THE BITTERSWEETEST TOWN ON EARTH

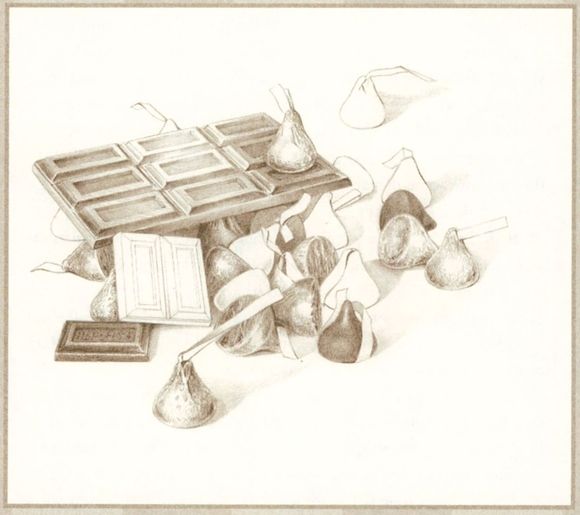

Paul Kay, charging toward his second birthday with the chipped teeth of a devil-may-care toddler and a sunny grin for just about everything, frowned at the six-foot-high silver foil blob with a long white tag on top. As it walked unsteadily his way, gloved hands extended, Paul stepped back and plumbed his embryonic vocabulary for comment: “Don’t like that Kiss.”

Chocolate is one thing, young Paul figures, and he loves it in just about any form. Still, he prefers not to be mauled by ambulatory candy.

I had taken along Paul and his six-year-old brother, Louis, to Hershey, Pennsylvania, as expert witnesses. If Mexico was where chocolate was first treasured, this was where the world’s richest, most can-do nation had taken it after four millennia of evolution. Since I think Hershey’s chocolate tastes like sugared wax, the end result of monster mass production with all corners cut, I recused myself from pronouncing on the most popular chocolate in America. Their parents—my sensible nephew Henry and his sensible wife, Beth—came along as friends of the court.

After two days of gorging on milk chocolate and attempting to digest it while lurching around on Hersheypark roller coasters, we thought the verdict seemed clear. Who cared whether chocolate snobs preferred something that suggests the presence of quality cacao nibs elaborated by skillful artisans? After a century of genius branding, Hershey’s was as American as Old Glory. It was not the chocolate itself but rather the whole idea of chocolate that Milton S. Hershey sold to a vast nation.

In the Pennsylvania Dutch farmlands around Harrisburg, the plucky son of a ne’er-do-well Mennonite dreamer still looms in legend and lore. And, I found, tracing the Hershey mystique to its roots in reality and tracking its evolution reveals as much about the United States as it does about chocolate.

Only days after our July 4 visit in 2002, we realized that Paul might have sensed an unwanted goodbye Kiss. Word leaked out that the guardians of Hershey’s legacy were putting his dream on the market.

Born in 1857 on his family’s homestead farm, young Milton Hershey had no taste for scrabbling in the dirt. From his first years, he was torn between a no-frills mother, a frugal minister’s daughter who wore a white prayer cap under a black bonnet, and a Shakespeare loving father who dismissed his dour Swiss Mennonite fellows as sticks-in-the-mud.

Milton apprenticed as a printer and hated it. He went west to Denver to follow his father but found the rough and raucous city in the midst of a post-boom bust. Back east again, he built up a candy business in New York, which collapsed when his father, Henry Hershey, showed up with grandiose ideas. Milton lost money borrowed from his aunt and for a while survived as a manual laborer. In Philadelphia, he opened a sweet shop that did fairly well until his impractical father showed up once again.

The young man returned home to central Pennsylvania and started a caramel factory in Lancaster. While out west, he had learned to make caramels rich and chewy, with a longer shelf life, by adding fresh milk

instead of the wax and tallow that his competitors still used. But he needed capital. One day, a visiting Englishman placed a huge order to sell in London. Hershey went to the bank. He borrowed seven hundred dollars over ninety days, but when the due date arrived he could not repay it. Instead, he asked for another thousand dollars. It was then that an English banker named Frank Brenneman changed the course of American confectionery history.

Brenneman followed his instinct and paid a call on Hershey’s plant. He was so impressed that he put the loan in his own name, knowing the bank would otherwise refuse it. Barely a week before the money had to be repaid, the Englishman paid his bill in full. Hershey’s Lancaster Caramel Company was launched. It expanded to four plants and a retail store in New York. At thirty-three, its barely schooled proprietor was rolling in money, touring Europe for months at a time and returning with enough art treasures to fill his grand new house.

At the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, a sort of world’s fair, Hershey came upon the booth of J. M. Lehmann, who built chocolate-making equipment in Dresden. He smelled the roasting cacao beans and watched as Lehmann hulled and ground nibs into the heady syrup known as chocolate liquor. Lehmann added sugar, vanilla, and more cocoa butter to form a velvety mass he poured into molds. Milton Hershey tasted his first chocolate bar.

Hershey bought Lehmann’s entire display and shipped it to Lancaster. Hershey Chocolate Company set up shop in a corner of the main caramel factory. Official company history has it that the intrepid founder proclaimed at the outset something like “Caramels are a fad; chocolate is forever,” and plunged into his new métier. There is more to it than that.

In 1898, a decade after the caramel factory took off and five years after his chocolate epiphany, Hershey married Catharine Sweeney, his beloved Kitty. He went on a long break from candy. Kitty, an Irish Catholic beauty with lush dark curls and a sparkling smile, loved to entertain. Even more, she loved to travel. Together, they toured Europe, South America, and the Orient.

Joel Glenn Brenner, in The Emperors of Chocolate, digs deeply into why Hershey set his next course. True, she acknowledges, chocolate was hardly known in America, and it offered the master innovator-creator a blank canvas. Milton Hershey knew it would be wildly popular. But at the same time, he was caught between his feuding mother and father. To ease the growing tension, he decided to sell his candy business and take his wife far away from Lancaster.

Hershey sold the company for a million dollars in 1900 at a time when $950 was a decent annual wage. He sailed off with Kitty for what was planned as a lifelong cruise around the world. Before long, he turned back.

“It wasn’t chocolate that beckoned him to return, however,” Brenner writes. “It was the voice of Henry Hershey still rumbling about in Milton’s head—the voice of a dreamer who had seduced Milton, the child, with fantastical visions of Eden.”

That million dollars could bankroll any dream. “But,” she concludes, “he wasn’t about to reinvest that money in business; his vision was an industrial utopia, a real-life Chocolate Town, where anyone who wanted a job could have one, where children would grow up in celery-crisp air, where mortgages would dwindle in perpetual prosperity. Clear water and clear consciences. This was Hershey’s vision of home sweet home.”

People born long after Hershey died in 1945 are raised on the old stories. Soon after leaving Pennsylvania, I ran into Miriam Weaver, who wore her Mennonite lace cap amid the elaborate hairdos at the New York Fancy Food Show. With her husband, Paul, she runs a nut company in Ephrata, which is part of Hershey’s magic kingdom in Derry Township.

“He is very much loved,” Miriam said. “He really built the town.” Paul nodded vigorous assent. His own great-grandmother was a Hershey cousin. “He gave a lot to the community,” Paul said. “He always thought about people. Have you seen the hotel restaurant? He designed it so that no one would have to sit in the corner.”

Hotel Hershey was inspired by the Mediterranean palaces that Milton and Kitty frequented on their grand tours abroad. When most of America scaled back in fear during the Great Depression, Hershey blasted forward with new projects to buoy spirits. He imported Italian stonemasons and hired an army of local workers. His architect studied a postcard Hershey gave him. The result is fine Americana: a Euro-peanesque hodgepodge of Italy, Spain, and Greece.

Manicured gardens frame a splendid reflecting pool. The spa offers baths in—what else?—foaming chocolate milk. In the Iberian Bar, by a walk-in fireplace under high ornate ceilings, guests can light up cigars in chairs where Hershey chain-smoked his Cuban Corona-Coronas. In the kitchen, Rory Reno, the self-taught chef, tries to blend old-world cuisine with the local spirit. One specialty, which I neglected to try, is foie gras au chocolat.

The hotel’s crowning touch is its dining room, a grand circular hall with towering windows and glass walls all around. Hershey liked to look outside while he ate, the story goes, and he had the room designed so that everyone in the house could share his pleasure.

This was Hershey’s way. True enough, he saw greater profit in a satisfied workforce. But the town seemed happy enough with his largesse. He provided free medical care, subsidized electricity, water, trolley service, a theater, a dance hall, a swimming pool, a junior college, and a hockey arena. He ran the town’s department store, the pharmacy, and—a mixed blessing—the newspaper. He built homes for executives and workers, each different in design to avoid the look of a company town.

At the heart of it, Hershey Park was a great swath of green, with an outdoor bandstand where employees’ families and townsfolk spent summer evenings enjoying pleasures at the limits of Mennonite license.

Kitty died in 1915, only forty-two at the time, and Hershey spent thirty years mourning her. He gave his mansion to the freshly formed Hershey Country Club, keeping only two upstairs rooms where he sat for hours at a time smoking Corona-Coronas and playing chess with an old friend.

The old chocolate factory itself is something to see. Structural steel

and metal siding make up the working part, but the front end, facing the town, was built of cut limestone block that gives the place an air of old Jerusalem. Two smokestacks rise high above the row of cacao silos, proclaiming a prosperity that is visible for miles.

Of all of his projects, the school Hershey founded for troubled orpans was his real love. Kitty had come up with the idea. The couple deeded 485 acres of farmland, together with their homestead, outbuildings, and livestock, as the nucleus of what was to be a model institution for scores of underprivileged boys.

Three years after Kitty’s death, Hershey quietly signed over his entire fortune to the Hershey Trust to keep the school going. The gift included not only thousands more acres of land but also his stock in the company, worth more than $60 million. At sixty-one, with two and a half decades left to live, Hershey had given away everything he had. Five years passed before The New York Times got wind of it.

Today the town’s main attraction is Hersheypark, a modern-day version of the old patriarch’s gardens. Hershey had offered boat rides and then a wooden roller coaster, which still holds its place among the metal monsters of a new age. But now, fenced in behind ticket booths, it is something entirely different, reflecting an America that likes its attractions big. Hershey Entertainment and Resorts Company manages the mystique for two million visitors a year.

Towering flumes send delighted kids and terrified parents looping through the air before plummeting into pools of water. On the Roller Soaker, spectators below can blast away with water cannons, dousing people in the open cars above. There are uncounted places to load up on fat and calories. Souvenir shops squeeze the last drop out of the Hershey motif.

At Tudor Square Mercantile Company, a ye olde schlock shoppe by the main gate, I found Erma Morgan running the cash register. She was on the late shift, folding sweatshirts and chatting happily with customers. Erma had spent most of her eighty-seven years within a buggy ride of Hershey but still spoke English with the hammer-edged accent of Pennsylvania Dutch. That is, German.

“I like it here, and I like coming to work,” Erma said, pausing for an indulgent glance when some kid knocked over a tall stack of books. But, she added, she sure missed Mr. Hershey.

“If he came back today, I think he would take a look and leave right away,” she said. “He was a simple man who believed in doing things for people, and they did things for him. He never did any advertising, and he made all the money in the world. Everyone liked him a lot. He never snubbed anyone. That was the whole atmosphere around here. He always came out and talked to the working people. They were his pride and joy.”

Erma also missed the old park, where people strolled and danced and saw their friends. “Well,” she concluded, “maybe it’s not better for us who remember the old park, but maybe it is for the younger ones.”

A short walk away, Beth Kreider scurried about with a walkie-talkie mike pinned to her collar as she found seats for hungry crowds at the Chocolate World restaurant. At seventeen, she was seventy years younger than Erma. Training as a dancer, she said she might travel with a ballet company but was not eager to leave.

“I’m a purebred Hershey girl,” Beth said. “This place is a little bubble. Everyone is so cheery. It’s so clean. You don’t see any litter. Education here is excellent. And people aren’t fat. When I travel and see all these obese people, I wonder what everyone else eats.”

But, she added, “it is really fading fast. Money has a way of changing people’s minds and habits. I think Mr. Hershey would be very disappointed if he came back today and saw what we waste, what we spend so foolishly.”

The park somehow retains some of its organic sense, kept clean by teams of custodians and watched over by roving junior executives in jackets and ties. Lordly oaks grow among walkways that in summer are ablaze in the pinks and purples of petunias spilling out of their hanging pots. Small sections offer impressions of Arizona’s Sonoran Desert or the Everglades. There is a modest and tidy zoo. Atop it all, a monorail skirts the park’s edge, giving visitors a good look at Hershey’s original plant near the corner of Chocolate and Cocoa streets.

Kathy Burrows, a town native who reveled in her job as Hersheypark

public relations manager, hustled between visiting Japanese television crews and rock stars arriving for nighttime concerts. She is often so busy she mutes the ring of her cell phone. But she believes the high-tech hoopla and commercial overlay are no more than a logical evolution of the old dream.

“All these people who say Milton Hershey would turn over in his grave if he saw this, I mean, gimme a break,” she told me. “How do they know?”

That July, just after I visited, Hershey was likely doing backflips in his grave. His legal heirs, the trustees of his dream to use the profits of chocolate for social good, set about trying to unload the company. They controlled enough shares to do it. In “the sweetest town on earth,” here was irony most bitter. It seemed as if those underprivileged kids—via the corporate board that was acting on their behalf—were running Milton Hershey out of the paradise he built for them.

The old man’s magic had long since passed into the hands of Hershey Foods, a public company listed on the New York Stock Exchange. But in 2002 the Milton Hershey Foundation, which succeeded the old Hershey Trust, still had more than half of its holdings in Hershey Foods and controlled 77 percent of voting shares. For the foundation directors, selling in order to diversify was the next logical step in an inevitable evolution.

After Hershey’s death in 1945, a series of corporate leaders clung to his old ways in the face of fierce new competition. They refused to advertise or even use modern marketing techniques to hold on to their markets.

Hershey’s management could only grit their collective teeth at a popular jingle that Americans seemed to love: “The sweetest things on earth come from Mars.”

The slogan was well chosen. Even today, when most people hear the name of America’s other great chocolate empire, they think of a planet, not a family. The company built by Forrest Mars, Sr., and

passed on to his sons and daughter, was the philosophical antithesis of Hershey’s. Over decades, a single-minded sales force had muscled aside the old favorite in markets across the country. Mars was number one. But change came in the 1960s, when Hershey’s hired away two senior executives, William Suhring, the head of marketing, and Larry Johns, head of sales.

In The Emperors of Chocolate, Brenner put it this way: “Together they introduced the aging, stately Hershey Chocolate Corp. to the cutthroat world of candy that Forrest Mars had created, where Willy Wonka is motivated by greed, rivalry, secrecy and paranoia and will do anything to get you to eat just one more of his chocolate bars.”

As time went on, Hershey and Mars settled into a standoff that occasionally veered into mere gentlemanly competition. Mars, Inc., observed a stony silence on Brenner’s reflections. With no stockholders to demand explanations, there was no need for comment. But later, a senior Mars executive told me with a merry laugh: “Let’s just say reaction was mixed. A lot of what Brenner said was true. And some of it was exaggerated.”

The Forbes roll of billionaires for 2003 listed Forrest Jr. and John, together with their sister, Jacqueline Badger Mars, as tied in the fifteenth place. Each was worth $14 5 billion, an increase of $5

5 billion, an increase of $5 5 billion over 2002. But all three have retired. The company is often known by its larger umbrella, MasterFoods. But those who run Mars still seem to enjoy the shroud of mystery.

5 billion over 2002. But all three have retired. The company is often known by its larger umbrella, MasterFoods. But those who run Mars still seem to enjoy the shroud of mystery.

5 billion, an increase of $5

5 billion, an increase of $5 5 billion over 2002. But all three have retired. The company is often known by its larger umbrella, MasterFoods. But those who run Mars still seem to enjoy the shroud of mystery.

5 billion over 2002. But all three have retired. The company is often known by its larger umbrella, MasterFoods. But those who run Mars still seem to enjoy the shroud of mystery.Marlene Machuti, the company spokesperson, is amused when people note that the McLean, Virginia, headquarters is just down the road from U.S. Central Intelligence Agency headquarters. “Yeah,” she said, “we’re known as the candy equivalent of the CIA. Sure, we don’t give public tours of our plant. But does anybody? Guests are in and out of here all the time.”

Machuti pours passion into Mars’s place in the chocolate galaxy. As a private company, it spends heavily on scientific studies, with laboratories that contribute substantially to the world’s knowledge of chocolate. Its funding also supports rain forest research, which helps planters restore abandoned plantations, fight pests, and grow cacao of better quality.

Mars’s all-chocolate Dove bar, in dark and light, has given Hershey a run for its money since 1992. And, after all, those lovable little M&M’s are still the most popular candy in the world.

Still, MasterFoods lumps its chocolate products in the category of “snack food.” Machuti speaks with equal passion about the Sheba and Whiskas so dear to my cat. Or Uncle Ben’s Rice and the company’s vending machine system. Hershey Foods is also a conglomerate. It is America’s largest pasta maker, and it dabbles in restaurants and products far afield from its original purpose. But, in the end, America’s chocolate icon is Hershey.

By 2002, when the great chocolate tremor shook central Pennsylvania, Hershey had spent thirteen years as the largest candy-maker in the United States. It dominated 48 percent of the American chocolate candy market, with an ever-widening reach overseas. A barely evolved version of the old brown-paper-wrapped bar is still the company’s flagship product. The Kiss, which dates back generations, is a major seller, as are Hershey’s chocolate morsels, its baking chocolate, and those same cans of Hershey’s Syrup that our grandparents used.

If less hermetic than Mars, and forced as a public company to reveal basic financial figures, Hershey Foods also chooses to operate in the shadows. In Milton Hershey’s day, parents drove their kids across America to smell the chocolate up close at the 1,500,000-square-foot main plant. By 1950 annual visitors to the factory numbered in the hundreds of thousands. During the 1970s, Hershey Foods closed its doors. The company said that too many people dropped trash; that crowds traipsing through distracted workers; that traffic congested the town.

annual visitors to the factory numbered in the hundreds of thousands. During the 1970s, Hershey Foods closed its doors. The company said that too many people dropped trash; that crowds traipsing through distracted workers; that traffic congested the town.

annual visitors to the factory numbered in the hundreds of thousands. During the 1970s, Hershey Foods closed its doors. The company said that too many people dropped trash; that crowds traipsing through distracted workers; that traffic congested the town.

annual visitors to the factory numbered in the hundreds of thousands. During the 1970s, Hershey Foods closed its doors. The company said that too many people dropped trash; that crowds traipsing through distracted workers; that traffic congested the town.The unexplained reason was likely more significant: Industrial espionage is a curse of the candy business. Even the lovable Wonka fired all of his workers when competitors mysteriously copied his wondrous products. He had to import Oompa-Loompa pygmies from Africa to keep his secrets safe.

Brenner recalls how a few journalists were allowed inside the Hershey

plant for a product launch in 1993. They watched Hershey’s Hugs roll off the end of the line, but white plastic sheets covered all the machinery used to make them. At the New York Fancy Food Show, I ran into two gentlemen with Hershey Foods name tags and decided to try a shot in the dark. I outlined my purpose, suggesting it might be useful to have a look at the factory innards.

“You can’t,” one of them replied. “But have you been to Chocolate World?” I have to admit that my peal of laughter ranged deeply into the unprofessional.

Chocolate World was my nephew Louis Kay’s favorite part of our trip to Hershey, Pennsylvania. We climbed onto tiny cars for a lurching ride through the chocolate-making process, past a colorful cardboard cacao plantation and into a comic-book version of a chocolate factory. Louis loved the short ride through a roasting oven, where the temperature rose to suggest reality. At the end, the car delivered us to what had to be the world’s biggest candy store, with row upon row of every product Hershey makes and every sort of kitsch doll, mug, and T-shirt that marketing minds could devise.

In fact, that executive was probably right. Chocolate World was a useful insight into the corporate minds of modern-day Hershey Foods and the foundation trustees who minted money from childhood enthusiasms.

Trouble in Hershey went public early in 2002, months before word leaked of the sale. In the first strike in twenty-two years, workers protested cuts in health benefits by a new chief executive, an avowed cost-cutter and the first head of the company ever brought in from the outside. After more than a month, workers went back to their jobs. They kept the health plan but in exchange for other pay concessions.

The strike left a bitter taste, as labor trouble always does in Hershey. Back in 1937, a new union closed the plant with a sit-down strike over matters of seniority. That was during the Depression, when Hershey not only built his grand hotel but also financed the Milton Hershey School buildings and paid off all church mortgages from his

own pocket. Thousands of angry townsfolk marched with signs that read, BE LOYAL TO MR. HERSHEY. HE WAS LOYAL TO YOU.

Hershey’s original gift to the Milton Hershey Trust had grown to be worth more than $5 billion by 2002. The school had 1,200 students, from kindergarten to twelfth grade, no longer only inner-city boys and girls from broken homes. It spent $96,000 per year on each student, and did not suffer for it. The Milton Hershey School had a richer endowment than the University of Pennsylvania, Columbia, or Duke.

Defending their position on the sale of the company, foundation directors said their fiduciary duty required them to diversify holdings. Financial experts, they argued, advise that foundations should hold no more than 5 percent of any one company. Sound advice or not, that line of reasoning brought the town up in arms. In emotional conversations with reporters, people decried the idea of a Cadbury or Wrigley logo looming overhead. For many, everything around them of value traced back to one remarkable man and his chocolate factory. And Milton Hershey was not one to ask directions from his broker.

To most lovers of fine chocolate, Hershey’s is nothing to fight over. Europeans tend to dismiss its taste with evocative words ranging from chalk to cheese. Some call it “barnyard chocolate.” One grand old man of chocolate, Hans Scheu, a Swiss who retired as president of the Cocoa Merchants’ Association of America before he died in 2004, termed it “sour” and “gritty,” without the feel or smell of real chocolate.

Critics can get downright virulent. Émile Cros, a French cacao expert at the world-renowned agricultural center in Montpellier, CIRAD, commutes to Venezuela to help restore original strains of criollo. He is known for his sensitive taste buds. When I asked him for a single word to describe a Hershey bar, he replied, “Vomit.”

Those sound like fighting words. Someone is obviously enjoying

all the Hershey bars and Kisses that after all these years continue to sell in the millions. But this was not about national pride or cultural preference. The deeper I researched, the more I appreciated the pronouncements on inferior chocolate I kept hearing from high practitioners: It is all in what you let yourself learn to appreciate. Wine offers a clear enough illustration.

As a kid, I developed a fondness for Mogen David. After all, I could belt it down at my bar mitzvah, eight years ahead of the Arizona drinking age. It was only later that I picked up those overpowering notes of cough syrup. Now that I have spent some time in Burgundy, it seems plain enough that Morgon, let alone Montrachet, outranks Mogen David. This is not because the former is French. Even middling California wines put to shame most run-of-the-mill European vins de table.

Like it or not, Hershey’s has its own distinctive taste. The beloved founder was no chemist, and he spent little time studying the experiments of others. Unable to learn the closely guarded secrets of the Swiss, he came up with his own trial-and-error formula for milk chocolate, which left a strong note of sour. His conching process, shorter than most, produced a peculiar grainy texture. He was generous with sugar but tightfisted with cacao, and he was not always picky about where he bought his beans.

But Hershey managed to inure a country to his particular style. For most Americans, Hershey is synonymous with chocolate. They still prefer it to anything else, regardless of what many might dismiss as European prejudice. They pour it on ice cream, flavor milk with it, and ingest bits of it by the handful.

The old man built his chocolate empire with care. Pursuing his philosophy—and assuring a reliable source of beans—he ran his own plantations in Cuba and elsewhere in the Americas. The poorest pod cutter was part of his extended family.

In the end, most defenders and detractors agree, one can only expect so much from anyone’s industrial candy. At the mass-market level, things like shelf life, melting point, and that ever-popular watchword economics weigh too heavily in any decision.

Two obvious bidders for the company were among the corporate sharks that schooled around Hershey. Both were giant companies that grew from the backroom beginnings of single-minded men. There was Cadbury Schweppes, the British giant that emerged triumphant from an ugly chocolate rivalry between the Cadburys and the Frys, those two Quaker families in England. And there was Nestle of Switzerland, the largest food company in the world, which was founded by the German pharmacist who invented milk chocolate in Switzerland alongside Daniel Peter.

Following the financial newspapers in the fall of 2002 was like watching the internecine perfidies of daytime soaps.

Hershey’s asking price was reported to be $11.5 billion, which figured in a 10 percent premium over market value. It looked at first as if Nestle and Cadbury Schweppes might jointly buy the company to carve it up. But Cadbury was in a bind. If anyone else bought Hershey, Cadbury stood to lose a $750 million windfall because it was stuck with a fourteen-year-old contract that allowed Hershey—even if its ownership changed—to sell Cadbury’s Almond Joy, Mounds, and Crème Egg products in America.

Nestle had done a similar deal for Hershey to market its KitKat and Rolo brands, but this contract stipulated that rights would revert if Hershey was sold. And that meant the company was worth a billion dollars less to Nestle.

When the story broke, the likely buyers backed off a bit. Beyond the numbers, some European executives were not sure what to make of a little town that got so emotional over a simple commodity and a brand name. During the thick of it, a letter to a friend from Hershey Foundation board member William Alexander found its way into The Patriot-News in Harrisburg.

“The board is not committed to sell,” Alexander wrote.

It is only one of several options being explored. Once and for all we are going to find out if anyone exists who will pay a sufficient premium to justify the sale … My best guess is that the supposed premium

for control will be offset by discounts for the KitKat license and social constraints.

By “social constraints,” Alexander referred not only to angry marches in the streets of Hershey but also to a political storm up the road in Harrisburg. Mike Fisher, the Republican state attorney general who was running for governor, filed a motion to block the sale, at least temporarily. As the defendant was a charitable trust, jurisdiction was under the Orphans’ Court of Pennsylvania.

“We think it’s time the court put a halt to this sale,” Fisher said in a written statement. “We are concerned about the speed in which the Hershey Trust seems to be moving forward with their plans.”

Richard A. Zimmerman, a former chief executive of Hershey, testified for the state. Any buyer would cut spending to make up for the cost of the purchase, he said, adding: “There’s no doubt in my mind there would be some massive changes.”

Foundation lawyers responded that although the trust might be registered in Pennsylvania, Hershey Foods was incorporated in Delaware.

The London Times, meanwhile, calculated the cost that Hershey’s ghost would cast over the deal. Under generous employment conditions, 14,000 employees qualified for severance benefits that could add $400 million to the deal. Benefits were thought to give a broad range of workers up to three times their base salary for two years after a change in ownership.

And then there were passionate people such as F. Frederic “Ric” Fouad, the forty-one-year-old president of the Hershey School Alumni Association. Fouad, born in Chicago to Iraqi parents, visited Baghdad with his father in 1963 when not yet three years old. His father was shot and killed because, the family says, he was openly critical of the Iraqi government. His mother, an American, moved to New York but fell ill. Fouad, often alone, was a terror in public school. At the age of eleven, he ended up in Hershey, and his life turned around.

In interviews with reporters, Fouad left no doubt about how former Hershey kids viewed what he called a shameful scandal. He vowed to block any sale with all the resources he could muster.

In the end, the ghost of Milton S. Hershey prevailed. Buyers balked not only at the inflated price per share but also because of the controversy swirling about the company. Townsfolk kept up the pressure. Lawyers and regulators hovered in the background. Who could calculate the impact of a protracted struggle over an issue of such vague dimensions? Sale-minded directors threw in their cards. Ten members of the humbled foundation board resigned their seats. Another followed later. And fresh directors exerted unusual Hershey chutzpah.

New plans and products were announced. And then one night, New York City looked up to see HERSHEY’S blazing in lights in Times Square above a store devoted to all-American chocolate. A second huge retail store was planned for Chicago.

An energetic but unsuccessful lobby sought to sanctify the name Hershey by, after all these years, having it replace Derry as the township name. Regardless, they had made their point. Yet another Christmas approached with Hershey as America’s synonym for chocolate.

The tumultuous candy war that autumn surprised a lot of people who had never given the subject much thought. For an industry that so heavily traffics in the word sweet, things can get extremely bitter.

As these were matters of food and world-shaping import, the formidable French daily Le Monde wrote a fitting epilogue in 2003, a full page that was headlined HERSHEY: LA VIE EN CHOCOLAT.

The writer, Sylvie Kauffman, noted that the school’s new director was John O’Brien, of the class of 1960, who grew up with neither father nor mother.

She concluded:

On campus, O’Brien, at work on his first day, visits his new domain among the students, busy in their deluxe ghetto, portable computer on his shoulder. Ric Fouad foresees going back to being a lawyer after three years “of a crazy man’s life.” A bus marked “Christian Tours” disgorges visitors in front of the Chocolate Museum …

And everyone in this small world is stocking up with chocolate for the holidays—onty Hershey’s. Michael Weller, alumni director, takes three bars from his drawer; they owe everything to this chocolate. It may not be the best in the world, but who dares to say so? This is still Hershey’s best-kept secret.