CLAUDIO DA PRÍNCIPE

When Claudio Corallo gets his abandoned cacao plantation back in shape—that is, after he reverses the ravages of nature, both human and mother, and accomplishes other assorted miracles in the jungle—he knows what coat of arms to put on the fine chocolate he plans to produce on his West African paradise island. “It will be an enormous cow pie, with flies buzzing around,” he says. “What is more useful for anything that grows?”

A guffaw that punctuates his Florentine-flavored French suggests he is joking. Then again, Corallo is capable of just about anything. The point of his imagined logo is that the quality of chocolate depends not on any sleight of hand at the end stages, and even less on marketing, but rather on healthy trees that produce flavorful beans. He has not been to Hershey, Pennsylvania, but it is a safe bet that he would not like it very much.

Corallo is Crocodile Dundee, Gandhi-style, a slender man with amused eyes and short gray hair. When I met him at the Paris Salon du Chocolat, he was contentedly chewing on a half-smoked piece of soggy brown rope that turned out to be an Antico Toscano cigar. His self-effacing, gentle manner reveals a supreme serenity. Yet he lived for

years growing coffee in the original heart of darkness, deeper in the Congolese jungle than even Conrad would go, facing down enough rebels and reptiles to terrify Tarzan.

When yet another war forced him to resettle, he chose São Tome and Principe, the former Portuguese colony of two lovely islands in the armpit of Africa, just south of Nigeria. That was where African cacao was first planted, and Claudio resolved to restore its former glory.

“This smells like a wet horse, doesn’t it?” he noted, striking a match to his cigar and adding notes of wet horse to the chocolate scents around him. By some miracle of the beatitude he projected, no one seemed to mind. He reached in the pocket of his red sports coat and produced a handful of roasted beans. “When cacao is good, you can eat it raw,” he said. I peeled one and tried it. The crunchy dry texture took some getting used to, but he was right. It delivered an unadulterated hit of chocolaty flavor with an unmistakable hint of fresh olive oil.

Bits of Claudio’s life came at me faster than I could absorb them. He had run a coffee plantation in the Bolivian highlands. He dug into the Tunisian desert doing something brave and strange. As we talked, he showed me a video of his version of the African Queen, built in Italy to link his remote Congo empire to Kinshasa, a thousand miles inland. Like the original, it could slip easily up narrow streams, under tangled growth. But Bogart’s boat could not go from zero to thirty-eight knots in twenty seconds or cruise for twelve hundred miles without refueling.

We spoke in French, but Claudio also has perfect Spanish, Portuguese, and Lingala, the Congolese lingua franca. He never found a need for English.

I learned about Bettina, the beautiful daughter of a patrician Portuguese diplomat in Kinshasa who fell in love with him at fifteen. They married and went off into the jungle a day after her eighteenth birthday. Although Corallo grows coffee on São Tome, he also has twenty thousand cacao trees at a century-old plantation on Principe, the smaller island to the north. He told me about the rich volcanic soils that nourish a superior cacao crop, and the innovative methods of processing the beans. It sounded like a happy counterpart to all of the mediocre cacao produced far away in Ivory Coast.

“You have to come down,” he said finally. I went home and called my travel agent. A month later, he met me at São Tomé’s little shed of an airport.

For a week, I watched Corallo blend science and art with simple humanity in the style of old-world geniuses who shared his Tuscan roots. His homemade fermentation boxes reminded me of the olive presses that Leonardo invented at Vinci. In fact, much of what he did recalled Leonardo. He brought a modern refiner from Spain and then reengineered it to his own demands. He deconstructed formulas no one had questioned for generations. Cow-turd label or not, Claudio da Principe seemed destined to make chocolate to remember.

Claudio left Florence for the Congo in 1974, at the age of twenty three, as an eager young Italian aid worker with a degree in tropical agronomy. Before long, he realized the futility of aid projects that bring in unworkable outside ideas along with easy money that ends up in the wrong pockets. He tried being a coffee broker at one time, but he had no heart for the business. Then he decided to buy a plantation and produce his own coffee. Through force of will and against odds that would discourage any three men, he soon had a backlog of eager buyers in Italy.

A decent plantation is hard enough to establish when you don’t have to sputter along for a thousand miles, dodging crocodiles and malarial mosquitoes, whenever you need to replace a busted widget. But Claudio had it worked out. He and Bettina spent up to two years at a time deep in their jungle, following the world outside with a shortwave radio antenna affixed to an eighteen-foot tower he lashed together in a weekend.

Claudio hunted meat for the table. Bettina learned another twenty ways to make pasta. “It got hard sometimes,” he said. “Once I was in a little cabin fifty miles up a river from the main house and realized all I had to read was One Hundred Years of Solitude.” That flashback brought a reflective cloud of wet-horse cigar smoke.

Bettina, locals said, was the first white woman who had ever lived in the region. For the births of two of their three children, she went to

Buenos Aires, where her father was the Portuguese ambassador. “I wrote her letters and gave them to a guy in a canoe, and they made their way to Kinshasa,” Claudio said. “From there, they went into the post. Three months after I wrote them, they would appear in Argentina. None was ever lost. There is a respect for these things.”

When his workers started to earn wages, he discovered they squandered them at a little settlement nearby, buying useless stuff from unscrupulous traders. So he instituted his own scrip: the soap standard. His monetary unit was a two-hundred-gram cake of Marseille soap, an item everybody understood.

Every day brought some new impossible challenge. When the head of the local riverboat mafia heard Claudio had planned to import his own craft, he tried to cut him off. Claudio finessed that problem with charm and diplomacy. A fanatic about anything that floats, he created so much excitement about his project that even his eventual riverboat competitors couldn’t wait to see his boat in action.

One year, he produced 180,000 tons of coffee, but the world price plummeted. He lost $1.75 million. “If it had been my money, I could have shrugged it off,” he said, “but all of it was borrowed.” Somehow he made good on the loans.

“I took a loan for my boats of nine hundred thousand dollars from the African Development Bank, and I sent them into fits when I wanted to pay it back,” he said. “They didn’t know what to do. No one had ever done that before.”

From the first days after Congolese independence in 1960, the former province of Kasai where Claudio grew coffee was plagued by rebellion and bandits. One day, he politely ran off his land a fearsome brigand known as Pire Kinois, who returned with a heavily armed gang.

“I spent the whole morning with an FAL jammed up my nose,” he said. An FAL is a short, ugly semiautomatic assault rifle. But Claudio kept his cool. At one point, however, he was able to slip away for a moment to go into his house. “I had on shorts, and my legs were trembling so furiously that Bettina thought I was doing a mock jitterbug.”

By lunchtime, he and Pire Kinois were clinking beer glasses together.

Kinois means someone from Kinshasa, but Claudio still doesn’t know if Pire is the local mispronunciation of père, “father,” or if it means what it says in French: “The Worst.”

Two separate times, marauding rebels overran his plantations. They took everything they could carry and left behind smoldering ruins. The first time, Claudio started again from scratch. The second time, he saw no sign that the rebels would melt away as they had in the past. His corner of the Congo seemed destined for endemic strife. He thought about Bettina and their three kids. The oldest, Ricciarda, was barely a teenager; already, she was as darkly beautiful as her mother. It was time to go.

Claudio recounts each of his tales with self-mocking humor, emphasizing his own terror and minimizing the danger he faced. The reality, however, is hard to miss. In early photos, he might be a Cinecitta matinee idol, with bushy chestnut hair, an Errol Flynn mustache, broad shoulders, and a dashing manner. Not that many years later, he is still a handsome man. But his close-cropped hair is steely gray. His features are drawn, and his weight is down after lengthy bouts of river blindness that nearly took his eyesight, dysentery, and several of the deadlier sorts of filarial diseases that decimate African communities. One morning, in a rare somber mood, he shook his head at the end of an anecdote. “You pay a price for this sort of life,” he said.

His coffee plantation in Congo still haunts him. By the time he had to leave, he was boss of twenty-five hundred devoted workers and godfather to another four thousand of their family members. In his absence, the old crew keeps the trees healthy and produces a small crop that does not get to market. He is still owner, on paper, but it is still the tumultuous Congo. Not long before I met him, Claudio had managed to ship desperately needed supplies and a few luxuries to his workers. Rebels stole it all and, for good measure, beat up his foreman.

In those unusual down moments, Claudio allows himself a curse at the vicissitudes of life, but “Madonna!” is about as far as he will

go. That, or “Porca miseria!” He ridicules churches and just about everything else about organized religion. But blasphemy is not in his nature.

When Claudio da Principe met me at the airport in São Tome, he was guffawing happily, with a fresh Antico Toscano billowing a cheery cloud. He loved his cacao trees and was happy that someone had come to visit him. His tiny islands are another universe entirely from the Congo.

If São Tome and Principe have plenty of malaria-bearing mosquitoes, bandits rarely hold guns to people’s heads there. Neighbors might be secretly treacherous but they are friendly. There was a minor revolution in 1995, but it quickly fizzled. When coup leaders tried to gas up the army’s only tankette, irate motorists made them wait in line at the pump like everyone else.

The Corallos live in simple splendor on the São Tome waterside boulevard known as the Marginal. Their house is the one that is almost obscured by gorgeous bougainvillea in deep purple and brilliant crimson. Orchids spill from pots set into the monster-sized twisted stump of a fromager tree. The hedge is a vivid tangle of flowering vines with a name that even Claudio can’t recall. Since he is the Italian honorary consul, a large flagpole looms by the house. But it is always bare, even on Italy’s national day. He has no flag.

Each day, Claudio or Bettina, if not both, drive twenty minutes up a small mountain to Nova Moca, their coffee plantation. It is right next to a plantation called Monte Café, into which the African Development Bank and other donors pumped $14 million. The difference is that Nova Moca thrives while its neighbor is slowly sinking back into the jungle. A stately colonial mansion that was supposed to be a tourist hotel—part of the aid project—is sinking along with it. The $14 million can be found, mostly, in the European real estate of a crafty few.

Depending upon his mood, Monte Café sends Claudio into fits of laughter or bouts of despair. It is dramatic proof that any such tropical

enterprise needs deliberation, commitment, and, above all, a guiding hand.

“It takes years to build a plantation,” he said. “It cannot be forced or pushed too quickly, or there’ll be an imbalance. And without balance, it is disaster. Each step must be taken carefully, with thought toward the next. Above all, you have to think of yourself as immortal.”

Claudio, I saw immediately, was an accomplished agronomist, but his real strength is cultivating people. When an Italian volunteer aid agency sent him to a Bolivian village to work with coffee, he was a rare foreigner addressed as compañero rather than gringo. His Congolese workers stuck by him, no matter what. And in São Tome and Principe, he is family to the people he helps.

At Nova Moca, I got a sense of how he did things. One by one, he visited each worker and listened to anything each had to say. “When they are good at their work, these people are very proud, respected in their communities,” he said. “And without people like that, you’re finished.”

Every few minutes, he unfolded his trusty Opinel knife, retooled to his own specification, for some skillful operation. He pounced on patches of fungus invisible to the unpracticed eye. At a wild cinnamon tree, he stopped to carve us some tasty toothbrushes.

The plantation was jasmine-scented from the trees’ robusta flowers. “The perfume was so strong in the Congo that it gave you a headache,” Claudio said. “We had to close the windows at night.”

We stopped at the collapsing remains of what had been a handsome two-story wood-frame colonial house. It was too termite-ridden to save. Instead, he was converting the barn, with a striking valley view, into the plantation house. “You have to live with your people,” he said.

We stayed a few hours, but I was eager for the following morning. The rattling little plane that made up Air São Tome and Príncipe’s entire fleet would take us to the smaller island, where Claudio grew his cacao.

As we approached the island, Claudio eyed me carefully, and I couldn’t figure out why. Then Principe suddenly appeared. I murmured

something like “Jesus!” and broke into a stupid grin. He burst out laughing. Everyone responds that way to the first glimpse of Principe, and Claudio loves to watch.

“Did you ever see the movie Peter Pan?” he asked. In Florentine French, that is Pee-Ter Pahn.

The whole island is colored in deeply saturated greens, from bright emerald to dark forest tones. Scarlet flowers highlight the tallest trees. Odd-shaped peaks and columns jut high above the jagged mountains. Waves roll over broad swaths of turquoise and lap onto beaches of brilliant white sand. In some places, the mountains drop dramatically to the sea. In others, they slope gently into forests of palms and bananas. I tried to think of someplace more beautiful. Maybe Moorea, possibly not. Even without Tinker Bell, Principe had my vote as paradise.

On São Tome, the little capital is not exactly Lisbon—it has no traffic light, and film must be shipped to Europe for processing—but it is a bustling metropolis compared to the village of Santo Antonio on Príncipe. A small shop sells a few staples. One of the half-dozen churches is an Internet center. The colonial post office has airy verandas and a sloping tin roof. Piles of painstakingly collected junk lay forgotten at the house of a priest who left town. A couple of bars serve the few regulars who can afford a nasty local brew. A louver-sided hospital sits on the hill above the port office.

Two of Claudio’s crew waited for us in his battered Toyota pickup. The windshield was so smashed up you couldn’t see through it, but the sunroof was impeccable. We bounced up a sort of road to Terreiro Velho, the abandoned nineteenth-century plantation into which Claudio was steadily breathing new life.

The view was stunning beyond adjectives. From a low mountaintop perch, the land dropped away to a white sandy cove below, flanked by dramatic rock formations. Those bright red treetop flowers I saw from the air were far more beautiful up close. They were Erythrina, with massive smooth trunks that held towering leafy canopies above the jungle. Fromagers rose high from roots as gnarled as mangroves,

with long pods hanging in eerie decoration. Mangoes, papayas, palms, and a dozen other trees fitted in among them.

This was paradise, all right, and there seemed to be zero chance that any Pire Kinois would disturb the peace. Civilization was always within sight, a far better state of affairs than in the depths of the Congo. But still, in a different sort of way, Claudio da Principe was pushing an even bigger stone up a steeper hill.

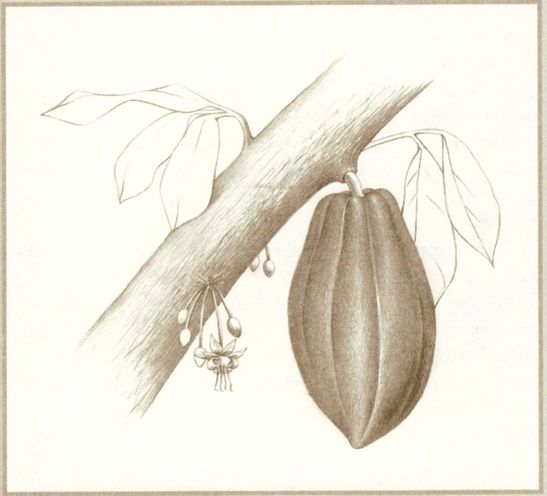

Coffee is not easy to grow, but cacao is a killer. The first trees in Africa were planted in 1822, right next to Terreiro Velho, by Portuguese settlers who brought seedlings from Brazil. The variation, called forasrero amelonado because of its melon-shaped pods, took to Principe. And cacao production relied on what can only be called slave labor.

African workers hacked away chunks of thick jungle to make room for the trees. Then they built elaborate estates of stone and timber for the colonial administrators, along with drying sheds and outbuildings. Plantations were linked by narrow-gauge railways so dried beans could be loaded into wagons and rolled down to port. At Terreiro Velho, rusty tracks still run across the cobblestones by the grand two-story house that Claudio will eventually have time to restore.

In 1900, São Tome and Principe grew 13,900 tons of cacao. The figure rose to 36,500 tons in 1913 and hovered near 30,000 tons after World War I. Then it plummeted when English buyers led by the Cadbury family boycotted the islands because of what amounted to slavery. Figures crept up again. In 1973, just before Portugal granted independence to São Tome and Principe, the output was 12,000 tons.

These days, annual production seldom barely surpasses three thousand tons. Portuguese planters fled along with their national flag. Plantation workers had had enough of slogging away for next to nothing. Unable to attract Western interest in their remote little island nation, the government aligned itself with Moscow. But central planning and state-run farms did not fit the culture. Disenchanted with the Soviet

style, new leaders tried to reorganize cacao production so that small planters could work together to market their crop.

For better or worse, the old-style planters with a firm hand and a single-minded vision are gone for good. Nothing has yet replaced them.

“Here they’ve gone from colonialism to communism to cooperatives,” Claudio said. “These are people with no spark of life in their eyes. We’re not just talking about growing cacao but rather a whole new way to look at life. A cacao farmer needs a certain love for his crop, like a winemaker or an olive grower. That helps in anything, whether you’re a farmer or a shoemaker or tailor.”

Unlike in most former colonies, São Tome and Principe’s trees are still fairly pure versions of the first transplants. By accident of history and geography, the islands were spared an agricultural revolution that stressed high yield at the expense of taste and texture.

“In other places, people saw those immense rugby balls on the new hybrids and looked at yields per hectare, and they tore out their old trees,” Claudio said. “But they forgot that cacao and coffee are plants just like any other. There’s no magic. If I offer you trees that will produce ten or twenty times more, you’ll tell me to get lost before I finish talking. You’d know instinctively that something too important would have to be traded away.”

The future for his islands, he said, was quality rather than quantity. “Volcanic soil composition that you find only on Principe allows you to grow extremely good cacao. It has iron and laterite. We have to find a niche for our cacao, just as if it were wine or olives.” But, he concluded, it would be a hell of a fight.

In the equatorial rain forest, even a single season of neglect can cripple a plantation. Undergrowth breeds fungal diseases and insects that destroy the pods, if not the trees themselves. Without regular pruning, production plummets. Trees grow too high. Tangled vines prevent workers from even approaching the trees, and the overhead canopy blocks out too much light.

“Look at this,” he said, preferring as usual to show rather than tell. He plucked off a pod with a jagged hole on top. “This was a rat,” he

said. “Rats climb down the tree and eat from the top. Monkeys grab a pod and start from the bottom. When undergrowth is dense, you get both.”

Principe is spared witches’-broom and some other virulent pests found elsewhere. But even in optimal conditions, planters calculate they lose 21 percent of their crop to disease and another 25 percent to pests.

Potential nightmares lurk in the back of every planter’s mind. If witches’-broom struck Brazilian trees, might it find its way across an ocean grown narrow in a jet age? What about the monilia that devastated Costa Rica? Or black pod, enemy number one of the cacao world? Botany texts are thick with frightening casts of characters.

Thinking rationally, Claudio started with a small patch of trees by the water. He settled his family into an airy cabin on a dreamlike beach, and they set to work. Soon, local authorities implored him to take on Terreiro Velho, with trees scattered along vertical paths winding up to the plantation headquarters, a half hour’s hike. Being Claudio, he agreed.

“Even before you start worrying about trees, you have to think of the human spirit of a plantation,” Claudio told me. When I marveled aloud at what Terreiro Velho must have been like in the old days, he shuddered. “I could have never stood it then. All those people working so hard with long faces, with no stake in what they did. Just imagine what this place will be like with happy workers who feel like they belong here.”

That human spirit, he added, must extend to distant surroundings. When he first settled on Principe, in the beachside cabin, it took half a day to walk to the town of San Antonio. The actual hike took only an hour. But along the way he stopped to chat with nearly everyone he came across. “You have to take the time,” he said. “If you don’t at first, you’ll have to do it later, and it will be much harder.”

As we drove around the island, it was clear he had done his spadework well.

“Oh, Claudio!” one man in a ragged shirt and spiffy hat yelled as we drove past. Claudio stopped and, after much backslapping, well-wishing, and exchange of gossip, we started up again.

“What did you think of that guy?” he asked.

“Seemed nice enough,” I said, without much to go on.

“Biggest son of a bitch on the island,” he replied, with one of his better guffaws. It seems the man had run one of the three self-help cooperatives Claudio organized for small cacao growers on Principe. The man took advantage of the position, but Claudio managed to bounce him out with such grace that the man bore no grudge.

A few miles down the road, Claudio spotted someone else, and his face beamed warmth. I was hoping he would ask my opinion so I could pronounce the guy a jerk, just for a laugh. At a glance, I could spot real human quality. I could also see biceps and a bulging chest.

Antonio Rochas had a small plot of cacao trees at the bottom of a steep ravine. At harvest time, he humped eighty pounds at a time on his back up to the road. “That’s only because he fell sick and lost a lot of weight,” Claudio said. “You should have seen what he could do when he was in top form.”

One of Claudio’s new projects was to bring a dozen donkeys to haul loads up and down the mountainsides. He had already found a sixty-year-old farmer who spoke perfect donkey to handle them. Trucks made no sense in a place without roads, and not many farmers could hump cacao like Antonio Rochas could.

Rochas was also a fisherman and a local entrepreneur with various irons in the fire. He apologized, saying that illness and other commitments had prevented him from picking up The Boat. As we drove into town, Claudio showed me The Boat, which is one of his “porca miseria” stories.

One day, it seems, a couple of fishermen mentioned they could perform wonders if only they had a decent boat. Plenty of fish schooled around out there. They just had to get to them. Claudio immediately found a boatbuilder in São Tome. From his own pocket, he funded the project. He transported a sturdy yellow craft to San Antonio and deposited it for them on the beach. One year later, the boat sat where he left it, untouched.

Finally, he asked Rochas to take charge of the boat, at least to prevent

it from rotting away out of the water. Eventually, Claudio’s charity would find some purpose. At least he hoped it would.

In San Antonio, no one was yet using the broken industrial refrigerator he had bought to provide the town with a fish smoker. He pours his own money into good works, hiring people to repair the roads in front of their plots of land and funding classes for people eager for education. His gamble is that it will all pay off, with a motivated community committed to doing better. Also, Claudio da Principe, agnostic as he is, is likely to end up sainted.

With all of his friends and endless goodwill to man, his principal focus is still on cacao.

His house has no electricity. Each day starts at 5 a.m. with a freezing outdoor shower. A plastic pipe catches water running down from the mountaintop, except when someone in between needs a drink and whacks it with a machete. At sundown, Claudio straps a high-tech miner’s light to his forehead and sits down to paperwork at his desk: a table with a pocket calculator, a plastic triangle, and a mug of pencils. Then he has his standard Principe meal of sardines or packaged soup.

In its glory days, the century-old house must have been magnificent. Many of the original blue Portuguese tiles have survived in the kitchen. Big breezy bedrooms upstairs had wide windows that looked over the splendor below. The bathroom, with its old monster tub chipped and coated in grime, was a write-off. Neighbors had long since stripped away anything useful, and the empty space left was used to store drums of smelly fuel.

But it was only a minor inconvenience to pad outside to a bathhouse made of woven-mat walls. Cold-water showers are refreshing in the tropics, after the initial shock. Shaving in the open air with a little mirror tacked to a tree has its rustic charm. I got used to the screwy roosters that could not tell time and started their morning racket at 4 a.m. Once ensconced, I would have been happy to rip up my return ticket and stay forever.

The real attraction was Claudio. Night after night, we sat for hours under a blaze of stars talking about life beyond the cacao trees. If Claudio

lives a spartan life on Principe, and a cocoonlike family existence on São Tome, he makes the most of every minute that comes his way.

“People in Europe have enough distractions that they can reach the end of their lives without even realizing that they have never lived,” he said one night. A legion of friends around the world keeps him amused and up to date via e-mail. He doesn’t feel he is missing much. His mother had just sent him a newspaper with a front-page article on Middle East peace talks and Christian-Muslim clashes in Turkey. It was dated December 12, the day she mailed it. But the article was from 1912, ninety years earlier.

While describing his daily struggle to achieve the dream at hand, he spun out previews of coming attractions. He wants to build a catamaran to ply between the two islands. The government runs occasional ferries, but three of them went down in one year. “We can’t be tied to boats that sink with such impressive regularity.”

Claudio never noticed chocolate while he was growing up in Italy. “For some reason, I didn’t eat it as a kid,” he said, “and when I grew up and really tasted it, I thought, merda, I’ve been missing this!” But he is picky about what he eats. A Mars bar he keeps for an emergency energy hit on the nearly bare shelf in his kitchen had gone untouched for months.

On another night, Ricciarda joined us. At sixteen, she already had plans. She wants to study law, perhaps in Portugal or France, and then come home to São Tome and Principe. With her experience over the years, combined with a hard look at international business, she figures she will be well suited to carry on her father’s work.

“I love this place and the life here,” she said. She nodded with enthusiasm as Claudio talked about expanding into chocolate making. “Most people are comfortable with what they already know, so it will take time to change ideas. But it will happen.”

In the meantime, there was Terreiro Velho to put back together. If all goes according to plan, the great house will find new glory, with soul along with electricity. That, of course, would have to wait.

“All of this is tobacco,” he said, waving to a large patch of green-leaved

plants he had cultivated. “If you want a cigar, give me a little bit of warning.” Another guffaw. He had no intention of abandoning his Tuscan smokes. But one cacao pest enjoys a chaw of tobacco, which kills it.

Claudio’s first priority was his drying shed, but first he had to undo decades of abandon. Unearthing the grounds was like rediscovering Angkor Wat. He and his kids were excited to find a single step emerge from a huge heap of dirt. By the time they finished, they had brought back a splendid double staircase with stone banisters decorated with carved rock sculptures. After tons more dirt were carted away, and encroaching trees uprooted, they found rock foundations massive enough to have anchored a Portuguese fort.

Local records reveal little about the original owners, and Claudio had been too busy to see what he might learn in Lisbon. “I asked some of the old guys around here what they remember,” he said. “All anyone can tell me is there was a woman, probably the wife of the owner or the administrator, and she had a nasty temper and a mustache.”

Finally, we reached the piece de resistance, Claudio da Principe’s fermentation and drying operation. For quality chocolate, these are the crucial first steps. A lot can go wrong further along the line, once beans are bagged and shipped. But the first precursors of flavor develop only days after pods are opened. Once this process starts, a master’s hand is needed at every stage.

The shed, four thousand square feet, was built to last, covered by a galvanized and corrugated roof on a solid frame of rafters. In every corner, Claudio had made some personalized new variation on an old theme. His method was trial and error, taking nothing on faith, until he neared his idea of perfection.

In Claudio’s view, the key to making good chocolate, far down the line, is a properly fermented bean. He believes that flavors must begin to develop at this first stage, right out of the pod. His nose follows the process carefully, from the early blast of sweet tropical fruit to the

winelike alcoholic whiff. Only when the last subtle scent of acetic acid vanishes are the beans ready to be dried. Claudio ferments for two weeks, nearly twice as long as Léopold Ouegnin in Ivory Coast.

We inspected his latest idea for fermentation boxes. Carefully chosen planks of a hardwood called iroko were joined into large trapezoids, with two partitions inside. Each was designed so paddles could gently stir the mass. The idea was to keep out air and lock in moisture to give each of the beans even exposure to the heat of fermentation. Over time, the mucilage would disappear and leave chocolate-scented purplish beans ready for the drying process. The boxes were vitrified inside for easier cleaning and so that liquid would not permeate the wood.

Holes in the bottom of the boxes channeled juice from the mucilage into containers. Just about everyone else lets the sweet liquid drain away as so much waste. Claudio distills his into a cacao liqueur that blows your socks off but makes you smile with pleasure.

If all this took a lot of work, I could see distinct advantages over the more rustic method of wrapping the sticky contents of cacao pods in banana leaves and letting nature take its course.

“That might work for the first forty-eight hours,” Claudio explained, “but you have the problem of thermal inertia. You have to aerate the cacao so the heat moves. That’s why we take such trouble to keep beans from getting caught in the corners. The main thing is that with the sun alone, there is no consistency, no homogeneity. You can’t direct it or control it.”

After fermentation, Claudio designed several options. He built two vast expanses of flat clay tiles that serve as drying platforms. A fire of hot coals underneath is kept in carefully sealed compartments to prevent smoke from tainting the flavor of drying beans. Workers carefully shape the beans into long rows, using rake-like hoes, to ensure even temperatures.

But he also crafted his hot tub. This is a great round cylinder in which paddles gently tumble the beans as they dry over forced air.

Both of these processes achieve the same purpose as spreading beans out on a hard surface in the sun. In fact, cacao researchers at Montpellier, France, insist that well-managed sun-drying is best because

of the chemical and physical ways that moisture exits the beans. But Claudio’s method avoids the problems of freak precipitation, old oil stains, incontinent chickens, and the disruption of raking up and covering the cacao at the end of each day.

Claudio is not a great believer in reading manuals.

“I make a thousand different tests to find a cacao that I’d want to eat and have another, and then I go back and figure out what I did,” he said. At every stage, he follows his intuition. When he decides on some new idea, he tries it out three different ways. Then he shapes it to practicality. “What’s important is to keep it simple.”

Early one morning, we took a hike to look at the trees. Claudio was in good spirits, as usual, but just thinking about the work he faced left me nearly paralyzed. Those twenty thousand cacao trees clamored for whatever attention he could spare when he was not worrying about coffee plants on the other island. He had trained thirty workers to do such routine jobs as removing suckers from the base of the trees eight times a year and whacking back encroaching brush. A few skilled hands did the annual hard pruning. It was the proprietor’s job, however, to fret about the future.

I visited at the height of the season, but only a few shriveled pods hung from trunks and branches. Drought had left Principe gasping in thirst two years earlier. The following year, too much rain pounded down just as the flowers appeared. Had Claudio’s trees been healthy and well-pruned, he might still have managed a decent enough crop. But, in the short time he had been at it, his Sisyphean stone was only getting started on its way uphill.

“Ah, look,” Claudio said, brightening as we came to a small copse where workers had gotten a respectable start. “This is going to be okay.” With his trusty folding Opinel knife, retooled to personal standards on a grinding wheel, he cut suckers, taking care to excise them cleanly at the base so the tree would quickly heal. Watching Claudio work, I suddenly began to understand the mysterious and persnickety cacao tree.

A smart planter shapes a young tree to grow from three main boughs that spread from a short trunk. Branches that extend from the

three uprights find their happiest place between light and shade. These are cut back with regular pruning to concentrate the tree’s force on producing healthy pods within easy reach. Branches are thinned and shaped so they do not compete with one another. Despite some formidable differences, I realized, Claudio tended his cacao trees the way he would tend olive trees in the hills of Tuscany.

“It’s agriculture,” Claudio said. “There is nothing mystical about cacao. It needs the right soil, the right growing conditions. It needs pruning and protection from bugs and diseases and parasites. Its roots have to be free to find nutrients. And then it grows.”

That sounded convincing enough. But the whole enterprise also seemed to need a Claudio. The trickiest part of producing cacao is finding the right balances. Young trees, especially, need the shade of a jungle canopy. But they also need light and air. Predator bugs live in the tangled undergrowth that seems to appear overnight. Yet some brush is essential for the midges and other insects that pollinate the cacao.

The tree’s curious botany equips it to produce pods in conditions under which most plants would give up the ghost. Its large deep-green leaves drop off near its base, forming a natural layer of insulation to trap moisture and create the thick rotted mulch that cacao trees love. A profusion of suckers ensures that new branches will grow toward light above, however thick the overhead canopy. The trouble is that the trees were designed for rats and monkeys, not chocolatiers. Misshapen, runty pods are good enough for rodents; all they have to do is distribute seeds.

Pruning is essential not only to shape a tree for easy picking but also to coax it to maximum production. Done well, it reduces competing branches so that more nutrients reach the most promising limbs. Fertilizer and pesticides might help, but both are expensive.

“All the trees around here are organic, although no one can afford to have them certified, because no one can afford the chemicals,” Claudio said. He uses only copper sulfate—acceptable in organic farming—to reduce fungus. In any case, he said, skillful growers learn the best pest control is a healthy plantation with natural deterrents.

“Yes,” he allowed at the end, “I suppose you have to know what you’re doing.”

The need for a healthy environment is one reason Claudio works so hard to encourage and educate his neighbors. Pests have a nasty habit of propagating in overgrown, neglected plantations and then visiting healthier ones nearby at dinnertime. Besides, if São Tome is to produce notable cacao, it cannot be from Terreiro Velho alone. A lot of people have got to be convinced that all their hard work is worth their while.

Tending cacao trees is one thing. The obvious problem is what happens once the pods ripen. In Ivory Coast, small farmers solve this with a machete, some banana leaves, and a patch of highway tarmac. When beans seem to be the right color, they can be shoveled into jute sacks until the local Lebanese traitant sends a pisteur to collect them. But the end result is junk cacao.

Despite their tough-looking exteriors, cacao pods and the beans inside are as delicate as freshly picked olives. If a knife blade damages beans when the pod is cut, spoilage can spread quickly. As the beans dry, they must be kept away from any outside odor. When they are bagged and shipped, they are particularly vulnerable. Surely some cosmic justice allows the occasional whiff of Antico Toscano smoke, but otherwise the cacao gods are strict.

So, I asked Claudio, what do Principe growers do? He raised a finger, inviting patience. The next morning, he said, we would go to a quebra, a day of hard work, with some alcoholic rejoicing, when the crop comes in.

Early, as usual, we hopped into the Toyota and jounced our way to the Porta del Sol, which was built in 1999, one of three cooperative processing centers. It operates permanently during the harvest season, enabling farmers to bring whatever size load they have, whenever it is ready, and exchange it for cash on the spot. Some small producers extract the mucilage and beans at their own plots, saving themselves the effort of hauling husks that will only be tossed aside and burned. But most of them simply deliver sacks of ripe pods.

Quebra means “break.” Instead of slicing open pods with a machete,

endangering the beans inside, workers whack them with a wooden club. After a series of smart blows around the circumference, the pods break cleanly in two. Their contents are scooped out and placed atop a sloping wood plank. As the fresh beans in sticky goo slide down toward a plastic barrel, practiced eyes watch for imperfections. Any off-color bean or bean showing signs of germination is plucked out and dumped.

Afterward, the beans are left to ferment. Then they are spread out on a vast expanse of clay tiles, a larger version of Claudio’s dryers at Terreiro Velho.

Claudio keeps track of every bean. Workers log each delivery, marking them down in the lined columns of a tattered school notebook. At a glance, he can see who produced what and how much was paid. Sitting at his spare table office, he showed me the latest reports. Rochas had hauled in more than a ton. Some less energetic neighbors brought a few pounds. It all counted.

The morning we visited Porta del Sol, Claudio was bummed. We were supposed to see a high-season quebra operating at full bore. These are held regularly, and farmers make a fiesta of it. Each brings in his load of pods or gooey beans, and the whole place rocks with activity. But this was São Tome and Príncipe, where all schedules are only good intentions. The head of the cooperative had to go to the hospital; her youngest son came down with malaria. We saw only a limited version of the quebra, but it was clear enough.

Down a narrow path among fruiting cacao trees, Claudio showed me where he wants to build an overlook café for visitors. The view, as from Terreiro Velho, was breath-stopping. I could imagine busloads of beaming tourists sipping iced cocoa fresh from the source and buying chocolate bars, with Claudio’s coat of arms or not.

The next time I saw Claudio, only months afterward, he was shopping for machinery and studying techniques he could reinvent. Claudio preferred the simplest approach. He experimented with the times and temperatures needed to roast different sorts of beans. But he shortened

the usual long process of conching. If beans were good, he felt, too much manipulation produced chocolate he called cadavere, worked to a cadaverlike lifelessness.

After a few more months, trial and error had turned out some chocolate that he brought to friends in Tuscany. He used no vanilla. The powerful presence of cacao began with the scent alone. A taste revealed notes of tropical fruit with earthy undertones. It was wonderful.

By then, Italian chocolatiers had developed an interest in his singular beans. At a trade fair in Tuscany, he found his photograph displayed prominently in a newspaper over an obvious story: Local boy grows good chocolate.

This was one of those thousand-mile Confucian journeys that began with a single step. By the summer of 2004, Fortnum & Mason offered a line of new chocolate, wonderfully rough and full of rich, earthy flavor. Claudio da Principe had done it.