The Greeks are camped on the edge of the beach, a gang of men divided among themselves, with no secure leadership, the atmosphere angry and uncertain, no constancy in their arguments or their dealings with each other, no faith in their purpose, no substance in their loyalties and no women with any significance beyond their sex. They are living in rough sheds built against their ships. The rigging has rotted. They are surrounded by loot but sleep on the skins of wild animals. Dogs eat the dead. Dogs are everywhere on the battlefield. They chew at the genitals of the corpses, and birds clap their wings over the remains. If you walk across that realm of death at night, you must pick your way through “the abandoned weapons and the black blood.” The Greeks confront the realities of life and death with unadorned directness. No family, no safety, no home, no sense that virtue is rewarded or frailty sheltered. No prospect of dignity in old age or security when weak. No meaning beyond the presence of force.

They have been here too long, and the language vibrates with its own violence. The burningly angry killer-chief Achilles says that Agamemnon, his nominal leader, is dog-eyed, dog-faced, shameless, greedy, a wine drinker, with his heart as flaky as a deer’s. Agamemnon calls Achilles “the most savage man alive, violence itself, beyond all feeling.” Anger and disgust ripple through their “shaggy breasts,” in the roughness of their hearts. In private they are tender about themselves and their girls, but here they overbrim with hate, each longing for the other’s “black blood to come pumping out on to my blade.” They stand nostril to nostril in mutual loathing. This is a gang world, marginal, desperate and tragic, a place of outsiders. Civilization it is not. Like all gangs, they have their meetings and their discussions, their insistence on hierarchy and obedience. And this fight between the leaders feels ugly and unwelcome, deplored by the old men. Nevertheless, it is an organic part of who the Greeks are, one aspect of the anarchy and violence that crouches just beneath the surface of every interaction between them. The Greeks are the barbarians in this story.

Across the plain, Troy is different. Here are the people of a city, full of conviction, with well-ordered relations, allies who remain true to each other, a king to whom all give respect, brothers, sisters, wives, parents and children all living in a mutually dependent, interlocked system, with institutions that seem permanent. Noble women lead graceful lives. There are arguments within the family, there are hints of luxury and softness, but this is a place where not merely the bodies of slaughtered animals but woven and embroidered cloth, the flexible and intricately constructed thing, is the offering they make to the gods.

The Trojans are at home, and the web of their connections is wound closely around them. When Hector, their young war leader, midbattle, returns to the gates of the city, “the wives and daughters of Troy come crowding up around him, asking for their sons, brothers, friends and husbands.” (This is the network the Trojans are embedded in.) Hector goes into the city, to the palace of Priam, his father, and enters

that most beautiful house

Built with polished colonnades—and deep within its walls

are fifty chambers of polished stone, built close to one another;

in them the sons of Priam sleep beside their wedded wives;

and for his daughters on the other side, inside the court,

are twelve roofed chambers of polished stone, built close to one another;

in them the old king’s sons-in-law sleep beside their respected wives.

It is the geometry of coherence—of repetition and continuity—of people understanding and responding to the virtues of mutual accommodation, the opposite of the shiftless place of the Greeks outside. So this is the confrontation: gang against city, individual violence against domestic order.

The wind blows unbroken across the plain, and among the Greeks unbridled maleness meets in erect competition or tensed standoff. The sexuality is inescapable. It takes the old Greek war-leader Nestor to say it. When persuading doubters not to return to Greece before Troy falls, he gives them the plain invitation: “Let no man hurry to sail for home, not yet … Not until he has slept with the wife of some Trojan.” Only sex with the enslaved wife of a dead enemy could justify the grief and trouble they have endured over Helen. The symbols at the heart of the city of Troy are those elegant, well-swept corridors of polished stone and the beautiful woven cloth its people give their gods; for the Greek camp it is edge-sharpened bronze and the unsheathed phallus.

The Iliad is not shut into the Trojan plain; it loves mobility; its gods and goddesses fly across the islanded world of the Aegean with effortless fluency and a wide surveying sense of its geography. The poem often travels away to Olympus, the home of the gods, to Africa and to other mountains where the gods take up temporary residence. Minor deities are sometimes caught between flights, rushed off their feet, in transit from Anatolia to Egypt, or to a dinner party in the house of the west wind. But the poem never goes to Greece. No scene is set in a Greek house. Greek places are referred to with formulaic adjectives—“rocky,” “with-many-ridges,” “sheepy”—but with none of the overwhelming sense of reality that clusters around Troy and its rivers, its woods, springs, washing places and even individual trees and burial mounds. In that poetic sense, at one of the deepest levels of the poem, the Iliad portrays the Greeks as a long way from home.

It is true that they occasionally refer to the places they come from, but the psychological weight in those references is not to buildings or cities. The Greeks look back with longing and a sense of loss to their families, their distant fathers and their fathers’ fathers, their wives and children, the brotherhood of their clans, the hearths which are defined by the people who gather around them, not to any palaces. They love their land, which gives them food and sustenance, its wheat-bearing fields and lovely orchards, but not the kind of deeply instituted fixity and built wealth they have come to get their hands on at Troy. What they miss, in a phrase that is repeated again and again, is “the loved earth of their fathers.” But in Greek there is no distinction between “fatherhood” and “fatherland.” The word for them both is patra, and it can apply in Homer to a shared descent, a cousinage, a sense of family or clan. Fatherhood is fatherland, and blood and heart are home.

Even the loved earth of the fathers is trumped by something else in the Greek mind. When the great owl-eyed goddess Athene, terrifying in her power, carrying her magic aegis, or breastplate, moves through the Greek army, putting a deep hunger for violence in their hearts, allowing them to fight without rest, home itself drops into insignificance.

And now sweeter to them than any return

In their hollow ships to the loved earth of their fathers

Was battle.

The word Homer uses for the deliciousness of that violence in battle is glukus, “sugary,” even “sickly,” used of nectar and sweet wine, of the people you love. Battle, in many ways, is the Greek home. As the agents of severance, they are themselves severed from home. The most delicious thing they can imagine is a world of unrelenting violence.

* * *

“Beware the toils of war,” Sarpedon the Lycian hero says to Hector, “the mesh of the huge dragnet sweeping up the world.” Buried inside that terrifying image of war trawling for the lives of men, its net stretched from one horizon to the other, ushering the mortals into the cod end, is the Greek word for flax, the thread that the Fates use at the beginning of each of our lives to spin our destinies. And so the metaphor makes an assumption: war is part of destiny. It is not an aberration or a strangeness. It is, for Homer, a theater in which the structure of reality is revealed.

Simone Weil and many others have read the Iliad as an antiwar poem. But to see it as a polemic in that sense is to reduce it. Homer knows about the reality of suffering but never thinks of a world without conflict. On the shield of Achilles, the smith god Hephaestus creates dazzlingly opposed images of the good world and the bad, set against each other. But even in the good world of justice there is still murder and violence. We might long for peace, but we live in war, and the Iliad is a poem about the inescapability of it.

All of that lies behind the Iliad’s massive oversupply of suffering. The poet’s conception that the Greeks have been on this beach for nine long, dreadful years—a historical absurdity—stands in for eternity. This is how things are. This is how things have always been. This is how things are going to continue to be. War is the air a warrior society must breathe. And alongside that everlastingness of grief, its repetitive return, is a deeply absorbed knowledge that suffering can only be told in detail. No counting of casualties will do; no strategic overview will understand the reality; only the intimate engagement with the intimacy of pain and sorrow can ever be good enough for the enlightenment that is Homer’s purpose.

Scholars have worked out that 264 people die in the course of the Iliad. It doesn’t seem enough. One atrocity in some villages on the northern borders of Syria, one nighttime drowning of African refugees in the Mediterranean, one week of car bombs in Baghdad—any of them can outdo it. Only the epic engagement with Atē, the blind goddess of ruin, whose name means both “wrongness” and “wickedness,” can tell what those figures conceal. People are pitiably weak in the face of ruin, pathetically hoping that their prayers for happiness might prevail. That is why the goddesses of prayer in the Homeric universe are broken, tragic figures:

they limp and halt,

they’re all wrinkled, drawn, they squint to the side,

can’t look you in the eye, and always bent on duty,

trudging after Ruin, maddening, blinding Ruin.

But Ruin is strong and swift—She outstrips them all,

loping a march, skipping across the whole wide earth

to bring mankind to grief.

And the Prayers trail after, trying to heal the wounds.

Christians might think of prayer as something that can summon divine power; Homer knows different. “Of all that breathe and crawl across the earth,” Zeus himself says, “There is nothing alive more agonized than man.” The term the great god uses is oïzuroteros, “more miserable,” from the word for a wailing lament, the unbroken, everlasting, ululating cry that echoes from one end of the Iliad to the other.

When the poet is reaching for a comparison that will sharpen the pity of life and the futility of killing, it is fish that repeatedly drift into his consciousness. Perhaps because they are so disgusting, nibbling at the bodies of the dead; perhaps because a fish is so unable to look after itself when caught on a hook, in a net or on a spear, both fish and fishermen are for Homer absurd.

Fish gasping for the sea are not simply poignant in their hopelessness. In the Iliad fishing is the source of some of Homer’s bitterest and jokiest comparisons. When Patroclus, the friend and childhood companion of Achilles, his great intimate in a world where no one else seems to love him, borrows Achilles’s armor at a moment of great crisis for the Greeks in the war at Troy, and strides out into the mass of the Trojans, he pins them against the ships drawn up on the sand. This is his aristeia, his moment of greatness, his time of horror. Patroclus rampages through the Trojan bodies, repetitively and brutally: “Patroclus keeps on sweeping, hacking them down, / making them pay the price for Argives slaughtered.”

One poor Trojan, Cebriones, a bastard son of Priam, the king of Troy, is killed by Patroclus with a stone smashed into the front of his skull. Both Cebriones’s eyes fall out into the dust at his feet, and the body, jerked into death, somehow dives out of the chariot to join them. The beautiful, elegant, much-loved Patroclus mocks the corpse: “Hah! look at you! Agile! How athletic is that, as if you were diving into the sea. You could satisfy an army if you were diving for oysters, plunging overboard even into rough seas as nimbly as that.” Corpse as oyster diver; ridiculous victim, vaunting killer. At one point, in describing Patroclus’s safari, Homer sinks to nothing but a list of the names of those he destroys: “Erymas and Amphoterus and Epaltes and Tlepolemus son of Damastor and Echius and Pyris and Ipheus and Euippus and Polymelus, son of Argeas: corpse on corpse he piles on the all-nourishing earth.”

Patroclus moves on, as Robert Fagles translated Homer’s phrase for the unstoppability of this, “in a blur of kills.” But then the rapidity, the appetite for more, stops and stills for a moment, and dwells on the detail of one particular death, one moment of heroic prowess.

Next he goes for Thestor the son of Enops

cowering, crouched in his beautiful polished chariot,

crazed with fear, and the reins jump from his grip—

Patroclus rising beside him stabs his right jawbone,

ramming the spearhead square between his teeth so hard

he hooks him by that spearhead over the chariot rail,

hoists and drags the Trojan out as an angler perched

on a jutting rock ledge drags some fish from the sea,

some precious catch, with line and glittering bronze hook.

So with the spear Patroclus gaffs him off his car,

his mouth gaping round the glittering point

And flips him down facefirst,

dead as he falls, his life breath blown away.

Man as fish, body as rag doll, killing as a form of acrobatics, the absurdity of the slaughtered corpse—this is vertigo-inducing, a plunge into the black hole of reality, fueled by the mismatch of sea-angling with war.

Christopher Logue, the most brilliant of all modern interpreters of Homer, drove these lines farther into domestic savagery.

Ahead, Patroclus braked a shade, and then and gracefully

As patient men cast fake insects over trout,

He speared the boy, and with his hip as pivot

Prised Thestor out of the chariot’s basket

As easily as lesser men

Detach a sardine from an opened tin.

The first fighting does not begin until 2,380 lines into the Iliad, but thereafter the blood flows, increasingly, with an increasing intensity and savagery, until the climax comes in the crazed berserker frenzy of Achilles’s grief-fueled rampage through the Trojans. The culmination is in the death of Hector, when steppe-man finally meets and kills the man of the city. The Greeks might think battle sweet, their warriors might see battle not as a burden but a cause for rejoicing, but Homer does not.

Now the sun of a new day falls on the ploughlands, rising

Out of the quiet water and the deep stream of the ocean

To climb the sky. The Trojans assemble together. They find

It hard to recognize each individual dead man;

But with water they wash away the blood that is on them

And as they weep warm tears they lift them on to the wagons.

Great Priam does not let them cry out; and in silence

They pile the bodies on the pyre, and when they have burned them

go back to sacred Ilion.

The Greek words translated here by Richmond Lattimore as “hard to recognize” carry multiple meanings. Chalepos (hard) means both “emotionally painful” and “difficult to do”; it is a word that can be applied either to grieving or to rough ground over which you cannot help but stumble as you walk. Diagnonai (to recognize, like diagnosis) means “to distinguish or discern,” to sort out a single important thing from a confused mass, to find individuality amid the blood and muck of the heaped-up bodies. So the phrase can mean either that it was physically difficult in the mounded carnage to make out who it was that was dead; or that finding your own dead amid the mass of others was the most harrowing of experiences. Or both. Those hot, silent Trojan tears, dákrua thermà, allied in these lines with the deep calm of the ocean and the water that washes the blood away, are among Homer’s greatest legacies to us, the persistent belief, amid all this damage, that there is value and beauty in human ties.

* * *

Homer’s portrait of the Greeks at Troy fits the historical situation in the centuries after 2000 BC, when newly empowered northern warriors, equipped with sailing ships and chariots, could batten on the walls of a rich trading city in northwest Anatolia, clamoring to get at its women and its goods. But it is also a portrait of something more enduring: a well-set-up, well-defended establishment is under attack from outsiders who long for, envy and wish to destroy it. The siege at Troy, often seen as a kind of war, as if these were two states battling with each other, is in fact more like a gang from the ghetto confronting the urban rich. Outsiders and insiders, nomadic and settled, the needy and the leisured, the enraged and the offended—the hero complex of the Greek warriors is simply gang mentality writ large.

Iliadic behavior echoes through modern urban America. As the criminologists Bruce Jacobs and Richard Wright documented from the streets of St. Louis, Missouri, American gang members talk about themselves, their lives, their ambitions, their idea of fate, the role of violence and revenge, in ways that are strangely like the Greeks in the Iliad.

Revenge is at the heart of their moral world, a repeated, angry and violent answer to injustice, to being treated in a way that does not respect them as people. There appears to be no overriding authority or legitimacy on the streets of St. Louis. Authority resides in the men themselves and their ability to dominate others. “This desire for payback,” Jacobs and Wright say, “is as human and as inevitable as hunger or thirst.” Crime itself on these streets becomes moral, and revenge a form of justice.

Like the Greeks, these gangsters are “urban nomads,” not set up in their elaborate houses, but living nowhere in particular, “staying” or “resting their head” in different places according to mood or what is going on. They are rootless, dependent on themselves, displaying their glory on their bodies, in their handsomeness, their jewelry and in the sexiness of the women on their arms and in their beds.

They can only rely on themselves: “maintaining a reputation for toughness dominates day-to-day interaction.” And because any act of revenge has to deter the enemy from taking revenge in his turn, there is an accelerator built into the process. Any insult, any slight, any suggestion that you are not a man worthy of respect summons severe, intense and punitive retaliatory violence. Achilles longs to kill Agamemnon after he has humiliated him in public over a slave girl he loves. The St. Louis gangsters take revenge without a thought.

One evening a man called Red knocks into a stranger at a bar by mistake and spills his glass of cognac on him. In response, the stranger “bitch-slaps” him, not with a closed fist but with an open hand, usually reserved for women. “Everyone was watching,” Red says, “so it made me look bad.” Red leaves the bar and waits in the dark in the parking lot. When the man comes out he shoots him, not once but several times. This is the only way in a warrior society that you can be yourself or protect the fragile boundaries of the self, forever under attack from those around you who are all feeling the same.

Homer usually talks with a mysterious decorum about acts of extreme and horrifying violence, perhaps as a product of the poem evolving over generations, so that a kind of linguistic dignity is laid over the top of the violence itself; but have no doubt, the words of the gangsters reflect a Homeric reality, nowhere more than in book 10 of the Iliad. The behavior that book describes is peculiarly horrible, a stripping away of any skin of dignity and nobility. Like “two lions into the black night/Through the carnage and through the corpses, the war gear and the dark blood,” Odysseus and Diomedes slink off toward the Trojan line.

They come across a young Trojan, Dolōn, out in the night and set off to chase him, “like two rip-fanged hounds that have sighted a wild beast, a young deer or a hare.” They catch him, and he stands in front of them in terror, gibbering and in tears. The two Greeks interrogate him, smiling, getting out of him any information they can, but he knows what is to come. He begs for his life, reaching up to the chin of Diomedes, asking for mercy, but Diomedes

strikes the middle of his neck

With a sweep of the sword, and slashes clean through both tendons,

And Dolōn’s head—still speaking—drops in the dust.

This is the most shocking moment in Homer, part of a hideous murder-run in the dark, with many dead, and booty taken, including wonderful horses and chariots, at the end of which Odysseus laughs aloud, has a swim in the sea and then a beautiful bath. Its amusement and delight at violence leaves a hollow in the reader’s heart, which is scarcely filled by the way the Greeks “vaunt” over the bodies of the people they have killed, calling them fools, telling the world of their own excellence, their right to stand over the dead and damaged body of the rival. This is also how gangsters “trash talk.” “I got your punk ass,” Bobcat tells one of his victims, “and now look at you … Now if you’d paid this cheese [money], you’d have been all right, but now you fucked up, you bleeding and shit … you talking about your ribs broke. Now what the fuck?”

Words are a way of making it hurt. This is the hero delivering justice, telling his victim, and his audience around him, just how powerful he is in the world. “Catching and punishing those who have wronged them makes offenders feel mighty,” Jacobs and Wright say, “while at the same time it masks their objective impotence.” “I had an adrenaline rush,” one of their informants told them about a particularly horrible piece of violence, “like I was the shit, like I was in control.” “I felt like I was in some pussy,” another said after using a baseball bat to break the legs of a man who had vandalized his car. “You know [like I] busted [a] nut”—or ejaculated.

This elision of self-enlargement, sexual gratification and extreme violence to other men’s bodies lurks in the subtext of Homer. A theater of sex and violence is at the heart of both the Iliad and the Odyssey: the stolen woman Helen; the twice stolen woman Briseis (once from her family, all of whom Achilles has murdered, once from Achilles, who comes to love her); the recurrent boast that the Greeks will kill the Trojan men and take their women, as they have taken other women from other cities; the sexual battening on Penelope by the suitors; the savage retribution exacted by Odysseus on those who have wanted to have sex with Penelope, and then on the women of his own household who had had sex with those suitors. This is a core reality in Homer, which finds its explicit echoes in gangland.

Colton Simpson, from South Central Los Angeles, was fourteen in 1980. His mentor Smiley, his “road dog,” his running mate, glows to him like a hero, just as Achilles and every Indo-European hero has always glowed: “When he smiles it’s as if the light, the sun behind him, fills me, fills each and every one of us standing there before him.”

When the law is no good, the only justice that makes sense is retaliatory, and that is the governing ethic of the Greeks in the Iliad. It is the dark heart of the gang on the beach, where personal affronts attack identity, where counterstrikes tend to be excessive, where minor slights are interpreted as major blows to character, where warriors rely on the honor that accrues to those who demonstrate prowess in disputes, where honor is accumulated much like real capital and bringing someone down for what he did to you raises your worth in the eyes of your peers, where intolerance earns respect and strength is protective. Every one of those phrases in italics is used by Jacobs and Wright to describe life in the murderous slums of St. Louis, Missouri; every one also describes the world of the Iliad.

The city itself floats in the half distance, a dream world of order, where the warrior is not constantly under test, where he can rely on those who are around him and who love him. The marginalized gang members, shut out beyond its walls, can only look on with envy and loathing.

Violence in the warrior gang is a means to survive and prosper. Without violence they would shrivel and fade, beaten by the city, by the pointy heads and the Brahmins. Violence is only doing what justice requires them to do. Violence is their destiny. And it should come as no surprise that these gangs must also have their epics. “No one forgets who was killed where and for what purpose,” the Berkeley sociologist Martín Sánchez-Jankowski wrote. “Some Chicano gang members can tell you who was killed twenty years ago, before they were born, because this history has been passed down to them, these members have attained a degree of immortality, which mutes the fear of death and much of its inhibiting power.” The gangs treasure kleos aphthiton, deathless glory, because in their vulnerability and their transience, the way in which there is nothing beyond their bodies and the memory of their actions, they need it more than anyone who is lucky enough to live in the law-shaped, law-embraced, wall-girdled city.

There is a code of conduct within the gang, as there is among the Greeks. Neither rape nor fighting with weapons was allowable within any of the thirty-eight gangs studied by Sánchez-Jankowski. The same kind of sanction exists within the Greek camp, although the natural fissiveness of all gang life is reflected there too. Achilles and his men come within a whisker of leaving Agamemnon’s coalition. Nevertheless, there is a rawness in modern gang life and their talk—the gang term for a gaping wound is “a pussy”—from which Homer holds back. The LA gang world takes delight in the explicit elision of sex and violence, dominance and abuse, in a way that Homer buries and dignifies. The latent sexuality that is threaded through the poems never quite breaks the surface. Homer can be horrifyingly direct and concrete but is never ugly, as if the language has been washed and cleansed in the centuries over which the poems evolved. The trash talk of the Greeks on the beach is conveyed in terms that could be heard in the halls at Pylos. The words of the desperate men in South Central LA and East St. Louis perform some archaeology on that Homeric language, stripping away its civility, exposing the body and the suffering beneath; but that should not be seen as some kind of return to truth. Homeric truth, the meaning of Homer, is about the integration and fusion of qualities, the acquired wisdom of Homer knowing warrior rage intimately but seeing and hearing it through the words of the city.

* * *

For the Greeks, the great urban civilizations of the Mediterranean lay temptingly and glitteringly to the south, and you might wonder why, of all the places they might have chosen for their encounter with the city, Troy became Homer’s focus. Is there any evidence that in the years of the Greek arrival, in the centuries around 2000 BC, Troy was the site worth sacking?

It was certainly not the richest, biggest or most powerful city of the Near East. Seen from the churning dynamos of money and power in Egypt and Mesopotamia, or from the great port cities of the Levant, Troy, on the far northwestern corner of Anatolia, can have looked like little more than a regional outpost of the urban world, a place that did indeed have a citadel and a lower city, but which was nevertheless on the very margins of the urban universe. But seen from the other direction, “in the eyes of its northern neighbours,” as the Oxford and Sheffield archaeologists Andrew and Susan Sherratt memorably put it, “Troy must have been the brightest light on the horizon.” It sat at one of the great crossroads of antiquity, performing the role later filled by Byzantium-Constantinople-Istanbul, controlling the routes between both the Aegean and the Black Sea and Anatolia and southeast Europe. The persistent north winds that blow across windy Troy, and a steady north–south current through the Dardanelles, meant that no sail-driven ship could make its way north there. Every cargo had to be landed. Every precious object coming west from Anatolia of necessity passed through this four-point pivot. Every movement from the north into the Mediterranean, and every Mediterranean desire to reach the Danube, the gold of Transylvania, the great rivers of the Pontic steppe and the copper mines that lay beyond them, or the metals coming from the Caucasus—all had to come through Troy.

The great Trojan treasures found by Heinrich Schliemann are now in Russia, where they were taken by the Soviets at the end of World War II. The silver and gold vessels, the bronze, the jewelry and the astonishing carved stone axes were buried in Troy perhaps as early as 2400 BC or as late as 1800 BC. Schliemann named what he found “Priam’s Treasure,” and from the very beginning was ridiculed for imagining that the levels of the city in whose ashes they emerged, Early Bronze Age Troy II, a thousand years or more before the conventional date of the Trojan War, could have had anything to do with Homer’s Trojan king.

But just as at Mycenae, Schliemann’s suggestion is worth considering. He had found a burned layer along with a gate and a tower, and considered them “the ruins and red ashes of Troy.” In just the same way, his assistant Wilhelm Dörpfeld later settled on Troy VI, destroyed in about 1300 BC, and the Cincinnati archaeologist Carl Blegen came down in favor of Troy VIIa, which came to an end soon after 1200 BC. That remained the modern consensus under the huge German excavations from 1988 to 2003 led by Manfred Korfmann. But, as the British archaeologist Donald Easton has written, these were “three different sets of material evidence all supposed to prove the same identification and authenticate the same event.” There is nothing to associate Homer with any archaeological remains at Troy. The only pointer toward a date around 1200 BC is the guess made by Herodotus in his history. But his guesses, and those of other classical Greeks, were stabs in the dark at a time when no one knew how to date the distant past. There is certainly no better reason to associate Homer with the Troy of about 1200 BC than with a city a millennium earlier. And if finds are anything to judge by, the later Troys seem to have been poorer than the city Schliemann identified as Priam’s. Just as it is possible to imagine that the warriors in the Shaft Graves at Mycenae are themselves not the ancestors of the Homeric heroes but their sons and grandsons, there is nothing inherently unlikely in Schliemann’s suggestion that the Trojans of about 2000 BC were living in the city to which the Greeks laid siege.

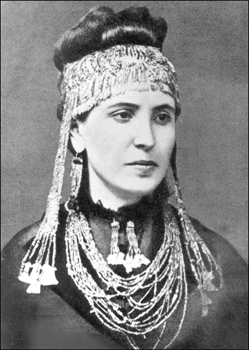

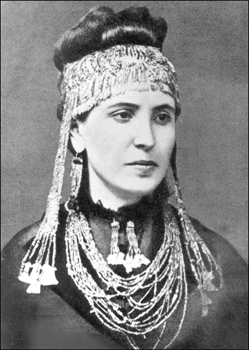

Sophia Schliemann, aged twenty-two, wearing “The Jewels of Helen,” Athens 1874.

Nothing found in later levels of Troy can in any way match what Schliemann found here. It was a mass of gold and silver: six gold bracelets, two gold headdresses, one gold diadem, four golden basket-earrings, fifty-six golden shell-earrings, and 8,750 gold beads, sequins and studs. The jewelry was probably made in Troy. A great deal of evidence for smelting and casting has been found in the city. But these treasures are also signs of Troy’s connections north and south. The tin the Trojans used for their bronzes probably came from Afghanistan. The beautiful golden basket-shaped earrings which Schliemann found are identical to others that have been found in Ur in Mesopotamia. There is amber here from Scandinavia, even a bossed bone plaque of a kind found at Castelluccio in Bronze Age Sicily.

Troy was the great entrepôt at the interface of the northern and southern Bronze Age worlds. The only way that Afghan tin and the Mesopotamian ways of working gold could have made their way to Bronze Age Transylvania and Hungary was through the Trojan gateway. No equivalent of Troy existed farther north or west. Only the palace center at Knossos in Crete could rival the extent of Troy in the centuries after 2000 BC. Just as the Vikings and the Crusaders would later lust after the riches of Byzantium and Constantinople, the Greeks longed for Troy.

Another treasure, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and with an obscure history, provides yet more spectacular hints at what any Greeks, or proto-Greeks, might have found at Troy if they had arrived there in the centuries around 2000 BC. The Boston treasure seems to have come from “northwest coastal Turkey,” the province of Troy itself. It was made in about 2300 BC and consists of the gold ornaments to be buried with a noble woman: heavy lion-headed gold bangles, sun and moon disks to decorate a dress or headdress, golden pins, hair rings and diadems, finger-rings and gold ribbons.

These objects add to the reality of early Trojan glamour, but the most intriguing aspect of them is that they are probably Egyptian or made by an Egyptian craftsman who had come to Troy, perhaps bringing Egyptian gold, to decorate a queen of Troy in a way she knew she deserved. He brought with him the motifs of the crouching lions and the lotus flower which were familiar at home in the Egyptian Old Kingdom, and which came north trailing clouds of imperial glory.

Of all the objects that might be thought contemporary with the arrival of the Greeks in the world of cities, none can match the dazzling, hieratic power of the four Trojan hammer-axes that are now in Moscow. They are wonderful, high-polish, metal-mimicking, power-concentrating objects, three in a kind of jade, one in beautiful, gold-flecked Afghan lazurite. They were stolen by Schliemann in 1890, the last year of his life, from the part of the site at Hisarlik that belonged to his rival and enemy, the English diplomat and antiquarian Frank Calvert.

But the squalor of that recent history is somehow appropriate. Schliemann named his son Agamemnon and in that choice declared himself the heir of “the greediest, most possession-loving of men.” You only have to look at these hammer-axes to feel some kind of desire to own them. Their smooth, cool solidity, the creamiest of surfaces in the hardest of materials, was surely designed for display and allure, even for envy. The beauty of violence is embedded in the ritual of their presence. Look at them with any kind of object-lust, and you will find yourself looking through the eyes of Agamemnon.

Here in these objects, smuggled out of Turkey by Schliemann, legitimately wanted by the Turks, held on to by the Germans, hidden by the Nazis, taken by the Russians, then hidden again for almost fifty years, now also claimed by the distant heirs of Frank Calvert, you can see, far more than in the dusty, abused walls of Hisarlik, exactly what the marauding Greeks were after. Everything here concentrates a power which it then emanates. This is beauty and exoticism as instruments of control, embodying the core function of a great city, drawing in the rich and strange, then displaying it as a sign of dominance.

* * *

If the plain on which the Greeks are camped is the zone of severance and “the pitiless bronze,” the city is the realm of jointness and connection, a place for weaving. In Troy, woven cloth becomes the medium for Homer’s story. And in that detail there is an astonishing linkage between the archaeology of Troy and the city portrayed in the Iliad. From Schliemann onward, archaeologists have found powerful evidence of an almost unparalleled scale of cloth-making in the city, at all levels of Trojan society. In the ashes of Troy II, which Schliemann identifed as Priam’s city, he found a small round clay box and in it the remains of a linen fabric decorated with tiny blue-green faience beads and a spindle full of thread. Carl Blegen in the 1930s found hundreds of tiny gold beads around the remains of a loom that had been set up with a half-finished cloth on it. And in Troy as a whole, these early levels of the city have produced over ten thousand clay spindle whorls, small weights attached to a spindle, whose momentum helped the process of spinning. It is a historical truth that Troy spun and wove.

When Helen first appears—the woman at the heart of the story, the Greek who was stolen by Paris the Trojan prince, whose infidelity began the war, who has come to love the Trojans but still longs for her homeland, who feels guilt and passionate desire for Paris but regret for the home and family in Greece she lost, who is in other words an amalgam of severance and connection—she is in the hall of her house weaving.

On her loom is “a great cloth” that is called marmareën in some versions, in others porphyreën. These are powerful, laden words, both intimately connected with her history and with the sea. Marmareos can mean “gleaming or twinkling like sunlit, wind-stirred water;” porphyreos “heaving,” “surging like a sea swell,” “gushing like blood,” “pouring in like death in battle,” “lurid like a rainbow,” which for the Greeks was a portent of bad things to come, or “purple like the ink of the cuttlefish.” It is as if Homer concentrated in those phrases the whole sea-tragic story of the war, and Helen’s own catastrophe within it. Into the weft of her cloth, of a double fold, she is working many woven images “of the endless bloody struggles/the horse-taming Trojans and the bronze-armed Greeks/had suffered for her sake at the god of battle’s hands.”

Helen, even as she remembers the source of her grief, becomes like Homer the weaver of the tale. As he tells it, she is weaving it. Dressed in shimmering linen, with two of her attendant girls beside her, she goes to the ramparts of the city, where the old men, singing like cicadas in the treetops, look at her and see in her face “how terribly like the immortal goddesses she is to look on,” that pun on the destruction that beauty can bring embedded in the Greek. Then, amid the horror of war, looking down from the closed ramparts at the armies drawn up below them on the open geometries of the battlefield, Priam, the king of Troy, does the beautiful thing, drawing Helen near to him, binding her in, weaving the reassurances of civility around her.

Come over here, where I am, dear child, and sit down beside me,

To look at your husband of time past, your friends and your people.

I am not blaming you: to me the gods are blameworthy

Who drove upon me this sorrowful war against the Achaians.

This is love as a kind of weaving, a bringing together of the things that war has separated. The shuttle of the weaver travels to and fro, but the blade merely plunges in. The making and maintaining of a city is a multiple act, reflexive and responsive, in the way that the killing of an enemy, the one-way journey of a soul out through the teeth and down to Hades, could never be. That is why the offering that the Trojans make to the great goddess Athene is made of cloth.

The queen herself goes down to the vaulted treasure chamber where her robes are, richly embroidered, the handwork of women from Sidon, on the far eastern shores of the sea, whom Paris himself has brought from Sidon, as he sailed over the wide sea on that journey on which he brought back high-born Helen … The best and the thickest with the finest embroideries, which shine like a star, gleaming and brilliant, they take as an offering to Athene.

These are the treasures of the innermost place in Troy, the thalamos. These are its essential materials. It is a place of women and children, rich with fineness brought from the east, from the great urban civilizations of which Troy was the farthest outpost, far to the northwest, of their heartland in West Asia and Egypt. Here too, Homer is describing the meeting of worlds. This is what lies at the heart of the distant towers seen from the Greek camp on the shore, and it is here that the poem demonstrates its love and admiration for the marvelousness of women and womanliness.

In the Greek camp, women are traded as commodities. A woman and a tripod are put up in one lot as a prize for a chariot race, where a tripod is thought to be worth twelve oxen and a good serviceable maid-of-all-work four. That is not the atmosphere in Troy or in the most erotic scene in the Iliad, where Hera, the queen of the gods, prepares herself for love. Troy is much closer than the Greeks to the gods. There is a shared atmosphere between the city and Olympus, and the beauty of cloth, the essentially Trojan material, slides easily over into heaven. Alongside the delicious ointments with which Hera burnishes her body, she dresses slowly, seductively. It all happens inside her private chamber on Olympus, the doors closed with a secret bar, a female inwardness. She smoothes her body with exotic oils, the perfume drifting down from heaven in a mist of scented rain over the surface of the earth, while around her shoulders she wraps the “ambrosial robes” that Athene has made for her. They are smooth and satiny, with many figures embroidered on them, and she pins them across her breast with a golden brooch, circling her waist with a sash, before borrowing from Aphrodite, the goddess of love, the magic breastband which has woven into it all the hidden powers of longing and desire, “the whispered words that can steal the heart from any man.” Weaving knows secrets which the heartless bronze could never hope to grasp.

There is a wariness in Homer about these delicious feminized delights of the city. They are not from the world of the warrior on the plain. When Nastes of the Karians, one of the Trojan allies from elsewhere in Anatolia, turns up for battle like a girl for a party, in golden clothes, “poor fool,” he is soon dead: “He goes down under the hands of the swift-running Ajax and fiery Achilles strips him of his gold in the river.” It is a wet, messy killing as Achilles, the agent of nature, takes his revenge.

Alongside pathetic Nastes is Paris, whose lust was the cause of the war, and who is now an empty urban fop, a pretty boy, beautiful, woman-crazed, a Hollywoodized warrior, happier in scented rooms, in bed with his beauty, than out fighting where his city might need him to be. His helmet is embellished with a richly embroidered chin strap, with which he is very nearly choked to death by a Greek, before a god rescues him and whisks him away to his boudoir. Homeric distrust of the potential for unmanliness in the city, whose beauties and order are nevertheless deeply desirable, is never far beneath the surface.

These polarities sharpen as the war deepens. The Greeks become increasingly animalistic. The Trojans are increasingly identified with the great walls that will save them from the savages at their gates. Group battle scenes give way to a sequence of individual tragedies. The shedding of blood is now close-focus. Dark underlayers bloom, and a persistent suggestion heaves up, just beneath the surface, that these men are cannibals.

Something of this has been there from the start. Agamemnon has said that the Greeks should not hesitate to kill Trojan babies. Zeus accused Hera of wanting to walk in through the gates of Troy and eat Priam and his children and the other people there, to take them raw, to glut her anger. But by the middle of the poem, the levels of body-abuse have steepened and animality has entered the battle.

Idomeneus stabs Erymas straight through the mouth with the pitiless

bronze, so that the metal spearhead smashes its way clean up through

the brain, and the white bones splinter,

And the teeth are shaken out as he hits him and both eyes fill up

With blood, and as he gapes he spurts blood through his nostrils

And his mouth, and death’s dark cloud closes in about him.

The Myrmidons, the men Achilles has brought here from Phthia, are

like wolves, who tear at raw flesh,

in whose hearts battle-rage knows no end,

who have brought down a great antlered stag in the mountains,

and then feed on him, till their lips and cheeks are running with blood,

and who then move off in a pack, the crowd of them,

to drink from a spring of dark water,

lapping with their narrow tongues along the black edge of the water,

belching up the clotted blood, their bellies full and their hearts unshaken.

The Greeks begin to lose the fight. Achilles refuses to stir from his tent. His beloved Patroclus takes his armor and wears it so that the Trojans might think Achilles himself has returned to the battle. The trick works, the Trojans take fright and Patroclus starts to push them back from the ships. But he goes too far; Hector kills him, and he lies dead in the dust. Standing over his body, in the midst of battle, Hector makes the great statement of the city against the plain.

Patroclus, you have thought perhaps of devastating our city,

Of stripping from the Trojan women their day of freedom

and dragging them off in ships to the beloved land of your fathers.

Pea-brain!… Now vultures will eat your body raw.

Idiot! Not even Achilles can save you now.

The armies fight over the body of Patroclus with a new and horrible intensity, a struggle that lasts for hundreds of lines. In the fight, the beautiful Trojan Euphorbus is killed by Menelaus, and his lovely hair, braided with gold and silver, like the body of a beautiful wasp, is soaked and clotted with blood, civilization drenched in war. Menelaus now, with the battle frenzy in him, is like a mountain lion that has caught a delicious cow, the best cow, and is “mauling the kill, gulping down the guts that are inward.” Hector strips the armor from Patroclus, the glorious armor which Achilles had lent him, and drags at the body, meaning to cut the head from the shoulders “and give the rest to the dogs of Troy.” He promises huge rewards to those who can drag back to the city the now naked body of Patroclus, who has become nothing but flesh, stripped of meaning, meat for the dogs and birds.

The Trojan warrior Hippothoos—the name means “Quickhorse”—tries to get the straps of his shield around the tendons in Patroclus’s ankle so that he can pull him back to the dog-feast in the city, but Ajax shafts him in the head, and Quickhorse’s brain “oozes out from the wound along the socket of the spear, all mingled with blood.” In this horror flensing-yard scene, a Greek dies with a spear under the collarbone, a Trojan with a sword in the guts “so that he claws at the dust with his fingers,” and another Greek with a spear in the liver under the midriff.

The desperate struggle is for the flesh of Patroclus, simply to possess his physical remains, the grisliest possible tug-of-war, stretching the body in the way people pull and stretch at an ox hide to make usable leather of it,

with so many pulling, until the bull’s hide is stretched out smooth,

so the men of both sides in a cramped space tug at the body

in both directions; and the hearts of the Trojans are hopeful

to drag him away to Ilion, those of the Achaeans

to get him back to the hollow ships.

On different warriors, the blood runs from their hands and feet, “as on some lion who has eaten a bullock.” Menelaus is like a mosquito “who though it is slapped away from a man’s skin, even / so, for the taste of human blood, persists in biting him.” Hector, hanging on to the body of Patroclus like “a tawny lion who cannot be frightened away from a carcass he has in his claws,” is desperate to pull the body back to Troy so that he can “cut the head from the soft neck and set it on sharp stakes.” This is not your elegant, noble, neoclassical Homer. This is rawness itself. Bloodthirsty Arēs, the god of war, the metaphor not yet dead, has become the governing force in a battlefield that wants more than anything else to drink human blood.

This is the environment into which Achilles now drives, grief-mad from the death of Patroclus. He will not eat, as civilized men sit down and eat, but wants to feast on the body of Hector. Like a man with a rifle at a fairground booth, he pops out death to twenty-three Trojans in a row: a spear in the middle of the head, a spear through the side of the helmet, another in the head, one in the back, one in the back and out through the navel, one in the neck, one in the knees with a spear and then finishing him off with a sword, one with a spear, another with a sword, one with a sword in the liver, a pike in one ear and out the other ear, a sword in the head, a sword in the arm then a spear in the arm, beheading with a sword “and the marrow gushes from the neckbone,” a spear in the belly and a spear in the back, and then seven men whose deaths are remembered only in their names.

As he wearies momentarily of killing, he takes twelve young men alive, to sacrifice on the pyre of Patroclus.

These bewildered boys, dazed like fawns, he drags away

And lashes their hands behind them with well cut straps,

the very belts they wear around their tunics,

And gives them to his companions to take to the hollow ships.

Then straight off in, raging to kill again.

He is beyond humanity now and has become “an unlooked for evil.” His sweetness and capacity for love have left him. To the pitiable Lycaon he talks with all the reason of a madman.

Now there is not one who can escape death, if the gods send

Him against my hand in front of Ilion, not one

Of all the Trojans and above all the children of Priam.

So, friend, you die too. Why moan about it?

Patroclus is dead, who was better by far than you are.

Do you not see what a man I am, how huge, how splendid

And born of a great father, and the mother who bore me immortal?

Everyone has to die, so why don’t you? “Die on, all of you,” he tells the Trojans, “till we come to the sacred city of Ilion, you in flight, and me killing you from behind.”

Even as the universe of the battlefield becomes a careless and pitiless place, the allure and goodness of the besieged city become ever more precious. This is where the grand spatial geometry of the poem comes to its sharpest point. Achilles is the untrammeled world of the plain. “I will not leave off my killing of the proud Trojans,” he says, “until I have penned them in their city.” He is polarizing the world he controls until they are indeed all running and shuffling toward the high, wide walls Poseidon built for them—all except Hector, their champion, who must remain out on the plain with his killer.

Homer binds the Trojans to the physical facts of their city. Priam, Hector’s father, the human embodiment of Troy’s virtues, becomes coterminous with the city’s walls and gates.

The aged Priam takes his place on the god-built bastion,

And looks out and sees, gigantic Achilles, where before him

The Trojans run in their hurry and confusion, no war strength

In them. He groans and descends to the ground from the bastion

And beside the wall sets to work the glorious guards of the gateway:

“Hold the gates wide open in your hands, so that our people

in their flight can get into the city, for here is Achilles

close by stampeding them.”

This is the Iliadic confrontation at its sharpest. The city gates must close the Trojans in while Achilles is out in the plain, “fierce with the spear, strong madness in his heart and violent after glory.” Everything in the Iliad comes into pincer-intimacy in these lines. The warriors join their “beloved parents, wives and children” inside the gates, “For they dare wait no longer outside the walls and the city” because on the plain Achilles is running free and dangerous across the open ground. Only Hector, the isolated Trojan, remains outside the walls, “shackled by destiny,” awaiting the climactic meeting with the inhuman violence of the gang-man Achilles.

Metaphorical geography has the poem in its grip here. This is not the meeting of Achilles and Hector; it is the deathly confrontation of two ways of understanding the world. The key words clang through the poetry: “city,” “battlements,” “walls,” “Ilion,” “gates,” “crowded,” “city,” “wall” and “city” again, all within twenty lines of the beginning of book 22, and all set against that other world, the flatlands, the open plain, the pedion, over which Achilles runs like a prizewinning chariot horse, half-human, gleaming, looking like the Dog Star, a beacon of hate, sheathed in metal, the bronze in which he seems to be made shining brighter than any other star, a being radiant with horror, bringing evil and pain to men.

Homer never seems more real or more terrible than when Priam stands on his walls and talks pleadingly down to his son Hector standing outside the gates below him. Hector is terrifyingly alone, when the understanding of Trojans is that community is safety. “Come into the walls, my child,” Priam says to him, “so that you might save Trojan men and Trojan women.”

And then the old king makes a speech of Shakespearean poignancy and power.

I have looked upon evils

And seen my sons destroyed and my daughters dragged away captive

And the chambers of marriage wrecked and the innocent children taken

And dashed to the ground in the hatefulness of war, and the wives

Of my sons dragged off by the accursed hands of the Achaians

And myself last of all, my dogs in front of my doorway

Will rip me raw, after some man with a blow of the sharp bronze

Spear, or with spearcast, has torn the life out of my body;

Those dogs I raised in my halls to be at my table, to guard my

Gates, who will lap my blood in their savagery and anger

And then will lie down in my courts. For a young man all is decorous

When he is cut down in battle and torn with the sharp bronze, and lies

Dead, and though dead all that shows about him is beautiful; but when an old man is dead and down, and the dogs mutilate

The grey head and the grey beard and the parts that are secret,

This for all sad mortality is the sight most pitiful.

The dogs eating his genitals, like blood on the gold-laced hair, is Priam’s vision of the triumph of Achilles, the triumph of the gang over the city, the anarchy of violence over the generations of people and the bonds which tie them. Hector’s mother, Hecabē, from the parapet above, holds out her breasts to him, bared and open. “Sweet branch,” she calls to him, “child of my bearing,” “look upon these and obey. From inside the wall beat off this grim man.”

Hector’s sense of honor, his debt to his city, will not allow him to go inside “the lovely citadel,” and the fatal race begins. He and Achilles run round and round the walls, Hector in flight, Achilles in pursuit. It is like a dream, Homer says, when your running brings you no closer to your prey, nor takes you farther from your terror-pursuer; and it is a dream hell out on the plain, where there can only ever be one destiny. Sometimes Hector shelters under the walls, but Achilles gets between him and the wall “and forces him to turn back into the plain.”

With unrelenting consistency, Homer applies his geography: city is goodness and connection, plain is horror and terror; city is Hector’s weakness, plain Achilles’s strength; city is the realm of the Trojan families, their women and children, while the plain belongs to Achilles alone—during this climax of grief the other Greeks have disappeared from view.

When finally Hector pauses, tricked by Athene, Achilles catches up with him and they talk. Achilles plunges for cannibalism. I want, he says, “to hack your meat away and eat it raw for the things that you have done to me.” There can be no surprise. Achilles spears Hector in the soft part of the neck, just where the armor opens a little white mouth of skin, “and clean out through the tender neck goes the point.” After killing him, he abuses Hector’s body by dragging it fast behind his chariot. Hector’s hair and head are tumbled and wrecked in the dust, and this physical action is the emblem of the gang-man’s triumph, the imposition on the man of the city of the dirt of the plain.

With Hector’s death the city’s fabric is irreparably torn. Hector’s mother casts aside her “shining veil.” His wife, Andromachē, does not at first hear the news. She is weaving a cloth in the inner room of her high house, a red folding robe with figures embroidered on it, not unlike the cloth Helen had been working so many thousands of lines ago. Andromachē calls out to her handmaidens to prepare a bath for Hector, for when he comes back from the fighting. Then she hears the mourning and wailing of the other women, and the shuttle with which she had been weaving drops from her hand. Running to the ramparts, she sees Hector’s body dragged around the city walls, his head in the dirt, Achilles triumphant. She collapses, “gasping the life breath out of her,” while all the woven things fall from her, the circlets around her head and breast, the cap she is wearing, even as the threads of Troy tighten around her and “her husband’s sisters and the wives of his brothers hold her up among them.” In their house, she then remembers, there are all kinds of clothing, “fine-textured and pleasant, wrought by the hands of women,” ready for Hector. “All of these I will burn up in the fire’s blazing,” Andromachē says. “They are no use to you.” The woven and the severed; the heart of Homer’s meaning.

* * *

The Iliad might have ended there, with the victory of the plain over the city, but it doesn’t. Troy is about love, children and home. Its lifeblood is in the virtues of human community, of not claiming the ultimate against your enemy but finding it in you to say that, whatever he has done, humanity is shared. Troy is a desire for wholeness, a desire that wholeness might survive the necessary violence, that there is no “tragedy of necessity.”

The poem ends before Troy falls, but Homer orchestrates something subtler and richer than the hideousness of any military triumph. After Achilles kills Hector, the whole of the city goes into horrified despair and mourning. The women wail, the men cover themselves with dung scraped up from the streets. This moment of hopelessness is the pit of the poem. Achilles is still threatening to eat Hector’s body raw. It looks as if everything the city enshrines means nothing in the teeth of the Greeks’ triumph. Priam resolves to go to their camp across the plain to find Achilles and beg him for the body of his son.

The old king slowly prepares and gathers carts full of the best that Troy can offer, including beautiful cloths: robes, mantles, blankets, cloaks and tunics, as if wanting to drown Achilles in the woven. But that is the point. Priam is going to take the city out into the plain. That has been the place where in book after book, death after death, the wrong thing has been done. Priam’s journey is a kind of healing laid across that theater of horror. He travels slowly, at night, with his mule carts; no heroic northern chariots here. He comes at last into the shelter of Achilles’s camp, and without announcement the old king kneels down next to Achilles, clasps his knees and “kisses his hands, the terrible man-slaughtering hands, the hands that have shed so much blood, the blood of his sons.” That old man’s kiss is the moment of arrival. Achilles thinks of his own father in Phthia and comes to understand something beyond the world he has so far inhabited. Both men give way to grief.

Priam weeps freely

For man-killing Hector, throbbing, crouching

Before Achilles’s feet as Achilles weeps himself

Now for his father, now for Patroclus

And their sobbing rises and falls in the house.

Food is cooked for them, mutton souvlaki.

They reach down for the good things that lie at hand

And when they have put aside desire for food and drink

Priam gazes at Achilles marvelling now how tall he is,

And how beautiful

And Achilles looks at the nobility of the old king

And listens to his words.

They gaze at each other in silence, and that exchange of admiring looks is the Iliad’s triumph. Priam has brought the virtues of the city into Achilles’s heart. Hector will now be returned to his father and will be buried with dignity outside the city. In that way, Troy has won the war. Achilles, the man from the plains, has absorbed the beauty of Priam’s wisdom, of his superhuman ability to admire the man who has killed his sons, and from the mutuality and courage of that wisdom, its blending of city and plain, a vision of the future might flower. Achilles will soon be dead, Troy will soon be broken, the Trojan men will soon be slaughtered, Priam among them, horribly murdered by Achilles’s own son, their women abused and enslaved, but here, in poetry, in passing, a better world is momentarily—or in fact everlastingly—seen.