LIVING AND WRITING IN KUWAIT: WHAT FICTION CAN DO

Mai al-Nakib

WHAT IS LIFE LIKE for writers living and working in the Middle East? A straightforward question and yet one that is not at all easy to answer. Television and internet images make it seem as though the dominant feature of the region is that it is forever in a state of crisis. Needless to say, many of us have a legitimate bone to pick with media representations of the Middle East. However, if I’m honest, living in Kuwait as I do, it often does feel as though the world around me is on fire, on the brink of catastrophe or already there. The ongoing crises during the summer of 2014 in Gaza, Syria and Iraq are only the latest in the serial tragedies that have gripped our region.

The Gulf states might appear to be relatively calm by comparison – an air-conditioned bubble in the midst of hell. This is a mirage. First of all, there can be no real peace of mind for anyone with an ounce of humanity in them as long as the brutal suffering in the region continues. Even if you do not happen to have bombs falling on your particular head today, you can’t help but put yourself in the place of those – not so far away, not so different from yourself – who are not as lucky. And while it might be easier for Qatar, the Emirates and Saudi Arabia to allow themselves to believe it could never happen to them, it should be impossible for Kuwait to do so, given its own encounter with war and occupation in 1990–91.

Second, while perhaps not overtly in crisis, the Gulf states nonetheless thrum beneath the surface with a disparate range of problems that could erupt in the not too distant future. Reliance on a single resource is, perhaps, the most obvious concern, but other issues include demographic imbalances, fundamentalisms, sectarianisms, political disenfranchisement, environmental ruin, obesity and diabetes, masked unemployment, labour exploitation, a failing system of education and hyper-consumerism. The current state of affairs is unsustainable both materially and ethically. Gulf citizens may bury their heads in the sand but, soon enough, these issues will surface, and it doesn’t take an expert to recognise that the cumulative outcome will be grave.

So, amid seemingly endless regional disasters and local difficulties, how does a writer write? With the stresses and sorrows of war, the anxiety over bleak future projections and the guilt of knowing that people nearby are experiencing intolerable suffering, how does a writer from my part of the world manage it? I can attempt a response to this question by addressing another one: what can fiction do? As a professor of English and comparative literature, this question is always on my mind as I teach students and reflect on the relevance of my research. As a writer of fiction, it is a question that informs everything I write. In brief, as far as I’m concerned, the special function of fiction is to invent worlds, to imagine alternatives to the present, to conjure up what Edward W. Said, in a different context, describes as ‘eccentric angles’, in order to remind us of our shared interests, if not our shared humanity.1 Fiction can produce these effects in a myriad of inventive ways, some of which may include revisiting forgotten elements of the past; producing the conditions necessary for readers to inhabit different modes of life; and drawing attention away from a dominant order that often seems to choke off any sense of possibility. One way to convey this function of literature is through my specific experience as a Kuwaiti writer.

I was a child in Kuwait in the 1970s and came of age there in the 1980s. For me, those decades mark Kuwait’s golden years. Of course, this is a view tainted by nostalgia; it is politically and historically inaccurate. In fact, those decades were marked by the Iraq–Iran War; the Souk al-Manakh stock market crash; the rise of Islamic fundamentalism; the clampdown against segments of the Kuwaiti population, the Shia community in particular; and the policy of Kuwaitisation, which threatened members of the non-Kuwaiti population, including Palestinians. Still, as a teenager growing up in the 1980s in Kuwait, I experienced some of the residual cosmopolitanism that had characterised the country’s previous history. It is this currently ignored characteristic of Kuwait that I attempt to revisit in some of the stories that appear in my book The Hidden Light of Objects.

Kuwait was a thriving commercial port town from the 1700s. Accustomed to travel and movement, its population – whether seafarers or Bedouin, rulers or merchants – developed canny negotiating capacities and expressed a decidedly outward-looking slant on the world. Historically, it is fair to say that Kuwait and its population have tended to be globally interactive, managing to maintain autonomy over the centuries, walking a precarious tightrope across the Ottoman Empire, central Arabia, Britain and Iraq. I would argue that Kuwait’s past successes were a result precisely of its outward-looking, engaged, generally tolerant sensibility. This particular point of view also defined the early years of Kuwait’s establishment as a modern nation-state. From the 1930s onwards, up until the 1970s, Kuwait welcomed people in, tended not to see them as outsiders but, rather, as participants in the development of a shared country. We know this because in the 1950s and 1960s Kuwaiti citizenship was offered to individuals of various nationalities in a way that would never occur today.

I must insert a caveat here in order to prevent myself from slipping too far into the dangerous trap of nostalgia. Kuwaiti political scientist Abdul-Reda Assiri has argued that over time Kuwaitis developed what he calls a ‘siege mentality’, which emerged as a result of real threats to the state’s survival.2 For example, immediately upon declaring its political independence in 1961, Kuwait was threatened by Iraq with annexation. This threat was countered by British military protection, as well as – paradoxically – the support of 2,000 Saudi troops. I say ‘paradoxically’ because historically there had not been much love lost between the two nations or their leaders. From the Wahabi attacks against Kuwait from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries, to the Uqair Protocol of 1922, which saw Kuwait lose two-thirds of its land to Saudi Arabia by way of the British, to crippling trade sanctions imposed by Saudi Arabia against Kuwait from 1928 to 1937, the relationship between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia has been fraught, to say the least. The vexed nature of this relationship has been overshadowed by the more recent hostilities from Iraq. Needless to say, the 1990 invasion did nothing to ease this Kuwaiti disposition. Still, Assiri suggests that, despite its defensive inclination, what kept Kuwait reasonably stable and secure over hundreds of years was the ‘external outlook’ of its population, shaped by the country’s ‘interaction with faraway lands and people’.3

In the 1970s, this more open sensibility still dominated my parents’ generation. My parents and their contemporaries were taught mainly by Palestinian teachers at primary, secondary and university levels. Many of that generation continued their education abroad and most, if not all, then returned back to Kuwait in their prime, eager to build their country according to the exciting range of images and experiences collected along the way. Furthermore, it was a sensibility passed on to their children, those of us who grew up in the 1980s. As was evident in the streets of Salmiya or Hawalli or among the student bodies at international or even government schools, the texture of our community was decidedly varied and complex and, for the most part, it was harmonious.

After 1991, however, Kuwait’s historical cosmopolitanism began to recede and its ‘siege mentality’ to intensify. In some ways, a more inward-looking attitude is understandable. Interactive policies and tolerance appeared to have brought nothing but catastrophe to the country and its citizens, so it was believed that something drastic and different needed to be done. Cosmopolitanism, it seemed, had been part of the nation-state’s downfall, so something else needed to be slotted in its place. Expulsion, restriction and purity were chosen over inclusion, openness and plurality. In the last two decades, however, that alternative has proved to be even more catastrophic than the original crisis that initiated the shift away from cosmopolitanism. Since 1991 at the very latest (arguably even a decade before that), the relative stability enjoyed by Kuwait since the 1700s has come undone on many fronts – political, social, economic, cultural. This is not the place to enumerate all the various crises Kuwait has been through in the last two and a half decades, but a few examples would include the routine dissolutions of parliament since 2006; the disenfranchisement of the bidoun (those without citizenship); the escalation of tensions between the government and various opposition groups; an intensification of sectarian divisions; a worrying increase in violence; ongoing human rights concerns regarding expatriate labour as a result of the kefala (sponsorship) system and lack of protection; the marked decline in educational standards; an increase in health issues and the inability of the health-care system to keep up with demand; the traffic fiasco; and, above all, the predicament of dependency on a single natural resource. Something to consider is whether the absence of the cosmopolitanism that buoyed Kuwait through previous crises, excised post-1991, leaves the country ill-equipped to address the seemingly insurmountable crises suffered today.

Robert J. C. Young has argued that the Convivencia in Cordoba – the period of religious coexistence among Muslims, Jews and Christians in southern Spain that began under Caliph Abd-ar-Rahman III, who ruled from 912 to 961 – stands as an exemplary model of multicultural tolerance and of ‘communal living in a pluralistic society’.4 He suggests that such forms of multiculturalism continue to exist in some Gulf states even today. I would argue that historical Kuwait town and Kuwait as a young nation-state retained aspects of this key feature. Convivencia was sustained, Young points out, not by the erasure of difference or homogenisation in the name of nationalism or religious purity. On the contrary, as he explains, ‘The state becomes stronger through the tolerance of heterogeneity, weaker by repressing it.’5 Sadly, the validity of this paradox seems regionally and globally unintelligible, or perhaps just unacceptable.

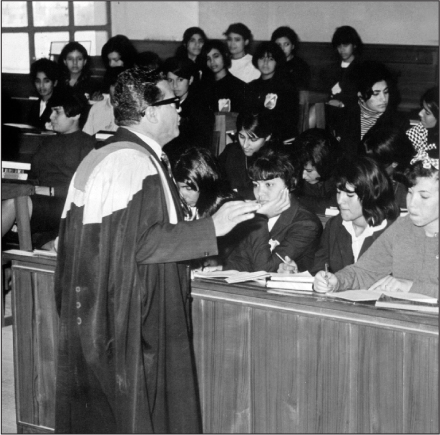

Kuwait University students in the 1960s. Kuwait, by Oscar Mitri (Kuwait: Government Press, 1969), p. 17.

This was certainly the case in 2004, when I started teaching at Kuwait University. It became abundantly clear to me that any residue of the cosmopolitan Kuwait I grew up in was not only gone, but that its memory was being systematically obliterated. This was happening at an alarming rate on many fronts: in education, in the urban landscape, in the shifting demographic, in politics, culture, clothing, language and so on. It seemed almost as if we, citizens of Kuwait, were slipping into a state of amnesia. For example, while discussing a collection of photographs of Kuwait by the well-known Egyptian photographer Oscar Mitri with my undergraduate students during that first year, I was startled to discover just how unfamiliar Mitri’s Kuwait seemed to them. The book, printed by the government in 1969 and titled, simply, Kuwait, featured, among many other images, a religious ceremony at the Roman Catholic church, women waterskiing along the shore and a class of female university students, not one of them wearing the hijab. My students, the majority of whom were wearing the hijab, were baffled, as was I, though not for the same reasons.

This shift in outlook felt incredibly stifling to me, and one reason I turned to fiction was as a way to open a window, a vignette on to something else. My short stories attempt to revisit this forgotten or stifled cosmopolitanism in Kuwait and the wider region in an effort to imagine alternatives to the present, a different kind of home. Although my academic writing engages similar concerns, fiction possesses a flexibility and potential reach that make it particularly appealing. In any case, at the time it felt like no matter how many articles I wrote, none could match the visceral effect of fiction, my first love.

In some ways, it is impossible to escape the traces that make us who and what we are. We are born in a particular place, into a specific family with its own distinct history. We grow up inhabiting a certain language, among a defined community of people. All these elements, among others, shape us and our perspectives on the world. For a writer, these traces pierce through the writing in one way or another. It is impossible to think of Márquez without Colombia, Rushdie without India or Mahfouz without Egypt. Nonetheless, fiction is the unique site where it is possible to escape or transform these very traces. It is true that these traces make us who we are, the kinds of writers we become. But the writing we do allows us to flee the confines of these determining factors, to imagine other worlds. For me, writing fiction became a way to recreate or reimagine a place I was convinced had once existed but that was now nowhere to be found. I needed to construct a space – a safe haven – where I could not only remember my version of the adventurous and mongrelised past, but also imagine a future other than the one that was being prepared for us by the rather rigid and extreme orthodoxies dominating the region post-9/11.

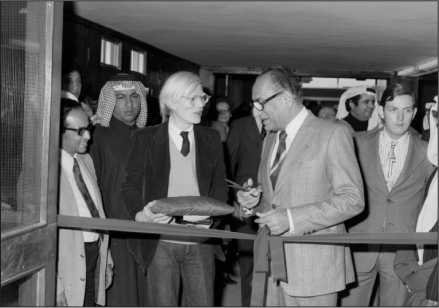

Fiction invites us to remember (or to experience for the first time) pasts that are different from the normative version of the past most expedient to current interests. If we take this function of fiction seriously, it opens up for us the chance to consider otherwise disregarded (sometimes discarded) futures. Memories, images or narratives that contradict or interrupt those offered up as definitive, as set in stone, remind us that the world need not proceed as it happens to be proceeding at present. In the context of Kuwait, for example, what would it be like to remember that Andy Warhol exhibited at the Sultan Gallery in 1976? Or to remember that at the Gazelle Club, among other venues, drinking and dancing were not the exception? Or to remember that Kuwait University was not segregated when it was first founded and was co-ed until 1996? Or that in 1957 the Council for Education introduced a short dress with red ribbons as the school uniform for girls in place of the by then contested abaya? What would it be like to remember that, until 1991, 380,000 Palestinians lived in Kuwait, with little inconvenience to Kuwait and much mutual benefit? That Saudi Arabia was as much a threat to Kuwait’s sovereignty as Iraq? In other words, what would it be like to remember experimentation and pushing boundaries rather than rigidity and burying our heads in the sand? At a time when so much outside the world of fiction seems to be screeching, emphatically, ‘No!’, it is fiction we can rely on – as I have for most of my life – to insist, stubbornly, despite everything, ‘Yes!’

Andy Warhol exhibited his work in Kuwait in 1976 (Sultan Gallery Archives).

In addition to alerting us to alternative versions of the past, present and future, fiction also reminds us that our point of view is not the only viable point of view out there. Our life is one among billions. Other people’s individual stories matter as much as our own, though in this time of socially networked self-promotion, this reality is too easily ignored. And while social networking and access to electronic data may give the impression of being hooked into difference and/or otherness, of having an immediate connection to the world at large, this immediacy may, in fact, produce the opposite effect. In 24/7, Jonathan Crary writes, ‘Part of the modernized world we inhabit is the ubiquitous visibility of useless violence and the human suffering it causes. This visibility, in all its mixed forms, is a glare that ought to thoroughly disturb any complacency, that ought to preclude the restful unmindfulness of sleep.’ The problem with our 24/7 access to images and information is that it does not, in fact, disturb our complacency. Never was this insight proved truer than in the summer of 2014. This is not to say that the images we view and articles we read online about individuals, nations and events, among other things, do not touch us; simply that the outcome of this scrutiny is not always (or even often) ethical practice. As Crary puts it, ‘The act of witnessing and its monotony can become a mere enduring of the night, of the disaster.’6

In contrast to the speed of digital time, the pace of fiction is slow. Fiction produces the conditions necessary for readers to inhabit different modes of life intimately because reading is a process that takes time. The attention and focus it requires produce this intimacy between reader and text. In one way or another, we, as readers, are invested in what we read or we wouldn’t do it. We come to care about the characters or the style or the place or whatever else in the book we happen to be reading. Fiction builds bridges between far-flung people and places and times in ways that might never be possible otherwise – certainly not through ever-shorter online articles, blogs, fluid news-feeds, 140-character Tweets, Instagram images and all the many other forms of digital detritus. Fiction, with its slower-paced (intransigent?) temporality, gives us the time we need to really explore difference – lives and experiences different from our own, times and places different from our own, beliefs and values different from our own. In so doing, it produces the conditions for an ethics of otherness. By inhabiting difference through fiction – slowly, closely – I would suggest we become less likely to want to attack, colonise, oppress or homogenise the unfamiliar, whether politically, economically, socially, culturally or militarily. When we read Ghassan Kanafani’s plangent short stories about Palestinian children, for example, the number of young civilian deaths in Gaza takes on an altogether different resonance. Instead of numbers and media abstractions, they become Kanafani’s children, singular lives and irreplaceable futures snuffed out.

On this understanding, reading or writing fiction is no idealist escape from reality, no utopian castle in the sky. Fiction becomes a constituting factor in the production of an ethics of otherness, a global ethics we could put to work towards a more equitable common future. This may seem a heavy task to place upon the shoulders of fiction, but in my estimation fiction’s shoulders are broad enough to take it. In the face of a world that seemingly shuts its ears to the lament of intolerable life, in the Middle East among other regions, fiction listens to and relays, among other things, our shared humanity.

Edward W. Said remained an unapologetic humanist to the end, albeit a refigured, post-Enlightenment humanist. For him, fiction was a humanising force whose power should not be underestimated. In Orientalism, he notes that Arabic literature was conspicuously absent from early Middle East Studies departments in the United States. This made it possible for experts to rely on ‘“facts,” of which a literary text is perhaps a disturber’.7 Literary texts disturb seemingly incontrovertible ‘facts’, rigidities of all sorts. Literary texts remind us of (or alert us to) alternatives to normative views and widespread perceptions. Bite-sized ‘facts’, digitally circulated at lightning speed, produce familiar dehumanising stereotypes, such as, ‘all Arabs are terrorists’ or ‘all Americans are infidels’. Literature – in its regular refusal to regurgitate such ‘facts’ as a matter of course – interrupts these counterproductive, dehumanising axioms. Never has this particular function of fiction been more urgent in relation to the Middle East than at this moment. Never has it been more urgent in the Middle East itself than now.