THE GODS’ BREAKFAST

A half millennium ago, a canoe full of Indians rowed out to an ungainly floating house anchored at Guanaja, a palm-flecked island off the Honduran coast. Christopher Columbus had stopped by on the way home from his fourth and last trip to America, still hopeful he might find useful riches beyond an expanse of alien real estate. The Indians offered what he took to be a handful of shriveled almonds. He was mystified when a few dropped to the bottom of their canoe, his son reported later, and “they scrambled for them as though they were eyes that had fallen out of their heads.” But Columbus’s Mayan was no better than the natives’ Spanish. He returned to Spain empty-handed.

Chocolate has come a long way since then.

These days, those almondlike cacao beans that the grand Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus named Theobroma—elixir of the gods—are the basis of a $60 billion industry. From the time laborers scoop them from pods in equatorial jungles until fine chocolatiers massage them into gold-flecked ganaches, the value of a bean might increase several hundred times. But money is hardly the way to measure their worth.

One night in Paris, a friend took me to a tasting of the Club des Croqueurs de Chocolat, a circle of people who believe well-crafted

bonbons to be as vital to life as oxygen. We tried one creation after another, noting every nuance from the sheen on their coatings to subtle flashes of flavor that lingered on the tongue. With knowing nods and silent smiles, we made checks on evaluation sheets next to adjectives borrowed from the complex lexicon of wine.

Finally, sated to near stupor, we settled back to hear the tastemaster announce plans for the next session. We would, he said, be sampling the finest eclairs au chocolat that France had to offer.

“Ah, oui,” one woman breathed from the back of the room. “Oouuiii,” another added, with more power, and a third joined in with loud staccato moans: “Oui, oui, oui.” Suddenly the sedate hotel dining room was blue with the piercing shrieks of passion. Columbus would have loved it.

Like every other American kid, I grew up on Hershey bars and those colorful little blobs that, M&M’s claims aside, melted in my hand as well as in my mouth. Over the years, as an amateur food lover and professional traveler, I learned to appreciate other variations on the theme. That evening in Paris, however, showed me I was clueless, a chocolate ignoramus.

Tracing chocolate from its origins to its most elaborate final forms, I suspected, would be a wondrous journey. But only after I followed cacao into a fierce African rebellion and then stood paralyzed with pleasure at the heady scent inside Michel Chaudun’s little shop in the seventh arrondissement of Paris did I realize how much chocolate has flavored the last five centuries.

I started out by paging at leisure through Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Before long, I was delving into the themes of War and Peace.

By the end, I saw why people like my friend Hadley Fitzgerald, a California therapist of reasonable habits, would have to think a moment if the devil offered to buy their souls for chocolate. Hadley’s body and being require a daily dose.

Taken to its highest finish, cacao ends up as a palet d’or, a simple square or circle of creamy dark filling—the French call that “ganache”—inside a thin, hard covering of silky smooth chocolate,

the enrobage. At its best, a palet d’or shines with a rich brilliance. And it is signed by its maker in bits of real gold, which carry no taste but deliver an unmissable message: This is the good stuff.

I began to catch on when I savored two palets made with distinct types of chocolate from the French company Valrhona. One was Manjari, from Madagascar cacao; the other was from Gran Couva plantation in Trinidad. Except for cream in the ganache, both palets were pure chocolate.

The Manjari came in a rush of ripe raspberries. It peaked and then settled into a long, lush finish. Gran Couva was flowers, not fruit, a slow-moving cloud of jasmine that carried me away to some very happy place.

Nothing is simple about good chocolate. Some high practitioners prefer the term palet or. Either way, the old translation was “pillow of gold.” According to the Académie Française des Chocolatiers et Confiseurs, Bernard Serarady devised the name in 1870, in the town of Moulin. But Saint-Germain-en-Laye disputes that claim. In 2004, French chocolatiers convened to argue the point.

Soon I dispensed with the fancy final product and bought bulk chocolate bits from my favorite producers in the Rhone Valley, in Tuscany, in California’s Bay Area. In form, though in no other way, these reminded me of those baking chips I used to forage from my mother’s pantry.

Beyond industrial candymakers with brands we all recognize, chocolatiers come in two flavors. There are those who make chocolate from beans, from the Swiss-based behemoth Barry Callebaut to such specialists as Valrhona. And there are artisans known as fondeurs—the word means “melters”—who turn this base chocolate into high art.

France bestows upon its chosen chocolatiers the aura of philosopher-kings. Pierre Hermé, a hulking bull of a man with a delicate touch, opened his small Parisian shop on the rue Bonaparte and had to hire a press agent to ward off the journalistic swarm. Robert Linxe sold his redoubtable La Maison du Chocolat in Paris to a globe-girdling French industrialist, yet eager pilgrims still come to sit at his feet.

For chocolatiers, “chocolate” implies un produir frais, a fresh and

living thing that must be consumed within days. Yet that Hershey bar dug up after sixty years from Admiral Richard Byrd’s cache at the South Pole is also chocolate. It was made for World War II field rations. According to army specifications, it was designed to taste “just a little better than a boiled potato.” That way, soldiers would not wolf it down heedlessly. Having been frozen all those years, it was still edible. In the view of purists who disdain industrial cocoa products, it could have gone right onto a store shelf. Who’d know the difference?

And yet, purists be damned, millions still revere a Hershey bar. In a good year, the world can produce three million tons of cacao, less than half the coffee crop, but still a lot of beans. And how one likes them is a simple matter of preference.

Chocolate, in substance and in spirit, covers a lot of ground. Taken to a fine finish, it is no less nuanced than wine. If there is Ripple, there is also Rothschild.

Hernan Cortés tasted chocolate only sixteen years after Columbus sailed home. Although he noted in his letters that it just might catch on, much about cacao still remains a mystery. From bean to bonbon, the production chain is long. Few people who slave away in steamy heat all their lives to grow cacao have ever tasted chocolate. Hardly any confectioner who does the final fancywork has ever seen a cacao tree. Tropical institutes study the botany. Engineers perfect production. But for all the science around it, fine chocolate still demands a touch of alchemy, masterful sleights of hand bordering on the magical.

In its primary state, chocolate is odd-looking and often forbidding. Theobroma cacao can be an extremely picky plant. Young trees seek the dank shadows of tall tropical hardwoods; older ones like more sunlight. They also like their space. They grow only within twenty degrees of the equator but can climb up mountainsides as high as two thousand feet. And they demand a long rainy season, with deep, rich soil and temperatures that never drop below sixty degrees.

Their setting can be heart-stoppingly beautiful, under such towering monsters as Erythrina, the coral tree, with its vivid scarlet sprays of

blossoms. “The cocoa woods were another thing,” V. S. Naipaul once wrote of his native Trinidad. “They were like the woods of fairy tales, dark and shadowed and cool. The cocoa-pods, hanging by thick short stems, were like wax fruit in brilliant green and yellow and red and crimson and purple.” (For reasons I could never determine, English usage often prefers “cocoa” for both the plant, the bean, and the drink it produces; I prefer the less-confusing approach of Romance languages: cacao and cocoa.)

By the time a graceful cacao seedling grows to maximum age, about forty years, it can be as tough and twisted as a scrub oak. Its bark is often a patchwork of greenish white lichen. If well pruned, as it must be to produce quality pods, its crown of leathery leaves—most dark green, some in rich colors—forms a canopy about eight feet above the ground. Left wild, it grows three times as tall.

Cacao starts with delicate white flowers that sprout improbably from the alligator-skin trunks and limbs. Most blossoms wither and drop away. They germinate only with the help of a midge, hardly bigger than a pinhead, that lives in surrounding undergrowth. Perhaps four or five in a hundred transform over three months into bright green oval pods, no bigger than a small pineapple. They ripen to painter’s-palette shades from yellow to deep purple.

Each pod’s thick, fibrous husk protects about forty beans inside. These nestle in a sticky white pulp with the wonderfully sweet taste of an Asian mangosteen. No sensible rodent or monkey misses the chance to steal a ripe pod and spend a day gnawing its way inside. This is just as well. As pods do not fall from the tree, seeds must be transported by bird, animal, or man for a new plant to grow.

Plantation workers harvest the pods with lethal-looking hooks on poles. Using machetes or clubs, they deftly open the pods, careful not to damage the beans. The gooey mass scooped from inside must ferment for days, protected from outside air, until the mucilage drains away and dries.

At first, this was done simply to dry the beans so they could be shipped long distances without spoiling. Over the years, however, growers realized that fermentation begins to unlock the flavors inside. Now this initial step is crucial to final taste. Beans are then dried of

most of their remaining moisture, packed into jute bags, and dispatched to Europe and North America.

All of that, of course, is just the preliminary stage of making chocolate.

Those tiny midges are vital to the growing process, but a harrowing range of other insects and diseases can kill the trees or destroy their pods. A plague of witches’-broom beginning in 1989 all but drove Brazil out of the cacao business. Maladies with names like pod rot and swollen shoot can wreak havoc. If trees lack moisture for too long, their leaves drop off and they die.

By the time Cortés discovered the Aztecs’ cacahuatl, anthropologists say, earlier inhabitants of the Americas had been drinking it for at least a thousand years. What the Spaniards found was a domesticated variety of T. cacao, known as criollo, which is native to Central and South America. Its slim oblong pods contain pure white aromatic beans that are the source of particularly prized chocolate. But it is finicky. It grows relatively few pods and only under highly specific conditions. It is susceptible to pests and disease. And it languishes in unfamiliar surroundings.

Once established in the New World, the Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch brought cacao trees to their tropical colonies overseas. But, despairing of the fragile criollo, planters relied on a different variety known as forastero, which means “foreigner.” It is hardier and more productive, and it travels well. Its beans are purple inside, unlike the white centers of criollo. And they lack criollo’s fragrant richness.

As late as the mid-twentieth century, growers in Mexico tore out old criollos to plant forasteros that produced a much bigger—but a much inferior—crop.

Spain dominated the early cacao trade. As demand increased for chocolate in Europe, kings in Madrid kept close watch on their lucrative crop. After a century, though, their monopoly was threatened. Portuguese colonizers grew cacao in Brazil, and Dutch sailors also brought trees to Southeast Asia. In 1822, trees were transplanted from Brazil to Portugal’s outpost of São Tome, off the West African coast.

Soon afterward, cacao was also growing in the neighboring Spanish island colony of Fernando Po. Late in the nineteenth century, an African plantation worker smuggled seedlings from Fernando Po to the nearby British colony on the mainland, the Gold Coast, now Ghana. Trees spread to the French Ivory Coast across the border and into Nigeria.

In the early 1700s, a Caribbean calamity resulted in a third variety of T. cacao. Something that history records as the Blast devastated Trinidad. Today, no one is certain whether this was a monster hurricane or a deadly blight. Either way, it wiped out the island’s criollo trees. They were replaced with the hybrid trinitario, which has since found its way around the equator.

A fourth variety, nacional, was developed in Ecuador, with a distinctive spicy flavor named for the region where it grows, Arriba. It is, essentially, a better sort of forastero.

During the first part of the twentieth century, as a new industry fed a fast-growing chocolate craze, England and France muscled ahead in the world cacao market with their African fosasrero. Today, 70 percent of the world’s beans come from Africa. Ivory Coast alone produces nearly half of the global crop—the worse half.

Worldwide, about 15 million acres are planted in cacao. And 90 percent of it is grown by families, perhaps with a few hired hands, on holdings of less than twelve acres.

Pure criollo goes into perhaps I percent of all chocolate, and trinitario beans account for about 10 percent. Like vintners and olive-oil makers, chocolatiers have started to examine the raw material they had taken for granted over generations. With a great chocolate awakening that coincided with the turn of the millennium, single varietals were suddenly all the rage. And the most prized was the vanishing criollo.

In Trinidad, a gene bank protects some of the oldest forms of T. cacao. And some experiments are under way. With Venezuelan government aid, botanists are trying to revive the elusive rich taste that once flavored so much of the Americas. A plantation south of Lake Maracaibo that started with three hundred trees planted late in the 1990s may eventually help bring back a glorious lost flavor.

Archeologists say that the Olmecs, in what is now Mexico, drank chocolate a thousand years before Christ. Only a limited amount has been learned about these enigmatic early people who left behind huge stone gods with high domed foreheads, sad eyes, and fleshy lips. Stunning jade masks and other archeological evidence suggest a complex civilization. Nothing is known about what they liked for breakfast. But, like other Mesoamerican Indians, they must have loved to suck the sweet pulp from ripe cacao pods.

The highly cultured Mayans were the first to make a sacred drink of cacao. They roasted and ground the beans, mixing the powder with chilies, herbs, and wild honey. Cacao was at the top of the list when tribute was offered to their rulers. It went into the tombs of kings. By the time Columbus arrived, cacao beans were the coin of the realm. They were used for trade between the Maya and the Aztecs who settled to the north, in central Mexico, in the thirteenth century.

The beans were money that grew on trees, which explains why those Indians at Guanaja were loath to lose any in the bottom of their canoe. Centuries on, that seems like a noble concept. How can you hoard coins that so quickly dry up and crumble away?

Among tribes in Nicaragua, Francisco Oviedo y Valdés reported, a rabbit cost ten beans and a slave was worth one hundred. Dalliance with a prostitute cost eight to ten of the shriveled edible coins; this was negotiable. The currency system was based on 20. Each four hundred beans were a Zontle. Twenty of those made a xiquipil. And so on.

By the time Cortés arrived, the Aztecs had elevated their cacahuatl to holiness. The drink was made with complex blends that sometimes added cornmeal to the fiery chilies and aromatic spices. Bernal Diaz del Castillo, the mildly reliable chronicler of the Conquista, reported that the emperor Montezuma faced his harem of two hundred wives only after drinking fifty chalices of spiced cacao. The supposed aphrodisiac effect of the Aztecs’ chili-laced chocolate inflamed the Spanish imagination.

“Their main interest in life is to eat, to drink, to debauch, satisfying a wild lust,” Oviedo y Valdés wrote, with what seemed like a touch of envy. At another point, he added details: “It is the habit among Central American Indians to rub each other all over with pulpy cocoa mass and then nibble at each other.”

While some early Mesoamericans relied on wild honey with a kick of hot chilies to flavor their chocolate, the Aztecs took more trouble. Cortés notes one secret recipe: 700 grams of cacao, 750 grams of white sugar, 2 ounces of cinnamon, 15 grams of pepper, 15 grams of clove, 3 vanilla beans, a handful of anise, some hazelnuts, musk, and orange blossoms.

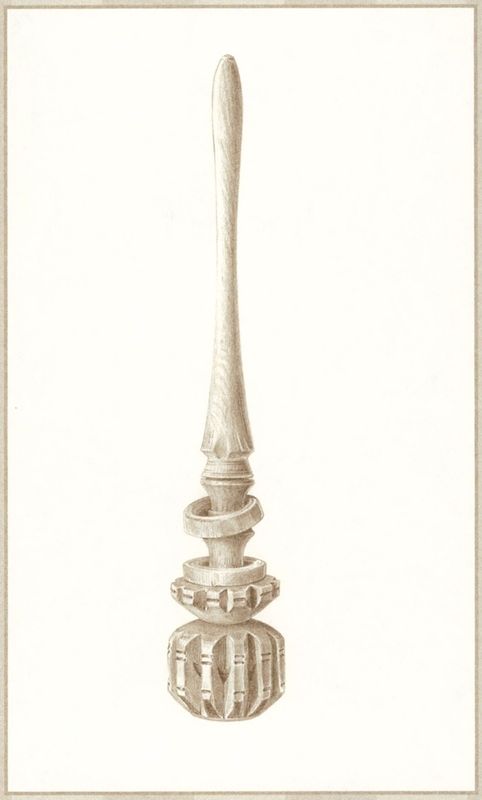

Mexicans today still grind roasted cacao beans and sugar into a grainy viscous paste that is mixed in a clay vessel, a jarro chocolatero. Chocolate and liquid are whipped with a molinillo, a wooden stick with rings carved at the end. As this is hard work, the job is left to women, who spin the stick between their palms at a furious pace until delicate froth builds atop the liquid. Purists still use water, but milk is now more popular. Cinnamon is usually added, and some special drinks include corn.

Cacao fascinated Cortés. “The divine drink of chocolate builds resistance and fights fatigue,” he wrote to King Carlos I. “A cup of this precious drink permits a man to walk all day without food.” He described how, in Montezuma’s court, the cacahuatl was served in golden goblets with great ceremony. When he came home in 1527, Cortés brought beans to his own emperor. If Carlos I liked the new beverage, he left no word. For two generations, chocolate was a mysterious rarity available only from travelers who brought home their own supply. Then in 1585 a cargo ship from Veracruz brought enough beans in its hold to create Europe’s first chocolate fiends.

Cacao was processed in monasteries and nunneries. The Jesuits made a specialty of it, experimenting with new concoctions. They maintained plantations, using the income to build churches and schools. King Felipe II, a man of great appetites, developed a taste for chocolate. By the late 1500s it was the royal rage.

Almost immediately, the church found itself mired in polemic. Was cacao a miracle drug or a sinful stimulant? Was it food or drink? In 1569, Pope Pius V set things straight. Cocoa, as a beverage, was permitted during Lent. And because the pontiff found it so repugnant, he declared there was no danger of its causing moral harm.

Naturally, there were holdouts. One colonial bishop, furious that cocoa-slurping ladies in the back pews were disturbing the Mass, put his foot down. The women refused to relent and moved to another church. And the bishop, inexplicably, died of poisoning.

Physicians and scientists disagreed violently among themselves, but the pro-chocolate faction carried the day. Juan de Cardenas, in a book called The Problems and Marvelous Secrets of the Indies, wrote in 1591 that chocolate’s high fat content had a positive impact on the body’s “animal heat.” Thomas Gage, a Scottish medical missionary, declared, “A glass of good Chocolate restores and, above all, fortifies the stomach.”

After the Jesuits, it was the Jews. Expelled from Spain and then Portugal without many options, Jewish artisans settled in the French Basque country, just over the border in Bayonne, where they made the first French chocolate early in the seventeenth century. But, hemmed in by the Pyrenees, they had little commerce with Paris.

The Spanish managed to keep a lock on cacao for most of a century. But then it reached Flanders and Holland, at the eastern edges of Spain’s European empire, and the monopoly collapsed. Francesco Antonio Carletti, a Florentine merchant, brought it to Italy in 1606. Soon, chocolate salons opened in Venice and Florence, and then in Perugia and Turin. Italian chocolate lovers added a touch of elegance, devising new ways of preparing cocoa and serving it in specially designed porcelain.

In 1615, a fourteen-year-old Spanish princess named Anne of Austria was dispatched to marry the French king, Louis XIII, who was only a few days older. Refusing to go without her chocolate, she brought cacao beans to Paris in her luggage. Before long, as is their wont with edible items that come to their attention, the French appropriated chocolate.

France reinvented the exotic import, folding it into a culinary culture that accompanied an enthusiastic mission to civilize a less enlightened world. For late-Renaissance Parisians bent on the good life, cacao quickly established itself as the drug of choice. It was considered an energizer, a mood lifter, and, still, a powerful spur to the libido.

Among the earlier rituals of French royalty was to receive guests for hot chocolate. A chosen few were invited into palace bedchambers at midmorning, and servants poured breakfast from silver jugs.

Cardinal Richelieu was an immediate cacao addict. He drank chocolate to calm his flaring temper. Cardinal Mazarin, an intimate of Anne, was so smitten by the new drink that he employed his own personal chocolate maker.

David Chaillou was the first official chocolatier in Paris. A royal patent in 1670 granted him “the exclusive privilege of making, selling, and otherwise dispensing a certain composition named chocolate.” He concocted a range of variations on Spanish recipes. Although he catered mostly to the aristocracy, his customer base was huge.

A year before Chaillou went into business, another cocoa-loving Austrian princess married the next Louis. The wedding took place in Saint-Jean-de-Luz near Bayonne—and all that Jewish-made chocolate. The king preferred red Burgundy, commenting once that the new Spanish drink “fools hunger and fails to fill the stomach.” Not so, the queen.

“The king and chocolate were the only two passions of Marie-Therese,” according to one unsigned biography I chanced upon. It was not clear if that was her proper order of preference.

For the next hundred years, until the French Revolution, every Louis in line found himself involved with chocoholic consorts. Madame de Maintenon insisted that Louis XIV, the Sun King, serve chocolate on all grand occasions at Versailles. Louis XV’s favorite mistresses craved the stuff for differing reasons.

The Marquise de Pompadour fed the king chocolate to arouse his passions. Without it, she confided to friends, he was “dead as a cold duck.” She sipped cocoa herself to make it through the night. Madame

du Barry, unsatisfied by the monarch’s panda-like libido, dispensed chocolate to her string of lovers so they could keep up with her.

Marie-Antoinette, she of let-them-eat-cake fame, was yet another Austrian who came to France with chocolate in her baggage train. She also brought her own Viennese chocolatier, whose specialty was a brew mixed with orchid powder, orange blossoms, and almond milk.

Chocolate figured prominently in the letters of Madame de Sévigné, which kept track of a grand and gay seventeenth-century France. At first, she loved a hot cup of cocoa, whipped with water and sugar into lush foam by the servants who attended her as she traveled about the country. When her daughter left Paris to join a new husband as Madame de Grignan, la Sévigné lamented the absence of cocoa in the distant Ardèche.

And then she went off chocolate completely, fearing it might burn the blood. In 1675, Madame de Sévigné wrote to her daughter and favorite correspondent of the misfortune that had befallen a countess of their circle: “She drank so much cocoa while with child that she bore a baby who was black as the devil and died after a few days.”

Enthusiasm in France spread across the Continent. Chocolate houses thrived, along with their own special paraphernalia. Porcelain makers produced patterned versions of a cup and saucer known as la trembleuse. The cup fitted snugly into a raised ring on the saucer to keep aged, trembling wrists from spilling hot cocoa.

Chocolate, coffee, and tea all captivated Europe at about the same time, and each made its impact. Coffee, the cheapest, was a man’s drink, taken in clublike public houses along with another exotic import, tobacco. Tea was twice as expensive as coffee, with a more genteel following among both males and females. But, after all, it was only hot water and wet leaves. Chocolate, at double the price of tea, was the noble newcomer.

About the time Chaillou received his royal patent, a forgotten Frenchman opened London’s first chocolate shop at Bishopsgate. Unlike the aristocratic clientele in Paris, his customers included ordinary Londoners, and he started a new trend. Chocolate houses sprang up, rivaling the popular coffeehouses as a place to meet friends, play cards,

and discuss the day. White’s opened on St. James’s Street in 1697, elevating the cocoa ritual to high art. Men in fussy wigs and breeches hobnobbed with ladies in flowing gowns in rooms decorated with sumptuous gilt moldings. Patrons could buy theater and opera tickets as they whiled away afternoons. The nearby Cocoa Tree offered similar fare in an ambiance dominated by Tory parliamentarians arguing about politics.

Samuel Pepys, a denizen of London clubs who was not easy to impress, recorded in his diaries a tepid reaction to his first taste of “Tee.” But he later noted his judgment on what he called Jocolatte: “Very good.”

The English, as usual, set a different course. In 1674, two different pubs—the Coffee Mill and the Tobacco Roll—offered chocolate to eat. Cacao was not just for cocoa. The prototype candy bars they made were coarse and, by all accounts, not that tasty. But here was a quiet milestone that changed the world. It started a global craving for chocolate in every imaginable solid form, which, three centuries later, grows yet more intense every year.

Europe took time out for a revolution in America and another in France. But then, under a Napoleonic calm, artisan chocolatiers lost no time opening up in Paris. Debauve & Gallais was established in 1800 on the rue Saint-Dominique. It is still around. In 1807, the first gastronomic guidebook to appear in France, Grimod de la Reynière’s L’Almanach des gourmands, raved about a little shop at 41, rue Vivienne.

“We enter the superb store of M. Lemoine, drawn by an ingenious arrangement of liqueurs, chocolates, and bonbons,” it began. “The unctuous chocolate owes this eminent quality to new methods that M. Lemoine uses to mix his chocolate.” The guide also praised Tanrade, on the rue Neuve—Le Pelletier, for “exquisite chocolate prepared with cacao selected with uncommon care.”

But M. de la Reynière had not seen anything yet. The nineteenth-century innovators were still puzzling over their early experiments.

The first breakthrough came in 1828, in Holland. Coenrad Van Houten found a way to extract cocoa butter and then make powder from the remaining mass. By blending some of the separated cocoa butter with sugar and adding it to the powder, he could mold chocolate.

In 1875, after eight years of trying, the Swiss inventor Daniel Peter worked out a way to combine milk with chocolate. He was helped by Henri Nestle, whose dabbling in dairy science evolved into the largest food empire on earth. No one had been able to mix fat in chocolate with water in milk. Nestle condensed milk, eliminating the water.

Another Swiss, Rodolphe Lindt, took chocolate to a higher plane. He developed the technique of conching—named for the shell-shaped troughs he used—which brings out chocolate’s true texture and taste. A heavy roller moves back and forth through molten chocolate to break down and blend the components while releasing acetic acid and other unwanted volatile elements. Mainly, the process allows full flavor to develop in the mixture. Lindt’s original procedure took several days, and serious conching still does.

As confectioners perfected their art, others worked at each step of the complex supply chain that brought raw cacao beans from distant equatorial forests. Growers found ways to coax more production from trees that resisted mass planting. Shippers carried sacks of beans across great expanses of ocean, mindful that a moldy hold or a careless crew could ruin their precious cargo.

At the same time, artists across Europe sought to capture on canvas this exotic, erotic new flavor. Jean-Étienne Liotard’s La Belle Chocolatière, painted in 1743, depicts a prim serving girl in reverent devotion to her task: delivering cocoa to her mistress. His later Le Petit Déjeuner features the mistress, lips almost quivering in expectant pleasure as the tray approaches. Both capture the fashion of the time: Chocolate is served in a lovely Meissen polychrome cup and accompanied by a glass of water.

The eighteenth-century paintings ranged from chaste to downright sinful. François Boucher, in Le Déjeuner, showed a happily functional family in a cozy kitchen starting their day with a long-handled silver

pitcher of cocoa. Noel Le Mire, in La Crainte, portrays a bare-breasted, reclining woman in voluptuous throes reaching for a similar pitcher on a nearby table. An overturned chair suggests something besides breakfast has just taken place.

By the late 1800s, Europeans were used to chocolate, and they wanted more. It was time for industrial advances. Germans were early masters of big chocolate. Five brothers named Stollwerck were obsessed with finding better ways to do things at their fast-growing factory. With great gears and flapping rubber belts, they mechanized each of the crucial steps in production. Chocolate bars were packaged in fancy dress, and colorful posters that touted them are now worth fortunes to collectors of commercial art.

Heinrich Stollwerck quite literally fell into his work. He was adjusting a blending machine of his own invention, in 1915, when it exploded. He lost his balance and drowned in his finest chocolate.

In the twentieth century, the new advances were backed by big money. Large companies shook up the small world of craftsmen chocolatiers. And, at times, the selling of sweets has been just about the nastiest business on earth.

In the United States, Forrest Mars and his sons fought bitterly among themselves before shaping a company that squared off against a common foe, Hershey. Their war was over market share. In England, however, the ugly struggle between Cadbury and Fry was all about beans.

Fry and Sons opened in 1728, the first entrepreneurs to pioneer big chocolate in Europe. Early in the 1900s, Cecil Fry, together with another well-established English Quaker family firm, Cadbury, arranged to import South American cacao. But the Cadburys made secret deals with growers to starve their partner-rival of his supply. Bad blood acquired venom over time.

When Fry died, mourners filled Westminster Abbey for his funeral. His widow watched the Cadbury patriarch arrive late and make his way among the silent pews. She rose to her feet and shouted, words echoing in the great vaulted cathedral: “Get out, Devil.”

These days, the company Nestle built now counts $65.5 billion a year in sales, and about 12 percent of that is chocolate. Nestle nearly bought Hershey Foods in 2002 for something close to $11 billion. Other candy conglomerates, with roots in the nineteenth century, operate on a grand global scale. Big is not necessarily bad.

Pierre Hermé, for instance, does not turn up his nose at industrial sweet stuff. In a pinch, he says, he’ll eat a Hershey bar. He is especially fond of France’s red-wrapped Daim, toasted toffee covered in chocolate, on the order of a Heath bar. But Hermé is clear on the subject.

“Tout ça, c’est ne pas du chocolat,” he says. “C’est de la confiserie.” None of that is chocolate; it’s candy.

Fine chocolate is made from high-quality beans that have been treated well from the time they are taken from their pods. A slip-up or a shortcut at any of a dozen crucial stages will reveal itself in the tasting.

Chocolatiers agree on a crucial point: As with wine, olive oil, or anything else elaborated from nature, quality depends upon the basic material. Anyone can make a mess of good cacao, but it is next to impossible to produce an excellent chocolate from inferior beans.

As more people catch on to the secrets of good chocolate, demands increase dramatically for a limited supply of what the world market calls “flavor cocoa.” Big players swing their weight at every chance. Small ones develop personal ties and nurture them with care. Sometimes buyers simply show up and make a deal. But in most cases, tradition-bound systems lock in the privileges of middlemen who are reluctant to lose their cut.

And the competition can get vicious. One European firm had to recall its agent in Brazil after he sought permission to murder a neighbor who kept moving the stakes that delineated the company’s plantation.

Even the best beans arrive from the tropics in an unpredictable state. Producers sometimes load up sacks to cheat on the weight. A thorough sifting removes sizable stones, motorbike gears, barnyard droppings, or the odd pistol. Washing cleans away other contaminants except for microbes killed in later stages of processing.

With all of today’s technological advances, the final process of

making chocolate still dates back to those nineteenth-century breakthroughs.

After roasting and winnowing to remove the husks, beans are broken into cotyledons—nibs—of pure cacao. When ground and heated, nibs turn to molten cocoa liquor. From some of this, cocoa butter is separated out, and the remaining cocoa powder is used for drinking or baking chocolate. But most of the liquor is further refined. Extracted cocoa butter is blended back in to smooth its texture. Sugar is also added, depending upon the sweetness required.

The molten mixture must then be refined. Quality manufacturers use a five-roll mill that progressively breaks down particles until they reach a velvety smoothness. Then they are ready for the conche.

Finally, the chocolate is tempered. The French and Belgians call this last step temperage, and the best of them worship it. Chocolate is heated to a carefully determined degree and then quickly cooled. Temperatures vary according to the mix. This seemingly simple step is what marshals the molecules so the finished chocolate ends up creamy-smooth and shining.

There are, of course, variations. The British Royal Society of Chemistry’s primer on the subject runs to 170 pages of fine print, with enough formulas and diagrams to confound a molecular biologist. The venerable factory of Lloveras, near Barcelona, makes to order its Universal, which combines many of these steps. But the basics do not change.

Big producers use complex production chains to ensure clean and consistent repetitions of exactly what is ordered. The Mars family loses no sleep worrying that someone will stamp an off-center m on one of their little candies. A Cadbury’s bar tastes pretty much the same, anywhere and anytime, over its very long life span.

But these companies cannot use the best of scarce ingredients and still price competitively. Shelf life almost invariably comes at sacrifice to flavor. Expensive chocolate is not necessarily the best. But the best chocolate is rarely cheap.

This is often not obvious. A Hershey bar falls into the category of McDonald’s; love it or hate it, what you see is what you get. Hershey’s company history is a well-known part of American lore. But much of

the world chocolate industry thrives on corporate flimflam. Cachet sells, and names are not changed in order to confuse the innocent. Just because something is labeled Lindt does not mean that Rodolphe’s great-grandson is in the back licking his finger to make sure each jug of milk comes from clover-sated cows.

A company that traces its history back 150 years might be technically correct in using the founder’s name if it overlooks all of the intervening takeovers and makeovers. But artisan chocolate can quickly lose its quality when kicked into mass production.

In the end, the common boast of lineage—“since eighteen-whatever”—means no more than it does on a restaurant façade. It matters little if some culinary genius started the business generations ago. For people who appreciate good food, all that counts is the chef in the kitchen when they sit down to eat.

Older Belgians fondly recall Joseph Draps, who named his handmade chocolates after the long-haired rich lady who rode naked on her horse through the streets of Coventry to protest a tax her husband imposed on peasants a thousand years ago. But in the mid-1960s, the little family company melted into the American conglomerate of Campbell’s Soup.

The success of Godiva is partly because so many people believe that Belgian chocolate is superior to all others. From my first day on the chocolate trail, I was obsessed by this obvious and overriding question: Who does make the best chocolate?

Consumption figures suggest Swiss chocolate is the most popular. Switzerland sells the most chocolate per capita, by far, at nearly twenty-four pounds a year. But the figure is high also because tourists buy so much to take home as gifts. Americans consume only half as much; the French, less than that.

Belgium is certainly the most serious about its chocolate. After the New York Fancy Food Show, I went to a cocktail party at the Belgian consul general’s home. Six people I had never met cornered me with the same reproach: “I hear you think the French make better chocolate than the Belgians.” This, I imagine, came from a remark I’d made several days earlier to provoke a stuffy Belgian.

In Brussels or Bruges, shops with an artisan air seem to dominate every square and street corner. But most sell industrial chocolate under old family names. Belgians made their reputation with the ballotin, a brilliant stroke of marketing by Neuhaus. This is a simple domed box, in assorted sizes, which presents the contents within as something of value. A few excellent chocolatiers fill their ballotins with real treasures. Others offer little more beyond fancy wrapping.

Pierre Marcolini, an innovative Belgian with grand dreams, shook up staid Brussels with creations that blended subtle teas and pungent fruits with his dark chocolate. In Paris, Pierre Hermé paid him what he considered a high compliment: “Marcolini makes French chocolate in Belgium.”

In fact, nationality is not much of a guide. Each country has its traditions. Belgians prefer thicker molded coatings and more fresh cream in their centers. Italians lean toward dark chocolate with hazelnut. Swiss like sweet milk in quantity. Some Americans now make some wonderful stuff that goes a long way beyond Milton Hershey. Even the Spanish, who brought chocolate to Europe but then dropped from the picture, now offer remarkable innovation. But in the end, chocolate making is a personal art, and people like what they like.

All of that said, I’d like to log a simple request: If anyone ever banishes me to a desert island with only one style of chocolate, please make it French.