is health);

-

He must help the illness progress.

It is precisely this last that constitutes the “moral treatment.”

The underlying theory originates in sensationalism: the contents of the sick mind stem largely from deleterious perceptions and sensations, that is, Pinel’s third etiological factor. Consequently, curing boils down to the presentation of health-inducing perceptions and sensations, combined with the patient’s removal from the harmful environment so that his or her psychic “faculties” can recover their balance. The practical effects of this project meant that special institutions had to be created for the recovery process—psychiatric hospitals—where the healthy perceptions could be effective. This gave rise to the application of a variety of cures (mud, water, sun and other baths) intended to create healing perceptions. Each one of these cures forms only part of a total approach because these institutions will eventually give birth to the clinic, the characteristic, all-encompassing regime that is to effect moral healing in the form of a kind of strict paternal order that is incarnated by the clinical director himself.

With this we have already sketched a brief outline of the core of the moral treatment model: people become mentally ill because of deleterious perceptions, ideas, norms; psychotherapy occurs by grace of a master figure whose correcting interventions take place within the context of a larger environment, or—more precisely—inside a totalitarian discourse that has no room for the subject’s division. Note here that morals are considered health inducing. After Freud, this gets reversed, and morals seem to become the most significant deleterious factor (Vandermeersch 1978, p. 45). Later on, this core will be mitigated somewhat, but in essence it remains unchanged. For instance, for Pinel, the mental faculties were autonomous and nonhierarchized. Psychic functioning was a process of interaction in which upsets of balance could take place, resulting in psychopathology. From Esquirol (1772–1840) onward, a hierarchical order gets introduced: at the top of the faculties lies a function that controls, selects, and synthesizes, namely, the ego as the center of attention. Consequently, psychological disturbances are conceived as an effect of an imbalance between the lower faculties and the higher attention function of the ego.

This shift is significant because it continues to determine contemporary thinking; even today, psychology is frequently simply an “egology,” with the emphasis today on what are termed cognitions. While in Pinel’s time people were permitted to be both passionate and rational, now rationality dominates. Throughout history, the pendulum has swung back and forth: in pragmatic eras, man is thought to be rational (cool), while in more expressive periods passion is allowed. Anyone unlucky enough to respond to period X with image Y deviates from the ideal norm.

Guislain and Phrénopathie

Somewhat closer to us in time is Guislain (1797–1860). He replaced what was then termed madness (folie) with phrénopathie, understood as “a psychological reaction to a state of phrenalgia.” We can extract two things from this description: a psychological reaction and phrenalgia. Guislain looks for the model of the psychological reaction in normality. For him, there are always both normal and pathological variations, and he remarks dryly that the success of the treatment depends on the degree of distance between the pathological and the normal. He conceives of “phrenalgia” as a moral affliction (une douleur morale), and it is precisely this aspect that will subsequently become a bone of contention. As a general practitioner in Ghent, he was able to keep abreast of the same families for many decades, which taught him, firstly, that the cause of psychopathology was always to be found in what he called the moral sphere and, secondly, that this cause was almost invariably kept from outsiders. As a result, his position was that “one must look behind the scenes.” This idea finally became commonly accepted, and influenced, for example, Griesinger’s theory of conflict, and consequently Freud as well (see, for example, his notions of conflict and defense).

With regard to specifically nosological classifications, Guislain remains adamant that the pure forms are very rare and that one mostly encounters hybrid forms in the clinic. This is unquestionably true. What is weird is how the vast majority of us continue to think and rationalize in terms of strictly separated species, turning clinical experience into a kind of aberration of the pure, rational, nosological system.

The beauty of it—which is precisely why Guislain was picked here—is the superb confusion that appears in his terminology, which is by no means accidental: in it, “moral” states are rechristened as medical-organic afflictions (phrenalgia, phrenopathie), blurring the differences in content between the two paradigms.

Protagoras to Pinel

We took Pinel as an arbitrary starting point. We could just as easily add a number of other writers from around the same time to the discussion, but this won’t be necessary for our purposes. The moral conception of illness actually goes directly back to Protagoras and from the beginning exhibits the very same paradox. This sophist from the fifth century B.C. became well known for his argument that “man is the measure of all things” (homo mensura), thus reducing all perceptions to the subjectivity of the perceiving subject, and hence to a merely individual truth. What person X perceives is not necessarily the same as person Y; but the two different perceptions of the same reality are nevertheless each “true,” albeit only for a single person. Even Protagoras, however, allowed that certain perceptions are better than others, namely, those belonging to healthy rather than sick persons. He conceives of a pedagogical role for the therapist, who must teach the patient-pupil the proper perceptions. What is better is what has better actual effects. As a result, we are faced with a paradox: the actual is only subjectively perceptible, while different “better actual effects” result from different perceptions. The master position becomes inevitable here, and that is precisely what we find with Pinel’s chef de clinique. Historically speaking, it is here that the enlightened appeal to reason always shows up as the decisive argument, from Kant (“The only feature common to all mental disorders is the loss of common sense (sensus communis) and the compensatory development of a unique, private sense (sensus privatus) of reasoning”) to Monod.16

In this way a line can be drawn from the Greek sophists to Pinel. We can pass over this quietly—it is old-fashioned, goes back to prescientific times, and the like. However, when we make the step to contemporary psychological approaches we are in for a double surprise.

Firstly, we find almost exactly the same problems in today’s psyclinical practice. You don’t need much clinical experience to discover that most psychological problems are concerned with psychosexual identity (“What does it mean to be a man? What does it mean to be a woman?”), with the psychosexual relationship (“Where do I stand in relation to the other, my partner?”) and with the relationship toward authority (classically the father, nowadays less clear). It is also well known that these problems always imply a conflict between pleasure and unpleasure in every conceivable form (from anxiety to jouissance). The contemporary clinic, in other words, is still very much a moral clinic, although the signifier “moral” has been unilaterally replaced by the “psychological.”17 The reason for this substitution is not only historical, but also epistemological. The term “moral” doesn’t fit very well into a positive-scientific way of thinking, and “ethical” only barely, but “psychological” does the job nicely.

The second surprise concerns the difference between the contemporary clinic and the medical-biological approach described above, which one would expect to be substantial. Isn’t the subject, after all, the main focus of clinical psychology, not the body? Closer examination, however, reveals a surprising result. The difference between clinical psychological and medical biological approaches is minor, provided that in both situations they take place within the University discourse. The most important difference seems to come down to the fact that, compared with the organic-medical approach, today’s “moral treatment” is unable to convincingly refer to a master signifier in the same way, so that it is more a question of aspiring toward a guaranteeing master signifier S1. This is, incidentally, more or less the sole difference, for we encounter the same ideas again, with the very same deadlocks. Consequently, the implications of today’s moral treatment, that is, psychotherapy within the terms of the University discourse, are identical to those of the organic-medical treatment, with the exception of the aforementioned aspiration. We have already mapped them out through the University discourse, and can take them up again here virtually unchanged. To avoid repeating myself, I shall pay special attention to the subject, because one would expect it to have a central place within this approach.

The Exoneration and Infantilization of the Subject

The upper level of the University discourse shows how an object appears in the position of the other to which knowledge is then applied. In the organic-medical approach, the subject is regarded as a victim of external biological agents. In what we might call the hidden moral paradigm, the subject is a victim of its environment (parents, family, job), which must be objectively studied and mapped out—the enmeshed family, the disengaged family, the schizophrenic mother, the hysterogenic father. This means that the medical-biological line of reasoning can also be applied, but with psychological concepts for content. The psychological becomes pseudo-medical. This equivalence doesn’t mean that psychology acquires medical contents (in the sense of MBD, ADHD,18 or lack of oxygen at birth, for example), but points to a formal similarity: the etiological agent is located outside the subject, who remains more or less unimplicated in it but is, rather, assailed by it. The medical and the psychological are both alienating discourses precisely because of this exclusion of the subject.

Hence, in the University discourse (whether clinical-psychological or anato-pathological), we encounter a diagnostic logic that excludes the subject: the subject is merely a product that an agent, such as a foreign body, psychic virus, or bacteria, has acted on. Such an etiology can seem quite psychological. Every time anxiety, for example, is explained and diagnosed through reference to a birth trauma, or hysteria by a traumatic experience before the patient was four, or learning difficulties by the parents’ divorce, it sounds quite psychological.19 Nevertheless, this logic is fundamentally alien to the subject, referring to something that comes from the outside and that can be objectively retraced.

The metaphor that we used with the organic biological paradigm, where illness was a plant and the subject its soil, applies here as well. This time the poorly developed plant represents the subject that has languished because of a bad soil. Both diagnosis and treatment start with the definition of an ideal plant and an ideal terrain. The subject—the plant—comes into the picture only as a goal, a final product of the process that is primarily concentrated on the improvement of the potting mix. Diagnosis here does not so much measure the subject’s difficulties as the distance between the subject and the presented ideal. We obtain, as it were, a picture of a gradually elaborated path that starts out far from the norm and ends up in perfect accord with it. The subject will be situated in its corresponding place on this continuum through which one can then estimate the distance he or she still has to cover.20

What is striking in this approach is how difficult it is to found the treatment: what is one to do with the irrevocable “facts”? An external etiology implies an external treatment. In bronchitis, the subject becomes the victim of an attack by a bunch of little critters; one is given antibiotics to kill the bacteria. But what should one do if the subject is the victim of a birth trauma, the parents’ divorce, or…? In such cases, the only real antibiotic, in the etymological sense of the word (translator’s note: Anti-biotics: literally anti-life), would seem to be that most radical one, evoking the mè funai of the chorus in Oedipus Rex: “It would have been better never to have been born.” In this context, one reaches for a double arsenal, with reparative techniques (the original learning process must be redone) and various abreaction predicaments (re-birthing, primal scream) on the one hand, and recovery techniques for changing the originally faulty substrate into an ideal form on the other. In both cases, therapy runs the risk of deteriorating into a patronizing helping hand. The subject, in all of this, is exonerated of guilt; it is purely the environment that is to blame. The price is infantilization. As a flawed product, the subject is nothing but the raw material upon which other, better designers will do their job; nothing but the starting point for a new improved edition.

Enforcing the Ideal

This turns the vast majority of contemporary therapeutic approaches into covertly moral projects, not so much because they conduct everything under the banner of the ideal (in whatever version) but because they coercively enforce it. Hence, psychopathology is considered a failure to correspond with a certain ideal and treatment boils down to an educative process, a kind of relearning of this ideal. The moral dimension is expressly present, although now disguised under a pseudoscientific veil: psychological health becomes a coercive yoke, an obligatory conformity to a prescribed norm as the incarnation of the health ideal. The difference between psychotherapy, education, and re-education becomes completely blurred.21

No wonder that educational psychology, cognitive psychology, and psychotherapy have become confused today, and that one frequently talks about psychological training, preferably in groups where the effects of transference and identification are much greater. When Foudraine wanted to demedicalize his ward in Chestnut Lodge, the most fitting new name he found for it was “School for Living.”22 What makes this still weirder is that, after Freud, we do have some concept of the subjective implication: ideas such as the “benefit of illness” and “choice of neurosis” can serve us as beacons for avoiding this subject-infantilizing approach. We might add that Freud himself originally used these ideas of external factors, because that was how his hysterical patients presented it: something attacked them from outside—see his first theory of trauma. But long before he officially gave up on this theory, he wrote that the so-called “foreign bodies” formed part of the subject’s ego, meaning that from the early Freud onward we must look for the etiology in the subject itself (Freud and Breuer 1978 [1895d], pp. 6–16).

The results of such an external approach can easily be foreseen: maintaining this objectifying and patriarchal mode will lead patients to denounce the entire psy-enterprise, just as they did with the older medical model.23 Nevertheless, complaining about it doesn’t prevent them also from benefiting from it, through the patient’s self-exoneration, which is why the system endures. But it also creates fertile ground for all kinds of alternative healers, some of whom may be more willing to listen than regular therapists.

Rejecting the Subject

The idea that, as a result of the moral approach, the subject itself can be blamed and therefore rejected is at first sight perhaps even more surprising than simply the chill exclusion of the subject. Unexpectedly enough, we find an illustration of this in Thomas Szasz. This well-known freedom fighter from the anti-psychiatry movement has always presented himself as a defender of the rights of the mentally ill; he was a relentless critic of everything and everyone who threatened these rights. It is less well known that he ultimately rejected the patient, and that this is a necessary consequence of his approach.

His basic thesis is as simple as it is seductive: psychopathology is an effect of oppression, comparable to the medieval Inquisition. Moreover, he makes a black-and-white distinction between illness on the one hand and psychic difficulties on the other. Illness is biological and belongs to the field of the positive medical sciences, the world of laboratories and scanners. Natural science for him is the only genuine form of science. In contrast, psychiatry and psychology, to which psychic troubles belong as general problems in human life, inevitably have to enter the fields of morals and ethics, and therefore are unscientific by definition (Pols 1984, p. 58 and passim). As a result, he argues against enforced institutional psychiatry and in favor of what is known as “contractual” treatment, whereby patients come for consultation of their own free will with the aim of regaining their lost freedom or autonomy.

These arguments seem beautiful, human, modern, and so on. Nevertheless, they become somewhat less attractive once we follow his reasoning through to its final consequences, which inevitably lead to a deadlock and a paradox.

Let us deal with the deadlock first. Everything to do with institutional psychiatry Szasz interprets in terms of the relationship between oppressor and oppressed. In itself this is not new. As an idea it can be put into the context of much wider theories than anti-psychiatry, where mental illness is reduced to a question of power and oppression. Let us sum them up. In philosophy, we encounter this idea in Hegel, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche. In our own field, it already takes center stage from the moral treatment model onward. In Freud, the important but often neglected opposition between passive and active is apparent throughout his work. In Adler, we find the theory of masculine protest and organ inferiority. Behavioral therapy is an open-and-shut case of power at work, while in systemic therapy the ideas of one-up and one-down speak for themselves. In ego analysis, the concepts of resistance and adaptation are fundamental. Lesser gods are Bakker with his theory on the territorium and Laborit with his similarly ethologically inspired ideas of hierarchy and dominance. With Foucault, we find an explicit relation between discourse and power. Finally, Lacan equates the discourse of the unconscious with the discourse of the Master and considers the latter the necessary precondition for every possible discourse and hence for every possible social relationship. Consequently, he does not naively reject this master discourse but links it structurally to the three other discourses.

In other words, if Szasz centralizes the idea of power and oppression, he inserts himself into a long tradition. But with this he makes a substantial error of interpretation: the relationship between oppressor and oppressed is primarily internal to the subject that is divided between its desire and its truth, and this relationship only becomes externalized afterward, resulting in the creation of oppressive instances, institutions, and so forth. For both Lacan and Freud, family and society are the effects of a certain subject-formation, not causes, albeit in a perpetually circular relationship (Freud 1978 [1930]; Lacan 1990 [1974], pp. 28, 30).

Szasz concentrates on these effects and calls them causes. His error becomes visible in the deadlock we can observe in his treatment: when one removes all external oppressive factors, the individual psychopathology remains. Precisely at that moment, Szasz’s attitude shifts into the rejection mentioned above: the patients cannot cope with their liberty, with their autonomy.

This brings us to the paradox. Despite all of his pleas for freedom and autonomy, his theory finally amounts to a direct rejection of the patient. Why? Because his (in many respects justified) critique of institutional psychiatry, and his black-and-white distinction between science and ethics lead him back to the moral treatment model of the alienist, upon which his thought acquires a remarkable moral stance. He advocates the freedom, responsibility, and autonomy of the subject, values that he assumes institutional psychiatry shuns. Yet this implies that, for Szasz, the patient appears in a totally different light. In place of the medical psychiatric criterion that in a certain sense declared the patient both innocent and helpless, Szasz now gives us a moral value judgment that very rapidly becomes a prejudice. The striking thing about his line of reasoning is that it enables us ultimately to align Szasz with someone like Slater (1961, 1965), who argued that hysteria does not exist and that hysterical symptoms, lacking biological foundation, are proof that the patient is healthy.

For Szasz, mental illness does not exist, but the associated behavior does. So-called psychiatric patients are people who avoid their responsibility, who make unjustified use of their sick role. Thus we find the following notable saying from this liberator of the mentally ill: “The facts are, that, in the main, so-called mad-men […] are not so much disturbed as they are disturbing; it is not so much that they themselves suffer (although they may), but that they make others suffer (Szasz 1976, p. 36). With this, Szasz not only distances himself from the vindicating effect of certain psychotherapeutic theories (the subject is himself responsible for his behavior and has to assume this responsibility), but goes a considerable step further (if they don’t assume their responsibility, they are “disturbing mad-men”). Finally, we encounter here an accusatory prejudice that returns us to the idea of simulations, infantile adults, even criminals. Psychopathological labels are turned into pseudo-scientific excuses to “punish” “deviants,” a process that is not all that rare in the psy-enterprise. Already in 1939, Hartmann noted that his colleagues had no difficulty claiming “that those who do not share our political or general outlook on life are neurotic or psychotic.” That this still happens today is well known.

Aspiring toward the S1: The Appeal to the Primal Father

In the Discourse of the University, the other is turned into an object of knowledge, forcing the subject to feel its subjectivity more than ever as the product of such a de-subjectivizing approach. This discourse is supported by an underlying master signifier that serves to guarantee the discourse’s accuracy.24 In the anato-pathological approach, we could locate the paradigmatic discovery of dementia paralytica in this place, which has been replaced by behavioral genetics today. In the clinical-psychological-moral approach we see this function become personalized: the guarantee becomes embodied in a specific master-figure. Just as “made in Germany” guarantees quality, “Mr. X has said that…” certifies its truth.

In itself, this is a very interesting arrangement and a direct confirmation of Lacan’s interpretation of the Freudian Oedipus complex. The father as a guarantee can only function by grace of a super-father, a primal father. While Freud believed this to be historical reality, for Lacan it is a neurotic illusion: there is no “big Other” founding “the Other” although in itself this hasn’t prevented both Freud and Lacan from being installed or even installing themselves in the position of the master signifier S1.

Such a personification of the university discourse’s underlying guarantee has far-reaching consequences: the guarantee is not so much given by the master’s theory as by his or her associated ideology. This is easier to see in the field of clinical psychology because the problems it treats are indeed moral problems.25 It will become more visible still once we go from diagnosis to treatment—which is, after all, the aim of psychodiagnostics.

With regard to treatment, we encounter an ostensible opposition: either one strives for a completely objective approach—which is impossible—or one goes in the opposite direction and the therapist becomes the new Messiah, or meaning provider. Both approaches presuppose a master-figure in the form of the therapist who both knows and is able to instruct his patients in how psychologically normal people behave. A third possibility—that of abstinence (cf infra)—is entirely overlooked.26 Abstinence means that, in an attempt to handle this division differently, the therapist avoids imposing her desire onto the other and creates a situation in which the subject’s own subjectivity and accompanying division can be taken into account.

Where this does not happen, diagnosis and the cure become an authoritative form of help in which the therapist wants “the best” for his client. This best, however, implies a value judgment and, hence, can only ever be arbitrary: thus homo mensura must call upon a “superhomo supermensura.” Here we find the same deadlock as in the biological approach, where the underlying dualism between psyche and soma inevitably gives rise to an internal dualism, namely, the homunculus theory: someone has a headache because a smaller person in his brain has a headache, which is caused by an even smaller person in his even smaller brain, and so on.

The foundational master signifier S1, the Other of the Other, continues to recede ever further toward the horizon. Some idea of the danger of benevolent therapeutic help can be given by a Lacanian saying. He scans it in three bars that each time delineate the enclosed problem more sharply: “It is a fact of experience that what I want is the good of others in the image of my own. That doesn’t cost so much. What I want is the good of others provided that it remains in the image of my own. I would even say that the whole thing deteriorates so rapidly that it becomes: provided that it depends on my efforts.” (Lacan 1992 [1959–1960], p. 187). Here we can turn to Freud who, not coincidentally in a paper on transference, categorically dismissed such an attitude, precisely because “psycho-analytic treatment is founded on truthfulness” (1978 [1915a], p. 164) by which he simultaneously recognizes its greatest ethical value.

Nostalgia for the Father

This issue has become all the more problematic as a result of the social evolution of attitudes toward authority. Roughly speaking, for half a century the overly severe father has been regarded as the cause of every psychopathology in his children: the patriarch, the leader of the primal horde who raised his children into neurotically contorted milksops. The sexual revolution, antiauthoritarian models of upbringing, learning-in-freedom and Sommerville schools were all corrections to this, based on its opposite. Quantitative criteria were used as well: an overly severe father causes frustration and neurosis in his children; an excessively severe monster-father goes a step further, causing psychosis in his offspring. Strangely enough, we hear pleadings, almost supplications today for the return of this father patriarch: “More structure!”…“the Name of the Father has to be installed!” A severe father might not be all that much fun, but an absent father is even worse. People talk more generally about the loss of the grand narratives, the myths: human beings need a meaning-bestowing belief in something, whether it is religion, politics, or…science. A final, desperate attempt to sit on the fence is found in the eternally returning quantitative logic: the father must be authoritarian, but not too much so.

Here, the moral treatment model turns into nostalgia for the primal horde: “Long before he was in the world…there was the father who knew that a Little Hans would come who…”27 The anato-pathological model has less need of this nostalgia because there the installation of the S1 seems more secure. From a psychoanalytic perspective, two comments can be made. First, this pleading for a return fails to make an essential distinction between the real father, the imaginary father image, and the symbolic function of the father. Second, with Lacan we can go beyond the Freudian call for the primal father-master (“You are looking for a master, you will find one”)28 as a typically neurotic and perpetually failed solution to one’s own self-division; the failure is inherent in the structure of the Master discourse itself. This is not to say that this type of solution is not exercised just as much in science (deus sive natura), in politics (Papa Stalin and Co.), and in religion (from the Pope to Khomeini) as on the individual-clinical level.

The application of the two paradigms, the savoir-faire (know-how) of both medical and psychological practice, is nothing but a phenomenalization of the University discourse. To found a practice upon this demands the politics of the ostrich. Without awareness of that one is confronted with impossibility and impotence. In our field, this can be seen in Freud’s concept of the “impossible professions”: educating, governing, analyzing. Nor did this stop his own theory from being turned into a paradigm in a very short time as well.

THE ANALYTIC PARADIGM: PROMISE AND DECAY

Freud’s originality lies in his daring originality. This tautology can be found at the origin of every scientific innovation: every time someone risks leaving the beaten path, the chance of something new appears. The associated paradox is that, following this fruitful side track, a group of disciples emerges to defend the master’s orthodoxy. Anything is allowed, so long as it is written by the master. In the name of an original thinker, originality itself becomes forbidden.

Before examining the psychoanalytic paradigm, I will first explain Freud’s original vision of psychopathology, for which a well-known expression can serve as a guide: the flight into health. Next we will look at Freud’s own evolution, which, starting out from a positive scientific model and colliding with its deadlocks, inevitably culminated in certain ethical implications. Moreover, it will become clear that this ethic was implicitly present from the beginning despite its being hidden under the various different names of objectivity. Finally, we will be able to pinpoint the moment when, after Freud, this decay into an “analytic paradigm” occurred.

Freud: The Flight into Health

One reproach often leveled at psychoanalysis is that it makes any behavior suspect, constantly shifting the border between what is normal and abnormal. This reproach has to do with Freud’s expansion of the concept of the symptom; from an analytic perspective, anything that can be traced back to the history of a subject’s formation is a symptom. Such a statement says nothing about the pathological or normal character of this symptom, only about its place, signification, and function within the economy of a particular subject. Israel (1984) expressed this position in terms of a wish: that one day a diagnostics independent of all pathological connotation would emerge.

The reproach, therefore, doesn’t go far enough. Freud didn’t so much shift the frontiers between normality and abnormality as explode them. The “flight into health” of our title can serve as a paradoxical leitmotif here. We encounter it, for instance, in a case study of obsessional neurosis (1978 [1909d]), where it refers to what is no doubt quite a remarkable process: the patient recovers in order to escape from the truth that is on the brink of emerging through the analytic process. In his paper “On Beginning the Treatment” (1978 [1913c], Freud uses the metaphor of the set of scales: on the one side is the loss, namely, the subjective pain caused by the symptoms; on the other, the gain, the primary and secondary advantage of the illness. This balance as fully determines the moment when someone appeals for treatment as when they stop it.

This is, incidentally, common knowledge for every clinician: the moment that someone asks for help is almost never contemporaneous with when the symptom started. Typically, the pathological structure is much older, while the demand for help almost always seems to come too late. This is the most important starting point for the intake sessions: Why has the patient come now, at this specific moment? To put it differently, what has changed in the symptom’s balance sheet of gains and losses that makes a demand for help needed now? At the same time, the equivocal quality of many demands for help becomes transparent: most patients want nothing more than a restoration of the original balance, not the dissolution of the structure—this is evident from another Freudian case study, this time concerning a hysteric (1978 [1905e]). Hence the consultations will be stopped once the balance is restored, while nothing has fundamentally changed—this, then, is the flight into health. Its opposite is still more paradoxical: the therapeutic negative reaction, in which the analysis runs beautifully, but the patient suffers even more profoundly. The revelation of too much truth is not always easy to take, and it is not by chance that Lacan puts an ethical imperative at the foundation of the analytic process and of the unconscious: “Whatever it is, I must go there” (Lacan 1994 [1964], p. 33).

The subversion of health into illness suggests a fundamentally different vision of psychopathology in general, and of the symptom in particular. After psychoanalysis, it is well known that a psychopathological symptom is an attempt at cure, more specifically, an attempt to reach a solution within a given psychic structure. This still revolutionary idea is in fact age-old as it perfectly reflects the Hippocratic view of illness (as discussed above): illness is an organism’s healthy reaction to an imbalance, a reaction that normally ends in health. Its accompanying symptoms are attempts to adapt to it. In the first half of the twentieth century this mechanism was even reversed. A psychosis? No problem. Transform it into malaria and the psychosis will vanish (known as the “Von Sackel” treatment). It is almost like the implicit rule of folk psychology: solve a problem by creating a bigger one.

Back to Freud then. His explosion of the border between the normal and the abnormal can be seen at any number of points. It is enough simply to consult the index of the German Gesammelte Werke under “Normal” and “Normale Menschen.” It extends over ten columns, and we encounter just about every pathological phenomenon.29 His foundational texts present the same combination every time, from The Interpretation of Dreams to The Psychopathology of Everyday Life and Jokes and Their Relationship to the Unconscious: there is practically no difference between the “healthy” and the “sick” mind. It is not by chance, moreover, that this intermingling occurs; it takes on an increasingly structural importance throughout the development of Freud’s theory, as can be illustrated through three main themes.