Chapter 35

Less than six weeks later, on the day before the grand reopening of Clay Home for Veterinary Services, a passerby might have startled at the strange grunts, bumps, groans, and creaks emanating from the open windows of the house known as Clay Manor. This stranger might then jump, hearing a cheerful voice from the garden, only to see Mrs. Emily Perkins, founder of the New Collective School, waving cheerfully with a garden spade.

And then, a moment later, the door would burst open, and Cornelius Clay would emerge to cart a ratty armchair to the growing stack of furniture on the corner, earmarked for the dump. Or a sweet-looking girl with an unfortunate haircut would float by in one of the windows, holding a paintbrush and complaining that Gregory, whoever he was, had chosen the wrong color.

And the passerby would hurry on, embarrassed for having been caught spying.

The same scene had been replayed for many weeks. Since late January, Clay Manor had been full of the drumming of feet up and down the stairs, shouted conversation, and furniture bumping through the doorways. The rhythm of a hammer was almost constant, as was the rhythmic shush of paint on the walls. And laughter. Almost always, laughter.

What was missing from Clay Manor were the screeches and squawks, the wailing, the animal grunts and growls.

What was missing, in fact, were the monsters.

“I still don’t see why you had to give them up,” Gregory grumbled, even as Cornelius and Cordelia wedged a dresser into the corner of his new room. The walls had been patched and painted sky blue. The floors repaired and refinished. No one would guess that mushrooms had ever grown in the corner.

“You still have Cabal,” Cordelia pointed out.

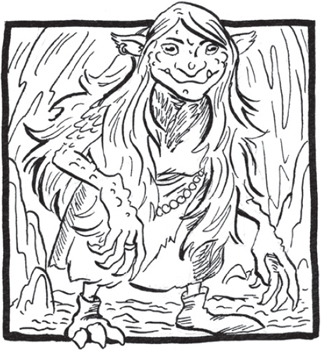

“Cabal’s different,” Gregory said dismissively. Down in the garden, Cabal began barking, as if he’d overheard and taken offense. Cordelia went to the window and watched him rooting around the planting beds, while Mrs. Perkins’s husband tried to shoo him away from the beds. Elizabeth and her mother were kneeling side by side, carefully tamping down the earth around a trellis meant for climbing roses. The garden was already taking shape under their care. Goblins were known for their green thumbs. Literally.

“Professor Natter says you can visit Icky whenever you want,” Cornelius said, carefully centering a lamp on the dresser. The professor had come to visit not long after they’d escaped Plancke, and his bond with the filch, a double of his favorite childhood pet, was undeniable.

“But what about all the others?” Gregory said. “I don’t mind sharing a room with a squelch, even if it is molting. . . .”

“We miss the monsters too,” Cornelius said, laying a hand on Gregory’s shoulder. “But what we were doing—keeping them here, locked up in the house—it wasn’t right. Monsters belong to the world. They belong in the world. We had no right to keep them here.”

“But what if something happens?” Gregory persisted. “What if they get hunted down, or caged up, or—?”

“We can’t stop all the evil in the world,” Cornelius interrupted him. “We can only make sure we don’t repeat it. A cage is a cage, even if it has a roof. Even if you name it ‘protection.’ Now go on,” he added, tousling Gregory’s hair. “There’s still plenty to do before the grand reopening of Clay Veterinary. Especially since someone’s been spreading a rumor that I can perform miracles, like bringing dogs back from the dead. . . .”

“People say all kinds of twaddle,” Gregory said, flushing a deep red. “Come on, Cordelia.” He seized Cordelia’s hand and yanked her toward the stairs.

They slid down the polished banisters, Gregory’s favorite new trick, and landed with a soft thump on the new carpet that ran the length of the first floor hallway—all of it courtesy of the New Collective, a school founded by Mrs. Perkins for “project-based education and learning,” for students who did not fit traditional models of schooling. So far, forty-five people had enrolled for the fall, and while the ground floor would be dedicated primarily to Cornelius’s practice, the upper floors were slowly being converted into classrooms and project centers.

But the school’s heart, its center, its library, was almost complete.

Cabal was still barking, and Mr. Perkins was shouting something about his trouser leg.

“I’ll get him,” Gregory said. “Before he tries to sample blood straight from the source.”

“Good idea,” Cordelia said.

He dashed down the hall. Moments later, she heard the kitchen door wheeze open and bang shut.

She stood for a moment, enjoying the rare stillness. The rustle of paper made her turn. The windows were open in her mother’s former library, and a breeze turned the pages of the large books, open for display on the lower shelves.

She passed into the room, both familiar and unrecognizable. Gone was her mother’s desk. Gone was the crib. Gone were the heavy curtains. Sunlight spilled over the bookshelves, now filled with not only her mother’s collection of scientific treatises, but other books Mrs. Perkins had selected for the school—plays and poems, historical volumes, dictionaries, foreign language primers. Still, her mother’s first book was among them—and some of her collection of natural objects too.

Not the fossilized morpheus, though. They’d lost that during the scrum with Newton-Plancke.

But in the end, perhaps, it didn’t matter very much.

Cordelia moved to the glass-topped table at the center of the room, where the first bound copy of her mother’s now-finished manuscript, featuring an introduction and conclusion by Professor Natter, was proudly displayed. She turned again to the tree of life: a river of ink, flowing from a single source into dizzying rivulets of being, into everything that exists and has existed.

She placed a finger on the blank space, where the morpheus was meant to be.

It was funny, how the pattern was so clear, as soon as she was staring down the length of her finger. The veins of life on either side of it looked just like the pattern she’d seen cross-hatched in the fossil. Like you could twist them all together around her finger, and make a coil.

Two coils, actually. Each coil coiled, and coiled around the other. Like a double staircase, winding upward toward infinity.

Cordelia closed her eyes and heard her mother’s voice come in, carried by the wind, alive everywhere.