Ancient

Cultures and Lore

An ancient temple lies twelve bumpy miles from Highway 11 on the Big Island of Hawaii. Here, on this isolated spit of land known as Ka Lae, is Kalalela Heiau. The fishermen who still work these waters leave offerings to the Hawaiian deities on the lava stone structure.

Several years ago, the Kapiolani Rose Garden, near Diamond Head on the island of Oahu, was experiencing a rash of thefts. Tourists were stripping off the blooms and whole rose bushes were being spirited away. Charles Kenn, a renowned kahuna, was called in to protect them. The thefts stopped.

Many students of hula make pilgrimages to a temple set on the rocky Na Pali coast of Kauai. There they offer flower lei to Laka, the goddess of the hula.

On the edge of Halemaumau, the steaming sulfurous domain of the demigoddess Pele at Kilauea on Hawaii, numerous offering are left by Her worshippers. Leaf-wrapped volcanic rocks, scarlet berries of the ohelo (a close relative of the cranberry), incense, and other offerings are place there or thrown into the crater. During recent eruptions, such as those that consumed part of the Royal Gardens subdivision on Hawaii, homeowners who had invoked Pele reported that their houses had been spared the wrath of Her molten rock.

There are those who say that the Hawaiians have forgotten their old ways of worship and magic, that they no longer pray to Kane for rain, that they no longer see Hina in the Full Moon or Pele in the dancing fountains of fire. There are those who say the magic of Hawaii is long dead, buried under 150 years of Western dominance, religious conversion, and tons of concrete. First-time visitors arriving at Honolulu International Airport are apt to believe such statements. The long ride from the airport to Waikiki passes junkyards, heavy industrial areas, and shabby warehouses. The beach itself glitters with carefully groomed, imported sand, all but swallowed up by multimillion dollar hotels.

But above Honolulu, in the Tantalus Heights, lies Keaiwe Heiau. Now a state park, this ancient healing temple is still visited by the sick who leave offerings among its stones. An inscription on a plaque there reads:

A temple with life-giving powers believed to be a center where the Hawaiian Kahuna Lapa’au or herb doctor

practiced the art of healing. Herbs grown in nearby

gardens were compounded and prescribed with prayer.

—Commission of Historical Sites

Twenty or thirty minutes away at Wahiawa, in the center of the island, are pohaku (stones) with healing powers.

Most Hawaiians today are of “conventional” religious backgrounds. The missionaries, who first arrived in 1820 found the peoples ripe for the new religion. The Mormons made tremendous inroads. Their Polynesian Cultural Center, located in Laie on the island of Oahu, is the single most-visited attraction in the state.

Still, the earlier ways of existence on these islands—reverence for the earth, the sea, the sky, the water, and the plants—lives on. In 1984, a botanist told me that she prays to Ku for protection while hiking in the mountains. Time-honored deities are thanked prior to collecting flowers and foliage to create lei. Fishermen still attach ki leaves to their boats before setting out.

Many persons of Hawaiian ancestry still grow dracaena and ki plants outside their homes for money and protection, respectively. When ground is broken for new construction a kahuna is often called to bless the area with salt, water, and a ki leaf. The importance of this last ritual is affirmed by numerous stories of the accidents and strange occurrences at building sites at which it wasn’t performed—workmen are killed, the earth itself sinks, heavy pieces of earth-moving equipment are found turned on their sides in the morning.

The kahuna is probably the least-understood aspect of ancient Hawaii. Numerous books have been written about them. Most are contradictory and bear little resemblance to the truth. One recently published book seems to combine the reminiscences of a Pleasant Hawaiian Holidays tour, faulty research, and some psychic detective work.

The kahuna were and are the keepers of the secret. These men and women were experts in various fields. In today’s world, a persona with a PhD in psychology is a type of kahuna, as is a master sculptor, a skilled weather forecaster, a miraculously successful healer, an engineer, and a well-trained psychic.

There were kahuna who specialized in love magic, in navigation, in divination, in the construction of canoes and housing, in prayer. Far from the evil, scary creatures that the missionaries depicted them as, the kahuna were respected masters.

One of the best-known contemporary kahuna describes his field as philosophical, scientific, and magical practice. Kahuna aren’t merely magicians. Several recent books have described huna as a purely psychological system. These are based on the works of Max Freedom Long, a researcher who, through investigating the Hawaiian language, sought to crack what he considered to be the “huna code.” Unfortunately, Long never spoke to a kahuna, though they were around. His books—and those based on them—are sadly incomplete.

What is the heart of old Hawaii? It must lie in her people’s views of deity. All their rites of worship, their temples, their magical practices stem from this people’s relationships with the forces of nature.

Their deities, the personifications of the wind, the earth, volcanic activity, the fish, birds, and all the other features of their string of islands, were conceived of as being real, as real as those of any other religion and perhaps more so, since the earthly forms of their deities were all around them. No aspect of life was without religious impact. Fishermen prayed to Ku’ula for good catches; medicinal plants were gathered with prayers to Hina and Ku; all planting, harvesting, and eating were accompanied by prayers. Births and deaths, house building, sports of all kinds, even combat—all were overseen and nourished by the deities.

No one deity was revered above all others by all people at all times. Just as in ancient Egypt, certain gods and goddesses rose and fell in favor. Small geographic areas worshipped deities unknown to outsiders. The Hawaiians themselves describe, in the prayers that have been preserved, the 4,000, the 40,000, and 400,000 gods.

Pele is perhaps the most famous of them to outsiders, and yet, she wasn’t quite a goddess. The woman of flame, who lives in Kiluaea on the island of Hawaii, is the kupua, or demigoddess, who created the islands themselves through volcanic activity. Searching for a home for herself and her brothers and sisters, Pele dug pits for her fire that were free of groundwater. In turn, she created the islands from Ni’ihau to the Big Island of Hawaii, where she continues to live. On Kauai, two caves near Haena can still be seen. They represent earlier attempts of Pele’s search to find a home.

Pele has not been forgotten by the Hawaiian people. As mentioned above, she is still given many offerings, and stories of her appearing in fire, steam, and mist during eruptions are commonplace. She is also said to show herself as a beautiful young girl or an old, wrinkled woman. Many drivers have reported picking up a female who stood by the side of the road. Within moments, she disappears from the car seat. That is Pele.

Though Pele is the spirit of the volcanoes, she isn’t a wrathful being. Many see her as a true mother goddess, who continues to create new land when lava reaches the sea, stretching the size of the island of Hawaii. And unlike volcanic eruptions in most other parts of the world, those in Hawaii threaten little danger to human life.

There are many other Hawaiian deities:

Kane is seen in sunlight, fresh water, living creatures, and forests. Some myths credit him with creating the universe. Earthly forms of Kane include ko (sugar cane) as well as the beautiful ohia lehua, a tree bearing feathery red flowers.

Lono is the god of agriculture, fertility, the winds, gushing springs, and rain. He presides over many sports. At his heiau, people prayed for rain and rich crops, and offered plants and pigs to him. All Hawaiians ate from his food gourd. He is seen in the kukui tree, whose nuts were once made into lamps and are now fashioned into durable lei. Lono’s other early forms include the ’ualu (sweet potato) and the leaves of the kalo. From the root of the kalo (Tahitian: taro) poi is made.

Ku is the famous war-god of the ancient Hawaiians, the male generative power. It was at his temples that human sacrifices were made. Kuka ’ilimoku, one of the many forms of Ku, was made famous by Kamehamha I. A huge wooden statue of Kuka’ilimoku can be seen in the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. Other aspects of Ku (all the deities had many) include Ku’ula, the fisherman’s god. Earthly forms of Ku include the hawk.

Human sacrifice has to be mentioned in any account of the ancient Hawaiians. It is certainly savage to our eyes, but it played an important ceremonial role at certain times. There has been speculation that the practice was introduced to Hawaii from outside its islands. (Before shaking our heads in horror, let’s remember our own form of human sacrifice, one carried out on prisoners who are given death sentences. How different are we from the ancient Hawaiians?)

Hina is seen in the setting sun as well as in the moon. She rules over corals, spiny sea creatures, seaweeds, and cool forests. Women who beat tree bark into the cloth known as kapa (tapa elsewhere in the Pacific) prayed to Hina.

It may be surprising that Poliahu was revered by early Hawaiians, for she is a goddess of snow. However, Mouna Kea, on of the great volcanoes that make up the Big Island of Hawaii, is often shrouded with snow. It is the home of Poliahu, the beautiful goddess.

Laka oversaw the hula, which was originally both a sacred dance performed for the deities and the ali’i (chiefs) as well as a secular activity for the common people. Laka is represented on the hula altars by a block of wood wrapped with kappa cloth. Several plants, especially ferns, are sacred to her.

There are many other deities and demigods, such as Maui, the Hawaiian trickster who, among other exploits, fished up the islands from the bottom of the sea with his fishhook. Maui’s magical hook can still be seen hanging in the skies over Hawaii, made up of stars. Kamapua’a, a demigod who appeared in various forms including that of a pig, had a tempestuous love affair with Pele. The mythology (sacred literature) of Hawaii is filled with passion, adventure, love, and magic. It is required reading for anyone wishing to pierce into ancient Hawaiian consciousness.

As we’ve seen, the ways of the past still live in Hawaii. It was recently proposed to tap a stream from Kilauea Crater in order to produce geothermal energy. Modern-day priestesses of Pele immediately protested, stating that she still lives in all parts of the crater and that the plan would be nothing more than selling part of her body. To their great dissatisfaction, the priestesses lost and the plans proceeded. Money overcame the old ways, as it often has.

Is there still magic to be found in Hawaii? Yes. It’s there in the ground. In the air. In the cries of birds. In the rustling of plants. In the splash of water tumbling down a volcanic cliff. In the sunrise from Halakala. In the green, white, and black sand beaches. In the thundering waves.

Mana—the Hawaiian concept of the natural energy that resides in all things—permeates the very rock upon which these islands formed. The life-force is so vibrant here that the sensitive can feel it on the breeze when stepping off a 747 at the airport.

Yes, the magic of Hawaii lives in its people and the land itself. It is there, waiting, ready to reveal its secrets to anyone who goes with an open heart and open mind.

And it is alive!

Recommended Reading

Beckwith, Martha. Hawaiian Mythology. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. 1979.

Cox, J. Halley, and Edward Stasack. Hawaiian Petroglyphs. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1970.

Malo, David. Hawaiian Antiquities. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1971.

McDonald, Marie. Ka Lei: The Leis of Hawaii. Honolulu: Topgallant/Press Pacifica, 1985.

Mitchell, Donald D. Kilolani. Resource Units in Hawaiian Culture. Honolulu: The Kamehameha Schools Press/Bernice P. Bishop Estate, 1982.

Stone, Margaret. Supernatural Hawaii. Honolulu: Aloha Graphics and Sales, 1979.

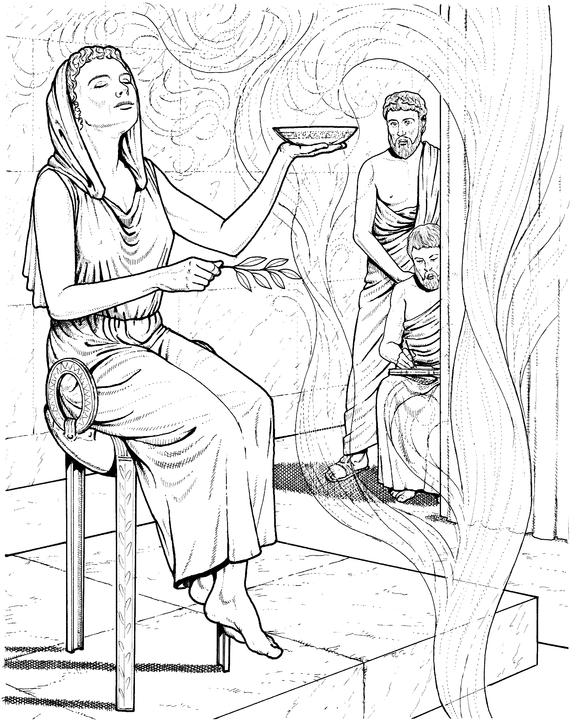

Though there were three great oracles in ancient Greece—Trophonius, Dodona, and Delphi—it is the latter of these which is best remembered today.

The heart of these sacred places of prediction was the Pythia, the priestess who made the mystic pronouncements. In the earliest times, the Pythia was chosen according to her youth, beauty, and noble background. Once a Pythia had been seduced and swept away by a handsome Thessalian, however, some changes were put into effect.

Thereafter, the Pythia was a woman of about fifty years of age from an obscure family background. Because of her ignoble birth, she was usually uneducated. However young or old she might be, the Pythia remained celibate for the length of her duties.

Before making oracular statements at Delphi, the Pythia was purified in a stream, robed, and crowned with laurel leaves (bay). Her priests escorted her into the Adyton, the underground chamber of the oracle at Delphi. There she was seated on a tripod beside a river that flowed through the subterranean chamber.

She probably inhaled the sulfurous fumes rising from cracks in the cavern’s floor and further prepared herself by chewing bay leaves (thought to have a hallucinogenic effect). Bay leaves were also fumed in the cave.

Outside the Adyton, the client who came to seek knowledge made offerings of ritual cakes, gold treasures, and artwork (which supported the temple), and sacrificed a sheep or goat on the hearth. Once this had been done, he was escorted by the temple’s priests into the sanctuary—far removed from the Pythia so that their presence didn’t disturb her.

The question was put to the Pythia. She then entered an ecstatic state: chest heaving, eyes flashing, she tore her hair and violently trembled. Then, finally, she uttered a few words, which were duly recorded by her attendant priests.

These priests were of the utmost importance, for the Pythia’s prophecies were usually couched in such obscure terms that an interpretation was necessary. Once the priest had written down the prophecy and handed it to the inquirer, the process was complete.

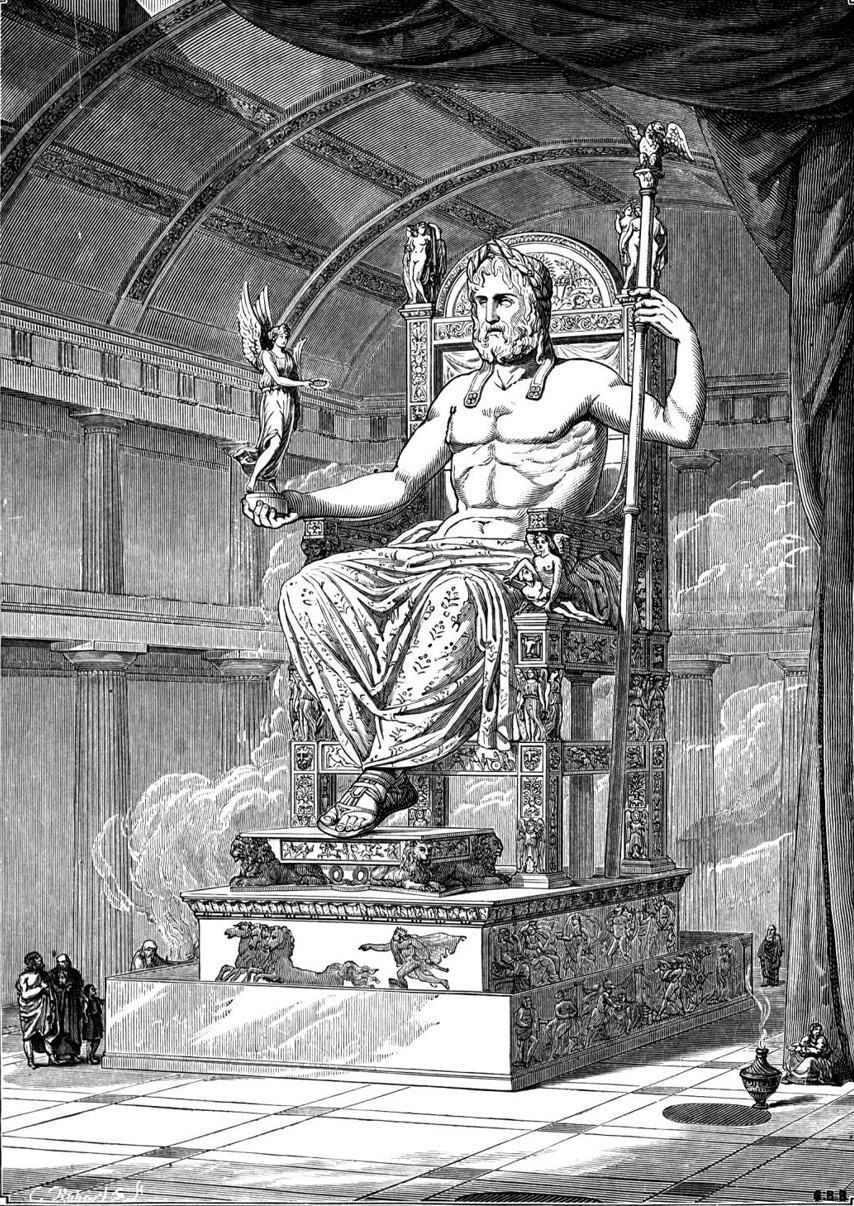

For over a thousand years, the Oracle at Delphi fulfilled the needs of tens of thousands of persons eager for a glimpse into the future. In its earliest days, the Pythia appeared no more than once a year. Kings and the wealthy upper class had to wait for this annual event, held on the seventh day of Bysios (roughly corresponding to our February-March).

Soon, however, demand grew so great that the oracles were opened once a month. Two or even three Pythia would be stationed at each shrine, and still the crush of need would overwhelm them.

Though only the richest could consult these mystic women, mass oracles were also held each year. According to old records, the Pythia simply sat on the steps leading to the temple and, in broad daylight, answered questions proffered by the populace.

Curiously, women (save for the Pythia) weren’t allowed within the temple to consult the oracle. They were forced to send male friends to ask.

Not surprisingly, the bulk of the prophecies proved themselves to be true, though the inquirer often misinterpreted the priest’s translations.

The philosopher Cicero, who was a famous skeptic, stated, “Never could the oracle of Delphi have been so overwhelmed with so many important offerings from monarchs and nations if all the ages had not proved the truth of its oracles.”

Though Delphi was justifiably famous, the other two oracles were more obscure. That at Dodona consisted of a shrine near a sacred oak forest. The Pythia simply went to the prophetic oak on a riverbank, stood beneath it, and listened to the sound of the moving leaves or the stream (which sprang from a nearby spring). Each sound possessed a separate, distinct meaning (recorded in a book), which led to the inquirer’s answer.

The third oracle, known as Trophonius after the architect of that at Delphi, was physically similar to its more famous sister, but consulting it was a terrifying experience. At night, the querent climbed down a ladder, wriggled feet-first through a long, narrow tunnel, and then sat on some type of device that swiftly carried him deeper and deeper into the earth.

Throughout this demanding process, he was forced to carry a honey cake in each hand—failure to do so resulted in death. If he survived this, he was allowed to hear the Pythia’s words.

The oracles of ancient Greece were important social and political centers, and the phenomenon of world leaders consulting psychics hasn’t yet ended.

Sneezing has long been one of the most mysterious of our involuntary actions. The fact that sneezes usually occur without warning, and can rarely be stifled, led to their use as an oracle of the future.

From the classical period to the Middle Ages, sneezes were considered omens. To sneeze to the left (i.e., to feel it emanating from that side) was a sign of misfortune. To the right, a positive omen. To sneeze early in the day was favorable; to do so later or at night, unfavorable.

Additionally, a sneeze could also be an automatic exorcism, marking the withdrawal of an evil spirit, who might then wreak havoc on others near the sneezer. To halt any such problems, Greeks said “Zeus help us!” when one of their number sneezed.

Sneezing provokes the giving of similar good wishes in all parts of the world. These often call upon deities or health to avert the possible danger. Germans may say “Gesundheit” (“Health!”). Some English-speaking peoples invoke their concept of God to “bless” the sneezer, while the ancient Hawaiians stated “Kihe, a Mauliola.” (“Sneeze, and may you have a long life.”) Connections between sneezing and deity are common and ancient Aristotle wrote that “We consider sneezing as something divine.”

Among the fortunate days upon which to sneeze are New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. Sneezing then is believed to provide great fortune to the sneezer during the following year.

Hecate is perhaps the most famous of the Greek deities associated with magic. According to tradition, she was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, or Perses and Asteria, or Zeus and Hera. Though her pedigree is unclear, it seems certain that Hecate was a Titan of Thracian origin.

From the earliest times she ruled the Moon, the Earth, and the sea. Among her blessings were wealth, victory, wisdom, and successful sailing and hunting, but she withheld these from those mortals who didn’t deserve them.

She was the sole Titan who retained such powers under the iron rule of Zeus, and was honored by all the immortal deities. She even participated in the war with the Gigantes (giants). In time, her power grew so that she was associated with many other goddesses: as queen of nature, she was identified with Demeter, Rhea, and Cybele; as a huntress, protectress of youth, and moon goddess, with Artemis.

Later in Greek history, it was stated that Hecate was the sole deity (aside from Helios) who observed the abduction of Persephone. She left her cave and, torch in hand, assisted Demeter in her search.

Once Persephone had been found, Hecate remained with Persephone as her companion. This gave Hecate formidable powers over the underworld, and she became a goddess of purification and protection, accompanied by her dogs.

Hecate is best remembered today as a dark goddess, who at night sent out demons and phantoms; who taught magic and sorcery to brave mortals; who wandered with the souls of the dead after dark. Her approach was always heralded by the cries and howls of dogs. Despite this, she was also invoked for protection and was greatly loved.

Her home is alternately described as a cave, among tombs, near crossroads or within sight of a place where blood has been spilled during a murder. Images of Hecate are sometimes of a normal woman, but others represent her as possessing three heads.

Her worship was widespread, especially in Samothrace, Aegina, Argos, and in Athens, where she was honored in a sanctuary near the acropolis. In Athens, many homes displayed small statues of Hecate, which were either inside or outside the home. Such images were also placed at crossroads, and there is speculation that these Hecataea (images of Hecate) were consulted as oracles. At the end of each month, her worshipers set out dishes of food for her at a crossroads (where two roads crossed each other.) Honey and black female lambs were among her sacrifices. Hecate, then, is a complex goddess: giver of wealth and fortune, and mistress of sorcery. Even as late as the early 1600s, Shakespeare included Hecate in Macbeth, and she is still worshiped today by those unafraid of her awesome powers.

Birds have long been viewed as messengers of goddesses and gods. Their quickness, obvious intelligence, and often beautiful forms, coupled with their ability to fly, led to their intimate connection with deity throughout the world.

Birds in general have often been considered to be messengers of the deities. Many cultures linked them with the human soul, and the common English expression, “a little bird told me,” stems from ancient beliefs that birds could communicate with humans and pass on important information.

A few of the birds that have been associated with deities are listed here:

Apollo (Greek god of the arts, healing, and light): Raven, crow, hawk, swan

Athena (Greek goddess of wisdom, learning, and war): Crow, owl

Brahma (Hindu creator god): Goose

Eros (Greek god of love): Goose

Hera (Greek goddess of childbirth, home, and marriage): Crow, goose

Horus (Egyptian Sun god): Hawk, eagle

Ishtar (Babylonian goddess of love and fertility): Dove

Isis (Egyptian goddess of all things): Goose

Juno (Roman goddess of marriage, home, and childbirth): Goose, peacock

Jupiter (Roman supreme deity): Eagle

Kami (Hindu god of love): Sparrow

Kane (Hawaiian god of fresh water, sunlight, winds, and procreation): Owl

Ku (Hawaiian god of fishing, war, and sorcery): Hawk

Lilith (Mesopotamian goddess of night, evil, and death): Owl

Ma (Egyptian mother goddess): Vulture

Maat (Egyptian goddess of truth): Ostrich

Minerva (Roman goddess of wisdom): Owl

Nekhbet (Egyptian mother goddess; goddess of the underworld): Vulture

Osiris (Egyptian god of the dead, resurrection, and agriculture): Heron

Peitho (Greek goddess of winning speech): Goose

Priapus (Roman god of fertility): Goose

Ra (Egyptian Sun god): Hawk, goose

Thoth (Egyptian god of learning, writing): Ibis

The Valkyries (Norse goddesses who selected those who would die in battle): Raven

Venus (Roman goddess of love): Dove, goose, swallow

Yama (Hindu god of the dead): Owl, pigeon

Zeus (Supreme deity of ancient Greece): Eagle, swan, pigeon

The multicolored arcs that appear in the sky after or during a rain have long captured the imagination. Rainbows are, by their nature, intangible and fleeting things, possessed of magic and mystery. They’ve played an important role in shaping our mystic consciousnesses and have been closely associated with religion for thousands of years.

The most famous deity of the rainbow is Iris, the gentle great goddess of peace. Her name means either “the messenger” or “I join,” both of which suggest that Iris is the conciliator or the messenger of the deities, who restores peace to nature (much as a rainbow usually indicates the end of a storm).

Iris was the daughter of Electra and sister to the Harpies. She was one of the divine messengers who carried news from Mount Ida to Mount Olympus from deities to deities, and from deities to humans. She was primarily engaged in service by Hera and Zeus, but even Achilles once asked her to help him call the winds. Iris didn’t only respond to divine command, however, for she also offered assistance on her own initiative.

She was intimately connected with the rainbow. It was the only road on which she traveled. Thus it appeared at her command and vanished when no longer needed. In very early Greek religion, the rainbow was seen as the “swift messenger” of the deities, even before it became particularly associated with Iris.

No statues of Iris have been preserved. Still, frequent representations of her on vases—and in bas-relief reveal her form.

She’s often shown as a beautiful woman, usually dressed in a long, wide tunic covered with a lighter garment. A pair of wings sprouts from her shoulders, and she carries a herald’s staff in her left hand. A rainbow arches above her.

Some representations depict her as flying, with wings outstretched from both her shoulders and her sandals. While flying she carries the staff as well as a pitcher.

Little is known about her worship today. It seems to have been centered on the Island of Delos, where her worshipers offered her cakes made from wheat, honey, and dried figs.

The Delians apparently greatly appreciated the help of Iris. Upon one occasion, Leto, who was in labor on Delos, was delayed nine days from giving birth (to Apollo and Artemis) by Hera. The Delians promised Iris a necklace of gold and electron nine cubits long if she would come to Delos to assist with the birth. She did, and all went well.

Though little is known about Iris today, her symbol still shines in the skies above Greece after storms, and she may yet walk the multicolored stairway to Mount Olympus, to report on the activities that occur far below.

Whatso’er thy heart desire

Write it well in words of fire.

Cut the sacred apple through

Place the wish between the two.

Seal with twigs of lady’s tree

Place in kiln till dried it be.

Sleep upon it night or day

Till good fortune comes your way.

Few other cultures have valued scent as greatly as did the ancient Egyptians. They rubbed their bodies and hair with scented oils, bathed in perfumed water, inhaled the aromas of flowers during banquets, and placed cones of scented wax on their heads so that the aroma would be released as the wax melted down onto their wigs. Even food was perfumed, and banquets frequently took place in rooms strewn with rose petals.

Incense was also widely used in Egyptian religion and magic. The most famous of Egyptian incense materials, frankincense, was but one of the both delightful and strange ingredients burned in vessels of fire.

Many ancient Egyptian incenses can’t be made today, for some contain unidentifiable ingredients. Still, a few clear formulae have been preserved.

An all-purpose divinatory incense was made from frankincense, wax, storax, turpentine, and datestones. These were ground together with wine, formed into a ball, and placed on the fire.

To make spirits quickly gather to answer questions during divination, burn stalks of the herb anise and crocodile egg shells.

Other simple formulae include: crocodile bile and myrrh, burned to “bring the gods in by force” and crocus and alum, which were censed to “bring in a thief.”

Ancient Egyptian

Spell to Cure a Dog Bite

Little is known today of folk magic in ancient Egypt. Though we have records of state rituals, not much was recorded regarding the simple magic of the common people.

One of the few sources of such workings is contained in what is today known as the Leiden Papyrus. This papyrus was collected in Thebes in the early 1800s and was probably written about 300 ce. Though it is of a late date, it bears little Greek and/or Christian influence.

The unnamed scribe who created this 16-foot papyrus didn’t write the rituals; he simply copied them from other papyri. Thus, it seems clear that much of the information dates from 100 to 200 years earlier than its compilation, still within the Greek period of Egypt but closer to the purer Egyptian culture.

The papyrus is a motley collection of spells. Several sections outline methods of divination, usually involving a “pure boy” (who is ritually prepared to see the spirits). Other sections include erotic recipes, cures for a variety of ailments, a few spells “to create madness” and the like. One of these spells runs thus:

Spell Spoken

To the Bite of the Dog

“I have come forth from Arkhah, my mouth being full of blood of a black dog. I spit it out, the … of a dog. O this dog, who is among the ten dogs which belong to Anubis, the son of his body, extract your venom, remove your saliva from me again. If you do not extract your venom and remove your saliva, I will take you up to the court of the temple of Osiris, my watchtower. I will do for you the parapage of birds, like the voice of Isis, the sorceress, the mistress of sorcery, who bewitches everything and is not bewitched in her name of Isis the sorceress.”

And you pound garlic with kmou [unidentified plant] and you put it on the wound of the bite of the dog, and you address it daily until it is well.

Humans have invented many ingenious methods of peering into the future. Coffee grounds and crystal spheres, tarot cards and pendulums, observation of the movements of animals, the shapes of clouds, and the ripples of water are but a few of these techniques.

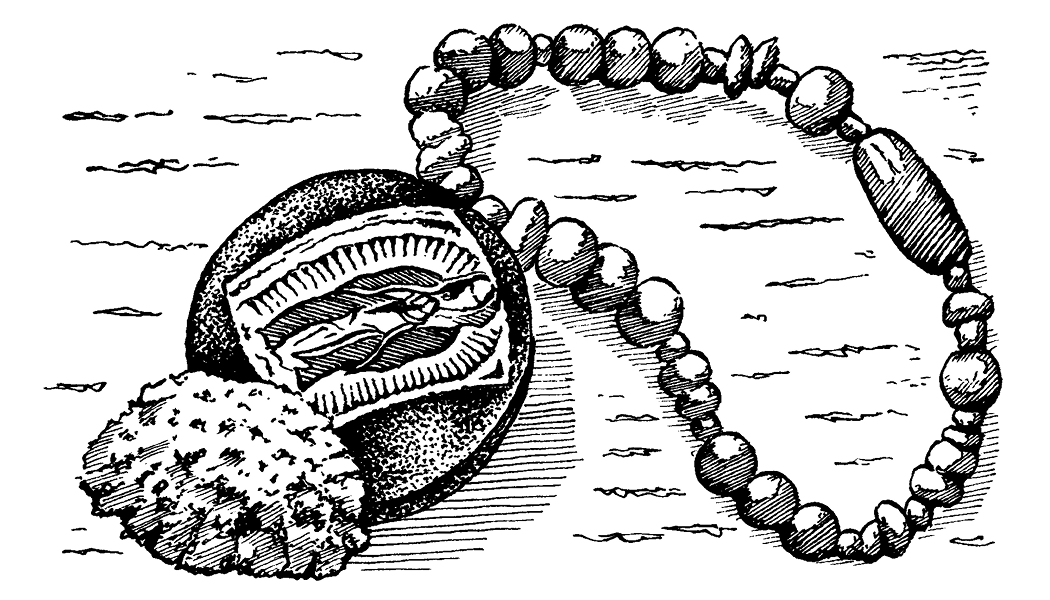

A lesser-known divination, of uncertain heritage, requires simple tools: a sieve (or colander), seven small bivalve (clam) shells, one black bean, and one white bean.

To use the oracle, place all items into the sieve. Shake it seven times, from the left to the right. Stop and look for these things:

- The position of the shells relative to the beans

- The number of shells that have landed upright (i.e., with the dome-shaped surface facing up) or upside down (the hollow portion facing up)

Here are some of the prophecies that can be seen:

- 4 to 7 shells, hollow side up, near the white bean: luck, success, long life, fulfilling relationship

- 4 to 7 shells, dome side up, near the white bean: accident or illness

- 4 to 7 shells, hollow side up, near the black bean: a period of luck interrupted by tribulations

- 4 to 7 shells, dome side up, near the black bean: problems with money or business

- 4 shells, hollow side up, forming a circle near the white bean: a legacy; a windfall

- 4 shells, hollow side up, forming a circle near the black bean: sadness

- 3 shells, dome side up, forming a triangle near the white bean: wishes will come to fruition

- 3 shells, hollow side up, forming a triangle near the black bean: concentrate on the present

- Any number of shells, either side up, forming a cross near the white bean: sadness

- Any number of shells, either side up, forming a crescent: luck and blessings

- All shells, dome side up: strength

- All shells, hollow side up: love and peace

Note: All such tools of divination can be effective only if they contact the psychic mind. Otherwise, they’re but toys. If this form doesn’t speak to you, search for another. Many have found their perfect divinatory tool in the tarot, others in the pendulum, rune stones, and the I Ching.

The tool isn’t as important as the effect that it has upon you, so carefully choose it.

On the night of the Full Moon when the shimmering globe rises slowly from the eastern horizon, look into its face. The dark areas of the Moon’s surface contain an image. What is this figure?

Persons in China, Japan, Tibet, India, Mexico, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere see a rabbit. Many stories are still told of how a rabbit hopped to the Moon and took up residence on its cold surface.

In Hawaii and throughout Polynesia, the Moon is thought to be inhabited not by a rabbit (an unknown creature), but by a Goddess, Hina. In Hawaii, Hinaikamala (Hina of the Moon) had grown tired of constantly making bark cloth, so she took her ipu (gourd container) and climbed “by the rainbow path” up to the Sun. Finding her new home to be too hot, she went instead to the Moon and can still be seen on its face with her gourd by her side.

The Moon is usually linked with lunar animals (such as rabbits and hares) and with women or goddesses (Hina). Thus, when children today gaze up, trying to see the “man in the Moon” they’re often disappointed, for no “man” is visible.

Memories of the hare or woman in the Moon may have been forgotten as the new faith overwhelmed earlier Western pagan religions. Seeing a woman or hare in the Moon wasn’t favored by those of the new religion, due to their connections with Moon-worship and totemism.

What to do? The story of the “man in the Moon” was invented and neatly filled the bill.

But elsewhere, far removed from the effects of this new religion, a rabbit with floppy ears and tail or a woman sitting beside her gourd, are still seen on clear evenings on the Moon’s glowing face.

The man in the Moon isn’t.

Moon Spells

Upon seeing the Full Moon, form a circle with the thumb and first finger of your talented hand. Hold it up until the Moon rests within this ring, and say these words in a hushed voice:

Good moon, round moon,

Full moon near:

Let the future

Now appear.

Gaze at the Moon and ask a question; it shall be answered.

Under the dim light of the waning Moon, write on a piece of paper that from which you wish to be freed. Tear the paper in half three times and bury it. Then say:

Pray to the moon when she be slivered

From ill you shall be delivered.

All that has harmed me now is bound:

Down, down beneath the ground.

Take a piece of silver (jewelry or a coin), a cup, and a pitcher of water out under the light of the Moon. Pour the water into the cup. Place the silver into the cup. Stir the water thrice clockwise with a finger. Holding the cup, walk thrice in a clockwise circle beneath the Moon while saying these words:

O moon light

Wrap me tight

Guard me now

Day and night.

Drink the water, then retrieve the coin or jewelry. Wear or carry the silver for one lunar month for protection. Repeat if needed on the next Full Moon.

To create prophetic dreams, walk outside with a fresh white rose. Hold it up to the Moon between both hands so that the blossom is flooded with Moonlight. Say:

Awaken my second sight

Press the white rose against your forehead, saying:

By the power of this rite

Place the flower under your pillow before sleep and remember your dreams.

Scrape the rind from a ripe lemon. Allow to dry for seven nights on a ceramic plate. On the seventh night, take the plate, a small square piece of white cloth, and a threaded needle outside. By the light of the Moon, transfer the dried lemon peel to the center of the cloth. Fold the cloth in half, creating a triangle. Quickly stitch together the two open sides with the threaded needle. When you’ve finished your work, hold it up to the Moon and say:

The charm is made!

Place it under your pillow for restful sleep at night.

Contemporary Mexican folk magic is the result of a complex mixing of cultures bearing clear signs of Aztec, Roman Catholic, European, and even Buddhist influences.

In nearly every town in this predominantly Catholic country, charms can be secured from herbalists, street vendors, and at open-air markets. Since charms are concrete representatives of underlying beliefs, we’ll first examine a few of these.

The Piedra iman (lodestone) is a common magical tool. Unlike those sold in the United States, they’re rarely painted but are usually covered with clinging iron filings. Such natural magnets are carried, worn, or hung in homes and businesses to attract love or for protective purposes. In some villages, they’re washed every Tuesday and Friday with wine.

Piedra iman are sometimes packed with wheat and sewn into red cloth. On this cloth is a picture of San Martin de Caballero (Saint Martin the Horseman). Such charms are made to guard against hunger and to instill protection. (A Mexican magician also taught me to place a Piedra iman in a triangle for positive vibrations.)

The Ojo de Venado (“deer’s eye”) is a charm given to children for protection. It consists of a large, flat, nut-brown seed with a circular band of black. A red string is usually threaded through the seed. Attached to the thread may be a tassel of red thread, beads, or a small section of a magical wood.

A household charm is known as Coronita Ajo. This is a small wreath made of separate cloves of garlic strung onto a wire and entwined with red ribbon. It is hung in the home (or business) for good luck and to guard against evil.

Perhaps the most famous—and grisly—of all Mexican charms is the chuparosa (hummingbird). This consists of a small, dried hummingbird wrapped with red cloth. This relic is used in love-attracting rituals.

Yet another protective charm is known as the herradura

(horseshoe). These are small horseshoe-shaped magnets wrapped in red ribbon, packaged in cellophane along with a saint’s picture and small packets of herbs. At times, a small representation of Buddha may also be included with the herradura. These charms are used in businesses to drive away evil and to invite prosperity and customers.

Siete Machos is the name of a cologne manufactured in Mexico. Its strong scent has led to its use in numerous healing and anti-bewitchment rites. (The bottle’s label shows smoke rising from a censer, surrounded by seven goat’s heads.)

Other uses include mixing Siete Machos with Florida water (a cologne). This is splashed on the body every fifteen days for internal purification.

These few examples clearly show the multicultural nature of many contemporary Mexican charms. The hummingbird was sacred to the ancient Aztecs. The saints are often seen as Catholic versions of pre-Christian deities, and are utilized in decidedly non-Christian ways.

Garlic was imported from Europe by the conquistadors. Images of the Buddha, which are frequent in charms, could only have been late introductions.

Mexican folk spells are far more difficult to uncover, for such actions are secret and are usually performed in privacy. Here are a few, and they differ little from those of Europe. All of these involve love.

For marriage, a handful of basil is impregnated with the magician’s favorite perfume or cologne. This mixture is then buried in a flowerpot.

A love perfume is created by collecting seven roses on a Friday after sunset. The petals of these roses are mixed with one liter of water and seven drops of the practitioner’s favorite perfume or cologne. The magician is directed to bathe normally that evening but to rinse with the mixture. This rite is repeated for seven consecutive Fridays.

It must be noted that the use of such charms and spells usually isn’t regarded as magic (which is universally believed to involve devil-worship, another Spanish influence), but as religion. The predominance of the saints in many magical charms suggests that many of these persons are performing religious magic in a broadly Catholic way.

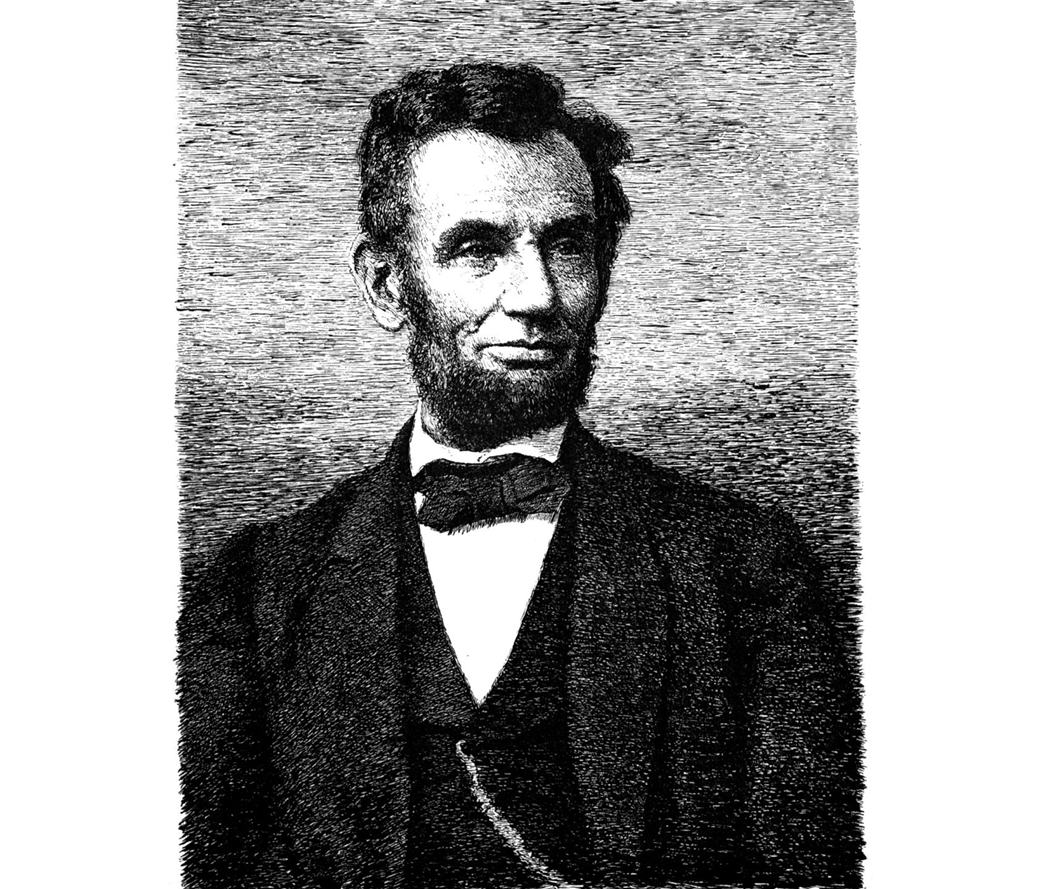

Many tales are told today concerning our sixteenth president. It is widely known that, during his lifetime, Lincoln was interested in spiritualism, astrology, and other arcane matters. He is said to have even held seances in the White House. What is little known, however, was his apparent belief in the powers of a well-known herbal charm: the four-leaf clover.

Four-leaf clovers are popular magical talismans carried for a variety of purposes: to draw luck generally; to attract money, health and wisdom; to promote love. Among the more sinister of the traditional powers of four-leaf clovers is that its bearer is able to detect the presence of evil spirits.

Precisely why Lincoln carried a four-leaf clover (if he did; this is still subject to debate) is unclear at this late date, but his alleged charm did manage to create more recent history.

In the 1920s, international tennis champion William T. Tilden II was about to face Gerald Patterson at Wimbledon. The day before the first match, a friend presented Tilden with Lincoln’s clover for luck. He soon defeated Patterson and, in fact, won every match until the magic sprig was misplaced. Fortunately, the clover reappeared just before he won back the American tennis title in 1929.

The “king of nets” placed great faith in this little relic of a past era. Lincoln’s thoughts regarding this four-leaf clover are unknown, but it’s refreshing to know that at least one American president may have relied upon the powers of herb magic.

It seems clear that Lincoln didn’t have his four-leaf clover with him when he went to Ford’s Theatre on April 15, 1865—the day of his assassination.

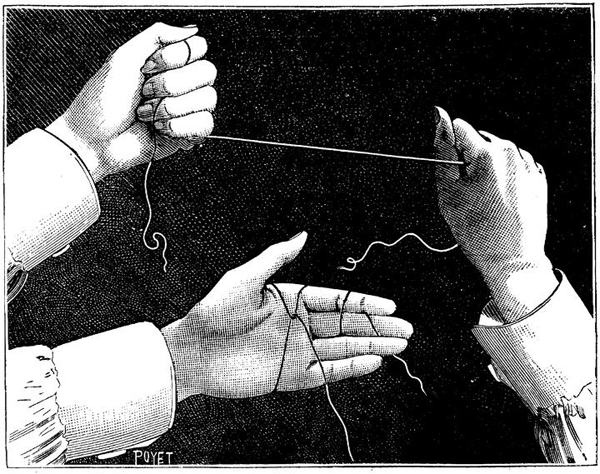

When I was very young, my family sponsored an exchange student from Iran. After telling me exotic stories of his homeland (our countries were then on friendly terms), the young man taught me how to make several string figures that he’d learned as a boy.

Stunned at the prospects of creating intricate patterns with

something as simple as a piece of string, I soon grilled my friends and learned how to create a few other string figures. One of the mysteries that I learned was that, if two persons correctly played cat’s cradle for a very long time, the strings would automatically make a rare and unusual pattern. I could never play long enough to discover if this was true.

Even at the age of ten, I was a researcher, and soon read a book on the subject. I became fascinated by string figures.

Little did I know that persons around the world had created similar figures; that many of them were made for religious or magical purposes, and that in most cultures everyone, from the youngest children to the elders, made string figures.

Among the areas where string figures were made are Alaska, Canada, the continental United States (the Apache, Tewa, Zuni, Pawnee, Navajo, Omaha, and Cherokee are among the peoples who made them), Peru, Paraguay, Hawaii, Guyana, Angola, Botswana, and South Africa.

The Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, Melanesia, Fiji, the Society Islands (including Tahiti), Tikopia, New Caledonia, the Gilbert Islands, Japan, Korea, China, Denmark, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, France, and the Netherlands were other places where string figures were made.

Ethnologists began recording string figures and their methods of construction in the late 1800s. Unfortunately, they often failed to similarly record the mythic or magical history that accompanied the creation of these figures, so our information is limited.

On the Gilbert Islands (in Melanesia), Ububwe was the god of the string figures. After death, the human soul was carefully questioned by Ububwe regarding its knowledge of string figures before it was allowed to enter the underworld.

In Alaska, the string was seen to possess magical power when properly used. Ritual string figures were made during winter to snare the Sun and prevent its departure. Additionally, boys of this area were forbidden to play cat’s cradle, as this might result in their hands becoming entangled in the harpoon line later on in life.

In many lands, string figures were made to represent deities. Certain words chanted over the figure reinforced its association with the deity, and creating the string figures may well have been a form of ritual invocation.

So magic can be found in the most curious of places, even in the games that many of us learned in our youth. Much has been lost, but the most famous form, cat’s cradle, is known in Germany to this day as hexenspiel: witch’s game.

Cat’s Eye

There is an old saying that if you fear nightly intrusion by ghosts or evil spirits, you should hang a piece of knotted string from your door handle before you lie down to sleep.

Your unwanted visitor will have to untie every single knot before it may enter the room—and with any luck the sun will be up by then!

Throughout the world, water has been rightly regarded as a sustainer of life. From this observation it was but a small step to acknowledge bodies of water fresh and salt—as the dwelling places of spirits and deities.

Rivers (such as the Ganges, the Nile, and the Euphrates) have long been worshiped as manifestations of deity. In England, the river Severn was the goddess Sabrina, to whom flower offerings were thrown at regular intervals.

Many peoples of North America similarly made offerings of beads and tobacco to river spirits. Such rites honoring water spirits are also known from Africa, Sri Lanka, Korea, Mexico, France, Germany, and throughout Europe.

The oceans have long been honored in the persons of Tiamat, Kanaloa, Poseidon, Llyr, and Neptune, among other deities. But wells, both natural (springs) or artificially created, have garnered more than their share of worship and magical observances in Britain and Europe.

The charming custom of well-dressing still continues in some parts of Britain. This ancient practice, in which specific wells are decorated with flowers, is now associated with various saints and is conducted with due religious ceremony. However, it stems from the most antique days, long before the introduction of Christianity.

As early as the sixth century ce, Gildas wrote of Britons paying homage to wells and rivers. From the sixth to the twelfth century, various English kings and religious leaders passed laws forbidding well-worship. Fortunately, their efforts were in vain, and over 100 wells are recorded as having received honors.

With the growing acceptance of Christianity throughout Britain, the conversion of the wells began. Those that had once been sacred to Celtic or Teutonic goddesses were transferred to the saints or even to Mary herself.

But the magic continued. Many wells possessed healing waters, and some, such as that at Buxton, became quite famous. Even Queen Mary visited this well on numerous occasions, and wrote of the “incredible” nature of the water’s cure. By this time, the well had been rededicated to St. Anne.

There were many types of magic wells in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland: holy wells, rag wells, wishing wells, pin wells, and even cursing wells.

Holy wells were those associated with goddesses, such as the famous Chalice Well at Glastonbury. Virtually all wells were once considered to be “holy,” as water is a divine substance.

Rag wells are places of healing where the supplicants tied small bits of cloth onto nearby bushes and trees as an offering to the spirit or deity of the well.

Wishing wells are quite familiar. A coin was thrown into the well with a “wish.” The wisher then noted the number of bubbles that arose and their size and, from these signs, determined whether the wish would be granted. (The object tossed into the well constituted payment to the well’s spirit.)

Pin wells were similar. Pins (or buttons) were tossed into the well, and once again their movements indicated whether the wisher would be granted her or his wish. Additionally, bent pins were thrown into such wells for luck and as a protection against evil magic.

Cursing wells were much rarer. These were usually lonely places where it was believed that the well’s attendant spirit or deity would send curses to one’s enemies. Oval or circular stones were sometimes turned before such wells, and the curser walked widdershins (counterclockwise) around the well.

The rarest of all are the laughing wells. The waters of such springs usually possess natural carbonation, so that when small, heavy objects are thrown into them, a frenzy of bubbles is released. Little magical information regarding them has been

recorded.

At all but the cursing wells, the supplicant walked thrice clockwise around the well before praying or wishing; only then was the water drunk or the offering made.

Many spells have been created using well water, but most have been curative. Pliny (ad 77) writes: “Mix water in equal proportions from three different wells, and, after making a libation with parts of it in a new earthen vessel, administer the rest to patients suffering from fever.” The water from three wells would understandably be considered to be even more potent than that collected from just one source.

Divinations were also made with well water. In Scotland, the water from St. Andrew’s Well was poured in a wooden bowl and placed beside a patient. A small ceramic dish was gently laid on the surface of the water. If, while floating, it slowly rotated clockwise, the patient would recover. If counterclockwise, no recovery was in sight.

Many wells, lakes, fountains, and decorative pools to this day are littered with coins tossed by those who may well be unaware of the pagan origins of such practices.

Acknowledgments

I would like to gratefully thank Marilee Bigelow for her friendship and editorial comments. Marilee was one of Scott’s best friends, often sharing her recipes with him as well as accompanying him on several adventures to Hawaii. I have no doubt that her friendship helped Scott become a better person. I know her friendship has done that for me.

Enormous thanks also go to Holly Allender Kraig for her excellent editorial suggestions.

Another thanks goes to Bill Krause for his guidance and for backing this project. His positive attitude about my work was responsible for this book. I am very pleased with the result, and it’s due to Bill’s encouragement.

And finally, I have to acknowledge Scott Cunningham. His life touched so many of us, his magic changed the world, and his friendship changed my life forever.