Stock Market Set to Explode

October was awakened the next morning by a sharp stabbing poke in her thigh. Of all the ways to be awoken, this is one of the worst ones. I speak from experience. She rubbed at her crusted-over eyes and noticed it was still very early — barely even six. Her alarm wasn’t set to go off for another hour or so. Shuffling off her covers, October stood up and found a crisp envelope in her pyjama pants. “Living Girl” was scrawled across the front, and October realized, with a start, that one of the dead kids must have stuffed it into her pocket overnight. It was sort of her fault since she asked them to leave her a note, but this was getting a bit personal, she felt. Would you want Kirby LaFlamme stuffing things in your pockets as you slept? Doubtful.

She also realized the dead kids probably didn’t own any stationery. They must have stolen it from Mrs. Tischmann. Normally, she was against petty larceny, but if Tischmann was involved with Mr. O’Shea’s death, October hoped they took all her stationery. Pens, too.

October read the letter:

Dear October,

We searched the music teacher’s house and we think you may be on to something. On the kitchen counter we found newspaper articles of the stock exchange explosion and photographs of her and your French teacher at some party. They were obvious, laid out on the counter, like they’d just been viewed. We didn’t have to search at all. Maybe you want to call the police or something.

Yours,

Derek Running Water

P.S. If we solve this mystery early, will you take us to the movies again?

October’s world crashed down around her like a poorly secured series of mobiles. Maybe it wasn’t old man Santuzzi after all. Each word, each letter, each stroke of ink on the paper — “From the desk of Eileen Tischmann” — was like a chisel to October’s brain. All signs rationally pointed to Mrs. Tischmann being Mr. O’Shea’s killer. And though that brain chisel was difficult to ignore, October tried. Mrs. Tischmann was never going to win an award for educator of the year — not even among the dismal candidates at Sticksville Central — but could she really be a murderer? A murderess? This decision, she decided, wasn’t something a bunch of old photos and a wooden leg alone could determine. October had to take the investigation into her own hands from here.

October arrived at music class a bit later than planned on Thursday afternoon — the result of an involved debate with Yumi over Mr. Tim Burton’s take on the Headless Horseman — so she missed the chance to talk with Mrs. Tischmann before the period began. She wasn’t sure that would have been the best time to confront her, anyway — she could imagine the palpable tension: October knowing, Mrs. Tischmann knowing that she knew, her murderous intent, each downward stroke of her conductor’s baton a wishful knife in October’s belly.

From the instrument room, October retrieved her trombone. She assembled the slide and bell before inserting the terrifically cold mouthpiece. October blew silently into the mouthpiece to warm it on her way back to her seat. She waved to Stacey, armed with his mallets, and sat down in the back row. Ashlie Salmons, back from yesterday’s absence, swung around in the front row, and glared at October. It was the first time she’d seen Ashlie since giving her a friendly elbow to the stomach. Ashlie’s pointy face split into two grinning rows of near-perfect teeth, which is not the normal sort of reaction a person has to someone who recently physically assaulted her. Understandably, October was a bit apprehensive.

Mrs. Tischmann opened the class by leading the students in a few scales. Everyone was still treating her like an untalented but well-liked relative at karaoke. All polite smiles. She flapped her arms joyously to the beat Stacey provided, her wild hair bouncing in time.

“Okay, everyone!” she sang. “Now for a little fun, take out ‘Dancing in the Street.’” Apparently, Mrs. Tischmann’s dictionary had a different definition for fun than yours or mine. “Remember — put some soul into it.” Mrs. Tischmann winked and made a strange grimace, and October hoped she’d never have to see that face again.

Two and a half minutes into the class’s soulless version of “Dancing in the Street,” their musical momentum collapsed. October saw the devastation as an opportunity, and shot her arm up in the air. Now, she thought, was the time to arrange a meeting with Mrs. Tischmann so she could ensure an intervention of sorts after class. Mrs. Tischmann, her head still reeling from the class’s butchery of Martha and the Vandellas’ hit single, spied a pale hand above the brass bells and horns.

“Yes, October?”

“Sorry, Mrs. Tischmann. I know this doesn’t have anything to do with the song, but could I talk with you about something after class?”

“That would be fine,” said Mrs. Tischmann. “I guess I’ll just have to wait to discover what secret topic it concerns.”

“It’s probably about her appointment with the school therapist,” offered Ashlie Salmons, at a decibel level the entire class could enjoy. The scamp. “Principal Hamilton’s set up a bunch of therapy sessions for her.”

Now, October had learned from her dad that seeking professional help for one’s problems was nothing to be ashamed of. Unfortunately, Ashlie Salmons was not so enlightened, nor were many of October’s classmates who began to whisper to one another and snicker. Stacey crashed his cymbals together raucously, which seemed to be a misguided, but somewhat sweet attempt to drown out the gossip and laughter. Or he just liked making loud noises. Hard to say with him.

“That’s enough! Stacey! October! Ashlie!” shouted Mrs. Tischmann, attempting to regain control of the class. “Ashlie and October — pack up your instruments. You’re both going straight to the office. You can talk to Principal Hamilton about your little feud.”

“But I didn’t do anything!”

“October,” she continued, turning her attention to the goth girl whose face had turned an unfortunate shade of bright red. “I can meet with you at the end of the school day if you still need to talk. But right now you need to go to the front office with Ashlie.”

October nodded her head trying not to cry, yet again. Maybe she could make it through a full week without bawling like a thirteen-year-old who was not yet ready for high school. She followed Ashlie Salmons out the door — two prisoners unwillingly chained together on their way to execution.

They only made it about twenty locker lengths before the accusations started.

“Why can’t you just leave me alone? I already have to see the school therapist because of you!”

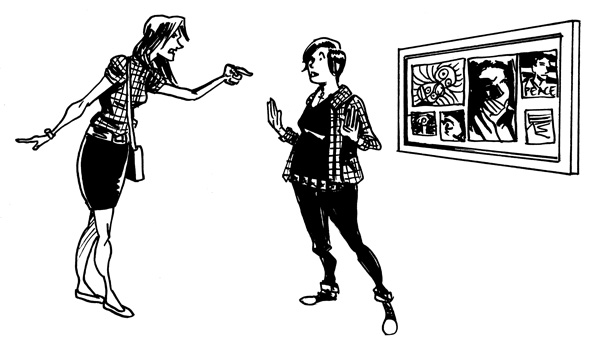

“Think you’re the only one, Zombie Tramp?!” Ashlie snarled back, her accusing finger in October’s face, the nail splashed perfect Vanilla Dreams white with polish. “Did Mr. Hamilton not inform you of the good news? We’re talking with Mr. Lagostina together.”

“Oh, barf,” October said. It seemed the day couldn’t get any worse.

“I know, right? Zombie Tramp attacks me and I need to see the therapist? In some sort of group therapy session? Cry me a river, Schwartz.”

“Why won’t you leave me alone? I only wanted to know what you saw that night Mr. O’Shea died. No one cares about you smoking!” October was on the verge of the verge of tears. Not quite there yet because fury was now her dominant emotion. “I hope you never pass grade nine.”

“You shut up about that,” seethed Ashlie. “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“I think Mr. O’Shea was killed, and I need your help!” October exploded.

If not for the music students who were currently destroying “Love Shack,” the outburst surely would have disrupted classes along the art hall. October turned around to face some terrible grade ten art projects in the hallway’s display case. No way was she going to cry in front of Ashlie Salmons. She’d love it too much. There was a very real possibility, dear readers, that Ashlie was energized by the tears of unpopular girls.

“Are you serious? Are you still on about this?” she asked.

“Yeah,” October sniffed. “I know it’s stupid.”

“You should really tell my mom about this,” she commented. October couldn’t figure out why Ashlie had instantly become her closest confidante.

“You don’t . . . think I’m crazy?”

“I do,” Ashlie admitted. “But I can’t imagine you’d keep bugging me about this crap if you didn’t have good reason. You’d be a glutton for punishment,” she reasoned.

“I guess.”

“I’m horrible to you and your stupid friends.”

“Yumi and Stacey.”

“Those are both girl’s names. Is Yumi Kung Fu Zombie Tramp?”

“Yeah,” October said, calming down a bit.

“So, she’s not even Chinese?”

“Who cares?” October said, exasperated.

“I mean, why even talk to me at all if you could avoid it, right?” Ashlie reasoned.

Drained of weeks and weeks of anger, October aimlessly attempted random number combinations on nearby lockers while she waited for Ashlie Salmons to respond with something, anything that could explain her actions.

“Listen,” she said. “I hate my mom,” she said, rifling through her little green purse for gum. “She said I can’t date Devin. She’s still angry with me for flunking last year. Witch. So I’m a little self-conscious about getting in more trouble; I don’t want Crown Attorney Salmons finding out her daughter was smoking and drinking in the parking lot when she was supposed to be in volleyball practice, okay? She’s already all over me about schoolwork. You wouldn’t understand. You’re like some ten-year-old whiz kid, right? Stupid baby.”

“I’m thirteen.”

“Whatever. Let’s call a truce. You don’t tell anyone about Devin and me at the school that night, and I can tell you everything you need to know. Full eyewitness account.”

“Really?”

“Yeah. What do you want to know? Who was at the school that night? Everyone on the volleyball team, your dad, Mr. Hamilton, Mr. Santuzzi, Mr. Page, the janitor, Mrs. Tischmann . . . a lot of teachers, actually.” She looked toward the sky as she counted, as if the answers were all written somewhere over the particleboard ceiling panels.

“Uh . . . thanks. I guess.”

“Whatever. Listen, if I do this, you’ve got to repay the favour. Stop being so crazy. Elbows flying. Weird niner guys with bad moustaches shouting at me in the cafeteria. When my mom finds out about this therapy session, she’s gonna have a kitten. Give birth to an actual cat, you understand? So calm down. I know I mess with you, but you’re a freak. Just deal with it like a Spartan, okay? And let’s try to get out of this therapy session as unscathed as possible.”

“Okay . . .”

“And there’s no way I’m going to Kaiser Hamilton’s office. We’re skipping the rest of the period and we’re not saying anything to anyone. And then we’re good,” Ashlie concluded.

Well, I don’t think any of us were expecting that about-face. Ashlie Salmons: unlikely ally to our heroine? I had just assumed she’d be unmasked as some sort of robot programmed by her math teacher to torment October until graduation. If you’re writing your own book feel free to take that idea and run with it.

“So you won’t make fun of me anymore?”

“I really can’t promise anything, kid.”

History class provided October the perfect opportunity to plan her interrogation of Mrs. Tischmann. Mr. Page had a certain amount of faith in October, much like Mr. O’Shea once had. She was sometimes able to spend entire classes doodling, writing in her book, or — more commonly the case in recent days — mentally exploring the possibilities and motives involved in Mr. O’Shea’s murder, without so much as a peep from Mr. Page.

Reminded of her budding authorial career by Stacey during yesterday’s lunch, October had begun writing down notes for questions to ask Mrs. Tischmann in her Two Knives, One Thousand Demons notebook. Occasionally, she’d add a few lines about Olivia de Kellerman, demon-slayer extraordinaire, and her ongoing battle with incredible evil. So she hadn’t really abandoned her novel entirely entirely. Her attempt to write in Thursday’s history class created an unholy hybrid of horror and a game plan for questioning her music teacher:

That was intense. Never before had Olivia de Kellerman seen the Toronto Symphony’s timpani player turn blood-red, grow fangs, and sprout bat wings from his back. As she wrenched her blade from his collapsed skull, she could see silhouettes of the lower brass section near the back of the auditorium. The long shadows and blood pouring down her forehead obscured much of her vision, but Olivia could almost swear she watched the baritone players shed their human skins and slither into the instrument room.

Um . . .

Something about something — then she shoved her knife deep into the conductor’s cummerbund region and pulled upward until she hit bone. The demon-witch howled in pain.

“Why did you kill him?” Olivia demanded. She was up to her hilt in the rancid flesh of the demon-witch who had devoured her mentor, Uncle Otto. “Why did you do it?!”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” shrieked the demon-witch, clawing at Olivia’s right hand.

“You didn’t kill him? The man who took your eye?”(Oh yeah. The demon-witch only had one yellow eye. And was totally unhappy about it.) “You had the opportunity! The motive!”

Okay, the story was getting a bit ridiculous. October realized this, too, just as she realized the shadow suddenly casting itself across the desk was that of Mr. Page.

“October, may I ask what you’re doing? Because whatever it is, it certainly doesn’t seem to involve the Treaty of Versailles. And instead, involves . . . demon-witches?”

October’s best answer was a shrug of her shoulders.

“Mmm-hmm,” said Mr. Page. “Well, if you could not do that in history class, I would appreciate it.”

October gave a little sheepish grin of agreement, and was returned a tight smile from her history teacher. So much for a little faith.

“Is it true?”

October was shoving books and binders into her narrow locker when an excitable and fast-talking Yumi Takeshi approached, demanding verification of the truth of it, whatever it was. The chains and bracelets Yumi wore jangled and clanged, so physical was her enthusiasm.

“Is what true?”

“You know,” she dropped her voice to a conspiratorial level. “That you’re in therapy.”

“Yes,” October looked around to see if anyone nearby was listening. “Where did you hear that? And why are you so excited about it?” She pushed Yumi, only somewhat jokingly. Stacey arrived at October’s locker moments later.

“Everyone’s talking about it. Stacey told me how Ashlie announced it in music class, but I just figured she was lying. Besides, it’s kind of cool.”

This was news to October. While her dad had always maintained therapy was perfectly normal and all that, he never tried to make the practice seem hip. Only Yumi could think it was cool. Her cousin was probably in therapy or something.

“Cool?” October said.

“Yeah. I mean, it’s undeniable proof you can’t be boring, right? Do boring people need therapy?”

How do you argue with that kind of perfect logic?

“People in a catatonic state need therapy and are pretty boring,” said Stacey, arguing with that kind of perfect logic.

“Whatever,” October said, closing and securing her locker. “The only reason I’m seeing the school therapist is because Principal Hamilton is making me. And the only reason he’s making me is because I hit Ashlie Salmons. And I have to take the therapy session with her.”

“What a witch,” said Yumi, in awe of her total witchery.

“Seriously,” said Stacey. “It’s those of us who aren’t injuring Ashlie Salmons on a regular basis who should see a therapist.”

“Come on . . . she’s not . . . that . . . bad,” October said, ashamed. She felt an unjustified need to defend Ashlie since their awkward truce.

“Maybe Principal Hamilton was on to something,” Yumi decided, for October had clearly lost all sense of right and wrong.

Wait a second. Yikes! Hearing his name aloud, October realized what I already had: that Principal Hamilton was still a major suspect. He has the keys to the auto repair shop. He was on site that night it all went down. What if the therapy sessions were Hamilton’s way of keeping October off the case? What if he was trying to discredit her because he was involved in Mr. O’Shea’s death? That would be pretty nefarious, wouldn’t it?

“Sorry, guys. I have to run,” said October. “I have a meeting with Mrs. Tischmann.”

October swiftly strode down the arts hallway to Mrs. Tischmann’s door. It was slightly ajar, which was a good sign she was still there, waiting for October. But waiting how? Might she already suspect why October wanted to speak to her? Think like Olivia de Kellerman, girl. WWOdKD? She’d interrogate the stuffing out of Mrs. Tischmann — her and her wooden leg. She’d strap her down and open a jar of termites. Mrs. Tischmann could be lying in wait behind the door, ready to bash a guitar over October’s head like she was in the front row of a Sex Pistols show (circa 1977). October couldn’t take a chance like that; she definitely needed to keep her head intact. The only logical course of action was to sprint into the music room and take Tischmann by surprise.

October burst through the door to find a very confused Mrs. Tischmann at the blackboard, octaves and bars marked in white. If she hadn’t been convinced of October’s need for psychiatric help before, this had surely changed her mind.

“October, are you all right?” Mrs. Tischmann looked concerned. “Is someone chasing you?”

“Uh . . . no. Just . . . practising for the track and field team.”

“We don’t have a track and field team.”

So much for quick thinking. After all the excuses she’d made recently, you’d think October would get a little better at it.

Mrs. Tischmann ignored the fact that her student believed she was on the school’s nonexistent relay team and apologized for the day’s music class. “I’m sorry about what happened today, October. I’m sure Principal Hamilton reprimanded Ashlie and I don’t think it will happen again. Now, what did you want to talk about?”

It was now or never, October reasoned.

“Your leg.”

“My leg?” Mrs. Tischmann was taken aback. “What about it? You know now that it’s wooden. But I don’t like to make a big deal about it.” The curls of her hair bounced as she rapped her knuckles against the faux leg.

“I would,” October gulped. “I would make a big deal about it . . . if I lost my leg in the bombing of the Montreal Stock Exchange.”

Mrs. Tischmann stared at October as if her head had begun dispensing a strawberry milkshake. “How do you know —”

“Did you know that Mr. O’Shea was once a member of the FLQ, Mrs. Tischmann?”

Mrs. Tischmann looked like October had taken that strawberry milkshake, thrown it at her, then slapped her — Mrs. Tischmann’s face was now a hundred shades of red. “I don’t think we should talk about this,” she said. “I think you should leave, October.”

October’s heart was like a hummingbird caught in a mailbox. She was now certain Mrs. Tischmann had something to do with Mr. O’Shea’s death, but she didn’t know what to do, what question to ask next, how to act. She needed to make her move fast, because Mrs. Tischmann was pushing her out through the door.

“No, please!” October begged. “I just want to talk to you about Mr. O’Shea!”

“I will not just sit here while you speak ill of the dead,” she tried to angle October out of the doorframe without manhandling her. “Mr. O’Shea was a very kind, very special man.”

“I agree,” said October desperately. “And I want to know why someone killed him!”

“Killed him?” Mrs. Tischmann stopped trying to force the door closed. “Do you actually — oh my, you think I . . . ? Come in. Close the door.”

October did as she was told, though she feared she might regret closing herself in a room at the far end of a hallway after school hours with a possible killer. But such are the impulsive choices one makes in life.

“Come here. Sit here,” Mrs. Tischmann whispered, and sat down in one of the plastic orange chairs that normally comprised the flute section. October joined her. “What makes you think Mr. O’Shea was killed? It was a horrible way to die, but it was an accident.”

Either Mrs. Tischmann didn’t kill Mr. O’Shea, or she had a second calling as a drama teacher. Still, October thought it wise to limit what information she revealed; for example, explaining how she found Mr. O’Shea’s storage unit or that she knew what the official police report said might be problematic.

“My dad was questioned by the police about it,” she said, which wasn’t a total lie. “Mr. O’Shea was crushed by his own car, when the switch for the mechanical lift was broken.”

Mrs. Tischmann winced, as if the car was crushing her instead. Sorry, kids. That was a really insensitive way to describe it.

“How could someone crush himself? And the right-hand switch was the broken one, but Mr. O’Shea was left-handed, right?”

“You’re right,” Mrs. Tischmann gasped. “I thought that too. When he died, I said to myself, Terry wouldn’t be so careless. So stupid. And he’d never take his own life. But then I thought I was being ridiculous. Who’d want to kill Terry?” Mrs. Tischmann looked wistfully into space.

October didn’t know if she was going to continue speaking, so she interrupted. “Uh . . . I thought you might.”

“Never! Oh, I would never . . .”

“But you knew he was part of the FLQ? They took your leg!”

Mrs. Tischmann then explained how she and Mr. O’Shea had been good friends, precisely because he had been part of the FLQ. This confused October at first, but made more sense as she continued her story.

When Mrs. Tischmann landed a teaching job in Sticksville, Mr. O’Shea realized within a month who she was, where she had worked, and most importantly, why her one leg was wood and screws instead of flesh and bone. A couple of months later, he asked Mrs. Tischmann out for coffee so they could speak privately. Over hot caffeinated beverages, Mr. O’Shea told Mrs. Tischmann everything — his old name, his old life as Henri LaFleur, his unwitting membership in the FLQ, how he had purchased the timer for the Montreal Stock Exchange bomb, how he’d left Quebec, and changed his identity. Most importantly, he told her that he’d spent every day of his life since the explosion trying to atone for his actions. He’d studied the newspaper clippings and magazine articles about the stock exchange bombing and he knew the names of all twenty-seven people injured that day.

Mrs. Tischmann had been shocked. She hadn’t thought about the attack in years, and now this colleague was informing her that he was somehow responsible for the lack of feeling below her knee. Mr. O’Shea said he wouldn’t beg for her forgiveness; he felt he didn’t deserve it. But he wanted her to know what he had done. Immediately after he told her, she just stirred the cream in her coffee and could think of nothing to say. It was all too painful and strange. Mr. O’Shea simply apologized, left five dollars on their round table, and left. About a week later, she forgave him — not that she ever told him she had. Instead, she just became a close friend.

“And you kept his secret?” asked October, amazed, not only by Mrs. Tischmann’s story, but by the whole world of the hidden lives of teachers. Every teacher could have a story like this — a secret life she’d never know.

“Yes. I never told anyone, not even my ex-husband. Not my parents.”

“But . . . I mean . . . wasn’t that dangerous for him?” October stammered. “You could have turned him in at any time.”

“I could have,” she said. “But the way he told me everything, without even knowing me, really, and without any regard to how it could affect his life . . . I think he was suffering his own personal punishment.”

Mrs. Tischmann looked serene after confessing. October would bet her eye teeth — whichever ones those were — that her music teacher had told the truth, but some aspects of her story still made no sense.

“You never seemed too close to Mr. O’Shea. You weren’t even upset when he died,” October said.

“Ha. Leave it to teenagers to be blunt. Mr. O’Shea and I tried to keep our friendship something of a secret. I thought it would be the best way to keep his past hidden . . . but maybe . . . maybe it was a cold thing to do.”

Mrs. Tischmann began to cry into her hands, and then October felt really horrible. She didn’t know what to do. If it was her dad or Yumi or someone crying, she’d hold that person and say soothing things like, It’s all right or No, lots of people like you, but this was her music teacher. She wasn’t going to hug her.

“It’s okay,” October said, and awkwardly patted Mrs. Tischmann’s head like she was a dog she’d just been introduced to. She waited for an appropriate lapse of time before asking another question. “Mrs. Tischmann, what if someone else found out Mr. O’Shea was in the FLQ and helped make that bomb? Would they maybe want to kill him?”

“October,” she said, wiping her eyes and smoothing her tangled hair. “How would anyone else find out?” Uh, hello. October found out, music lady. “And even if they did, they’d just call the police. Why would they want to murder him? I’m sorry, dear, but I really do think this was just an accident. Accidents will happen.”

She began to cry a little again, and October clumsily excused herself and left the classroom. It can be very uncomfortable to watch adults cry.

Rows of pumpkins lined the stoops of Riverside Drive as October made her way home. The good news was that she could cross one suspect off her Sticksville Central suspect list. Mrs. Tischmann was too much of a wreck to be Mr. O’Shea’s murderer. She was probably still blubbering in her classroom, playing “Memories” on the piano and breaking down after a few bars. The bad news was that October had no other convincing suspects, just a laundry list of all the other teachers who were there that fateful night.

In her mind there was and had been only one real suspect: Mr. Santuzzi. Almost everything fit. October was going to enjoy nailing his butt to the wall, even though the thought terrified her. Terrifying but also enjoyable — like a roller coaster where you have to stand up during the ride. Or hot dogs you buy on the street.