5. The Mongol Invasion of 1241 and its Consequences

“In this year, after existing for 350 years, the kingdom of Hungary was annihilated by the Tatars.” This terse statement by the Bavarian monk Hermann of Niederaltaich appears in the annals of his monastery for the year 1241. At almost the same time, the Emperor Frederick II wrote to the English King: “That entire precious kingdom was depopulated, devastated and turned into a barren wasteland.” Contemporary witnesses and chroniclers still called the Asiatic attackers “Tatars”, although these already identified themselves as Mongols.1

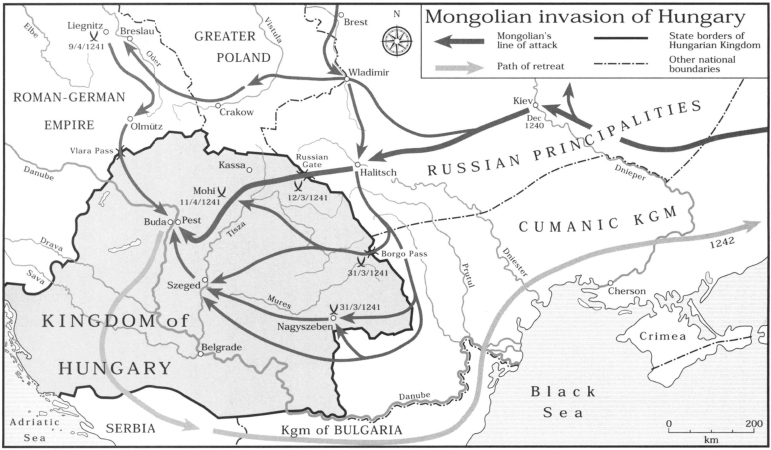

The “Mongol storm” had been in progress in Asia and Eastern Europe for half a generation, buffeting Russians, Cumans and Poles, yet Hungary was the first to be hit with full force by Genghis Khan’s successors. On 11 April 1241 at Mohi by the confluence of the Sajó and Hernád rivers, the Mongol horsemen led by Batu Khan annihilated the numerically superior but ill-led and barricaded Hungarian forces. Amid indescribable chaos the majority of the country’s religious and lay dignitaries were slaughtered, and it was as if by a miracle that the king and some of his young knights escaped. The Mongols followed in Béla’s tracks as far as Klosterneuburg, near Vienna, and finally even besieged the Dalmatian island city of Trogir, where he had taken refuge: in the Mongols’ eyes a country was not definitively vanquished while its rightful ruler still lived. For months the siege of Trogir continued, and the king and with him Hungary—indeed probably the West itself—were only saved by the sudden death of the Great Khan in far-away Karakorum. When this news reached Batu Khan in the spring of 1242, he promptly turned his Mongols around to be present at the contest for the succession. They pulled out of Hungary, laden with plunder and numerous prisoners: even thirteen years later, the missionaries Carpini and Rubruquis, travelling through the region of Karakorum, met Hungarian slaves still in bondage.

The Mongol storm resulted in a deep disruption for the Magyar population from which, according to medievalists such as György Györffy, Hungary never completely recovered. Györffy calculated that some 60 per cent of the lowland settlements were destroyed. The inhabitants who survived the massacres and abductions were threatened by starvation and disease. Failed harvests caused by destruction of the fields and the impossibility of tilling them added to the catastrophe. The situation was somewhat less severe in the regions west of the Danube, as these were only plundered and torched during the Mongols’ advance and never occupied; here the population loss amounted to about 20 per cent. The Slavs of Upper Hungary as well as the Székelys and Romanians of the Transylvanian mountains had come off fairly lightly. In all, according to older estimates, about half of Hungary’s 2 million inhabitants in 1240 became direct or indirect victims of the Mongol invasion.2

The attack did not take Béla IV by surprise since he, alone in Hungary and perhaps in all the West, had recognized the deadly danger posed by the Mongols’ obsessive expansionist dreams of world domination. Owing to its still existing relationships with the Russian principalities, Hungary was quickly informed of events in the East, including the ruinous defeat of the Russians and Cumans by the nomad horsemen in 1223. Moreover, while still crown prince Béla had despatched a group of Dominican monks to the East in order to convert to Christianity the Hungarian tribes who, according to tradition, had remained in the old homeland; in his search for Magna Hungaria, the land of the early Magyars, Friar Julian actually came across people beyond the Volga with whom he could communicate in Hungarian, and it was from these “relatives” that he heard of the Mongols’ unstoppable westerly advance. After their return in 1237 one of the friars wrote an account of his travels and sent it to Rome. When Julian set out a second time on his adventurous journey to the East to scout out the Mongols’ intentions, he could no longer reach the ruined homeland of the distant tribesmen, who had by then been overwhelmed. Julian hurried back to Hungary with the terrible news and accurate information about the Mongols’ military preparations. Furthermore, he brought a threatening letter from Batu Khan to King Béla, calling upon him to surrender and hand over the “Cuman slaves” who had taken refuge in Hungary. Béla did not reply to the ultimatum. However, unlike the Pope and the Emperor, who had for years been entangled in a controversy over the primacy of Rome, the King took the Mongol threat seriously, being fully aware that if the charges and demands were ignored by those threatened, a devastating campaign would always follow.

Béla IV therefore suspected what was in store for his country, and prepared for battle. He personally inspected the borderlands, had defence installations prepared on the mountain passes, and tried to assemble a strong army. It was not his fault that, despite these precautions and warnings to the Hungarian nobles, and appeals to the Pope, Emperor Frederick II and the kings of Western Europe, the Mongols descended upon Hungary and wrought devastation following their victory at Mohi. Though intelligent and brave. Béla was not a general and did not have a powerful professional army at his disposal. Even before his father’s Golden Bull the nation’s warriors, formerly ever ready for battle, had become “comfortable landowners”3 and were no longer a match for the Mongol hordes operating with remarkable precision and planning.

Another factor was present, with consequences hardly ever considered by Western historians with no knowledge of the Hungarian language although it had decisive consequences already in the earliest days of the Hungarian state, and contributed to other great disruptions in the nation’s history—defeat by the Ottomans and Habsburgs. This factor was an ambivalence towards everything foreign. Oscillation between openness and isolation, between generous tolerance and apprehensive mistrust was probably the main cause of the essentially tragic conflict with the ethnic group which would eventually form the backbone of the Hungarian army: the Cumans. Although this Turkic people had repeatedly attacked Hungary in the past, they later sought refuge and support from the Magyars, especially in view of the unstoppable advance of the Mongols. While still crown prince, Béla endorsed the Cumans’ conversion by the Dominicans and accepted the oath of allegiance of one of their princes who converted together with 15,000 of his people—a bishopric was established for these so-called “western” Cumans. Ten years later the “eastern” Cumans also fled from the Mongols across the Carpathians, giving Béla the support of another 40,000 mounted warriors against the impending invasion from Asia. Before admitting them he had them baptized, yet the integration of this nomad people into the by then Christianized and westernized Hungarian society led to tensions and rioting. When the Mongol offensive was already approaching, the distrustful Hungarian nobles attacked and murdered the Cuman Prince Kötöny, whereupon his soldiers, swearing vengeance, took off to Bulgaria leaving in their wake a trail of carnage and destruction. Thus four weeks before the crucial battle at Mohi the King lost his strongest allies.

The same groups of nobles who had aggravated existing tensions in the early phase of the Cumans’ assimilation then complied only hesitantly and reluctantly with the king’s appeals to be in readiness with their contingents. In their accounts the two important witnesses of the Mongol onslaught, Master Rogerius and Thomas of Spalato, revealed clearly the profound differences between the king and a section of the magnates. According to a contemporary French chronicler, Batu Khan heartened his soldiers before the battle of Muhi with the following derogatory slogan: “The Hungarians, confused by their own discords and arrogance, will not defeat you.” The barons, as already mentioned, were incensed mainly by the fact that Béla sought to withdraw his father’s prodigal donations, and that he overrode their opposition in bringing the Cumans into the country and then giving them preferential treatment. They even spread the rumour that the Cumans had come to Hungary, as the Mongols’ allies, to stab the Hungarians in the back at the first opportunity.

The Italian cleric and chronicler Rogerius, who lived through the Mongol invasion, saw this differently. He praised Béla IV as one of the most notable of Hungary’s rulers, who had done a great service to the Church by his missionary work among the pagan people: he had tried—as they deserved—to subdue the “audacious insolence” and insubordination of his barons, who did not balk even at committing high treason. Rogerius defended Béla against the accusation of not having taken steps in time to avert the danger from the Mongols. On the contrary, the nobles had been urged early and repeatedly to gather their regiments and rally to the King. Despite Béla’s obvious inability to impose order on the army, Rogerius blamed the nobles whose antagonism to the King not only denied him vital support in the battle, but virtually willed his downfall—“because they thought that the defeat would only affect some of them and not all.”

Added to the mistrust of foreigners and the discord within their own ranks was the indifference of a silent Western world. The priestly chronicler accuses the European princes of failure to answer the Hungarian King’s calls for help; none of Hungary’s friends had come to its aid in its misfortune. Rogerius does not exclude even the Pope or the Emperor from blame; all had miserably failed. In a letter to Pope Vincent IV Béla wrote in 1253: “We have received from all sides…merely words. […] We have received no support in our great affliction from any Christian ruler or nation in Europe.” The Mongol nightmare determined, consciously or unconsciously, not only the King’s exchange of letters with the various popes and potentates, but also his foreign policy. By far the most important and lasting psychological consequence of the Mongol invasion was the inference “We Hungarians are alone”. The sense of isolation, so characteristic of Hungarians, hardened from then on into a “loneliness complex” and became a determining component of the Hungarian historical image. The calamities of the sixteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries set this reaction into concrete.

Fear of a second Mongol invasion was bizarrely echoed even in King Béla’s dynastic policy. He wrote in a letter to the Pope: “In the interests of Christianity, we let our royal dignity suffer humiliation by betrothing two of our daughters to Ruthenian princes and the third to a Pole, in order to receive through them and other foreigners in the East news about the secretive Tatars.” Clearly an even greater sacrifice, mentioned in the same letter, was the marriage of his firstborn son to a Cuman girl; this was supposed to bind the warlike nomad horsemen, called back a few years after the Mongol attack to the depopulated areas of the Danube-Tisza plains, even closer to the House of Árpád, and hasten their absorption into the Western Christian community.

The aversion to foreigners, even when they were urgently needed as allies; the friction within their own ranks, even in times of extreme danger; and finally the justified sense of aloneness and being at the mercy of others, formed the background to the first catastrophe in the history of the Christian Hungarian kingdom. That the Hungarians felt misjudged, betrayed and besieged by enemies was probably also, or perhaps primarily, the result of what is unanimously criticized in international historiography as “brazen blackmail”. The Austrian Babenberg Duke, Frederick II, set a trap for the fleeing King of Hungary (his cousin and neighbour, not to be confused with the Hohenstaufen Emperor) robbed and imprisoned him. The Austrian was already nicknamed “the Quarrelsome” because he had fallen out with most of his neighbours, even having been temporarily outlawed and divested of his fief in 1236 by the Emperor.

Rogerius, who—as mentioned above—had lived through the Mongol invasion as an eye-witness and was himself imprisoned for a year, described this deed in the thirty-second chapter of his account:

After his flight from the hordes the King rode day and night until he reached the Polish border region: from there he hurried, as fast as he could, by the direct route to the Queen, who stayed on the border with Austria. On hearing this the Duke of Austria came to meet him with wicked intentions in his heart, but feigning friendship. The King had just laid down his weapons and, while breakfast was being prepared, lain down to sleep on the bank of a stretch of water, having by an act of divine providence made his long escape alone from many horrible arrows and swords, when he was awakened. As soon as he beheld the Duke he was very happy. Meanwhile the Duke, after saying other comforting words, asked the King to cross the Danube, to have a more secure rest on the opposite bank, and the King, suspecting no evil, consented because the Duke had said that he owned a castle on the other side where he could offer more befitting hospitality—he intended not to entertain the King but to destroy him. While the King still believed he could get away from Scylla, he fell victim to Charybdis, and like the fish that tries to escape from the frying pan and jumps into the fire, believing that it has escaped misfortune, he found himself in an even more difficult situation because the Duke of Austria seized hold of him by cunning, and dealt with him according to his whim. He demanded from him a sum of money which he claimed the King had once extorted from him. What then? The King could not get away until he had counted out part of that money in coin and another part in gold and silver vessels, finally pledging three adjacent counties of his kingdom.4

According to Rogerius, Duke Frederick robbed the Hungarian refugees and invaded the defenceless country with his army. He even attempted to capture Pressburg (now Bratislava) and Györ, which however managed to defend themselves. The chronicler did not realize that Duke Frederick II and Béla IV had old scores to settle. Frederick had attacked Hungary several times since 1233, and had supported an uprising by Hungarian magnates against their King. When András II and his sons. Béla and Coloman, resisted and chased him back to Vienna, the duke could obtain a peace agreement only in return for a costly fine. He had never forgotten this humiliation, and now, against the admonitions of Pope Gregory IX, exploited the Hungarians’ desperate situation.

The historian Günther Stökl referred to the “understandably very negative impression” which “the treachery of its western neighbour left in Hungarian historical consciousness”.5 As is well-known, none of the Central and East European states have school textbooks that treat in a particularly balanced way their own and their region’s history. Still, the chasm is rarely as wide as in the depiction of the episode described by Rogerius. Thus the Hungarian historian Bálint Hóman (1935): “Frederick… capped the disgraceful offence against the right of hospitality to the greater glory of Christian solidarity with an attack on the country suffering under the Tatars.” The Austrian historian Hugo Hantsch (1947) saw the role of the Babenberg Duke differently: “Frederick… stops the Tatars’ advance to Germany… Austria once again proves its worth as the bulwark of the Occident, as the shield of the Empire.”

It was an irony of fate indeed that the moribund kingdom was successful against the expansionist attempts of Duke Frederick of Austria in particular. After Frederick’s death in the battle at the Leitha in June 1246 Béla even got involved in the succession struggle of the Babenbergs and brought Styria temporarily under his control, his son and successor becoming its prince for some years. However, after a serious defeat by Ottokar II of Bohemia at Marchegg in Austria, the Hungarians were no longer able to assert themselves. The “annihilation of the kingdom of Hungary”—the laconic diagnosis of the Bavarian monk quote at the beginning of this chapter—never actually came to pass. On the contrary, Béla IV steeled himself after his return for the enormous task of rebuilding the ravaged country, especially the depopulated lowland and eastern areas, which he did with considerable energy, resolve and courage.

Béla, not unjustly dubbed in his country as its second founder after St Stephen for his statesmanship and achievements, still had twenty-eight years ahead of him after the departure of the Mongols. Like Stephen, he was a ruler who practised openness, and the prime mover in an extensive policy of colonization. His realm extended over the entire Carpathian basin and embraced Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia and part of Bosnia. The reason why he so quickly regained his political power is partly that the most densely populated western areas of the country were those least affected by the Mongol depredations. Still, his entire domestic and external politics were always haunted by the nightmare of a renewed Mongol incursion, which led to the organizing of a completely new defensive system. The fact that only some castles had withstood the Mongol attacks showed that only well-built forts offered genuine security. That is why the King wanted to see so many cities and smaller places encircled by stone walls. He created a new powerful army, replacing the light archers with a force of heavy cavalry.

Béla managed to resettle the Cumans on the Great Plains, and this foreign tribe came to play an outstanding role in the new army. In his previously cited letter to Pope Innocent IV he wrote: “Unfortunately we now defend our country with pagans, and with their help we bring the enemies of the Church under control.” The Alan Jazyges, originally also steppe horsemen from the East, settled in the country with the Cumans. A royal document of 1267 states that the King had called peasants and soldiers from all parts of the world into the country to repopulate it. German colonists as well as Slovaks, Poles and Ruthenes thus came into Upper Hungary (today’s Slovakia); Germans and Romanians, but also many Hungarians, moved to Transylvania. Soon French, Walloon, Italian and Greek migrants moved to the cities. The Jewish communities of Buda (newly fortified as a royal seat), Esztergom and Pressburg were under the King’s personal protection. Already by 1050, according to the Historical Chronology of Hungary by Kálmán Benda, Esztergom was a centre for Jewish traders who maintained the business connection between Russia and Regensburg and are said to have built a synagogue. Minting was assigned to the archbishopric of Esztergom, which in turn entrusted the task to a Jew from Vienna named Herschel.

King Béla finally had to pay a high political price to the predominantly narrow-minded, selfish oligarchs for the surprisingly fast reconstruction, the promotion of urban development and—his priority—the establishment of a new army. The disastrous concentration of power in the hands of the great magnates remained in force, and in stark contrast to Béla’s radical measures and the reforms passed before the Mongol attack, they were able to assert their old privileges and, even more serious, they were not after all required to return the royal estates and castles, but even received further endowments. This soon created chaotic conditions.

During the last decade of his reign Béla was already embroiled in a serious conflict with his son, the later Stephen V, who was strong in military virtues but power-hungry. Stephen’s rule as sole king lasted only two years; he could not control the mounting tensions between the power of the oligarchs—who by now were feuding among themselves, as were some of the senior clergy—and the lower nobility, who had been supported by Béla as their counterbalance through the granting of privileges. But it was the particularly explosive and unresolved issue of the absorption of the Cuman horsemen into the Hungarian environment which once again impinged disastrously on the royal house itself. Although the Cumans were a mainstay of the new army, especially in campaigns outside Hungary’s borders, the complete socio-religious and linguistic assimilation of the tens of thousands of former nomad horsemen took another two to three centuries.

The marriage of Béla’s son Stephen to Elizabeth, daughter of the treacherously assassinated Cuman prince Kötöny, was meant to seal a lasting reconciliation with this ethnic group. The plan was to give the Cumans parity of treatment with the nobility, but Stephen’s untimely death brought an abrupt end to these endeavours.

Stephen’s son Ladislaus IV (1272–90) was still a child, and the Queen Mother Elizabeth, who called herself “Queen of Hungary, daughter of the Cuman Emperor”, proved to be a puppet in the hands of the power-hungry oligarchs and blatant favourites, and thus totally unfitted for the task of regency. She and her son trusted only Cumans, hindering rather than fostering the precarious process of integration by their exaggerated and demonstrative partiality towards the steppe warriors.

Only once did the young King Ladislaus IV show his mettle—by a historic action at a decisive moment for Austria’s future. It happened on the battlefield of Dürnkrut, where the army of Hungarians and Cumans, estimated at 15,000 men, resolved the conflict between Rudolf of Habsburg and Ottokar II of Bohemia. In the words of the Hungarian historian Péter Hanák, “In the battle of the Marchfeld [Dürnkrut] Hungarian arms helped establish the power-base and imperial authority of the Habsburgs.” Apart from this, the life of the young King, already known in his lifetime as “Ladislaus the Cuman” (Kún László), was an uninterrupted series of scandals, intrigues and bloody settling of scores. The passionate, spirited and, according to tradition, continuously love-struck King for some reason refused to produce a successor with his wife, the Angevin Princess Isabella of Naples, and had her locked up in a convent. When his pagan following and numerous mistresses resulted in a papal interdict, the psychopathic monarch threatened (as the Archbishop expressed it in a letter to the Pope) “to have the Archbishop of Esztergom, his bishops and the whole bunch in Rome decapitated with a Tatar sabre”. Incidentally, Ladislaus IV is supposed to have performed the sex act with his Cuman mistress during a Council meeting in the presence of the dignitaries and high clergy. He was excommunicated, and finally killed at the age of twenty-eight by two Cumans hired by the Hungarian magnates.

Ladislaus died without issue and anarchy followed. Groups of oligarchs ruled their spheres of interest as if they were family estates, and considered the entire country theirs for the taking, dividing it up between themselves. The last Árpád king, András III, was unable to re-establish central authority or prevent the country’s disintegration. He died in 1301, leaving only an infant daughter, and with him the male line of the Árpáds died out. Years of struggle for the coveted throne of Hungary, by now recognized as a member of the European community of states, resulted in 1308 in the victory of the Angevin Charles Robert, grandson of Mary of Naples, sister of Ladislaus IV.

In the long run the politically and, above all, psychologically most significant heritage of the time of “Ladislaus the Cuman” was the “new historical image” of the Hungarians, invented from A to Z by his court preacher Simon Kézai. In his famous letter to the Pope, King Béla still compared the Mongols with Attila and his murderous and fire-raising Huns. Barely a generation later, between 1281 and 1285, the grandson’s court scribe saw the Huns in a quite different light. Kézai, a gifted storyteller, perceived Attila as a worthy ancestor of the Christian kings. From sources he found “all around Italy, France and Germany” this court cleric, a man of simple background, calling himself in his preface an enthusiastic adherent of King Ladislas IV, concocted the evidently desired historical image. He produced the surprising theory of a “Dual Conquest”: the original 108 clans had in the distant past already made up the same people—who at that time were the Huns, and were now the Hungarians. Coming from Scythia, they had already occupied Pannonia once before, around the year 700, and under Attila conquered half the world. They then retreated to Scythia, finally settling permanently in Pannonia. The 108 clans of 1280 were thus, according to Simon Kézai, the descendants of the original community—without any mingling. Thus was born a historical continuity which had never existed.

This “inventive dreamer”, noted Jenö Szücs, supplied a historical, legal and even “moral” basis for the Magyars’ “historical right” to the Carpathian basin and for the resolute self-assertion of the lower nobility in their fight for existence in spite of the oligarchs. The ambitious petty nobility were akin to the will of the community of free warriors as the source of princely power. In his essay Nation and History Szücs6 destroyed the royalist cleric’s new national concept, which presented the nation of nobles as the buttress of legitimate royal power, threatened by the magnates. In contrast to Western interpretations, Kézai rehabilitated Attila and indeed the entire Hun era. One could easily shrug off these flights of fancy had they not determined the historical self-image of the Hungarian nobility and national historiography well into modern times. Ladislaus Rosdy, the Austro-Hungarian publicist, stressed in an essay on Hungary the alarming long-term effect of this historical fiction, which had virtually become common property:

In all this time there have not been any Hungarians—apart perhaps from a critically-minded minority well educated in history—who have not been convinced by Master Kézai’s obviously falsified Hun saga; and even among the otherwise sensitive Hungarian poets of the twentieth century there are many who proudly keep up this tradition, which in reality is no more than the expression, by the “last of the Nomads”, of superiority mixed with resignation.7

The theory of the “Dual Conquest” was the spring from which historians, scientists and national politicians have drawn at their convenience. The romantic and heroic character of the Hun saga as told by Anonymus and especially by Kézai held an almost irresistible attraction for generations of politicians and writers, the intensity of which is to this day admitted only in secret. Even Count István Széchenyi, the statesman criticized for his qualified royalist sentiments, wrote in his diary on 21 November 1814:

It is proof enough of the fact that I come from the truest race of the Huns that I can never feel as emotional, expansive and enthusiastic in the most beautiful Alps of Switzerland, or fertile valleys and areas of Italy as in the empty plains of my fatherland. […] I have a quite unusual passion for those cataclysmic, devastating wars. […] One of Attila’s innumerable horsemen, with whom he laid waste every country, seems according to my own mood, if I dissociate myself completely from all culture and logic, to have been a very happy man.8

These words, published only decades after the suicide of Széchenyi, whose career and role are discussed in detail later, give a most revealing picture of the Hungarian psyche. They show the extent to which freedom, courage and soldierly virtues are valued as Hungarian attributes, while others, such as tolerance and political wisdom, demonstrably qualities of most of the Árpád kings, are often over-looked. Be that as it may, it is no exaggeration that there are few nations (perhaps the Serbs come to mind) to which Ernest Renan’s words “No nation [exists] without falsification of its own history” are more pertinent than Hungary.