If you tell people where to go, but not how to get there, you’ll be amazed at the results.

George S. Patton

In 1948, ten years after Jonathan’s arrival, my parents began talking about having another child. They both loved children and thought it would be nice for Jonathan to have a younger brother or sister who could support him after his two older brothers left home, or after they themselves were gone. If they had another baby, there would always be someone to look after Jonathan. They felt no fear, only anticipation, at the prospect of another child. A doctor said there was virtually no chance that they would have another deaf baby. My parents were convinced that the next child would be hearing and healthy.

My father wanted a girl this time. He would name the baby Dorothy Louise after my mother. She, however, wanted another boy, since she was more confident about raising boys.

I arrived at King’s Daughters Hospital on February 15, 1949, very much a male—and also, as my mother suspected immediately, with no more ability to hear than Jonathan. Either the hair cells of the cochlea in my inner ears or the auditory nerve that transmits signals from my inner ears to the auditory cortex of my brain were damaged (I’ve never learned which). I was born profoundly deaf.

My mother waited six weeks to tell my father. He was again beset by a reality he wasn’t prepared for. He tried to fit this new family “tragedy” into some logical place in his world. But it wasn’t easy for him, the great believer in order and harmony. It wasn’t easy at all.

For one thing, there was no such thing as genetic counseling in those days. My father mused and worried about how strange it was for our family to have two deaf children. There was no one he could turn to for a logical explanation. He knew there was no deafness in his family or my mother’s. Uncles on both sides of the family were genealogy experts and they could find no record of deafness going back three hundred years.

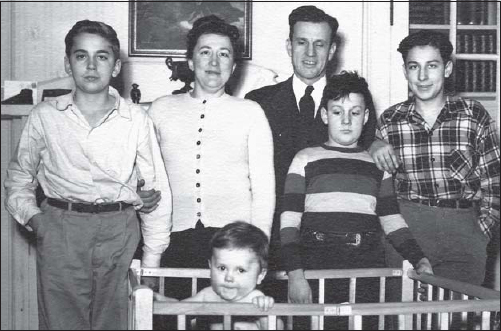

First family photo. Ten-month-old Paul with his family (L to R: thirteen-year-old David, Mother, Father, eleven-year-old Jonathan, fourteen-year-old Dunbar).

Satisfied that there was no evidence of inherited deafness, my father decided that Jonathan and I were products of our mother’s thyroid condition. She had suffered from an overactive thyroid while pregnant with Jonathan and had almost miscarried him. Several years after he was born, she had an operation to remove part of the gland to eliminate an overactive rate of metabolism.

My mother started my education right away. With Jonathan, my parents had to gather and sift through all the information they could find about deafness before they could proceed with home instruction. With me, all they had to do was bring down from the attic the boxes of instructional materials they’d collected for my brother. Their experience with Jonathan saved me years of frustrating interaction with my family and professionals.

From Jonathan, my family learned that deafness affects hearing and speech but not the impulse to communicate. They knew that I also would have a great desire and need to communicate with others. After all, as humans, our satisfaction and success in life has everything to do with our ability to send and receive messages and interact with others. We all long to be understood—by our friends, our bosses, our parents, our children, and most certainly by our boyfriend, girlfriend, husband, or wife. Nothing is more frustrating than trying to express a vital message or our innermost thoughts and realizing that our coworker, teenager, or lover isn’t getting it—or worse, that he or she isn’t even trying to understand!

When communication succeeds between us and another person, however, it unlocks the potential of the relationship. We discover points of common delight. Ideas pour out and build on each other. A bond forms. Even when we disagree, communication creates a connection that often leads to mutual trust and respect. An effective exchange allows us to see circumstances from another’s perspective. And when communication flows at an intimate level, it can open the door to love.

Jonathan introduced my family to the idea that communication can take place without hearing and speech. My parents and brothers had learned that hands and arms, faces, postures, gestures, and expressions are as important to communication as lips, tongues, and vocal cords. We have our eyes, which read those gestures and postures, the thousand avenues of facial and body expression. And we have our lips to form unspoken words.

However highly my family valued words, they knew that some people overvalued speech as a means of transmitting information. My family didn’t think of speech as the only means of communication. Their experience and intuition taught them that a large percentage of social conversation among hearing people is nonverbal in nature and that only a small portion of the total energy used in communicating is expended in the utterance of words. They also learned that everyone transmits and reads body language, for the most part unconsciously. Jonathan’s deafness made my family aware of their bodies as well as their speech. They learned to sharpen their perceptions about gestures, postures, and facial expressions and to loosen up and use these elements when communicating with Jonathan. By the time I came along, my family, especially my mother and brothers, were experts at nonverbal communication.

In my early years, as with any young child, much of what I needed to get across to my family and others involved primarily my feelings. These messages came through in body language, and my family responded to me immediately. All families respond to their babies’ expressive motions, but they usually treat such movements as basically informative only. The baby smiles: it is content. The baby cries: it is wet or hungry. Their babies’ expressions and gestures give them pleasure, but it is not until the children learn to talk that many parents think of them as communicating beings.

My family had a special reason to concentrate on my vocabulary of body movements, gestures, and sounds. By learning to read my body language and noises, they came a step closer to participating in an ongoing conversation with me that was as valid and informative as any spoken exchange. Eventually, we developed a system of signs and signals that seemed to be born out of our subconscious.

My family wanted me to learn to speak, but they intuitively supported all my communication efforts. Their positive attitude about nonverbal methods enhanced our overall communication. With my family’s support, not pressure, I picked up words and started communicating very quickly.

It helped that my family was naturally physical. My mother held and hugged me often. My brothers and father wrestled with each other and me because my father was strong and had been a wrestler in college. From the very beginning, my brothers added me to their horseplay. We played physical games and boxed each other around—activities that sometimes led to fights among the older boys, though they were surprisingly careful with me.

It was a graphic way to communicate. It showed me how much they loved me and that they treasured me as part of the family. I remember especially my father playing “airplane.” He lay on his back on the floor with his feet straight up in the air, and one of us—the “airplane”—balanced on our stomach on the soles of his feet. I also remember him flipping us. As he lay on his back supporting me by the shoulders with his hands, my hands would be on his knees while he kept my body straight up in the air. Then he would flip me over so that I would land back on my feet. We did many other daring acrobatics, and my mother would watch with fear and trepidation.

My father played these physical games with me until I was about twelve. It seemed to make up for all the time he didn’t spend communicating with me. My father was out of the house most of the time, and because of his impatient nature he had more difficulty than the rest of the family in understanding my sounds, gestures, and beginning words. The older I got, however, the easier it was for him to understand me.

My mother worked with me on jigsaw puzzles. She started with simple ones and went on to larger and more complicated puzzles. This was an important mental exercise in spatial relations. During our time with these puzzles I imitated and lipread my mother, and as I did so I learned to use my voice. I formed many words on my lips and eventually burst out with my own voice. To begin with, my father and brothers often had trouble understanding my speech. But as time passed they could usually decipher the words by watching my face. Therefore, while I was learning to lipread them, my family was learning to lipread me as well.

It was a matter of trial and error. In a way, it was like all the other games we played. We boys touched and pummeled each other and made up physical tricks almost constantly. It was contact, it was recognition, it was love—and it was a form of communication.

Verbal language is also physical. My family learned to listen to me by watching me and figuring out what I was saying. This meant a lot of lipreading and it became very accurate. Since I imitated what I saw on the lips of others but not the inner mechanics of sounds when I spoke, it took more work on the listener’s part. I used an exaggerated way of saying things with the lips, tongue, and teeth. But an average listener couldn’t understand my words since I was imitating visual cues, not sounds. In fact, no one outside my family could understand me, so my family interpreted for me. It was amazing how my family lived with so many of my mispronunciations. But they were unconcerned at the time with fine-tuning my speech. My parents’ major objective had been achieved—to get me to use my voice to communicate. It was a goal they had set with certainty, based on their early years with Jonathan, eleven years before.

Almost anyone, even the uninitiated, can understand the mouthing of words and the sounds I make now. The crucial point is whether they’re interested in hearing me or not. Some people are embarrassed by the process. Others, it seems, don’t want to be bothered. This is a pity, because just as they might learn something about the rest of the world by speaking with a foreigner, they would also learn from “talking” with a deaf person.

When Jonathan was very young, as with me later, my parents explained to Dunbar and David that excessive use of sign language would cut Jonathan off from most hearing people. They told the boys that when they felt like using a homemade sign for a word Jonathan already knew, such as “snipping” two fingers together to indicate scissors, they should put their hands behind their back. That was the rule while talking to Jonathan: if he had already learned to lipread a word, then they would not substitute a sign if he failed to lipread it. Instead, they should repeat the word. If that failed, they should stop and work on it with him again, or find another word (though they often used the gesture eventually).

This process required looking Jonathan squarely in the face and enunciating clearly and slowly, “Do you want a bath?” rather than just pointing to him and then pointing to the bathtub. It caused the whole family to slow down and think about how they communicated. In some ways, I believe they profited from it as much as Jonathan and I did.

My older brothers communicated with us in other ways, which often included a barrage of visual pranks and body language. They used pantomime to act out stories, events, and jokes. One favorite game began with Dunbar or David pointing excitedly off to the side. Jonathan or I would look, and then one of the brothers would bop us on the right shoulder. Or, while we were turning around, one of the two would make our piece of cake disappear, then start looking under the table for the cake! We received more than our share of this kind of teasing, but I at least usually liked the attention.

It would have been much easier, of course, for Jonathan and me had the rest of the family signed for words like “scissors.” But my parents and brothers encouraged us to practice lipreading so that we would become better at it. My family certainly never resorted to punishing Jonathan or me for using some signs, as some families did. Instead, they always tried positive encouragement as a way of getting us to talk and lipread more.

My parents’ decision to discourage sign language within our household reflects one side of the philosophical coin in deaf education. Many educators favor teaching sign language to deaf children. Others prefer oralism, while still others teach and practice both methods. The foundation of my parents’ approach was a fierce commitment to communication and family unity. They did not know that a vibrant deaf community used sign language, and they continued to trust the prevailing view of professionals regarding signing. Even so, they could not bring themselves to discourage my brothers from using the gestures and facial expressions that helped Jonathan and me stay within the web of communication that bound our family together.

In doing so, my parents unknowingly expressed a belief that I have grown to feel strongly about—parents and teachers should use whatever works, be it physical contact, speech, lipreading, signing, or a combination of each. Deaf people need to communicate, no matter the means.