Digital Economies: The Challenges for Society

The digital revolution is rich in opportunities. Like it or not, this revolution is inevitable. All sectors of the economy will be affected. We have to anticipate the many challenges that the digital revolution presents so that we can adapt to them rather than merely enduring them: concerns about the trustworthiness of web platforms, data confidentiality, sustaining a health care system for all, fears about the destruction of work and greater unemployment, and the difficulties involved in implementing an increasingly complex tax system. These challenging questions underline the high economic stakes involved and the urgent need for a framework for analysis.

I start by discussing the need for Internet users to have confidence in the digital ecosystem. This trust must apply at two levels. As I showed in the last chapter, there is too much choice, too much information, too many people to interact with nowadays. Platforms are there to guide us and make up for our limited capacity to pay attention. This raises the question of the reliability of their recommendations. The second issue is the use made of personal data. This data is now a powerful economic and political asset for those who possess it. It will not always be used as we would wish, which raises the complex question of property rights over this data. Then I will explain why information could destroy health insurance systems, which are based on the mutual sharing of risks, and I will sketch out a regulatory response to this danger.

The digital revolution also raises fears about the future of employment and how it is organized: Which jobs are disappearing, or will disappear? Will there still be jobs once intelligent software and robots have been substituted for both skilled and unskilled workers? Will the jobs that remain be “Uberized”? Is society moving toward the end of conventional salaried employment, replaced by independent or “gig” labor? Any detailed predictions would prove wrong, so here I simply raise some of the main questions and try to provide elements of an answer.

TRUST

If we are already online through our computers, our smartphones, or our tablets, tomorrow the “Internet of things” (IOT) will make us even more connected. Home automation, connected cars, sensors (connected wristwatches, intelligent clothes, Google Glass), and other objects linked to the Internet will keep us constantly connected, whether we like it or not. This prospect inspires both hopes and fears. Whereas some of us now worry about cookies on our computers,1 soon public and private websites will have far more detailed profiles thanks to rapid progress in things like facial recognition software. It is natural under the circumstances to worry about constant surveillance, like Big Brother in George Orwell’s 1984. The social acceptability of digitization depends on us believing that our data will not be used against us, that the online platforms we use will respect the terms of our contract with them, and that their recommendations will be reliable. In short, it is based on trust.

TRUST IN RECOMMENDATIONS

In many areas, we depend on the advice of better-informed experts: a physician for our health, a financial adviser for our investments and loans, an architect or a builder for the construction of houses, a lawyer for wills and probate, a salesperson when choosing products. This trust can be built on reputation, as it is with a restaurant. We rely on customer ratings, our friends’ advice, or guide books. In the case of a neighborhood restaurant, if we are not satisfied we simply won’t go back. Reputation, however, forms a basis for trust only if the quality of the recommendation can be evaluated afterwards.2 If not, regulation may be necessary to improve the way the market functions.

Trust is linked both to competence and to the absence of conflicts of interest (such as sales commissions, friendships, or financial ties to a supplier). These conflicts of interest may lead the expert to recommend something not in our best interest. Just as the salesperson at the mall might recommend a particular camera or washing machine to get a bigger commission, it is reasonable to ask whether a website recommends products to suit our tastes and give value for money, or because it will get a share of the profits if we make the purchase. Nowadays, doctors are increasingly expected to reveal conflicts of interest, such as gifts or commissions from a pharmaceutical company that might lead doctors to recommend a less effective or more expensive drug, or to send us to an inferior clinic for treatment. In the future, the same problem will arise with medical apps on the Internet: Can they be both judge and judged? This problem is obviously not peculiar to medical services. More and more professions (including research) are subject to the requirement (whether imposed by law or self-imposed) to divulge potential conflicts of interest.

TRUST IN THE CONFIDENTIALITY OF PERSONAL DATA

We trust our doctor because he or she is bound by a vow of professional confidentiality that is almost always honored. Can we be sure that the confidentiality of the personal information collected by the websites and social networks we use will also be respected? The question of confidentiality is as important for digital interactions as it is for medical data, but the guarantees online are much weaker.

Websites do have confidentiality policies (which few people read); they tell us about putting cookies on our computers and try to be transparent. Nonetheless, the contract between us and the websites is, in the jargon of economics, an incomplete contract. We just cannot know exactly what risks we are incurring.

First, we cannot evaluate the quality of any website’s investment in security. Numerous recent examples, widely reported, show that this is not just a hypothetical issue: from the theft of credit card information (forty million Target customers in 2013, fifty-six million Home Depot customers in 2014, eighty million customers of health insurer Anthem in 2015) to the theft of personal information held by government agencies (in the United States, for example, the Office of Personnel Management in 2015, the National Security Agency in 2013, and even thirty thousand employees of the Department of Homeland Security and FBI in 2016), not to mention the sensational theft in 2015 of emails, names, addresses, credit cards, and sexual fantasies of thirty-seven million clients of Ashley Madison3 (a platform for extramarital affairs). Companies do invest large sums in online security to avert reputational damage, but would invest much more if they fully internalized the cost of such security breaches to their customers.

With the IOT, connected cars, household appliances, medical equipment, and other everyday objects will be partially or entirely managed remotely, and the opportunities for malicious hacking are going to increase. Though these technological developments are desirable, we must be careful not to repeat the mistake of constructing digital security for personal computers only in reaction to failures; security must instead be an integral part of the initial design of a device.

Moreover, clauses preventing the resale of customer data to third parties are unclear. For example, if a company transfers this data free of charge to its subsidiaries, who use it to provide us with services, has it broken our contract? The issue of data sharing is very sensitive. In general, any company that collects data should be at least partly responsible for any harmful use subsequently made of it by others, whether they obtained it directly or indirectly. (It is a bit like when a company’s first- or second-tier supplier pollutes the environment or exploits workers. The company at the top of the supply chain can be held responsible either through legal mechanisms, such as extended liability, or through reputational consequences.)

What happens to our data when the company holding it goes bankrupt? Online or offline, when a company is in default, creditors can recover part of their investment by acquiring or reselling its assets; this is how businesses get access to credit in the first place. If data is a major economic asset, creditors naturally want to exploit it. Is this transfer desirable if the company’s customers are relying on confidentiality? This too is not purely hypothetical: the American electronic products chain RadioShack had promised not to share its customers’ data, but this data was sold when RadioShack went bankrupt in 2015.4

An additional problem is that users do not always have the time and expertise to understand the consequences of a confidentiality policy whose implications are complex and sometimes seem remote (most young people who post photos and other personal information online do not think about the use that might be made of it when they apply for a job or a loan).

Thus, we might ask whether the “informed consent” that we give websites is genuinely “informed.” Just as in the case of commercial transactions offline, it is important to protect the consumer by regulation. When we park our car in a public lot, the ticket we take at the entrance specifies (legitimately) that entering the lot implies that we accept certain rules. We never read these tickets because it would be a waste of time and would block the entrance to the parking lot. But the law must protect us against one-sided clauses, that is, clauses that attribute disproportionate rights to the seller (such as the owner of the lot). The same goes online. Users cannot be expected to dissect complex documents every time they register with a website.

WHO OWNS DATA?

The processing of data will perhaps be the main source of value added in the future. Will we have control over our own data, or will we be hostage to a company, a profession, or a state that jealously retains control over access to it?

Today, many people are concerned about the entry of companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft into territories such as health care. This reaction (outside the US at any rate) is partly envy of the fact that one country, the United States, has been able to create the conditions for state-of-the-art research in companies and universities in areas such as information technology and biotechnology—the dominance of the United States and a few other countries is not just luck. Still, it is legitimate to worry about the barriers to entry facing other companies that do not already own large amounts of data in these sectors.5

Digital companies can use the data they have gathered about their customers to offer them more targeted, suitable products. In theory, there is nothing wrong with this (bearing in mind the point made above about the possible use of this data for purposes that were not part of the original deal). It is better to receive relevant than irrelevant advertising. The problem comes if would-be competitors cannot make similarly attractive offers because they do not have the same information; the incumbent with the data is in a dominant position and can increase its profits at the expense of the consumer.

This raises the following fundamental question: Does the company holding customer data have the right to make money from the possession of that information? The commonsense reply, also discussed in chapters 16 and 17, is that if the data was collected thanks to an innovation or a significant investment, then the company ought to be able to profit from retaining and using it. If, on the other hand, it was easy and cheap to collect, the data ought to belong to the individual concerned.

To illustrate this point, take the simple example of personal data entered by the customer of a platform, or by counterparties (consumer, seller) transacting on the platform. We are rated by the purchasers when we use eBay to sell goods, Uber drivers are rated by passengers (and passengers by drivers), and restaurants listed on TripAdvisor are rated by their customers. In these cases, there is hardly any innovation, because decentralized evaluation is natural, and commonplace online. Such data should belong to the user: we want to have the option of using a platform other than eBay if it raises its prices or provides inferior service, but we don’t want to start over again, without the reputation we laboriously built up for our eBay persona. Similarly, an Uber driver may want to transfer their rating when he or she leaves to go to work for Lyft. But the reality is different: from social networks to online stores, digital companies appropriate our personal data, albeit with our formal consent. Even health data garnered by implanted medical devices and Internet-connected wristwatches is usually transferred to the supplier’s website, which claims the property rights to it.

If there were a clear separation between data provided by the customer and the subsequent processing of the data, the right policy would be simple: the data should belong to the customer and be portable—that is, transferrable to third parties at the wish of the customer.6 Thus, since 2014, American patients have had access to their medical data, stored in a standardized and secure manner. Using an application called Blue Button,7 a patient can access his or her medical file and choose to share it with medical service providers. On the other hand, processing this data represents an investment on the part of the company, so that processed data should, in theory, become its intellectual property. It seems natural to draw a distinction between the data, which belongs to the individual users, and the processing of it, which belongs to the platform.

In practice, however, the boundary between data and processing can be hard to establish.

First, the quality of the data may depend on efforts made by the company. One of the major challenges for sites like Booking.com or TripAdvisor is to guarantee the reliability of data against attempts to manipulate it, for example by hotels employing people to post fictitious favorable ratings (or unfavorable ratings for competitors). Similarly, Google needs to ensure that its PageRank algorithm, which decides on the order in which links to sites appear onscreen (and which depends in part on their popularity) is not distorted by searches targeting a particular site in order to artificially boost its ranking. If there were no attempts to manipulate ratings on Booking.com, it would not really have any justification for claiming ownership of the hotel ratings data. It is only because Booking.com has invested heavily to improve the reliability that it cocreates economic value (the individual reputations of hotels) and can therefore claim a property right to it.

Secondly, the collection and processing of data may be connected. The type of data collected may depend on the use that will be made of the information. In this case, it is harder to draw a clear distinction between data—which belongs to the user—and processing—which belongs to the company.

People often argue that platforms should pay for the data we give them. In practice, many sites do pay. This payment does not take the form of a financial transfer, but rather of services provided free of charge. We provide our personal data in exchange either for useful services (search engines, social networks, instant messaging, online video, maps, email) or in the course of a commercial transaction (as in the case of Uber and Airbnb). Online businesses can often argue that they have spent money to acquire our data.

There is one other angle to the problem. The transfer of data from the company to the user (possibly to be sent to another enterprise, as with Blue Button) needs data portability standards. Who will choose which kinds of data will be assembled and how it will be organized? Could standardization stifle innovation? As data is at the heart of value creation, defining rules governing its use is an urgent task. The answer will be complex, and it must rest on careful economic analysis.

HEALTH CARE AND RISK

The health care sector provides a good illustration of the way digitization will disrupt business and public life in the future.

Health care data has always been created through contacts with the medical profession: in a doctor’s office, at the hospital, or in a medical laboratory. In the future, people will also be generating data nonstop, thanks to smartphone sensors or Internet-connected devices (as is already the case for pacemakers, blood pressure monitors, and insulin patches). Combined with knowledge of our genetic heritage, health data will be a powerful tool for improved diagnosis and treatment.

Big Data, the collection and analysis of very large data sets, presents both an opportunity and a challenge for health care. It is a marvelous opportunity insofar as it provides more precise diagnoses, which are also less costly because they limit the expensive time highly skilled medical professionals have to devote to each patient. Examinations and diagnoses will soon be carried out by computers. This frees the doctor and the pharmacist from routine tasks.

As in other areas, machines could replace human beings for some tasks. Compared with a human being, a computer can process a far larger quantity of a patient’s data and correlate it with the symptoms and genetic backgrounds of similar patients. A computer does not have human intuition, but this will gradually be overcome by machine learning, i.e., the processes through which the machine revises its approach in the light of experience. Artificial intelligence (AI), by imitating humans while also trying to discover new strategies, has enabled computers to dominate the game of chess for the past twenty years; in 2016, a computer defeated the world Go champion. Computer scientists and researchers in biotechnology and neuroscience will be at the heart of the value chain in the medical sector, and will appropriate a significant part of its added value.8 This may be speculative, but one thing is certain: the medical profession of tomorrow will not resemble the current one at all. Digital health care will improve prevention, which remains less developed than curative medicine. Technology might also help answer the question of how to provide equal access to health care, now endangered by the combination of higher treatment costs and weak public finances.

So the opportunities for society are magnificent. But so is the challenge to the mutuality and risk sharing that characterizes health care systems; let us first review the underlying insurance principles, which apply to all health care provision systems.

THE KEY PRINCIPLES OF THE ECONOMICS OF INSURANCE

The distinction between what economists call “moral hazard” and “adverse selection” is crucial here. Moral hazard is the common propensity to pay less attention, and make less effort, when we are covered by insurance and will not be fully responsible for the consequences of our actions. In general, moral hazard refers to behaving in ways that are harmful to others when we are not going to be held fully responsible: we leave the lights on or water our lawns too much when we aren’t paying the full costs. Another example is risk taking by a bank that knows it can always borrow more from lenders, when those lenders expect a government bailout if the risks don’t pay off. Yet another is an agreement between a company and an employee made to camouflage a dismissal as a termination, which in turn generates a right to unemployment benefits paid for by taxpayers.9 The examples could go on.

Some events, on the other hand, may not be our fault: the lightning that strikes our house, the drought that destroys our crops, a longstanding ailment or congenital illness, a car accident for which we are not to blame. We want to secure insurance against such risks, whose costs are best spread across the population. Such risk pooling may be limited, however, if different individuals face different probabilities of such a mishap, and if there are asymmetries of information about these probabilities. Insurers are accordingly concerned about the possibility that their offers attract risky insurees, but not low-risk ones, either because low-risk individuals self-select out of the market or because other insurers have “cherry picked” (attracted the most profitable insurees). For instance, healthy individuals may not want to pay the insurance premium appropriate to an average citizen, and therefore self-select out of the market; or well-informed insurance companies may offer lower premiums to these healthy individuals, denuding the market (to uninformed insurers) of all but those likely to experience poor health. When this happens, we say there is adverse selection in the market.

The principles guiding insurance for the common good are simple: risks that are not under the control of those concerned should be fully shared. When, on the other hand, people’s actions affect the risks, they must be held partly responsible, to give them an incentive to behave in the collective interest rather than only in their own interest. If an individual builds a house in a flood zone because the land is cheap, they should not get government support when the house is flooded.10 But the loss can rightly be fully covered if the damage is due to an unpredictable event. In health care, this principle means fully insuring the costs involved in treating a serious medical condition, but making patients act responsibly with regard to drugs or treatments with minimal therapeutic effects, or unnecessary consultations and tests.

In practice, things are a little more complicated. It isn’t always easy to distinguish the scope of moral hazard from that of bad luck, so we can’t be sure how far to hold people responsible: Was the harvest small because the farmer did a bad job, or because of unexpected problems with the soil or the climate? Do we get a second opinion from a doctor (imposing additional cost in countries with state health insurance) because we think the first doctor wasn’t sufficiently careful or competent, or because we are hypochondriacs?11

This inherent uncertainty about responsibility explains why (in any type of insurance) the insured and the insurer often share the risk. Deductibles are often used to achieve this. So, for example, in French health care, copayments established when the public health care program was first set up were high: 30 percent for a consultation, 20 percent for hospitalization. These copayments were then covered in full by supplementary insurance policies, so other copayments have been reintroduced to try once again to make patients share responsibility. Patients must now make minimum contributions to the cost of health care, though not on longstanding ailments, cancers, or other major health risks.12

TODAY …

Sometimes, the insurance market does not need to be regulated. Home insurance allows us all to pool our risks (if my house burns down, your insurance premiums will pay part of the cost of rebuilding it, and vice versa) without serious problems of risk selection: in other words, I can get a policy specifying a reasonable premium to insure my house because the chances that my house will burn down are about the same as the chances that your house will burn down.

This is not the case for health, where there are great inequalities among individuals. Without regulation, there would only be minimal risk pooling. There is a strong incentive for insurers to select “good” customers (those whose risk of illness is low). In France for example, half of all health care expenses are incurred for the treatment of only 5 percent of those insured. An individual with a longstanding medical condition will not find a private insurer prepared to sell health insurance at a reasonable price. (This question of preexisting conditions was an important issue in the US’s Affordable Care Act and the debate about replacing it.) The selection of risks—an insurer’s ability to target people with low risks and to offer them advantageous terms not available to riskier individuals—would generate huge inequalities, based solely on factors that individuals cannot control (the good or bad luck of being in good or bad health). Information kills insurance.13

That is why most of the world’s health care systems, whether public or private, forbid selection based on risk characteristics, at least for basic insurance (the US will be an exception if it reverts to the situation before the Affordable Care Act). In France, the public health care system is universal, so the problem of the selection of risks for basic insurance does not arise. In Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands, basic health insurance is provided by private businesses, who compete and are forbidden to cherry-pick insurees: they are not allowed to use questionnaires to identify less risky customers—they are in fact obliged to accept all potential subscribers. Their rates must be the same for everyone (although with variations allowed for a choice of deductible and sometimes based on age group). Of course, there are indirect ways of selecting low-risk customers who will probably have little need for medical treatment, for example by directing less advertising toward high-risk groups, but it is up to the regulator to intervene if there is abuse. In Switzerland, compensation for risks among insurers is also provided for; this further diminishes the incentive to select low-risk customers.14

The same may not be true for supplementary private health insurance. While other countries have chosen a coherent overall system—whether wholly or almost wholly public (as in the UK) or private (as in Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands)—France uses a hybrid system: public basic insurance with additional insurance coverage provided by the private sector. People therefore have two insurers, which doubles administrative costs and complicates the task of controlling medical costs. Furthermore, on the supplementary health insurance front, the French state encourages the selection of risks by subsidizing collective contracts provided through employment.15 Employees being, on average, in better health than the rest of the population, this works against the unemployed and the elderly, who are often forced to pay higher premiums to gain access to complementary insurance.16

The greater availability of information affects risk sharing. One of the positive aspects of this is that it will be easier to control moral hazard. Cheap monitoring of our behavior (such as the number of miles we drive, or our efforts to look after our health) will allow insurers to lower premiums and deductibles for those who behave responsibly. It will also enable them to recommend healthier behavior. On the other hand, the digitization of the economy and the progress of genetics, as exciting as they are, also create new threats to mutuality.

Genetic background is the typical example of a characteristic that is not subject to moral hazard: we do not choose it in any way, whereas we can, through our behavior, influence the probability of a car accident (by driving carefully) or the theft of our vehicle (by parking it in a garage or locking the doors). Without regulation, individuals whose genetic tests suggest that they will be healthy for the rest of their lives would be able to use these results to obtain cheap insurance. There’s nothing wrong with that, you’ll say … except that there is no free lunch. The cost of insurance for those whose genetic makeup suggests, on the contrary, a long-term malady or fragile health will see their insurance premiums rise to extremely high levels: farewell to mutuality and risk sharing. Again, information destroys insurance.

Prohibiting discrimination among customers based on genetics and health data is not enough to reestablish the mutuality that makes insurance possible. That is where the digitization of the economy can hurt. Our habits of consumption, our web searches, our emails, and our interactions on social networks reveal a great deal about how healthy our lifestyles are, and even perhaps about our illnesses. Twitter, Facebook, or Google, without having any access to our medical histories, can predict—approximately, to be sure—whether we have preexisting medical conditions, behave in risky ways, take drugs, or smoke. Digital companies can select people who are good risks very precisely by offering individualized or collective contracts based on the information they gather. Axa’s future competitors will probably no longer be called Allianz, Generali, or Nippon Life, but Google, Facebook, and Amazon.

We need to think about the future of insurance for health risks and plan for these developments, rather than merely endure them. This is a challenge for governments, but also for economists.

THE NEW FORMS OF EMPLOYMENT IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

NEW FORMS OF EMPLOYMENT?

Many people are concerned about the changing nature of work. This has some distinct aspects: the development of independent working, and the outlook for unemployment. It is difficult to forecast what the organizations or work of the future will look like, but the economist can contribute a few things to think about. Let us begin with the organization of labor.

Independent work is ancient: farmers, merchants, and many members of the professions are self-employed and usually own their means of production. Temporary workers, freelance journalists, performers, and consultants have always worked for several employers. Second sources of revenue have also become very widespread: high school math teachers tutor students at home, students have part-time jobs, and so on.

The function of economics is not to make value judgments about how work is organized; on the contrary, it is important for people to be able to choose the kind of employment that suits them. Some people prefer the relative security of salaried employment and the comfort of being part of an organization managed by someone else. They may also fear the isolation associated with working independently—which helps explain why self-employed people share work spaces, such as “fab labs” (fabrication laboratories) or “makerspaces” for computer sciences and hi-tech entrepreneurs. They do it to share ideas, but also to preserve human contact. Other people prefer the freedom associated with working for themselves. To each according to their tastes.

The amount of self-employment is increasing, along with the fragmentation of labor into microjobs. Many platforms allow someone—perhaps an employee or a retiree—to work a few hours a day to earn a bit of income. Amazon Flex allows people to deliver packages, perhaps in the course of a trip they were planning to make. The idea is that private individuals replace delivery companies for short journeys. Through the Mechanical Turk platform, which Amazon launched in 2005, people can perform small tasks in return for small payments. Some people make a full-time job out of this, while others work only occasionally. Today, there are supposed to be five hundred thousand of these “Turkers” throughout the world. On TaskRabbit, a platform for handyman services, we can hire people to mow our lawns, construct our websites, do house repairs, or help when we move.

There is nothing conceptually novel about all this, but digitization makes it easier to break production up into simple tasks and to connect users. As Robert Reich, President Clinton’s secretary of labor and a critic of this development (which he has called the “share-the-scraps economy”), points out: “New software technologies are allowing almost any job to be divided up into discrete tasks that can be parceled out to workers when they’re needed, with pay determined by demand for that particular job at that particular moment.”17 Supporters retort that it improves the efficiency of a market by matching demand with supply, an exchange in which everyone is a winner. Wealthy households can afford to pay for numerous services that did not exist earlier, or were more expensive. But so can the middle classes, as experience with ride hailing companies shows. In cities such as Paris and London, taxi rides are expensive and relatively few people use them—the welloff and those with expense accounts.18 Many people who hardly ever used this form of transportation have begun to do so since lower-cost services like Uber or Lyft appeared.

What Should We Think about Uber?

The very mention of Uber triggers fierce debates.19 This is just as true in France (where UberPop, with its nonprofessional drivers, was banned in 2015 after protests by taxi drivers) as in the US (where some cities have introduced restrictions) and the UK (where London’s famous black-cab drivers have staged protests and lobbied for restrictions). How should an economist respond? I will limit myself to a few reflections.

1. First, whether for or against Uber (I will return to arguments pro and con), it has certainly brought a technological advance. This advance is simple enough, which shows how harmful an absence of competition (true of many taxi markets before Uber) can be to innovation. What are the innovations adopted by Uber? Automatic payment by a preregistered card, which enables users to leave the taxi quickly; rating both drivers and customers; not having to call and wait for the despatcher to send a taxi; geolocation, monitoring the taxi’s itinerary before and during the trip and so enabling a reliable estimate of the waiting time and journey time; and finally, and perhaps counterintuitively, surge pricing that raises fares when vehicles are scarce. These are almost trivial “innovations,” but no taxi company had thought of them or bothered to implement them.

The most controversial of these innovations is surge pricing; and although one can imagine abuses (in theory the algorithm could raise prices dramatically when a storm is forecast, although in practice Uber refrains from such price gouging by capping fares in emergencies), having pricing respond to supply and demand is, overall, a good thing. The pioneer of peak load pricing was EDF, France’s state-owned energy company, which has long used a pricing scheme thought up by a young engineer called Marcel Boiteux, who went on to become the company’s CEO. Today, this idea is applied under the variant of “yield management” to plane and train tickets, hotel rooms, and ski resorts. It makes it possible to fill rooms or unoccupied seats by charging low prices at off-peak periods without compromising the company’s finances. To return to taxis: when there is a shortage, instead of making users wait endlessly for a car, surge pricing encourages those who can walk, take the subway, or hitch a ride with friends to do that instead. This leaves the rides available for those who have no alternative.

2. Existing businesses may resist new technological developments, but the defense of established interests is not a good guide for public policy. In this case, the status quo is unsatisfactory. In many cities, taxis were expensive and often unavailable. The limited market meant many potential jobs were not created—jobs that could have been done by the people who needed the work most. It is interesting to note that in France, Uber created jobs for young people from immigrant backgrounds in a country where labor market institutions have not worked well for this group.

3. There are two arguments that support the case of traditional taxi drivers. The first is that competition should be on an equal footing; this is a crucial argument. We should calculate whether a traditional taxi and an Uber taxi pay the same social security charges and taxes. Examining these figures would ensure that there was no distortion of competition. This debate is purely factual, and could be conducted objectively—something that was not done in the dispute in 2015 that resulted in the banning of UberPop in France.

The second argument results from a blunder many taxi regulators have made in the past. They granted individuals, free of charge, taxi licenses that were very valuable because they were issued in limited numbers. In theory, these official authorizations cannot be passed on, but in practice they are often resold. The state is responsible for the current fraught situation. Some independent taxi drivers have paid high prices for their licenses, and the new competition is destroying their future retirement savings. This raises the issue of whether the state should compensate them for their capital loss (whereas if there had been no reselling of licenses, the problem would not have arisen, because a right to make income acquired free of charge could legitimately be revoked). In Dublin, the authorities found a clever solution, giving a new license to everybody who already had one as the means of compensation, while doubling the number of taxis. That was the right policy, until the technological progress brought about by ride-hailing platforms.

THE CHALLENGE OF INNOVATION

Employment needs businesses. France has a disturbing shortage of new enterprises at a global scale. All the companies on the Paris CAC 40 stock index—which are often very successful internationally—are descended from old companies. That is not the case in the United States, where just a small proportion of the one hundred biggest listed firms existed fifty years ago. To create jobs, France (and other countries) need to develop an entrepreneurial culture and environment. Globally successful universities are also needed to take advantage of this turning point in economic history, a point at which knowledge, data processing, and creativity are going to be at the heart of creating value. In fact, universities are a sort of condensed version of all the ways businesses will need to transform: more horizontal cooperation and multitasking, an emphasis on creativity, and a desire to realize oneself through work. For its part, the working culture in Silicon Valley or in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has been inspired by American universities, the world their young creators know best.

THE END OF SALARIED EMPLOYMENT?

Is “contingent work,” such as self-employment or gig work, and the disappearance of salaried employment, likely to become the norm, as many people predict? I don’t think so. I would bet instead on a gradual move toward people working independently, not on the complete disappearance of salaried jobs.

This gradual change will happen in part because new technologies are making it easier to put independent workers in contact with customers and to run a back office. Even more important, independent contractors need to create and be able to promote their individual reputations at low cost. Customers used to rely on a taxi company’s reputation, or choose a washing machine by the manufacturer’s brand, rather than rely on the reputation of the employee who happened to drive the taxi or make the machine. Now, as soon as an Uber customer is matched with an available driver, the driver’s reputation is available at once, and the customer can reject the transaction. A firm’s collective reputation, with the concomitant control of its employees’ behavior, is becoming gradually less important than individual reputations.20 This individual reputation, as well as digital traceability of the service provided, is one answer to the question of trust raised at the beginning of this chapter.

But technology can sometimes have the opposite effect and favor standard salaried employment. George Baker and Thomas Hubbard21 give the following example: In the United States, many truck drivers work for themselves, which causes some problems. The driver owns his own truck, which is a substantial investment. Drivers are investing their savings in the same sector as their labor, which is risky—in a recession, income from work and the resale value of the vehicle decrease at the same time. Common sense suggests that people’s savings should not be invested in the same sector as their employment. In addition, owner-drivers have to pay for repairs, during which time their only source of income is unavailable.

In that case, why aren’t truck drivers employees of a company that buys and maintains a fleet of trucks? Sometimes they are, but moral hazard limits this: an employer needs to worry about the driver not being careful with the vehicle, whereas the independent trucker has every incentive to take good care of it. Computerization can alleviate this problem. The trucking company can monitor the driver’s behavior using onboard computers.

More generally, several factors explain why conventional jobs still exist. First, the investment required to set up a business may be too large for a single worker, or even a group of workers. Even if the investments are affordable, some people prefer not to put up with the risk and stress of running a business, such as doctors or dentists who choose to be employees of a medical clinic rather than set up on their own.

Second, from the perspective of a business owner, having someone work for other people may be undesirable for several reasons. If the worker has access to manufacturing secrets or other confidential information at work, an employer is likely to insist that people work for the one firm exclusively. When the work involves teams, and the productivity of each individual worker cannot be measured objectively (unlike that of a craftsman who works alone), the worker is not always free to organize work as he or she likes. In this case, having several employers could generate significant conflicts over the allocation and pace of work. Third, it may be the case that individual reputations based on ratings do not function well. As Diane Coyle notes,22 the quality of the individual consultants may be hard to monitor, at least immediately, by the clients; whereas a traditional consultancy employing individual consultants may be more efficient at “guaranteeing” quality.

In short, I believe that salaried employment will not disappear; but there are good reasons for thinking that it will continue to become less important over time.

A LABOR LAW ILL-SUITED TO A NEW CONTEXT

France, like many other countries, conceived its current labor law with the factory employee in mind.23 It consequently gives little attention to fixed-term labor contracts, and still less to the teleworker, the independent worker, or the freelancer. Labor laws were not written for students or retirees working part time, freelancers, or Uber drivers. In France, 58 percent of employees outside the public sector still have permanent employee contracts, but this proportion is falling. In many countries, such as the UK and US, the number of salaried employees is declining, whereas the number of self-employed workers is increasing. We need to move from a culture focused on monitoring the worker’s presence to a culture focused on the results. This is already the case for many employees, especially professionals, whose presence is becoming a secondary consideration—and whose effort is in any case hard to monitor.

Confronted by these trends, legislators often try to fit new forms of employment into existing boxes, and to raise questions in similar terms: Is an Uber driver an employee or not?

Some people would answer yes, arguing that an individual driver is not free to negotiate prices, and is subject to various requirements for training, type of vehicle, or cleanliness. For some drivers, all their income comes from their Uber activity (others may drive for other ride-hailing platforms, or may have other entirely different jobs, for example, in a restaurant). Finally, drivers with poor ratings may be terminated by Uber.

Yet restrictions of various kinds also do apply to many self-employed workers, who are limited in their freedom of choice by the need to protect a collective reputation—such as that of a profession, a brand, or a wine region’s appellation. In many countries, an independent physician cannot choose the price he or she charges, and must follow specific rules or risk losing accreditation. Even an independent winemaker must respect certification rules.

Others would argue that Uber drivers are free to decide how much they work and where, when they work, and where they go. In addition, they bear the economic risks. So the status of an Uber driver (or others working for similar platforms) is a gray area. They have characteristics of both independent contractors and salaried workers.

In my view, this debate goes nowhere. Any classification will be arbitrary, and will no doubt be interpreted either positively or negatively depending on one’s personal prejudices about these new forms of work. The debate also loses sight of why we classify work in the first place. We are so used to the current framework that we have forgotten its initial purpose, which was to ensure the worker’s well-being. The important thing is to ensure competitive neutrality between different organizational forms: the dice must not be loaded in favor of either salaried employment or self-employment. The state must be the guarantor of a level playing field between organizational forms and not choose policies that make the digital platforms unviable just because they are unfamiliar and disruptive. If there is something wrong with the labor market, policy intervention should fix it, and not cherry-pick a specific organizational form.24

One thing is certain: we will need to rethink our labor laws and the whole work environment (training, retirement, unemployment insurance) in a world of rapid technological and organizational change.

INEQUALITY

Digitization may also exacerbate inequality. First, inequality between individuals. The share of income going to the highest-paid 1 percent of the population in the United States rose from 9 percent in 1978 to 22 percent in 2012.25 As Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee have noted, the big winners of the digital age are “the stars and superstars.”26 In the last forty years, labor economists have analyzed the path of earnings, especially in the United States. The earnings of people with graduate degrees have shot up, while the earnings of college graduates have also risen significantly, although not as much. The earnings of all other groups of workers have stagnated or even decreased.

This polarization is likely to get worse. Innovative, highly skilled jobs will continue to get the lion’s share of income in the modern economy. The problem of distribution will become more difficult; governments will need to ensure a certain level of income for all individuals, and to that purpose will need to choose between regulations that keep wages at a level above the market rate (and thereby cause unemployment) and direct payments (also called universal income or negative income tax). Are we moving toward a society in which a nonnegligible proportion of the workforce will be unemployed, and will have to be paid an income financed by a “digital dividend”? (Compare this to the “oil bonus” that each resident of Alaska automatically receives from the state.)27 Or are we creating a society in which this part of the population will hold low-productivity public service jobs (as happens today in countries like Saudi Arabia)? These solutions however may contravene individuals’ desire to gain dignity through work, and will also require countries to be able to access the digital manna.

There indeed may also be substantial inequality between countries. Let us sketch out an extreme scenario to illustrate the danger of this trend. In the future, countries that can attract the most productive people in the digital economy will disrupt the value chain in every sector and appropriate immense wealth, while the other countries will have only the scraps. This inequality could result from differences in public policy concerning higher education and research, and from innovation policy more generally. But it will also result from fiscal competition. The mobility of talented people—a labor market that is now completely globalized—will lead many of these wealth creators to migrate to countries that offer the best conditions, including the lowest tax. This also relates to the inequality of individual incomes. Countries not taking part in this global competition for talent will not be able to redistribute wealth to the poor, because the poor will be all that they have. While this scenario is too simplistic (and exaggerated for effect), it illustrates the problem. Unlike oil manna, digital manna is mobile.

THE DIGITAL ECONOMY AND EMPLOYMENT

THE JOBS MOST IN DANGER

Not a day passes without an article appearing in the press, fretting about the mass unemployment that will be created by the digitization of the economy. One example is the furor over a statement in 2014 by Terry Gou, the CEO of Foxconn, a Taiwanese electronics company with 1.2 million employees located mainly in Shenzhen and elsewhere in the People’s Republic of China. Gou said that his company would soon use robots in place of humans, in particular to assemble new iPhones.

Machine learning and AI will also change the employment structure. To some extent, this will just accelerate an ongoing trend. Many jobs involving routine (and thus codifiable) tasks, such as the classification of information, have been eliminated: banking transactions are digitized, checks are processed by optical readers, and call centers use software to shorten the length of conversations between customer and employee, or even replace humans with bots. Book and record stores have disappeared in many cities.

These changes are concerning. Most emerging and underdeveloped countries have counted on low salaries to attract outsourced jobs from developed economies, using this route to escape poverty. Robots, AI, and other digital innovations substituting capital for labor threaten their growth. And what about developed countries? If even Chinese labor is becoming too expensive, and will be replaced by machines, what will happen to better paid jobs in these countries?

David Autor, a professor of economics at MIT, and his coauthors have studied the polarization over the last thirty years resulting from technological change in the United States, Europe, and other countries.28 Digital technologies tend to benefit those employees, generally highly trained, whose skills complement the new digital tools; obviously, it also means fewer jobs for those whose work can be automated, and “hollows out” the distribution of jobs into either high-paying skilled positions or low-paying basic service positions. The kind of jobs being found more often are, at the bottom of the salary scale, those for nurses, cleaners, restaurant workers, custodians, guards, and social workers, for example, and, at the top of the salary scale, for business executives, technicians, managers, and professionals. Jobs offering middle-level salaries—for administrative personnel, skilled laborers, craftsmen, repairmen, and so on—are now relatively less available. In the United States, the difference in salary between those who hold university degrees and those who left right after high school has grown enormously in the past thirty years.

Computers can easily replace humans for certain tasks. Deductive problems require applying rules to facts: the particular is deduced from the general rule in a logical way. An ATM verifies a card number, the PIN code, and the bank account balance before issuing money and debiting the account; programing these operations replaced many of the earlier functions of bank tellers. Nonetheless, total employment in banking rose even as the ATM network spread, because demand grew and teller jobs were replaced by new tasks.29

On the other hand, induction, which starts with specific facts and works toward a general law, is more complex. There has to be enough data for the computer to discover a recurrent pattern. But great advances have been made on this front. For example, algorithms could predict the United States Supreme Court’s decisions about patents as well as any legal experts. Similar techniques are enabling automated facial recognition, voice recognition, medical diagnosis, and other tasks that previously only humans could perform.

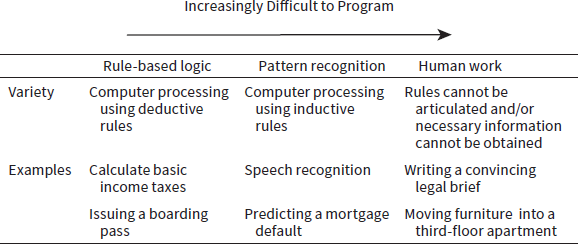

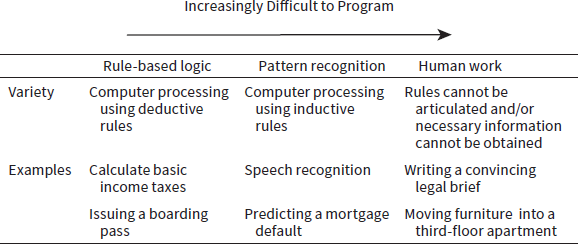

The hardest tasks for a computer arise with unforeseen problems that do not match any programmed routine. Rare events cannot be analyzed inductively to generate an empirical law. Frank Levy (MIT) and Richard Murnane (Harvard), one of whose diagrams I reproduce in table 15.1, give the following example: Suppose a driverless car sees a little ball pass in front of it. This ball poses no danger to the car, which therefore has no reason to slam on the brakes. A human being, on the other hand, will probably foresee that the ball may be followed by a young child, and will therefore have a different reaction. The driverless car will not have enough experience to react appropriately. This does not mean, obviously, that the problem cannot be solved eventually, because the machine can be taught this correlation. But this example illustrates the difficulties still encountered by computers.

Table 15.1. The Disappearance of Jobs

Source: Frank Levy and Richard Murnane, Dancing with Robots, NEXT report 2013, Third Way.

The challenges for humans and computers are therefore different. Computers are much faster and more reliable when processing logical and predictable tasks. Thanks to machine learning, computers can increasingly cope with unforeseen situations, provided they have enough data to recognize the structure of the problem. On the other hand, the computer is less flexible than the human brain, and is not always able to solve some problems as well as a five-year-old child. Levy and Murnane conclude that the people who will do well in the new world will be those who have acquired abstract knowledge that helps them adapt to their environment; those who have only simple knowledge preparing them for routine tasks are most in danger of being replaced by computers. This has consequences for the education system. Inequalities due to family background and education are likely to increase further.

THE END OF WORK?

Although the current changes are occurring faster than previous technological advances, what is happening to work nonetheless shares the same characteristics. I have already mentioned the well-known episode at the beginning of the nineteenth century in Britain, when the Luddites (skilled textile workers) revolted by destroying new looms that less-skilled workers could operate. The Luddite revolt was brutally suppressed by the army. Another example of dramatic change is the reduction in demand for agricultural labor in the United States; in less than a century, the proportion of workers employed in agriculture fell from 41 percent to 2 percent of the total. Despite this massive loss of agricultural jobs, unemployment in the United States is only 5 percent. This illustrates the fact that the destruction of some jobs is compensated by the creation of new, different jobs.

Technological progress destroys jobs and creates others, normally not harming employment in aggregate. For digital technology, the most visible jobs created are those connected with computer science and the digital sector. After more than two centuries of technological revolutions, there is still little unemployment.30 The alarmist predictions of the end of work have never been realized. As Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee note,

In 1930, after electrification and the internal combustion engine had taken off, John Maynard Keynes predicted31 that such innovations would lead to an increase in material prosperity but also to widespread “technological unemployment.” At the dawn of the computer era, in 1964, a group of scientists and social theorists sent an open letter to U.S. President Lyndon Johnson warning that cybernation “results in a system of almost unlimited productive capacity, which requires progressively less human labor.”32

To return to the question of inequality, the right question is not whether there will still be work. The real question is whether there will be enough jobs paying decent wages. This is difficult to predict. The recent developments suggest not. On the other hand, most individuals want to be useful to society—work, remunerated or not, is one way to do so. As Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee note, employment is one way we construct the social fabric. Perhaps people will be prepared to accept low pay in return for this social bond. In the shortest term, however, the destruction of jobs is costly for those who lose them. The acceleration of creative destruction raises three questions: How can workers, with jobs or not, be protected? How can we prepare ourselves for this new world through education? How are our societies going to adapt? Burying our heads in the sand is not a strategy.

THE TAX SYSTEM

Finally, the digitization of the world of work confronts us with new fiscal challenges and exacerbates existing ones, both within countries and internationally. I will just mention them here.

NATIONAL ASPECTS

One issue at the national level is the old one concerning the distinction between commercial transactions and barter. The demarcation between the two is subtle, but they are treated in radically different ways for tax purposes. If I employ a construction company to paint my home, my payment is subject to value-added tax, and the employee and the employer are taxed depending on their status (social security charges, income taxes, corporate taxes, and so on). If I ask a friend to do the job, and give him a case of good wine in return, no taxes or social security contributions are levied. This is not only because the tax office would find it hard to spot this transaction, but also because it is a noncommercial exchange, and so not liable for tax. But where does the noncommercial stop and the commercial begin? Trade with one’s family and friends, or exchange in clubs or small-scale cooperatives, meets most criteria for a producer-consumer relationship. So is it really noncommercial? Why does this classification mean the transactions are treated differently for tax purposes? These questions are particularly important in a country like France, where labor is heavily taxed (60 percent on average for the social security contribution, 20 percent for the VAT, and an income tax that can be high if one does not benefit from the many loopholes). The questions are fundamental for the sharing economy: Is my membership in a car club “sharing” a simple commercial relationship? As with labor law, we owe it to ourselves not to simply try to put the new economy’s activities in preexisting but arbitrary boxes; we need to rethink our tax system.

INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS

International taxation also poses many challenges. Practices such as the use of transfer pricing between the divisions of a multinational company to locate profits in a country with low corporate taxes are now pervasive. A company might make a subsidiary in a country that has a high corporate tax pay a gold-plated price for services or products provided by a subsidiary in a country with a low corporate tax. It does this to empty the high-tax subsidiary of taxable profit. This fiscal arbitrage, designed to reduce corporate tax liability, has always existed. Such practices are inevitable when there are no international accords on tax harmonization. Multinational companies like Starbucks and Amazon are thus regularly criticized in Europe for their intensive fiscal “optimization.”

The fact that digital business is dematerialized makes this arbitrage even easier. We no longer know exactly where an activity is located. It is easier than it used to be to place profitable entities in countries with low corporate taxes, and vice versa, and to shift profits using transfer prices. Intellectual property rights to a book or a design or software can be established in any country, independent of where they are consumed. Advertising fees can be collected in Ireland, even if the target audience is in France. Large US corporations use a complicated structure based on a technique known as the “double Irish,” which grants intellectual property rights to an Irish corporation located in Bermuda (in Ireland, there are no taxes on the profits of offshore branches, and thus on the profits of branches located in Bermuda).33 The United States Treasury does not profit from this either, because overseas profits of US companies are taxable in the US only when they are repatriated. Therefore, the money is left in Bermuda and only ever repatriated when there is a tax amnesty in the United States. It is estimated that the five hundred largest American firms have two trillion dollars parked abroad.

The Internet has no borders, which is good. But countries need to cooperate on taxes34 to prevent tax competition for overseas investors (the question of the “correct” level of taxes on corporations is different; I will not take that up here).

An example of an agreement to end tax competition is the 2015 agreement on the value-added tax on online purchases within the European Union. This authorizes the purchaser’s country to add value-added tax to the online purchase; previously the value-added tax was levied on the supplier, encouraging companies to locate in countries with low value-added tax rates, and to sell to consumers located in countries with high value-added tax rates. The new system is a satisfactory regulatory response for business models such as Amazon’s, which bill the individual consumer. But it does not resolve the problem of platforms like Google, which technically does not sell anything to the French consumer, but charges advertisers who do. Regulators are discussing this problem, because the tax base in this case is much less clear than in the case of a sale of a book or a piece of music.

Digitization represents a marvelous opportunity for our society, but it introduces new dangers and amplifies others. Trust, ownership of data, solidarity, the diffusion of technological progress, employment, taxation: these are all challenges for the economics of the common good.